无神论

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

无神论(英语:atheism),在广义上,是指一种不相信神存在的观念[1][2][3][4][5];在狭义上,无神论是指对相信任何神鬼存在的一种抵制[6][7]。无神论与通常至少相信一种神存在[8][9][10]的有神论相对[8][11][12]。

对于神(上帝)和灵魂存在,有着各种各样截然不同的概念,导致了无神论的适用性的各种观点。但狭义的无神论否认的事物包括:从神的存在到任何超自然或先验概念的存在,例如印度教、佛教和道教的观念。[13]也因此部分学者主张,从哲学观点来研究所谓坚持无神主义的人或是政治组织,本身亦是持一种如信仰一般的理念存在,并在实务上表现出了类似的行为模式。[14]

简介

支持无神论的论据包括各类从哲学到社会和历史的方法。无神论者不相信神存在,因为其缺乏经验证据的支持[15][16]、无法解释罪恶问题、各种神的启示不一致、不可证伪、且没有考虑无信仰者[15][17]。无神论者认为,无神论比有神论更简约,而且每个人生来就没有对神灵的信仰[18];因此,他们认为驳斥神灵存在的举证责任不在无神论者身上,而是应由有神论者证明有神论正确[19]。虽然一些无神论者采用了世俗主义哲学(例如世俗人文主义)[20][21],无神论者之间并没有一个共同的思想体系[22]。

20世纪英国的著名哲学家伯特兰·罗素用其罗素的茶壶的例子说明,任何人都没有反证断言的责任,论证有神论者这一立场的错误。道金斯进一步用飞天面条神教和罗素的茶壶作为一个反证法的论述有神论者这一立场的错误,如果在无法由科学证明的情况要求相信和不相信一个超自然存在都得到同样的尊重和重视,那么它也必须给予相信罗素的茶壶存在同等的尊重,因为茶壶和超自然存在同样无法去由科学证明或否证[23]。伯特兰·罗素还在其《为什么我不是基督徒》一书中,以科学求证的态度否定超自然性和上帝[24]。在一篇成于1952年但从未发表的文章《神存在吗?》里,罗素写到:

我应称自己为不可知论者;但在实际意义上,我是无神论者。我不认为基督教中的神比奥林匹斯十二主神或瓦尔哈拉更可能存在。用另一个例证:没有人可以证明,在地球和火星之间没有一个以椭圆形轨道旋转的瓷制茶壶,但没人认为这充分可能在现实中存在。我觉得基督教的上帝一样不可能。[25]

有“现代物理学之父”之誉的爱因斯坦在其作品《我的世界观》中是这样否定上帝: “我无法想象存在这样一个上帝,它会对自己的创造物加以赏罚……我不能也不愿去想象一个人在肉体死亡以后还会继续活着。”但事实上,爱因斯坦形容自己为不可知论者,并不同意专业无神论者般的十字军精神;更仔细解释,由于人类对于大自然与自己本身的了解可能有缺失,因此应该采取谨慎谦卑的态度。美国犹太领袖拉比赫伯特·高德斯坦曾经问他是否相信神?他回答说:“我相信斯宾诺莎的神,一个通过存在事物的和谐有序体现自己的神,而不是一个关心人类命运和行为的神。”换句话说,爱因斯坦认为,从宇宙世界的存在,可以感觉到神的伟大工作,但神并不会干预人们的日常生活,神是非人格化的神[26]:389-390。爱因斯坦曾经在书信里表示:“我不相信人格化的神,我从未否认这一点,而且表达得很清楚。如果在我的内心里有什么能被称之为宗教,那就是,对于我们的科学所能够揭示的世界结构,对于这世界结构的无垠的敬仰。”[27]:43[28]

物理学家霍金在其2010年《大设计》一书中论证宇宙可依照科学原理而浑然天成,不须向上帝过问,甚至没有所谓造物主的位置[29]。

21世纪初的一群无神论作家所提出新无神论的思想。他们主张“对宗教在政府,教育和政治等任何施加不适当影响的任何地方,它不应该是简单地被容忍,而应该受反驳、批评,并暴露于理性的争论之下。”有媒体将丹尼尔·丹尼特、理查德·道金斯、山姆·哈里斯及克里斯托弗·希钦斯被称为“新无神论的四骑士”[30]。以前的作家中的许多人认为科学不关心甚至无法处理“神”的概念,理查德·道金斯则相反,声称“神假说”是有效的科学假说,对物理的宇宙有影响,像其他任何科学假设一样都可以得到检验和证伪。道金斯以其直言不讳的语气和科学求证的态度挑战“神创造世界”宗教概念而闻名[23]。他们在2004年至2007年间写下的一些畅销书为新无神论的后续讨论奠定了理论基础。随着时代发展和科学进步的影响,教皇现在希望大众接受进化论和大爆炸理论[31]。

1979诺贝尔物理学奖获得者史蒂文·温伯格警示人们,世界需要从漫长的宗教信仰噩梦中醒来;对我们科学家来说,为削弱宗教信仰而可以做的任何事情都应该去做,实际上这可能是我们对文明的最大贡献。宗教是弊大于利的[32]。他还认为:无论有没有宗教,好人都会做好事,坏人都会做恶事;但是,若你想要好人做恶事,就需要宗教了[33]。

由于对无神论的定义各不相同,因此很难准确估计目前无神论者的人数[34]。根据温—盖洛普国际在全球范围内的研究显示,2012年有13%的受访者是“坚定的无神论者”[35],2015年有11%是“坚定的无神论者”[36],2017年有9%是“坚定的无神论者”[37]。其他研究人员建议谨慎对待温—盖洛普国际的统计数字,因为几十年来使用相同统计方法且样本量更大的其他调查得出的数字一直偏低[38]。英国广播公司2004年进行的一个调查显示,无神论者为全世界人口的8%[39]。其他较早的估计表明,无神论者占世界人口的2%,而无宗教者占12%[40]。这些民调显示欧洲和东亚是无神论占比最高的地区。2015年,中国有61%的人报告称他们是无神论者[41]。2010年欧洲联盟的欧洲晴雨表调查数字显示,20%的欧盟人口声称不相信“任何种类的灵魂、神或生命力”的存在,其中法国(40%)和瑞典(34%)占比最高[42]。

跨国研究结果表明教育程度和不相信上帝有正相关性[43][44],事实上无神论在科学家中所占地比例更高这一趋势在20世纪初就比较明显,而到20世纪末成为科学家中的多数。美国心理学家詹姆士·柳巴1914年随机调查1000位美国自然科学家,其中58%“不相信或怀疑神的存在”。同一调查在1996年重复了一次(《自然》杂志1998年刊登的文章)[45],得出60.7%的类似结果, 而且美国科学院院士中这一比例高达93%。肯定回答不相信神的比例从52%升高至72%。调查显示美国国家科学院院士之中相信人格神或来世的人数处于历史低点,相信人格神的只占7%,远低于美国人口的85%比例。

对无神论的批评也不无存在。例如,批评者认为主张无神论者自身也无法确证神不存在,无神论相信神不存在本身就很接近一种宗教式的信条[46]。美国土耳其裔物理学家、怀疑论者坦纳·埃迪斯就认为,没有证据表明科学离不开无神论。他认为无神论大部分推论都是基于伦理学、或者哲学的推理[47]。启蒙运动思想家、唯物主义哲学家德尼·狄德罗也对无神论持批评态度。他不认为无神论比形而上学更科学[48][49]。

