热门问题

时间线

聊天

视角

可薩人

来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

Remove ads

可薩人,也譯作卡扎人、哈扎爾人(土耳其語:Hazarlar;阿塞拜疆語:Xəzərlər;巴什基爾語:Хазарҙар;韃靼語:Хәзәрләр,羅馬化:Xäzärlär;波斯語:خزر;烏克蘭語:Хоза́ри,羅馬化:Khozáry;俄語:Хаза́ры;匈牙利語:Kazárok;希臘語:Χάζαροι,羅馬化:Házaroi;拉丁語:Gazari[6][注 2]/Gasani[注 3][7])是一個半游牧的突厥語民族,他們在公元6世紀末建立了一個突厥語部落聯邦,形成了覆蓋今天俄羅斯歐洲部分南部的一個大型商貿帝國[8]。

Remove ads

名稱

他們的可汗名號是答剌罕。「可薩」一詞在德文有「異教徒」,希臘文有「匈奴騎兵」,在俄文與希伯來文有「牧羊人」,在阿拉伯語有「小眼睛」的意思,在亞美尼亞與格魯吉亞有「北方」的意思,在突厥語解為「遊蕩」,古代波斯史說可薩人好劫掠與長途奔襲,長矛是主要武器,亞洲人後來把類似於可薩人那樣生活的也稱為可薩人,在1480年代,格魯吉亞還有自稱可薩人的突厥語游牧民,哥薩克也源於此字。在車臣語中,「可薩」一詞可解為「美麗谷地」。

可薩汗國

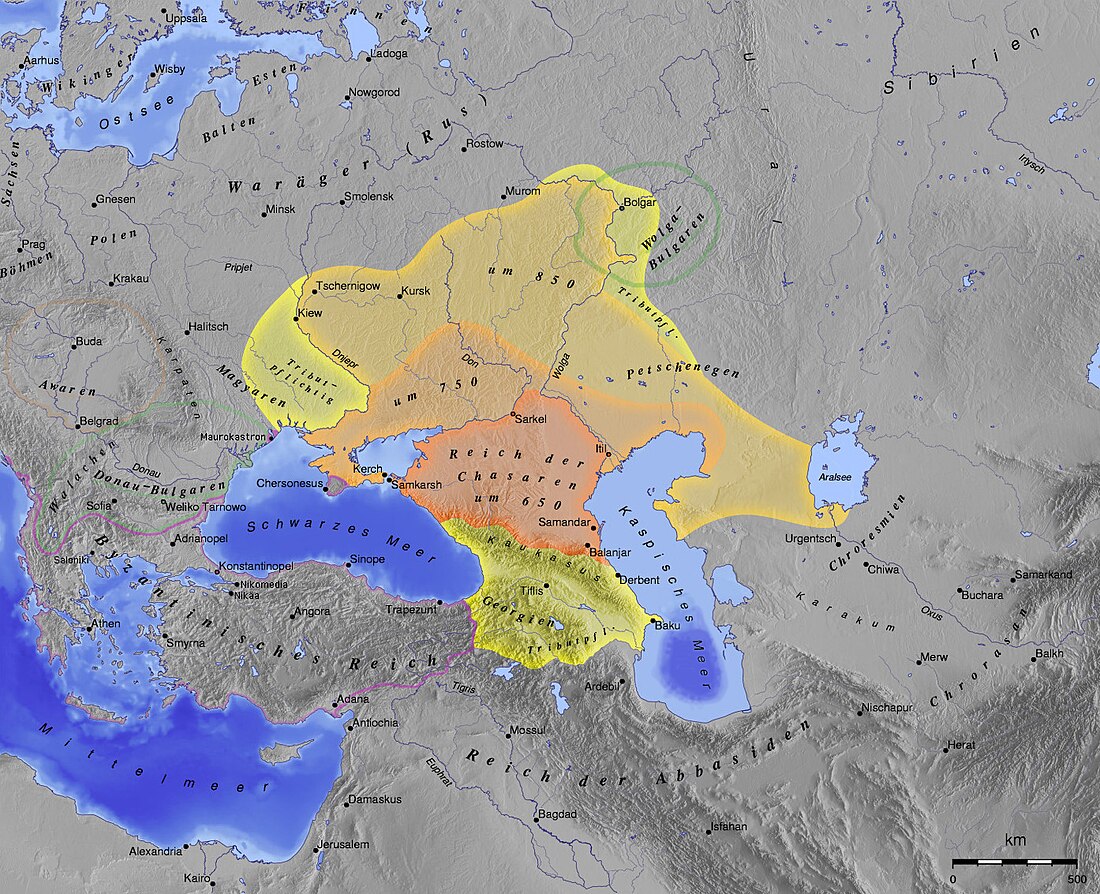

最早見於《隋書·北狄傳》,《舊唐書·西戎傳》和《新唐書·西域傳下》稱其為「突厥可薩部」,杜環《經行記》提到「苫國(敍利亞)有五節度,有兵馬一萬以上,北接可薩突厥,可薩北又有突厥」。他們與西突厥只有稀疏的關係(統治者是西突厥宗室,後來全然獨立),他們在公元7世紀下半葉,在北高加索草原伏爾加河中下游建立了強大的可薩汗國(或稱哈扎爾汗國、可薩利亞),這是西突厥崩潰後湧現的諸汗國中最強大的一個政權[9]。可薩汗國疆域東至今花剌子模、今西哈薩克斯坦州、西至多瑙河與今烏克蘭,達吉斯坦是核心,南至喬治亞、車臣、克里米亞、小亞細亞東北,控制着從伏爾加-頓河草原延伸至東克里米亞和北高加索的廣大地域[10],跨越東歐和西亞之間的主要貿易大動脈,成為絲綢之路北道上的一個比較重要的中轉站,也是中世紀世界最重要的貿易帝國之一,在中國、中東和基輔羅斯之間的十字路口扮演着重要的商業角色[11][12]。

可薩人作為的西突厥附屬一度與東羅馬帝國聯盟共同對抗薩珊波斯帝國。西突厥崩潰後可薩汗國逐漸成型,汗國長期成為東羅馬帝國和草原游牧民族以及倭馬亞王朝之間的緩衝國。東羅馬帝國說服阿蘭人攻擊可薩人從而削弱其對克里米亞和高加索的控制,同時力求與北邊崛起的基輔羅斯和解以便向他們傳播基督教[13]。965到969年間,基輔羅斯大公斯維亞托斯拉夫·伊戈列維奇攻陷了可薩首都阿的爾,可薩汗國就此滅亡。

要確定可薩人的起源,需要密切研究他們的語言,但這一課題的困難之處在於,可薩人沒有留下任何本土語料,而且可薩汗國是多語、多民族的。

通常認為可薩人最初的宗教是騰格里信仰,就像北高加索匈人和其他突厥族群一樣[14]。可薩汗國的民族有突厥語部落、波斯人、烏戈爾人、斯拉夫人、哥德人和高加索人等等,這樣的多民族人口似乎是騰格里信徒、猶太教徒、基督教徒和穆斯林等多種宗教的混合[15]。12世紀的兩位西班牙猶太學者猶大·哈列維和Abraham ibn Daud認為,可薩汗國的統治階層在8世紀皈依了拉比猶太教,但國內民眾對猶太教的接受程度還無法確定[16]。

Remove ads

歷史

後來形成可薩帝國的部落[注 4]並非一個單一族群聯盟,而是臣服於一個核心突厥統治者的草原游牧民族集團[17]。許多突厥族群,例如烏古爾突厥(包括蘇路羯、歐諾古爾人和保加爾人),他們曾是鐵勒聯盟的一部分,很早就受到沙比爾人的驅逐而向西遷徙(沙比爾人則早在4世紀就為了逃脫阿瓦爾人而遷至伏爾加河-裏海-黑海地區),根據普利斯庫斯的記載早在643年已居住在歐亞大草原的西部[18][19]。他們似乎是在匈奴游牧政權崩潰後從蒙古高原和南西伯利亞往西遷徙的。這是一個突厥人領導的部落聯盟,民族組成五花八門,其中可能有伊朗人[注 5]、原始蒙古人、烏拉爾人和古西伯利亞人的氏族,他們在552年滅亡了一度統治中亞的柔然阿瓦爾人,隨後西遷,索格底亞那地區的其他草原游牧民族也加入其中[21]。

這一聯盟的統治集團可能來自西突厥的阿史那氏族[22],不過法國歷史學家康斯坦丁·祖克爾曼對阿史那在可薩的形成過程中起的作用持懷疑態度[注 6]。另外一些歷史學家則注意到中國和阿拉伯的史料記錄幾乎一樣,說明阿史那與可薩之間有很強的聯繫,並猜想聯盟首領是於651年失勢或被殺的乙毗射匱可汗[23];西遷途中,這一聯盟到達了阿卡齊爾的地盤[注 7],阿卡齊爾曾與東羅馬共同對抗阿提拉。

Remove ads

630年後稍晚,可薩政權開始有了雛形[24][25],它是從西突厥汗國分裂而來的。西突厥軍隊在549年驅逐了伏爾加河流域的阿瓦爾人,使得阿瓦爾人被迫遷至今匈牙利的潘諾尼亞平原。據歐洲歷史學家相信,到了568年,西突厥已在謀求與東羅馬的合作來攻擊波斯。佗缽可汗死後,更早的東突厥與稍晚的西突厥之間爆發了內戰,佗缽可汗指定的繼承人是阿波可汗,而另一個爭權者則是沙缽略可汗,即阿史那攝圖。

到了7世紀的第一個十年,阿史那的統葉護成功穩定了西突厥,並為拜占庭提供了關鍵的軍事協助[26][27],但他死後西突厥在唐朝的軍事打擊下進一步解體成兩個互相競爭的聯盟,每個聯盟由五個部落組成,統稱「十姓」或「十箭」。與此同時,西邊有兩個新游牧政權興起,即咄陸氏族統治的保加爾人舊大保加利亞和弩失畢聯盟(五個部落組成,故稱五弩失畢)[注 8]。咄陸在庫班河-亞速海地區挑戰阿瓦爾人,同時可薩人則向西鞏固。657年,蘇定方將軍對西突厥部落取得了重大勝利,唐朝取得對東突厥的宗主權,成為東突厥游牧政權的宗主國,而保加爾和可薩這兩個部落政權為爭取西部草原而戰。可薩佔了上風,保加爾人要麼屈服於可薩統治,要麼在阿斯巴魯赫的領導下,向西遷徙,穿過多瑙河,為巴爾幹半島的保加利亞第一帝國奠定了基礎(679年左右)[28][29]。

可薩政權因此脫離於這個受到唐朝打擊而四分五裂的北亞游牧帝國的邊界之外[23],為了更多的生存空間,開始自發向西、向北擴張。東北方向達到了伏爾加河下游、向西則征服了多瑙河和第聶伯河之間的地區,並使歐諾古爾-保加爾聯盟臣服之後,在670年左右,可薩汗國就這樣崛起了[30],成為西突厥解體後最西邊的突厥游牧政權。烏克蘭裔美國學者奧梅利安·普里察克認為,歐諾古爾-保加爾聯盟的語言將成為可薩汗國的通用語[31],可薩隨之發展為蘇聯學者列夫·古米廖夫所說的「草原亞特蘭蒂斯」(Степная Атлантида)[32]。歐洲歷史學家將可薩汗國強盛的時期稱為可薩和平,因為可薩成為了一個重要的國家貿易樞紐,使得亞歐大陸西部的商人能安全地在此地區行走和從商[33]。三百年後的公元1100年左右,一部名為波斯法爾斯的歷史典籍提到薩珊帝國的沙阿庫斯老一世為自己放置了三個寶座,一個代表中國,第二個代表拜占庭,第三個代表可薩。儘管這種後世的歷史描寫可能出自附會,因為可薩政權並不存在於這一時期,但這一傳說將可薩置於與兩個超級大國同等地位上,體現了可薩政權作為一個區域政權所留下的良好聲譽[34][35]。

Remove ads

東羅馬帝國對草原民族的總體外交政策是慫恿他們互相爭鬥。佩切涅格人在9世紀為東羅馬提供了大量協助以換取定期的貢品[36]。東羅馬也與古突厥結盟來對抗共同的敵人:7世紀早期他們與西突厥人合作對抗薩珊帝國。東羅馬起初稱可薩利亞為圖爾基亞(Tourkia),到了9世紀稱之為突厥人[注 9]。在626年君士坦丁堡被圍困之前和之後,希拉克略派出密使,後來則是親自前往第比利斯尋求突厥首領統葉護的幫助[注 10],並給他禮物,許諾將自己唯一的女兒優多西婭·歐皮菲尼婭公主嫁給他[38]。統葉護派出一支軍隊重創了波斯帝國,第三次突厥-波斯戰爭由此爆發[39]。東羅馬和突厥的聯合軍事行動打破了亞歷山大門(或裏海門),他們在627年洗劫了傑爾賓特,並圍困了第比利斯,東羅馬人此前可能已在此部署各種早期重力拋石機來破壞城牆。戰役結束後,統葉護將大約40,000名士兵留在了希拉克略手中(這一說法可能有些誇大)[40]。儘管這一歷史事件中的突厥人偶爾被認為是可薩人,但更有可能是古突厥人,因為可薩是在古突厥分裂之後(稍晚於630年)才出現[24][25]。一些學者認為薩珊波斯人從未從這次入侵造成的破壞中恢復過來[注 11]。

深藍:可薩直接控制;

紫色:勢力範圍。

可薩成為強權之後,東羅馬人也立即開始與他們結成同盟。695年,東羅馬希拉克略王朝的最後一位皇帝查士丁尼二世在被殘廢和罷黜後被放逐到克里米亞的克森尼索,此地由一個可薩官員(吐屯)管理。他在704或705年逃到了可薩汗國的領土,並受到可汗Busir的庇護,後者將妹妹嫁給了他,試圖重獲王位的查士丁尼可能認為這樁聯姻將讓他獲得強大的可薩汗國的支持[41]。查士丁尼二世隨即效仿查士丁尼一世,將其妻子也命改名為狄奧多拉(可薩的狄奧多拉)[42]。東羅馬的篡權者提比略三世賄賂了可汗,讓可汗殺死查士丁尼。受到西奧多拉的警告後,查士丁尼順利逃脫,途中還殺死了兩個可薩官員。他逃到了保加利亞,保加利亞汗幫助他重獲王位。隨後,儘管Busir此前背叛了他,但東羅馬和可薩的聯盟並沒有破裂,西奧多拉也被加冕為皇后[43][44]。

數十年之後,利奧三世(717–741在位)和可薩達成了一個類似的同盟以對抗共同的敵人穆斯林阿拉伯人。他派出密使前往可薩,讓兒子——後來的皇帝君士坦丁五世(741–775在位)與可汗比哈爾的女兒齊札克結婚,可汗的女兒皈依了基督教,並改名為伊琳娜(可薩的伊琳娜)。君士坦丁和伊琳娜育有一子,即後來的利奧四世,他也由此得名「可薩人利奧」[45][46]。到了8世紀,可薩人控制了克里米亞,甚至將其影響擴張至東羅馬屬地克森尼索半島,直到10世紀才撤回[47]。可薩和費爾干納的僱傭兵成為了一部分東羅馬皇家禁衛軍,這一職位可以通過支付7鎊黃金而購得[48][49]。

Remove ads

在7世紀和8世紀,可薩人與倭馬亞王朝及其繼承者阿拔斯王朝進行了一系列戰爭。第一次阿拉伯-可薩戰爭始於伊斯蘭教擴張的第一階段。640年穆斯林部隊已經到達亞美尼亞。642年,他們在Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah的領導下對高加索地區進行了首次突襲。652年,阿拉伯軍隊進攻可薩汗國首都巴倫加爾,但被擊敗且損失慘重;根據塔巴里等波斯歷史學家的說法,戰鬥中雙方都使用投石機對付敵方部隊。許多俄羅斯史料稱這一時期的可薩汗國的可汗名為埃爾比斯(Irbis),並將其描述為古突厥王室阿史那的繼承人。埃爾比斯是否曾存在,以及他是否就是許多同名的古突厥統治者之一,這些問題尚不明確。

由於第一次伊斯蘭內戰的爆發,阿拉伯人避免再次攻擊可薩人,直到8世紀初[50]。可薩人對穆斯林統治下的高加索諸公國進行了幾次襲擊,包括伊斯蘭教第二次內戰期間於683-685年進行的大規模進攻,由此獲得了很多戰利品和俘虜[51]。從塔巴里的記載中可以看出,可薩人與河中地區的古突厥殘餘勢力形成了統一戰線。

740年左右的高加索

第二次阿拉伯-可薩戰爭始於8世紀初期,高加索地區發生一系列襲擊。倭馬亞阿拉伯人鎮壓了一場大規模叛亂後在705年加強了對亞美尼亞的控制。在713或714年,倭馬亞將軍Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik征服了傑爾賓特,並進一步深入可薩汗國的領土。可薩人襲擊了高加索阿爾巴尼亞和伊朗阿塞拜疆,但被Hasan ibn al-Nu'man領導的阿拉伯人趕回[52]。軍事衝突在722年升級,3萬名可薩人入侵亞美尼亞,重創當地軍隊。哈里發耶齊德二世向北派遣了25,000名阿拉伯援軍,迅速將可薩人趕出高加索地區,恢復了傑爾賓特,並向巴蘭加爾前進。巴蘭加爾戰役中,阿拉伯人突破了可薩人防禦並衝進了這座城市,大多數居民被屠殺或淪為奴隸,但有少數設法逃往北方[51]。儘管取得了成功,但阿拉伯人尚未擊敗可薩軍隊,並撤退到了高加索南部。

724年,阿拉伯將軍al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami在庫拉河和阿拉斯河之間的漫長戰鬥中擊敗了可薩人,進而攻佔第比利斯,使高加索伊比利亞歸穆斯林所有。726年,可薩人在一位名叫巴爾吉克的王子的率領下發動反攻,對高加索阿爾巴尼亞和阿塞拜疆進行了大規模入侵。到729年,阿拉伯人失去了對外高加索東北部的控制,再次進入守勢。730年,巴爾吉克入侵伊朗阿塞拜疆,並在阿爾達比勒擊敗了阿拉伯軍隊(馬爾吉-阿爾達比勒戰役),殺死了Al-Djarrah al-Hakami將軍並短暫佔領了該地。第二年,巴爾吉克在摩蘇爾被擊敗並喪生。737年,Marwan Ibn Muhammad以尋求休戰為幌子進入可薩領土,然後發動了一次突襲,可汗逃往北方,可薩投降[53]。阿拉伯人沒有能力來影響外高加索地區的事務[53]。可汗被迫接受皈依伊斯蘭教的條件,並臣服於哈里發,但這一和解並未長久,由於倭馬亞內部的不穩定和拜占庭的支持,三年之內可薩人重獲獨立[54]。有人猜想可薩人早在740年就採納了猶太教,正是基於該歷史背景,即在作為面對哈里發和東羅馬時使用猶太教來確立其獨立性,同時也符合亞歐大陸居民普遍皈依一種世界性宗教的潮流[注 12]。

Remove ads

9世紀,瓦良格人已形成一個強大的軍-商系統,開始南下侵擾可薩人及其保護國(伏爾加保加利亞)控制下的水路,部分原因是為了經可薩-伏爾加保加利亞貿易區流向北方的阿拉伯白銀[注 13],另一部分原因則是皮毛和鐵製品貿易[注 14]。北方商隊行經阿的爾時,和行經東羅馬的赫爾松時一樣,會被收取什一稅[55]。斯拉夫人、伏爾加芬人和楚德人可能因此而聯合起來形成羅斯國家,來保護其自身利益免受可薩苛捐雜稅的影響。有人認為羅斯汗國的形成正是模仿了可薩汗國,瓦良格首領最早在830年就使用了「可汗」的稱號,這一稱號後來還繼續用來稱呼基輔羅斯的大公,而基輔羅斯首都基輔可能也是可薩建立的[56][57][注 15][注 16]。此外可薩從830年左右開始自主鑄幣,薩爾科勒堡壘的建造獲得了拜占庭的技術支持(拜占庭當時是可薩的盟國),這可能是為了抵禦北面的瓦良格人和東面草原的馬扎爾人[注 17][注 18]。到了860年,羅斯人已抵達基輔並通過第聶伯河到達君士坦丁堡[60]。

同盟關係經常發生變化。拜占庭受到瓦良格羅斯襲擊者威脅,會為可薩提供幫助,而可薩則時而允許北方人通過其領土以換取一部分戰利品[61]。從10世紀早期開始,由於附庸民族的起義以及前盟友的入侵加劇,可薩人常常多線戰鬥。草原上有佩切涅格人,北面則是實力不斷增強的羅斯人,兩者都不斷削弱可薩汗國的朝貢體系,可薩和平岌岌可危[62]。根據一位不知名的可薩人寫給一位身份不明的猶太人的書信,可薩統治者與一個五國聯合軍隊展開了戰鬥,這個聯合軍隊可能是受到拜占庭的慫恿[注 19]。儘管可薩取得了勝利,但他的兒子遭遇了又一輪入侵,這一次敵人是阿蘭人,阿蘭人首領皈依了基督教並與利奧五世的拜占庭結盟。

可薩原本控制第聶伯河中游並向那裏的東斯拉夫部落收取貢品;880年左右,隨着諾夫哥羅德的奧列格從瓦良格人手裏取得基輔,可薩對這一地區的控制減弱[63]。可薩人最初同意羅斯人沿着伏爾加河進行貿易並南下掠奪(見羅斯人的裏海遠征)。根據阿拉伯歷史學家馬蘇第的說法,可汗同意的條件是羅斯人給予他們一半的戰利品[61]。然而,913年,也就是拜占庭與羅斯達成和平協議兩年之後,在可薩的默許下,瓦良格人向阿拉伯人的領土進軍,導致花剌子模伊斯蘭衛隊向可薩統治者發出請求,要求允許他們對回程中的羅斯分遣隊進行反擊,目的是報復羅斯的劫掠給他們的穆斯林同胞造成的暴力傷害[注 20]。羅斯的軍隊遭遇徹底潰敗並被屠殺[61]。可薩統治者向羅斯人關閉了南下伏爾加的通道,由此引發了一場戰爭。960年,可薩統治者在一封信中提到了與羅斯關係的惡化:「我守衛河口,阻止乘船前來的羅斯人進入大海攻擊阿拉伯人,也阻止任何敵人走陸路進入傑爾賓特。」[注 21]。

羅斯軍閥向可薩汗國發動了多次戰爭,直搗裏海。一封書信中講述了一位HLGW(最近被確認為切爾尼戈夫的奧列格)攻擊可薩並被可薩將軍擊敗的故事[64]。可薩與東羅馬帝國的同盟在10世紀初期開始崩潰,兩者可能在克里米亞發生衝突,到了940年東羅馬皇帝君士坦丁七世在《帝國行政論》中思考了如何孤立並攻擊可薩。同期,拜占庭開始嘗試與佩切涅格人和羅斯結盟,並取得了不同程度的成功。斯維亞托斯拉夫一世最終在960年左右摧毀了可薩帝國的軍隊,並接觸了高加索地區的切爾克斯人[注 23],隨後又回到基輔[66]。首都阿的爾於公元968或969年左右陷落。

在羅斯編年史中,對可薩的征服與弗拉基米爾一世在986年的皈依有關[67]。根據《往年紀事》一書的記載,986年弗拉基米爾一世要決定基輔羅斯人信仰哪種宗教時,可薩猶太人也在場[68]。他們是已定居在基輔的猶太人,還是猶太可薩殘餘政權的密使,這一點不明確。接受一種「有經者」的宗教(即猶太教、基督教、伊斯蘭教)是與阿拉伯人達成任何和平協議的一條先決條件,此前阿拉伯人已派遣保加爾使節到達基輔[69]。

在阿的爾被洗劫後不久,一個到訪這座城市的旅客寫道,葡萄園和花園已被夷為平地,土地上沒有葡萄或葡萄乾,沒有東西可以施捨給窮人[70]。可能有人曾嘗試重建該城,因為後來有兩位穆斯林地理學家(Ibn Hawqal和al-Muqaddasi)都提到了這座城市,但在比魯尼時代(1048年),它已是一片廢墟[注 24]。

Remove ads

儘管Poliak認為可薩王國並沒有完全屈服於弗拉基米爾一世的軍事行動,而是一直維持到1224年蒙古征服基輔羅斯[71][72],大多數人認為,羅斯-烏古斯的聯合行動使可薩遭受了毀滅性的打擊,可能使大量可薩猶太人逃亡[73],充其量只有一個小殘存國家留下來。除了一些地名外,可薩幾乎沒有留下任何痕跡[注 25],其大部分人口無疑被後繼部落所吸收[74]。穆卡達西於985年左右寫到裏海以外的可薩是一個「禍患和骯髒」的地區,那裏有蜂蜜、許多綿羊和猶太人[75] 。東羅馬歷史學家克德雷諾斯提到1016年羅斯-拜占庭聯合進攻了可薩,擊敗了其首領Georgius Tzul(這一名字暗示他是基督教徒),這一歷史記錄總結道,在Georgius Tzul被擊敗之後,可薩統治者不得不請求和平與臣服[76]。1024年,切爾尼戈夫的姆斯季斯拉夫(弗拉基米爾的一個兒子)企圖對基輔恢復一種「可薩式」的統治[66],率領一支包括「可薩人和卡索斯人(即切爾克斯人)」在內的軍隊向他的兄弟雅羅斯拉夫行進,被擊退。伊本·艾西爾提到公元1030年「庫爾德人在Faḍlūn the Kurd的帶領下對可薩發動突襲」,10,000名庫爾德士兵被後者擊敗,這被視為可薩殘存政權存在的證據,但俄羅斯東方學家巴托爾德認為這裏所說的可薩人實際上是格魯吉亞人或阿布哈茲人[77][78]。據傳,一位名叫切爾尼戈夫的奧列格的基輔大公曾於1079年被「可薩人」綁架,並被運往君士坦丁堡,儘管大多數學者認為這是指當時在本都地區佔主導地位的庫曼-欽察人或其他草原民族。切爾尼戈夫大公的兒子在1080年代征服了特穆塔拉干後,就給自己冠以「可薩人的執政官」之稱[66]。據說,1083年奧列格在其兄弟被可薩人的盟友庫曼人殺害後,對可薩人進行了報復。1106年與這些庫曼人再次發生衝突之後,可薩人從歷史上淡出[76]。到13世紀,他們的故事在俄國的民間傳說中只是作為「猶太人之鄉」里的「猶太英雄」而流傳下來[79]。

12世紀末,一位德國拉比雷根斯堡的佩塔基亞到訪了他稱之為「可薩利亞」的地方,除了描述他們不停哀悼、一片荒涼中的極簡(某個宗派)生活外,別無其他評論[80]。提到的宗派似乎是猶太教卡拉派[81]。方濟各會傳教士魯不魯乞在曾經是可薩首都所在地的伏爾加河下游只發現了貧困的牧場[82]。柏郎嘉賓時任羅馬教皇駐貴由朝廷的使節,他曾提到一個未經證實的猶太部落,布魯塔基,可能在伏爾加河地區;儘管人們把這一部落與可薩人聯繫了起來,但唯一的關係僅僅是猶太教的歸屬[83]。

十世紀的瑣羅亞斯德教著作登卡德記錄了可薩政權的衰落,並將其歸因於「假」宗教對可薩力量的削弱[注 26]。可薩的衰落與東方河中地區薩曼王朝的衰落是同時代的,兩個事件都為塞爾柱帝國的崛起鋪平了道路,而塞爾柱帝國的崛起傳統都提到了可薩人的聯繫 [84][注 27]。繼承政權都不再能抵禦東方和南方游牧民族擴張的壓力。到了1043年, 基馬克部落和欽察部落向西挺進,給烏古斯人帶來壓力,烏古斯人又將佩切涅格人向西推向拜占庭的巴爾幹省份[85]。

儘管如此,可薩利亞還是給新興國家以及一些傳統和制度上留下了自己的印記。更早之前,利奧三世的可薩妻子將可薩人獨特的卡夫坦長袍和騎馬習慣引入了東羅馬宮廷,並作為一些莊重的元素用於帝國服飾中[注 28]。此外,基輔羅斯有序的繼承等級體系可以說是通過羅斯汗國而沿襲自可薩汗國[86]。

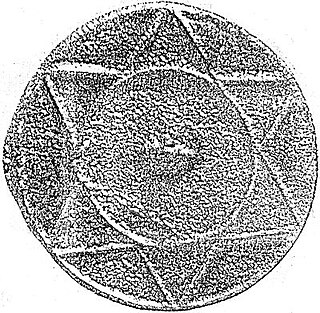

本都地區的原始匈牙利(馬扎爾人)部落雖然可能早在839年就威脅了可薩,但仍實行自己的體制模式,例如kende-kündü和gyula分別管理實際事務和軍事事務的雙重統治體系,同時成為可薩人的朝貢國。可薩汗國的異見團體卡巴爾人與馬扎爾人一起向西遷移到潘諾尼亞。匈牙利的部分人口可以看作是延續可薩傳統的繼承者。拜占庭曾稱匈牙利為西圖爾基亞,與東部的圖爾基亞——即可薩利亞相對。阿爾帕德大公的後裔里產生了中世紀的匈牙利國王,而卡巴爾人則保留了更長的傳統,且被稱為「黑馬扎爾人」(fekete magyarság)。塞爾維亞小鎮Čelarevo的一些考古學證據表明卡巴爾人信奉猶太教[87][88][89],因為士兵墳墓里發現了帶有猶太符號的文物,如猶太教燈臺、羊角號(猶太教徒禮拜時用的)、香櫞果(一種檸檬)、棕櫚枝、熄燭罩、集塵器、希伯來語銘文和一個大衛之星相同的六芒星[90][91]。

可薩汗國不是從第二聖殿被毀(67–70年)到以色列建立(1948年)之間唯一存在過的一個猶太國家。希木葉爾王國也曾於4世紀接受猶太教,直到伊斯蘭教興起[92]。

可薩汗國早在猶大·哈列維的時代就曾激發猶太人重返以色列的彌賽亞願望[93]。12世紀初期的埃及,一個名叫Solomon ben Duji,通常被認為是可薩猶太人[注 30],試圖倡導猶太人的解放並呼籲所有猶太人重回巴勒斯坦,寫信給許多猶太人社區爭取支持。他最終移居庫爾德斯坦。幾十年後他的兒子梅納赫姆自稱彌賽亞,為此組建了一支軍隊,佔領了摩蘇爾以北的阿馬迪耶堡壘。他的計劃遭到拉比權威的反對,在睡眠中被毒死。有一種理論認為,當時還只是裝飾圖案或魔法紋章的大衛之星,就從梅納赫姆的使用之後,開始在猶太晚期傳統文化中成為民族價值的象徵。

「可薩」一詞作為民族名最後被使用是13世紀北高加索的一個信仰猶太教的民族[94]。可薩流散社區的性質(猶太教或者其他宗教)還存在爭議。Avraham ibn Daud提到他在1160年左右遇見過來自西班牙托萊多的可薩裔拉比學生[95]。可薩社會在不同地方繼續存在。許多可薩僱傭兵進入了伊斯蘭哈里發和其他國家的軍隊。中世紀君士坦丁堡的文獻裏表明了加拉塔郊區可薩社區與猶太人混居的情況[96]。可薩商人活躍於12世紀的君士坦丁堡和亞歷山大港[97]。

一些信奉猶太教的可薩人可能加入了中歐猶太社區。許多講突厥語的猶太民族的代表,如卡拉伊姆人和克里姆查克人,認為自己是可薩人的後裔。北高加索的一些民族,特別是庫梅克人,可能有可薩人的根源。

可薩人也是哈薩克族族源之一。

Remove ads

宗教

格魯吉亞的阿拉伯聖徒第比利斯的阿波於779-780左右在可薩王國境內皈依了基督教,他將本地可薩人描述為無宗教[注 31]。一些史料則稱薩曼達爾大多數居民是基督徒[注 32],也有史料說大多數人是穆斯林[注 33]。

可薩人皈依猶太教的事件,既有外部史料的記錄,又可見於可薩書信,儘管也存在一些疑點[99]。希伯來文本的真實性曾長期受到質疑[注 34],但現在專家們普遍認為它們要麼是真實的,要麼反映了可薩內部文化傳統[注 35][注 36][注 37][101]。另一方面,關於皈依的考古學證據則依然難以捉摸[注 38][注 39],可能反映考古挖掘不夠完整,或者說明真正皈依猶太教的階層很少[注 40]。草原部落皈依某個普世宗教是一個得到了很好證實的現象[注 41],可薩皈依猶太人,雖然比較反常,但也不應該是罕見的[注 42]。其他學者則斷言可薩精英統治階層皈依猶太教一事從未發生過;一些學者[注 43]對皈依的故事不屑一顧,認為其只是傳說[99][104]。

據史料,來自伊斯蘭世界和東羅馬帝國的猶太人曾移民至可薩,以逃脫希拉克略、查士丁尼二世、利奧三世和羅曼努斯一世時期的宗教迫害[105][106]。英國歷史學家西蒙·沙瑪認為,在這些宗教迫害之後,巴爾幹半島和克里米亞等地,特別是希臘潘提卡彭的猶太社區,遷至宗教更為寬容的可薩,加入那裏的亞美尼亞猶太社區。他認為,開羅藏經庫殘篇清楚地表明,猶太化的改革扎根於整個可薩人口[107]。皈依的模式是一位精英階層首先接受新宗教隨後民眾大規模接受該宗教,民眾對於強迫改宗往往是抗拒的[108]。大規模改宗的一個重要條件是定居的、城市化的國家,在城市裏基督教堂、猶太會堂和清真寺提供了宗教中心,這和開放的大草原上自由的游牧生活方式相悖[注 44]。伊朗的高加索猶太人的一個傳說聲稱他們的祖先使可薩人皈依了猶太教[109]。可追溯到16世紀意大利拉比Judah Moscato的一個傳說則將其歸功於Yitzhak ha-Sangari[110][111][112]。

皈依的時間和精英階層以外的影響程度[注 45],後者不受一些學者的重視[注 46],這兩點都還很有爭議[注 47],但在740年到920年之間的某個時候,可薩皇家和貴族家庭似乎皈依了猶太教,部分原因可能是為了轉移阿拉伯人和東羅馬人要求他們皈依伊斯蘭教或基督教的壓力[注 48][注 49]。

在八世紀中葉,可薩王公從薩滿教皈依猶太教(具體是卡拉派猶太教)。大約740年可薩可汗信奉猶太教,由一名有猶太人血統的將軍布藍倡導下接受(成為國教),一部分平民跟進,但平民多是穆斯林與基督徒。

十世紀時阿拉伯人說他們已與猶太人無異。在十一世紀受基輔羅斯人,東羅馬帝國與佩切涅格人攻擊下覆滅,現在的克里米亞從前稱可薩利亞,很多民族稱呼裏海為可薩海。勢力最大時至摩蘇爾。

965年,伊斯蘭歷史學家伊本·阿希爾提到,受到烏古斯人攻擊的可薩人向花剌子模求援,但因為他們在花剌子模眼中是「卡菲勒」,故遭到拒絕;據說可薩人因而皈依了伊斯蘭教,於是,花剌子模軍事協助可薩人驅逐了烏古斯人(由稱為艾爾西亞的傭兵協助)。根據伊本·阿希爾的說法,這件事使得可薩的猶太國王皈依了伊斯蘭教[69]

伊本·法德蘭特別講述了一起事件,其中可薩國王摧毀了阿的爾一座清真寺的尖塔,以報復對Dâr al-Bâbûnaj的一座猶太教堂的毀滅,並據稱他說,如果不是因為害怕穆斯林會對猶太人進行報復,他會做得更糟。

文化和制度

可薩人是歐洲突厥語部落中最文明的,他們曾有三個首都:

統治階層是一群人數相對較少、民族和語言不同於被統治者的團體,被統治者主要有阿蘭人和烏古爾突厥部落,他們在人數上超過可薩人[113]。可薩的可汗從被統治民族裏娶妻納妾,伊本·法德蘭說可汗有25位妻子60個妾,宮廷也有閹人,這種做法影響了後來的匈牙利人與烏古斯人;可汗受到花剌子模禁衛軍(稱為艾爾西亞)的貼身保護[注 50][注 51]。但與這一地區其他政體不同的是,他們招募僱傭兵(被阿拉伯歷史學家馬蘇第稱為junûd murtazîqa)[114]。在帝國的頂峰時期,可薩人實行集中的財政管理,常備部隊大約有7000-12000名士兵,在有必要時,可以從貴族的隨員里招募儲備兵,使其人數增至兩倍或三倍[115][注 52]。關於常備部隊的其他數字可多達10萬。 他們控制着25至30個不同的民族和部落,並要求他們進貢,這些部落居住在高加索、鹹海、烏拉爾山脈和烏克蘭草原之間的廣闊領土上[116],對內自治,對可薩納貢,可薩將他們的統治者封為俟利發。可薩軍隊由汗伯克(Qağan Bek)領導,並由稱為答剌罕的下屬軍官指揮。當汗伯克派出一支部隊時,他們無論如何都不會撤退;如果被擊敗,每一個返回的人都會被殺死[117]。

定居區由稱為吐屯的行政官員管理。在某些情況下,例如克里米亞南部的拜占庭城鎮,通常會在另一政權的勢力範圍內為一個城鎮委派一個名義上的吐屯。

據估計可薩汗國的人口除了統治者以外共有25到28個不同的族群。精英統治階層則似乎是由9個部落/氏族組成,他們內部的民族成份也不是單一的,可能分別統治9個省份或公國[118]。至於種姓或階級,有證據表明存在「黑可薩人」(ak-Khazars)和「白可薩人」(qara-Khazars)的區別,但該區別是種族層面的還是社會層面的並不明確[118]。10世紀的穆斯林地理學家伊斯塔克里提出白可薩人十分俊美,他們白膚、紅髮、藍眼珠,而黑可薩人則皮膚黑黝黝的接近深黑,好像他們是「某種形式的印度人」[119]。許多突厥語國家也有類似的(政治層面的,而不是種族層面的)區分,「白色」的占統治地位的武士種姓和「黑色」的平民階層。主流學者的普遍意見是伊斯塔克里錯誤理解了給這個群體的名稱[120]。早期阿拉伯史料普遍把可薩人描述為白膚、藍眸和紅髮[121][122]。唐朝典籍里通常被視為可薩統治階層的「阿史那」可能是來自東伊朗語或吐火羅語里表示「藍色」或「深色」的詞——塞語:âşşeina-āššsena(藍);中古波斯語:axšaêna(深色的);吐火羅語:Aâśna(藍色或深色)[123]。可薩帝國崩潰之後,這一區分似乎依然存在。後來的羅斯編年史在描述可薩人在匈牙利的馬扎爾化過程中扮演的角色時,將可薩人稱為「白烏古爾」,將馬扎爾人稱為「黑烏古爾」[124]。對遺體(如頭骨)的研究顯示斯拉夫人、其他歐洲人和一些蒙古人的混合[120]。

外國商品的進出口以及對過境商品徵稅所產生的收入,是可薩經濟的主要特徵,不過據說可薩也生產了雲母[125]。在游牧草原政體中,可薩汗國獨特地發展了自給自足的Saltovo-Mayaki[126]經濟——傳統畜牧和廣泛農業的綜合體,一方面得以出口綿羊和牛,另一方面充分利用伏爾加河豐富的漁業資源,並進行手工藝品的製造,再加上因控制主要貿易路線而獲得的豐富的國際貿易稅收。可薩人還是穆斯林奴隸市場的兩個重要參與者之一(另一個是伊朗的薩曼王朝),他們向穆斯林提供來自歐亞北部地區被俘的斯拉夫人和部落民[127]。從奴隸交易里獲得的利益使可薩得以維持一支與花剌子模穆斯林軍隊對抗的常備部隊。可薩首都阿的爾反映了一種分裂:西岸的哈拉贊生活着國王及其統治精英,約有4,000名隨從;而東岸的伊蒂爾則居住着猶太人、基督教徒、穆斯林和奴隸以及手工藝者和外國商人[注 53]。執政精英在這座城市過冬,從春季到深秋則都在他們的田間度過。首都外的一片大型灌溉綠地,通過運河與伏爾加河的連接,那裏的草地和葡萄園延伸約20法拉赫(約60英里)[82]。一邊對商人徵收關稅,另一邊對25到30個部落收取貢品和什一稅,徵收貢品有:黑貂皮、松鼠皮,劍,或皮革、蠟、蜂蜜和牲畜,具體取決於地區。貿易糾紛由阿的爾的一個商業法庭處理,該法庭由七名法官組成,猶太教徒、穆斯林、基督教徒各兩名,還有一名異教徒[注 54]。

文學作品

諾貝爾文學獎獲得者、塞爾維亞米洛拉德·帕維奇作家所著《哈扎爾辭典》一書,以詞條釋義的形式,從基督教、猶太教和伊斯蘭教三種史料的角度講述可薩人的歷史,其中心主題就是可薩汗國大規模皈依的問題以及關於身份認同的真理的難確定性[128]。

註釋

- This figure has been calculated on the basis of the data in both Herlihy and Russell's work.[5] (Russell 1972,第25–71頁)

- "The Gazari are, presumably, the Khazars, although this term or the Kozary of the perhaps near contemporary Vita Constantini ... could have reflected any of a number of peoples within Khazaria." (Golden 2007b,第139頁)

- "Somewhat later, however, in a letter to the Byzantine Emperor Basil I, dated to 871, Louis the German, clearly taking exception to what had apparently become Byzantine usage, declares that 'we have not found that the leader of the Avars, or Khazars (Gasanorum)'..." (Golden 2001a,第33頁)

- "The word tribe is as troublesome as the term clan. It is commonly held to denote a group, like the clan, claiming descent from a common (in some culture zones eponymous) ancestor, possessing a common territory, economy, language, culture, religion, and sense of identity. In reality, tribes were often highly fluid sociopolitical structures, arising as 'ad hoc responses to ephemeral situations of competition,' as Morton H. Fried has noted." (Golden 2001b,第78頁)

- Dieter Ludwig, in his doctoral thesis Struktur und Gesellschaft des Chazaren-Reiches im Licht der schriftlichen Quellen, (Münster, 1982) suggested that the Khazars were Turkic members of the Hephthalite Empire, where the lingua franca was a variety of Iranian.[20] (Brook 2010,第4頁)

- "The reader should be warned that the A-shih-na link of the Khazar dynasty, an old phantom of ... Khazarology, will ... lose its last claim to reality". (Zuckerman 2007,第404頁)

- In this view, the name Khazar would derive from a hypothetical *Aq Qasar. (Golden 2006,第89–90頁)

- The Duōlù (咄陸) were the left wing of the On Oq, the Nǔshībì (弩失畢: *Nu Šad(a)pit), and together they were registered in Chinese sources as the 'ten names' (shí míng:十名). (Golden 2010,第54–55頁)

- Theophanes the Confessor around 813 defined them as Eastern Turks. The designation is complex and Róna-Tas writes: "The Georgian Chronicle refers to the Khazars in 626–628 as the 'West Turks' who were then opposed to the East Turks of Central Asia. Shortly after 679 the Armenian Geography mentions the Turks together with the Khazars; this may be the first record of the Magyars. Around 813, Theophanes uses – alongside the generic name Turk – 'East Turk' for the designation of the Khazars, and in context, the 'West Turks' may actually have meant the Magyars. We know that Nicholas Misticus referred to the Magyars as 'West Turks' in 924/925. In the 9th century the name Turk was mainly used to designate the Khazars." (Róna-Tas 1999,第282頁)

- Many sources identify the Göktürks in this alliance as Khazars--for example, Beckwith writes recently: "The alliance sealed by Heraclius with the Khazars in 627 was of seminal importance to the Byzantine Empire through the Early Middle Ages, and helped assure its long-term survival."[37]Early sources such as the almost contemporary Armenian history, Patmutʿiwn Ałuanicʿ Ašxarhi, attributed to Movsēs Dasxurancʿ, and the Chronicle attributed to Theophanes identify these Turks as Khazars (Theophanes has: 'Turks, who are called Khazars'). Both Zuckerman and Golden reject the identification. (Zuckerman 2007,第403–404頁)

- Scholars dismiss Chinese annals which, reporting the events from Turkic sources, attribute the destruction of Persia and its leader Shah Khusrau II personally to Tong Yabghu. Zuckerman argues instead that the account is correct in its essentials. (Zuckerman 2007,第417頁)

- "The Khazars, the close allies of the Byzantines, adopted Judaism, as their official religion, apparently by 740, three years after an invasion by the Arabs under Marwan ibn Muhammad. Marwan had used treachery against a Khazar envoy to gain peaceful entrance to Khazar territory. He then declared his dishonourable intentions and pressed deep into Khazar territory, only subsequently releasing the envoy. The Arabs devastated the horse herds, seized many Khazars and others as captives, and forced much of the population to flee into the Ural Mountains. Marwan's terms were that the kaghan and his Khazars should convert to Islam. Having no choice, the kaghan agreed, and the Arabs returned home in triumph. As soon as the Arabs were gone, the kaghan renounced Islam – with, one may assume, great vehemence. The Khazar Dynasty's conversion to Judaism is best explained by this specific historical background, together with the fact that the mid-eighth century was an age in which the major Eurasian states proclaimed their adherence to distinctive world religions. Adopting Judaism also was politically astute: it meant the Khazars avoided having to accept the overlordship (however theoretical) of the Arab caliph or the Byzantine emperor." (Beckwith 2011,第149頁)

- The Volga Bulgarian state was converted to Islam in the 10th century, and wrested liberty from its Khazarian suzerains when Sviatoslav I of Kiev|Svyatislav razed Atil. (Abulafia 1987,第419, 480–483頁)

- Whittow argues however that: "The title of qaghan, with its claims to lordship over the steppe world, is likely to be no more than ideological booty from the 965 victory." (Whittow 1996,第243–252頁)

- Korobkin citing Golb & Pritsak notes that Khazars have often been connected with Kiev's foundations.[58] Pritsak and Golb state that children in Kiev were being given a mixture of Hebrew and Slavic languages names by c. 930.[59] Toch on the other hand is skeptical, and argues that "a significant Jewish presence in early medieval Kiev or indeed in Russia at large remains much in doubt". (Toch 2012,第166頁)

- The yarmaq based on the Arab dirhem was perhaps issued in reaction to fall-off in Muslim minting in the 820s, and to a felt need in the turbulent upheavals of the 830s to assert a new religious profile, with the Jewish legends stamped on them. (Golden 2007b,第156頁)

- Scholars are divided as to whether the fortification of Sarkel represents a defensive bulwark against a growing Magyar or Varangian threat. (Petrukhin 2007,第247, and n.1頁)

- MQDWN or the Macedonian dynasty of Byzantium; SY, perhaps a central Volga statelet, Burtas, Asya; PYYNYL denoting the Danube-Don Pechnegs; BM, perhaps indicating the Volga Bulgars, and TWRQY or Oghuz Turks. The provisory identifications are those of Pritsak. (Kohen 2007,第106頁)

- Al-Mas'udi says the king secretly tipped off the Rus' of the attack but was unable to oppose the request of his guards. (Olsson 2013,第507頁)

- The letter continues: "I wage war with them. If I left them (in peace) for a single hour they would crush the whole land of the Ishmaelites up to Baghdad." (Petrukhin 2007,第257頁)

- From Klavdiy Lebedev (1852–1916), Svyatoslav's meeting with Emperor John I Tzimisces, as described by Leo the Deacon.

- Dunlop thought the later city of Saqsin lay on or near Atil. (Dunlop 1954,第248頁)

- The Caspian Sea is still known to Arabs, and many peoples of the region, as the 'Khazar Sea' (Arabic Bahr ul-Khazar) (Brook 2010,第156頁)

- "thus it is clear that the false doctrine of Yišô in Rome (Hrôm) and that of Môsê among the Khazars and that of Mânî in Turkistan took away their might and the valor that they once possessed and made them feeble and decadent among their rivals". (Golden 2007b,第130頁)

- Some sources claim that the father of Seljuk (warlord), the eponymous progenitor of the Seljuk Turks, namely Toqaq Temür Yalığ, began his career as an Oghuz soldier in Khazar service in the early and mid-10th century, and rose to high rank before he fell out with the Khazar rulers and departed for Khwarazm. Seljuk's sons, significantly, all bear names from the Tanakh|Jewish scriptures: Mîkâ'il, Isrâ'îl, Mûsâ, Yûnus. Peacock argues that early traditions attesting a Seljuk origin within the Khazar empire when it was powerful, were later rewritten, after Khazaria fell from power in the 11th century, to blank out the connection. (Peacock 2010,第27–35頁)

- Tzitzak is often treated as her original proper name, with a Turkic etymology čiček ('flower'). Erdal, however, citing the Byzantine work on court ceremony De Ceremoniis, authored by Constantine Porphyrogennetos, argues that the word referred only to the dress Irene wore at court, perhaps denoting its colourfulness, and compares it to the Hebrew Tzitzit

- "Engravings that resemble the six-pointed Star of David were found on circular Khazar relics and bronze mirrors from Sarkel and Khazarian grave fields in Upper Saltov. However, rather than having been made by Jews, these appear to be shamanistic sun discs." (Brook 2010,第113, 122–123 n.148頁)

- Brook says this thesis was developed by Jacob Mann, based on a reading of the word "Khazaria" in the Cairo Geniza fragment. Bernard Lewis, he adds, challenged the assumption by noting that the original text reads Hakkâri and refers to the Kurds of the Hakkâri mountains in south-east Turkey. (Brook 2010,第191–192, n.72頁)

- Golden and Shapira thinks the evidence from such Georgian sources renders suspect a conversion prior to this date.[98](Shapira 2007b,第347–348頁)

- Golden 2007b,第135–136頁, reporting on al-Muqaddasi.

- During Islamic invasions, some groups of Khazars who suffered defeat, including a qağan, were converted to Islam. (DeWeese 1994,第73頁)

- Johannes Buxtorf first published the letters around 1660. Controversy arose over their authenticity; it was even argued that the letters represented "no more than Jewish self-consolation and fantasmagory over the lost dreams of statehood". (Kohen 2007,第112頁)

- "If anyone thinks that the Khazar correspondence was first composed in 1577 and published in Qol Mebasser, the onus of proof is certainly on him. He must show that a number of ancient manuscripts, which appear to contain references to the correspondence, have all been interpolated since the end of the sixteenth century. This will prove a very difficult or rather an impossible task." (Dunlop 1954,第130頁)

- "The issue of the authenticity of the Correspondence has a long and mottled history which need not detain us here. Dunlop and most recently Golb have demonstrated that Hasdai's letter, Joseph's response (dating perhaps from the 950s) and the 'Cambridge Document' are, indeed, authentic." (Golden 2007b,第145–146頁)

- "(a court debate on conversion) appears in accounts of Khazar Judaism in two Hebrew accounts, as well as in one eleventh-century Arabic account. These widespread and evidently independent attestations would seem to support the historicity of some kind of court debate, but, more important, clearly suggest the currency of tales recounting the conversion and originating among the Khazar Jewish community itself" ... "the 'authenticity' of the Khazar correspondence is hardly relevant"[100] "The wider issue of the 'authenticity' of the 'Khazar correspondence', and of the significance of this tale's parallels with the equally controversial Cambridge document /Schechter text, has been discussed extensively in the literature on Khazar Judaism; much of the debate loses significance if, as Pritsak has recently suggested, the accounts are approached as 'epic' narratives rather than evaluated from the standpoint of their 'historicity'." (DeWeese 1994,第305頁)

- Shingiray noting the widespread lack of artifacts of wealth in Khazar burials, arguing that nomads used few materials to express their personal attributes: "The SMC assemblages-even if they were not entirely missing from the Khazar imperial center - presented an outstanding instance of archaeological material minimalism in this region." (Shingiray 2012,第209–211頁)

- "But, one must ask, are we to expect much religious paraphernalia in a recently converted steppe society? Do the Oğuz, in the century or so after their Islamization, present much physical evidence in the steppe for their new faith? These conclusions must be considered preliminary." (Golden 2007b,第150–151, and note 137頁)

- Golden 2007b,第128–129頁 compares Ulfilas's conversions of the Goths to Arianism; Al-Masudi records a conversion of the Alans to Christianity during the Abbasid period; the Volga Bulğars adopted Islam after their leader converted in the 10th century; the Uyğur Qağan accepted Manichaeism in 762.

- Golden takes exception to J. B. Bury's claim (1912) that it was 'unique in history'.[102][103] Golden also cites from Jewish history the conversion of Idumeans under John Hyrcanus; of the Itureans under Aristobulus I; of the kingdom of Adiabene under Queen Helena; the Ḥimyârî kings in Yemen, and Berber assimilations to North African Jewry. (Golden 2007b,第153頁)

- "in Israel, emotions are still high when it comes to the history of the Khazars, as I witnessed in a symposium on the issue at the Israeli Academy of Sciences in Jerusalem (May 24, 2011). Whereas Prof. Shaul Stampfer believed the story of the Khazars' conversion to Judaism was a collection of stories or legends that have no historical foundation, (and insisted that the Ashkenazi of Eastern Europe of today stem from Jews in Central Europe who emigrated eastwards), Prof. Dan Shapiro believed that the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism was part of the history of Russia at the time it established itself as a kingdom." (Falk 2017,第101,n.9頁)

- "The Șûfî wandering out into the steppe was far more effective in bringing Islam to the Turkic nomads than the learned 'ulamâ of the cities." (Golden 2007b,第126頁)

- "the Khazars (most of whom did not convert to Judaism, but remained animists, or adopted Islam and Christianity)" (Wexler 2002,第514頁)

- "In much of the literature on conversions of Inner Asian peoples, attempts are made, 'to minimize the impact' ... This has certainly been true of some of the scholarship regarding the Khazars." (Golden 2007b,第127頁)

- "scholars who have contributed to the subject of the Khazars' conversion, have based their arguments on a limited corpus of textual, and more recently, numismatic evidence ... Taken together these sources offer a cacophony of distortions, contradictions, vested interests, and anomalies in some areas, and nothing but silence in others." (Olsson 2013,第496頁)

- "Judaism was apparently chosen because it was a religion of the book without being the faith of a neighbouring state which had designs on Khazar lands." (Noonan 1999,第502頁)

- "Their conversion to Judaism was the equivalent of a declaration of neutrality between the two rival powers." (Baron 1957,第198頁)

- This regiment was exempt from campaigning against fellow Muslims, evidence that non-Judaic beliefs were no obstacle to access to the highest levels of government. They had abandoned their homeland and sought service with the Khazars in exchange for the right to exercise their religious freedom, according to al-Masudi. (Golden 2007b,第138頁)

- Olsson writes that there is no evidence for this Islamic guard for the 9th century, but that its existence is attested for 913. (Olsson 2013,第507頁)

- Noonan gives the lower figure for the Muslim contingents, but adds that the army could draw on other mercenaries stationed in the capital, Rūs, Ṣaqāliba and pagans. Olsson's 10,000 refers to the spring-summer horsemen in the nomadic king's retinue. (Noonan 2007,第211, 217頁)

- A third division may have contained the dwellings of the tsarina. The dimensions of the western part were 3x3, as opposed to the eastern part's 8 x 8 farsakhs. (Noonan 2007,第208–209, 216–219頁)

- Outside Muslim traders were under the jurisdiction of a special royal official (ghulām). (Noonan 2007,第211–214頁)

參考資料

參見

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads