Loading AI tools

Robert Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a prolific English poet, scholar and novelist. He is most famous for his autobiographical work Goodbye to All That, and works on classical themes and mythology, such as I, Claudius, The Greek Myths and The White Goddess. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves.

General sources

- The dead may speak the truth only, even when it discredits themselves.

- The Golden Fleece (1944), Invocation

- To be a poet is a condition rather than a profession.

- Reply to questionnaire, "The Cost of Letters" in Horizon (September 1946)

- I believe that every English poet should read the English classics, master the rules of grammar before he attempts to bend or break them, travel abroad, experience the horror of sordid passion and — if he is lucky enough — know the love of an honest woman.

- Lecture at Oxford as quoted in Time (15 December 1961)

- Anthropologists are a connecting link between poets and scientists; though their field-work among primitive peoples has often made them forget the language of science.

- "Mammon" an address at the London School of Economics (6 December 1963); published in Mammon and the Black Goddess (1965)

- The remarkable thing about Shakespeare is that he is really very good — in spite of all the people who say he is very good.

- Quoted in The Observer [London] (6 December 1964)

- A perfect poem is impossible. Once it had been written, the world would end.

- The Paris Review, "Writers at Work: 4th series," interview with Peter Buckman and William Fifield (1969)

- Philosophy is antipoetic. Philosophize about mankind and you brush aside individual uniqueness, which a poet cannot do without self-damage. Unless, for a start, he has a strong personal rhythm to vary his metrics, he is nothing. Poets mistrust philosophy. They know that once the heads are counted, each owner of a head loses his personal identity and becomes a number in some government scheme: if not as a slave or serf, at least as a party to the device of majority voting, which smothers personal views.

- "The Case for Xanthippe" in The Crane Bag (1969)

- Abstract reason, formerly the servant of practical human reasons, has everywhere become its master, and denies poetry any excuse for existence.

Though philosophers like to define poetry as irrational fancy, for us it is practical, humorous, reasonable way of being ourselves. Of never acquiescing in a fraud; of never accepting the secondary-rate in poetry, painting, music, love, friends. Of safeguarding our poetic institutions against the encroachments of mechanized, insensate, inhumane, abstract rationality.- "The Case for Xanthippe" in The Crane Bag (1969)

- Even nowadays an archaic sense of love-innocence recurs, however briefly, among most young men and women. Some few of these, who become poets, remain in love for the rest of their lives, watching the world with a detachment unknown to lawyers, politicians, financiers, and all other ministers of that blind and irresponsible successor to matriarchy and patriarchy — the mechanarchy.

- Introduction Poems about Love (1969)

- If I were a girl, I'd despair. The supply of good women far exceeds that of a man who desrves them.

- Robert Graves Quotes. (n.d.). BrainyQuote.com. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

Poems

Thirsting and hungering,

Walked in the wilderness;

Soft words of grace He spoke

Unto lost desert-folk

That listened wondering.

The trivial skirmish fought near Marathon.

Do not forget what flowers

The great boar trampled down in ivy time...

Heedless of where the next bright bolt may fall.

- Trench stinks of shallow buried dead

Where Tom stands at the periscope,

Tired out. After nine months he’s shed

All fear, all faith, all hate, all hope.- "Through the Periscope" (1915) [first published in 1988]

- Christ of His gentleness

Thirsting and hungering,

Walked in the wilderness;

Soft words of grace He spoke

Unto lost desert-folk

That listened wondering.- "In the Wilderness," lines 1-6, from Over the Brazier (1916), Part I: Poems Written Mostly at Charterhouse 1910-1914

- His eyes are quickened so with grief,

He can watch a grass or leaf

Every instant grow; he can

Clearly through a flint wall see,

Or watch the startled spirit flee

From the throat of a dead man.- "Lost Love," lines 1-6, from Treasure Box (1919)

- There’s a cool web of language winds us in,

Retreat from too much joy or too much fear:

We grow sea-green at last and coldly die

In brininess and volubility.- "The Cool Web," lines 9–12, from Poems 1914-1926 (1927)

- As you are woman, so be lovely:

As you are lovely, so be various,

Merciful as constant, constant as various,

So be mine, as I yours for ever.- "Pygmalion to Galatea" from Poems 1914-1926 (1927)

Be warm, enjoy the season, lift your head,

Exquisite in the pulse of tainted blood,

That shivering glory not to be despised.Take your delight in momentariness,

Walk between dark and dark — a shining space

With the grave’s narrowness, though not its peace.- "Sick Love," lines 7–12, from Poems 1929

- Children, if you dare to think

Of the greatness, rareness, muchness,

Fewness of this precious only

Endless world in which you say

You live, you think of things like this:

Blocks of slate enclosing dappled

Red and green, enclosing tawny

Yellow nets, enclosing white

And black acres of dominoes,

Where a neat brown paper parcel

Tempts you to untie the string.- "Warning to Children," lines 1–11, from Poems 1929 (1929)

- Down, wanton, down! Have you no shame

That at the whisper of Love’s name,

Or Beauty’s, presto! up you raise

Your angry head and stand at gaze?- "Down, Wanton, Down!," lines 1-4, from Poems 1930-1933 (1933)

- To the much-tossed Ulysses, never done

With woman whether gowned as wife or whore,

Penelope and Circe seemed as one:

She like a whore made his lewd fancies run,

And wifely she a hero to him bore.- "Ulysses" from Poems 1930-1933 (1933)

- They multiplied into the Sirens' throng,

Forewarned by fear of whom he stood bound fast

Hand and foot helpless to the vessel's mast,

Yet would not stop his ears: daring their song

He groaned and sweated till that shore was past.- "Ulysses" from Poems 1930-1933 (1933)

- One, two and many: flesh had made him blind,

Flesh had one pleasure only in the act,

Flesh set one purpose only in the mind —

Triumph of flesh and afterwards to find

Still those same terrors wherewith flesh was racked.- "Ulysses," lines 16–20, from Poems 1930-1933 (1933)

- His wiles were witty and his fame far known,

Every king's daughter sought him for her own,

Yet he was nothing to be won or lost.

All lands to him were Ithaca: love-tossed

He loathed the fraud, yet would not bed alone.- "Ulysses" from Poems 1930-1933 (1933)

- Sigh then, or frown, but leave (as in despair)

Motive and end and moral in the air;

Nice contradiction between fact and fact

Will make the whole read human and exact.- "The Devil’s Advice to Story-tellers," lines 19–22, from Collected Poems 1938 (1938)

- Entrance and exit wounds are silvered clean,

The track aches only when the rain reminds.

The one-legged man forgets his leg of wood,

The one-armed man his jointed wooden arm.

The blinded man sees with his ears and hands

As much or more than once with both his eyes.- "Recalling War," lines 1–6, from Collected Poems 1938 (1938)

- What, then, was war? No mere discord of flags

But an infection of the common sky

That sagged ominously upon the earth.- "Recalling War," lines 11–13, from Collected Poems 1938 (1938)

- War was return of earth to ugly earth,

War was foundering of sublimities,

Extinction of each happy art and faith

By which the world had still kept head in air.- "Recalling War," lines 31–34, from Collected Poems 1938 (1938)

- Truth-loving Persians do not dwell upon

The trivial skirmish fought near Marathon.- "The Persian Version," lines 1–2, from Poems 1938-1945: Satires and Grotesques (1946)

- There is one story and one story only

That will prove worth your telling,

Whether as learned bard or gifted child;

To it all lines or lesser guards belong

That startle with their shining

Such common stories as they stray into.- "To Juan at the Winter Solstice" from Poems 1938-1945 (1946)

- Water to water, ark again to ark,

From woman back to woman:

So each new victim treads unfalteringly

The never altered circuit of his fate,

Bringing twelve peers as witness

Both to this starry rise and starry fall.- "To Juan at the Winter Solstice" from Poems 1938-1945 (1946)

- She in left hand bears a leafy quince;

When with her right she crooks a finger, smiling,

How may the King hold back?

Royally then he barters life for love.- "To Juan at the Winter Solstice" from Poems 1938-1945 (1946)

- Fear in your heart cries to the loving-cup:

Sorrow to sorrow as the sparks fly upward.

The log groans and confesses

There is one story and one story only.- "To Juan at the Winter Solstice" from Poems 1938-1945 (1946)

- Dwell on her graciousness, dwell on her smiling,

Do not forget what flowers

The great boar trampled down in ivy time.

Her brow was creamy as the crested wave,

Her sea-blue eyes were wild

But nothing promised that is not performed.- "To Juan at the Winter Solstice," lines 37–42, from Poems 1938-1945 (1946)

- All saints revile her, and all sober men

Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean —

In scorn of which we sailed to find her

In distant regions likeliest to hold her

Whom we desired above all things to know,

Sister of the mirage and echo.- "The White Goddess," lines 1–6, from Poems and Satires (1951)

- But we are gifted, even in November,

Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense

Of her nakedly worn magnificence

We forget cruelty and past betrayal,

Heedless of where the next bright bolt may fall.- "The White Goddess," lines 18–22, from Poems and Satires (1951)

- Love is a universal migraine.

A bright stain on the vision

Blotting out reason.- "Symptoms of Love," lines 1-3, from More Poems (1961)

- Take courage, lover!

Could you endure such pain

At any hand but hers?- "Symptoms of Love" from More Poems (1961)

Fairies and Fusiliers (1917)

- The holiest, cruellest pains I feel,

Die stillborn, because old men squeal

For something new: "Write something new:

We've read this poem — that one too,

And twelve more like 'em yesterday"?- "To An Ungentle Critic"

What wrong they say we're righting,

A curse for treaties, bonds and laws,

When we're to do the fighting!

- It doesn't matter what's the cause,

What wrong they say we're righting,

A curse for treaties, bonds and laws,

When we're to do the fighting!- "To Lucasta on Going to the War — For the Fourth Time"

And so decide who started

This bloody war, and who's to pay...

- Let statesmen bluster, bark and bray,

And so decide who started

This bloody war, and who's to pay,

But he must be stout-hearted,

Must sit and stake with quiet breath,

Playing at cards with Death.

Don't plume yourself he fights for you;

It is no courage, love, or hate,

But let us do the things we do;

It's pride that makes the heart be great;

It is not anger, no, nor fear —

Lucasta he's a Fusilier,

And his pride keeps him here.- "To Lucasta on Going to the War — For the Fourth Time"

- The child alone a poet is:

Spring and Fairyland are his.

Truth and Reason show but dim,

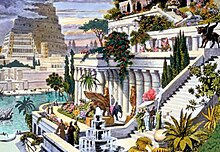

And all's poetry with him.- "Babylon"

- Wisdom made him old and wary

Banishing the Lords of Faery.

Wisdom made a breach and battered

Babylon to bits: she scattered

To the hedges and ditches

All our nursery gnomes and witches.- "Babylon"

- Robin, and Red Riding Hood

Take together to the wood,

And Sir Galahad lies hid

In a cave with Captain Kidd.

None of all the magic hosts,

None remain but a few ghosts

Of timorous heart, to linger on

Weeping for lost Babylon.- "Babylon"

In these verses that you've read.

Spring again from hidden roots

Pull or stab or cut or burn,

Love must ever yet return.

- When a dream is born in you

With a sudden clamorous pain,

When you know the dream is true

And lovely, with no flaw nor stain,

O then, be careful, or with sudden clutch

You'll hurt the delicate thing you prize so much.- "A Pinch of Salt"

- Poet, never chase the dream.

Laugh yourself and turn away.

Mask your hunger, let it seem

Small matter if he come or stay;

But when he nestles in your hand at last,

Close up your fingers tight and hold him fast.- "A Pinch of Salt"

- Through the window I can see

Rooks above the cherry-tree,

Sparrows in the violet bed,

Bramble-bush and bumble-bee,

And old red bracken smoulders still

Among boulders on the hill,

Far too bright to seem quite dead.

But old Death, who can't forget,

Waits his time and watches yet,

Waits and watches by the door.- "The Cottage"

- When I'm killed, don't think of me

Buried there in Cambrin Wood,

Nor as in Zion think of me

With the Intolerable Good.

And there's one thing that I know well,

I'm damned if I'll be damned to Hell!- "When I'm Killed"

- So when I'm killed, don't wait for me,

Walking the dim corridor;

In Heaven or Hell, don't wait for me,

Or you must wait for evermore.

You'll find me buried, living-dead

In these verses that you've read.- "When I'm Killed"

Never need for shirt or frock,

Never want for food or fire,

Always get their heart's desire...

- Children born of fairy stock

Never need for shirt or frock,

Never want for food or fire,

Always get their heart's desire...- "I'd Love To Be A Fairy's Child"

- Every fairy child may keep

Two strong ponies and ten sheep;

All have houses, each his own,

Built of brick or granite stone;

They live on cherries, they run wild —

I'd love to be a Fairy's child.- "I'd Love To Be A Fairy's Child"

- Another War soon gets begun,

A dirtier, a more glorious one;

Then, boys, you'll have to play, all in;

It's the cruellest team will win.

So hold your nose against the stink

And never stop too long to think.

Wars don't change except in name;

The next one must go just the same,

And new foul tricks unguessed before

Will win and justify this War.- "The Next War"

- Kaisers and Czars will strut the stage

Once more with pomp and greed and rage;

Courtly ministers will stop

At home and fight to the last drop;

By the million men will die

In some new horrible agony...- "The Next War"

- With a fork drive Nature out,

She will ever yet return;

Hedge the flowerbed all about,

Pull or stab or cut or burn,

She will ever yet return.- "Marigolds"

- New beginnings and new shoots

Spring again from hidden roots

Pull or stab or cut or burn,

Love must ever yet return.- "Marigolds"

- Let Cupid smile and the fiend must flee;

Hey and hither, my lad.- "Love and Black Magic"

Country Sentiment (1920)

The form and measure of that vast God we call Poetry, he who stoops and leaps me through his paper hoops a little higher every time.

- I do not love the Sabbath,

The soapsuds and the starch,

The troops of solemn people

Who to Salvation march.

I take my book, I take my stick

On the Sabbath day,

In woody nooks and valleys

I hide myself away.

To ponder there in quiet

God's Universal Plan,

Resolved that church and Sabbath

Were never made for man.- "The Boy out of Church"

- Now I begin to know at last,

These nights when I sit down to rhyme,

The form and measure of that vast

God we call Poetry, he who stoops

And leaps me through his paper hoops

A little higher every time.- "The God Called Poetry"

- He is older than the seas,

Older than the plains and hills,

And older than the light that spills

From the sun's hot wheel on these.

He wakes the gale that tears your trees,

He sings to you from window sills.- "The God Called Poetry"

- Riding on the shell and shot.

He smites you down, he succours you,

And where you seek him, he is not.- "The God Called Poetry"

- Immeasurable at every hour:

He first taught lovers how to kiss,

He brings down sunshine after shower,

Thunder and hate are his also,

He is YES and he is NO.- "The God Called Poetry"

- Then speaking from his double head

The glorious fearful monster said

"I am YES and I am NO,

Black as pitch and white as snow,

Love me, hate me, reconcile

Hate with love, perfect with vile,

So equal justice shall be done

And life shared between moon and sun.

Nature for you shall curse or smile:

A poet you shall be, my son."- "The God Called Poetry"

- Lovers to-day and for all time

Preserve the meaning of my rhyme:

Love is not kindly nor yet grim

But does to you as you to him.- "Advice To Lovers"

Stoops and kneels and grovels, chin to the mud.

- Then all you lovers have good heed

Vex not young Love in word or deed:

Love never leaves an unpaid debt,

He will not pardon nor forget.- "Advice To Lovers"

- Down on his knees he sinks, the stiff-necked King,

Stoops and kneels and grovels, chin to the mud.

Out from his changed heart flutter on startled wing

The fancy birds of his Pride, Honour, Kinglihood.

He crawls, he grunts, he is beast-like, frogs and snails

His diet, and grass, and water with hand for cup.

He herds with brutes that have hooves and horns and tails,

He roars in his anger, he scratches, he looks not up.- "Nebuchadnezzar's Fall"

Worth very little,

Yet I suck at my long pipe

At peace in the sun,

I do not fret nor much regret

That my work is done.

- I am an old man

With my bones very brittle,

Though I am a poor old man

Worth very little,

Yet I suck at my long pipe

At peace in the sun,

I do not fret nor much regret

That my work is done.- "Brittle Bones"

- If I were a young man

And young was my Lily,

A smart girl, a bold young man,

Both of us silly.

And though from time before I knew

She'd stab me with pain,

Though well I knew she'd not be true,

I'd love her again.- "Brittle Bones"

- If I were a young man

With my bones full of marrow,

Oh, if I were a bold young man

Straight as an arrow,

I'd store up no virtue

For Heaven's distant plain,

I'd live at ease as I did please

And sin once again.- "Brittle Bones"

- And what of home — how goes it, boys,

While we die here in stench and noise?- "Country At War"

Man is but grass and hate is blight,

The sun will scorch you soon or late,

Die wholesome then, since you must fight.

- Where nature with accustomed round

Sweeps and garnishes the ground

With kindly beauty, warm or cold —

Alternate seasons never old:

Heathen, how furiously you rage,

Cursing this blood and brimstone age,

How furiously against your will

You kill and kill again, and kill:

All thought of peace behind you cast,

Till like small boys with fear aghast,

Each cries for God to understand,

'I could not help it, it was my hand.'"- "Country At War"

Strike with no madness when you strike.

- Kill if you must, but never hate:

Man is but grass and hate is blight,

The sun will scorch you soon or late,

Die wholesome then, since you must fight.- "Hate Not, Fear Not"

- Hate is a fear, and fear is rot

That cankers root and fruit alike,

Fight cleanly then, hate not, fear not,

Strike with no madness when you strike.- "Hate Not, Fear Not"

- Love, Fear and Hate and Childish Toys

Are here discreetly blent;

Admire, you ladies, read, you boys,

My Country Sentiment.- "A First Review"

- Hate and Fear are not wanted here,

Nor Toys nor Country Lovers,

Everything they took from my new poem book

But the flyleaf and the covers.- "A First Review"

Goodbye to All That (1929)

- Graves' autobiography is famous for its vivid account of life in the trenches in the First World War (1914–18).

- James Burford, collier and fitter, was the oldest soldier of all. When I first spoke to him in the trenches, he said: "Excuse me, sir, will you explain what this here arrangement is on the side of my rifle?" "That's the safety catch. Didn't you do a musketry-course at the depôt?" "No, sir, I was a re-enlisted man, and I spent only a fortnight there. The old Lee-Metford didn't have no safety-catch." I asked him when he had last fired a rifle. "In Egypt in 1882," he said. "Weren't you in the South African War?" "I tried to re-enlist, but they told me I was too old, sir... My real age is sixty-three."

- Ch.12

- I protested: "But all this is childish. Is there a war on here, or isn't there?"

"The Royal Welch don't recognize it socially," he answered.- Ch.14

- Cuinchy bred rats. They came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses, and multiplied exceedingly. While I stayed here with the Welsh, a new officer joined the company... When he turned in that night, he heard a scuffling, shone his torch on the bed, and found two rats on his blanket tussling for the possession of a severed hand.

- Ch.14

- Having now been in the trenches for five months, I had passed my prime. For the first three weeks, an officer was of little use in the front line... Between three weeks and four weeks he was at his best, unless he happened to have any particular bad shock or sequence of shocks. Then his usefulness gradually declined as neurasthenia developed. At six months he was still more or less all right; but by nine or ten months, unless he had been given a few weeks' rest on a technical course, or in hospital, he usually became a drag on the other company officers. After a year or fifteen months he was often worse than useless.

- On being in the trenches in France in 1915, Ch.16

- There was a daily exchange of courtesies between our machine guns and the Germans' at stand-to; by removing cartridges from the ammunition-belt one could rap out the rhythm of the familiar prostitutes' call: "MEET me DOWN in PICC-a-DILL-y", to which the Germans would reply, though in slower tempo, because our guns were faster than theirs: "YES, with-OUT my DRAWERS ON!"

- Ch.16

- Patriotism, in the trenches, was too remote a sentiment, and at once rejected as fit only for civilians, or prisoners. A new arrival who talked patriotism would soon be told to cut it out.

- Ch. 17

- Hardly one soldier in a hundred was inspired by religious feeling of even the crudest kind. It would have been difficult to remain religious in the trenches even if one had survived the irreligion of the training battalion at home.

- Ch. 17

- Anglican chaplains were remarkably out of touch with their troops. The Second Battalion chaplain, just before the Loos fighting, had preached a violent sermon on the Battle against Sin, at which one old soldier behind me had grumbled: "Christ, as if one bloody push wasn't enough to worry about at a time!"

- Ch. 17

- England looked strange to us returned soldiers. We could not understand the war madness that ran about everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet. The civilians talked a foreign language; and it was newspaper language.

- Ch. 21

- "I got shot in the guts at the Beaumont-Hamel show. It hurt like hell, let me tell you. They took me down to the field-hospital. I was busy dying, but a company-sergeant major had got it in the head, and he was busy dying, too; and he did die. Well, as soon as ever the sergeant-major died, they took out that long gut... and they put it into me, grafted it on somehow. Wonderful chaps, these medicos! … Well, this sergeant-major seems to have been an abstemious man. The lining of the new gut is much better than my old one; so I'm celebrating it. I only wish I'd borrowed his kidneys, too."

- Ch.21

- Opposite our trenches a German salient protruded, and the brigadier wanted to "bite it off" in proof of the division's offensive spirit. Trench soldiers could never understand the Staff's desire to bite off an enemy salient. It was hardly desirable to be fired at from both flanks; if the Germans had got caught in a salient, our obvious duty was to keep them there as long as they could be persuaded to stay. We concluded that a passion for straight lines, for which headquarters were well known, had dictated this plan, which had no strategic or tactical excuse.

- Ch.22

- Nancy and I were married in January 1918 at St. James's Church, Piccadilly, she being just eighteen, and I twenty-two. George Mallory acted as the best man. Nancy had read the marriage-service for the first time that morning, and been so disgusted that she all but refused to go through with the wedding, though I had arranged for the ceremony to be modified and reduced to the shortest possible form. Another caricature scene to look back on: myself striding up the red carpet, wearing field-boots, spurs and sword; Nancy meeting me in a blue-check silk wedding-dress, utterly furious; packed benches on either side of the church, full of relatives; aunts using handkerchiefs; the choir boys out of tune; Nancy savagely muttering the responses, myself shouting them in a parade-ground voice.

- Ch. 25

- Shells used to come bursting on my bed at midnight, even though Nancy shared it with me; strangers in daytime would assume the faces of friends who had been killed... I could not use a telephone, I felt sick every time I travelled by train, and to see more than two new people in a single day prevented me from sleeping.

- Ch.26 On being at home in Harlech in 1919. During the First World War, the mental effects of war on the fighting men were called shell shock or neurasthenia — or dismissed altogether as cowardice. Graves describes very clearly symptoms of what would now be seen as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- In the middle of a lecture I would have a sudden very clear experience of men on the march up the Béthune–La Bassée road; the men would be singing... These daydreams persisted like an alternate life and did not leave me until well in 1928. The scenes were nearly always recollections of my first four months in France; the emotion-recording apparatus seems to have failed after Loos.

- On studying at Oxford University in 1919, Ch. 27

- At the end of my first term's work, I attended the usual college board to give an account of myself. The spokesman coughed, and said a little stiffly: "I understand, Mr. Graves, that the essays which you write for your English tutor are, shall I say, a trifle temperamental. It appears, indeed, that you prefer some authors to others."

- Ch. 27

- Professor Edgeworth, of All Souls', avoided conversational English, persistently using words and phrases that one expects to meet only in books. One evening, Lawrence returned from a visit to London, and Edgeworth met him at the gate. "Was it very caliginous in the metropolis?"

"Somewhat caliginous, but not altogether inspissated," Lawrence replied gravely.

- Ch. 28

I, Claudius (1934)

- I, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus … this, that and the other (for I shall not trouble you yet with all my titles), who was once, and not so long ago either, known to my friends and relatives and associates as ‘Claudius the Idiot’, or ‘That Claudius’, or ‘Claudius the Stammerer’, or ‘Clau-Clau-Claudius’, or at best as ‘Poor Uncle Claudius’, am now about to write this strange history of my life; starting from my earliest childhood and continuing year by year until I reach the fateful point of change where, some eight years ago, at the age of fifty-one, I suddenly found myself caught in what I may call the ‘golden predicament’ from which I have never since become disentangled.

- Ch. 1

- My tutor I have already mentioned, Marcus Porcius Cato who was, in his own estimation at least, a living embodiment of that ancient Roman virtue which his ancestors had one after the other shown. He was always boasting of his ancestors, as stupid people do who are aware that they have done nothing themselves to boast about. He boasted particularly of Cato the Censor, who of all characters in Roman history is to me perhaps the most hateful, as having persistently championed the cause of "ancient virtue" and made it identical in the popular mind with churlishness, pedantry and harshness.

- Ch. 5

- Athenodorus used to stroke his beard slowly and rhythmically as he talked, and told me once that it was this that made it grow so luxuriantly. He said that invisible seeds of fire streamed off from his fingers, which were food for the hairs. This was a typical Stoic joke at the expense of Epicurean speculative philosophy.

- Ch. 5

- Postumus was clever: he guessed that this would make Cato angry enough to forget himself. And Cato rose to the bait, shouting out with a string of old-fashioned curses that in the days of his ancestor, whose memory this stammering imp was insulting, woe betide any child who failed in reverence to his elders; for they dealt out discipline with a heavy hand in those days. Whereas in these degenerate times the leading men of Rome gave any ignorant oafish lout (this was for Postumus) or any feeble-minded decrepit-limbed little whippersnapper (this was for me) full permission—

Postumus interrupted with a warning smile: "So I was right. The degenerate Augustus insults the great Censor by employing you in his degenerate family. I suppose you have told the Lady Livia just how you feel about things?"- Ch. 5

- Caligula then reintroduced treason as a capital crime, ordered his speech to be at once engraved on a bronze tablet and posted on the wall of the House [where the Senate assembled for legislative and administrative work] above the seats of the Consuls, and rushed away. No more business was transacted that day; we were all too dejected. But the next day we lavished praise on Caligula as a sincere and pious ruler and voted annual sacrifices to his Clemency. What else could we do? He had the army at his back, and power of life or death over us, and until someone was bold and clever enough to make a successful conspiracy against his life all that we could do was to humor him and hope for the best.

- Ch. 31

Claudius the God (1935)

Jove sent them Old King Log.

- Nobody is familiar with his own profile, and it comes as a shock, when one sees it in a portrait, that one really looks like that to people standing beside one. For one's full face, because of the familiarity that mirrors give it, a certain toleration and even affection is felt; but I must say that when I first saw the model of the gold piece that the mint-masters were striking for me I grew angry and asked whether it was intended to be a caricature. My little head with its worried face perched on my long neck, and the Adam's apple standing out almost like a second chin, shocked me. But Messalina said: "No, my dear, that's really what you look like. In fact, it is rather flattering than otherwise."

- Ch. 6

- The frog-pool wanted a king.

Jove sent them Old King Log.

I have been as deaf and blind and wooden as a log.

The frog-pool wanted a king.

Let Jove now send them Young King Stork.

Caligula's chief fault: his stork-reign was too brief.

My chief fault: I have been far too benevolent.

I repaired the ruin my predecessors spread.

I reconciled Rome and the world to monarchy again.

Rome is fated to bow to another Caesar.

Let him be mad, bloody, capricious, wasteful, lustful.

King Stork shall prove again the nature of kings.

By dulling the blade of tyranny I fell into great error.

By whetting the same blade I might redeem that error.

Violent disorders call for violent remedies.

Yet I am, I must remember, Old King Log.

I shall float inertly in the stagnant pool.

Let all the poisons that lurk in the mud hatch out.- Ch. 30

The Reader Over Your Shoulder (1943)

- This "Handbook for Writers of English Prose" was written in collaboration with Alan Hodge

- Where is good English to be found? Not among those who might be expected to write well professionally. Schoolmasters seldom write well: it is difficult for any teacher to avoid either pomposity or, in the effort not to be pompous, a jocular conversational looseness. The clergy suffer from much the same occupational disability: they can seldom decide whether to use "the language of the market-place" or Biblical rhetoric. Men of letters usually feel impelled to cultivate an individual style — less because they feel sure of themselves as individuals than because they wish to carve a niche for themselves in literature; and nowadays an individual style usually means merely a peculiar range of inaccuracies, ambiguities, logical weaknesses and stylistic extravagancies. Trained journalists use a flat, over-simplified style, based on a study of what sells a paper and what does not, which is inadequate for most literary purposes.

- Ch. 3: "Where Is Good English to Be Found?"

- Faults in English prose derive not so much from lack of knowledge, intelligence or art as from lack of thought, patience or goodwill.

- Ch. 3: "Where Is Good English to Be Found?"

- The official style is at once humble, polite, curt and disagreeable: it derives partly from that used in Byzantine times by the eunuch slave-secretariat, writing stiffly in the name of His Sacred Majesty, whose confidence they enjoyed, to their fellow-slaves outside the palace precincts — for the Emperor had summary power over everyone; and partly from the style used by the cleric-bureaucracy of the Middle Ages, writing stiffly in the name of the feudal lords to their serfs and, though cautious of offending their employers, protected from injury by being servants of the Church, not of the Crown, and so subject to canon, not feudal, law. The official style of civil servants, so far as it recalls its Byzantine derivation, is written by slaves to fellow-slaves of a fictitious tyrant; and, so far as it recalls its mediaeval derivation, is written by members of a quasi-ecclesiastical body, on behalf of quasi-feudal ministers (who, being politicians, come under a different code of behaviour from theirs) to a serflike public.

- Ch. 4: "The Use and Abuse of Official English"

- The chief trouble with the official style is that it spreads far beyond the formal contexts to which it is suited. Most civil servants, having learned to write in this way, cannot throw off the habit. The obscurity of their public announcements largely accounts for the disrepute into which Departmental activities have fallen: for the public naturally supposes that Departments are as muddled and stodgy as their announcements.

The habit of obscurity is partly caused by a settled disinclination among public servants to give a definite refusal even where assent is out of the question; or to convey a vigorous rebuke even where, in private correspondence, any person with self-respect would feel bound to do so. The mood is conveyed by a polite and emasculated style — polite because, when writing to a member of the public, the public servant is, in theory at least, addressing one of his collective employers; emasculated because, as a cog in the Government machine, he must make his phrases look as mechanical as possible by stripping them of all personal feeling and opinion.- Ch.4: "The Use and Abuse of Official English"

King Jesus (1946)

- Jehovah, it seems clear, was once regarded as a devoted son the the Great Goddess, who obeyed her in all things and by her favor swallowed up a number of variously named rival gods and godlings — the Terebinth-god, the Thunder-god, the Pomegranate-god, the Bull-god, the Goat-god, the Antelope-god, the Calf-god, the Porpoise-god, the Ram-god, the Ass-god, the Barley-god, the god of Healing, the Moon-god, the god of the Dog-star, the Sun-god. Later (if it is permitted to write in this style) he did exactly what his Roman counterpart, Capitoline Jove, has done: he formed a supernal Trinity in conjunction with two of the Goddess's three persons, namely, Anatha of the Lions and Ashima of the Doves, the counterparts of Juno and Minerva; the remaining person, a sort of Hecate named Sheol, retiring to rule the infernal regions.

- By Jesus’s time the Law of Moses, originally established for the government of a semi-barbarous nation of herdsmen and hill-farmers, resembled a petulant great-grandfather who tries to govern a family business from his sick-bed in the chimney-corner, unaware of the changes that have taken place in the world since he was able to get about: his authority must not be questioned, yet his orders, since no longer relevant, must be reinterpreted in another sense, if the business is not to go bankrupt. When the old man says, for instance: “It is time for the women to grind their lapfuls of millet in the querns,” this is taken to mean: “It is time to send the sacks of wheat to the water-mill.”

- Ch. 21

The Greek Myths (1955)

- Ancient Europe had no gods. The Great Goddess was regarded as immortal, changeless, and omnipotent; and the concept of fatherhood had not been introduced into religious thought. She took lovers, but for pleasure, not to provide her children with a father. Men feared, adored, and obeyed the matriarch; the hearth which she tended in a cave or hut being their earliest social centre, and motherhood their prime mystery.

- Volume 1, Introduction

- When I say a man looks like a poet, I mean he looks like Robert Graves. Tall, angular, the lips sullen-sensual, the crushed but still diagrammatically aquiline nose, the rheumy eyes and their thousand-mile stare — and, with all this, a loose-limbed physicality, large, gestural: I remember him scaling the rocks that leaned up from the sandless shore — and bounding over them as he came back the other way and leapt flailing into the water. Here indeed was the warrior-poet.

- Martin Amis, Experience: A Memoir (2000)

- Graves has a very considerable brain, but his mixture is too rich. He's mad as a hatter, but brilliant.

- Cecil Day-Lewis, quoted in Andrew Duncan, The Reality of Monarchy

- Robert Graves stands impressively, cantankerously, comically, nobly apart from his contemporaries. You can't even classify him as the leader of his own school. He hasn't one. Indeed, it may be said that he draws his greatest strength from wrestling single-handed with the brutish mob.

- Christopher Isherwood, editor, Great English Short Stories (1957) [Laurel TM 674623], introduction to Graves' "The Shout"

- Graves is such a professional surpriser that only a conventional opinion from him could still shock us. It has been a unique privilege of our time to watch the building of Graves, from shell-shocked schoolboy in World War I to Mediterranean warlock, encanting at the Moon. As an expatriate in Majorca, Graves remains a bit of an Edwardian tease, as willful and unflaggingly facetious as a Sitwell; yet in another sense, he has grown more fully and richly than is given to most. His literary opinions are so quirky that they seem designed solely to start lengthy feuds in the London Times; yet in terms of his own art they are not quirky at all.

- Wilfrid Sheed, Introduction, The Paris Review, "Writers at Work: 4th series" (1969)

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.