词源

在早期古希腊语中,形容词“atheos”(ἄθεος),由否定词缀ἀ- + θεός“神”构成)的意思是"不敬畏神的"或"邪恶的"。公元前五世纪以后该词的意思逐渐的演变成了“有意的无神”,成为“与神断绝关系”或“否认神的存在”而不再是早期的ἀσεβής(asebēs,不虔诚的)。古希腊文的现代翻译通常会将“atheos”译作“无神论的”,而ἀθεότης(atheotēs)则译作抽象名词“无神论”。西塞罗把atheos这个希腊语词汇转写成拉丁形式atheos。在早期天主教与古希腊宗教的辩论中常常能看见这个词,双方都以此轻蔑对方[51]。

在英语中,无神论一词来自于1587年左右的法语词汇athéisme[52]。而无神论者一词(来自法语“athée”,意为“否认或拒绝相信神的存在的人”)[53]在英语中出现的比无神论更早,大约在1571年[54]。无神论者最早在1577年开始被当作不信神者的标签[55]。相关的词语则在其后出现:自然神论者,1621年[56],有神论者,1662年[57];有神论,1678年[58];自然神论,1682年[59]。1700年左右,在无神论一词的影响下,自然神论和有神论的词义发生了轻微的变化;自然神论的本义与有神论完全相同,但却有了独立于有神论的哲学意义[60]。

凯伦·阿姆斯特朗曾记载:“在16到17世纪之间,无神论者一词仍然只能在辩论中见到……被唤做无神论者是个巨大的侮辱。没有人愿意被称为无神论者。”[61]无神论在18世纪晚期的欧洲被首次用作自称,但当时该词的含义特指不信仰亚伯拉罕诸教[62]。随着20世纪全球化的趋势,无神论一词的意思被扩大到了“不信仰任何宗教”,然而在西方社会,该词还是主要用以描述“对上帝的不信仰”[63]。

认识论基础

无神论用形而上学[64]的理性分析和科学检验的方法,不靠没有证据的信仰,旨在坚持与其他哲学(如形而上学和不可知论)和科学事业相同的理性调查标准,并接受相同的评估和批评方法。这种认识论上的理性的分析方法,也被哲学家和神学家用来研究信仰的本身的合理性,将宗教经典的描述和历史,考古,和科学发现相比较。

无神论遵循的推理方法类似于自然神论[65]和不可知论,避免了吸引特殊的非自然才能(心灵感应,神秘经历)或超自然的信息来源(神圣的文本,神学的揭示,信条权威,直接的超自然交流)。这种避免非自然才能或超自然的信息来源的方法,与启示神学和基督教神学的方法有区别。

无神论的理性分析和科学检验的方法与靠信仰的方法相对立。伯特兰·罗素写道:基督徒认为自己的信仰行善,但其他信仰却有害,无论如何,他们对共产主义信仰也是持这种观点。我坚持的是,所有信仰都是有害的。我们可以将“信仰”定义为对没有证据的事物的坚定信念,在有证据的地方,没有人会说“信仰”。我们不说“2加2等于4”是信仰,也不说“地球是圆的”是信仰。我们只在希望用情感代替证据时才谈到信仰,用情感代替证据容易导致冲突,这是因为不同的群体用不同的情感来代替。基督徒对信仰耶稣复活,共产党人相信马克思的价值论。其中任一种信仰都不能得理性的支撑,因此,每种信仰都只得通过宣传来维持,必要时还得通过战争[66]。

进化生物学家理查德·道金斯在其著作《上帝错觉》中批判他所认为的与科学证据直接冲突的所有信仰[67]。他将信仰描述为没有证据的盲信,一个积极的不思考的过程。他指出,这种做法只会让任何人仅凭个人思想和可能扭曲的感知(不需要对自然进行检验)提出关于自然的断言(主张); 这种做法,降低了我们对自然世界的理解,没有任何能力做出可靠且一致的预测,并且无需同行评议[68]。

定义与区分

不同的无神论者信仰不同的超自然实体,不同的无神论对信仰有着不同的界定,考虑到这些问题,人们很难直接的定义与区分无神论[69]。

定义区分无神论时有许多困难,主要因为对如神与上帝等基本概念的定义没有一致共识,对神定义的多样性相应的导致了对无神论定义的不同。古罗马因为基督徒拒绝信奉古罗马宗教而指责其为无神论者,而在20世纪,无神论一词则更多的被理解为不信仰任何宗教[70]。

对无神论的定义存有一个问题,那就是一个无神论者对神的“不信”需要到一个什么程度。无神论的定义有时包括了对有神信仰的简单缺失。这个宽泛的定义可以把连同新生儿在内的许多从未为接触过有神论概念的人涵盖进去。如1772年霍尔巴赫所说:“儿童生来即是无神论者;他们对上帝(是什么)没有概念。”[72]同样地,乔治·H·史密斯在1979年说道:“对有神概念不熟悉的人即为无神论者,因为他不信神。这个分类同样包含了那些已经有能力去把握,但实际上并没有清楚意识到神灵概念的儿童们。儿童们对神的不信仰使他们成为了无神论者。”[73]史密斯创造了隐无神论一词表示“缺乏信仰但并非有意抵制”,同时也创造了显无神论指代“对自己的不信仰有明确意识”。

在西方文化中,儿童生来即为无神论者的观点出现的相对较晚。在18世纪以前,西方对上帝存在的信仰是如此广泛,以至于是否存在真正的无神论者也值得怀疑。这被称为神学天赋论——一种认为人生来就信仰上帝的观点;这种观点简单地否定了无神论者的存在[74]。还有一种观点认为无神论者在遇上危难时将很快地投身信仰,例如做出临终皈依,一句西方谚语“散兵坑里没有无神论者”也阐述了这一观点[75]。这一观点的部分支持者认为宗教在人类学意义上的益处是宗教信仰能让人更好的面对逆境(对比卡尔·马克思在《黑格尔法哲学批判纲要》中提出的精神鸦片说)。一些无神论者则强调实际上有反例,确实存在着“散兵坑里的无神论者。”[76]

哲学家安东尼·弗鲁[77],迈克尔·马丁(Michael Martin)[63],以及威廉·L·罗伊(William L. Rowe)[78]等人将无神论分为强(积极)与弱(消极)两类。强无神论清楚地宣称神不存在,弱无神论则包含了所有形式的非有神论。根据此分类,所有的非有神论者都必然是强或弱无神论者[79],而绝大多数不可知论者都是弱无神论者。与积极和消极相比,强和弱两词用以形容无神论则相对较晚,但至少在1813年[80][81]就已经出现在了各类(虽然用法略有不同)哲学著作[77]与天主教的辩惑[82]之中。

