热门问题

时间线

聊天

视角

無神論

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

Remove ads

無神論(英語:atheism),在廣義上,是指一種不相信神存在的觀念[1][2][3][4][5];在狹義上,無神論是指對相信任何神鬼存在的一種抵制[6][7]。無神論與通常至少相信一種神存在[8][9][10]的有神論相對[8][11][12]。

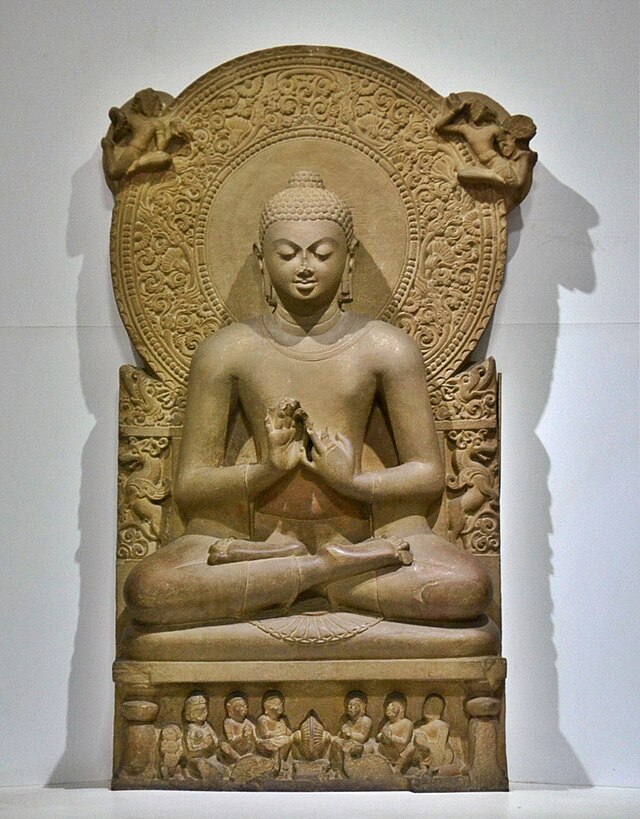

對於神(上帝)和靈魂存在,有著各種各樣截然不同的概念,導致了無神論的適用性的各種觀點。但狹義的無神論否認的事物包括:從神的存在到任何超自然或先驗概念的存在,例如印度教、佛教和道教的觀念。[13]也因此部分學者主張,從哲學觀點來研究所謂堅持無神主義的人或是政治組織,本身亦是持一種如信仰一般的理念存在,並在實務上表現出了類似的行為模式。[14]

簡介

支持無神論的論據包括各類從哲學到社會和歷史的方法。無神論者不相信神存在,因為其缺乏經驗證據的支持[15][16]、無法解釋罪惡問題、各種神的啟示不一致、不可證偽、且沒有考慮無信仰者[15][17]。無神論者認為,無神論比有神論更簡約,而且每個人生來就沒有對神靈的信仰[18];因此,他們認為駁斥神靈存在的舉證責任不在無神論者身上,而是應由有神論者證明有神論正確[19]。雖然一些無神論者採用了世俗主義哲學(例如世俗人文主義)[20][21],無神論者之間並沒有一個共同的思想體系[22]。

20世紀英國的著名哲學家伯特蘭·羅素用其羅素的茶壺的例子說明,任何人都沒有反證斷言的責任,論證有神論者這一立場的錯誤。道金斯進一步用飛天麵條神教和羅素的茶壺作為一個反證法的論述有神論者這一立場的錯誤,如果在無法由科學證明的情況要求相信和不相信一個超自然存在都得到同樣的尊重和重視,那麼它也必須給予相信羅素的茶壺存在同等的尊重,因為茶壺和超自然存在同樣無法去由科學證明或否證[23]。伯特蘭·羅素還在其《為什麼我不是基督徒》一書中,以科學求證的態度否定超自然性和上帝[24]。在一篇成於1952年但從未發表的文章《神存在嗎?》裡,羅素寫到:

我應稱自己為不可知論者;但在實際意義上,我是無神論者。我不認為基督教中的神比奧林匹斯十二主神或瓦爾哈拉更可能存在。用另一個例證:沒有人可以證明,在地球和火星之間沒有一個以橢圓形軌道旋轉的瓷製茶壺,但沒人認為這充分可能在現實中存在。我覺得基督教的上帝一樣不可能。[25]

有「現代物理學之父」之譽的愛因斯坦在其作品《我的世界觀》中是這樣否定上帝: 「我無法想像存在這樣一個上帝,它會對自己的創造物加以賞罰……我不能也不願去想像一個人在肉體死亡以後還會繼續活著。」但事實上,愛因斯坦形容自己為不可知論者,並不同意專業無神論者般的十字軍精神;更仔細解釋,由於人類對於大自然與自己本身的了解可能有缺失,因此應該採取謹慎謙卑的態度。美國猶太領袖拉比赫伯特·高德斯坦曾經問他是否相信神?他回答說:「我相信斯賓諾莎的神,一個通過存在事物的和諧有序體現自己的神,而不是一個關心人類命運和行為的神。」換句話說,愛因斯坦認為,從宇宙世界的存在,可以感覺到神的偉大工作,但神並不會干預人們的日常生活,神是非人格化的神[26]:389-390。愛因斯坦曾經在書信裏表示:「我不相信人格化的神,我從未否認這一點,而且表達得很清楚。如果在我的內心裏有什麼能被稱之為宗教,那就是,對於我們的科學所能夠揭示的世界結構,對於這世界結構的無垠的敬仰。」[27]:43[28]

物理學家霍金在其2010年《大設計》一書中論證宇宙可依照科學原理而渾然天成,不須向上帝過問,甚至沒有所謂造物主的位置[29]。

21世紀初的一群無神論作家所提出新無神論的思想。他們主張「對宗教在政府,教育和政治等任何施加不適當影響的任何地方,它不應該是簡單地被容忍,而應該受反駁、批評,並暴露於理性的爭論之下。」有媒體將丹尼爾·丹尼特、理察·道金斯、山姆·哈里斯及克里斯多福·希欽斯被稱為「新無神論的四騎士」[30]。以前的作家中的許多人認為科學不關心甚至無法處理「神」的概念,理察·道金斯則相反,聲稱「神假說」是有效的科學假說,對物理的宇宙有影響,像其他任何科學假設一樣都可以得到檢驗和證偽。道金斯以其直言不諱的語氣和科學求證的態度挑戰「神創造世界」宗教概念而聞名[23]。他們在2004年至2007年間寫下的一些暢銷書為新無神論的後續討論奠定了理論基礎。隨著時代發展和科學進步的影響,教皇現在希望大眾接受進化論和大爆炸理論[31]。

1979諾貝爾物理學獎獲得者史蒂文·溫伯格警示人們,世界需要從漫長的宗教信仰噩夢中醒來;對我們科學家來說,為削弱宗教信仰而可以做的任何事情都應該去做,實際上這可能是我們對文明的最大貢獻。宗教是弊大於利的[32]。他還認為:無論有沒有宗教,好人都會做好事,壞人都會做惡事;但是,若你想要好人做惡事,就需要宗教了[33]。

