Loading AI tools

武装冲突 来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

俄國內戰(俄語:Гражданская война в России,羅馬化:Grazhdanskaya voyna v Rossii),也稱為蘇聯國內戰爭、蘇俄國內戰爭、第12次俄土戰爭、俄國革命或對蘇干涉戰爭,是於1917年11月—1922年10月,在前俄羅斯共和國境內發生的一場戰爭,交戰雙方是紅軍和由共和國臨時政府力量組成的聯合力量白軍,還有協約國出兵干涉,部分戰事還蔓延到蒙古和波斯。

此條目翻譯品質不佳。 |

| 俄國內戰 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 第一次世界大戰和1917年—1923年革命的一部分 | |||||||||

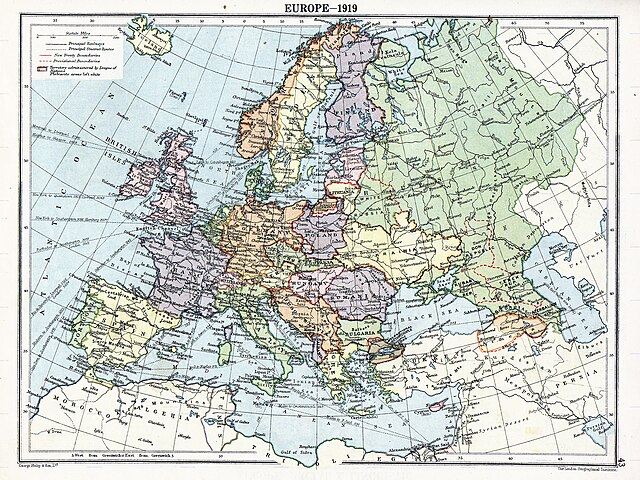

從上起順時針,1919年的頓河軍、1919年的西伯利亞軍、紅軍第一騎兵軍、1918年的托洛茨基、1918年在葉卡捷琳諾斯拉夫被奧匈軍絞死的農民 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| 參戰方 | |||||||||

|

|

包括 新建立國家 協約國武裝干涉 同盟國勢力 | ||||||||

| 指揮官與領導者 | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| 兵力 | |||||||||

|

3,000,000人[3] 烏克蘭革命起義軍103,000人 | 白軍2,400,000人;協約國255,000人 | ||||||||

| 傷亡與損失 | |||||||||

|

1,212,824人死傷 記錄不完整。[3] | 至少1,500,000人死傷 | ||||||||

事件起因是列寧領導的布爾什維克蘇維埃份子向俄羅斯共和國政府發動武裝革命。俄羅斯官方稱法為「1917年—1922年的內戰和俄國大革命」。蘇維埃力量於1919年在烏克蘭擊敗共和國軍南俄武裝力量,並在西伯利亞擊敗亞歷山大·高爾察克的武裝。隨後彼得·弗蘭格爾領導的共和國軍於1920年秋在克里米亞被蘇維埃力量擊敗。

許多獨立運動隨着俄羅斯共和國的崩潰和戰爭的進行而發起。[2]其中芬蘭、愛沙尼亞、拉脫維亞、立陶宛和波蘭成為主權國家。前俄羅斯共和國的其餘領土在戰後成立俄羅斯蘇維埃社會主義聯邦共和國和其他國家一併加入蘇聯。

俄羅斯帝國從1914年起即與法蘭西第三共和國和大不列顛及愛爾蘭聯合王國(三國協約)一起參加了第一次世界大戰,對抗德意志帝國、奧匈帝國和奧斯曼帝國(中央同盟)。

二月革命迫使沙皇尼古拉二世退位,導致新成立的俄國臨時政府與全國各地組織起來的蘇維埃(由工人、士兵和農民組成的民選委員會)形成了雙重政權的局面。1917年9月,俄羅斯共和國宣布成立。

在十月革命發起的時候,舊的俄羅斯帝國軍隊被解散;志願者組成的赤衛隊是布爾什維克主要的軍事力量,由布爾什維克政權的安全機構契卡的武裝軍事部分擴建而來。一月,在戰鬥中遭遇重挫後,戰時人民委員列夫·托洛茨基領導赤衛隊改組為工農紅軍,以創建更專業的武裝力量。政治委員被任命到每個支隊以維持士氣並保持忠誠。

1918年6月,純粹的工人組成的革命軍將會變得弱小的問題凸顯出來,托洛茨基在紅軍中建立了面向鄉村地區農民的強制徵兵制。[4]俄國農村對紅軍徵兵部隊的反抗被劫取人質及為強制執行而實施的槍殺鎮壓,[5]同樣的手法也被白軍軍官完全運用。[6]革命家以「軍事專家」(voenspetsy)的名義啟用前沙皇軍官,[7]有時為使他們保持忠誠而將其家屬劫為人質。[8]戰爭開始之際,四分之三的紅軍軍官由前沙俄時期的軍官組成。[8]戰爭結束時,所有紅軍師級和團級83%的指揮官都是前沙皇時期的將士。[9]