当马丁等哲学家把不可知论归类为弱无神论的时候[70],绝大多数的不可知论者并不认为自己是无神论者,在他们看来无神论并不比有神论更加合理[83]。支持或否定神存在的知识的不可获得性有时被看作无神论必须经历“信仰飞跃(Leap of Faith)”的标示[84]。一般无神论者对这一论证的反驳包括:未经证实的宗教命题应和其他的未证实命题受到同样多的怀疑[85],以及神存在与否的不可证明性并不代表两种可能的概率相等[86]。苏格兰哲学家J. J. C.斯马特甚至说道:“因为一种过于笼统的哲学怀疑论,有时一个真正的无神论者可能会,甚至是强烈地,表达自己为一个不可知论者,这种过分的怀疑论将阻碍我们肯定自己对或许除数学或逻辑定理以外的任何知识的理解。”[87]因此,一些知名的无神论作家如理查德·道金斯更倾向于依据“有多大程度相信神存在”的光谱来区分有神论者,不可知论者与无神论者。[88]

如上文所述,积极和消极两词与强和弱两词在形容无神论时具有相同意义。但是印度哲学家拉奥 (哲学家)在其1972年出版的《积极无神论》一书中给出了此词语的另一种用法[89]。古拉本人在阶级划分明显与宗教文化底蕴深厚的印度长大,在他的努力下印度建立起了一个世俗政府,据此他提出了一些积极无神论哲学的指导方针[90],积极无神论者应该具有这样一些品质:品行正直,对有神论者理解,不强求他人成为无神论者,以及对真理的追求,而不是满足在争辩中的胜利。

基本理据

‘那是你身体的父亲,而那,是你灵魂的父亲。’

男孩回答道:

‘在我之上的是什么与我无关,而我为我是这样一个老人的孩子而感到羞愧!’

‘噢,这是何等不敬啊,不愿承认你的父亲,也不愿承认神才是你的创造者!’”[91] 此寓意画阐明了实用无神论和其在历史上与不道德的关联,该寓言原标题为“极端的不敬:无神论和骗子”,取自1552年由巴泰勒米·阿诺所作的《空想诗集》。

信仰无神论的哲学理据在大体上可划分为实用主义和理论主义两类,而各种不同理论的无神论又分别来自独一的论据与哲学论证。与此相反,实用无神论不需要论证,因为其核心概念是对有神论概念的漠视和无知。

在实用,或称实用主义无神论体系中(又称远神论),个人的生活不受神灵的影响,对日常现象的解释也不用借助神学。但神的存在并未遭到直接否认,而仅仅被认为无需考虑;在这种观点下,神既不为个人生活提供目标,也不影响个人的日常生活[92]。对科学界造成影响的一种实用无神论叫做方法论自然主义—即“无论是否全然接收与认可,对科学方法内的哲学自然主义的接纳和假设。”[93]

实用无神论有多种表现形式:

- 缺乏宗教积极性—对神的信仰并未推动其道德行为,宗教行为及任何形式的行为;

- 用思想和实际行动主动排斥与神与宗教有关的问题;

- 冷漠—对有关神和宗教的议题缺乏关心;

- 对神的概念不了解[94]。

理论主义无神论要求清晰的提出神不存在的证明,以回应诸如目的论论证与帕斯卡的赌注一类神存在的论证。否认神存在的论据有很多种,通常是以本体论,认识论以及知识论的形式表现,但有时也会表现在心理学与社会学的形式上。

知识论无神论认为人不可能感知到神祇或其存在,其理论基础为不同形式的不可知论。在内在理论体系中,神与世界是紧密相连的,因此也存在于人的思想中,与此同时,每个人的意识又都必然是主观的;根据这种不可知论,人类认知所存在的种种限制使得来自宗教信仰的任何客观推理都无法得出神存在的结论。康德的理性主义不可知论和启蒙运动只接受人类理性推导得出的知识;这一类无神论认为神不像原则问题般清晰可辨,因而不能确知其是否存在。基于休谟理念的怀疑主义断言确知任何事物都是不可能的,因而人永远不能知道神是否存在。对无神论和不可知论的分类饱受争议;两者能被看成是不同且相对独立的世界观[92]。

其他的能被分类成知识论或本体论的?无神论论证,包括逻辑实证主义和漠视主义,都论述了例如“神”和“神是全能的”一类概念和陈述的无意义性及不清晰性。神学非认知主义认为“神存在”这一类陈述并未表达任何主张,实际上是荒谬无意义的。神学非认知主义应该被分类为无神论还是不可知论一直存有争议。哲学家艾尔弗雷德·朱尔斯·艾耶尔和西奥多·迈克尔·德兰格反对这两种分类,他们认为这两种理论都接受“神存在”是一种主张;因而坚持神学非认知主义的独立性[95][96]。

形而上学无神论是建立在形而上学一元论——一种认为世界是同质且不可分的概念——的基础上的。绝对形而上学无神论者相信多种不同形式的物理主义,并据此否认非物理的存在。相对形而上学无神论者对神的概念则持有较为缓和的否定态度,这种否定态度来源于他们的哲学信仰与神的超然存在或人格等属性之间的矛盾。相对形而上学无神论包括了泛神论,超泛神论以及自然神论[97]。

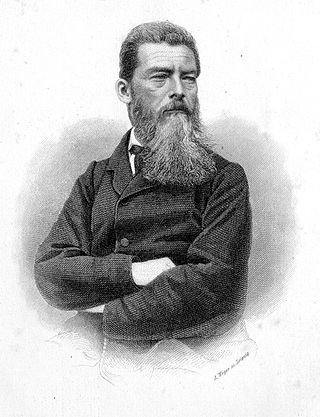

哲学家如路德维希·费尔巴哈[99]与西格蒙德·弗洛伊德认为上帝和其他宗教信仰都是人类自身的创造,其目的是填补许多心理与情感上的需求。这也是许多佛教徒的观点[100]。受费尔巴哈的影响,卡尔·马克思和弗里德里希·恩格斯研究神与宗教的社会功能并作出结论,认为它们是统治阶级用来压迫劳动阶级的工具。米哈伊尔·巴枯宁则说:“神的概念暗指了人类理性和公义的缺失;它是对人类自由的极端否定,不论在理论上还是在实际中,它都必随着人类奴役的结束而消亡。”他将伏尔泰的名言“如果上帝不存在,那就必须创造祂。”修改成“如果上帝存在,那就必须抛弃祂。”[101]

基于逻辑学的无神论认为对神的概念的各种不同定义——例如基督教的人格神——都在逻辑上有自相矛盾的本质。这一类无神论者提出了各种演绎论证来否定神的存在,此类论证明确了神的几种属性,例如:完美、创造者地位、不朽、全知、全在、全能、全善、超然存在、人之特质、非物质性、正义以及仁慈等[102],是无法和谐并存的。

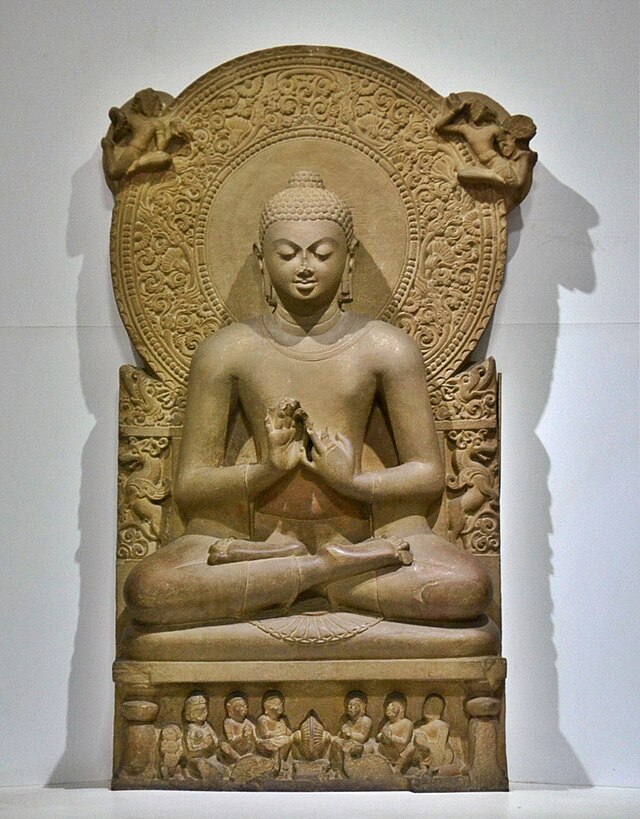

神义论无神论者认为神学家加给神的各种性质不能与现实的世界调和。他们认为全知,全能和全善的神并不能解释一个存在着罪恶痛苦以及神性隐退的世界[103]。佛教的创始人释迦牟尼也曾提出过类似的论证[104]。

价值论无神论,或称建设性无神论,因为诸如人性等“较高绝对”的存在而否定神。这种无神论论证认为人性才是道德观和价值观的绝对根源,人性也能让人无须求助于神即可解决伦理道德问题。马克思、弗洛伊德和萨特都曾使用过这种论证去传达解放、超人说以及无限制的幸福的要旨[92]。

布莱兹·帕斯卡在1669年相对于人本主义论据提出了一个至今仍然很常用的对无神论的批评[105]——那就是否认神的存在将会导致道德相对主义,使人不再有道德的基础[106],也让生命变得痛苦和无意义[107]。

信仰无神论的其他论据还包括:

- 无信仰论据:如果全能的神希望自己被所有人相信和赞美,祂们可以证明自己的存在并使所有人都相信。由于有不相信神的人存在,因此或者神不存在,或者祂们对人类不产生影响。不论哪种情况,人们都不需要相信这样的神。

历史

尽管无神论一词出现在16世纪的法国[52],但早在吠陀文化时期和古典时期就已经有无神论概念的记载了。

无神论一词源起于公元前5世纪的古希腊语ἄθεος,最初指的是对较广为接受的神灵所持有的否定态度的人[51],被神灵抛弃的人,或未承诺相信神灵的人[109]。这个由正统宗教徒所创造的词实际指代了一类社会类别,那些与他们的宗教信仰不同的人都会被归入这个类别[109]。今日语境下的无神论一词可追溯至16世纪[110]。随着自由思想和科学怀疑论的传播,以及对宗教的批评的增多,这一词语的对象范围也逐渐狭窄起来。第一个自称为“无神论者”的人出现在18世纪启蒙时代[111]。法国大革命是历史上的第一次与无神论有关的大型政治运动,其倡导人们理性至上[112]。

道家思想成形于先秦时期,直到东汉末“黄老”一词才与神仙崇拜这样的概念结合起来。部分学者认为,就本身来说,这种神仙崇拜和道家思想少有相关联成份,老子、庄子都是以相当平静的心态来对待死亡的。道家思想是哲学学派,很大程度上是无神论的[113],道教是有神论宗教信仰。引起两者相关联的原因可能是在道家的文字描述了对于领悟了“道”并体现“道”的人物意象,道教尊老子为祖师,又追求耳目不衰、长生不死,这和老子的哲学思想是有相悖之处的,将两者完全混为一谈是认识上的误区。

持道家思想的王充是中国东汉末年的思想家和文学家,他的作品《论衡》在中国思想史上具有重要地位。王充的思想被认为是无神论的[114]。他批评汉末流行的神仙崇拜、批判当时流行的天人感应,[115][116] ,认为元气是构成天地万物最原始的物质基础。他认为天并不具备情感和意义,它是一个没有主观意愿的自然实体。同时,他也认为自然现象不是上天的谴责、精神不能离开形体而独立存在[117]。哲学家冯友兰认为,王充的观点在一定程度上否定了当时流行的神秘主义和迷信观念,强调了理性思维和对自然现象的客观认识 [118]。

南北朝时期的思想家范缜对统治阶级迷信佛教、贻误国家的行为感到愤慨。他著作《神灭论》,批判宗教迷信、宣传无神论的思想。范缜认为相信精神可以脱离形体而单独存在、除了人类的世界之外还有一个独立存在的所谓"神的世界"这种观点是一种迷信、是错误的。范缜认为精神只有依附于形体才能存在,没有形体就没有精神。他强调形体是精神的载体,精神只是形体的作用而已。因此,人死后就只剩下了尸体,精神不可能独立存在。范缜指出,除了物质世界的时空之外,根本不存在非物质的、超时空的所谓"神的世界"。范缜在《神灭论》中还分析了迷信的基本手段,指出迷信制造者利用人们对鬼神的信仰,误以为灵魂可以独立存在,然后通过虚幻迷信的神话来迷惑人、吓唬人、欺骗人和引诱人。范缜强调,迷信的流行会导致社会道德败坏,使人们追求私利而忽视亲情和帮助穷人的行为。他认为,施舍应该出于真正救助他人的善意,而不是为了立即得到好报[119][120][121]。

20世纪初俄国革命的确促发了之后的一连串革命潮,中国共产党将坚持无神论的马克思主义作为中国革命的理论传入中国。中国共产党要求共产党员必须是彻底的无神论者,不仅要坚持马克思主义无神论,而且要积极宣传马克思主义无神论,普及辩证唯物主义的基本观点[122]。无神论的马克思主义是当代中国共产党的指导思想。《中国纪检监察报》的文章介绍到,按中国共产党章程来说,每一个中国共产党员必须是无神论者;公民有信仰宗教的自由,但是共产党员不能信仰宗教,不能参加宗教活动。[123]

尽管印度教是有神宗教,但它却包含无神论宗派。出现在大约公元前6世纪,坚持唯物主义和反神哲学的顺世派可能是印度哲学中最接近无神论的一派。这一哲学分支被定义成非正统派,被排除在古印度六大哲学派别之外,但因其是印度教中唯物主义运动的证据而值得注意[124]。

其他含有无神论思想的印度哲学流派包括数论派和行业派。相信有神,但对有人格的造物主概念有所排斥的,还有印度的耆那教与佛教[125]。

西方的无神论源于前苏格拉底时期的古希腊哲学,但直到启蒙时代后期才发展成明确的世界观[126]。公元前五世纪的希腊哲学家迪亚戈拉斯被称为“第一个无神论者”[127],西塞罗在他的著作《论神性》中也提到过狄雅戈拉斯[128]。克里提亚斯把宗教看成是人类的发明,其目的是恐吓其他人,好让他们接受道德规范[129]。原子论者如德谟克利特试图用纯粹的,不借助精神与神秘事物的唯物主义方式来解释世界。其他具有无神论思想的前苏格拉底时期哲学家还包括普罗狄克斯和普罗泰戈拉。公元前三世纪的希腊哲学家西奥多罗斯[128][130]与斯特拉图[131]同样不相信神的存在。

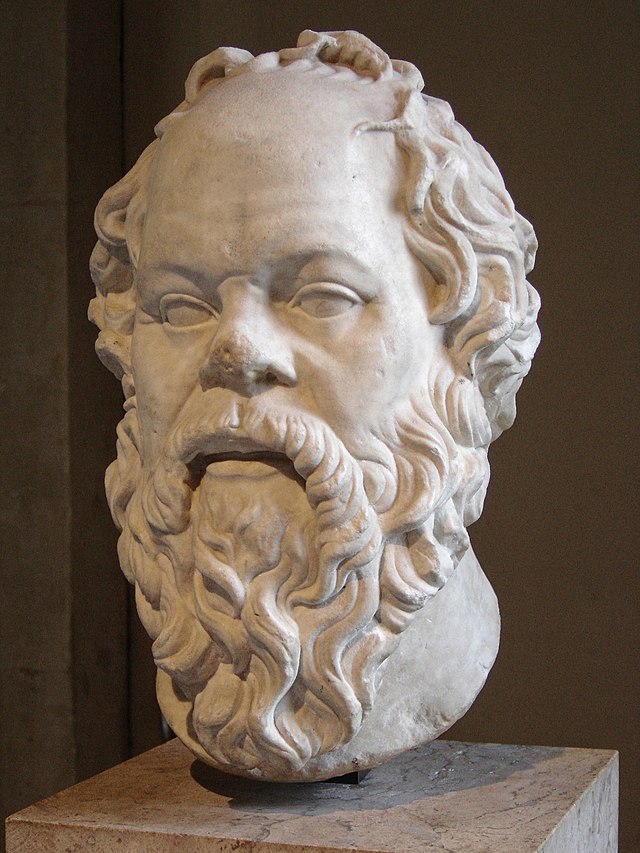

苏格拉底(约公元前471年–399年)曾因对国家神明(参见尤西弗罗困境)提出质疑而被指控为“不敬”[132]。尽管他以自己相信鬼神为由[133]否认自己是一个“纯粹的无神论者”[134],他最终仍被判处死刑。苏格拉底在与柏拉图的对话录《斐德罗》中曾向多位不同的神祈祷[135],还在《理想国》一书中说过“宙斯在上”[136]。

犹希迈罗斯(约公元前330年–260年)认为神来源于受人崇拜的古代征服者,而他们的宗教信仰在本质上其实是对那些早已消失的王国与政体的延续[137]。尽管他并不是一个严格意义上的无神论者,犹希迈罗斯仍被批评为“通过在众人居住的土地上诋毁神祇以传播无神论”[138]。

原子论唯物主义者伊壁鸠鲁(约公元前341年–270年)反对许多的宗教概念,包括来世及位格神的存在;他认为灵魂是纯粹物质的与不朽的。虽然伊壁鸠鲁主义并没有明确否认神的存在,但伊壁鸠鲁认为,如果神确实存在的话,那祂们对人类是毫不关心的[139]。

古罗马诗人卢克莱修(约公元前99年–55年)持有与伊壁鸠鲁相近的观点,即若果神存在的话,祂们不会关心人类,也不会影响自然世界。基于这个理由,他认为人类不应惧怕超自然的事物。他在著作《物性论》中阐明了自己对宇宙,自然,灵魂,宗教,道德等等事物的伊壁鸠鲁式观点[140],这本书在古罗马起到了推行伊壁鸠鲁哲学的作用[141]。

古罗马哲学家塞克斯都·恩披里柯提出了一种源于皮浪主义思想的怀疑观点,他认为人们不应该对任何一种信仰做出自己的判断,因为没有任何事物天性邪恶,而持有这种保留态度的人则能获得内心的宁静(Ataraxia)。他遗留的相对大量的著作对后世哲学家带来了持续的影响[142]。

在古典时期,“无神论者”一词的意思逐渐的发生着改变,早期的基督徒因为拒绝信奉异教神而被打上无神论者的标签[143]。到了罗马帝国时期,大批基督徒因为抵制对罗马皇帝以及罗马神祇的崇拜而被处死。而在狄奥多西一世于381年将基督教定为国教之后,基督教的异教又成为了惩罚的对象[144]。

在中世纪前期和中世纪(参见中世纪审判)的欧洲,对无神论思想的拥护是非常少见的;形而上学,宗教和神学是当时的主流[145]。但在当时仍然有一些运动在推行与基督教上帝不同的非正统观念,包括对自然的相异看法,超然存在和上帝的可知性等。一些个人和团体如约翰内斯·司各特·爱留根纳、迪南的大卫、贝纳的亚马里克以及自由灵兄弟会(Brethren of the Free Spirit)都持有一种接近泛神论的基督教思想。库萨的尼古拉则持有一种他称之为“有知识的无知”的信仰主义观点,认为上帝超出了人类的理解范畴,我们对上帝的认识都只能依靠推测。奥卡姆的威廉则产生了一种反形而上学的倾向,认为人类知识对抽象实体的认识有唯名论的限制,因此神的本质无法被人类理智所直观和理性的领会。奥卡姆的追随者,例如米尔库尔的约翰和奥特库尔的尼古拉继续扩展了这种观点。这些信仰与概念上的分歧影响了此后的一些神学家,包括约翰·威克里夫,扬·胡斯以及马丁·路德[145]。

文艺复兴运动则扩大了自由思想以及怀疑质询的范畴。一些个人如列奥纳多·达芬奇把实验看作解释事物的手段,反对宗教权威的论据。这一时期的其他宗教与教会批评家有尼可罗·马基亚维利、博纳旺蒂尔·德佩里埃和弗朗索瓦·拉伯雷[142]。

文艺复兴和宗教改革时期见证了宗教狂热的再度兴起,例如新兴教团的扩增,大众对天主教的忠诚,还有加尔文宗等新教教派的出现。这一时期的宗教间冲突也扩展了当时神学与哲学的讨论范围,为其后出现的怀疑宗教的世界观奠定了基础。

对基督教的批评在17与18世纪变得更加频繁,特别是在英国与法国,根据当时的资料,两地出现了所谓的“难以名状的宗教问题”。一些新教思想家,例如托马斯·霍布斯,支持唯物主义哲学,同时对超自然事物持怀疑态度。荷兰裔犹太哲学家巴鲁赫·斯宾诺莎反对摄理(Divine Providence)概念而支持泛神论自然主义。到了17世纪晚期,自然神论更广为知识分子所接受,如约翰·托兰德。不过,虽然自然神论者嘲笑基督教,他们对无神论也持蔑视态度。已知的第一个抛开自然神论衣钵转而强硬否认神祇存在的无神论者是一位十八世纪早期法国神父让·梅叶[146]。他的追随者包括其他更为公开的无神论思想家,例如霍尔巴赫和雅克-安德烈·奈容(Jacques-André Naigeon)[147]。哲学家大卫·休谟基于经验主义开发了一套持怀疑态度的认识论,破坏了自然神论的形而上学基础。

法国大革命把无神论从沙龙中带到了公众面前。强制执行神职人员民事组织法案的尝试导致了对大量神职人员的驱逐和暴力压制。革命时期巴黎各种混乱的政治事件最终让极端的雅各宾派在1793年获得权力,开始了恐怖统治。在恐怖高潮,一些激进的无神论者试图用武力强制的将法国去基督教化,把宗教替换为理性崇拜。这些迫害随着热月政变而结束,但这一时期的部分世俗化措施对法国政治造成了长久的影响。

拿破仑时期将法国社会的世俗化活动制度化,同时将革命带到了意大利北部,试图籍此打造容易受摆布的共和国。19世纪,许多的无神论者和反宗教思想家都投身到政治与社会活动中,促成了1848年革命、意大利统一以及国际社会主义活动的增长。

在19世纪的后半期,无神论在理性主义与自由思想哲学家的影响下变得日益彰显。这一时期的许多杰出哲学家都否认神的存在,对宗教持批评态度,他们之中有路德维希·费尔巴哈,亚瑟·叔本华,卡尔·马克思和弗里德里希·尼采[148]。

20世纪的无神论,特别是实用主义无神论,出现在了许多的社会群体中。无神论思想也为更加广域的哲学派别所认可,它们包括存在主义、客观主义、世俗人文主义、虚无主义、逻辑实证主义、马克思主义、女权主义[149]以及普通科学和理性主义。

逻辑实证主义与科学主义为随后的新实证主义、分析哲学、结构主义以及自然主义铺平了道路。新实证主义和分析哲学抛弃了古典理性主义与形而上学,转向严格的经验主义与认识论的唯名论。支持者诸如伯特兰·罗素等断然地拒绝信仰神。路德维希·维特根斯坦在他的早期工作中曾试图将形而上学与超自然的语言从理性论述中分离开来。A.J.艾耶尔断言宗教陈述具有不可证明性与无意义性,援引了自己对经验科学的坚定信仰。列维-斯特劳斯的应用结构主义否定了宗教语言的玄奥意味,认为它们都源自于人类的潜意识。J. N.芬德利和J. J. C.斯马特论证称神的存在在逻辑上是非必然的。自然主义者与唯物主义一元论者如约翰·杜威认为自然世界是万物的基础,否认了神与不朽的存在[87][150]。

20世纪同时也见证了无神论在政治上的崛起,尤其是在马克思与恩格斯理论的推动下。在1917年俄国十月革命之后,宗教自由的增加仅持续了数年,其后的斯大林主义转而压制宗教。苏联和其他社会主义国家在推动国家无神论形成的同时使用暴力手段抵制宗教[151]。

柏林墙倒塌之后,反宗教政体的数目大为减少。2006年,皮尤研究中心的蒂莫西·沙(Timothy Shah)博士指出“一股世界性的潮流已经覆盖各主要宗教团体,那就是相对于世俗运动与意识形态,基于神与信仰的运动的信心和影响力要更为明显地增长。”[152]前沿基金会的格利高里·斯科特·保罗和菲尔·查克曼(Phil Zuckerman)认为这不尽真实,实际情况较此要复杂与微妙的多[153]。近年来(2000年后)于英美等地兴起,攻击宗教信仰的无神论运动(新无神论)说明了这点,有媒体将丹尼尔·丹尼特、理查德·道金斯、山姆·哈里斯及克里斯托弗·希钦斯称作新无神论的四骑士。[154]

国家无神论

国家无神论(英语:State atheism)是一个相对于国家宗教的概念,即由政府所推行的无神论,通常会伴随着对宗教自由的压制出现[155]。大部分社会主义国家都有过这样的政策。

有关“无神论”之不同社会面向

统计无神论者人口很困难,其结果也不准确。原因主要有两个:第一,世界上一些政府推广无神论,而另一些政府压制无神论,因此对于无神论者人口的统计可能过高或过低;其次,由于无神论的定义不确定,许多统计的标准并不统一,其中一些可能仅仅统计强无神论者人口,而另一些则统计无宗教信仰的人口[157]。信仰印度教的无神论者会回答自己是印度教徒,但同时他也是无神论者[158]。无神论概念出自一神信仰的西方,该概念套用到传统东方文化上可能出现矛盾,如中国人和日本人等东方民族可能介于有神论和无神论间,与西方严格区别两个概念的思维不同。因此统计该地各国无神论者的比例,可能会出现10-90%的极大落差。特别是在日本,大多数人都同时拥有多个宗教信仰(参见日本宗教)。而无宗教信仰者并不同于无神论者,可能近似于不可知论者。

尽管无神论者在大部分国家占少数,但可以确定的是在共产主义国家(如中国、越南、古巴等)和前共产主义国家(如俄罗斯、白俄罗斯等),无神论者人数较多,这是由于共产主义国家曾经强制推行无神论。[来源请求]在西欧、澳大利亚、新西兰、加拿大等地区无神论者也较多,之后是美国,世界其他国家地区无神论者较少。[来源请求]根据1995年的调查,无宗教信仰的人口占世界总人口的14.7%,而无神论者占3.8%[159]。与此相近的,在2002年由Adherents.com网站进行的调查表明“世俗的、无宗教的、不可知论的、以及无神论的人口”比例是14%[160]。美国中情局2004年的调查表明12.5%的人没有宗教信仰,其中2.4%是无神论者[161]。根据《大英百科全书》2005年出版的调查结果,无宗教人口占世界总人口的11.9%,无神论者则占2.3%,这个统计并未包括那些信仰无神论宗教的人,例如佛教徒[162]。

2006年11至12月有调查考察美国和5个欧洲国家的无神论人口,在《金融时报》发布的调查结果显示,美国的无神论人口比例最低,只有4%;而欧洲国家的比例则较高(意大利:7%,西班牙:11%,英国:17%,德国:20%,法国:32%)[163][164]。对于美国无宗教信仰人口(包括无神论、不可知论、自然神论等)的调查结果从0.4%到15%相差较大,大约16.2%的加拿大人无宗教信仰(包括无神论者),而绝大多数墨西哥人是天主教徒(89%)。其中关于欧洲国家的数字与2005年欧盟官方调查的结果相近,根据2005年欧洲统计办公室Eurostat的统计,18%的欧盟人口不相信有神存在[42]。对于无神论者、不可知论者和其他不相信人格神的人口比例,2007年的调查显示波兰、罗马尼亚、塞浦路斯和其他一些欧洲国家无神论者所占总人口比例的数字为个位数,而在法国、英国和俄罗斯的比例更高一些,分别为40%,33%和32%[165];北欧地区的瑞典(85%)、丹麦(80%)、挪威(72%)和芬兰(60%)的比例更高。

由于在日本大多数人都同时拥有多个宗教信仰,所以很难统计无神论者的人数,但有数据称大约65%的日本人是无神论者、不可知论者或不相信神的存在[34]。中华人民共和国的执政党中国共产党的党员原则上必须是无神论者,据估计目前中国大陆有59%的人口无宗教信仰[166],香港则有14%的人有宗教信仰[167]。以色列有约20%犹太人认为自己是“世俗的”,但其中多数人由于家庭或国家的原因仍参加礼拜[168]。据2003年国际宗教自由报告所述,台湾人民大多数有宗教信仰,目前有近14%的人口不信仰任何宗教[169]。

跨国研究结果表明教育程度和不相信上帝有正相关性[43],欧盟的调查显示辍学和相信上帝有正相关性[42]。无神论在科学家中所占比例更高这一趋势在20世纪初比较明显,到20世纪末成为科学家中的多数。美国心理学家詹姆士·柳巴1914年随机调查1000位美国自然科学家,其中58%“不相信或怀疑神的存在”。同一调查在1996年重复了一次,得出60.7%的类似结果。美国科学院院士中这一比例高达93%。肯定回答不相信神的比例从52%升高至72%[170]。《自然》杂志1998年刊登的文章指出,调查显示美国国家科学院院士之中相信人格神或来世的人数处于历史低点,相信人格神的只占7%,远低于美国人口的85%比例[171]。《芝加哥大学纪事报》的文章则指出,76%的医生相信上帝,比例高于科学家的7%,但仍比一般人口的85%为低[172]。同年,麻省理工学院的弗兰克·萨洛韦和加利福尼亚大学的迈克尔·舍默进行研究显示,高学历的美国成年人(调查样本中12%持有博士学位,62%是大学毕业生)之中有64%相信上帝,而宗教信念与教育水平有负相关性[173]。门萨国际出版的杂志的文章指出,1927年至2002年之间进行的39个研究显示,对宗教的虔诚和智力有负相关性[174]。这些研究结果与牛津大学教授迈克尔·阿盖尔进行的元分析结果近似,他分析了7个研究美国学生对宗教的态度和智力商数的关系。虽然发现负相关性,该分析没有提出两者之间存在因果关系,并指出家庭环境、社会阶级等因素的影响[175]。

无神论在社会较安定的国家较为盛行,根据心理学家 Nigel Barber,由于当地医疗资源较完善,社会安全网完整,因此未来不确定性较低,无神论者较多。而在较落后的国家中,则鲜少有无神论者。[176]

无神论与宗教信仰

- 坚定地相信超自然性和上帝存在以及有关原则和理论体系

- 以热情和坚定地信念而坚持信仰的原则和理论体系

《斯坦福哲学百科全书》[178]中无神论条目中定义一章认为,有神论最好被理解为一个命题(或主张),其答案可能是“正确”或“错误”。 无神论者不相信上帝不是基于信仰,而是因为他们没有看到足够的证据来支持上帝的存在,是基于理性和证据。

山姆·哈里斯等无神论者认为西方宗教对神性权威的依靠使其联系上了威权主义与教条主义[179]。而原教旨主义与外诱性信仰(即为获得利益而信仰宗教[180])则与威权主义、教条主义以及偏见有很深的联系[181]。

英国哲学家和逻辑学家诺贝尔文学奖获得者伯特兰·罗素反对信仰[66],他认为:“基督徒认为自己的信仰行善,但其他信仰却有害。无论如何,他们对共产主义信仰也是持这种观点。我坚持的是,所有信仰都是有害的。我们可以将‘信仰’定义为对没有证据的事物的坚定信念。 在有证据的地方,没有人会说‘信仰’。我们不说‘2加2等于4’是信仰,也不说‘地球是圆的’是信仰。我们只在希望用情感代替证据时才谈到信仰。用情感代替证据容易导致冲突,这是因为不同的群体用不同的情感来代替。基督徒信仰耶稣复活,共产党人相信马克思的价值论。其中任一种信仰都不能得理性的支撑,因此,每种信仰都只得通过宣传来维持,必要时还得通过战争。”

关于无神论是否也是基于信仰,宗教和无神论双方意见不同:

- 一些批评无神论者认为无神论本身也是基于自身的信念而认为神不存在、各宗教的观点都是错的,这本身也是一种信仰[182],和各个宗教的信条没有什么区别[183]。例如《时代杂志》的专栏作家伊恩·琼斯就认为,如果站在一个世俗的角度,那么无神论者强烈否认神存在的信条似乎和基督新教相信圣经绝对无误的那些人没什么区别[184]。

- 无神论认为他们不是靠信仰,而是没有看到足够的证据来支持上帝的存在。无神论一方如伯特兰·罗素曾用罗素的茶壶认为举证神存在的责任应在有神论者身上。现代无神论者们进一步用罗素的茶壶和现代反讽性质的飞天面条神教作为一个反证法的论述,说明如果在无法由科学证明的情况要求相信和不相信一个超自然存在都得到同样的尊重和重视,那么它也必须给予相信罗素的茶壶和飞天面条神的存在同等的尊重,因为茶壶、面条神和超自然存在同样无法去由科学证明或否证[23],认为举证神存在的责任应在有神论者身上。

不过,也有一些无神论者出于传统文化等因素,依然有一些精神信仰。例如,世俗人文主义下就有犹太无神论或人文犹太教[185][186]以及基督教无神论[187][188][189]和基督徒自然神论。

佛教是否属于无神论有一定争论[190][191],甚至许多佛教人士自认为佛教是无神的[192][193]。这是因为佛教的佛与天启宗教的神有很大区别,可认为是得道的贤人。另一方面,佛教一向是承认鬼神存在的。在《华严经》、《地藏经》,乃至于《阿含经》等,都有鬼神记载。佛教认为有天神(天人)、有天帝,而这些神与一般人皆为六道众生。

伦理道德

关于是否需要靠信神和恐惧以及崇拜上帝才能维持那些与现代社会相容的伦理道德理念. 认为道德必然来自神及不能脱离一个明察善断的创造主的观点尽管在哲学上是一个老生常谈的论题,但是爱因斯坦认为:

“一个人的道德行为应该有效地建立在同情心、教育、社会联系和需求的基础上;不需要宗教基础。如果一个人不得不因害怕惩罚和希望死后得到回报而受到限制,那么他确实是一个可怜的人”

——爱因斯坦, "Religion and Science," New York Times Magazine, 1930

而柏拉图也用尤西弗罗困境中论证过神在决定事物的正确与否时所扮演的角色不是非必要的就是武断的,通常被认为是对道德需要宗教这一观点的最早反驳之一[194][195][196]。

道德戒律如“杀人有罪”一直被看作神圣法,需要一个拥有神性的立法者和法官才能成立。尽管如此,许多无神论者认为像对待法律一样对待道德本身就包含了一个错误类比,道德并不像法律那样随着制定者变化[197]。

哲学家苏珊·尼曼(Susan Neiman)[198]与朱立安·巴吉尼等人[199]认为根据神的要求而表现出道德并不是真正的道德行为,而仅仅是盲目服从。巴吉尼相信无神论是道德的优越基础,存在一个外在于宗教权威的道德基础对于评价权威本身的道德很有必要——例如一个没有宗教信仰的人也能判断出偷窃是不道德的——因而无神论者在做出这样的评价时更为有利[200]。

同时期的英国政治哲学家马丁·科恩(Martin Cohen)给出了许多圣经中的支持酷刑和奴隶的训谕的例子,作为宗教训谕是随着政治和社会发展而不是相反情况的佐证,同时指出了这一趋势对看似冷静客观的哲学发展也是适用的[201]。科恩在其著作《政治哲学:从柏拉图到毛泽东》(Political Philosophy from Plato to Mao)以《古兰经》为例详述了这一观点,他认为《古兰经》在历史上起了一个保护中世纪的社会准则不受时代变化影响的不良作用[202]。