由於對無神論的定義各不相同,因此很難準確估計目前無神論者的人數[34]。根據溫—蓋洛普國際在全球範圍內的研究顯示,2012年有13%的受訪者是「堅定的無神論者」[35],2015年有11%是「堅定的無神論者」[36],2017年有9%是「堅定的無神論者」[37]。其他研究人員建議謹慎對待溫—蓋洛普國際的統計數字,因為幾十年來使用相同統計方法且樣本量更大的其他調查得出的數字一直偏低[38]。英國廣播公司2004年進行的一個調查顯示,無神論者為全世界人口的8%[39]。其他較早的估計表明,無神論者占世界人口的2%,而無宗教者占12%[40]。這些民調顯示歐洲和東亞是無神論佔比最高的地區。2015年,中國有61%的人報告稱他們是無神論者[41]。2010年歐洲聯盟的歐洲晴雨表調查數字顯示,20%的歐盟人口聲稱不相信「任何種類的靈魂、神或生命力」的存在,其中法國(40%)和瑞典(34%)占比最高[42]。

跨國研究結果表明教育程度和不相信上帝有正相關性[43][44],事實上無神論在科學家中所占地比例更高這一趨勢在20世紀初就比較明顯,而到20世紀末成為科學家中的多數。美國心理學家詹姆士·柳巴1914年隨機調查1000位美國自然科學家,其中58%「不相信或懷疑神的存在」。同一調查在1996年重複了一次(《自然》雜誌1998年刊登的文章)[45],得出60.7%的類似結果, 而且美國科學院院士中這一比例高達93%。肯定回答不相信神的比例從52%升高至72%。調查顯示美國國家科學院院士之中相信人格神或來世的人數處於歷史低點,相信人格神的只占7%,遠低於美國人口的85%比例。

對無神論的批評也不無存在。例如,批評者認為主張無神論者自身也無法確證神不存在,無神論相信神不存在本身就很接近一種宗教式的信條[46]。美國土耳其裔物理學家、懷疑論者坦納·埃迪斯就認為,沒有證據表明科學離不開無神論。他認為無神論大部分推論都是基於倫理學、或者哲學的推理[47]。啓蒙運動思想家、唯物主義哲學家德尼·狄德羅也對無神論持批評態度。他不認為無神論比形上學更科學[48][49]。

Remove ads

詞源

在早期古希臘語中,形容詞「atheos」(ἄθεος),由否定詞綴ἀ- + θεός「神」構成)的意思是"不敬畏神的"或"邪惡的"。公元前五世紀以後該詞的意思逐漸的演變成了「有意的無神」,成為「與神斷絕關係」或「否認神的存在」而不再是早期的ἀσεβής(asebēs,不虔誠的)。古希臘文的現代翻譯通常會將「atheos」譯作「無神論的」,而ἀθεότης(atheotēs)則譯作抽象名詞「無神論」。西塞羅把atheos這個希臘語詞彙轉寫成拉丁形式atheos。在早期天主教與古希臘宗教的辯論中常常能看見這個詞,雙方都以此輕蔑對方[51]。

在英語中,無神論一詞來自於1587年左右的法語詞彙athéisme[52]。而無神論者一詞(來自法語「athée」,意為「否認或拒絕相信神的存在的人」)[53]在英語中出現的比無神論更早,大約在1571年[54]。無神論者最早在1577年開始被當作不信神者的標籤[55]。相關的詞語則在其後出現:自然神論者,1621年[56],有神論者,1662年[57];有神論,1678年[58];自然神論,1682年[59]。1700年左右,在無神論一詞的影響下,自然神論和有神論的詞義發生了輕微的變化;自然神論的本義與有神論完全相同,但卻有了獨立於有神論的哲學意義[60]。

凱倫·阿姆斯特朗曾記載:「在16到17世紀之間,無神論者一詞仍然只能在辯論中見到……被喚做無神論者是個巨大的侮辱。沒有人願意被稱為無神論者。」[61]無神論在18世紀晚期的歐洲被首次用作自稱,但當時該詞的含義特指不信仰亞伯拉罕諸教[62]。隨著20世紀全球化的趨勢,無神論一詞的意思被擴大到了「不信仰任何宗教」,然而在西方社會,該詞還是主要用以描述「對上帝的不信仰」[63]。

Remove ads

認識論基礎

無神論用形上學[64]的理性分析和科學檢驗的方法,不靠沒有證據的信仰,旨在堅持與其他哲學(如形上學和不可知論)和科學事業相同的理性調查標準,並接受相同的評估和批評方法。這種認識論上的理性的分析方法,也被哲學家和神學家用來研究信仰的本身的合理性,將宗教經典的描述和歷史,考古,和科學發現相比較。

無神論遵循的推理方法類似於自然神論[65]和不可知論,避免了吸引特殊的非自然才能(心靈感應,神秘經歷)或超自然的信息來源(神聖的文本,神學的揭示,信條權威,直接的超自然交流)。這種避免非自然才能或超自然的信息來源的方法,與啟示神學和基督教神學的方法有區別。

無神論的理性分析和科學檢驗的方法與靠信仰的方法相對立。伯特蘭·羅素寫道:基督徒認為自己的信仰行善,但其他信仰卻有害,無論如何,他們對共產主義信仰也是持這種觀點。我堅持的是,所有信仰都是有害的。我們可以將「信仰」定義為對沒有證據的事物的堅定信念,在有證據的地方,沒有人會說「信仰」。我們不說「2加2等於4」是信仰,也不說「地球是圓的」是信仰。我們只在希望用情感代替證據時才談到信仰,用情感代替證據容易導致衝突,這是因為不同的群體用不同的情感來代替。基督徒對信仰耶穌復活,共產黨人相信馬克思的價值論。其中任一種信仰都不能得理性的支撐,因此,每種信仰都只得通過宣傳來維持,必要時還得通過戰爭[66]。

進化生物學家理察·道金斯在其著作〈上帝錯覺〉中批判他所認為的與科學證據直接衝突的所有信仰[67]。他將信仰描述為沒有證據的盲信,一個積極的不思考的過程。他指出,這種做法只會讓任何人僅憑個人思想和可能扭曲的感知(不需要對自然進行檢驗)提出關於自然的斷言(主張); 這種做法,降低了我們對自然世界的理解,沒有任何能力做出可靠且一致的預測,並且無需同行評議[68]。

定義與區分

不同的無神論者信仰不同的超自然實體,不同的無神論對信仰有著不同的界定,考慮到這些問題,人們很難直接的定義與區分無神論[69]。

定義區分無神論時有許多困難,主要因為對如神與上帝等基本概念的定義沒有一致共識,對神定義的多樣性相應的導致了對無神論定義的不同。古羅馬因為基督徒拒絕信奉古羅馬宗教而指責其為無神論者,而在20世紀,無神論一詞則更多的被理解為不信仰任何宗教[63]。

對無神論的定義存有一個問題,那就是一個無神論者對神的「不信」需要到一個什麼程度。無神論的定義有時包括了對有神信仰的簡單缺失。這個寬泛的定義可以把連同新生兒在內的許多從未為接觸過有神論概念的人涵蓋進去。如1772年霍爾巴赫所說:「兒童生來即是無神論者;他們對上帝(是什麼)沒有概念。」[71]同樣地,喬治·H·史密斯在1979年說道:「對有神概念不熟悉的人即為無神論者,因為他不信神。這個分類同樣包含了那些已經有能力去把握,但實際上並沒有清楚意識到神靈概念的兒童們。兒童們對神的不信仰使他們成為了無神論者。」[72]史密斯創造了隱無神論一詞表示「缺乏信仰但並非有意抵制」,同時也創造了顯無神論指代「對自己的不信仰有明確意識」。