白軍對紅軍的反抗開始於布爾什維克起義隨後的時日,和德國、奧匈帝國、保加利亞、鄂圖曼帝國簽訂的布列斯特-立陶夫斯克條約和政治禁令成為俄國內外反布爾什維克團體建立的導火線,[10]把他們推進反抗新政權的行動中。

反布爾什維克力量組成的鬆散的聯盟公開反對布爾什維克,包括地主、共和主義者、保皇黨人、中產階級公民、反動派、前君主主義者、自由主義者、軍官、懷有不滿的非布爾什維克社會主義者民主改良主義者,只因他們反對布爾什維克統治而自願聯合。他們的武裝力量由強制徵兵和恐懼[6]和外國影響所支撐,並由尤登尼奇將軍、海軍上將高爾察克和鄧尼金將軍領導,人稱白軍,並且在戰爭中的大部分時候控制着前沙皇俄國的重要部分。

被稱作黑衛軍的烏克蘭民族主義運動在戰爭初期活躍於烏克蘭。更重要的是被稱作烏克蘭革命起義軍或由內斯托爾·馬赫諾領導的無政府主義黑軍的無政府主義政治和軍事力量的出現。擁有為數眾多的猶太人和烏克蘭農民的黑軍在1919年阻止鄧尼金將軍的白軍向莫斯科的進攻時發揮了關鍵作用,隨後從克里米亞驅逐了哥薩克武裝。

伏爾加河流域、烏拉爾山區、西伯利亞和遠東地區的遙遠距離受到反布爾什維克力量的青睞,而且白軍在這些地區的城市建立了許多組織。一些軍事力量建立在這些城市中的秘密軍官組織的基礎上。

捷克斯洛伐克軍團曾經是俄軍的一部分,並在1917年10月有30,000人的部隊。他們和新的布爾什維克政府達成了從東方戰線通過海參崴的港口到法國撤退的協議。從東方戰線到海參崴港口的交通在混亂中變得緩慢,而且裝甲兵全部分散在西伯利亞鐵路兩側。在同盟國的壓力下,托洛茨基下令解除武裝並逮捕士兵,這給布爾什維克造成了壓力。

協約國也對布爾什維克表現出了驚訝。他們擔心:(1)俄羅斯與德國可能會聯手(2)布爾什維克的前景會給他們造成不負責任和違約及俄羅斯帝國大量外債的恐懼(3)共產主義革命思想會傳播蔓延(許多同盟國也有此擔憂)。因此,這些國家的大多數都支持白軍,對其提供裝甲和物資。溫斯頓·丘吉爾宣稱布爾什維克主義必須「扼殺在搖籃裡」。[11]英法兩國為俄國支援了大量戰爭物資。條約簽訂後,有跡象表明這些物資很多都落入德國之手。在這一藉口下協約國武裝干涉俄國內戰以英法向俄國港口派遣部隊開始。那裡有效忠布爾什維克的軍隊的暴力衝突。

德國和奧匈帝國發動十一天戰爭入侵蘇維埃俄國後,並在布列斯特-立陶夫斯克條約下創建了幾個短命的衛星緩衝國:「庫爾蘭和瑟米利亞公國」、「立陶宛王國」、「白俄羅斯人民共和國」和「烏克蘭國」。隨着德國於1918年11月在西線中戰敗,這些國家被廢除。

芬蘭王國是於1917年12月率先宣布從俄國獨立的政權,並在隨後於1918年1月至5月發生的芬蘭內戰中覆滅。波蘭第二共和國、立陶宛、拉托維亞和愛沙尼亞在布列斯特-立陶夫斯克條約被廢除後建立了自己的軍隊,並在1918年11月打響蘇聯西線攻勢。

在俄國的歐洲部分,戰爭經歷了三條主要的前線:東部、南部和西北前線。還可大致分成下列階段。

第一階段是從革命一直持續到停火。早在革命那天,哥薩克將軍卡列金拒絕承認並取得頓河流域所有政府軍的指揮權,[12]在那裡開始得到志願軍的支持。布列斯特-立陶夫斯克條約的簽訂也直接導致了盟國的直接干預及對布爾什維克政府的武裝反抗。有許多德國軍官也要求支持反擊布爾什維克,出於與之正在逼近的對抗的擔心。

第二階段,布爾什維克從臨時政府和白軍手中控制了中亞,在草原地區和突厥斯坦建立了共產黨支部,那裡有2百萬俄羅斯人定居。[13]

許多發生在第一階段的戰鬥是零星的,表明只有一小部分人處在易變的環境下並迅速轉移戰略場景。處在對抗地位的是捷克斯洛伐克人,被稱作捷克斯洛伐克軍團或「白色捷克人」;[14]波蘭第五步兵師的波蘭人和支持布爾什維克的紅色拉脫維亞步兵團。

戰爭的第一階段從1919年1月一直持續到11月。起初白軍從南部(鄧尼金將軍指揮下)、東部(高爾察克海軍上將指揮下)和西北部(尤登尼奇將軍指揮下)的進軍取得了成功,迫使紅軍及其左翼盟友撤退到全部三條戰線。1919年7月,紅軍在大批叛軍在克里米亞加入內斯托爾·馬赫諾領導的無政府主義黑軍後遭遇了另一次失敗,使無政府主義武裝在烏克蘭鞏固了權力。

列夫·托洛茨基很快改革了紅軍,終結了兩個無政府主義軍事同盟的第一個。6月,紅軍首先打退了高爾察克的進軍。經過一系列的交戰,在黑軍進攻白軍補給線的幫助下,紅軍分別在10月和11月擊敗了鄧尼金和尤登尼奇的軍隊。

戰爭的第三階段在克里米亞延長了對最後一支白軍的圍攻。弗蘭格爾召集了鄧尼金軍隊的殘餘勢力,占據克里米亞大部分地區。向烏克蘭南部進軍的企圖被內斯托爾·馬赫諾領導的無政府主義黑軍挫敗。被馬赫諾的部隊推進到克里米亞後,弗蘭格爾在克里米亞轉入防禦。北上反擊紅軍失敗後,弗蘭格爾的軍隊被紅軍和黑軍向南推進,弗蘭格爾和殘餘勢力於1920年11月撤退到君士坦丁堡。

十月革命中,布爾什維克黨領導赤衛隊(工人和帝俄軍隊的逃兵組成的武裝)以奪取對彼得格勒(聖彼得堡)的控制,並迅速展開對前俄羅斯帝國城市和鄉村的占領。1918年1月布爾什維克解散了俄國臨時政府並提前宣布蘇維埃(工人的代表會議)為俄國的新政府。

最初從布爾什維克手中奪回政權的嘗試是1917年10月發動的克倫斯基-克拉斯諾夫起義。這次起義受到彼得格勒的容克兵變的支持,但很快被赤衛隊尤其是拉脫維亞步兵分隊鎮壓。

最初反對共產主義者的群體是聲稱忠於臨時政府的哥薩克軍隊。頓河哥薩克的卡列金和西伯利亞哥薩克的謝苗諾夫都是其中的一員。過去沙皇時期的軍官也發起反叛。11月,一戰時期沙皇的參謀長阿列克謝耶夫將軍開始在新切爾卡斯克組織志願軍。這支部隊的志願者好多都是俄國老兵、軍校學員和學生。1917年12月,阿列克謝耶夫接納了科爾尼洛夫、鄧尼金和其他革命前因科爾尼洛夫事件後被捕而關押的地方逃出來的沙俄軍官。[15]1917年12月初,志願軍和哥薩克占領了羅斯托夫。

1917年11月「俄羅斯各族人民權利宣言」宣稱沙皇統治下的各國應給予自主權後,布爾什維克在塔什干建立突厥斯坦委員會後開始在中亞地區奪取臨時政府的權力。[16]1917年4月,臨時政府建立了這個委員會,其中大部分都是前沙皇時期的官員。[17]布爾什維克曾於1917年9月12日試圖控制塔什干的委員會,但行動失敗,而且不少布爾什維克領導人被捕。然而,因為委員會缺乏當地人的支持且定居的俄羅斯人很少,他們不得不因為公眾的強烈抗議迅速釋放了布爾什維克犯人,並且兩個月後的11月這個政權被接管。[18]布爾什維克在1917年推翻臨時政府的成功很大程度上歸功於他們受到了中亞工人階級的支持。1917年3月由1916年為沙俄政府去後方工作的俄羅斯定居者和當地人建立的伊斯蘭勞動人民聯盟於1917年9月在工業中心發起了多起罷工。[19]

然而,在布爾什維克推翻臨時政府後的塔什干,穆斯林精英在突厥斯坦建立了自治政府,通稱「浩罕自治政府」(或簡稱浩罕)。[20]白俄支持了這個政府幾個月,由於布爾什維克軍隊與莫斯科失去了聯繫。[21]

1918年1月蘇俄在穆拉維約夫中校領導下進入烏克蘭中央拉達控制的烏克蘭地區並攻占基輔。在基輔兵工廠起義的幫助下,布爾什維克於1月26日攻占基輔。[22]

作為他們在革命前對俄國人的承諾,布爾什維克決定立刻同德意志帝國和其盟友議和。[23]弗拉基米爾·列寧的政治對手認為那個決定是由德皇威廉二世的外交部資助給予列寧所希望的,包含一場革命、俄國退出一戰。這種懷疑受到德國外交部資助列寧返回彼得格勒的支持。[24]然而,隨着俄國臨時政府發動的夏季攻勢(1917年6月)的慘敗,而且特別是夏季攻勢慘敗後臨時政府打亂了俄軍的編制,列寧實現承諾的和平就變得至關重要。[25][26]甚至在夏季攻勢失敗前俄國人就對戰爭的繼續進行感到懷疑。西方的社會主義者如比利時的埃米爾·王德威爾德從英法迅速地趕到俄國去勸說俄國繼續參戰,但無法改變俄國新的反戰主義情緒。[27]

1917年12月16日,俄國和同盟國之間的停戰協議在布列斯特-立陶夫斯克簽署並開始和談。[28]作為和平的條件,同盟國提出的條約割讓大片前俄羅斯帝國土地給德意志帝國和奧斯曼帝國,極大地刺激了民族主義者和保守主義者。布爾什維克代表列夫·托洛茨基拒絕率先簽署條約並繼續觀察單方面停火,遵循「沒有戰爭就沒有和平」的政策。[29]

由此,1918年2月18日,德國和奧匈帝國在東線展開拳擊行動,德軍接連攻占愛沙尼亞、白俄羅斯及烏克蘭,在最後11天的戰役中幾乎沒有遇到抵抗。[29]簽訂正式的和約對布爾什維克來說是唯一的選擇,因為俄軍被解散,而且新組建的赤衛隊無法阻止戰線推進。他們也認為迫在眉睫的反革命分子的抵抗比承認條約更危險,而前者被列寧看作是世界革命的希望之光中短暫的一瞬。

蘇維埃接受了和約,布列斯特-立陶夫斯克條約於3月6日簽訂。蘇維埃僅僅把條約看作結束戰爭必要的權宜之計。因此,他們割讓了大片土地給德意志帝國,德國在那裡建立了傀儡政權波蘭攝政王國、波羅的聯合公國和立陶宛王國,烏克蘭人民共和國及白俄羅斯人民共和國成立,並受德國保護。

1918年4月紅軍總兵力只有19.6萬人。

在蘇維埃的壓力下,志願軍於1918年2月22日在艱苦卓絕的冰凍三月乘船從葉卡捷琳諾達爾到庫班,在那裡他們加入庫班哥薩克以準備在葉卡捷琳諾達爾的未遂襲擊。[30]蘇維埃在次日奪回了羅斯托夫。[31]科爾尼洛夫將軍在4月13日的戰鬥中被擊斃,而且鄧尼金將軍接管了指揮權。隨着對他們的追蹤者不停息的對抗軍隊成功打通道路撤退到頓河,那裡反抗布爾什維克的哥薩克起義已經開始。

巴庫蘇維埃委員會於4月13日建立。德國的高加索遠征軍於6月8日到達波季。奧斯曼伊斯蘭軍(與阿塞拜疆結盟)於1918年7月26日把他們趕出巴庫。隨後,亞美尼亞革命聯盟、右翼社會革命黨和孟什維克開始和英國在波斯軍隊指揮官鄧斯特維爾將軍協商。布爾什維克和他們的左翼社會革命黨同盟者反對,但7月25日蘇維埃的大部分成員投票表決找英國人,並且布爾什維克放棄。巴庫蘇維埃委員會停止存在並被裏海中部專制政權取代。

1918年6月,約9,000人的志願軍打響了他們的第二次庫班戰役。葉卡捷琳諾達爾在8月1日被包圍並在3日陷落。9月到10月間,阿爾馬維爾和斯塔夫羅波爾發生了激烈的戰鬥。10月13日,卡雜諾維奇將軍的師奪取了阿爾馬維爾,而且在11月1日,彼得·弗蘭格爾保住了斯塔夫羅波爾。這段時間紅軍沒人逃脫,而且在1919年初,整個北高加索從布爾什維克手中解放。

10月,俄國南部白軍領導人阿列克謝耶夫將軍死於心力衰竭。志願軍領袖鄧尼金和頓河哥薩克首領克拉斯諾夫達成協議,全軍統一在鄧尼金的指揮下。南俄武裝力量由此建立。

捷克斯洛伐克軍團的叛變爆發於1918年5月,[32]而且軍團於6月占領了車里雅賓斯克。同時,反布爾什維克的俄國軍官組織設在彼得巴甫洛夫斯克和鄂木斯克。一個月內白軍控制着從貝加爾湖到烏拉爾山區的大部分西伯利亞大鐵路。夏季,布爾什維克在西伯利亞的勢力被清除。西伯利亞臨時自治政府在鄂木斯克成立。

7月底,白軍向西擴展了戰果,於1918年7月6日奪取葉卡捷琳堡。而在1918年7月17日葉卡捷琳堡陷落前不久,前沙皇和家庭被烏拉爾蘇維埃政權處死以阻止他們落入白軍手中。

孟什維克和社會革命黨支持農民反抗蘇維埃控制食物供應。[來源請求]1918年5月,在捷克斯洛伐克軍團的支持下,他們占領了薩馬拉和薩拉托夫,建立了被稱為「科穆奇」的憲法制定議會議員委員會。7月,科穆奇的權力擴展到大部分由捷克斯洛伐克軍團控制的地區。科穆奇實行了矛盾的社會政策,包含了民主主義乃至社會主義的措施,如建立八小時工作日,含有「恢復性」的措施,如歸還工廠和土地給原來的所有者。喀山陷落後,弗拉基米爾·列寧要求派遣彼得格勒工人去喀山前線:「我們必須派遣大多數彼得格勒工人:(1)幾十個像卡尤羅夫那樣的『領導人』;(2)幾千個『來自上層』的」。[33]

經歷了前線的一系列失敗,戰時人民委員托洛茨基建立了越來越多的嚴厲措施以阻止紅軍中未經許可的撤退、逃跑或者叛變。在作戰時,契卡特別偵查部隊,人稱「全俄肅清反革命及怠工非常委員會特別懲罰部」或「特別懲罰旅」跟在紅軍後面,執行現場審理並立即處決從他們的陣地上逃跑、後退或者沒有積極進攻熱情的士兵及軍官。[34][35]托洛茨基拓展了對偶爾撤退或面對敵人逃跑的政治委員的死刑的利用。[來源請求]8月,紅軍部隊持續不斷的戰報中的挫折在戰火中被打破,托洛茨基批准建立督戰隊駐紮在不可靠的紅軍部隊後面,帶有對任何未經批准就從戰線撤退的人射擊的命令。[36]

1918年9月,西伯利亞臨時政府科穆奇和其他反布爾什維克政府在烏法開會並同意在鄂木斯克組建新的臨時全俄政府,由五人內閣領導:三位社會革命黨員(尼古拉·阿夫克先季耶夫、瓦西里·博爾德列夫和弗拉基米爾·津濟諾夫)和兩位立憲民主黨員(V·A·維諾格拉多夫(V. A. Vinogradov)和P·V·沃洛戈茨基(P. V. Vologodskii))。

1918年末,東部反布爾什維克白軍包括了人民軍(科穆奇)、西伯利亞軍(屬西伯利亞臨時政府)和奧倫堡哥薩克起義軍及西伯利亞、七河流域、貝加爾、阿穆爾及烏蘇里哥薩克,名義上受烏法內閣任命的總司令V·G·博爾德列夫將軍指揮。

在伏爾加流域,弗拉基米爾·卡普佩爾上校於8月7日奪取了喀山,但紅軍於1918年9月8日隨反攻奪回這座城市。11日,辛比爾斯克陷落,10月8日,薩馬拉陷落。白軍向東撤退到烏法和奧倫堡。

在鄂木斯克,全俄臨時政府很快受到了新的戰爭部長海軍少將高爾察克的影響。11月18日,高爾察克發動政變成為獨裁者。內閣成員被捕,高爾察克宣布成為「俄國最高統治者」。

1918年2月紅軍推翻了白俄支持的突厥斯坦的浩罕自治政府。[37]即使這一行動看起來鞏固了布爾什維克在中亞的勢力,更多的問題像盟軍的介入一樣降臨到紅軍面前。1918年英國支持的白軍給中亞的紅軍造成了極大的威脅。英國向那裡派出了三位傑出的指揮官。一位是貝理中校,他從布爾什維克強行驅趕他的地方記錄了一次去塔什干的任務。另一位是馬里遜將軍,他領導了以一小隊英裔印軍援助阿什哈巴德(今土庫曼斯坦首都)的孟什維克的馬里遜行動。然而他失去了對塔什干、布哈拉和希瓦的控制。第三位是鄧斯特維爾少將,他在1918年8月到達以後僅用一個月就把布爾什維克趕出中亞。[38]即使1918年因為英國的介入造成的曲折,布爾什維克仍繼續以他們的影響力對中亞人民開展行動。俄國共產黨第一次地方代表會於1918年6月在塔什干召開,為了支援當地的布爾什維克黨。[39]

7月,兩位左翼社會革命黨和契卡成員布柳姆金和安德列耶夫暗殺了德國大使米爾巴赫。在莫斯科左翼社會革命黨起義被布爾什維克利用契卡軍事派遣鎮壓。列寧親自就暗殺事件向德國道歉。隨後大規模逮捕社會革命黨員。

愛沙尼亞於1919年1月趕走了紅軍。[40]波羅的海德意志志願軍於5月22日從紅色拉脫維亞步兵團奪取了里加,但是愛沙尼亞第3師一個月後擊敗了波羅的海的德意志人,有力支持了拉脫維亞共和國的成立。[41]

紅軍遇到了另一個潛在威脅——來自尤登尼奇將軍,他用一個夏天的時間在愛沙尼亞組織北部軍隊並獲當地英國人的支持。1919年10月,他嘗試用約20,000人的兵力以突然襲擊奪取彼得格勒。進攻很利落,用夜襲和騎兵閃電般的行動轉變側翼打敗紅軍。尤登尼奇還有6輛英國坦克,這在它們出現的時候造成了恐慌。協約國給尤登尼奇給予了大量支援,然而尤登尼奇抱怨收到的援助不夠。

10月19日,尤登尼奇的部隊到達城市郊區。一些莫斯科布爾什維克中央委員會委員想放棄彼得格勒,但托洛茨基拒絕接受城市的丟失並親自組織反攻。他宣稱,「讓15,000名退役軍官組成的小分隊去掌握700,000居民的工人階級資產是不可能的。」他制訂了在市區防守的策略,宣稱這座城市將「在自己的地盤上捍衛自己」並且白軍在加築工事的街道的迷宮中迷失並「填滿墓穴」。[42]

托洛茨基把所有能拿起武器的男女工人武裝起來,下令從莫斯科調兵。僅僅幾個星期內紅軍就守住了彼得格勒並擴充了三倍於尤登尼奇的兵力。此時尤登尼奇缺乏物資,決定轉移城市的包圍圈並撤軍,反覆請求愛沙尼亞允許他的軍隊撤到邊境上。然而,軍隊撤退經過邊境就被愛沙尼亞政府下令解除武裝並拘捕,他們於9月16日與蘇俄政府加入了和談,且蘇俄當局11月6日通報了萬一白軍從邊界撤入愛沙尼亞,紅軍將越境抓捕的決定。[43]事實上紅軍攻擊了愛沙尼亞軍隊的陣地,而且戰鬥一直持續到1920年1月3日停火生效。許多尤登尼奇的士兵隨着塔爾圖和約的簽訂而被流放。

芬蘭將軍曼納海姆制定過芬蘭人干涉支持俄國白軍奪取彼得格勒的計劃。他沒有執行,卻努力給予支持。列寧認為「完全肯定,來自芬蘭的最細微的援助都能決定彼得格勒的戰敗」。

1918年底蘇俄紅軍總兵力已增至300萬人。

1919年3月初,白軍在東線發起總攻。3月13日奪回烏法;4月中旬,白軍被阻滯在格拉佐夫-奇斯托波爾-布古利馬-布古魯斯蘭-沙爾雷克一線。紅軍在4月底展開對高爾察克部隊的反攻。紅軍在猛將圖哈切夫斯基的指揮下,於5月26日奪權葉拉布加,6月2日奪取薩拉普爾,7日奪取伊熱夫斯克並繼續推進。雙方都有勝利和損失,但在夏季的中旬紅軍的規模超過了白軍並設法奪回先前失去的土地。

隨着在車里雅賓斯克的失敗的進攻,白軍退到托博爾河周邊地區。1919年9月,白軍在托博爾河展開進攻,最後一次嘗試改變戰況。但在10月14日,紅軍發起反攻並開始了白軍向東的持續撤退。

1919年11月14日,紅軍奪取了鄂木斯克。[44]海軍上將高爾察克在這次失敗後失去了對他的政府的控制,西伯利亞的白軍部隊在12月被徹底消滅。白軍的東線撤退持續了3個月,直到1920年2月倖存者經過貝加爾湖到達赤塔並加入了格里戈里·謝苗諾夫的軍隊。

1918年末哥薩克無法組織起來並爭取勝利。1919年他們開始出現物資短缺。因此,當蘇俄在布爾什維克領導人安東諾夫-奧夫謝延科的領導下於1919年1月發起反攻的時候,哥薩克武裝土崩瓦解。紅軍於1919年2月3日奪取基輔。

鄧尼金的武裝力量在1919年春季持續擴張。在1919年冬春之交的幾個月裡,局勢難料的惡戰發生在頓巴斯,那裡正在進攻的紅軍遭遇了白軍。同時,鄧尼金的南俄武裝力量完成了對北高加索紅軍的殲滅並向察里津進軍。在4月底5月初,南俄武裝力量在從第聶伯河到伏爾加河的所有戰線進攻,而且在夏季開始的時候他們贏得了多次戰役。法軍抵達敖德薩但後來幾乎沒有戰鬥,1919年4月8日撤軍。6月中旬紅軍從克里米亞和敖德薩被追趕。鄧尼金的部隊奪取了哈爾科夫和別爾哥羅德。同時白軍在弗蘭格爾的指揮下於1919年6月17日占領察里津。6月20日,鄧尼金發出「進軍莫斯科令」,命令所有南俄武裝力量準備進軍莫斯科。

英國即使從戰區撤軍,仍在1919年給白軍留下重要的軍事援助(錢、武器、食物、軍火和一些軍事顧問)。

奪取察里津後,弗蘭格爾向薩拉托夫推進,但托洛茨基看到他和高爾察克聯合會命令集中大規模兵力對付紅軍的危險,以巨大的損失擊退了他的進攻。當高爾察克的軍隊在6-7月開始向東撤退,大部分紅軍在西伯利亞的威脅被解除,集中對付鄧尼金。

鄧尼金的武裝構成了真正的威脅,並且隨着時間的推移而威脅到莫斯科。紅軍因各條戰線的戰鬥被削弱,8月30日被打出基輔。庫爾斯克和奧廖爾被奪走。哥薩克武裝頓河軍在康斯坦丁·馬蒙托夫將軍指揮下繼續向北進軍沃羅涅日,但圖哈切夫斯基的軍隊於10月24日在那裡擊潰了他們。圖哈切夫斯基的軍隊轉向了另一個威脅,鄧尼金將軍重建的志願軍。

白軍反抗蘇維埃的高潮在1919年9月打響。當時鄧尼金的武裝危險地過度擴展。白軍前線沒有縱深或者穩定:那裡成為一連串進展很慢沒有後備的臨時縱隊的巡邏。缺乏彈藥、火炮和新的後援,鄧尼金的武裝在1919年10月和11月的一系列的戰役中決定性地潰敗。紅軍於12月17日奪回了基輔,而且戰敗的哥薩克向後逃往黑海。

當白軍在中部和東部被擊潰的時候,他們成功的把內斯托爾·馬赫諾的無政府主義黑軍(正式名稱為烏克蘭革命起義軍)趕出了烏克蘭南部和克里米亞。儘管這樣的挫折,莫斯科拒絕援助馬赫諾和黑軍並拒絕給烏克蘭無政府主義武裝提供武器。

白軍主力志願軍和頓河軍向頓河後撤,到羅斯托夫。一小部分(基輔和敖德薩部隊)撤到敖德薩和克里米亞,前者在1919–1920年冬季阻滯了布爾什維克。

1919年2月英國政府從中亞撤軍。[45]即使這對於紅軍來說是個勝利,白軍在俄國歐洲部分及其他地區的進攻打斷了莫斯科與塔什干之間的聯繫。一段時間來,中亞地區已經完全從西伯利亞的紅軍部隊中被切斷。[46]即使通訊上的失敗削弱了紅軍,布爾什維克仍然通過3月召開的第二屆黨代會努力支持布爾什維克黨組織。這次會議上俄國布爾什維克黨的穆斯林區域辦事機構成立。布爾什維克黨繼續通過對中亞人民更好的表現及保持中亞人民的融洽留下印象嘗試並給予當地人民支持。[47]

西伯利亞和俄國歐洲部分的紅軍部隊通訊上的困難在1919年11月中結束。因為紅軍在中亞北部取得了成功,與莫斯科的聯繫得到重建,並且布爾什維克宣布在突厥斯坦戰勝白軍。[46]

1920年之始,南俄紅軍主力迅速地向頓河撤退,到羅斯托夫。鄧尼金希望控制住頓河的渡口,並重組他的部隊,但白軍無法控制頓河流域,並在1920年2月底開始經庫班向新羅西斯克撤退。新羅西斯克的草率疏散被證明對白軍是黑暗的。約40,000人通過俄國和同盟國船隻從新羅西斯克撤到克里米亞,沒有馬匹或任何重武器,同時約20,000人留下來並解散或者被紅軍俘獲。

隨着慘痛的新羅西斯克撤退,鄧尼金退出,軍事委員會選舉弗蘭格爾為白軍新的總司令。他能恢復對士氣低落的部隊的指揮並能讓部隊重新以常規武裝的姿態繼續戰鬥。這在1920年間在克里米亞維持了有組織的武裝力量。

在莫斯科的布爾什維克政府與內斯托爾·馬赫諾和烏克蘭無政府主義者簽訂軍事和政治同盟後,黑軍在烏克蘭南部攻擊並戰勝了弗蘭格爾部隊的幾個團,迫使他在他能奪取當年收穫的糧食之前撤退。[48]由於他努力鞏固自己的控制,弗蘭格爾後來向北進攻以試圖利用近期紅軍在1919–1920年波蘇戰爭結束時失利的優勢。這次攻勢最終被紅軍阻止,而且弗蘭格爾的部隊被迫於1920年11月撤到克里米亞,被紅軍和黑軍的騎兵和步兵追趕。弗蘭格爾及其殘餘勢力於1920年11月14日從克里米亞撤到君士坦丁堡。由此紅軍和白軍在俄國南部的戰鬥結束。

打敗弗蘭格爾後,紅軍立刻撕毀了1920年和內斯托爾·馬赫諾的盟約並攻擊無政府主義黑軍;清除馬赫諾和烏克蘭無政府主義者的戰役隨着契卡特工對馬赫諾的未遂暗殺開始。由於被布爾什維克共產主義政府的持續鎮壓及其任用契卡消滅無政府主義分子激起的憤怒,喀琅施塔得爆發水兵暴動,隨後是農民起義。紅軍在1921年殘忍地加強了對無政府主義武裝及其支持者的進攻。

在西伯利亞,海軍上將高爾察克的軍隊被擊潰。他在失去鄂木斯克和任命格里戈里·謝苗諾夫為西伯利亞白軍新的指揮官後放棄了指揮權。不久,高爾察克在他沒有軍隊保護下抵達伊爾庫茨克並在伊爾庫茨克被憤怒的捷克斯洛伐克軍團逮捕,之後被移交給社會革命黨的政治中心。六天後,這一政權被布爾什維克控制的軍事革命委員會取代。2月6日至7日間,在白軍到達之前,高爾察克和他的總理維克托·佩佩利亞耶夫被擊斃,屍體從冰面被扔進冰冷的安加拉河。[49]

高爾察克的殘餘部隊到達外貝加爾山脈並加入格里戈里·謝苗諾夫的軍隊,組成遠東軍。在日本的支持下,他們能守住赤塔,但日本從外貝加爾山脈撤軍後,謝苗諾夫的軍隊無法堅持,他在1920年11月被紅軍擊敗,併到中國避難。曾計劃吞併阿穆爾的日本人最終在布爾什維克軍隊逐漸地掌控俄國遠東地區時撤兵。1922年10月25日,海參崴落入紅軍手中,阿穆爾河沿岸臨時政府滅亡。

內戰結束前,紅軍總兵力550萬人。

在中亞,紅軍仍在1923年面臨抵抗,在那裡巴斯瑪奇(伊斯蘭游擊武裝)建立起來並襲擊布爾什維克接管的地區。蘇維埃在中亞雇用了非俄羅斯族人來抵抗巴斯瑪奇,如東干騎兵團的司令馬三奇。直到1934年共產黨都沒有完全解散這一小組。[50]

安納托利·佩佩里亞耶夫在阿揚-邁斯基區堅持武裝抵抗到1923年6月。而庫頁島北部仍被日本占領,直到1925年日本和蘇聯簽訂條約為止。

內戰造成的後果很嚴重。蘇聯人口統計學家鮑里斯·烏爾拉尼斯估計內戰和波蘇戰爭總共造成300,000人(紅軍125,000人,白軍和波蘭人175,500人)被殺,雙方死於疾病的軍事人員總共有450,000人。[51]

紅色恐怖期間,契卡就地處決了「階級敵人」至少250,000次,據估計死者有一百萬人以上。[52][53][54][55]

300,000–500,000哥薩克被殺或在去哥薩克化運動中被驅逐,人數超過三百萬。[56]據估計100,000名猶太人在烏克蘭被殺,許多人死於紅軍之手。[57]1918年5月至1919年1月間頓河哥薩克的刑罰機構處死了25,000人。[58]高爾察克政府僅在葉卡捷琳堡省就擊斃了25,000人。[59]

內戰末期,蘇俄被耗竭且近乎毀滅。1920至1921年的乾旱以及1921年的饑荒使災難更為嚴重。疾病大規模流行,僅1920年就有3,000,000人死於斑疹傷寒。一百多萬人還死於大規模饑荒、交戰雙方的大規模屠殺和烏克蘭和南俄對猶太人的迫害。1922年,世界大戰和內戰將近10年的破壞造成俄國有至少7,000,000流浪兒。[60]

另外1到2百萬被稱作白俄的人離開俄國——許多跟隨弗蘭格爾出逃,一些經過遠東,其他人向西到達新獨立的巴爾幹國家。這些人又有不少是在俄國受過良好教育的專業人士。

俄國經濟被戰爭徹底破壞,工廠和橋梁被破壞,牲畜和原材料被掠奪,礦場被淹沒,機器被毀。工業產值降至1913年的七分之一,農業產值降至三分之一。根據《真理報》,「城鎮的工人和一些村莊在飢餓的劇痛中窒息,鐵路勉強能通車,房屋倒塌,城鎮充滿了廢物,傳染病蔓延且死亡降臨——工業被破壞了。」[來源請求]

據估計1921年工礦總產量下降到世界大戰之前水平的20%,而且許多重要的項目經歷了一次更劇烈的衰退。例如,棉花產量下降到5%,鋼鐵下降到戰前水平的2%。

戰時共產主義在戰爭期間挽救了蘇維埃政權,但大部分的俄國經濟停滯不前。農民以拒絕耕種土地回應征糧。1921年,耕地規模降至戰前的62%,而且收穫量僅有正常時期的37%。馬匹的數量從1916年的3500萬降至1920年的2400萬,牲畜從5800萬降到3700萬。美元匯率從1914年2盧布降到1920年1,200盧布。

隨着戰爭的結束,共產黨不再遭遇對其存在和權威的激烈的軍事威脅。然而,另一次干預威脅,加上其他國家社會主義革命的失敗,尤其是德國革命,促成蘇俄社會持續的軍事化。即使俄國經歷了快速的經濟增長,一戰和內戰的共同影響在1930年代給俄國社會留下了持久的傷疤,並對蘇聯的發展造成持久的影響。

俄國內戰期間,波蘭通過波蘇戰爭占領了西烏克蘭和西白俄羅斯的近46萬平方公里土地,但由於波蘭領土為恢復到其亡國之前的疆域,所以波蘭政府一直在計劃進一步進攻蘇聯,蘇聯政府也以為波蘭占領蘇聯領土而對波蘭持敵視態度,但蘇聯直到1939年才重新控制了這些地區。

1917年10月——克倫斯基和他的支持者逃出彼得格勒。

1918年1月5日——赤衛隊在列寧的指揮下破壞制憲會議。

1918年1月28日——托洛茨基創建紅軍。

1918年3月——布爾什維克為了安全和更好的通信從彼得格勒遷都莫斯科,以其在領土的中心。

1919年10月14日——鄧尼金的軍隊逼近距莫斯科300公里的奧廖爾。

1919年10月22日——白軍逼近彼得格勒郊區,托洛茨基組織反擊。

1919年11月初——西方盟國為白軍提供支援。

1920年2月7日——高爾察克在被捷克軍團移交後被布爾什維克逮捕。

1920年4月——波蘭人被布爾什維克趕回波蘭。

1921年——一些人繼續戰鬥,但白軍被擊潰。

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.