无神论者也可以拥有从认为人类应该一致遵守同一道德准则的人文主义的道德普遍主义到认为道德无意义的道德虚无主义[203]之间任何不同的道德信仰。这一观点,连同宗教在历史上造成的破坏,如十字军东征,异端裁判所以及猎巫与宗教战争运动等等,常被反宗教无神论者用以维系自己的观点[204]。(参见: 圣经批评#伦理学批评, 对基督教的批评#伦理)

一些生物学和心理学的研究认为,道德伦理是由人类的心理生物学基础而决定的,而并非是有宗教信仰的人才能具有完整的道德伦理。有人类学的研究认为,道德源于进化,源于人类本身的生物学特性。人类是社会动物,一定程度的克己利人是人类延续的必要条件[205][206]。

英国演化生物学家道金斯认为, 我们不需要宗教就能行善。 我们的道德有达尔文式的解释:通过进化过程选择的利他基因赋予人们天然的同理心。他问道:“如果你知道上帝不存在,你会杀人、强奸或抢劫吗?” 他认为很少有人会回答“是”,这削弱了宗教在道德行为方面的必要性。为了支持这一观点,他回顾了道德的历史,认为存在一种道德时代精神,它在社会中不断演变,总体上向自由主义发展。随着它的进展,这种道德共识会影响宗教领袖如何解释他们的神圣著作。因此,道金斯指出,道德并非源于圣经,而是我们的道德进步决定了基督徒接受和否定圣经的哪些部分。[23]

FiveThirtyEight数据记者和作家Mona Chalabi 通过分析美国司法部的美国司法统计局2013年的报告[207],调查美国联邦囚犯中有宗教信仰的比例,发现监狱囚犯自称为无神论者的比例为0.1%。她同时又找出2008年美国的人口普查数据,根据2008年人口普查中有1%的无神论者,得出监狱中自认为无神论者的比例相对较低的结论。但是,她自己也在文中指出,囚犯信仰的数据中含有一个“其他”的分类,而她在比较中直接去掉了这一分类。另外,她也指出,监狱中囚犯各信仰比例与总人口中各信仰比例的不同也可能是由族裔、政经地位等因素造成,很难简单一概而论[208]。 对文章探讨的问题 “监狱中无神论者犯人的比例是低于人口中无神论者的比例吗?” Mona Chalabi综合其它问题讨论的最后回答是: 无论如何,关于监狱里的宗教信仰,你是对的: 监狱中无神论者犯人的比例是低于人口中无神论者的比例。

美国作家和无神论活动家Hemant Mehta 根据2021年美国联邦监狱局 提供的数据[209]指出,2021年无神论者仅占联邦监狱人口的 0.1%,又指出根据2021年皮尤研究中心的数据[210],自我认定的无神论者占人口的4%。 这可以得到,狱中无神论者犯人的比例是于人口中无神论者的比例40分之一。 另一方面,他指出,这一数字不能说明无神论者比有宗教信仰者更加道德,因为无神论者因为在监狱中可能处于相对的弱势地位而选择伪报自己的信仰状况,也可能是一部分并不相信有神的囚犯并不知道到底什么才是无神论。此外,这些数据也只覆盖了联邦监狱系统的囚犯,而各州监狱(美国)囚犯的数量比联邦监狱多得多。 但他认为这一数字至少表明假定无神论者都不道德这个观点站不住脚。文章中指出:

- “人们认为,如果你有宗教信仰,你永远不会做出让自己入狱的可怕事情。他们认为,做这种事的人不是真正的基督徒。但是,当新教徒约占联邦监狱人口的 23%、天主教徒占 17%、穆斯林占 8.1%(我们现在知道他们确实如此)时,就很难说所有这些人都夸大了他们的信仰。”

- 特别强调 "当在监狱里找到一名公开不信教的囚犯就像大海捞针(finding a needle in a haystack)一样时,基督教护教者和牧师就更难辩称信仰对于让人们走在正义的道路上是必要的"[211]。

- 最后的结论是,“救赎之路并不经过神。”

关于同样的数据,另外有一种解读是,因为监狱囚犯生活相对苦闷,所以也许监狱的囚犯更容易从无神论转换为信仰宗教者[212]。

基督教神学家大卫·本特利·哈特教授认为基督教与各种宗教及无神论者相同,都有暴力历史。但如果以20世纪为例,无神论者杀戮记录更多(该书第12页)[213]。对其著作Atheist Delusions的评论可见于:[214]

与大卫·本特利·哈特相反的观点如下:

- 20世纪的希特勒对600万犹太人被种族灭绝的纳粹大屠杀和斯大林清洗和屠杀等是分别以纳粹和共产主义的信仰为名义,不是以信无神论和不信上帝为名义;历史上没有以信无神论名义和不信上帝而发起的战争[215]。 许多宗教战争的原因也可能还包括国家和民族的利益,但却是以宗教名义和信仰上帝而发起的,如延续近200年几十万十字军死亡的十字军东征、包括平民有约800万人死亡的三十年战争[216]、三百万民众死于战乱及引发的饥荒和瘟疫的法国宗教战争。20世纪战争中的士兵中既有有神论者和也有无神论者,希特勒士兵中有神论者远多于无神论者,把有神论者和无神论者士兵杀戮都归于无神论者,来断言“无神论者杀戮记录更多”观点也是错误的。[217]

- 理查德·道金斯指出,斯大林的暴行并非受到无神论的影响,而是受到教条马克思主义的影响[67]。并得出结论,虽然斯大林和毛碰巧是无神论者,但他们并没有“以无神论的名义”行事[218]。道金斯称:“重要的不是希特勒和斯大林是否是无神论者,而是无神论是否有系统地影响人们做坏事。没有甚至最小的证据表明它确实如此”。[67]:309-309

1979年诺贝尔物理学奖获得者史蒂文·温伯格警示人们,无论有没有宗教,好人都会做好事,坏人都会做恶事。但是,若你想要好人做恶事,就需要宗教了[33]。比如,施行恐怖行动的宗教信徒人可能是不偷不抢的好人,但他们坚信九一一袭击事件、炸地铁等恐怖行动等按其宗教和上帝旨意是正确行动可以上天堂,所以犯下残忍的暴力恐怖罪行。但没有任何人能理性地以信无神论和不信上帝的名义,而施行911及炸地铁等恐怖行动。

参见

参考书籍

- 《上帝错觉》新无神论代表作之一。 作者理查德·道金斯是当代最著名的无神论者之一,牛津大学大众科学教育讲座教授, 英国皇家学会会员。他崇尚科学与理智并批评世界上所有的宗教都是人类制造的骗局。他在书中指出基督教《旧约》中的上帝是一个妒嫉心强、非正义、歧视同性恋、喜好杀人等等使人憎恨的恶霸。道金斯在书中批驳有神论者的各种观点,并解释美国的开国元勋们其实十分厌恶基督教。[219]

- 《上帝不伟大:宗教是如何毒害一切的》是一本2007年出版的批判宗教的非虚构类书籍,新无神论代表作之一。作者是由作家兼记者克里斯托弗·希钦斯。

- 《The God Argument: The Case against Religion and for Humanism》。

- 《无神论错觉》基督教神学家大卫·本特利·哈特教授的著作,试图反驳新无神论。

参考文献

外部链接

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.