在西方文化中,兒童生來即為無神論者的觀點出現的相對較晚。在18世紀以前,西方對上帝存在的信仰是如此廣泛,以至於是否存在真正的無神論者也值得懷疑。這被稱為神學天賦論——一種認為人生來就信仰上帝的觀點;這種觀點簡單地否定了無神論者的存在[73]。還有一種觀點認為無神論者在遇上危難時將很快地投身信仰,例如做出臨終皈依,一句西方諺語「散兵坑裡沒有無神論者」也闡述了這一觀點[74]。這一觀點的部分支持者認為宗教在人類學意義上的益處是宗教信仰能讓人更好的面對逆境(對比卡爾·馬克思在《黑格爾法哲學批判綱要》中提出的精神鴉片說)。一些無神論者則強調實際上有反例,確實存在著「散兵坑裡的無神論者。」[75]

Remove ads

哲學家安東尼·弗魯[76],麥可·馬丁(Michael Martin)[63],以及威廉·L·羅伊(William L. Rowe)[77]等人將無神論分為強(積極)與弱(消極)兩類。強無神論清楚地宣稱神不存在,弱無神論則包含了所有形式的非有神論。根據此分類,所有的非有神論者都必然是強或弱無神論者[78],而絕大多數不可知論者都是弱無神論者。與積極和消極相比,強和弱兩詞用以形容無神論則相對較晚,但至少在1813年[79][80]就已經出現在了各類(雖然用法略有不同)哲學著作[76]與天主教的辯惑[81]之中。

當馬丁等哲學家把不可知論歸類為弱無神論的時候[63],絕大多數的不可知論者並不認為自己是無神論者,在他們看來無神論並不比有神論更加合理[82]。支持或否定神存在的知識的不可獲得性有時被看作無神論必須經歷「信仰飛躍(Leap of Faith)」的標示[83]。一般無神論者對這一論證的反駁包括:未經證實的宗教命題應和其他的未證實命題受到同樣多的懷疑[84],以及神存在與否的不可證明性並不代表兩種可能的概率相等[85]。蘇格蘭哲學家J. J. C.斯馬特甚至說道:「因為一種過於籠統的哲學懷疑論,有時一個真正的無神論者可能會,甚至是強烈地,表達自己為一個不可知論者,這種過分的懷疑論將阻礙我們肯定自己對或許除數學或邏輯定理以外的任何知識的理解。」[86]因此,一些知名的無神論作家如理察·道金斯更傾向於依據「有多大程度相信神存在」的光譜來區分有神論者,不可知論者與無神論者。[87]

Remove ads

如上文所述,積極和消極兩詞與強和弱兩詞在形容無神論時具有相同意義。但是印度哲學家拉奧 (哲學家)在其1972年出版的《積極無神論》一書中給出了此詞語的另一種用法[88]。古拉本人在階級劃分明顯與宗教文化底蘊深厚的印度長大,在他的努力下印度建立起了一個世俗政府,據此他提出了一些積極無神論哲學的指導方針[89],積極無神論者應該具有這樣一些品質:品行正直,對有神論者理解,不強求他人成為無神論者,以及對真理的追求,而不是滿足在爭辯中的勝利。

基本理據

『那是你身體的父親,而那,是你靈魂的父親。』

男孩回答道:

『在我之上的是什麼與我無關,而我為我是這樣一個老人的孩子而感到羞愧!』

『噢,這是何等不敬啊,不願承認你的父親,也不願承認神才是你的創造者!』」[90] 此寓意畫闡明了實用無神論和其在歷史上與不道德的關聯,該寓言原標題為「極端的不敬:無神論和騙子」,取自1552年由巴泰勒米·阿諾所作的《空想詩集》。

信仰無神論的哲學理據在大體上可劃分為實用主義和理論主義兩類,而各種不同理論的無神論又分別來自獨一的論據與哲學論證。與此相反,實用無神論不需要論證,因為其核心概念是對有神論概念的漠視和無知。

在實用,或稱實用主義無神論體系中(又稱遠神論),個人的生活不受神靈的影響,對日常現象的解釋也不用藉助神學。但神的存在並未遭到直接否認,而僅僅被認為無需考慮;在這種觀點下,神既不為個人生活提供目標,也不影響個人的日常生活[91]。對科學界造成影響的一種實用無神論叫做方法論自然主義—即「無論是否全然接收與認可,對科學方法內的哲學自然主義的接納和假設。」[92]

實用無神論有多種表現形式:

- 缺乏宗教積極性—對神的信仰並未推動其道德行為,宗教行為及任何形式的行為;

- 用思想和實際行動主動排斥與神與宗教有關的問題;

- 冷漠—對有關神和宗教的議題缺乏關心;

- 對神的概念不了解[93]。

理論主義無神論要求清晰的提出神不存在的證明,以回應諸如目的論論證與帕斯卡的賭注一類神存在的論證。否認神存在的論據有很多種,通常是以本體論,認識論以及知識論的形式表現,但有時也會表現在心理學與社會學的形式上。

知識論無神論認為人不可能感知到神祇或其存在,其理論基礎為不同形式的不可知論。在內在理論體系中,神與世界是緊密相連的,因此也存在於人的思想中,與此同時,每個人的意識又都必然是主觀的;根據這種不可知論,人類認知所存在的種種限制使得來自宗教信仰的任何客觀推理都無法得出神存在的結論。康德的理性主義不可知論和啟蒙運動只接受人類理性推導得出的知識;這一類無神論認為神不像原則問題般清晰可辨,因而不能確知其是否存在。基於休謨理念的懷疑主義斷言確知任何事物都是不可能的,因而人永遠不能知道神是否存在。對無神論和不可知論的分類飽受爭議;兩者能被看成是不同且相對獨立的世界觀[91]。

其他的能被分類成知識論或本體論的?無神論論證,包括邏輯實證主義和漠視主義,都論述了例如「神」和「神是全能的」一類概念和陳述的無意義性及不清晰性。神學非認知主義認為「神存在」這一類陳述並未表達任何主張,實際上是荒謬無意義的。神學非認知主義應該被分類為無神論還是不可知論一直存有爭議。哲學家艾爾弗雷德·朱爾斯·艾耶爾和西奧多·麥可·德蘭格反對這兩種分類,他們認為這兩種理論都接受「神存在」是一種主張;因而堅持神學非認知主義的獨立性[94][95]。

形上學無神論是建立在形上學一元論——一種認為世界是同質且不可分的概念——的基礎上的。絕對形上學無神論者相信多種不同形式的物理主義,並據此否認非物理的存在。相對形上學無神論者對神的概念則持有較為緩和的否定態度,這種否定態度來源於他們的哲學信仰與神的超然存在或人格等屬性之間的矛盾。相對形上學無神論包括了泛神論,超泛神論以及自然神論[96]。

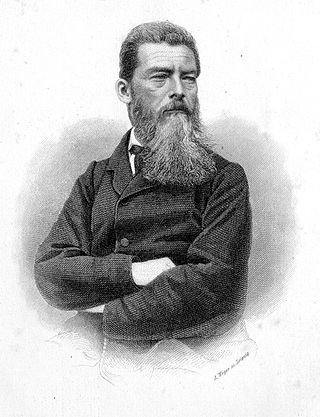

哲學家如路德維希·費爾巴哈[98]與西格蒙德·弗洛伊德認為上帝和其他宗教信仰都是人類自身的創造,其目的是填補許多心理與情感上的需求。這也是許多佛教徒的觀點[99]。受費爾巴哈的影響,卡爾·馬克思和弗里德里希·恩格斯研究神與宗教的社會功能並作出結論,認為它們是統治階級用來壓迫勞動階級的工具。米哈伊爾·巴枯寧則說:「神的概念暗指了人類理性和公義的缺失;它是對人類自由的極端否定,不論在理論上還是在實際中,它都必隨著人類奴役的結束而消亡。」他將伏爾泰的名言「如果上帝不存在,那就必須創造祂。」修改成「如果上帝存在,那就必須拋棄祂。」[100]

基於邏輯學的無神論認為對神的概念的各種不同定義——例如基督教的人格神——都在邏輯上有自相矛盾的本質。這一類無神論者提出了各種演繹論證來否定神的存在,此類論證明確了神的幾種屬性,例如:完美、創造者地位、不朽、全知、全在、全能、全善、超然存在、人之特質、非物質性、正義以及仁慈等[101],是無法和諧並存的。

神義論無神論者認為神學家加給神的各種性質不能與現實的世界調和。他們認為全知,全能和全善的神並不能解釋一個存在著罪惡痛苦以及神性隱退的世界[102]。佛教的創始人釋迦牟尼也曾提出過類似的論證[103]。

價值論無神論,或稱建設性無神論,因為諸如人性等「較高絕對」的存在而否定神。這種無神論論證認為人性才是道德觀和價值觀的絕對根源,人性也能讓人無須求助於神即可解決倫理道德問題。馬克思、弗洛伊德和薩特都曾使用過這種論證去傳達解放、超人說以及無限制的幸福的要旨[91]。

布萊茲·帕斯卡在1669年相對於人本主義論據提出了一個至今仍然很常用的對無神論的批評[104]——那就是否認神的存在將會導致道德相對主義,使人不再有道德的基礎[105],也讓生命變得痛苦和無意義[106]。

信仰無神論的其他論據還包括:

- 無信仰論據:如果全能的神希望自己被所有人相信和讚美,祂們可以證明自己的存在並使所有人都相信。由於有不相信神的人存在,因此或者神不存在,或者祂們對人類不產生影響。不論哪種情況,人們都不需要相信這樣的神。

- 神不存在的超越性證明:針對神存在的超越性證明,後者認為邏輯、科學和倫理都只能在有神論世界觀中才能被肯定,而前者則認為邏輯、科學和倫理都只能在無神論世界觀中才能被肯定。

- 任何文化中都有自己的神話和神。聲稱某一文化中的神(如耶和華)是特殊的並高於其他文化中的神(如女媧)是不合邏輯的。如果一個文化中的神被認為是神話,則所有文化中的神都應該被認為是神話。

- 神的存在源自古人類對大自然愚昧及無知的想像,例如以鬼神之說解釋自然現像如日蝕、風暴,不足為信。霍金在「論神是否存在」的課題例舉古維京人的各種原始信仰[107]。

歷史

儘管無神論一詞出現在16世紀的法國[52],但早在吠陀文化時期和古典時期就已經有無神論概念的記載了。

無神論一詞源起於公元前5世紀的古希臘語ἄθεος,最初指的是對較廣為接受的神靈所持有的否定態度的人[51],被神靈拋棄的人,或未承諾相信神靈的人[108]。這個由正統宗教徒所創造的詞實際指代了一類社會類別,那些與他們的宗教信仰不同的人都會被歸入這個類別[108]。今日語境下的無神論一詞可追溯至16世紀[109]。隨著自由思想和科學懷疑論的傳播,以及對宗教的批評的增多,這一詞語的對象範圍也逐漸狹窄起來。第一個自稱為「無神論者」的人出現在18世紀啟蒙時代[110]。法國大革命是歷史上的第一次與無神論有關的大型政治運動,其倡導人們理性至上[111]。

道家思想成形於先秦時期,直到東漢末「黃老」一詞才與神仙崇拜這樣的概念結合起來。部分學者認為,就本身來說,這種神仙崇拜和道家思想少有相關聯成份,老子、莊子都是以相當平靜的心態來對待死亡的。道家思想是哲學學派,很大程度上是無神論的[112],道教是有神論宗教信仰。引起兩者相關聯的原因可能是在道家的文字描述了對於領悟了「道」並體現「道」的人物意象,道教尊老子為祖師,又追求耳目不衰、長生不死,這和老子的哲學思想是有相悖之處的,將兩者完全混為一談是認識上的誤區。

持道家思想的王充是中國東漢末年的思想家和文學家,他的作品《論衡》在中國思想史上具有重要地位。王充的思想被認為是無神論的[113]。他批評漢末流行的神仙崇拜、批判當時流行的天人感應,[114][115],認為元氣是構成天地萬物最原始的物質基礎。他認為天並不具備情感和意義,它是一個沒有主觀意願的自然實體。同時,他也認為自然現象不是上天的譴責、精神不能離開形體而獨立存在[116]。哲學家馮友蘭認為,王充的觀點在一定程度上否定了當時流行的神秘主義和迷信觀念,強調了理性思維和對自然現象的客觀認識 [117]。

南北朝時期的思想家范縝對統治階級迷信佛教、貽誤國家的行為感到憤慨。他著作《神滅論》,批判宗教迷信、宣傳無神論的思想。范縝認為相信精神可以脫離形體而單獨存在、除了人類的世界之外還有一個獨立存在的所謂"神的世界"這種觀點是一種迷信、是錯誤的。范縝認為精神只有依附於形體才能存在,沒有形體就沒有精神。他強調形體是精神的載體,精神只是形體的作用而已。因此,人死後就只剩下了屍體,精神不可能獨立存在。范縝指出,除了物質世界的時空之外,根本不存在非物質的、超時空的所謂"神的世界"。范縝在《神滅論》中還分析了迷信的基本手段,指出迷信製造者利用人們對鬼神的信仰,誤以為靈魂可以獨立存在,然後通過虛幻迷信的神話來迷惑人、嚇唬人、欺騙人和引誘人。范縝強調,迷信的流行會導致社會道德敗壞,使人們追求私利而忽視親情和幫助窮人的行為。他認為,施捨應該出於真正救助他人的善意,而不是為了立即得到好報[118][119][120]。

20世紀初俄國革命的確促發了之後的一連串革命潮,中國共產黨將堅持無神論的馬克思主義作為中國革命的理論傳入中國。中國共產黨要求共產黨員必須是徹底的無神論者,不僅要堅持馬克思主義無神論,而且要積極宣傳馬克思主義無神論,普及辯證唯物主義的基本觀點[121]。無神論的馬克思主義是當代中國共產黨的指導思想。《中國紀檢監察報》的文章介紹到,按中國共產黨章程來說,每一個中國共產黨員必須是無神論者;公民有信仰宗教的自由,但是共產黨員不能信仰宗教,不能參加宗教活動。[122]

儘管印度教是有神宗教,但它卻包含無神論宗派。出現在大約公元前6世紀,堅持唯物主義和反神哲學的順世派可能是印度哲學中最接近無神論的一派。這一哲學分支被定義成非正統派,被排除在古印度六大哲學派別之外,但因其是印度教中唯物主義運動的證據而值得注意[123]。

