残割女性生殖器

具爭議性的傳統習俗 来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

残割女性生殖器(Female genital mutilation,FGM),又称为女性生殖器切割(female genital cutting,FGC),或女性割礼(female circumcision)。世界卫生组织将其定义为“包括所有涉及为非医学原因,部分或全部切除女性外生殖器,或对女性生殖器官造成其它伤害的程序”[8][9]。在撒哈拉以南、北非及中东等地区,许多族群将残割女性生殖器视为传统习俗的一部分,目前已知有27个国家境内具有这种风俗[10]。每个地区进行残割女性生殖器的时间不同,有的是在出生后几天,有的则是到青春期才进行。这27个国家中,当中只有一半的国家能够取得统计数据。根据这些资料显示,大多数的女孩在5岁之前就会进行残割女性生殖器[3]:50。

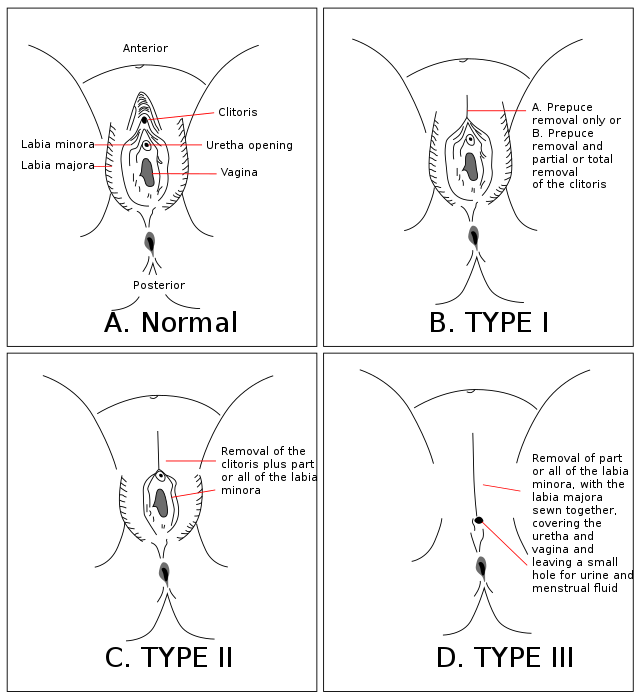

不同民族之间的执行过程不尽相同,有些切除部分阴蒂和阴蒂包皮,也有的切除整个阴蒂和小阴唇;甚至将大小阴唇全部切除,使阴道愈合,俗称锁阴手术,世界卫生组织(WHO)则称为“第三型残割女性生殖器”。被锁阴后的女性下体仅剩下一个小孔,让尿液和经血排除,直到要进行性交及生育时才再次将阴道口打开。残割女性生殖器所造成的影响因操作程序不同而有所差异,包含反复感染、囊肿、不孕症、生产时并发症及致命性出血[11]。目前残割女性生殖器并没有任何已知的医疗助益[12]。

残割女性生殖器是女性的性控制,具有性别不平等的意味。执行残割女性生殖器的地区将此举视作纯洁、端庄与美丽的象征,且认为残割女性生殖器可以帮助女性保守对丈夫的忠贞[13]。手术通常由家族中的女性成员操作,因为她们认为没有进行残割女性生殖器会使她们的女儿或孙女遭受社会排斥[a]。截至2016年,逾2亿名女性已接受过FGM,并分布于30个国家。联合国人口基金预估,截至2010年,20%的已残割人口曾经经历过锁阴手术。此类习俗主要分布于北非,特别是吉布提、厄立特里亚、索马里和苏丹[15][16]。

在上述具有残割女性生殖器习俗的国家,大多明令立法禁止这类风俗,但成效不彰。自从1970年代起,各国纷纷说服人们废止它。2012年,联合国大会认定残割女性生殖器违反人权[17]。但并非无人反对干预此习俗,特别是人类学家。埃里克·西尔弗曼表示,残割女性生殖器已经成为人类学的一项中心道德议题,因其涉及文化相对论、人权的普世性和宽容性等难题[18]:420, 427。

词源

1980年以前,切除女性生殖器的习俗通常被称为“female circumcision”(女性割礼),暗示其与男性割礼的相似性[19]。1929年,在苏格兰长老会传教士马里昂·史蒂文森领导之下,肯尼亚宣教协会开始将此习俗视为对女性的一种性伤害[20]。到了1970年代,将FGM视为性伤害的人数增加[21]。人类学家罗斯·欧德菲尔德·海耶斯(Rose Oldfield Hayes)在1975年的一篇论文标题中首次使用了“female genital mutilation”(残割女性生殖器)这个名词;1979年,奥地利裔美籍学者弗兰·霍斯肯在她的重要论文《霍斯肯报告:女性生殖器及性器官残割》(The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females)中,确立了“female genital mutilation”这个名词。[b]

其后,泛非洲影响妇女及儿童的传统医疗实务协会于1990年始用“female genital mutilation”这个词汇[23];而在1997年4月,世界卫生组织、联合国儿童基金会(UNICEF),和联合国人口基金(UNFPA)同样宣布采用“female genital mutilation”一词为描述女性割礼的术语,其他医疗人士同时也使用包括“female genital cutting”(女性生殖器切割)之同义词汇称之[24]。

在具有女性割礼盛行的地方,则对于此习俗有许多称呼[25],通常与纯洁的意象有关。比如说,阿拉伯语男性割礼(tahur)和女性割礼(tahara)中,带有“t-h-r”的字根,而这类字根则通常带有纯洁的意思[26]。在马里的班巴拉语中,男性或女性割礼皆称为“bolokoli”,意指“洗净双手”。东尼日利亚的伊博语则将其称为“isa aru”或“iwu aru”,则为“沐浴”之意[27]。

圣行割礼通常又称为阴蒂切除术,但也用于更极端的形式;圣行阿拉伯语中意为“行为”、“道路”,也意指传统的穆罕默德,但过程其实和伊斯兰教无关[28]。锁阴手术一词的拉丁文“infibulation”源自于扣环(fibula)。据说古罗马时期,为避免奴隶性交,会使用扣环紧扣于他们的包皮或阴唇[29],苏丹和埃及苏丹人将女性锁阴手术称为“法老的割礼”[29],但古埃及仅有男性有割礼,女性并无此习俗[30]。索马里则称之为“qodob”意指“缝合”[31]。

割礼进行方式

女性割礼通常由女生家中的传统割礼师执行。割礼师通常是较老的女性,但在有些社区,男性理发师兼任健康工作者,也会负责执行这项手术[32][c][33]。在埃及、苏丹和肯尼亚,通常会有专业的医疗人士陪同。根据一项2008年的调查,在埃及77%的女性割礼会由专业医疗人士陪同,通常是内科医生[34]。

当由传统割礼师执行仪式时,很有可能是使用没有消毒的切割器具,包括刀子、激光、剪刀、玻璃、磨利的石头和指甲[35]。一位乌干达的护士曾在2007年的《柳叶刀》(The Lancet)说,一位割礼师可能会同时用同一把刀,为30位女性执行这个仪式[36]。手术过程可能会进行全身麻醉或是局部麻醉,有时甚至不进行任何麻醉,取决于专业医疗人士的判断和参与程度。曾有1995年的报导指出,在埃及,60%的情况会进行局部麻醉,13%全身麻醉,而25%完全不进行任何麻醉[37]。

残割的种类

1997年4月,世界卫生组织(WHO)、联合国儿童基金会(UNICEF)和联合国人口基金(UNFPA)发表了一份联合声明,明确定义了“女性残割”的内容:“无论是因文化还是其他非治疗性的原因,凡是涉及部分切除、全部切除女性外生殖器,或是其他伤害女性生殖器官的步骤流程,皆被归类于‘女性残割’”[38]。

而“女性残割”的步骤根据不同的族群以及不同的医疗从事人员也会有所不同。 1998年在尼日尔的调查显示,当女性受访者被问及其自身所遭遇的“女性残割”过程,其回答的内容超过50种不同的类型[25]。然而,在受访者回答其所遭遇的“女性残割”类型,甚至是否曾经遭遇这样简单的问题,由于语言的隔阂,使得调查研究的数据可靠性产生质疑。有些研究甚至认为这些受访者的受访内容其可信度是不可靠的。而在2003年加纳的研究指出,在1995年约有4%的受访女性不曾遭受“女性残割”,然而在2000年,这一群女性中其中有 11 % 的受访者,也遭受了“女性残割”。在坦桑尼亚的研究中,有 66 %的受访女性是曾遭受“女性残割”,但在实际的体检结果,却证实了其中有73%的女性曾遭受“女性残割”[39]。 而给予受访者的标准问卷问题内容如下:

- 切割,但无肉体组织被移除 (意即穿刺,或象征性的割礼);

- 切割,而有一部分的组织被移除

- 完全缝合密闭

- 其他不确定或是未知的类型[d]

大多数的步骤流程皆被归类于“切割,有部分的组织被移除”,其中还涉及完全的移除或是部分的移除女性阴蒂头[40]。

世界卫生组织目前根据组织被移除的多寡,将女性割礼很详尽地归类为类型I - III,而类型 III 指的是“完全缝合密闭”。另外,类型 IV则是对于象征性的割礼与其他杂项步骤流程进行描述[41]。

- 类型 I 又可细分为Ia与Ib两细项:

- Ib:即阴蒂切除术,此类型较1为普遍。即部分或是完全的切除阴蒂头与阴蒂包皮。Susan与Nahid Toubia曾在论述中提及:“阴蒂头被以拇指和食指捏著拉出来,并以尖锐的物品切下。”[43]

- 类型二

世卫组织定义的女性器切除类型二指部分或全部切除小阴唇,有时也切除大阴唇或阴蒂头。

类型二又可分为三细项:

- IIa:仅切除小阴唇。

- IIb:切除部分或全部切除阴蒂头和小阴唇。

- IIc:切除部分或全部切除阴蒂头、小阴唇和大阴唇。

第三型(锁阴手术或残暴割礼),属于缝合类别,是将外阴部去除并将两侧伤口互相缝合。小(或和大阴唇)会被切除,阴蒂则不一定。第三a型是将小阴唇去除缝合,而第三b则处理外阴唇[f]。此作法常见于位于非洲东北部的吉布提、厄立垂亚、埃塞俄比亚、索马里和苏丹(不包含南苏丹)。数据估计之变化:根据一篇2008年的研究,超过800万非洲女性有此经历[g]。根据联合国人口基金会于2010年的调查显示,20%接受残割女性生殖器的女性被施行缝阴手术[15]。

专业助产士卡姆福特·莫莫如此描述锁阴手术:“年长女性和亲友们会将女孩调整至切石卧位。之后她们会快速地深切两侧的阴蒂根部,直至小系带。之后再使用剃刀直接切除大小阴唇。”[46]在索马里,女孩的阴唇被切下之后,会被拿给年长女性,以确认手术是否完全[47]。

确认之后,执刀者会在伤口中插入物品(如树枝),为女性的阴部留下一个 2–3 mm 的开口,供经血和尿液排出[h][49],并以手术用缝线(也可能是龙舌兰或金合欢属植物的刺)缝合外阴。有些手术者会在伤口敷上药膏,药膏可能是以生蛋、药草或是砂糖等调配而成[50]。为了帮助伤口愈合,女孩的双脚会被捆绑起来(通常是从髋部绑到踝部)。捆绑的时间不一定,通常一周后会放松,两周后会完全解开,有些则可能长达六周[51]。

专业助产士卡姆福特·莫莫 亦曾如此描述:

(阴道开口处)是由鼓膜般的皮肤延伸覆盖外阴处所余之小孔。在执行切除的情况下,女孩多半会被牢牢固定住,但亦可能因剧烈挣扎,导致切口不受控制或杂乱无章;甚至可能因挣扎时用力过度而骨折或脱臼。[46]

若女孩的家人认为锁阴手术后留下的开口太大,会再进行锁阴手术[52]。阴部的洞会在结婚后为了性交而开启,第一次可能是助产士用小刀先割开,也有可能是她的先生直接用阴茎顶破。在包括索马里兰在内的一些国家,新郎及新娘的女性亲友会观看新娘阴部的开口,以确认她婚前未进行过性行为[53]。心理学家洪尼莱特富特 - 克莱因(Hanny Lightfoot-Klein)在1980年代采访过上百对苏丹的女性及男性,访问有关接受锁阴手术后的性行为:

若新娘已进行过锁阴手术,新郎想直接用阴茎顶破锁阴手术处,插入阴道进行性行为,以一般夫妻行房的频率,约需要三至四天至数个月不等。有些男性因为锁阴手术,完全无法进行阴道插入式性行为(在我的研究中,约占15%),一般会由助产士进行手术切开,不过因为这反映男性的性能力较弱,因此会在非常秘密的情形下进行。有些无法进行插入式性行为的男性,即使在锁阴手术的开口未打开的情形下,仍设法要让妻子怀孕,若妻子怀孕了,其阴部的开口会切开以便分娩。有些(也许是所有)有这类情形的男性会用小刀协助打开妻子阴部的开口,过程中会疼痛,因为其阴部是渐渐撕裂越来越多,直到开口处可以让阴茎插入为止。[54]

女性在分娩时阴部被再次打开,分娩后再将之缝合,此过程称为去缝阴手术和再缝阴手术。再缝阴手术包含再次剪开阴道来重建回第一次缝阴手术保留的那针孔大小的阴道口。此手术大约在婚前、分娩后、离婚和丧偶时执行[i][56]。

世界卫生组织定义第四型为“所有其他对女性外生殖器有害的非医疗性行为”,包括刺入、刺穿、切割、刮除和烧灼。[2]它包括切割阴核(象征性的割礼)、烧灼或使阴部有疤痕,和植入物体到阴道使之更紧。[57]阴唇牵拉也归类为第四类。[58]常见于非洲南部和东部,此法是为了增强男性的性快感,而添加一种封闭空间感于女性。从八岁开始,就鼓励女孩使用棍棒和按摩伸展其小阴唇。乌干达女孩被教育若无伸展阴唇则很难分娩。[j][60]

世界卫生组织在1995年针对残割女性生殖器的定义有包括在尼日尔及尼日利亚进行的吉西里切割[k](gishiri cutting)或安古利亚切割(angurya cutting)。因为有关其发生率及程序资讯的不足,世界卫生组织2008年的定义中已不包括这些方式[58]。吉西里切割是为了处理不孕及难产等几种问题,用刀片切割阴道前壁或后壁。在尼日利亚医生马里奥·乌斯曼·曼达拉(Mairo Usman Mandara)的研究中,进行过吉西里切割的女性,超过30%会有膀胱阴道瘘的问题。安古利亚切割是将处女膜切除,会在出生后第七天进行[61]。

并发症

残割女性生殖器对女性一生的身体及情绪健康都是有害的[63][64],对于健康没有任何已知的帮助[65] 。其短期及后续的并发症和进行的残割女性生殖器种类,施行者是否有手术经验,是否有用抗生素、用未消毒的手术器材或是医疗用的单次使用器材有关。若是进行锁阴手术,后遗症的严重程度有许多影响因子,包含手术后所留下的孔穴大小、缝合是用手术用缝线还是植物的刺,以及程序是否进行不只一次(例如因为留下的孔穴太大而重新缝合,或是因为留下的孔穴太小而再开启一个孔穴)等[45]。

手术后的常见并发症包括肿胀、出血过多、疼痛、尿滞留,或伤口感染。2015年的一份采集了56篇研究的回顾文章中提到,逾十分之一的女性在残割女性生殖器后发生了上述的并发症,其中的残割女性生殖器甚至包括象征性的阴蒂切口(第四型),不过第三型的风险仍是最高的,报告也中认为此结果可能有低估[66]。其他短期症状包括致命的大量出血、贫血、泌尿道感染、败血症、破伤风、坏疽、坏死性筋膜炎(细菌将组织"吃掉")及子宫内膜炎[45][64][67]。因为这类的并发症可能没有识别或是汇报,因此不确定有多少名女性因为这些并发症而死亡[68][69]。手术者可能会用同一套器具为不同的人进行手术,这可能也会造成乙型肝炎、丙型肝炎及HIV的扩散,不过还没有流行病学的研究可以证实这一点[69]。

后续的并发症因女阴割残的类型不同而异[45]。并发症包含导致难产的疤痕和蟹状瘤、受感染的表层状囊包,也会影响阴蒂相关的神经增生[70][71]。受到阴户缝合的女生可能会在阴户留有2-3mm的孔洞,这个洞会造成解尿迟缓、滴尿、小便时疼痛,以及频尿等症状。尿液可能会在伤痕下聚积,造成皮肤底下长年潮湿,有可能会导致感染以及结石。有性行为或自然产的妇女在阴户上会有较大的孔穴,但还是会因为伤痕组织而造成尿道开口受阻难产。可能会出现膀胱阴道瘘或直肠阴道瘘(也就是阴道和尿道之间或是直肠和阴道之间有异常通道)[45][72]。这些损害以及其他对尿道及膀胱的伤害可能会造成感染、尿失禁、性交疼痛及不孕[70]。

由于月经期产生的经血淤塞、滞留在阴道和子宫而造成的痛经也很常见。如果阴道完全堵塞,会造成阴道积血或子宫积血[45]。由于经血淤积造成的腹部肿胀和不来月经,使女孩看起来像是怀孕。雅斯玛·艾尔·达理尔(Asma EI Dareer)医生在1979年报告,一名有上述症状的年轻苏丹女孩被其家人所杀[73]。

残割女性生殖器会提高女性在怀孕及生产时的风险,残割女性生殖器的普及率越高,这部分越明显[45]。接受锁阴手术的妇女会为了使生产容易一些,会在怀孕期间吃的较少,以减小胎儿的体积[75]。若女性有膀胱阴道瘘或是直肠阴道瘘,很难在产前检查中采集到纯淬的尿液检体,因此更不容易诊断出妊娠毒血症[70]。在分娩时无法进行宫颈评估,可能会造成滞产或难产。锁阴手术的妇女更常出现三度撕裂伤,肛门括约肌损伤及紧急的剖宫产[45][76]。

残割女性生殖器也会提高新生儿死亡的比例。世界卫生组织在2006年针对非洲部分地区统计,在统计每一千名出生的新生儿中,就有10至20个新生儿死亡是因为残割女性生殖器造成。此 统计资料是由布基纳法索、加纳、肯尼亚、尼日利亚、塞内加尔和苏丹的28个产科中心,对28393分娩妇女进行的研究。上述地区的研究发现,各种的女阴残 割都会提高新生儿死亡的风险,其中第一型残割女性生殖器占15%,第二型及第三型残割女性生殖器分别占32% 及55%,其原因还不清楚,但可能和性器官及泌尿道的感染以及瘢痕组织的存在所造成。研究者认为残割女性生殖器和母亲会阴的受损及产后出血有关,也可能会让婴儿需要接受心肺复苏,甚至死产,其原因可能和分娩中,胎儿娩出的第二阶段时间过长有关[77]。

关于残割女性生殖器造成的心理影响,根据一篇2015年发表的系统综述表明,现行几乎没有可靠的信息。一些小型的调查发现,受过残割女性生殖器的女性遭受焦虑、抑郁和创伤后心理压力紧张症候群的困扰[69]。当受过残割女性生殖器的女性离开进行割礼的文化社群,发现残割女性生殖器并不是一种正常现象之后,她们会感到耻辱和被背叛;但如果这些受过残割女性生殖器的女性依然留在进行割礼的文化社群中,她们会为自己受过割礼而感到骄傲,因为对于她们来说,残割女性生殖器意味着美丽、尊重传统、和贞洁[45]。

几乎没有研究探讨残割女性生殖器对性功能造成的影响[69]。一份在2013年发表的元分析报告,在分析了15个调查、总共涵盖了来自7个国家的12,671名受过残割女性生殖器的女性后发现,受过割礼的女性感到毫无性欲的可能性是未受过割礼女性的两倍,而且报告性交疼痛的几率高52%。一共有1/3的调查者报告性欲减退[78]。

分布

残割女性生殖器的盛行区域位于非洲,东迄索马里,西至塞内加尔,南至坦桑尼亚、北至埃及。政治科学家Gerry Mackie称此区域为“令人感兴趣的连续区”(intriguingly contiguous)[79]。截至2014年年[update],29个盛行国家中,已有1.3亿名女性已经接受过残割女性生殖器。预估到2050年,此数字会随人口增加而上升至2亿[l]。

2013年时埃及、埃塞俄比亚和尼日利亚有最多的女性与女孩遭遇残割女性生殖器,估计分别是2720万人、2380万人以及1990万人[81](埃及于2007将残割女性生殖器视为违法行为、埃塞俄比亚在2004年、尼日利亚则是在2015年)[82][83][84]。2014年,残割女性生殖器在南撒哈拉地区成年女性盛行率为39%,对于14岁以下的女孩,盛行率为17%。在西非与南非这个比例分别是44%与14%,西非与中非为31%与17%[5]。

上述的资料是由人口与健康调查组织(DHS)的家户调查而来,是由Macro International所提供,资金来源主要是来自美国国际开发署及多指标集调查组织提供,由联合国儿童基金会提供的技术及财务支援[85]。调查是在非洲、亚洲及拉丁美洲等地进行,自1984年及1995年进行,约每五年进行一次[86][87]。

第一份有关残割女性生殖器的调查是1989年至1990年由人口与健康调查组织(DHS)在北苏丹进行的调查,第一份估计残割女性生殖器盛行率的出版物是1997年由Macro International的Dara Carr制作,根据七个国家的DHS资料整理而得[88]。联合国儿童基金会2013年根据70份调查所得的报告,指出残割女性生殖器集中在非洲的27个国家、也门及伊拉克的库尔德族[89],在这些国家中有1.33亿位女性进行了残割女性生殖器[90]。

在上述29个国家以外,在印度、阿联酋、以色列的贝都因人有残割女性生殖器的记录,在哥伦比亚、刚果、阿曼、秘鲁及斯里兰卡也有出现过,但不常见[91]。在约旦、沙特阿拉伯、印尼及马来西亚以及澳大利亚、新西兰、欧洲、斯堪的纳维亚、美国及加拿大的移民群体也有这类的情形[m][93]。

在有残割女性生殖器的国家中,多半不是所有女性接受残割女性生殖器,而是会随着种族而不同[95]。例如在伊拉克,残割女性生殖器主要是出现在库尔德人中,分布在阿尔贝拉(15至49岁的当地库尔德女性有58%接受残割女性生殖器)、苏莱曼尼亚(54%)及基尔库克(约20%),全国接受残割女性生殖器女性比例有8%[96]。

有时残割女性生殖器是一个种族的标志,但有时也会随所在家而不同。埃塞俄比亚和肯尼亚的东北部邻近索马里。在这三个国家索马里人残割女性生殖器的比例相近[97]。不过根据2001年的问卷,所有几内亚的富拉尼人女性都有进行残割女性生殖器[98],在查德的富拉尼人只有12%进行过,而在尼日利亚,富拉尼人是唯一不进行残割女性生殖器的主要族群[99]。

中东的库尔德地区也广泛存在残割女性生殖器的行为,2011年6月,伊拉克库尔德三省将女性割礼和家庭暴力列入刑事犯罪,这是个具有里程碑意义的法律,但始终无法获得有效实施。在伊拉克北部库尔德三省,享有很大的自主权,库尔德当地人平均寿命特别是女性也比伊拉克其他省份要好。但在当地有切割女性生殖器官的传统。据德国非政府组织2010年的对当地1700名妇女的调查中发现在埃尔比勒和苏莱曼尼亚两个省份中72.7%的女性都被切割了生殖器,某些地区几乎100%。此外许多库尔德女性由于畏惧强奸和荣誉谋杀而自愿将下体缝合,部分人甚至选择切除输卵管并将下体完全缝合,终身不嫁。[100]

研究发现残割女性生殖器较常出现在乡村地区,最富裕家庭的女性进行残割女性生殖器的比例较少。大部分国家中,若女性接受小学或小学以上的教育,其女儿接受残割女性生殖器的比例会较少,但苏丹及索马里例外,索马里女性若接受中学或中学以上的教育,她的女儿接受 残割女性生殖器的比例反而会增加。在苏丹境内,女性只要有接受教育,女儿接受残割女性生殖器的比例就会上升[101]。

在问卷中,以下是有关残割女性生殖器种类的问题[102]

- 女阴部位是否只穿孔或切割,但没有切除性器的任一部位?

- 女阴是否有割除任何部位?

- 女阴部位有缝合(锁阴手术)吗?

大部分有受过手术的女性会回答:“切除部分部位”,属于WHO分类的第1类及第2类[40]。第1类及第2类在埃及都有人进行[n]Mackie在2003年提出第2型比较常见[104],而2011年的一份研究指出第1型比较常见[105]。在尼日利亚南部较常看到第1型,北部则是更严格的残割女性生殖器[106]。

第3型(锁阴手术)集中在非洲东北部、特别是吉布提、厄立特里亚、索马里及苏丹[107]。在2002年至2006年的问卷中,吉布提进行过残割女性生殖器的女性中,有30%是进行锁阴手术,在厄立特里亚和索马里分别是38%及63%[108]。在尼日尔及塞内加尔的女性进行锁阴手术的比例也比较高[109]。2013年在尼日利亚14岁以下的女童中,估计有3%有进行锁阴手术[110]。在厄立特里亚,这类的手术和其种族有关,例如2002年有一份统计指出,所有Hedareb族的少女都进行了锁阴手术,而提格里-提格利尼亚族只有2%,她们大部分是进行“只切割,没有切除性器任一部位”的残割女性生殖器[25]。

残割女性生殖器不一定是从女孩变为女人之间的成年礼,不过常常在女儿年龄较小时进行[112]。女性一般是在刚过15岁之后进行[111]。在一些国家有相关的统计数据,其中有一半的国家其女性是在约五岁时进行残割女性生殖器[111]。在尼日利亚、马里、加纳及毛里塔尼亚有进行残割女性生殖器的女性中,有80%是在五岁前进行残割女性生殖器[113]。1997年也门的人口及健康统计指出76%的女婴是在出生后二周就进行残割女性生殖器[114]。

在索马里、埃及、查德及中非共和国的情形则所有不同,进行残割女性生殖器的有80%是在五岁至十四岁之间进行[113]。残割女性生殖器的种类和种族有关,平均年龄也是,在肯尼亚,Kisi族平均在十岁进行残割女性生殖器,坎巴族则是在十六岁[115]。

根据UNICEF 2013年的调查,在29个国家中比较15至19岁和45至49岁残割女性生殖器的比例,有一半的国家呈现下降的趋势[116]。残割女性生殖器比例很高的国家,其变化不大,但原本残割女性生殖器比例就较低的国家,其比例正在下降,或者采用较轻微的方式[117]。根据UNICEF 2014年的资料,女孩接受残割女性生殖器的比例较30年前低了1/3[118]。

回应有关残割女性生殖器问卷的女性,是表示她们之前是否有进行过残割女性生殖器,因此15岁到49岁的发生率不表示目前的趋势[120]。UNICEF以15岁到49岁为基准,因为14岁以下的女孩都有后续会进行残割女性生殖器的风险[o]。另一个造成发生率判断上的困扰是在反对残割女性生殖器的国家,母亲比较不会说自己的女儿其实已进行了残割女性生殖器[121]。

在2010年时DHS及MICS的问卷开始问妇女她们的女儿是否有进行残割女性生殖器[122],问卷指出0–14岁残割女性生殖器发生率最低的是在贝宁的0.3%(15至49岁比率为7%),最高的是马里74%(15至49岁比率为89%)[5]。

埃及在2008年至2010年之间有进行一项研究(埃及在2007年法律禁止残割女性生殖器,2008年视为犯罪行为),针对索哈杰及基纳大学医院中的4158名女性以及5岁至25岁的女孩进行有关残割女性生殖器的问卷。研究者指出 在埃及以第1型的残割女性生殖器最为常见。在2000至2009年之间,受访者有3711个已进行了残割女性生殖器,比率达89.2%[p]。2000年进行残割女性生殖器的比率有9.6%,在2006年开始下降,2009年下降到7.7%。在2007年后大部分的残割女性生殖器是由一般的外科医生进行,研究者推测这是因为残割女性生殖器视为犯罪行为,妇产科医生不愿意执行,因此改由一般外科医生进行[105]。

原因

索马里的女诗人Dahabo Musa在其1988的诗中将锁阴手术描述为“三次女性的伤痛”:锁阴手术本身、在新婚的初夜将阴部打开、在分娩后再将阴部缝合[123]。虽然有明显的痛苦,但在有残割女性生殖器习俗的地区,都是女性在组织管理包括锁阴手术在内的各种的残割女性生殖器。人类学家 Rose Oldfield Hayes在1975年提到住在城市的受教育男性不希望其女儿接受锁阴手术(比较倾向接受阴蒂切除术),但可能某一天他的母亲安排亲戚来访,也就帮孙女作了锁阴手术[124]。Gerry Mackie比较残割女性生殖器及缠足。缠足和残割女性生殖器有些类似,都是因为荣誉、女性贞节、认为对婚姻有益,也都是受到其他女性长辈的支持[q]。

图 1996年普立兹普立兹特写摄影奖

— Stephanie Walsh, Newhouse News Service[126]实现残割女性生殖器的人认为残割女性生殖器主要是表示性别的差异,依此观点,残割女性生殖器是对女性的去男性化,而男性的割礼是对男性的去女性化[127]。Fuambai Ahmadu是塞拉利昂科诺族的人类学家,在进入桑德社群时接受了阴蒂切除术,作为成人的象征。她认为强调阴蒂在女性性机能中重要性的想法是男性中心的假设,非洲的女性符号是子宫的受孕[128],锁阴手术强调封闭及受孕的概念。加拿大人类学家Janice Boddy提到:“阴蒂切除完成了孩童性器官的社会定义,去除了外在轮廓上的雌雄同体。因此女性的身体是被包覆的、封闭的,有生育能力的血液封闭在其中,而男性的身体是不隐藏的、开放的,暴露的。”[129]

在习惯进行锁阴手术的族群中,一般会希望女性的生殖器是光滑、干燥、无气味的,不论男性或女性都会排斥自然正常的外阴[130]。男性似乎会享受用阴茎将锁阴部位顶开的成果[131]。由于进行过锁阴手术的外阴较光滑,这些族群也认为锁阴手术有助于清洁卫生[132]。女性会为了减少阴道润滑而在阴道中塞入树叶、树皮、牙膏等物品。世界卫生组织将这类的行为归类在第4型残割女性生殖器中,因为这些在性交中增加的摩擦会造成破皮,也会提高感染的风险[133]。

在问卷中女性支持残割女性生殖器的常见理由包括社会认同、宗教、清洁卫生、保持贞节、适于结婚及增加男性的性快感[134]。在一份1983年发表,针对北苏丹的研究中指出,3210名女性中只有558人(17.4%)反对残割女性生殖器,赞成的人赞成阴唇切除及锁阴手术过于阴蒂切除术[135]。不过女性的态度也在慢慢改变。2000年时苏丹有42%知道残割女性生殖器的女性认为此作法需继续实施[136]。在2006年时,在马里、几内亚、塞拉利昂、索马里、冈比亚及埃及有超过50%的女性认为应该继续残割女性生殖器,而在非洲其他地区、伊拉克及也门的大部分女性认为不应该再进行残割女性生殖器,不过在一些国家中,赞成和反对的比例其实差距不大[137]。

针对那些愿意为其女儿进行残割女性生殖器的女性,联合国儿童基金会认为这是:“自我执行的社会习俗”,这些家庭认为需要遵守,以避免没进行残割女性生殖器的女儿遭到社会的排斥[138]。

美国人类学家Ellen Gruenbaum在1970年代研究指出,阿拉伯人中已接受女性残割的女孩会嘲笑哪些没有接受女性残割的哲尔马女孩:“嘿!脏鬼!”(Ya, Ghalfa!),哲尔马女孩会反讽他们“mutmura”(mutmura是一种谷仓,常需要打开及关闭,就像接受锁阴手术的女性一样)。不过她们仍会感受到压力,回去会问母亲说:“怎么回事!我们没有像阿拉伯人一样的小刀(可以进行锁阴手术)吗?”[139]

由于相关的医学资讯的不足,也因为施行残割女性生殖器者会对残割女性生殖器的后果加以淡化,因此,女性不会将其身体健康的情形和残割女性生殖器联想到一起。拉拉·白尔德(Lala Baldé)是塞内加尔梅迪纳·谢里夫村(Medina Cherif)的女性组织领袖,她在1998年告诉Mackie说,当女孩们生病甚至死亡时,会归因于邪灵的影响。当其他女性知道残割女性生殖器和健康恶化之间的因果关系时,她们崩溃痛哭。他认为在提供这些资讯前后的调查,可以看出对残割女性生殖器的支持程度有非常明显的变化[140]。

1991年由Molly Melching成立的美国非营利组织Tosta在许多国家提出了社区赋权方案,着重在识字、卫生相关教育及地区的民主,让女性可以做自己的决定[141]。1997年Malicounda Bambara配合Tostan方案,成为第一个废止残割女性生殖器的村庄,在2014年在八个国家已有超过七千个社群放弃残割女性生殖器和童婚[142]。有一个联合国人口基金会和联合国儿童基金会的联合计划2014年为止已在非洲十五个国家进行,也是依相同的方式进行[138]。

问卷发现非洲有许多人认为残割女性生殖器是宗教上的要求,特别是在马里,茅利塔利亚,几内亚及埃及等国家,有此想法的人特别的多[144]。格林鲍姆(Gruenbaum)提到当地的人不太会区分此实务是出于宗教、习俗还是贞操,因此不太容易说明这数据进一步的意义[145]在一个联合国人口基金及联合国儿童基金会合作的计划案中,在2008年到2013年间,有20941位宗教领袖及传统领袖公开说明残割女性生殖器和宗教无关,宗教领袖发出了2898篇宗教敕令,反对残割女性生殖器[146]。

虽然残割女性生殖器最早出现在东北非的时间是在伊斯兰教之前,不过因为伊斯兰教强调女性的贞操及隔离,因此此一实务开始认为和伊斯兰教有关[r]。在可兰经中没有提到残割女性生殖器,在数篇圣训(一般认为是记录穆罕默德的言行录)中赞赏这种行为,认为是高贵的,但不是必须的,其中也有建议使用较温和的方式,对妇女比较仁慈[s][149]。2007年在开罗举行的艾资哈尔大学伊斯兰研究最高委员会中认定:“残割女性生殖器在核心伊斯兰教法及其他部分规定中都没有依据。”[150][t] 也有泛灵论的族群进行残割女性生殖器,特别是在几内亚及马里。也有基督徒进行残割女性生殖器的情形[152],例如在尼日尔,约有55%的基督徒妇女及女孩进行了残割女性生殖器,而穆斯林族群中只有2%[153]。圣经上只提到男性的割礼,没提到残割女性生殖器,而到非洲的宣教士是最早反对残割女性生殖器的一群人之一[154]。非洲的犹太教族群中只有埃塞俄比亚的贝塔以色列人有进行女性器切除。犹太教要求男性实行割礼,反对残割女性生殖器[155]。

历史

咒语1117

“如果一个人想要知道如何生活,必须使用来自未受残割女性生殖器女子['m't]的b3d(埃及象形文字代号,含义未知)和未受割礼的秃头男子的皮屑 [šnft]摩擦全身,并每日覆诵之(一段咒语)。”

——来自埃及棺木上的一段铭文,公元前1991-1786[156]现在不清楚残割女性生殖器的起源[157]。Gerry Mackie根据残割女性生殖器的分布,猜测这是起源自麦罗埃文明和帝国的一夫多妻制,这是在伊斯兰教兴起之前,为了增加父亲的信任[158]。

根据历史学家Mary Knight的研究,古埃及棺材文本中的咒语1117用圣书体提到一名未受残割女性生殖器的女子('m't):

上述的咒语出现在Sit-hedjhotep的石棺中,石棺现在在埃及博物馆,大约是埃及中王国时期的产物(Paul F. O'Rourke认为'm't 可能反而是指一个受残割女性生殖器的女子)[159]

在大英博物馆中有一份公元前163年的希腊文莎草纸,上面提到一个应该已经被残割女性生殖器(但其实没有进行)的埃及女孩Tathemis:

在这件事之后,Nephoris(Tathemis的妈妈)骗我,而且开始焦虑,因为依照埃及人的习俗,那时应该是Tathemis要接受割礼的时候。她要我给她她1,300银币,好帮Nephoris买衣服并且准备她的嫁妆。若她在第18年(公元前163年)的Mecheir月时,二项没有都达成,或是Tathemis没有进行割礼,她要立刻赔给我2,400银币[160]。

澳大利亚病理学家 Grafton Elliot Smith 在二十世纪初检查了上百具木乃伊,指出无法从木乃伊找到进行残割女性生殖器的证据。由其阴部来看,像是第三型的残割女性生殖器,因为在制作木乃伊的 过程中,大阴唇的皮肤被拉到肛门处以覆盖阴裂,可能是为了避免性暴力。因为软组织可能被尸体防腐者除去或是已被腐化分解,因此也无法确定是否有进 行过第一型或第二型的残割女性生殖器[161]。

希腊地理学家斯特拉波(公元前64年至公元23年)在公元前25年造访埃及后,写下了有关残割女性生殖器的描述(如右)[u][v]。哲学家斐洛(公元前20年至公元50年)也写道:“埃及人依照其国家的习俗,会在十四岁的少年及少女举行割礼,那时少年已开始有精子,少女也开始有月经。”[165]有一份认为是希腊医师盖伦写的文章中也有提到:“当年轻女性的阴蒂大幅度伸出时,埃及人会认为应该将其切除。”[166]

另一位希腊医生阿弥陀的埃提乌斯(第 5世纪中至第6 世纪中)在其"Sixteen Books on Medicine"中的第16本中,引用了医生Philomenes的话。当阴蒂长的太大,或是当和衣服磨擦时会引发性冲动时,就会进行残割女性生殖器。埃提乌斯说:“这种情形下,埃及人似乎认为在阴蒂大幅变大之前切除会比较妥当,尤其是少女快要嫁人的时候。”

手术是以这样的方式进行:少女坐在椅子上,一个充满肌肉的少年站在她后面,手臂在少女的大腿下面,让少女的腿分开,并且稳住身体及腿。医生站在少女前面,用左手的泛口钳夹住少女的阴蒂,并且往外拉,右手从钳夹住的点割下阴蒂。

阴蒂不会完全切除,会保留部分的组织,长度大约会和鼻孔相当。手术只是为了切除过多的组织。因为阴蒂是类似皮肤的组织,若割除太多,怕会出现尿瘘的情形[167]

接下来会用海绵、乳香粉、酒或冰水清理外阴道,然后用浸满醋的亚麻绷带包扎至第七天,接着使用炉甘石洗剂、玫瑰花瓣、枣核或是“烤过黏土制成的阴部涂抹粉末”[168]。

锁阴手术的起源不明,但后来演变成和奴隶有关。Mackie曾引述葡萄牙宣教士 João dos Santos在1609年提到摩加迪沙群岛上人们的文字:“他们的习俗㑹将女性(的阴部)缝合,特别是年轻的女奴,使她们无法生育,也让女奴 比较好卖,一方面是贞节,也有助于主人对她们的信任。”英国的探险家威廉·乔治·布朗在1799年也写到埃及人会进行残割女性生殖器,而且会为女奴进行锁阴手术以避免怀孕[169]。Mackie认为是:“一项和女奴有关的手术变成了荣誉的象征。”[170]

19世纪欧洲及美国的妇产科医生用切除阴蒂的方式来治疗精神错乱及女性的自慰[172]。英国医生罗伯特·托马斯在1813年建议用切除阴蒂来治疗色情狂[173]。第一个有记录的西方切除阴蒂是记载在1825年的《柳叶刀》杂志上,是1822年在柏林由卡尔·费迪南德·冯·格雷夫进行,是对一位十五岁,自慰过度的女性所施行的手术[174]。

艾萨克·贝克·布朗是英国的妇产科医生,伦敦医学会的主席,也是1845年伦敦圣玛丽医院的共同创办人,他相信自慰,或是“对于阴蒂的不正常刺激”会造成耻骨神经末梢的兴奋,会造成歇斯底里、脊髓刺激、痉挛、白痴、癫狂甚至死亡”[175]。依照在1873年《医疗时报公报》中讣闻中提到内容,“只要他有机会,就会动手切除阴蒂。”[176]布朗医生在1859年到1866之间进行了多次的阴蒂切除手术。他后来发表了《对女性某些形式的精神错乱,癫痫,僵住症,和歇斯底里的可治愈性》(1866年),伦敦的医师指责他是骗子,并将他赶出伦敦产科协会[177]。

美国的J.·马里恩·西姆斯延续了布朗医师的研究,在1862年在一名女性病患主诉经痛、抽搐和膀胱问题后,切开其子宫颈,并且切除阴蒂,“用布朗医师建议的方式来缓解紧张及歇斯底里的状态。”[178]。在同一世纪,纽奥兰的外科医生A. J. Bloch因一名二岁的女童持续性的自慰,切除其阴蒂[179]。依照1985年产科和妇科调查的论文,1960年代美国还有用切除阴蒂来治疗歇斯底里,色情狂和女同性恋[180]。

反对声浪

Muthirigu

小刀在鞘中

他们会和教会对抗

时候到了

(教会的)长者啊

当肯尼亚塔来的时候

他会给你们女生的衣服

你们要为他作饭

基库尤人舞蹈时的歌曲,对抗教会对于残割女性生殖器的反对[181]

二十世纪初,约翰·阿瑟加入在英属东非(现今肯尼亚)基库尤的苏格兰福音会(CSM)服事,新教传教士当时就开始反对女性割礼的活动。基库尤人是肯尼亚的主要族群,他们称男性及女性的割礼为irua,男性是割除包皮,女性则是类型二的残割女性生殖器(部分或全部切除小阴唇),这是基库尤人重要的族群记号,没有实行割礼的女性称为irugu,会被逐出社群之外[182]

乔莫·肯雅塔是基库尤中央联盟的主席及1963年起的首任肯尼亚总理,他在1938年提到,对于基库尤人而言,女性割礼的规定:“是整个部落法律、宗教及道德中,不可缺少的条件”(conditio sine qua non)。没有一个正常的基库尤人会和没有行割礼的人发生性关系或结婚。女性对部落的责任从她的成年礼开始。她在部落历史中的记录会从这一天开始,部落会依当时的事件为受割礼的女性命名,这是基库尤的口头传统,让基库尤人可以追溯上百年前的人物及事件[183]。

1925年起,苏格兰福音会开始宣布非洲的基督徒禁止进行残割女性生殖器,许多非洲的宣教机构也有类似的声明。苏格兰福音会宣布进行残割女性生殖器的非洲人会被逐出教会,因此有上百人离开教会或是被赶出教会[184]。这样的对峙使得残割女性生殖器成为肯尼亚独立运动的焦点,肯尼亚在1929年至1931年有 1929年至1932年肯尼亚反对残割女性生殖器运动[185],殖民政府及教会反对残割女性生殖器,而基库尤人反对殖民政府及教会的作法。

1929年肯尼亚宣教协会开始认为残割女性生殖器不是割礼,而是“对女性的性残害”,而个人是否进行残割女性生殖器也就代表他忠于基督教会或是忠于基库尤中央联盟[186]。霍尔达·史敦夫是非洲内地会的美国宣教士,在她协助成立的女子学校中反对残割女性生殖器,在1930年被谋杀。肯尼亚总督爱德华·格里格告诉肯尼亚殖民地办公室说,凶手试图要为史敦夫进行残割女性生殖器[187]。

1956年时梅鲁族长老协会(Njuri Nchecke)宣布禁止残割女性生殖器。然而此举却引起族人反抗,之后的三年内,数千名少女用小刀为彼此进行残割女性生殖器。这个活动在梅鲁族称为“Ngaitana”(自行割礼),如此命名是因为虽然手术是由女孩的朋友所执行,但为了避免提及操刀者的名字,女孩会说是他们自己动刀的。历史学家莱恩·汤玛斯(Lynn Thomas)将这个视为是残割女性生殖器历史中的重要内容,因为清楚的看出残割女性生殖器的受害者也成为了加害者[188]

1920年代在埃及展开反对残割女性生殖器的活动,这是目前已知第一场不是由殖民政府或是传教士发起的反对残割女性生殖器活动。当时埃及医师社群号召禁止残割女性生殖器[189],同时苏丹的宗教领袖及英籍妇女也响应活动。苏丹在1946年禁止锁阴术,但这条法律执行成效向来不彰[190][w]。埃及政府在1959年在州营医院禁止锁阴术,但却允许在双亲要求下执行部分阴蒂切除术[192][x]

联合国在1959年要求世界卫生组织调查残割女性生殖器,但世界卫生组织回应这不是医疗相关议题[193]。女性主义者在1970年代开始提出此一议题[194]。埃及女医生纳瓦勒·萨达在1972年出版的《女人与性》(Women and Sex)中批评残割女性生殖器,这本书在埃及是禁书,她也因为失去了公共卫生总干事的工作[195]。她在1980年出版的《夏娃隐藏的脸:阿拉伯世界的女性》(The Hidden Face of Eve: Women in the Arab World)中〈女孩的割礼〉一节中描述她自己在六岁时接受阴蒂切除术的情形:

我不知道他们从我身上切除了什么,我没有去找。我只是哭,向我的妈妈呼唤求助。但最令人惊吓的是我环顾四周,发现她就站在我身边,是的,就是她,我没有弄错,身为我的妈妈,站在这一群陌生人之间,和他们微笑及说话,就好像他们几分钟前没有参与杀害她女儿的行动一样[196]。

1975年时,美国社会科学家罗斯·欧德菲尔德·海耶斯(Rose Oldfield Hayes)发表残割女性生殖器相关记录,她是第一位发表这类记录的女性学者,她是在和苏丹的女性直接讨论此议题后,得到有关资料。她在《美国民族学家》期刊发表的论文中,称这种习俗为“残割女性生殖器”(female genital mutilation),带来学术界更广泛的注意[197]。

四年之后的1979年,奥地利裔美籍的女性主义者弗兰·霍斯肯出版了《霍斯肯报告:女性生殖器及性器官残割》(The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females,1979)。霍斯肯在此本著作中估计,全球约有110,529,000名女性实施过残割女性生殖器,分布于20个非洲国家[198]。这是第一篇提出残割女性生殖器实施人数的文献,该数据虽为估计值,但后来进行的几次调查也大略符合此数字。Mackie认为霍斯肯的著作虽然对于数据与资料来源稍嫌不严谨,但唤醒世界对于此议题的重视[199]。霍斯肯用“男性暴力的训练场”来描述残割女性生殖器,将其中女性的参与者称为是“参与了毁灭同类的活动”[200]。这段话造成西方及非洲女性主义者之间的冲突。联合国在1980年7月于哥本哈根举行的十年中期会议,非洲女性主义者就杯葛其中一个以霍斯肯为主题的会议[201]。

在1979年,世界卫生组织在苏丹喀土木举办“传统习俗影响妇女与孩童健康研讨会”,1981年巴拜克巴德里妇女研究科学协会(BBSAWS)也在喀土木举办了三天的研习营“携手对抗女性割礼对女性造成的残疾与危害”(Female Circumcision Mutilates and Endangers Women – Combat it!) 。活动结束后有150位学者与活跃人士签署,宣示对抗残割女性生殖器。另一个巴拜克巴德里妇女研究科学协会在1984年举办的研习营,其中邀请国际社群,签署给联合国的联合声明。签署者同意他们在联合声明中所写到的“女性割礼是对人权的暴力,侵犯女性的尊严,剥夺女性的性欲,并且是对于女性健康的无端羞辱。”[202]其中包括了:

- 建议非洲女性完全根除女性割礼相关手术。

- 禁绝所有实务上有关残割女性生殖器的信仰内涵,如将切除阴蒂视为“圣训”等等。

- 应设计替代仪式,现在一般会称为“替代式成人礼”[203]

泛非洲影响妇女及儿童的传统医疗实务协会1984年成立于塞内加尔的达喀尔,此协会呼吁中止女性割礼这项习俗,1993年在维也纳举办的联合国世界人权会议也提出类似诉求。这次会议将残割女性生殖器列为对妇女的暴力行为,并认定此议题是违反人权的议题,不只是医学议题而已[204]。在1990年代到2000年年代,非洲政府严惩或是限制女性割礼。在2003年七月,非洲联盟批准了马普拖协议中关于女权的部分,支持禁绝残割女性生殖器[205]。截至2015年,27个实行残割女性生殖器的非洲国家中,至少有23个通过禁止法令,不过少数国家仍未完全禁止[y]。

联合国大会 于1993年12月提出的48/104决议案,亦即《消除对妇女的暴力行为宣言》,就包含了残割女性生殖器。联合国在2003年起,将每年2月6日订为残割女性生殖器国际零容忍日[208]。同年,联合国儿童基金会(UNICEF)开始推广以Gerry Mackie发展的实证性社会规范方法评估介入行为。Gerry 在对于中国如何放弃缠足的习俗研究中,利用赛局理论推估社群究竟如何取得最终共识,而UNICEF也利用此一研究的基础来进行分析FGM[209],并于2005年,在佛罗伦萨的因诺琴蒂研究中心发表该组织的第一份相关研究报告[210]。

2008年,联合国人权事务高级专员办事处等多个联合国组织在内,共同发表了一份声明,认定残割女性生殖器是对人权的侵犯[211]。在2012年12月时,联合国大会通过67/146号决议,要求致力消除残割女性生殖器[17]。而在2014年7月联合国儿童基金会和英国政府共同主办了第一届女童高峰会(Girl Summit),目标为结束残割女性生殖器和童婚的习俗[212]。

2007年,联合国人口基金(UNFPA) 和 UNICEF 发起一项联合计划,旨在使15岁以下少女进行残割女性生殖器的比例减少四成,并使至少一个国家根绝该习俗。在2008年参与该计划的国家共15国,包含:吉布提、埃及、埃塞俄比亚、几内亚、几内亚比绍、肯尼亚、塞内加尔,和苏丹。隔年,普吉内法索、冈比亚、索马里和乌干达加入;2011年,马里、厄立特里亚、毛里塔尼亚也加入该计划[213]。该计划的第一阶段从2008年到2013年为止,投入了近3700万美金,当中有2000亿的资金是由挪威捐献[214]。第二期则由2014年至2017年[215]。

2013年的计划中已经让12,753个社区宣布不进行残割女性生殖器,整合了5,571个关于残割女性生殖器的先天与后天的照护预防治疗的卫生设施,并且培训了超过10万个在照护与预防残割女性生殖器相关领域的医生,护士以及助产士。这项计划帮助了建置乌干达与肯尼亚的通过仪式替代方案,并在苏丹支援了早已存在的儿童保护计划的 Saleema 行动。Saleema 在阿拉伯文的意思是"完整",这个行动促使了这个名词成为对尚未施行残割女性生殖器女性的完整表述[216]。此计划也注意到反残割女性生殖器的执法成效薄弱,即使有进行逮捕,也会因为检查机关取证的不充份而失效[217]。因此这个计划在八个国家(吉布提、厄立特里亚、埃塞俄比亚、几内亚、几内亚比绍、肯尼亚、塞内加尔和乌干达)培训了3011人执行相关法律,并且支援相关宣传,提升当地的意识[218]。

截至2013年[update]为止,在非洲及中东以外的国家,已有33个国家立法禁止残割女性生殖器[206]。残割女性生殖器由移民带入澳大利亚、新西兰、欧洲、北美、斯堪的纳维亚半岛等地;这些地区立法禁止残割女性生殖器[z][220]。而在1982年颁布禁令的瑞典,成为第一个对于残割女性生殖器做出法规限制的西方国家[221]。前殖民列强如比利时、英国、法国、荷兰等国也随后进行立法禁止,或是做出声明厘清该手术违反现行法条[222]。

加拿大于1994年7月授予来自索马里的卡德拉·哈桑·法拉赫难民身份时,即认定残割女性生殖器是一种对女性的迫害[223];卡德拉·哈桑·法拉赫在加拿大避难以避免她的女儿遭受残割女性生殖器之苦。加拿大政府于1997年修改加拿大刑法法典268条法条中的部分法条,明令禁止残割女性生殖器,但若接受手术之人已满18岁且没有因此造成身体伤害则不在禁止范围内[224]。截止至2015年2月,仍未有针对残割女性生殖器的诉讼[225]。

美国疾病控制与预防中心(CDC在1997年时预估,在1990年时美国有16.8万名女性经历过残割女性生殖器或是在这样的风险当中[226]。据美国疾病控制与预防中心2015年的一份初步且未公开的研究预测,美国大约有50万名女性曾经历过残割女性生殖器,或是有可能经历过残割女性生殖器[227]。1994年3月,一名尼日尔的女性因其女有可能遭受残割女性生殖器之苦成功抗辩美国政府驱逐出境的命令[228]。另外,于1996年来自多哥共和国的法西亚·卡辛嘉成为美国第一位因为逃避残割女性生殖器就而取得庇护的女性[229]。不过截至2006年为止,一些联邦上诉法庭主张父母不应因害怕其子女遭受残割女性生殖器为理由接受庇护,尤其是在案中儿童是美国合法居民或公民的情况下[230]。

1996年美国法典第18卷116条将以非医疗目的对未成年少女施行残割女性生殖器定义为非法行为[231],2013年美国国防授权法案禁止以残割女性生殖器为目的将未成年人运送出国[232]。美国小儿科学会反对任何形式的残割女性生殖器。小儿科学会于2010年提出“针刺或切割阴蒂的皮肤”没有危害且可以满足父母要求,但在遭投诉后撤回了此说法[233]。美国首例残割女性生殖器定罪案是在2006年,一位埃塞俄比亚移民哈立德·阿德姆因为以剪刀切除两岁女儿的阴蒂而被判处十年徒刑[234]。

欧洲议会称欧洲截至至截至2009年3月[update]时有近50万名妇女受过残割女性生殖器[236]。法国考虑到移民的同化对法国民族身份与团结至关重要,因此以严厉对待残割女性生殖器出名。[237]。法国有大约三万名妇女经历过残割女性生殖器。家庭计划辅导员科莱特·加勒德写到:残割女性生殖器首次在法国出现时,公众的反应是西方人不要干预此事;直到1982年两名女童因残割女性生殖器死亡后(其中一名三个月大)公众看法才得到改变[238]。法国刑法中涉及儿童暴力的条款禁止残割女性生殖器[239]。所有在法国出生的儿童在六岁之前需要进行包括检查生殖器在内的体检;医生若检查到残割女性生殖器,有义务举报[237]。1982年法国出现了首宗关于残割女性生殖器的民事诉讼,1993年出现了首宗刑事诉讼[240]。1999年一名女性因为对48位女孩施行残割女性生殖器而被判八年徒刑[241]。截至2014年,在超过四十宗刑事案件中起诉了超过一百名父母及两位从事残割女性生殖器的人员[237][239]。

在2011年约13.7万名居住在英格兰与威尔士地区的女性,出生于施行残割女性生殖器的国家[242]。1985年,英国颁布相关禁令禁止对儿童或成人实施残割女性生殖器[243]。该法案被2003年残割女性生殖器法案与2005年苏格兰禁止残割女性生殖器法案取代,新法案中进一步禁止将英国公民或永久居民带出国外实行残割女性生殖器的行为[244][aa]。联合国消除对妇女一切形式歧视公约在2013年要求各国政府“务必在立法上完整规范残割女性生殖器”[246]。次年有一男子与一医生被起诉;该医生将一名曾受残割女性生殖器的妇女阴部打开后重新缝合。2015年两人无罪获释[247]。

对反对意见的评论

人类学家埃里克·西尔弗曼于2004年写到,她认为残割女性生殖器已成为“当代人类学中最重要的道德议题之一”。

一些文化价值观严重扭曲的人类学家们指控“支持废除残割女性生殖器者”为文化殖民主义者;相对地,这些人类学家也因为所持的道德相对主义及未能成功捍卫人权普世概念而被批评[248]。根据针对反对方的批评,认为反对方所提的生物还原论、不认同残割女性生殖器背后的文化价值,逐渐在削弱施行残割的机制,并以此将其边缘化——尤其是借由称呼非洲籍父母是“残割者”(mutilator) [249]。但不认同反对方意见的非洲人们,似乎仍捍卫残割女性生殖器的实行[250]。女权主义理论家欧比欧玛·那亚米卡——她个人极反对残割女性生殖器,主张“没有一位女性应被施行割礼。”[ab],但她认为将“女性割礼”重新命名为“残割女性生殖器”(female genital mutilation)的影响是不可低估的:

在这场命名游戏中,虽然讨论的是非洲女性,却隐含着西方文明与试图涤净所谓野蛮的非洲文化和穆斯林文化的关联性(甚至是必要性),这标志着殖民主义和传教士热衷于(zeal)定义何谓“文明”,并想着如何及何时要强迫没有要求得到这些的人们接受这一切[252]

乌干达法学教授西尔维亚·塔马利认为早期西方世界对于残割女性生殖器的反对声浪来自于犹太教-基督教价值观,他们认为非洲社会的家庭价值和性观念是原始且必须矫治的,包含干阴道性交、一夫多妻制、聘礼,以及夫兄弟婚等等[253]。塔马利表示,非洲女权主义者“不容忍这些非洲世界传统举措产生的负面影响”,却“完全容忍帝国主义、种族歧视,以及对于非洲女性的稚化鄙视。”[253]

人类学者和女权主义者一直对于残割女性生殖器的存废争论不休,盖因人类学者主要关注陋习容忍性,而女权主义者则聚焦于普世性的平等女权。人类学家克莉丝汀·瓦莱写道,1970年代至1980年代之间,弗兰·霍斯肯、玛丽·戴莉,和汉妮·莱特富特-克莱恩(Hanny Lightfoot-Klein)等女权主义者推动反残割女性生殖器运动时,声援的文学家利用浅显的比喻,将非洲女性形塑为因虚假意识影响,而参与对自己身体进行迫害的受害者形象。这促使法国人类学学会于1981年声明立场,当时是残割女性生殖器前期论战的最高峰。声明表示“今日的女权主义,实则昨日殖民主义者教条式的礼教。”[254]

另外有一些人认为,部分行为对实施过残割女性生殖器手术的女性相当不敬,展示她们身体及阴部的照片。历史学家Chima Korieh以1996年普利策奖得主Stephanie Welsh的得奖作品为例,该照片以一名正在接受残割女性生殖器的肯尼亚女孩做为题材,并被12家美国媒体刊登,然而根据Korieh的说法,那名肯尼亚女孩根本没有同意Welsh的拍摄,更遑论是刊登[255]

欧毕欧马·内梅卡(Obioma Nnaemeka)提出一个比起残割女性生殖器更广泛的重要议题:为什么包含西方国家在内,全世界有那么多地方“虐待及污化”女性身体的举措[256]?许多作家将残割女性生殖器与整形手术提出来做比较[257]爱尔兰皇家外科医学院的罗南·康罗伊在2006年写到生殖器整形手术“驱动著女性生殖器残割前进”,因其鼓励女性将自然个体上的差异视为缺陷[258]。人类学家法德瓦·拉·金蒂将残割女性生殖器与隆乳互相比较,因为乳房具有的哺育功能竟然次于取悦男性性快感[259]。博奴瓦特·格鲁在1975年提出类似的论点,点出残割女性生殖器与整形手术并将其视为男性沙文主义与父系社会的威权[260]。

卡拉·欧巴玛雅主张残割女性生殖器有助于女性与社群好好相处,隆鼻与男性割包皮也有相同的道理[261]在埃及,尽管在2007年对残割女性生殖器下了禁令,女性想让自己的女儿进行残割女性生殖器,因此讨论需要借由amalyet tajmeel(外科整形手术)来移除看起来多余的外生殖组织,让阴部有比较能够接受的外型[262]。

世界卫生组织并不将阴唇整型术及去除阴蒂包皮视为残割女性生殖器,但它的定义是为了防止漏洞的产生,而确实有许多对于成人的作法都不在世界卫生组织的分类中[263]。有些禁止残割女性生殖器的国家只着重在未成年者,像是加拿大和美国。包括瑞典和英国在内的许多国家,立法禁止任何与残割女性生殖器有关的手术,甚至涵盖到整形手术。以瑞典来说,“无论受术者是否同意手术的进行,瑞典政府都禁止切除或会对女性外部生殖器官产生永久性变化的手术”[264]。妇产科医生彼吉妲·艾森(Birgitta Essén)和人类学家莎拉·琼斯达特(Sara Johnsdotter)提到,在法律上似乎可以显示西方国家和非洲地区对于阴部的观念差异,且非洲的女性(尤其在产后寻求再缝阴手术的妇女)不太容易自行做出手术选择的决定[265]。

有些人质疑,残割女性生殖器和女孩为了体态而节食有什么不同?哲学家玛莎·努斯鲍姆认为此两者最大的差异在于,接受残割女性生殖器的女孩通常是被硬生生的抓去接受手术。她以色诱和强暴互相比较,认为相较于前述的物理性胁迫,女孩因社会眼光的压力而进行节食,于道德和法律上相对有理据。此外,玛莎又做了一些延伸探讨,认为实行残割女性生殖器的国家,大部分识字率和发展程度较低,而影响了女性受知的机会,这使她们选择的能力大幅降低[266]。

一些评论者认为双性人孩子的生殖器改变手术侵犯了儿童的人权,这些孩子一出生因为拥有双性生殖器而被医生诊断修正。法律学者南希·厄莱雷奇(Nancy Ehrenreich)和马克·巴尔(Mark Barr)表示上述案例有数千件在美国发生,并说道这在医学上是不必要,但比残割女性生殖器更广泛,且在生理与心理上有严重的后果。他们归因于反残割女性生殖器运动者因白人特权,对于双性者的漠视,与一种拒绝承认“类似且不必要和有害的生殖器切割就发生在自家后院。”[267]。

参见

脚注

参考资料

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.