Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ilocano people

Ethnic group From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Ilocano people (Ilocano: Tattáo nga Ilóko, Kailukuán, Kailukanuán), also referred to as Ilokáno, Ilóko, Ilúko, or Samtóy, are an Austronesian ethnolinguistic group native to the Philippines.[2] Originally from the Ilocos Region on the northwestern coast of Luzon, they have since spread throughout northern and central Luzon, particularly in the Cagayan Valley, the Cordillera Administrative Region, and the northern and western areas of Central Luzon.[3][4] The Ilocanos constitute the third-largest ethnolinguistic group in the Philippines.[5] Their native language is called Iloco or Iloko.[6]

Beyond the northern Luzon, large Ilocano populations are found in Metro Manila, Mindoro, Palawan, and Mindanao, as well as in the United States, particularly in Hawaii and California, owing to extensive Ilocano migration in the 19th and 20th centuries.[7][8] Ilocano culture reflects a blend of Roman Catholic influences and pre-colonial animist-polytheistic traditions, shaped by their agricultural lifestyle and strong family-communal ties.[9][10]

Remove ads

Etymology

Summarize

Perspective

Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Ilocanos referred to themselves as "Samtoy," a contraction of "sao mi ditoy" Ilocano words that mean "our language."[11]

The term "Ilocáno" (also spelled "Ilokáno") is the Hispanized plural form of "Ilóco" or "Ilóko," with the archaic Spanish rendering "Ylóco." It is derived from the combination of the prefix i- (meaning "of" or "from") and luék, luëk, or loóc (meaning "sea" or "bay") in the Ilocano language, translating to "from the bay." This reflects the geographical origin of the Ilocano people, whose early settlements were located near coastal regions and bays. Therefore, "Ilocano" denotes the people from the bay.[12]

An alternative etymological explanation links the term to lúku or lúkung, which refers to flatlands, valleys, or depressions in the land. This suggests that the term "Ilocano" originally denoted "people of the lowlands," referring to inhabitants of areas situated between the gúlot or gúlod (mountains) and the luék (sea or bay).[12]

The name "Ylocano" or "Ilocano" is the Hispanized version of the native term "Ilúko." It follows the grammatical structure of Spanish by appending the suffix -ano to denote a people or group, as seen in terms like Americano, Africano, and Mexicano. This adaptation signifies the race or identity of the Ilocano people according to the colonizer's linguistic conventions.

One effect of the Spanish language on the demonym is the introduction of grammatical gender. "Ilocano" or "Ilokano" typically refers to males, while "Ilocana" or "Ilokana" is used for females. However, "Ilocano" is generally considered gender-neutral and can be applied to individuals of either gender.[13]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Pre-History

The Ilocano people are one of the Austronesian peoples of Northern Luzon who migrated southward through the Philippines thousands of years ago using wooden boats known as biray or bilog for trade and cargo.[14] The prevailing theory regarding the dispersal of Austronesian peoples is the "Out of Taiwan" hypothesis, which suggests that Neolithic-era migrations from Taiwan led to the emergence of the ancestors of contemporary Austronesian populations.[15]

A genetic study conducted in 2021 revealed that Austronesians, originating from either Southern China or Taiwan, arrived in the Philippines in at least two distinct waves. The first wave occurred approximately 10,000 to 7,000 years ago, bringing the ancestors of the indigenous groups residing around the Cordillera Central mountain range. Subsequent migrations introduced additional Austronesian groups along with agricultural practices, resulting in the effective replacement of the languages of the existing populations.[16] The second wave brought the Ilocanos, who settled in the northern coastal areas of Luzon.

Early history

The early history of the Ilocanos is rooted in animistic and polytheistic religious practices, with a belief that anitos (spirits) resided in the natural environment.[9] Key deities in the Ilocano belief system included Buni, the god of the earth; Parsua, the creator; and Apo Langit, the lord of heaven. However, due to the dispersed nature of Ilocano settlements, distinct regional variations of these beliefs developed, each with its own set of deities and spiritual practices. The Ilocano religious tradition was also influenced by neighboring ethnolinguistic groups such as the Cordillerans (Igorot), Tagalogs, and external cultures, particularly the Chinese.[17][18]

Ilocanos were both agriculturalists and seafarers, engaging in active trade and barter systems with neighboring groups, including the Cordillerans, whose emporium for their gold mines and rice from their terraces in the Cordillera Central, as well as the Pangasinans, Sambals, Tagalogs, Ibanags, and foreign traders from China, Japan, and other Maritime Southeast Asian countries.[18] These interactions were part of a larger maritime trade network that spanned the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. Traded goods included porcelain, rice, silk, cotton, beeswax, gems, beads, and precious minerals, with gold being a significant commodity.[9]

Ilocano settlements were referred to as íli, a term similar to the Tagalog barangay, with smaller groups of houses known as purók. The social structure of Ilocano society was hierarchical, with leadership typically held by an agtúray or ári (chieftain), whose position was often inherited based on strength, wealth, and wisdom. The agtúray was supported by a council of elders in governance. Below the chief were the babaknáng, wealthy individuals who controlled trade and could potentially rise to leadership roles. Beneath them were the kailianes (tenant farmers or katalonan), while at the bottom of the social hierarchy were the ubíng (servants) and tagábu (slaves), who faced significant social and economic disadvantages.[19][18]

Spanish Colonization

In June 1572, the Spanish colonization of Northern Luzon commenced under the leadership of conquistador Juan de Salcedo, the grandson of Miguel López de Legazpi. Salcedo, along with an expedition of eight armed boats and 70 to 80 men, ventured northward following the successful pacification of Pangasinan.[9] The expedition encountered a cluster of native settlements collectively known as Samtoy, derived from the Ilocano phrase "sao mi ditoy" (meaning "our language here"). The Spaniards subsequently named the region Ylocos and its inhabitants Ylocanos.[18]

The Ilocanos were primarily coastal and valley settlers living in sheltered coves (luék, luëk, or loóc) along the Ilocos coastline.[12] They engaged in trade and barter with neighboring groups such as the Cordillerans (Igorots) and Pangasinenses, as well as with foreign merchants from China and Japan.[9] Despite their peaceful and self-sufficient way of life, the Ilocanos faced demands for tribute from the Spaniards, who also sought to convert them to Christianity and incorporate them into the Spanish colonial framework. These impositions provoked various forms of Ilocano resistance.[18]

One of the earliest recorded acts of defiance occurred in coastal settlement of Purao (modern-day Balaoan) literally means white in Ilocano due to pristine white beach of the area, where the Ilocanos refused to pay tribute.[9] This rebellion escalated into violence, marking the first instance of bloodshed in the Ilocanos' resistance against Spanish colonization called the Battle of Purao.[20]

Vigan Cathedral, served as the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Nueva Segovia in Northern Luzon during the Spanish colonial period.

Calle Crisologo in Vigan City, a Spanish colonial-era city.

As Salcedo's forces advanced, they subjugated numerous Ilocano settlements, including Tagurín(now Tagudin), Kaog or Dumangague (now Santa Lucia), Nalbacán (now Narvacan), Kandong (now Candon), Bantay, Sinayt (now Sinait), and Bigan (now Vigan). Among these, Vigan emerged as a vibrant trading hub frequented by Chinese merchants and a focal point of Spanish activity.[20]

Salcedo established Villa Fernandina de Vigan in honor of Prince Ferdinand, the late son of King Philip II. From this administrative center, Salcedo extended his influence to other Ilocano regions, including in the early settlements of Laoag, Currimao, and Badoc, solidifying the foundations of Spanish governance and religion in the area.[18]

By 1574, Salcedo had returned to Vigan, which had become the epicenter of Spanish administration and Christianization efforts in Ilocos. The Augustinian missionaries accompanied the Spanish forces, initiating the systematic evangelization of the Ilocano people. This period saw the establishment of religious, cultural, and administrative institutions that defined Spanish colonial rule in Ilocos.[18]

Fray Andres Carro later wrote in his 1792 manuscript, that when Juan de Salcedo conquered Ilocos in 1572,[21]

...esta provincia de Ylocos, entre dos idiomas y gentes que en ella habia tan diferentes como se vé aun hoy en esa cordillera de montes, era el idioma Samtoy ó más bien Saó mi toy, el mas general.

...this province of Ilocos, between two languages and peoples that were as different as could still be seen in this mountain range the Cordillera Range, it was the Samtoy language Ilocano language, that was the most general.

—Fray Andres Carro

According to Carro, as a result of Spanish interactions, the Spaniards learned the Ilocano language. Through its use and the increased trade and traffic among the natives an activity Carro asserts was absent prior to the Spanish arrival the Ilocano language gained prominence and became widely spoken throughout the province of Ilocos, spanning from Bangui to Agoo.[21]

Malong Revolt

In 1660, Andres Malong, a leader from Binalatongan (San Carlos), Pangasinan, initiated a rebellion against Spanish colonial rule, declaring himself "King of Pangasinan." Malong allied with Sambal and Negritos forces and sought the support of neighboring provinces of Pampanga, Cagayan and Ilocos, urging them to join his cause against the Spanish. However, the Ilocano leaders, deeply influenced by Spanish missionary and military presence, rejected Malong's demands.[22]

In retaliation, Malong dispatched Don Pedro Gumapos a Zambales chieftain with a 6,000-strong force to invade the Ilocos and Cagayan. The initial Ilocano defense, composed of 1,500 Spanish loyalists under the command of the alcalde mayor and missionaries, was defeated, allowing Gumapos' forces to sack Vigan and neighboring villages. Despite these losses, the Ilocanos organized resistance efforts. Communities in Narvacan and other areas employed guerrilla tactics, often in alliance with the Tinguians, a local indigenous group. These coordinated counterattacks inflicted significant casualties on Gumapos' forces, hindering their advance.[23]

As Gumapos' army retreated south, they burned and looted towns, including Santa Maria, San Esteban, and Candon. However, their campaign ultimately faltered upon reaching Santa Cruz, where Spanish-led forces, bolstered by Ilocano fighters, confronted them after having defeated Malong in Battle of Agoo. Gumapos' army suffered decisive defeats in two major battles, leading to his capture and subsequent execution by hanging in Vigan.[24]

The Ilocano resistance during the war was characterized by their use of guerrilla tactics, strategic alliances, and unwavering defense of their communities. Their contributions significantly weakened Gumapos' forces and played a critical role in suppressing the rebellion. The Ilocos Region's ability to repel the invasion underscored its importance in the Spanish colonial structure and marked a turning point in the conflict.

Almazan Revolt

In 1661 a significant uprising of Ilocanos led by Don Pedro Almazan of San Nicolas and Laoag, Ilocos Norte. Inspired by the earlier Malong Revolt in Pangasinan, the rebellion sought to overthrow Spanish rule and restore Ilocano self-governance. Declaring himself "King of Ilocos," Almazan used the stolen Crown of Mary from the Laoag Cathedral as a symbol of his authority, rallying widespread support from Ilocano leaders and communities.[25]

Key figures such as Don Juan Magsanop of Bangui and Don Gaspar Cristobal, the gobernadorcillo of Laoag, aligned with Almazan, forming a coalition known as the "trinity" of Ilocano leadership. Ilocano solidarity was further demonstrated through Almazan's establishment of a symbolic monarchy, including the marriage of his son to Cristobal's daughter, which became a unifying symbol for the people.[25]

Among their grievances include abuses done by government officials and friars being sent to the Philippines, which regardless of their backgrounds took higher positions than locals could ever hope to achieve. Almazan pledged to make as many shackles as there were Spanish in Ilocos when opportunity permits.[25]

On January 31, 1661, Magsanop declared independence in Bacarra and called on the Calanasanes of Apayao to join the cause. The rebels, consisting largely of Ilocano farmers, craftsmen, and local leaders, showcased their unity and resourcefulness by organizing forces, burning the church in Laoag, and advancing through Cabicungan and Pata into Cagayan. Despite their efforts, the rebels lacked reinforcements from other uprisings and faced logistical challenges.[25]

By February 1661, Spanish forces with 300 soldiers under Alférez Lorenzo Arqueros and Maestre de Campo Juan Manalo launched a counteroffensive. The Ilocano rebels employed guerrilla tactics and utilized their knowledge of the region's terrain to resist Spanish advances, forcing prolonged skirmishes in the mountainous areas. Despite their resilience and strategic efforts, the rebels were eventually overwhelmed. Juan Magsanop was captured but chose suicide over imprisonment, while Don Pedro Almazan and sixteen other leaders were captured and executed in Vigan.[25]

Silang Revolt

The first significant uprising against Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines, spearheaded by Diego Silang and, after his death, by his wife, Gabriela Silang. This revolt took place amidst the broader context of the Seven Years' War, during which Britain, retaliating against Spain's alliance with France, launched a military incursion into the Philippines. In September 1762, British forces occupied Manila, and their military operations aimed to seize control of other Philippine provinces. The weakening of Spanish power presented an opportunity for Diego Silang to lead a rebellion in Ilocos.[26]

Diego Silang's motivations were deeply rooted in the hardships experienced by the Ilocanos under Spanish rule. The Ilocanos faced heavy taxation, forced labor for the construction of churches and government buildings, and the imposition of monopolies by the Spanish. These widespread grievances contributed to a strong local support base for the revolt. Silang's disillusionment began when, while serving as a courier for the parish priest in Vigan, he witnessed the injustices faced by the people of Ilocos and the rest of the Philippines. After unsuccessful negotiations with Spanish authorities for more autonomy for the Ilocanos, he resolved to take up arms in revolt.[27]

By December 1762, Diego Silang had successfully seized Vigan and declared the independence of Ilocandia, naming it "Free Ilocos" with Vigan as its capital. He was promised military support from the British, but this assistance never materialized, leaving him vulnerable. Despite this setback, Silang pressed on with the rebellion, determined to liberate Ilocos from Spanish control. The rebellion, however, was cut short when Diego Silang was assassinated in May 1763 by Miguel Vicos, a mestizo of Spanish and Ilocano descent, who had once been his ally. The assassination was orchestrated by Spanish authorities, both governmental and ecclesiastical, in an effort to eliminate Silang's challenge to their rule. Although Diego Silang's death marked a temporary setback for the revolt, his cause was carried forward by his wife, Gabriela Silang.

Gabriela Silang assumed leadership of the insurgents and continued to resist Spanish rule. Under her command, the Ilocano forces achieved their first victory in the town of Santa, where they defeated Spanish troops. This success startled the Spanish, who had not anticipated a woman leading a revolt. After the victory, Gabriela and her forces retreated to the rugged terrain of Pidigan, Abra, where they were joined by Diego Silang's uncle, Nicolas Cariño. Cariño temporarily assumed command and gathered around 2,000 men loyal to Diego Silang.[28]

On September 10, 1763, Gabriela and her forces launched attacks on the Spanish in Vigan. While some skirmishes resulted in victories, others were defeats, and both sides suffered heavy casualties. Ultimately, Gabriela's forces were overwhelmed, and she was captured by Spanish forces led by Miguel Vicos, who had previously assassinated her husband. Gabriela was paraded through coastal towns as a public spectacle to instill fear among the Ilocanos. She was publicly hanged in September 1763, along with nearly ninety of her supporters, marking the end of the Silang Revolt. Despite her death, Gabriela Silang's legacy endured. She is often referred to as the "Joan of Arc of the Philippines" and is remembered as the first female leader in the country's history to actively fight for its liberation from colonial rule.[29]

Basi Revolt

Historical records indicate that in 1786, discontent among the populace grew due to a monopoly on local basi wine, a sugarcane-based alcoholic beverage, enforced by the Spanish colonial government. This monopoly regulated the consumption of basi and mandated that producers sell it at a low official price. Basi held significant cultural and societal importance for the Ilocanos, being integral to rituals surrounding childbirth, marriage, and death. Additionally, the production of basi was a vital industry in Ilocos, making the Spanish-imposed monopoly a substantial cultural and economic detriment.

The abuses of the Spanish authorities culminated in the Basi Revolt, also known as the Ambaristo Revolt, which erupted on September 16, 1807, in present-day Piddig, and subsequently spread throughout the province. The revolt was led by Pedro Mateo, a cabeza de barangay from Piddig, and Saralogo Ambaristo, an Ilocano and Tinguian. Participants included disgruntled elements from various towns of Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur, including Piddig, Badoc, Sarrat, Laoag, Sinait, Cabugao, Magsingal, and others. They marched southward under their own flag of yellow and red horizontal bands toward the provincial capital of Vigan to protest the abuses of the Spanish colonial government.

In response to the revolt, the alcalde-mayor, Juan Ybañez, mobilized the town mayors and the Vigan troops to confront the rebels. On September 28, while crossing the Bantaoay River in San Ildefonso en route to Vigan, the Ilocano forces were ambushed by Spanish troops, resulting in the deaths of hundreds. Survivors faced execution, and their leaders were publicly rounded up and executed, serving as a stark warning against further resistance.

The Basi Revolt lasted for 13 days, prompting the colonial government to partition the Ilocos province into Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur. Although the revolt did not achieve its primary objective of liberation, it succeeded in galvanizing subsequent movements for justice and freedom in Northern Luzon. The division of the Ilocos Province into two distinct regions was a direct consequence of the unrest, highlighting the colonial government's efforts to manage and suppress the growing discontent among the Ilocano people. Ultimately, the Basi Revolt marked a significant chapter in the struggle against Spanish colonial rule, laying the groundwork for future movements advocating for justice and autonomy.[30]

Philippine Revolution

The Ilocano revolutionaries made significant contributions to the Philippine Revolution, employing Ilocano fighting techniques and weapon styles, particularly through their leadership and military efforts under General Manuel Tinio, a central figure in the northern resistance against Spanish forces. His brigade garrisoned the entire western portion of Northern Luzon, which included Pangasinan and the four main Ilocano provinces: Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, Abra, and La Union, as well as the comandancias of Amburayan, Lepanto-Bontoc, and Benguet. To manage this vast territory effectively, General Tinio divided it into three military zones:

- Zone 1, under Lt. Col. Casimiro Tinio, covered La Union, Benguet, and Amburayan.

- Zone 2, led by Lt. Col. Blas Villamor, encompassed Southern Ilocos Sur (from Tagudin to Bantay), Abra, and Lepanto-Bontoc.

- Zone 3, commanded by Lt. Col. Irineo de Guzman, included Northern Ilocos Sur (from Sto. Domingo to Sinait) and Ilocos Norte.

The Villamor brothers, Blas and Juan, played crucial roles in leading the Ilocano resistance, particularly in Abra, where their guerrilla warfare tactics against Spanish forces were vital in securing key areas. Estanislao Reyes of Vigan, Ilocos Sur, was another significant leader who helped organize and defend against Spanish control in the region.[31] Tinio and his generals resorted to guerrilla warfare to outmaneuver Spanish troops, utilizing the challenging terrain of northern Luzon to their advantage. The military campaigns were highly effective, especially in the Ilocos Sur area, where Blas Villamor defended towns such as Tagudin and Bantay. Juan Villamor focused on strategic operations in Abra, helping to weaken Spanish influence in the region.

In August 1898, the Ilocanos drove the Spanish forces out of several towns, including Laoag, Ilocos Norte, a significant victory that marked a turning point in the revolution. This enabled the revolutionaries to continue their push south and establish provisional governments aligned with Emilio Aguinaldo's revolutionary government.

Meanwhile, Father Gregorio Aglipay, the military vicar general of the Philippine Revolutionary Army, led a separate campaign in Ilocos Norte. Father Aglipay, who would later found the Philippine Independent Church, played a key role in rallying local support and organizing military operations in the region. His leadership was not only religious but also military, as he led several attacks on Spanish forces, contributing to the weakening of Spanish control in Ilocos Norte.

The Cry of Candon is recognized as one of the earliest uprisings that occurred during the second phase of the Philippine Revolution. On March 25, 1898, a force of Ilocano Katipuneros, led by Don Isabelo Abaya, launched an assault on the town of Candon and successfully captured the convent and the center of town from Spanish forces.[32]

The Battle of Vigan, fought in August 1898, stands as one of the most important Ilocano-led victories. Under Estanislao Reyes, the Ilocano fighters successfully defended the town of Vigan, Ilocos Sur, against the Spanish. This battle was crucial in demonstrating the Ilocano people's determination to resist foreign control.[33]

In 1899, as the Philippine-American War intensified, the Ilocano revolutionaries, led by Tinio and his generals, continued to rely on guerrilla tactics to resist American forces. The Ilocanos, familiar with the mountainous terrain, conducted surprise attacks and ambushes, making it difficult for American forces to maintain control over the region.

By 1901, the region eventually fell under American control after prolonged resistance. However, the Ilocano revolutionaries, under the leadership of General Tinio, the Villamor brothers, and Estanislao Reyes, delayed American forces for months, buying valuable time for the rest of the nation's revolutionary efforts. Ilocano resistance ended in April 1901.

Philippine-American War

The Ilocano resistance during the Philippine-American War (1899–1901) was a period marked by intense conflict and defiance against American occupation in Northern Luzon. The war with the Ilocanos commenced in late November 1899, when General Samuel Baldwin Marks Young led an American offensive through La Union and Ilocos Sur, pushing back the forces of General Manuel Tinio. In response, Ilocano revolutionaries engaged in a combination of guerrilla warfare and conventional battles.[34]

In November 1899, Young's forces captured key Ilocano towns, including San Fernando, Agoo, Balaoan, and Bangar, forcing Tinio's troops to retreat northward. Significant battles occurred in major towns such as Vigan, Laoag, Candon, Bangued, and Santa Maria, where Ilocano forces launched daring attacks on American garrisons.[34]

On December 2, 1899, the Battle of Tirad Pass became a defining moment in the resistance, as General Gregorio del Pilar and his men fought to delay American forces pursuing President Emilio Aguinaldo.[13][34]

Throughout 1900, Ilocano forces maintained strong resistance, engaging in battles and skirmishes in Narvacan, Batac, Piddig, San Nicolas, Sinait, and Santa Cruz. Guerrilla fighters disrupted American supply lines and launched ambushes in Tangadan Pass, Bangui, Badoc, and Pasuquin, targeting American patrols and military convoys. Prominent figures such as Colonels Joaquin Luna, Blas and Juan Villamor, Major Estanislao Reyes, Gregorio Aglipay and La Union governor Lucino Almieda and Ilocos Norte governor Ireneo Javier played pivotal roles in the conflict.[34]

In January 1900, coordinated attacks in Namacpacan (now Luna), Santo Domingo, Lapog (now San Juan), and Cabugao included cutting telegraph lines and raiding American garrisons. Major confrontations also occurred in Piddig, Laoag, and Candon, where Filipino forces continued to resist despite increasing American military pressure.[34]

Ilocano civilians were instrumental in sustaining the resistance by providing food, intelligence, and logistical support. Towns and villages served as supply points for guerrilla fighters, despite the threat of American retaliation.[34] The region's harsh terrain, including mountains and forests, was effectively utilized to evade American pursuit and launch surprise attacks.

Religious leaders, particularly Gregorio Aglipay, supported the revolution by rallying local communities and maintaining morale among the fighters. Women, such as Eleuteria Florentino and Salome Reyes, were arrested and deported for their support of the resistance, illustrating widespread civilian involvement.[34]

The American response to the Ilocano resistance was severe, involving brutal counterinsurgency measures such as village burnings, mass arrests, and the forced relocation of civilians to garrisoned town centers. General Samuel Young, a key figure in the American pacification campaign, led numerous operations against Ilocano strongholds and implemented harsh policies to suppress the resistance.[34]

Later, General J. Franklin Bell adopted a strategy of concentrating civilians in town centers to cut off resources to the guerrillas. American forces also enlisted Igorot tribesmen, who captured Filipino fighters in exchange for rewards. Despite these aggressive tactics, Ilocano forces continued to resist, engaging in battles such as the skirmishes in Parparia and Mount Simminublan, where they inflicted significant casualties on American troops.[34]

By 1901, the resistance began to wane as American counterinsurgency efforts intensified. The capture or surrender of key leaders, including Colonel Blas Villamor, Major Estanislao Reyes, and Colonel Joaquin Alejandrino, weakened the movement's operational capacity.

On April 29, 1901, General Tinio formally surrendered in Vigan, followed by the surrender of his remaining 350 men in May 1901, effectively marking the end of the Ilocano resistance. Despite their eventual defeat, the tactical ingenuity and resilience of the Ilocano revolutionaries played a crucial role in the broader struggle for Philippine independence, leaving a lasting legacy of defiance against colonial rule.[34]

American Colonization

By 1901, the US had fully established control over Ilocandia, implementing a military government to suppress local resistance and manage growing insurgencies among the Ilocano population. This military rule was eventually replaced by a civil government, marking a significant shift in the region's governance. Under the civil administration, Ilocano society began to transition into a more organized and democratic structure, influenced by American political and social models.[20]

Key priorities included the expansion of education, suffrage, civil rights, and political participation, which empowered the Ilocano people to actively engage in the democratic processes introduced by the Americans. However, tensions persisted as U.S. military officials, including Colonel William Duvall, resisted relinquishing their control, resulting in frequent conflicts with the Philippine Commission, led by Civil Governor William Howard Taft.

One of the most significant initiatives of the American colonial government was the establishment of public schools, spanning Ilocano provinces such as Abra, La Union, Pangasinan, Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, and Cagayan. A group of American teachers known as the Thomasites were tasked with promoting "Americanization" through education. English became the primary medium of instruction, and students were taught American ideals and values. A notable product of this educational initiative was Camilo Osias, an Ilocano student from Balaoan, who later pursued further studies in the United States and became a prominent educator and public servant.[35]

Public health also saw significant improvements during American rule. To combat widespread diseases such as cholera, the U.S. introduced public health initiatives, establishing hospitals and other medical services across Ilocandia. These efforts contributed to the overall improvement of the population's health and well-being.

Ilocano Migration

The American colonial period also marked a significant chapter in the larger history of Filipino migration. In 1906, the first group of Ilocano migrants, known as the "Sakadas," were recruited by Albert F. Judd of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) to work on sugarcane plantations in Hawaii. This migration wave continued until 1919 and was a defining moment in the history of Ilocano emigration.[14][7]

Between 1906 and 1930, over 30,000 Ilocanos migrated to Hawaii and California in search of better economic opportunities, particularly in agricultural work. The Ilocano community played a central role in shaping the Filipino workforce in Hawaii and the broader U.S. agricultural economy. As a result, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 85% of the Filipinos in Hawaii are Ilocano and the largest Asian ancestry group in Hawaii.[23]

World War II

In 1901, the region came under American colonial rule, and in 1941, under Japanese occupation.

During the Second World War, in 1945, the combined American and Philippine Commonwealth troops, including the Ilocano and Pangasinan guerrillas, liberated the Ilocos Region from Japanese forces.[citation needed]

Modern history

Post-independence period

Three modern presidents of the Republic of the Philippines hailed from the Ilocos Region: Elpidio Quirino, Ferdinand Marcos, and Fidel Ramos. Marcos expanded the original Ilocos Region by transferring the province of Pangasinan from Region III into Region I in 1973, and imposed a migration policy for Ilocanos into Pangasinan.[36] He also expanded Ilocano influence among the ethnic peoples of the Cordilleras by including Abra, Mountain Province, and Benguet in the Ilocos region in 1973,[37] although these were later integrated into the Cordillera Administrative Region in 1987. A third "Ilocano" President, Fidel V. Ramos, hailed from Pangasinan.[citation needed]

Martial Law era

Ilocanos were also among the victims of human rights violations during the martial law era which began in September 1972, despite public perception that the region was supportive of Marcos' administration.[38] According to the Solidarity of Peasants Against Exploitation (STOP-Exploitation), various farmers from the Ilocos Norte towns of Vintar, Dumalneg, Solsona, Marcos, and Piddig were documented to have been tortured,[38] and eight farmers in Bangui and three indigenous community members in Vintar were forcibly disappeared (euphemistically, "salvaged") in 1984.[38]

Ilocanos who were critical of Marcos' authoritarian rule included Roman Catholic Archbishop and Agoo native Antonio L. Mabutas, who spoke actively against the torture and killings of church workers.[39][40] Another prominent opponent of the martial law regime was human rights advocate and Bombo Radyo Laoag program host David Bueno, who worked with the Free Legal Assistance Group in Ilocos Norte during the later part of the Marcos administration and the early part of the succeeding Corazon Aquino administration. Bueno was assassinated by motorcycle-riding men in fatigue uniforms on October 22, 1987 – part of a wave of assassinations which coincided with the 1986–87 coup d'état which tried to unseat the democratic government set up after the 1986 People Power Revolution.[41][42]

Others critics included student activists Romulo and Armando Palabay of San Fernando, La Union, who were tortured and killed in a Philippine military camp in Pampanga;[43] and Purificacion Pedro, a Catholic lay social worker who tried to help the indigenous peoples in the resistance against the Chico River Dam Project, but was caught in the crossfire of a military operation, and was later murdered in the hospital by a soldier who claimed she was a rebel sympathizer.[44]

Bueno, Pedro, and the Palabay brothers would later be honored as martyrs of the fight against the dictatorship at the Philippines' Bantayog ng mga Bayani memorial.[42][43][44]

Remove ads

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority's 2020 report on Ethnicity in the Philippines, the Ilocano people represent the third largest ethnolinguistic group in the country, totaling 8,746,169 individuals, which constitutes 8.0% of the national population. They follow the Tagalog and Bisayan groups in size. While Ilocanos have dispersed widely both within the Philippines and abroad, the highest concentration of Ilocano people remains in their home provinces, where they number approximately three million. Specifically, they account for 58.3% or 3,083,391 of the population in the Ilocos Region, with Pangasinan hosting the largest number at 1,258,746, followed by La Union with 673,312, Ilocos Sur with 580,484, and Ilocos Norte with 570,849.[5]

In Northern Luzon, particularly in neighboring provinces where Ilocanos have migrated, they have also become the predominant ethnic group. In Region II (Cagayan Valley), there are 2,274,435 Ilocanos, representing 61.8% of the region's population. In Isabela, 1,074,212 Ilocanos were recorded, followed by Cagayan with 820,546, Nueva Vizcaya with 261,901, Quirino with 117,360, and Batanes with 416. The Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) recorded a total of 396,713 Ilocanos, making up 22.1% of its population. Abra had the highest number with 145,492, followed by Benguet (including Baguio City) with 138,022, Apayao with 47,547, Kalinga with 31,812, Ifugao with 26,677, and Mt. Province with 7,163 Ilocanos.[5]

Beyond Northern Luzon, in Region III (Central Luzon), Ilocanos comprise 10.8% or 1,335,283 of the region's population, making them the third most common ethnic group there. Tarlac registered 555,000 Ilocanos, followed by Nueva Ecija with 369,864, Zambales (including Olongapo City) with 183,629, Bulacan with 97,603, Aurora with 65,204, Pampanga (including Angeles City) with 40,862, and Bataan with 29,121. In the National Capital Region (NCR), 762,629 Ilocanos were recorded. The highest number was in Quezon City with 213,602, followed by Manila City with 112,016, Caloocan City with 97,212, Taguig City with 54,668, Makati City with 44,733, Valenzuela City with 36,774, and Pasig City with 35,671 Ilocanos.

In Southern Luzon, specifically in Region IV-A (CALABARZON), there were 330,774 Ilocanos, with the majority residing in Rizal (141,134) and Cavite (126,349), followed by Laguna with 44,173, Batangas with 10,402, and Quezon (including Lucena City) with 8,716. Region IV-B (MIMAROPA) had 117,635 Ilocanos, with Occidental Mindoro hosting 53,851 and Palawan 33,573. In the Bicol Region (Region V), there were 15,434 Ilocanos, the majority of whom lived in Camarines Sur (5,826) and Albay (3,236).

In the Visayas, Region VI (Western Visayas) recorded 3,952 Ilocanos, the majority residing in Aklan (1,061). In Region VII (Central Visayas), there were 4,330 Ilocanos, with the largest number in Bohol (1,651). In Region VIII (Eastern Visayas), 4,797 Ilocanos were recorded, with Leyte hosting the majority (1,840).

In Mindanao, Region IX (Zamboanga Peninsula) had 20,232 Ilocanos, with the largest population in Zamboanga del Sur (7,996). In Region X (Northern Mindanao), there were 30,845 Ilocanos, most of whom lived in Bukidnon (23,957). Region XI (Davao Region) recorded 75,907 Ilocanos, with Davao del Norte hosting the largest population (31,333). In Region XII (SOCCSKSARGEN), 248,033 Ilocanos were recorded, with the majority in Sultan Kudarat (97,983). Region XIII (CARAGA) had 24,211 Ilocanos, most of whom resided in Agusan del Sur (13,588). Finally, in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), there were 17,568 Ilocanos, with the majority in Maguindanao del Norte (including Cotabato City) and Maguindanao del Sur, where 11,262 Ilocanos were recorded.[5]

Diaspora

The Ilocano diaspora is a complex blend of both forced and voluntary migration. It represents the broader narrative of "leaving the homeland" driven by economic necessity, social upheaval, and the quest for better opportunities. Ilocanos, primarily from the Ilocos Region in the Philippines, have historically migrated to escape oppressive conditions imposed by Spanish colonizers and to seek new opportunities.

Ilocano diaspora dates back to the 19th century when Ilocanos began migrating to various parts of the country to seek employment and cultivate land. As early as 1903, they moved and settled in nearby provinces in Luzon. A study conducted on the diaspora of Ilocanos in Cagayan stated, "the reasons for Ilocano migration can be associated with economic factors which have deeper roots in the forced labor imposed by Spanish colonizers and the climatic conditions in the region that make growing crops difficult". This initial wave of migration was spurred by mounting population pressures and high density during the mid-19th century, causing many Ilocanos to leave their traditional homeland.[4]

By 1903, over 290,000 Ilocanos had migrated to regions such as Central Luzon, Cagayan Valley, and Metro Manila. More than 180,000 relocated to the provinces of Pangasinan, Tarlac, and Nueva Ecija. There has historically been a sizable Ilocano population in Aurora and Quezon province, dating back to when these areas were part of Southern Tagalog and one whole province.[45][46][47] Almost 50,000 Ilocanos moved to Cagayan Valley, with half of them residing in Isabela. Other provinces that attracted Ilocano migrants included Zambales, which housed around 47,000 migrants, and Sultan Kudarat, where more than 11,000 settled.

In subsequent years, further migrations brought Ilocanos to the Cordilleras, Mindoro, and Palawan. Between 1948 and 1960, around 15% of Ilocano migrants moved to Mindanao,[48] establishing communities in provinces such as Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, South Cotabato, Bukidnon, Misamis Oriental, Caraga, and the Davao Region. Notably, Ilocanos even form a minority in Cebu City, where they organized associations for Ilocano residents and their descendants.[49]

The Ilocano diaspora extended beyond the Philippines when, in 1906, many Ilocanos began migrating to the United States. This migration primarily aimed at finding work in agricultural plantations in Hawaii and California. The first wave of Filipino migrants to the United States consisted of the manongs and sakadas. In Ilocano, the term manong is loosely used to refer to an elderly gentleman, originally meaning "older brother," derived from the Spanish term hermano, which translates to "brother" or "sibling."[50] Meanwhile, sakadas roughly translates to "imported ones," "lower-paid workers recruited out of the area," or "migrant workers," and denotes manual agricultural laborers who work outside their provinces.

During the early 20th century, the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association recruited Filipino men to work as skilled laborers in the sugarcane and pineapple fields of Hawaii. Most of these men hailed from the Ilocos region, motivated by the hope of gasat, or "fate" in Ilocano. In April 1906, the Association approved a plan to recruit labor from the Philippines and tasked Albert F. Judd with the recruitment effort. The first Filipino farm laborers in Hawaii arrived in December 1906, specifically from Candon, Ilocos Sur, aboard the SS Doric (1883).[8] About 200 Ilocano sugar plantation workers arrived in Hawaii in 1906 and 1907. By 1929, Ilocano immigrants to Hawaii had reached 71,594. Most of the 175,000 Filipinos who went to Hawaii between 1906 and 1935 were single Ilocano men.[7][51]

The Ilocano community in the United States has continued to grow, making them one of the largest groups of Filipino expatriates in the country. Many are bilingual, speaking both Ilocano and Tagalog. In Hawaii, Ilocanos constitute more than 85% of the Filipino population, maintaining their cultural identity while also integrating into the broader American society.[52]

Today, Ilocanos can be found all over the world as migrants or Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), contributing to various sectors and economies in countries across the globe.[53]

Remove ads

Languages

Summarize

Perspective

The native language of the Ilocanos is Iloco or Iloko with 8.7 million native speaker and about 2 million as second language, classified under its own branch within the Northern Philippine subgroup of the Austronesian language family.[54] Closely related to other Austronesian languages in Northern Luzon, it exhibits slight mutual intelligibility with the Balangao language and the eastern dialects of the Bontoc language.

Ilocano has no official dialectology . A general accepted one is the Amianan (North) and Abagatan distinction, however they have no official basis other than the sound of schwa /ə/. Other distinctions like the so-called "Cordilleran" dialect (mainly talking about Baguio-Benguet) have no formal studies as of now. In 2012, it was declared the official language of the province of La Union.[55]

Ilocanos are predominantly trilingual, with Iloco as their first language and Filipino (Tagalog) and English as their second languages. Due to migration and interactions with other ethnolinguistic groups, some Ilocanos have also become multilingual, acquiring proficiency in various regional languages.

In Pangasinan, some Ilocanos can understand or speak Pangasinan and Bolinao. In the Cagayan Valley, Ilocanos may have varying degrees of familiarity with Ibanag, Itawis, Ivatan, Gaddang, Yogad, Isinai, and Bugkalot. In Central Luzon, particularly in the provinces of Zambales and Tarlac, Ilocanos may also have knowledge of Sambal and Kapampangan.[56][57][47][58][59]

In the Cordillera Administrative Region, Iloco serves as a lingua franca among different Cordilleran (Igorot) ethnolinguistic groups where it is spoken as a secondary language by over two million people. Some Ilocanos in Abra speak Itneg, while those in Benguet and Baguio may know Kankanaey and Ibaloi. In Apayao and Kalinga, they may also speak Isnag and Kalinga languages.

In Hawaii, 17% of those who speak a non-English language at home speak Iloco, making it the most spoken non-English language in the state.[60]

Ilocanos who have migrated to Mindanao, particularly in the Soccsksargen and Caraga region, often adopt Hiligaynon, Cebuano, or other indigenous languages, such as Butuanon and Surigaonon, due to cultural integration with local ethnic groups. Over time, many Ilocanos in Mindanao have assimilated into the Cebuano-speaking majority (Hiligaynon-speaking in case of Soccsksargen), often identifying as Visayans.[61]

While some retain Ilocano as a second or third language, younger generations in Mindanao primarily speak Cebuano or Hiligaynon, with limited knowledge of Ilocano. In Zamboanga City and Basilan, Ilocanos and their descendants commonly speak Chavacano, reflecting the region's distinct linguistic landscape and cultural diversity.[62]

The pre-colonial writing system of the Ilocano people, known as kur-itan or kurdita,[2] has garnered interest in recent years, with proposals to revive the script through educational initiatives in Ilocano-majority areas such as Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur.[63]

Remove ads

Religion

Summarize

Perspective

The religious landscape of the Ilocano people is largely shaped by Roman Catholicism, a lasting influence of Spanish colonization, which began in the mid-16th century. This introduction of Christianity deeply impacted the spiritual customs and beliefs of the Ilocanos. However, indigenous traditions and practices continue to persist. This fusion of faiths has created a distinct religious identity, reflecting both the historical impact of colonization and the resilient spirit of Ilocano culture. Today, Ilocano religious identity continues to evolve, influenced by both traditional customs and modern developments, while remaining closely connected to their cultural heritage.[64][65][66]

Christianity

Roman Catholicism

When the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines in the 1500s, they introduced Roman Catholicism, which quickly became the dominant religion among Ilocanos. Spanish missionaries, particularly the Augustinian friars, played a pivotal role in converting the local population to Christianity. This conversion significantly reshaped the spiritual and cultural landscape of Ilocano society, and today, Catholicism remains central to their way of life, influencing everything from personal faith to communal activities.[67]

One of the most prominent expressions of Catholicism in Ilocano culture is through religious festivals, or fiestas. These celebrations are held in honor of a town or barangay's (village) patron saint. Each community has its own patron, and the fiesta is a time of thanksgiving, celebration, and social gathering. The fiestas are marked by processions, masses, and street parades where religious images are carried through the streets, accompanied by music, dance, and feasting. These celebrations serve as a fusion of religious devotion and cultural identity, bringing together families and communities in shared faith and festivities. Some well-known fiestas in the Ilocos region include the Paoay Church Fiesta in honor of Saint Augustine and various celebrations dedicated to the Virgin Mary.[68]

procession]]

The Ilocano people also observe major Christian celebrations with great reverence. One of the most significant is Semána Santa or Nasantuan a Lawas (Holy Week), which commemorates the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. During this time, Ilocanos participate in various rituals, including processions and reenactments of the Stations of the Cross. One traditional practice is the carroza, pabása or novena, where the Passion of Christ is chanted or recited in a communal gathering.[69][70] The leccio is a form of lamentation expressed by Mary, the mother of Jesus, reflecting on the suffering and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. This lament is comparable to the dung-aw, a traditional Ilokano mourning ritual typically performed by elder women.[71]

Todos los Santos (All Saints' Day) and Pista Natay or Aldaw Dagiti Kararua (All Souls' Day) are also significant, observed every November 1 and 2. These days are dedicated to honoring the saints and remembering deceased loved ones. Families visit cemeteries to offer prayers, flowers, and food (atang) at the graves of their relatives, demonstrating the Catholic tradition of reverence for the souls of the departed.[72]

The Christmas season, or Paskua, is another highly anticipated time for Ilocanos. The celebration begins with the Misa de Gallo or Simbang Gabi, a series of nine dawn masses leading up to Christmas Day. This tradition is deeply rooted in Ilocano Catholic life, where families wake up early to attend these masses in preparation for the birth of Christ. Christmas in Ilocano communities is also marked by feasts, the exchange of gifts, and the display of parols (traditional star-shaped lanterns) that symbolize the star of Bethlehem.[73]

Other Denominations

While Roman Catholicism remains the dominant faith among the Ilocano people, other religious groups have made significant inroads, particularly the Philippine Independent Church, commonly known as the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (Aglipayan Church).[74] Founded in 1902 by Father Gregorio Aglipay from Ilocos Norte, this church emerged as a nationalist response to Spanish colonial control over the Catholic Church in the Philippines. Its establishment was rooted in the desire for a church that reflected Filipino identity and sovereignty, free from foreign influence. Although the Aglipayan Church shares many rituals and practices with Roman Catholicism, it distinguishes itself through its emphasis on nationalism, appealing to those who resonate with the country's struggle for independence.[75]

In addition to the Aglipayan Church, various Protestant denominations have been introduced to the Ilocano community, largely through American missionaries during the colonial period. Denominations such as the United Church of Christ in the Philippines and Iglesia ni Cristo have established congregations throughout the region, offering alternatives to the predominant Catholic faith. These Protestant churches focus on fostering personal relationships with God, upholding the authority of the Bible, and engaging in active community service, which has resonated with many Ilocanos seeking a different expression of their faith.[citation needed]

Indigenous belief

The early Ilocano people held animistic beliefs with Angalo a giant and the first man, and son of the god of building.[76] Their world was populated by deities and spiritual beings who controlled everything from the weather to the harvest, and who required respect, offerings, and rituals in exchange for their favor and protection. These indigenous beliefs evolved over time, influenced by the Ilocano people's interactions with neighboring cultures and through trade with other civilizations, such as the Igorot, Chinese and Tagalog communities.[77]

Deities

In Teodoro A. Llamzon's Handbook of Philippine Language Groups (1978), the Ilocano belief system is described as having several key deities who governed the natural world. Among them was Buni, the supreme god, and Parsua, the creator. Other significant deities included Apo Langit, the lord of the heavens; Apo Angin, the god of the wind; Apo Init, the god of the sun; and Apo Tudo, the god of rain. These gods were believed to be ever-present, shaping the daily lives of the Ilocano people through the natural forces they controlled.[78]

However, due to the geographic distribution of Ilocano settlements, variations in their religious practices emerged. Each region developed its own distinct versions of the Ilocano deities, often blending indigenous beliefs with those of neighboring ethnic groups like the Igorot, Tagalog, and Chinese traders. For instance, a myth from Vigan, Ilocos Sur, recorded in 1952, features an entirely different set of deities. In this myth, Abra, the god of weather, fathered Caburayan, the goddess of healing, while other gods like Anianihan (god of harvests), Saguday (god of the wind), and Revenador (god of thunder and lightning) play prominent roles. This shows how the Ilocano cosmology was shaped by both internal diversity and external cultural influences.[78]

The influence of trade is evident in some of these myths. The presence of Maria Makiling, a figure also found in Tagalog myths, suggests that the Ilocano mythology absorbed elements from neighboring Tagalog regions, while other symbols, like the use of "lobo" (Spanish for wolf) in the mythological pantheon, show the influence of Spanish colonization. Vigan, a bustling trade hub long before the Spanish arrived, saw extensive interactions with Chinese merchants, whose myths and stories likely influenced Ilocano lore. In fact, some scholars suggest that Ilocano epics, like the famous tale of Lam-ang, bear traces of Hindu and Southeast Asian mythology, a reflection of the Majapahit Empire's influence on precolonial trade routes.[78]

Spirits

At the heart of Ilocano religion was the belief in anito—spirits that governed all aspects of the natural and spiritual worlds. These spirits could be benevolent or malevolent, depending on how they were treated by the living. Specific spirits governed different aspects of the environment, such as the litao, spirits of the waters, the kaibáan, spirits of the forest undergrowth, and the mangmangkik, spirits of trees. The Ilocano people believed that cutting down trees or disposing of hot water without proper appeasement of these spirits could result in illness or misfortune.[19]

To avoid angering these spirits, the Ilocanos performed rituals, including chanting specific incantations. For example, before cutting down a tree, they would recite a chant that called upon the mangmangkik, asking for forgiveness and protection. Similar practices were performed for the kaibáan and other spirits, showing a deep respect for the natural world. To appease the mangmangkik before cutting down a tree, the following chant was made:

Bari Bari.

Dikat agunget pari.

Ta pumukan kami.

Iti pabakirda kadakami.

Offerings, called atang, were another key aspect of Ilocano spiritual life. These offerings, which included food, were placed on platforms called simbaan or in caves where spirits were believed to dwell. The atang served as a form of tribute to ensure that the spirits remained peaceful and benevolent toward the living.[79]

Cosmology

Ilocano cosmology is centered around the concepts of suróng (upstream, symbolizing creation and life) and puyupoyán (downstream, representing death and the afterlife), which shaped their understanding of the universe. Offerings to the dead were often floated downstream to symbolize the soul's journey to the afterlife. The Milky Way, known as ariwanás or Rimmuok dagiti Bitbituén, was viewed as a celestial river, reinforcing the Ilocano connection between water and the cosmos.[80]

A creation myth describes Aran, who created the sky and hung the sun, moon, and stars, and his companion Angalo, who shaped the land and, through spitting on the ground, brought forth the first humans. These humans, carried in a bamboo tube, washed ashore in the Ilocos region, establishing a link between the Ilocano people and their divine ancestors.[80]

The Ilocanos also associate shooting stars, known as layáp, with love, believing they carry mystical babató (miraculous stones of love) that can be captured by tying a knot in a handkerchief when one falls. One tale recounts lovers who mysteriously drowned in a shallow marsh. Furthermore, the goddess Sehal, meaning beauty, may have been an Ilocano counterpart to Venus, invoked in love letters and symbolizing a deep reverence for love and beauty.[81]

Soul and afterlife

The Ilocano people believed in a multi-soul system, with four distinct types of souls, each serving different functions. The kararúa was the equivalent of the Christian soul, which left the body only upon death. The karkarma could leave the body during moments of extreme fear or trauma, while the aniwaas wandered during sleep, visiting familiar places. The araria was the soul of the dead, which could return to the world of the living, often manifesting as a poltergeist or through omens like the howling of dogs or the breaking of glass.[82]

Ilocanos held elaborate death rites, believing that the souls of the deceased required offerings during their transition to the afterlife. These offerings included food and money to help the soul pay the toll to the agrakrakit, the spirit who ferried souls across rivers to the afterlife. This belief in the river as a pathway to the afterlife reflects a larger theme in Ilocano religion: water as both a source of life and a passageway to death.[79]

Water beliefs

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Water played an essential role in Ilocano spirituality, with Apo Litao, the god of the sea and rivers, being one of the most important deities. One myth tells of a girl who was swept away by the river and taken by Apo Litao, eventually becoming his wife and the queen of the waters. This figure, described as a mermaid or sirena, had the power to kill those who disrespected her but granted gifts to those who honored her.

In addition to Apo Litao, water was seen as a cosmic force that connected the living with the dead. The deceased were often buried with offerings to ensure safe passage across the river to the afterlife, a concept shared by many indigenous groups across the Philippines.

Food offerings

The Ilocano ritual of "Atang" aims to appease malevolent spirits, or anitos, and drive away evil influences. In Ilocano culture, there is a strong belief that spirits—whether of the deceased or from other realms—coexist with the living and must be honored whenever they are disturbed or offended. The ritual is performed during wakes and on Pista ti Natay (All Souls' Day).[83]

During an Atang ritual, plates of food are meticulously prepared, featuring delicacies such as kankanen (sticky rice cakes), bagas (uncooked rice), boiled eggs, búa (betel nut), gawéd or paan (piper leaf), apóg (lime powder), basi (fermented sugarcane wine), and tabako (tobacco). Traditionally, offerings to the anitos were placed on platforms called simbaan or in trees, caves believed to be inhabited by spirits.

However, due to the influence of Christianity, these offerings are now typically placed in front of a photo of the departed or an image of Jesus, Mary, or the Holy Family, either in homes or at gravesites. Following this, family members and mourners engage in prayers to honor the deceased and seek protection from malevolent spirits, ensuring that these spirits remain peaceful and benevolent toward the living. The Ilocano belief in spirits extends to supernatural beings such as the katawtaw-an, spirits of infants who died unbaptized and were thought to pose a danger to newborns.

Crocodiles (bukarot), once abundant in the Philippines, were deeply respected by the Ilocanos, who regarded them as divine creatures and symbols of their ancestors. As a sign of respect, Ilocanos would offer their first catch to crocodiles (panagyatang) to avoid misfortune.[84]

Human Sacrifice

Sibróng was a significant ritual in early Ilocano belief, deeply tied to headhunting and human sacrifice. This practice was typically performed during the death of community leaders or members of the principalía to ensure their safe passage to the afterlife. The ritual involved a figure called the mannibróng, who was responsible for carrying out the executions.

There were two primary types of sibróng. The first type required the taking of a victim's head, which was placed in the foundation of a bridge, symbolizing strength and protection. The second, known as panagtutuyo, involved the dying person raising a certain number of fingers, which signified how many individuals needed to be sacrificed to accompany their soul to the afterlife. In some instances, instead of actual death, those chosen for sacrifice would have their fingers severed as a symbolic offering.[85]

Another aspect of sibróng involved placing human heads in the foundations of buildings to provide spiritual protection and prevent damage.[86]

Remove ads

Culture

Summarize

Perspective

Literature

Pedro Bucaneg the Father of Ilocano literature

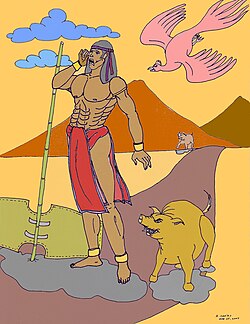

An illustration depicting the protagonist Lam-ang with his magical pets, a dog, and a rooster

Ilocano literature draws on traditional Ilocano mythology, folklore, and superstition.[87]

Epic or epiko, at the heart of Ilocano literature lies its epic poetry, with Biag ni Lam-ang (The Life of Lam-ang) being the most notable example. Believed to have originated in the pre-colonial period, the epic was preserved through oral transmission across generations of poets. Its first transcription is sometimes attributed to the 17th-century blind poet-preacher Pedro Bucaneg, often regarded as the "Father of Ilocano Poetry."[88][89]

However, historian Manuel Arsenio contends that the earliest written version was produced by Fr. Blanco of Narvacan in collaboration with folklorist and publicist Isabelo de los Reyes.The poem embodies core Ilocano values such as courage, loyalty, and respect for familial and ancestral ties, making it a crucial cultural artifact that has survived colonial influences.[90]

Poem, or dandániw in Ilocano, Ilocano poetry has a rich tradition that has evolved over centuries. Ancient Ilocano poets expressed their thoughts and emotions through various forms, including folk and war poems and songs (dállot), which are improvised long poems delivered in a melodic fashion. These poetic forms not only served as artistic expressions but also as vehicles for cultural transmission.[91]

Proverbs, or pagsasaó, are an essential aspect of Ilocano literature. These succinct sayings encapsulate moral lessons, cultural values, and practical advice, serving as guiding principles in daily life. They are often shared during conversations, gatherings, and even formal occasions, reinforcing social bonds and community cohesion.

"Ti tao nga sadot, uray agtodo ti balitok, haan to pulos a makipidot."

"A lazy person, even if it rains gold, will not pick one"

Literary Duels or Búcanégan represents the unique literary duel tradition of the Ilocanos, akin to the Tagalog Balagtasan. Named after Pedro Bucaneg, these verbal jousts involve participants engaging in poetic debates, showcasing their wit, creativity, and linguistic prowess. Bucanegan not only entertains but also serves as a platform for social commentary, allowing the community to address relevant issues through the lens of humor and poetry.[92][93]

Riddles or burburtia, are another important form of Ilocano literature. These clever wordplay challenges test the intellect of both the speaker and the audience, fostering critical thinking and community engagement. Riddles often draw from nature, everyday life, and cultural references, making them a delightful and educational part of Ilocano oral tradition.[citation needed]

"Sangkabassit a waig, Naaladan ti pino a kakawayanan." - Mata

"A little lake, Fence in by a fine bamboo strip" - Eye

Publications

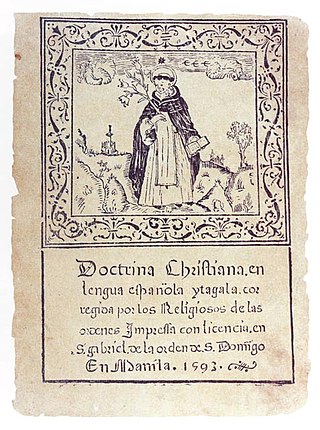

Ilocano literature began to flourish during the Spanish colonial period, with the publication of the Doctrina Cristiana in 1621 by Francisco Lopez. This was the first printed book in Ilocano, marking a significant milestone in the written tradition of the Ilocano people. Such works, including Sumario de las Indulgencias de la Santa Correa, played a pivotal role in the spread of literacy and education among the Ilocano-speaking population, contributing to the cultural and intellectual development of the region.

In the late 19th century, Ilocano literature gained further recognition through the efforts of Isabelo de los Reyes, a prominent Ilocano scholar and writer. He published works like Ilocandias (1887), Articulos Varios (1887), and Historia de Filipinas (1889). His two-volume Historia de Ilocos (1890) became a cornerstone in documenting the history of Ilocos. Another significant literary achievement during this period was Matilde de Sinapangan, the first Ilocano novel, written by Fr. Rufino Redondo in 1892.

20th century

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the emergence of prominent Ilocano authors. Leona Florentino, often referred to as the "National Poetess of the Philippines," became a prominent figure in the literary landscape despite mixed critical reception of her sentimental poetry. Other notable authors include Manuel Arguilla, whose works capture the essence of Ilocano culture during the early 20th century, and Carlos Bulosan, whose novel America is in the Heart resonates deeply with the Filipino-American experience. Additionally, Isabelo de los Reyes played a pivotal role in preserving Ilocano literary heritage, contributing to the publication of essential works like the earliest known text of Biag ni Lam-ang.

The 20th century marked a significant turning point in Ilocano literature, characterized by a growing recognition of its cultural importance. Authors like F. Sionil Jose and Elizabeth Medina emerged as influential voices. GUMIL Filipinas, or "Gunglo dagiti Mannurat nga Ilokano iti Filipinas", is an association of Ilocano writers in the Philippines. It's also known as the Ilokano Writers Association of the Philippines.

GUMIL's goals include providing a forum for Ilocano writers to work together to improve their writing, enriching Ilocano literature and cultural heritage, publishing books and other writings, and helping members pursue their writing careers. GUMIL has many active members in provincial and municipal chapters, as well as in overseas chapters in the U.S., Hawaii, and Greece. GUMIL was once the first website to focus on Philippine literature.

First published in 1934, Bannawag is widely regarded as the "Bible of the North." It reaches the heart of Northern Luzon, as well as Visayas, Mindanao, and Ilocano communities in Hawaii and America's West Coast. Bannawag highlights family values in its stories and articles and through the years has continued to inspire, entertain, and empower its readers. Bannawag (Iloko word meaning "dawn") is a Philippine weekly magazine published in the Philippines by Liwayway Publications Inc. It contains serialized novels/comics, short stories, poetry, essays, news features, entertainment news and articles, among others, that are written in Ilokano, a language common in the northern regions of the Philippines.

Bannawag has been acknowledged as one foundation of the existence of contemporary Iloko literature. It is through the Bannawag that every Ilokano writer has proved his mettle by publishing his first Iloko short story, poetry, or essay, and thereafter his succeeding works, in its pages. The magazine is also instrumental in the establishment of GUMIL Filipinas, the umbrella organization of Ilocano writers in the Philippines and in other countries.[94]

Music and Performing Arts

Music

Ilocano music is deeply embedded in the cultural traditions and way of life of the Ilocano people, reflecting the various stages of their life cycle—from birth through love, courtship, and marriage, to death. It emphasizes significant life events, showcasing the emotions and experiences associated with them. Traditional forms of Ilocano music include duayya (lullabies), dállot (improvised chants for weddings and courtships), and dung-aw (lamentations for the deceased). These musical expressions not only convey heartfelt emotions but also serve as a lens through which one can understand Ilocano values, history, and social interactions.[95][96]

Dung-áw, a solemn form of lamentation performed during funerals. It serves as a poetic expression of grief, where the reciter's genuine sorrow is conveyed through wailing and verse. The mournful tones and rhythm of the dung-aw stir emotions in both the performer and listeners, fostering a collective sense of loss and remembrance for the deceased.[97]

Dállot, an improvised, versified poem delivered in a chant or singing, often performed during joyful occasions such as weddings, courtships, and betrothals. An example of this is "Dardarepdep," (dream) which is a harana (serenade) in Tagalog, where love songs are sung to woo a woman. The term dállot originates from the Ilocano words for poem (dániw) and cockfight (pallót), blending heart and mind into poetic expressions of love, commitment, and community. Its performance is a creative showcase of spontaneous poetic artistry, celebrating unity and harmony in social gatherings.[98]

A notable Manlilikha ng Bayan, Adelita Romualdo Bagcal, has dedicated her life to preserving and promoting the Ilocano oral tradition of dallot since childhood. She is the last remaining expert in this art form, which focuses on courtship and marriage. Through her performances at social events, she demonstrates her mastery of the Ilocano language and its intricate literary devices.[99][100]

Duayya, a traditional Ilocano lullaby sung by mothers to soothe and rock their babies to sleep.[101]

Folk music

Ilocano folk music can be categorized into duwayya, dállot, and dung-áw. These musical forms reflect themes revolving around love, family, nature, and community. The melodies are simple yet powerful, serving as both a form of entertainment and a means of passing down stories, traditions, and moral lessons through generations. Here are some notable Ilocano folk songs:[102]

- Ayat ti Ina (Love of a Mother) – Expresses a mother's unconditional love and care for her child, reinforcing the value of family in Ilocano life.

- Bannatiran – Refers to a native bird from Ilocos, using it as a metaphor for a woman's sought-after brown complexion.

- Dinak Kad Dildilawen (Do Not Criticize Me) – A patriotic song expressing pride in one's identity and origins.

- Duayya ni Ayat (Love's Lullaby) – A man expresses his love for a woman, asking her to stay loyal and not change her heart.

- Dungdungwen Kanto (Lullaby of Love) – A romantic song typically sung at weddings, symbolizing love and care between partners; can also be a lullaby.

- Kasasaad ti Kinabalasang (The Life of a Maiden) – Advises young women to carefully consider their decisions before marriage, highlighting responsibilities and challenges.

- Manang Biday – A song about the traditional courtship of a maiden named Biday, emphasizing Ilocano courtship rituals and modesty.

- Napateg a Bin-i (Cherished Seed) – Compares a woman to a cherished seed, illustrating her value and importance.

- No Duaduaem Pay (If You Still Doubt) – A reassurance song where a lover asks his beloved to trust in the sincerity of his love despite her doubts.

- O Naraniag a Bulan (O Bright Moon) – A fast-paced love song expressing sadness and desperation for enlightenment while contemplating tragic love.

- Osi-osi – A folk song depicting playful yet respectful courtship practices in Ilocano society.

- Pamulinawen – A song about a woman with a "hardened heart" who disregards her lover's pleas, reflecting unrequited love and resilience.

- Siasin ti Agayat Kenka? (Who is in Love with You?) – A song of persistent love where the singer passionately declares devotion and hopes his beloved accepts his feelings.

- Teng-nga ti Rabii (Midnight) – A lover's song about being awakened by the image and voice of his beloved at midnight, emphasizing longing and desire.

- Ti Ayat ti Maysa a Ubing (The Love of a Child) – Portrays the pure, unbiased, and unconditional love of a child, highlighting innocence and sincerity.

Dances

Panagyaman dancers showcasing Ilocano steps in Balaoan, La Union.

Binatbatan dancer during town fiesta at Vigan, Ilocos Sur

Damili dancer displaying Ilocano steps in San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte.

Ilocano dances are performed during rituals, celebrations, and social gatherings. They draw influences from Cordilleran (Igorot), Spanish, and American dance movements.[103]

Kumintang, or gumintang a traditional dance step associated with Ilocano values, especially the idea of saving for the future. While variations of the kumintang exist in other parts of the Philippines, the Ilocano version involves inward arm movements and half-closed hands. This reflects the practical, forward-thinking nature of the Ilocano people.[103]

Korriti, a dance step showcases the energetic and hardworking spirit of the Ilocanos. It symbolizes the fast and lively movements needed to work in the fields or search for opportunities. The quick footwork represents their determination and resilience in earning a living.[103]

Sagamantika, a gentle, flowing dance step that involves moving forward and backward. It symbolizes an important Ilocano belief: no matter where you go, you will always return to your roots. This step reflects the importance of home and the lasting connection to where one was born and raised.[103]

Folk Dance

Ilocano folk dances vary across the region, with dances often being tied to specific locations and communities. They are performed for a variety of occasions, including courtship, community events, and rituals.[104]

- Agabel – Weaving dance.

- Agdamdamili – Traditional pot dance.

- Ba-Ingles – A dance from Cabugao, brought by early English tradesmen.

- Binatbatan – Depicts cotton-beating to separate fibers.

- Binigan-bigat – Courtship dance where a boy pleads for a girl's love.

- Chotis Dingreña – Social dance performed as an intermission.

- Dinaklisan – Fishing dance showing fisherfolk's labor.

- Habanera – Traditional Spanish-influenced dance.

- Ilocana a Nasudi – Symbolizes the purity and modesty of Ilocana women.

- Innalisen – Traditional Ilocano dance.

- Jota Aragoneza – Ilocano Jota dance from Paoay, Ilocos Norte.

- Jota Moncadeña – Ilocano Jota dance from Moncada, Tarlac.

- Kinnalogong – Traditional Ilocano dance.

- Kinoton – Humorous dance mimicking someone bitten by ants.

- Kutsara Pasuquiña – Festive party dance.

- Pandanggo Laoagueña – Lively Ilocano courtship dance.

- Rabong – Celebrates bamboo shoots, a delicacy.

- Sabunganay – Represents a young girl not yet ready for courtship.

- Saimita – Traditional Ilocano dance.

- Sakuting – Theatrical dance from Abra province.

- Sileledda-ang – Courtship dance expressing deep affection.

- Surtido Banna (Espiritu) – Ilocano waltz variation.

- Surtido Norte – Mix of Ilocano dance steps symbolizing thriftiness.

- Vintareña – Dance for social events like weddings and baptisms.

Drama

Ilocano drama, or theater, includes the genres of zarzuela and comedia (or moro-moro), which have been performed for generations. Other local performances include the dállot, a sung exchange about love between a man and a woman, and búcanégan, a tribute performance honoring someone.[105]

Zarzuelas, a type of musical theater that blends singing, dancing, and spoken dialogue. Introduced from Spain in the 19th century, it quickly became popular in the Ilocos region.[citation needed] Often centered on love stories with "boy-meets-girl" themes, zarzuela offers a mix of melodrama, comedy, and romance that appeals to audiences. One well-known Ilocano zarzuela, Tres Patrimoño, tells the life stories of three important people from Vigan, Diego and Gabriela Silang, Leona Florentino, and Padre Burgos, who all played significant roles in Philippine history.[106]

Moro-Moro, also known as comedia, moro moro a theatrical form that gained popularity in the 19th century through Marcelino Crisólogo, particularly during fiestas in Vigan. It centers on the conflicts between Christians and Muslims, in contrast to zarzuela, which addresses social issues through music and dance. Moro-moro incorporates traditional elements such as battle scenes and religious themes, and it places a strong emphasis on costumes and elaborate staging to convey its historical narratives.[107][108]

Clothing and appearances

Pre-colonial

Before the arrival of the Spanish, Ilocanos, like many other indigenous groups in the Philippines, dressed simply yet stylishly, with both men and women paying attention to their appearances. Their practices were a reflection of their social norms, available resources, and interactions with neighboring Cordilleran groups such as the Tinguians.[109]

Clothing

Both Ilocano men and women wore an upper garment called bádo or báru. These garments were made similarly to the koton of the Itneg people and fine red "chininas" crepe from India, with silk reserved for the upper class.[9] Men wore a collarless, waist-length fitted jacket with short, wide blue or black sleeves. Women's upper garments were also fitted but extended to the waist. To complete their attire, women often used a multicolored shawl, which was either draped over the shoulder or tied below the arm. Upper-class Ilocanas wore rich materials such as crimson silk woven with gold (songket), adorned with thick fringes for decoration.[109][9]

For the lower garment, Ilocano men wore a long, narrow loincloth called baág, anúngo, or bayakát, which was richly colored and often featured gold stripes. It was wrapped around the waist and passed between the legs, covering the mid-thigh area. Alternatively, they sometimes wore trousers similar to those of the Tagalogs.[9] Women's lower garments included a type of overskirt called salupingping, worn over a white underskirt. The skirt was gathered at the waist, with pleats placed on one side.[109]

Hair Care

Both men and women in Ilocano society took great care of their hair. They used natural shampooing decoctions made from the bark of certain trees, coconut oil mixed with musk and other perfumes, and gogo or entada phaseoloides (a kind of herbal shampoo) to keep their hair shiny and black. Lye made from rice husk was also used, and it continues to be used in some areas of Ilocos today.[109] Women twisted their hair into charming buns on the crowns of their heads, while men often pulled out their facial hair using clam-shell tweezers, leaving them clean-shaven.[110]

Jewelry and Adornments