其他含有無神論思想的印度哲學流派包括數論派和行業派。相信有神,但對有人格的造物主概念有所排斥的,還有印度的耆那教與佛教[124]。

西方的無神論源於前蘇格拉底時期的古希臘哲學,但直到啟蒙時代後期才發展成明確的世界觀[125]。公元前五世紀的希臘哲學家迪亞戈拉斯被稱為「第一個無神論者」[126],西塞羅在他的著作《論神性》中也提到過狄雅戈拉斯[127]。克里提亞斯把宗教看成是人類的發明,其目的是恐嚇其他人,好讓他們接受道德規範[128]。原子論者如德謨克利特試圖用純粹的,不藉助精神與神秘事物的唯物主義方式來解釋世界。其他具有無神論思想的前蘇格拉底時期哲學家還包括普羅狄克斯和普羅泰戈拉。公元前三世紀的希臘哲學家西奧多羅斯[127][129]與斯特拉圖[130]同樣不相信神的存在。

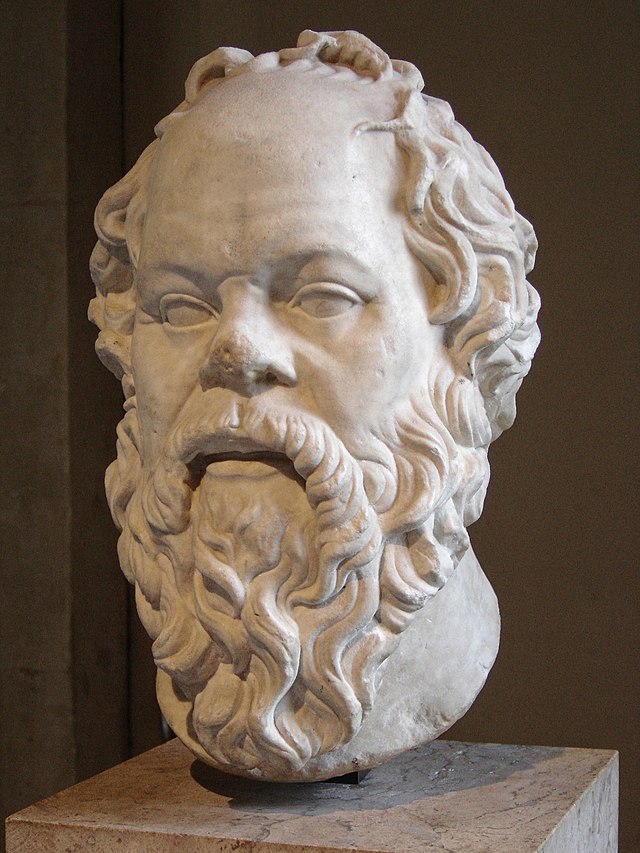

蘇格拉底(約公元前471年–399年)曾因對國家神明(參見尤西弗羅困境)提出質疑而被指控為「不敬」[131]。儘管他以自己相信鬼神為由[132]否認自己是一個「純粹的無神論者」[133],他最終仍被判處死刑。蘇格拉底在與柏拉圖的對話錄《斐德羅》中曾向多位不同的神祈禱[134],還在《理想國》一書中說過「宙斯在上」[135]。

猶希邁羅斯(約公元前330年–260年)認為神來源於受人崇拜的古代征服者,而他們的宗教信仰在本質上其實是對那些早已消失的王國與政體的延續[136]。儘管他並不是一個嚴格意義上的無神論者,猶希邁羅斯仍被批評為「通過在衆人居住的土地上詆毀神祇以傳播無神論」[137]。

原子論唯物主義者伊壁鳩魯(約公元前341年–270年)反對許多的宗教概念,包括來世及位格神的存在;他認為靈魂是純粹物質的與不朽的。雖然伊壁鳩魯主義並沒有明確否認神的存在,但伊壁鳩魯認為,如果神確實存在的話,那祂們對人類是毫不關心的[138]。

古羅馬詩人盧克萊修(約公元前99年–55年)持有與伊壁鳩魯相近的觀點,即若果神存在的話,祂們不會關心人類,也不會影響自然世界。基於這個理由,他認為人類不應懼怕超自然的事物。他在著作《物性論》中闡明了自己對宇宙,自然,靈魂,宗教,道德等等事物的伊壁鳩魯式觀點[139],這本書在古羅馬起到了推行伊壁鳩魯哲學的作用[140]。

古羅馬哲學家塞克斯都·恩披里柯提出了一種源於皮浪主義思想的懷疑觀點,他認為人們不應該對任何一種信仰做出自己的判斷,因為沒有任何事物天性邪惡,而持有這種保留態度的人則能獲得內心的寧靜(Ataraxia)。他遺留的相對大量的著作對後世哲學家帶來了持續的影響[141]。

在古典時期,「無神論者」一詞的意思逐漸的發生著改變,早期的基督徒因為拒絕信奉異教神而被打上無神論者的標籤[142]。到了羅馬帝國時期,大批基督徒因為抵制對羅馬皇帝以及羅馬神祇的崇拜而被處死。而在狄奧多西一世於381年將基督教定為國教之後,基督教的異教又成為了懲罰的對象[143]。

在中世紀前期和中世紀(參見中世紀審判)的歐洲,對無神論思想的擁護是非常少見的;形上學,宗教和神學是當時的主流[144]。但在當時仍然有一些運動在推行與基督教上帝不同的非正統觀念,包括對自然的相異看法,超然存在和上帝的可知性等。一些個人和團體如約翰內斯·司各特·愛留根納、迪南的大衛、貝納的亞馬里克以及自由靈兄弟會(Brethren of the Free Spirit)都持有一種接近泛神論的基督教思想。庫薩的尼古拉則持有一種他稱之為「有知識的無知」的信仰主義觀點,認為上帝超出了人類的理解範疇,我們對上帝的認識都只能依靠推測。奧卡姆的威廉則產生了一種反形上學的傾向,認為人類知識對抽象實體的認識有唯名論的限制,因此神的本質無法被人類理智所直觀和理性的領會。奧卡姆的追隨者,例如米爾庫爾的約翰和奧特庫爾的尼古拉繼續擴展了這種觀點。這些信仰與概念上的分歧影響了此後的一些神學家,包括約翰·威克里夫,揚·胡斯以及馬丁·路德[144]。

文藝復興運動則擴大了自由思想以及懷疑質詢的範疇。一些個人如李奧納多·達文西把實驗看作解釋事物的手段,反對宗教權威的論據。這一時期的其他宗教與教會批評家有尼可羅·馬基亞維利、博納旺蒂爾·德佩里埃和弗朗索瓦·拉伯雷[141]。

文藝復興和宗教改革時期見證了宗教狂熱的再度興起,例如新興教團的擴增,大眾對天主教的忠誠,還有加爾文宗等新教教派的出現。這一時期的宗教間衝突也擴展了當時神學與哲學的討論範圍,為其後出現的懷疑宗教的世界觀奠定了基礎。

對基督教的批評在17與18世紀變得更加頻繁,特別是在英國與法國,根據當時的資料,兩地出現了所謂的「難以名狀的宗教問題」。一些新教思想家,例如托馬斯·霍布斯,支持唯物主義哲學,同時對超自然事物持懷疑態度。荷蘭裔猶太哲學家巴魯赫·斯賓諾莎反對攝理(Divine Providence)概念而支持泛神論自然主義。到了17世紀晚期,自然神論更廣為知識分子所接受,如約翰·托蘭德。不過,雖然自然神論者嘲笑基督教,他們對無神論也持蔑視態度。已知的第一個拋開自然神論衣缽轉而強硬否認神祇存在的無神論者是一位十八世紀早期法國神父讓·梅葉[145]。他的追隨者包括其他更為公開的無神論思想家,例如霍爾巴赫和雅克-安德烈·奈容(Jacques-André Naigeon)[146]。哲學家大衛·休謨基於經驗主義開發了一套持懷疑態度的認識論,破壞了自然神論的形上學基礎。

