Loading AI tools

佛教與基督教同為世界上的主要宗教,釋迦牟尼佛在耶穌約五百年之前誕生。而《希伯來聖經》在耶穌誕生前約1,500年前開始寫,歷經1,000多年寫成。從孔雀王朝起,佛教開始向印度各地、中東以及中國傳播。而基督教起源於猶太地區,從西元一世紀傳往羅馬帝國及地中海沿岸。公元前331年到前325年馬其頓亞歷山大大帝東征至印度河,希臘人其後更在該地區成立了多個印度-希臘王國,不單將希臘文化帶至印度,也令印度文化包括佛教傳播至中東、埃及和希臘。公元前722年與586年以色列王國與猶大王國分別被亞述與巴比倫帝國毀滅,開始了猶太人流亡期,並開始將舊約聖經影響巴比倫、波斯等東亞地區。有學者包括普林斯頓大學宗教系教授伊萊恩·柏高絲,透過分析早期基督教的偽經和佛教經文,推測兩者有關聯。在諾斯底教派的多馬福音中[1] ,柏高絲認為「有部份和佛教相似,這些早期的經文很可能受到當時已經發展成熟的佛教傳統影響。」[2] 另外,艾伯特·約瑟·艾德蒙斯認為約翰福音裏含有一些佛教與道教的概念。[3] 其它學者亦曾比較路加福音和方廣大莊嚴經裏關於耶穌誕生和佛誕相似的描述。[4]

偽經多馬福音成書之時(公元200年),有不少佛教的傳教者居住於埃及的亞歷山大港。[2] 歷史學家認為公元4世紀時,天主教的修道院開始在埃及建立,而當地的修道院的結構和同時期的佛教寺院有相似之處。[4]

13世紀時,歐洲的旅行家如柏郎嘉賓及魯不魯乞在他們的旅行報告中描述了佛教的經文、戒律、寺院生活、宗教儀式和冥想修行的法門,和當時聶斯脫里派(即景教)極為相似。[5] 16世紀早期,天主教的傳教士如聖方濟·沙勿略亦曾提及東方的佛教。[5] 同時期的葡萄牙殖民主義者在斯里蘭卡禁制佛教,並沒收了寺廟的財產,後來斯里蘭卡的荷蘭及英國統治者亦一樣禁止佛教。[5] 但葡萄牙的歷史學家地牙哥·康托發現原來天主教的聖約沙法就是印度的釋迦牟尼佛,並向羅馬教廷報告。[6]

18世紀歐洲的大學開始對梵文研究,引起更多人對佛經的興趣。[5] 19世紀開始有西方人信佛教,20世紀初更開始有西方人在佛寺成為僧侶。[5] 在20世紀,基督教和佛教的教徒之間展開更多的交流,如天主教徒湯瑪士·梅爾頓、韋恩·提士道、大衛·史坦度-拉斯特、修女凱倫·岩士唐[7] 以及佛教徒如佛使比丘、一行禪師和第十四世達賴喇嘛·丹增嘉措都致力尋找兩個宗教的對話。[8] 他們都認為基督和佛陀的教誨並不一定衝突,而是可以互補和對照。[9][10][11] 世界文化歷史學者阿諾爾德·約瑟·湯因比更認為基督教和佛教的接觸會是這個世紀重要的事情。[12]

在耶穌誕生以前,佛教在印度、錫蘭、中亞廣泛流傳。[13] 佛教的部份清規,如非暴力、慈悲和守戒律等佛教理念與中東耶穌傳的教義和聖經有相近之處,如愛神、愛人,守十誡。最主要也是最大的不同之處是佛教的強調四諦、十二因緣、緣起性空,最終能涅槃解脫,與基督教的恩典、因信稱義、惟一真神、罪與救贖不同等。

前331年-前325年馬其頓亞歷山大大帝東征至印度河,兩地文化初次正面交鋒。

據威爾·杜蘭特在1930年代指出,孔雀王朝(約前321年-至約前187年)的阿育王曾遣僧侶到印度、斯里蘭卡、敍利亞、埃及以至希臘傳教,或許成為後來基督教的榜樣。[14] 而據阿育王的史官記載,希臘其中一個君主菲拉度弗斯亦曾遣使至孔雀王朝[15]

孔雀王朝開始,佛經及佛寺已經傳播至西北方的安息(亦稱作帕提亞帝國,今伊朗地區)。[16]

孔雀王朝滅亡後,希臘和印度人在印度北部巴克特里亞成立了多個印度-希臘王國,包括大夏國(前250年-前125年)。這些中亞國家成為東西文化的熔爐,發展出獨特的希臘式佛教和希臘式佛教藝術。不單將希臘文化帶至印度,也可能將佛教傳播至中東、埃及和希臘。同一時期佛教亦開始透過絲綢之路傳入漢朝的中國。

有學者認為早期的波斯先知曾接觸過佛教信仰,並預言耶穌降生,如神學家亞歷山太的革利免稱在公元前2世紀:

| “ | 有希臘的哲學家、埃及的預言家、亞述、高盧、凱爾特、巴克特里亞、北非各地不同宗教的人。來自波斯的先知在預言以色列將會有救主基督耶穌降生。印度的修行者也不少,而他們當中可以分為兩類:沙門和婆羅門。

|

” |

亞歷山大的革利免亦提到釋迦牟尼:

| “ | 印度的修行之中有相信釋迦牟尼的,他們形容釋迦牟尼為聖潔的尊者。

|

” |

| ——Stromata (Miscellanies), Book I, Chapter XV | ||

公元3至4世紀,猶太教徒如希普利圖斯和伊比凡尼奧斯 提及斯古底亞奴斯曾在約公元前50年去過印度,並帶回來「兩正道」,其弟子德勒本圖斯更自稱為「佛」,在猶太地區廣為人知。而他們的教義很可能是摩尼教的先驅。[17]

| “ | 德勒本圖斯繼承了老師的財產和經文來到巴勒斯坦,改稱自己為佛陀,在以色列廣為人知,被譴責之後移居波斯。

|

” |

希普利圖斯,一個在羅馬的希臘語基督徒,在235年提到了印度的僧侶:

| “ | 在印度人之中有婆羅門,過著自給自足的生活,不吃肉食...他們稱神就是光,但不是看得見的光、太陽或火焰,不是聽得見的聲音,而是真理(gnosis)的顯露,將自然的奧秘傳授給智者。 | ” |

希臘有巴蘭與約沙法(Barlaam and Josaphat)的傳說,故事裏約沙法本為王子,後來出家,隨僧人巴蘭修行。一般認為聖約沙法的傳說其實是釋迦牟尼的生平故事,經過阿拉伯文及喬治亞文翻譯而來。這傳說常被認為是7世紀大馬士革的聖約翰所書,但最早的紀錄出於11世紀喬治亞僧侶阿索斯的尤錫米烏斯的敍述。而約沙法這個名字(喬治亞語:Iodasaph,亞拉伯語:Yūdhasaf 或 Būdhasaf)和梵文中菩薩(Bodhisattva)的讀音接近。

聖巴蘭與約沙法日在東正教廷是8月26日,在羅馬天主教廷是11月27日。在中世紀時這傳說也被翻譯成希伯萊文。佛陀的故事成為基督教和猶太教的傳說之一。[19]

現時有兩種學說,一種認為佛教受基督教影響,一種認為基督教受佛教影響。前者認為大乘佛教形成的時候剛好是基督教福音成書的年代,故推論當時的佛經受福音影響。後者則以巴利文的原始佛教經文和早期基督教經文比較,認為佛教的學說在耶穌誕生之前四百多年已經廣泛流傳,因此可能佛教的教義和寓言被吸收到基督教的聖經經文之中。

伊萊恩·柏高絲在其著作諾斯底福音(1979年)以及信仰以外(2003年)指出多馬福音及拿戈瑪第經集的經文和佛經極相似。柏高絲認為假如把多馬福音裏的耶穌的名字換成釋迦牟尼的話,經文的許多教誨幾乎和佛經所說的一樣。[20] 學者菲利普·珍瓊士 [21] 及愛德華·公茲[22] 都持相似意見,認為印度人和諾斯底教派(又稱多馬基督徒)有接觸。多馬福音及拿戈瑪第經集在1945年埃及被發現後,引起不少學者注意,因為多馬福音比其它福音成書時間較晚,而和其它福音沒有直接關聯,可以視為歷史參考。但大多數學者則認為諾斯底教派後來被其基督教視為異端,多馬福音亦沒有收錄在新約之中,因為它和其它的四福音書內容和保羅書信神學觀的多有衝突、且成書晚、故不被採信。

1816年佐治·史坦利·法伯在其著作偶像崇拜起源的歷史證據(The Origin of Pagan Idolatry Ascertained from Historical Testimony)指出關於耶穌和釋迦牟尼的描述極為相似,認為這可能不是偶然。[23]

比較宗教及東方研究學者馬斯·梅勒在1883年在其著作印度:它告訴我們甚麼(India: What it Can Teach Us)指出「佛教和基督教有許多巧合地相似,是我們無法否認的。而佛教比基督教早至少四百多年存在。非常希望有人能夠透過歷史的證據證明佛教影響了早期基督教。我一生都在追尋這樣的渠道,至今我仍沒有找到。」

1897年,萊比錫大學的魯道夫·舍伊道教授在著作「佛教傳說與耶穌生平」(The Buddha Legend and the Life of Jesus)指出佛經與聖經有五十多處相似之處。在此之後,1918年耶魯大學梵文及比較哲學教授愛德華·豪本勤甚至認為耶穌的生平、試練、神跡、寓言以至弟子都是來自佛教的傳說。[24] 比較近期的研究有歷史學家傑瑞·本德利 的著作「舊世界的文化交融」(1993年)[25]、義大利撒丁島鄧肯·麥德列(Duncan McDerret)的著作「聖經與佛教徒」(2001)、奕波星的著作「佛教總論:佛陀的構成、法句經與宗教哲學」(2004年)[26] 認為基督教受到佛教影響。

坎特伯利基督教大學宗教研究學者博哈特·舒瑞爾(Burkhard Scherer)的網頁 Jesus is Buddha[27] 引用2007年佛教研究博士基斯·連特納(Christian Lindtner)的研究比較了巴利文和梵文的佛經以及希臘文的聖經之間的相似性。有反對者認為相似的原因只是因為希臘文和梵文是同一語系的語言。

美國北卡羅萊那大學教堂山分校宗教研究教授湯瑪士·杜域特(Thomas Tweed)在1879年-1907年間,以及艾伯特·舒懷薩1906年的著作都持反對意見,認為即使佛教對基督教有間接的影響,但說耶穌出自佛教傳說如同比較孔子與耶穌則是沒有根據、也無從證實的無稽之談。[28]

亞歷山大城的神學家斐洛在公元前10年記載,在公元前一百年左右在埃及開始有一個特拉普提派,但在斐洛的時代已經不清楚特拉普提派的起源。據早期基督教歷史學者該撒利亞的優西比烏(約275年—339年)記載,斐洛是天主教修道院的最早的推行者。[29]

語言學家撒查利亞斯·芬地(Zacharias P. Thundy)認為特拉普提(Therapeutae)其實是巴利文上座部佛教(Theravada)的希臘文翻譯。特拉普提派的寺院禁慾苦行的修行方式和佛教很相似,所以芬地認為他們其實就是阿育王派往西方的佛教使節,而他們直接影響了早期天主教的構成。[30] 但除了名字和修行方法的相似性,暫時並無考古證據支持這種說法。

艾爾瑪·告魯伯(Elmar R. Gruber)及宗教歷史學家荷爾格·克爾斯頓(Holger Kersten)認為耶穌可能曾經像特拉普提派那樣修行,因此學習了佛教教義。[31] 他們引用牛津的新約研究者巴納特·史特拉特(Barnett Hillman Streeter)亦指耶穌的山上寶訓和佛教教義有相似之處。[32]

苦行主義或禁慾(Asceticism)是早期天主教和佛教相似之處,而猶太教與基督教是不主張禁慾或苦行的,根據猶太百科全書:

| “ | 禁慾主義是源自一些認為人的慾望令生命痛苦,又或者人類有原罪的宗教。因此佛教和基督教都產生了禁慾修行的寺院制度。早期基督教(天主教)孟他努派及其它教派都認為禁食、禁止性慾及其它慾望是修行達致聖潔的方法。類似的想法在佛陀的教導中可以找得到。兩個宗教都主張修道者應過著清貧和貞潔的獨身生活,而透過禁食或守各種的戒律去減低控制肉體的慾望。

|

” |

耶穌在童年到成年講道之間有許多年並沒有任何記載,被人稱為耶穌行成謎的歲月,有人甚至推測耶穌有機會到了印度或西藏。1887年一名俄羅斯的情報員尼古拉斯·諾多維奇曾去過印度北部拉達克的一個藏傳佛教寺廟(Hemis Monastery),並聲稱在佛寺裏看到關於聖伊薩事跡的手稿(Saint Issa,耶穌名字的阿拉伯譯音)。他將之翻譯為法文La vie inconnue de Jesus Christ並在1894年出版,該書隨即被翻譯為英文、德文、西班牙文及義大利文。

諾多維奇的說法受到質疑。德國的東方研究學者馬克斯·繆勒和該佛寺通訊(1956年,指並無證據顯示諾多維奇曾到過這間寺院,並向外界展示他得到佛寺主持的簽名信否定。[34] 但亦有其它人,如印裔英國宗教學者(亦是一位喇嘛)阿希達南達於1887年親身到訪該寺廟,也聲稱自己看到同樣的手稿,並將其經歷及經文翻譯為英文。[35]

然而,藏傳佛教的起源為西元六世紀(唐朝文成公主時期),與耶穌在世時間(西元前4年-西元30年)差了六個世紀,此證據在時間歷史上仍有矛盾。雖然這些說法眾說紛紜,新紀元運動以此作為自己信仰的證據。[36]

據歷史學者傑瑞·本德利稱,即使未能確切證實兩個宗教的關係,但是兩教關於耶穌和佛陀出生、生平、教誨及死亡的形容都有相似之處。[37].但根據聖經記載,耶穌出生於客房馬槽,木匠家,隨即又成為難民逃難到埃及。與釋迦牟尼出生、早年生活不同。

佛教叢林制度和天主教修道制度有以下幾點相似:

釋迦牟尼和耶穌有以下幾點類比:

- 誕生的傳說:釋迦牟尼的母親摩耶夫人夢見白象從左側進入身體,並有僧侶預言兒子將會是君王或偉大的佛陀(覺悟者),後來從右側產下釋迦牟尼。聖母瑪利亞夢見天使[來源請求],預言兒子會是地上的君王,童貞懷孕,後產下基督。[39] 聖母抱著耶穌的雕像有如佛母抱著釋迦牟尼的雕像。

- 棕櫚向瑪利亞彎曲[來源請求],正如無憂樹向摩耶夫人彎曲一樣。

- 關於耶穌初生時先知西面以及強光的描述幾乎和釋迦牟尼初生時一樣。

- 猶大背叛耶穌,正如提婆達多背叛釋迦牟尼。

- 耶穌和釋迦牟尼都曾在水上行走。兩人都曾行醫治病人。[40][41]

- 耶穌收了十二門徒,死前門徒不認祂、背叛祂。釋迦牟尼廣收一千二百五十位弟子,常隨遊行。

- 耶穌死後第三日肉身復活,後升天。釋迦牟尼於世壽八十圓寂。

文獻殘卷Archelaos of Carrha(前278年)亦提到釋迦牟尼母親童貞懷孕,然後產下釋迦牟尼的傳說。 [42]。

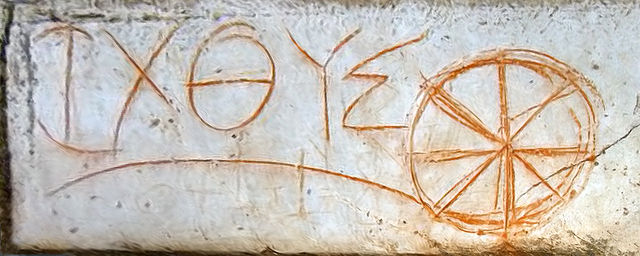

早期基督教並不使用十字架符號,但常用耶穌魚和凱樂(Chi Rho)符號,為躲避羅馬丁兵,恰與佛教的法輪形狀相似。這個符號是一個圓形,中間含有希臘字母XP,代表基督(Χριστός)。亦有人[誰?]認為這是君士坦丁大帝的創造,圓形代表太陽。在君士坦丁大帝之後,十字架才真正廣泛使用作為基督教的符號,最初都是圓圈之中加上十字,到中世紀後來才逐漸純以十字架出現。基督、聖母和各聖人的畫像裏頭頂常有圓形的光環,這一點亦類似佛教的佛陀和菩薩的型像。

英國巴利文學者利斯·大衛斯相信特拉普提派和佛教相關:「看看西藏喇嘛剃頭的僧侶、鐘與唸珠的運用、類似教宗和主教的多層等級、各種儀式和節日以及對貞潔的崇尚等等,和天主教是何等相似。」[43]

一般認為念珠是印度各宗教常用,後來透過伊斯蘭教傳到歐洲,但亦有人認為東方基督教一早已有用念珠祈禱,念珠有三十三顆,象徵耶穌基督的歲數。現在天主教在唸玫瑰經時亦有使用玫瑰念珠的習慣。[44]

合什行禮是印度各教常用的手勢,既用以打招呼,也在祈禱時用。這是猶太教沒有的,但在中世紀的藝術裏卻有天主教徒合什祈禱的畫面。[45]

佛教學者查理斯·艾利奧特認為從天主教和佛教種種相似的禮儀習俗、獨身生活、禱告唸經和他們共用的符號如鐘、念珠,很難相信兩者是獨立發展出來。[46]

有另一種看法是基督教影響佛教。有人認為孔雀王朝阿育王派佛教使者出使亞歷山大城,未必是埃及的亞歷山大城,而是位於巴克特里亞高加索的亞歷山卓(今阿富汗地區),因為當地的印度-希臘王國正是大乘佛教開枝散葉的主要發源地。大乘佛教發展較晚,大約在前2世紀至7世紀左右,不少大乘佛教經典成書於前1世紀。故此亦有人認為有機會是基督教影響佛教。[47][48]然而反對者認為,基督教與猶太教是一神信仰與佛教有根本的差異,況且一世紀基督門徒傳教路徑是往西班牙、羅馬方向,不是往印度方向。

由於佛經並沒有提及耶穌,佛教徒對基督的看法不一。第十四世達賴喇嘛·丹增嘉措曾說即使釋迦牟尼也有前生,故認為耶穌也有前世,並且認為耶穌一生普渡他人,所以可以說是一位菩薩(覺悟的人)。他認為耶穌和釋迦牟尼有很多共通點,從日常的修行方法以至經文裏的寓言。[49]

14世紀日本的峨山韶碩禪師亦認為福音是得道的人寫的。 [50]

根據希伯來人的信仰傳統,被(其他人用油)膏立是一種特別宗教儀式,意思指被選立的人,例如:祭司、君王及先知是神所選定的。在某些場合下一些器具也被油膏抹,用以預備宗教儀式。受膏的重要性,是因為設立聖職(代表會眾到神面前贖罪)的需要,而得以強調。例如:『受膏的祭司要取些公牛的血帶到會幕』(利未記)。在希伯來聖經之中,被稱為「彌賽亞」的多人不是神,無神性含義。猶太教與基督教在彌賽亞等一系列問題上都有分歧)。

彌賽亞是舊約聖經中受膏者的意思,在舊約時代的以色列,只有三種職份才可以被膏立,分別是王,先知和祭司。不論在舊約或新約,除了耶穌之外,沒有一個人能夠兼備這三個身份,正因為耶穌是王(馬太福音2章2節),是先知(約翰福音6章14節),也是祭司(希伯來書9章11節),所以祂就是真正的受膏者,也就是希臘文中基督的意思。

在《新約聖經》中,基督是指等候已久而來臨的救世主。聖靈如鴿子般降下,且有聲音被施洗約翰聽見,見證耶穌就是基督、就是舊約所有 神的子民素來所盼望的那位——彌賽亞。耶穌多次給他的門徒證明自己就是基督,並且在他受審時三次聲稱他就是基督。而在《新約》中祂從死裡復活、並且永遠不會再死,也見證了祂就是在《舊約》中所指的受膏者:彌賽亞(基督)。

基督一詞用來指代耶穌的神性,他是神(上帝)的獨生子,是在耶穌復活、升天後的稱呼,在《使徒行傳》中開始使用,此前耶穌的門徒都稱他為夫子或拉比,即為老師的意思。

漢學家馬丁·柏爾瑪則認為聖母瑪利亞和觀音相似,都是以慈祥的女性形象出現。佛教亦常常有觀音抱著嬰兒的塑像。[51]

在天主教盛行的國家如菲律賓,當地的華僑亦故意將觀音和聖母瑪利亞混淆。日本在鎖國政策 (1633年開始)禁止天主教傳播,當時亦有傳教士將聖母瑪利亞假裝成觀音(瑪利亞觀音),直至19世紀中葉日本再次開放宗教自由才停止。

基督宗教的聶斯脫留派是於公元六世紀由黎凡特地區的敘利亞傳入中國,在當時稱為景教。景教在北魏的時代傳入,在唐初時建立了不少大秦寺,在武則天時代受到佛僧道士攻擊。唐武宗會昌毀佛時,逾萬間佛寺被毀,景教也遭波及,於元朝時又一度興盛。明朝取代元朝後,景教衰微,十六世紀歐洲天主教傳教士至中國後,景教徒更是銳減。景教現存西安的景教大秦寺外型和佛塔相似,景教的經文在翻譯過程中亦套用了不少佛教術語,如《四福音》的作者,均改以「法王」稱呼:馬太是明泰法王、路加是盧珈法王、馬可是摩距辭法王、約翰喚成瑜翰法王;教堂叫作「寺」;大主教叫「大法王」;教士自然叫作「僧」。上帝的稱呼則取敍利亞文「Alaha」音譯,叫作「皇父阿羅訶」,亦有按照道教規則,以「天尊」稱之。天主教耶穌會在明朝傳入中國,當時的翻譯亦直接借用了一些道教和佛教用語,如上帝本來是指中國民間信仰的昊天上帝(同「天」、「帝」等詞,後世道教中演變為玉皇大帝),「聖母」也常常是女神的稱號,可以指佛母、瑤池金母、天后媽祖、臨水夫人、碧霞元君等。至清末以降,以天主教和新教為主的基督宗教各宗派才開始在中國大規模的發展。1949年中共建政後,包括基督宗教在內的所有宗教均遭到中國共產黨大幅的打壓。1980年代改革開放以後,基督宗教重新開始正常的崇拜與傳播活動,自此基督徒數目增長顯著。

在斯里蘭卡,佛教在葡萄牙、荷蘭及英國殖民力統治下受到基督教很大的影響。到了19世紀末,受到美國佛教徒亨利·斯太爾·奧爾科特的啟發,以及在19世紀帕訥杜勒佛教僧人瞿那難陀和基督教牧師的辯論中,引發起民眾的本土佛教復興運動。

在南韓、香港、澳門、新加坡、台灣等地除了佛教與道教,亦有不少比例的基督信徒,而在一些佛教傳統國家,如泰國和緬甸,基督信徒佔很小的比例。

20世紀中葉,佛教與基督教發生過長時間的論戰,佛教方面有煮雲法師、印順法師、聖嚴法師等參與,基督教方面有杜而未神父、吳恩溥等參與。

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.