Around the World in Eighty Days

1872 novel written by Jules Verne From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Around the World in Eighty Days (French: Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours) is an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate the world in 80 days on a wager of £20,000 (equivalent to £2.3 million in 2023) set by his friends at the Reform Club. It is one of Verne's most acclaimed works.[4]

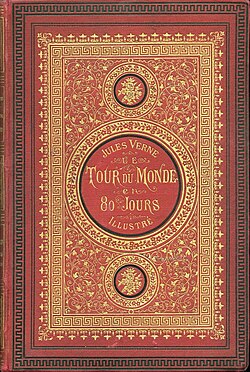

First Book Cover 1873 | |

| Author | Jules Verne |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours |

| Illustrator | Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville and Léon Benett[1] |

| Language | French |

| Series | The Extraordinary Voyages #11 |

| Genre | Adventure novel |

| Publisher | Le Temps (as serial)[2] Pierre-Jules Hetzel (book form) |

Publication date | 1872[2] (as serial) 30 January 1873[3] |

| Publication place | France |

Published in English | 1873 |

| Preceded by | The Fur Country |

| Followed by | The Mysterious Island |

| Text | Around the World in Eighty Days at Wikisource |

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Phileas Fogg is a wealthy English gentleman living a solitary life in London. Despite his wealth, Fogg lives modestly and carries out his habits with mathematical precision. He is a member of the Reform Club, where he spends a large portion of his days and nights. On the morning of 2 October 1872, having dismissed his valet for bringing him shaving water at a temperature slightly lower than expected, Fogg hires Frenchman Jean Passepartout as a replacement.

That evening, while at the Club, Fogg gets involved in a discussion regarding an article in The Morning Chronicle (or The Daily Telegraph in some editions) stating that with the opening of a new railway section in India, it is now possible to travel around the world in 80 days. He accepts a wager for £20,000, half of his fortune, from his fellow club members to complete such a journey within this period. With Passepartout accompanying him, Fogg departs from London by train at 8:45 p.m.; to win the wager, he must return to the club by this same time on 21 December, 80 days later. They take Fogg's remaining £20,000 with them to cover expenses during the journey.

| London to Suez, Egypt | Rail to Brindisi, Italy, via Turin and steamer (the Mongolia) across the Mediterranean Sea | 7 days |

| Suez to Bombay, India | Steamer (the Mongolia) across the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean | 13 days |

| Bombay to Calcutta, India | Rail | 3 days |

| Calcutta to Victoria, Hong Kong with a stopover in Singapore | Steamer (the Rangoon) across the South China Sea | 13 days |

| Hong Kong to Yokohama, Japan | Steamer (the Carnatic) across the South China Sea, East China Sea, and the Pacific Ocean | 6 days |

| Yokohama to San Francisco, USA | Steamer (the General Grant) across the Pacific Ocean | 22 days |

| San Francisco to New York City, USA | Rail | 7 days |

| New York to London, England (UK) | Steamer (the China) across the Atlantic Ocean to Liverpool and rail | 9 days |

| Total | 80 days | |

| ||

Fogg and Passepartout reach Suez on time. While disembarking in Egypt, they are watched by a Scotland Yard policeman, Detective Fix, who has been dispatched from London in search of James Strand, a bank robber. Since Fogg fits the vague description Scotland Yard was given of Strand, Detective Fix mistakes Fogg for the criminal. Since he cannot secure a warrant in time, Fix boards the steamer (the Mongolia) conveying the travellers to Bombay. Fix becomes acquainted with Passepartout without revealing his purpose. Fogg promises the steamer engineer a large reward if he gets them to Bombay early. They arrive in Bombay on 20 October, two days ahead of schedule, and board a train heading towards Calcutta that evening.

The early arrival in Bombay proves beneficial for Fogg and Passepartout, as contrary to what the newspaper article had said, an 80 km (50 mi) stretch of track from Kholby to Allahabad has not yet been built. Fogg purchases an elephant, hires a guide and starts toward Allahabad.

They come across a procession in which a young Indian woman, Aouda, is to undergo sati. Since she is drugged with opium and hashish and is not going voluntarily, the travellers decide to rescue her. They follow the procession to the site, where Passepartout takes the place of her deceased husband on the funeral pyre. He rises from the pyre during the ceremony, scaring off the priests and carries Aouda away. The two days gained earlier are lost but Fogg shows no regret.

Fogg and Passepartout re-board the train at Allahabad, taking Aouda with them. When the travelers arrive in Calcutta, Fix, who had arrived ahead of them, has Fogg and Passepartout arrested for a crime Passepartout had committed in Bombay. They jump bail and board a steamer (the Rangoon) going to Hong Kong, with a day's stopover in Singapore. Fix also boards the Rangoon; he shows himself to Passepartout, who is delighted to again meet his friend from the earlier voyage.

In Hong Kong, the group learns Aouda's distant relative, in whose care they had been planning to leave her, has moved to Holland, so they decide to take her with them to Europe. Still without a warrant, Fix sees Hong Kong as his last chance to arrest Fogg on British soil. Passepartout becomes convinced that Fix is a spy from the Reform Club. Fix confides in Passepartout, who does not believe a word and remains convinced that his master is not a robber. To prevent Passepartout from informing his master about the premature departure of their next vessel, the Carnatic, Fix gets Passepartout drunk and drugs him in an opium den. Passepartout still manages to catch the steamer to Yokohama but cannot inform Fogg that the steamer is leaving the evening before its scheduled departure date.

Fogg discovers he missed his connection. He searches for a vessel that will take him to Yokohama, finding a pilot boat, the Tankadere, that takes him, Aouda, and Fix to Shanghai, where they catch a steamer to Yokohama. There, they search for Passepartout, believing he arrived on the Carnatic as initially planned. They find him in a circus, trying to earn the fare for his homeward journey. Reunited, the four board a paddle-steamer, the General Grant, taking them across the Pacific to San Francisco. Fix promises Passepartout that now, having left British soil, he will no longer try to delay Fogg's journey but instead support him in getting back to Britain, where he can arrest him.

In San Francisco, they board a transcontinental train to New York City, encountering several obstacles along the way: a herd of bison crossing the tracks, a failing suspension bridge and a band of Sioux warriors ambushing the train. After uncoupling the locomotive from the carriages, Passepartout is kidnapped by the warriors. Fogg rescues him after American soldiers volunteer to help. They continue by a wind-powered sled to Omaha and then get a train to New York.

In New York, having missed the ship China, Fogg looks for alternative transport. He finds a steamboat, Henrietta, destined for Bordeaux, France. The captain of the boat refuses to take them to Liverpool, whereupon Fogg consents to be taken to Bordeaux for $2,000 per passenger. He then bribes the crew to mutiny and makes course for Liverpool. Against hurricane winds and going on full steam, the boat runs out of fuel after a few days. When the coal runs out, Fogg buys the boat from the captain, then has the crew burn all the wooden parts to keep up the steam.

The companions arrive at Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland, take the train to Dublin and then a ferry to Liverpool, still in time to reach London before the deadline. Once on English soil, Fix arrests Fogg. A short time later, the misunderstanding is cleared up – the actual robber had been caught three days earlier in Edinburgh. As a result of the delay, Fogg misses the scheduled train to London; he orders a special train and arrives in London apparently five minutes late, certain he has lost the wager.

The following day Fogg apologises to Aouda for bringing her with him since he now has to live in poverty and cannot support her. Aouda confesses that she loves him and asks him to marry her. As Passepartout notifies a minister, he learns that he is mistaken in the date – it is not 22 December, but instead 21 December. Because the party had travelled eastward, their days were shortened by four minutes for every degree of longitude they crossed; thus, although they had experienced the same amount of time abroad as people had experienced in London, they had seen 80 sunrises and sunsets while London had seen only 79. Passepartout informs Fogg of his mistake and Fogg hurries to the Club just in time to meet his deadline and win the wager. Having spent almost £19,000 of his travel money during the journey, he divides the remainder between Passepartout and Fix and marries Aouda.

Background and analysis

Summarize

Perspective

Around the World in Eighty Days was written during difficult times, both for France and Verne. It was during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) in which Verne was conscripted as a coastguard; he was having financial difficulties (his previous works were not paid royalties); his father had died recently; and he had witnessed a public execution, which disturbed him.[6]

The technological innovations of the 19th century had opened the possibility of rapid circumnavigation, and the prospect fascinated Verne and his readership. In particular, three technological breakthroughs occurred in 1869–1870 that made a tourist-like around-the-world journey possible for the first time: the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in America (1869), the opening of the Suez Canal (1869), and the linking of the Indian railways across the sub-continent (1870). It was another notable mark at the end of an age of exploration and the start of an age of fully global tourism that could be enjoyed in relative comfort and safety. It sparked the imagination that anyone could sit down, draw up a schedule, buy tickets and travel around the world, a feat previously reserved for only the most heroic and hardy of adventurers.[6]

The story began serialization in Le Temps on 6 November 1872.[7] The story was published in installments over the next 45 days, with its ending timed to synchronize Fogg's December 21 deadline with the real world. Chapter XXXV appeared on 20 December;[8] 21 December, the date upon which Fogg was due to appear back in London, did not include an installment of the story;[9] on 22 December, the final two chapters announced Fogg's success.[10] As it was being published serially for the first time, some readers believed that the journey was actually taking place – bets were placed, and some railway companies and ship liner companies lobbied Verne to appear in the book. It is unknown if Verne submitted to their requests, but the descriptions of some rail and shipping lines leave some suspicion he was influenced.[6]

Concerning the final coup de théâtre, Fogg had thought it was one day later than it actually was because he had forgotten that during his journey, he had added a full day to his clock, at the rate of an hour per 15° of longitude crossed. At the time of publication and until 1884, a de jure International Date Line did not exist. If it did, he would have been made aware of the change in date once he reached this line. Thus, the day he added to his clock throughout his journey would be removed upon crossing this imaginary line. However, Fogg's mistake would not have been likely to occur in the real world because a de facto date line did exist. The UK, India, and the US had the same calendar with different local times. When he arrived in San Francisco, he would have noticed that the local date was one day earlier than shown in his travel diary. Consequently, it is unlikely he would fail to notice that the departure dates of the transcontinental train in San Francisco and of the China steamer in New York were one day earlier than his travel diary. He would also somehow have to avoid looking at any newspapers. Additionally, in Who Betrays Elizabeth Bennet?, John Sutherland points out that Fogg and company would have to be "deaf, dumb and blind" not to notice how busy the streets were on an apparent "Sunday", with the Sunday Observance Act 1780 still in effect.[11]

Real-life imitations

Summarize

Perspective

Following publication in 1873, various people attempted to follow Fogg's fictional circumnavigation, often within self-imposed constraints:

- In 1889, Nellie Bly undertook to travel around the world in 80 days for her newspaper, the New York World. She managed to do the journey within 72 days, meeting Verne in Amiens. Her book Around the World in Seventy-Two Days became a best seller.

- In 1889, Elizabeth Bisland working for the Cosmopolitan became a rival to Bly, racing her across the world to try to achieve the global crossing first.[12]

- In 1894, George Griffith carried out a publicity stunt on behalf of C. Arthur Pearson by circumnavigating the world in 65 days, from 12 March to 16 May.[13][14] The tale of his journey was told in Pearson's Weekly in 14 parts between 2 June and 1 September 1894, bearing the title "How I Broke the Record Round the World".[14][15] It was later published in book form in 2008 under the title Around the World in 65 Days.[15]

- In 1903, James Willis Sayre, an American theatre critic and arts promoter, set a world record for circling the earth using public transport: 54 days, 9 hours and 42 minutes.[16]

- In 1908, Harry Bensley, on a wager, set out to circumnavigate the world on foot wearing an iron mask. The journey was abandoned, incomplete, at the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[citation needed]

- In 1928, 15-year-old Danish Boy Scout Palle Huld travelled around the world by train and ship in the opposite direction to the one in the book. His trip was sponsored by a Danish newspaper and made on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Jules Verne. The trip was described in the book A Boy Scout Around the World. It took 44 days. He took the Trans-Siberian Railway and did not go by India.

- In 1984, Nicholas Coleridge emulated Fogg's trip, taking 78 days; he wrote a book titled Around the World in 78 Days.[17]

- In 1988, Monty Python member Michael Palin took on a similar challenge without using aircraft, as a part of a television travelogue, called Around the World in 80 Days with Michael Palin. He completed the journey in 79 days and 7 hours.

- Since 1993, the Jules Verne Trophy has been given to the boat that sails around the world without stopping and with no outside assistance in the shortest time.

- In 2009, twelve celebrities performed a relay version of the journey for the BBC Children in Need charity appeal.

- In 2011, Brazilian businessman and TV host Álvaro Garnero and journalist José Antonio Ramalho made a bet with a pub owner in London to travel around the world in 80 days. The Record (TV network) TV series "50 by 1 - Around the World in 80 Days" followed their journey. Both Brazilians crossed the Atlantic and Pacific, USA, Canada, Alaska, Japan, South Korea, China, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic nations, Scandinavia, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium and France to end again at the pub in 81 days (they arrived in London in 80 days but the pub was closed at night).

- In 2017, Mark Beaumont, a British cyclist inspired by Verne, set out to cycle across the world in 80 days. He completed the trip in 78 days, 14 hours and 40 minutes, after departing from Paris on 2 July 2017. Beaumont beat the previous world record of 123 days, set by Andrew Nicholson, by cycling 29,000 km (18,000 mi) across the globe visiting Russia, Mongolia, China, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, US and a number of countries in Europe.[18]

Origins

Summarize

Perspective

The idea of a trip around the world within a set period had clear external origins. It was popular before Verne published his book in 1873. Even the title Around the World in Eighty Days is not original. Several sources have been hypothesized as the origins of the story.[6]

Another early reference comes from the Italian traveler Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri. He wrote a book in 1699 that was translated into French: Voyage around the World or Voyage du Tour du Monde (1719, Paris).[19]

Around the World by Steam, via Pacific Railway, was published in 1871 by the Union Pacific Railroad Company, and an Around the World in A Hundred and Twenty Days by Edmond Planchut. In early 1870, the Erie Railway Company published a statement of routes, times, and distances detailing a trip around the globe of 38,204 km (23,739 mi) in 77 days and 21 hours.[20]

American William Perry Fogg traveled the world, describing his tour in a series of letters to The Cleveland Leader newspaper, entitled, Round the World: Letters from Japan, China, India, and Egypt (1872).[21][22]

In 1872, Thomas Cook organised the first around-the-world tourist trip, leaving on 20 September 1872 and returning seven months later. The journey was described in a series of letters published in 1873 as Letter from the Sea and from Foreign Lands, Descriptive of a tour Round the World. Scholars have pointed out similarities between Verne's account and Cook's letters. However, some argue that Cook's trip happened too late to influence Verne. According to a second-hand 1898 account, Verne refers to a Cook advertisement as a source for the idea of his book. In interviews in 1894 and 1904, Verne says the source was "through reading one day in a Paris cafe" and "due merely to a tourist advertisement seen by chance in the columns of a newspaper." Around the World itself says the origins were a newspaper article. All of these point to Cook's advert as being a probable spark for the idea of the book.[6]

The periodical Le Tour du monde (3 October 1869) contained a short piece titled "Around the World in Eighty Days", which refers to 230 km (140 mi) of the railway not yet completed between Allahabad and Bombay, a central point in Verne's work. But even the Le Tour de monde article was not entirely original; it cites in its bibliography the Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, de la Géographie, de l'Histoire et de l'Archéologie (August 1869), which also contains the title Around the World in Eighty Days in its contents page. The Nouvelles Annales were written by Conrad Malte-Brun (1775–1826) and his son Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun (1816–1889). Scholars[who?] believe that Verne was aware of the Le Tour de monde article, the Nouvelles Annales, or both and that he consulted it or them, noting that the Le Tour du monde even included a trip schedule very similar to Verne's final version.[6]

A possible inspiration was the traveller George Francis Train, who made four trips around the world, including one in 80 days in 1870. Similarities include the hiring of a private train and being imprisoned. Train later claimed, "Verne stole my thunder. I'm Phileas Fogg."[6]

Regarding the idea of gaining a day, Verne said of its origin: "I have a great number of scientific odds and ends in my head. It was thus that, when, one day in a Paris café, I read in the Siècle that a man could travel around the world in 80 days, it immediately struck me that I could profit by a difference of meridian and make my traveller gain or lose a day in his journey. There was a dénouement ready found. The story was not written until long after. I carry ideas about in my head for years – ten, or 15 years, sometimes – before giving them form." In his April 1873 lecture, "The Meridians and the Calendar", Verne responded to a question about where the change of day occurred since the International Date Line only became current in 1880 and the Greenwich prime meridian was not adopted internationally until 1884. Verne cited an 1872 article in Nature, and Edgar Allan Poe's short story "Three Sundays in a Week" (1841), which was also based on going around the world and the difference in a day linked to a marriage at the end. Verne even analysed Poe's story in his Edgar Poe and His Works (1864).[6]

Adaptations and influences

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

The book has been adapted or reimagined many times in different forms.

Literature

- The novel Around the world in 100 days by Gary Blackwood (2010) serves as a sequel to the events in 80 days. The book follows Phileas's son as he travels around the world by car instead of train, hence the longer time limit.[24]

- The novel The Other Log of Phileas Fogg by Philip Jose Farmer (1973) tells the secret history of Phileas Fogg's unprecedented trip, in which two alien races contend for Earth's mastery.

Theatre

- The novel was converted into a play by Verne and Adolphe d'Ennery for production in Paris in 1874. The play was translated into English and brought to the United States by The Kiralfy Brothers.[25]

- Orson Welles produced a musical version with Cole Porter in 1946 called Around the World.

- Another musical version, 80 Days, with songs by Ray Davies of the Kinks and a book by playwright Snoo Wilson, directed by Des McAnuff, ran at the Mandell Weiss Theatre in San Diego from 23 August to 9 October 1988, receiving mixed responses from the critics. Davies's multi-faceted music, McAnuff's directing, and the acting were well received, with the show winning the "Best Musical" award from the San Diego Theatre Critics Circle.[26]

- Mark Brown adapted the book for a five-actor stage production in 2001. It has been performed in New York, Canada, England, South Africa, and Bangladesh.[27]

- Toby Hulse created an adaptation for three actors, which was first produced at The Egg at The Theatre Royal, Bath in 2010.[28] It was revived at the Arcola Theatre in London in 2013 and The Theatre Chipping Norton in 2014.

Radio

- The novel was adapted twice by Orson Welles for his Mercury Theatre broadcasts, 23 October 1938 (60 minutes) and 7 June 1946 (30 minutes).[29]

- Jules Verne – Around the World in Eighty Days, a 4-part drama adaptation in 2010 by Terry James and directed by Janet Whittaker for BBC Radio 7 (now BBC Radio 4 Extra), starred Leslie Phillips as Phileas Fogg, Yves Aubert as Passepartout and Jim Broadbent as Sergeant Fix.[30][31]

Film

- In 1919, a silent film was released. Produced in Germany and starring Conrad Veidt as Phileas Fogg, the film's original German title was Die Reise um die Erde in 80 Tagen. Its original 2 hour and 11 minute running time was later cut by seven minutes. The film was considered lost as of 2002.[32]

- In 1923, a silent serial based on the book was released. Titled Around the World in 18 days, the serial told the story of Fogg's descendant, Phileas Fogg III, and his attempt to recreate his grandfather's journey.

- In 1938, a French/English co-production entitled An Indian Fantasy Story featured the wager at the Reform Club and the rescue of the Indian Princess. However, the production was never completed.[33]

- In 1956, Michael Anderson directed a film adaptation starring David Niven and Cantinflas. The film won five Oscars, including Academy Award for Best Picture

- In 1963, a comedy film The Three Stooges Go Around the World in a Daze starring The Three Stooges in the Passepartout role was released to exploit the popularity of the 1956 film and the Stooges resurgence in popularity that began in 1959.

- In 1910, Serbian writer Branislav Nušić, inspired by the works of Jules Verne, wrote the comedy Travel Around the World (Put oko sveta). This play was later adapted into a film of the same name in 1964, directed by Soja Jovanović, one of the first female directors in the former Yugoslavia. The film was produced by Avala Film.

- In 2000, Warner Bros. released Tweety's High-Flying Adventure in which Tweety flies around the world in 80 days collecting cat paw prints in order to raise money for a children's park. The film was also adapted into a game for the Game Boy Color that same year.

- In 2004, a film was made, loosely based on the book, starring Steve Coogan and Jackie Chan in the roles of Fogg and Passepartout respectively. The adaptation bears less resemblance to the book. The film was nominated for two Razzie Awards.

Television

- Around the World in Eighty Days, a 1972 Australian animated television adaptation.

- The Wonderful World of Puss 'n Boots, a 1976 Japanese cel-animated film.

- Wielka Podróż Bolka i Lolka, a 1978 Polish 15-episode miniseries in the Bolek and Lolek cartoon franchise, where Bolek and Lolek must compete with Fogg's descendant in a bet to repeat his fabled journey.

- Around the World with Willy Fog, a 1984 Spanish animated television adaptation.

- Pierce Brosnan starred as Phileas Fogg in the 1989 mini series with Julia Nickson, Peter Ustinov, and Eric Idle.[34]

- Sir Michael Palin partially attempted to recreate the journey for a documentary series: Around the World in 80 Days with Michael Palin.

- Mickey Mouse Works "MouseTales" segment and House of Mouse episode "Mickey and Minnie's Big Vacation", with Mickey Mouse in the role of Phileas Fogg, Goofy as Jean Passepartout, Scrooge McDuck as Lord Abermarle, and Minnie Mouse as Princess Aouda.

- Around the World in 80 Days, a 2021 international co-produced series starring David Tennant as Phileas Fogg.[35]

Games

- There have been several board games based, often loosely, upon the story.[36][37][38]

- The 2004 mobile video game Around the World in 80 Days is based on the 2004 film.

- The 2005 PC video game 80 Days (2005 video game), developed by Frogwares, is based on the novel.[39]

- The 2014 game of the same name, 80 Days (2014 video game), developed by Inkle, is loosely based on the novel while introducing various science fiction elements.

- The 2020 mobile video game Sherlock: Hidden Match-3 Cases, developed by G5 Entertainment, is partly based on the novel.[40]

Internet

Other

- Worlds of Fun, an amusement park in Kansas City, Missouri, was conceived using the novel as its theme.[43]

- Starting in the second half of the 20th century, and continuing up to the present day (2022), a number of airlines had "Around the World in 80 Days" fares, in which one could take as many flights in one direction as one wanted within the requisite time frame.[44][45]

See also

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.