法國大革命把無神論從沙龍中帶到了公眾面前。強制執行神職人員民事組織法案的嘗試導致了對大量神職人員的驅逐和暴力壓制。革命時期巴黎各種混亂的政治事件最終讓極端的雅各賓派在1793年獲得權力,開始了恐怖統治。在恐怖高潮,一些激進的無神論者試圖用武力強制的將法國去基督教化,把宗教替換為理性崇拜。這些迫害隨著熱月政變而結束,但這一時期的部分世俗化措施對法國政治造成了長久的影響。

拿破崙時期將法國社會的世俗化活動制度化,同時將革命帶到了義大利北部,試圖籍此打造容易受擺布的共和國。19世紀,許多的無神論者和反宗教思想家都投身到政治與社會活動中,促成了1848年革命、義大利統一以及國際社會主義活動的增長。

在19世紀的後半期,無神論在理性主義與自由思想哲學家的影響下變得日益彰顯。這一時期的許多傑出哲學家都否認神的存在,對宗教持批評態度,他們之中有路德維希·費爾巴哈,亞瑟·叔本華,卡爾·馬克思和弗里德里希·尼采[147]。

20世紀的無神論,特別是實用主義無神論,出現在了許多的社會群體中。無神論思想也為更加廣域的哲學派別所認可,它們包括存在主義、客觀主義、世俗人文主義、虛無主義、邏輯實證主義、馬克思主義、女權主義[148]以及普通科學和理性主義。

邏輯實證主義與科學主義為隨後的新實證主義、分析哲學、結構主義以及自然主義鋪平了道路。新實證主義和分析哲學拋棄了古典理性主義與形上學,轉向嚴格的經驗主義與認識論的唯名論。支持者諸如伯特蘭·羅素等斷然地拒絕信仰神。路德維希·維根斯坦在他的早期工作中曾試圖將形上學與超自然的語言從理性論述中分離開來。A.J.艾耶爾斷言宗教陳述具有不可證明性與無意義性,援引了自己對經驗科學的堅定信仰。列維-史特勞斯的應用結構主義否定了宗教語言的玄奧意味,認為它們都源自於人類的潛意識。J. N.芬德利和J. J. C.斯馬特論證稱神的存在在邏輯上是非必然的。自然主義者與唯物主義一元論者如約翰·杜威認為自然世界是萬物的基礎,否認了神與不朽的存在[86][149]。

20世紀同時也見證了無神論在政治上的崛起,尤其是在馬克思與恩格斯理論的推動下。在1917年俄國十月革命之後,宗教自由的增加僅持續了數年,其後的史達林主義轉而壓制宗教。蘇聯和其他社會主義國家在推動國家無神論形成的同時使用暴力手段抵制宗教[150]。

柏林圍牆倒塌之後,反宗教政體的數目大為減少。2006年,皮尤研究中心的蒂莫西·沙(Timothy Shah)博士指出「一股世界性的潮流已經覆蓋各主要宗教團體,那就是相對於世俗運動與意識形態,基於神與信仰的運動的信心和影響力要更為明顯地增長。」[151]前沿基金會的格利高里·斯科特·保羅和菲爾·查克曼(Phil Zuckerman)認為這不盡真實,實際情況較此要複雜與微妙的多[152]。近年來(2000年後)於英美等地興起,攻擊宗教信仰的無神論運動(新無神論)說明了這點,有媒體將丹尼爾·丹尼特、理察·道金斯、山姆·哈里斯及克里斯多福·希欽斯稱作新無神論的四騎士。[153]

國家無神論

國家無神論(英語:State atheism)是一個相對於國家宗教的概念,即由政府所推行的無神論,通常會伴隨著對宗教自由的壓制出現[154]。大部分社會主義國家都有過這樣的政策。

有關「無神論」之不同社會面向

統計無神論者人口很困難,其結果也不準確。原因主要有兩個:第一,世界上一些政府推廣無神論,而另一些政府壓制無神論,因此對於無神論者人口的統計可能過高或過低;其次,由於無神論的定義不確定,許多統計的標準並不統一,其中一些可能僅僅統計強無神論者人口,而另一些則統計無宗教信仰的人口[156]。信仰印度教的無神論者會回答自己是印度教徒,但同時他也是無神論者[157]。無神論概念出自一神信仰的西方,該概念套用到傳統東方文化上可能出現矛盾,如中國人和日本人等東方民族可能介於有神論和無神論間,與西方嚴格區別兩個概念的思維不同。因此統計該地各國無神論者的比例,可能會出現10-90%的極大落差。特別是在日本,大多數人都同時擁有多個宗教信仰(參見日本宗教)。而無宗教信仰者並不同於無神論者,可能近似於不可知論者。

儘管無神論者在大部分國家佔少數,但可以確定的是在共產主義國家(如中華人民共和國、越南、古巴等)和前共產主義國家(如俄羅斯、白俄羅斯等),無神論者人數較多,這是由於共產主義國家曾經強制推行無神論。[來源請求]在西歐、澳大利亞、紐西蘭、加拿大等地區無神論者也較多,之後是美國,世界其他國家地區無神論者較少。[來源請求]根據1995年的調查,無宗教信仰的人口占世界總人口的14.7%,而無神論者占3.8%[158]。與此相近的,在2002年由Adherents.com網站進行的調查表明「世俗的、無宗教的、不可知論的、以及無神論的人口」比例是14%[159]。美國中情局2004年的調查表明12.5%的人沒有宗教信仰,其中2.4%是無神論者[160]。根據《大英百科全書》2005年出版的調查結果,無宗教人口占世界總人口的11.9%,無神論者則占2.3%,這個統計並未包括那些信仰無神論宗教的人,例如佛教徒[161]。

2006年11至12月有調查考察美國和5個歐洲國家的無神論人口,在《金融時報》發布的調查結果顯示,美國的無神論人口比例最低,只有4%;而歐洲國家的比例則較高(義大利:7%,西班牙:11%,英國:17%,德國:20%,法國:32%)[162][163]。對於美國無宗教信仰人口(包括無神論、不可知論、自然神論等)的調查結果從0.4%到15%相差較大,大約16.2%的加拿大人無宗教信仰(包括無神論者),而絕大多數墨西哥人是天主教徒(89%)。其中關於歐洲國家的數字與2005年歐盟官方調查的結果相近,根據2005年歐洲統計辦公室Eurostat的統計,18%的歐盟人口不相信有神存在[42]。對於無神論者、不可知論者和其他不相信人格神的人口比例,2007年的調查顯示波蘭、羅馬尼亞、賽普勒斯和其他一些歐洲國家無神論者所占總人口比例的數字為個位數,而在法國、英國和俄羅斯的比例更高一些,分別為40%,33%和32%[164];北歐地區的瑞典(85%)、丹麥(80%)、挪威(72%)和芬蘭(60%)的比例更高。

由於在日本大多數人都同時擁有多個宗教信仰,所以很難統計無神論者的人數,但有數據稱大約65%的日本人是無神論者、不可知論者或不相信神的存在[34]。中華人民共和國的執政黨中國共產黨的黨員原則上必須是無神論者,據估計目前中國大陸有59%的人口無宗教信仰[165],香港則有14%的人有宗教信仰[166]。以色列有約20%猶太人認為自己是「世俗的」,但其中多數人由於家庭或國家的原因仍參加禮拜[167]。據2003年國際宗教自由報告所述,台灣人民大多數有宗教信仰,目前有近14%的人口不信仰任何宗教[168]。

跨國研究結果表明教育程度和不相信上帝有正相關性[43],歐盟的調查顯示輟學和相信上帝有正相關性[42]。無神論在科學家中所占比例更高這一趨勢在20世紀初比較明顯,到20世紀末成為科學家中的多數。美國心理學家詹姆士·柳巴1914年隨機調查1000位美國自然科學家,其中58%「不相信或懷疑神的存在」。同一調查在1996年重複了一次,得出60.7%的類似結果。美國科學院院士中這一比例高達93%。肯定回答不相信神的比例從52%升高至72%[169]。《自然》雜誌1998年刊登的文章指出,調查顯示美國國家科學院院士之中相信人格神或來世的人數處於歷史低點,相信人格神的只占7%,遠低於美國人口的85%比例[45]。《芝加哥大學紀事報》的文章則指出,76%的醫生相信上帝,比例高於科學家的7%,但仍比一般人口的85%為低[170]。同年,麻省理工學院的弗蘭克·薩洛韋和加利福尼亞大學的麥可·舍默進行研究顯示,高學歷的美國成年人(調查樣本中12%持有博士學位,62%是大學畢業生)之中有64%相信上帝,而宗教信念與教育水平有負相關性[171]。門薩國際出版的雜誌的文章指出,1927年至2002年之間進行的39個研究顯示,對宗教的虔誠和智力有負相關性[172]。這些研究結果與牛津大學教授麥可·阿蓋爾進行的元分析結果近似,他分析了7個研究美國學生對宗教的態度和智力商數的關係。雖然發現負相關性,該分析沒有提出兩者之間存在因果關係,並指出家庭環境、社會階級等因素的影響[173]。

無神論在社會較安定的國家較為盛行,根據心理學家 Nigel Barber,由於當地醫療資源較完善,社會安全網完整,因此未來不確定性較低,無神論者較多。而在較落後的國家中,則鮮少有無神論者。[174]

無神論與宗教信仰

- 堅定地相信超自然性和上帝存在以及有關原則和理論體系

- 以熱情和堅定地信念而堅持信仰的原則和理論體系

《斯坦福哲學百科全書》[176]中無神論條目中定義一章認為,有神論最好被理解為一個命題(或主張),其答案可能是「正確」或「錯誤」。 無神論者不相信上帝不是基於信仰,而是因為他們沒有看到足夠的證據來支持上帝的存在,是基於理性和證據。

山姆·哈里斯等無神論者認為西方宗教對神性權威的依靠使其聯繫上了威權主義與教條主義[177]。而原教旨主義與外誘性信仰(即為獲得利益而信仰宗教[178])則與威權主義、教條主義以及偏見有很深的聯繫[179]。

英國哲學家和邏輯學家諾貝爾文學獎獲得者伯特蘭·羅素反對信仰[66],他認為:「基督徒認為自己的信仰行善,但其他信仰卻有害。無論如何,他們對共產主義信仰也是持這種觀點。我堅持的是,所有信仰都是有害的。我們可以將『信仰』定義為對沒有證據的事物的堅定信念。 在有證據的地方,沒有人會說『信仰』。我們不說『2加2等於4』是信仰,也不說『地球是圓的』是信仰。我們只在希望用情感代替證據時才談到信仰。用情感代替證據容易導致衝突,這是因為不同的群體用不同的情感來代替。基督徒信仰耶穌復活,共產黨人相信馬克思的價值論。其中任一種信仰都不能得理性的支撐,因此,每種信仰都只得通過宣傳來維持,必要時還得通過戰爭。」

關於無神論是否也是基於信仰,宗教和無神論雙方意見不同:

- 一些批評無神論者認為無神論本身也是基於自身的信念而認為神不存在、各宗教的觀點都是錯的,這本身也是一種信仰[46],和各個宗教的信條沒有什麼區別[180]。例如《時代雜誌》的專欄作家伊恩·瓊斯就認為,如果站在一個世俗的角度,那麼無神論者強烈否認神存在的信條似乎和基督新教相信聖經絕對無誤的那些人沒什麼區別[181]。

- 無神論認為他們不是靠信仰,而是沒有看到足夠的證據來支持上帝的存在。無神論一方如伯特蘭·羅素曾用羅素的茶壺認為舉證神存在的責任應在有神論者身上。現代無神論者們進一步用羅素的茶壺和現代反諷性質的飛天麵條神教作為一個反證法的論述,說明如果在無法由科學證明的情況要求相信和不相信一個超自然存在都得到同樣的尊重和重視,那麼它也必須給予相信羅素的茶壺和飛天麵條神的存在同等的尊重,因為茶壺、麵條神和超自然存在同樣無法去由科學證明或否證[23],認為舉證神存在的責任應在有神論者身上。

不過,也有一些無神論者出於傳統文化等因素,依然有一些精神信仰。例如,世俗人文主義下就有猶太無神論或人文猶太教[182][183]以及基督教無神論[184][185][186]和基督徒自然神論。

佛教是否屬於無神論有一定爭論[187][188],甚至許多佛教人士自認為佛教是無神的[189][190]。這是因為佛教的佛與天啓宗教的神有很大區別,可認為是得道的賢人。另一方面,佛教一向是承認鬼神存在的。在《華嚴經》、《地藏經》,乃至於《阿含經》等,都有鬼神記載。佛教認為有天神(天人)、有天帝,而這些神與一般人皆為六道眾生。

倫理道德

關於是否需要靠信神和恐懼以及崇拜上帝才能維持那些與現代社會相容的倫理道德理念. 認為道德必然來自神及不能脫離一個明察善斷的創造主的觀點儘管在哲學上是一個老生常談的論題,但是愛因斯坦認為:

「一個人的道德行為應該有效地建立在同情心、教育、社會聯繫和需求的基礎上;不需要宗教基礎。如果一個人不得不因害怕懲罰和希望死後得到回報而受到限制,那麼他確實是一個可憐的人」

——愛因斯坦, "Religion and Science," New York Times Magazine, 1930

而柏拉圖也用尤西弗羅困境中論證過神在決定事物的正確與否時所扮演的角色不是非必要的就是武斷的,通常被認為是對道德需要宗教這一觀點的最早反駁之一[191][192][193]。

道德戒律如「殺人有罪」一直被看作神聖法,需要一個擁有神性的立法者和法官才能成立。儘管如此,許多無神論者認為像對待法律一樣對待道德本身就包含了一個錯誤類比,道德並不像法律那樣隨著制定者變化[194]。

哲學家蘇珊·尼曼(Susan Neiman)[195]與朱立安·巴吉尼等人[196]認為根據神的要求而表現出道德並不是真正的道德行為,而僅僅是盲目服從。巴吉尼相信無神論是道德的優越基礎,存在一個外在於宗教權威的道德基礎對於評價權威本身的道德很有必要——例如一個沒有宗教信仰的人也能判斷出偷竊是不道德的——因而無神論者在做出這樣的評價時更為有利[197]。

同時期的英國政治哲學家馬丁·科恩(Martin Cohen)給出了許多聖經中的支持酷刑和奴隸的訓諭的例子,作為宗教訓諭是隨著政治和社會發展而不是相反情況的佐證,同時指出了這一趨勢對看似冷靜客觀的哲學發展也是適用的[198]。科恩在其著作《政治哲學:從柏拉圖到毛澤東》(Political Philosophy from Plato to Mao)以《古蘭經》為例詳述了這一觀點,他認為《古蘭經》在歷史上起了一個保護中世紀的社會準則不受時代變化影響的不良作用[199]。

無神論者也可以擁有從認為人類應該一致遵守同一道德準則的人文主義的道德普遍主義到認為道德無意義的道德虛無主義[200]之間任何不同的道德信仰。這一觀點,連同宗教在歷史上造成的破壞,如十字軍東征,異端裁判所以及獵巫與宗教戰爭運動等等,常被反宗教無神論者用以維繫自己的觀點[201]。(參見: 聖經批評#倫理學批評, 對基督教的批評#倫理)

一些生物學和心理學的研究認為,道德倫理是由人類的心理生物學基礎而決定的,而並非是有宗教信仰的人才能具有完整的道德倫理。有人類學的研究認為,道德源於進化,源於人類本身的生物學特性。人類是社會動物,一定程度的克己利人是人類延續的必要條件[202][203]。

英國演化生物學家道金斯認為, 我們不需要宗教就能行善。 我們的道德有達爾文式的解釋:通過進化過程選擇的利他基因賦予人們天然的同理心。他問道:「如果你知道上帝不存在,你會殺人、強姦或搶劫嗎?」 他認為很少有人會回答「是」,這削弱了宗教在道德行為方面的必要性。為了支持這一觀點,他回顧了道德的歷史,認為存在一種道德時代精神,它在社會中不斷演變,總體上向自由主義發展。隨著它的進展,這種道德共識會影響宗教領袖如何解釋他們的神聖著作。因此,道金斯指出,道德並非源於聖經,而是我們的道德進步決定了基督徒接受和否定聖經的哪些部分。[23]

FiveThirtyEight數據記者和作家Mona Chalabi 通過分析美國司法部的美國司法統計局2013年的報告[204],調查美國聯邦囚犯中有宗教信仰的比例,發現監獄囚犯自稱為無神論者的比例為0.1%。她同時又找出2008年美國的人口普查數據,根據2008年人口普查中有1%的無神論者,得出監獄中自認為無神論者的比例相對較低的結論。但是,她自己也在文中指出,囚犯信仰的數據中含有一個「其他」的分類,而她在比較中直接去掉了這一分類。另外,她也指出,監獄中囚犯各信仰比例與總人口中各信仰比例的不同也可能是由族裔、政經地位等因素造成,很難簡單一概而論[205]。 對文章探討的問題 「監獄中無神論者犯人的比例是低於人口中無神論者的比例嗎?」 Mona Chalabi綜合其它問題討論的最後回答是: 無論如何,關於監獄裡的宗教信仰,你是對的: 監獄中無神論者犯人的比例是低於人口中無神論者的比例。

美國作家和無神論活動家Hemant Mehta 根據2021年美國聯邦監獄局 提供的數據[206]指出,2021年無神論者僅占聯邦監獄人口的 0.1%,又指出根據2021年皮尤研究中心的數據[207],自我認定的無神論者占人口的4%。 這可以得到,獄中無神論者犯人的比例是於人口中無神論者的比例40分之一。 另一方面,他指出,這一數字不能說明無神論者比有宗教信仰者更加道德,因為無神論者因為在監獄中可能處於相對的弱勢地位而選擇偽報自己的信仰狀況,也可能是一部分並不相信有神的囚犯並不知道到底什麼才是無神論。此外,這些數據也只覆蓋了聯邦監獄系統的囚犯,而各州監獄(美國)囚犯的數量比聯邦監獄多得多。 但他認為這一數字至少表明假定無神論者都不道德這個觀點站不住腳。文章中指出:

- 「人們認為,如果你有宗教信仰,你永遠不會做出讓自己入獄的可怕事情。他們認為,做這種事的人不是真正的基督徒。但是,當新教徒約占聯邦監獄人口的 23%、天主教徒占 17%、穆斯林占 8.1%(我們現在知道他們確實如此)時,就很難說所有這些人都誇大了他們的信仰。」

- 特別強調 "當在監獄裡找到一名公開不信教的囚犯就像大海撈針(finding a needle in a haystack)一樣時,基督教護教者和牧師就更難辯稱信仰對於讓人們走在正義的道路上是必要的"[208]。

- 最後的結論是,「救贖之路並不經過神。」

關於同樣的數據,另外有一種解讀是,因為監獄囚犯生活相對苦悶,所以也許監獄的囚犯更容易從無神論轉換為信仰宗教者[209]。

基督教神學家大衛·本特利·哈特教授認為基督教與各種宗教及無神論者相同,都有暴力歷史。但如果以20世紀為例,無神論者殺戮記錄更多(該書第12頁)[210]。對其著作Atheist Delusions的評論可見於:[211]

與大衛·本特利·哈特相反的觀點如下:

- 20世紀的希特勒對600萬猶太人被種族滅絕的納粹大屠殺和史達林清洗和屠殺等是分別以納粹和共產主義的信仰為名義,不是以信無神論和不信上帝為名義;歷史上沒有以信無神論名義和不信上帝而發起的戰爭[23]。 許多宗教戰爭的原因也可能還包括國家和民族的利益,但卻是以宗教名義和信仰上帝而發起的,如延續近200年幾十萬十字軍死亡的十字軍東征、包括平民有約800萬人死亡的三十年戰爭[212]、三百萬民眾死於戰亂及引發的饑荒和瘟疫的法國宗教戰爭。20世紀戰爭中的士兵中既有有神論者和也有無神論者,希特勒士兵中有神論者遠多於無神論者,把有神論者和無神論者士兵殺戮都歸於無神論者,來斷言「無神論者殺戮記錄更多」觀點也是錯誤的。[213]

- 理察·道金斯指出,史達林的暴行並非受到無神論的影響,而是受到教條馬克思主義的影響[67]。並得出結論,雖然史達林和毛碰巧是無神論者,但他們並沒有「以無神論的名義」行事[214]。道金斯稱:「重要的不是希特勒和史達林是否是無神論者,而是無神論是否有系統地影響人們做壞事。沒有甚至最小的證據表明它確實如此」。[67]:309-309

1979年諾貝爾物理學獎獲得者史蒂文·溫伯格警示人們,無論有沒有宗教,好人都會做好事,壞人都會做惡事。但是,若你想要好人做惡事,就需要宗教了[33]。比如,施行恐怖行動的宗教信徒人可能是不偷不搶的好人,但他們堅信九一一襲擊事件、炸地鐵等恐怖行動等按其宗教和上帝旨意是正確行動可以上天堂,所以犯下殘忍的暴力恐怖罪行。但沒有任何人能理性地以信無神論和不信上帝的名義,而施行911及炸地鐵等恐怖行動。

參見

參考書籍

- 《上帝錯覺》新無神論代表作之一。 作者理察·道金斯是當代最著名的無神論者之一,牛津大學大眾科學教育講座教授, 英國皇家學會會員。他崇尚科學與理智並批評世界上所有的宗教都是人類製造的騙局。他在書中指出基督教《舊約》中的上帝是一個妒嫉心強、非正義、歧視同性戀、喜好殺人等等使人憎恨的惡霸。道金斯在書中批駁有神論者的各種觀點,並解釋美國的開國元勛們其實十分厭惡基督教。[215]

- 《上帝不偉大:宗教是如何毒害一切的》是一本2007年出版的批判宗教的非虛構類書籍,新無神論代表作之一。作者是由作家兼記者克里斯多福·希欽斯。

- 《The God Argument: The Case against Religion and for Humanism》。

- 《無神論錯覺》基督教神學家大衛·本特利·哈特教授的著作,試圖反駁新無神論。

參考文獻

外部連結

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads