Loading AI tools

Sir Martin Louis Amis (25 August 1949 – 19 May 2023) was a British novelist, essayist and short story writer. He was the son of Kingsley Amis.

- Style is not neutral; it gives moral directions.

- Novelists in Interview (1985) edited by John Haffenden

- Money doesn’t mind if we say it’s evil, it goes from strength to strength. It’s a fiction, an addiction, and a tacit conspiracy.

- Novelists in Interview (1985) edited by John Haffenden

- Every writer hopes or boldly assumes that his life is in some sense exemplary, that the particular will turn out to be universal.

- The Observer [London] (30 August 1987)

- Being inoffensive, and being offended, are now the twin addictions of the culture.

- "First Lady on Trial" The Sunday Times [London] (17 March 1996) (Online text in PDF format)

- It's been said that happiness writes white. It doesn't show up on the page. When you're on holiday and writing a letter home to a friend, no one wants a letter that says the food is good and the weather is charming and the accommodations comfortable. You want to hear about lost passports and rat-filled shacks.

- When you review an exhibition of paintings you don't compose a painting about it, when you review a film you don't make a film about it and when you review a new CD you don't make a little CD about it. But when you review a prose-narrative then you write a prose-narrative about that prose-narrative and those who write the secondary prose-narrative, let's face it, must have once had dreams of writing the primary prose-narrative. And so there is a kind of hierarchy of envy and all those other things.

- What happened on September 11? On September 11 — what happened? Picture this: two upended matchboxes, knocked over by the sheer force of paper-darts.

Only it was much, much worse than that. In fact, words alone cannot adduce how much worse it was than that. September 11 was an attack on words: we felt a general deficit. And with words destroyed, we had to make do, we had to bolster truth with colons and repetition: not only repetition: but repetition and: colons. This is what we adduce.

- America has had much more respect for its writers because they had to define what America was. America wasn't sure what it was.

- [I am] secular to the bones, but not an atheist.

- Quoted in Philip Ottermann, "Beyond belief," The Guardian (5 July 2008)

The Moronic Inferno and Other Visits to America (1986)

- One of the many things I do not understand about Americans is this: what is it like to be a citizen of a superpower, to maintain democratically the means of planetary extinction. I wonder how this contributes to the dreamlife of America, a dreamlife that is so deep and troubled.

- "Introduction"

- The true manipulator never has a reputation for manipulating.

- "Claus von Bülow" (1983)

- What is this televisual mastery of Reagan's? It is a celebration of good intentions and unexceptional abilities. His style is one of hammy self-effacement, a wry dismay at his own limited talents and their drastic elevation.

- "Ronald Reagan" (1979)

- In my experience of fights and fighting, it is invariably the aggressor who keeps getting everything wrong.

- "Gore Vidal" (1977)

- Our vulgar delight in American vulgarity.

- "The New Evangelists" (1980)

- When success happens to an English writer, he acquires a new typewriter. When success happens to an American writer, he acquires a new life.

- "Kurt Vonnegut" (1983)

- Probably all writers are at some point briefly under the impression that they are in the forefront of disintegration and chaos, that they are among the first to live and work after things fall apart. The continuity such an impression ignores is a literary continuity.

- "Joan Didion" (1980)

- The doltish euphemism of conglomerate America.

- "Hugh Hefner" (1985)

- Nowadays every business in America says how warm it is and how much it cares — loan companies, supermarkets, hamburger chains.

- "Hugh Hefner" (1985)

- In the end one cannot avoid the conclusion that AIDS unites certain human themes — homosexuality, sexual disease, and death — about which society actively resists enlightenment. These are things that we are unwilling to address or even think about. We don't want to understand them. We would rather fear them.

- "Making Sense of AIDS" (1985)

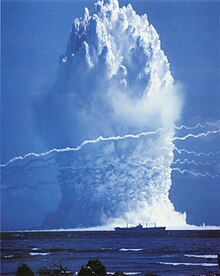

Einstein's Monsters (1987)

- Bullets cannot be recalled. They cannot be uninvented. But they can be taken out of the gun.

- "Introduction: Thinkability"

- What is the only provocation that could bring about the use of nuclear weapons? Nuclear weapons. What is the priority target for nuclear weapons? Nuclear weapons. What is the only established defense against nuclear weapons? Nuclear weapons. How do we prevent the use of nuclear weapons? By threatening to use nuclear weapons. And we can't get rid of nuclear weapons, because of nuclear weapons. The intransigence, it seems, is a function of the weapons themselves.

- "Introduction: Thinkability"

- For myself and my loved ones, I want the heat, which comes at the speed of light. I don’t want to have to hang about for the blast, which idles along at the speed of sound.

- "Introduction: Thinkability"

- The arms race is a race between nuclear weapons and ourselves.

- "Introduction: Thinkability"

- "Einstein's Monsters," by the way, refers to nuclear weapons, but also to ourselves. We are Einstein's monsters, not fully human, not for now.

- "Introduction: Thinkability"

- Bujak spoke of Einstein as if he were God's literary critic, God being a poet. I, more stolidly, tend to suspect that God is a novelist — a garrulous and deeply unwholesome one too.

- "Bujak and the Strong Force"

London Fields (1989)

- I know what his poetry will be about. What poetry is always about. The cruelty of the poet's mistress.

- She was sitting there beside the bookcase, trying to read, in a growing panic of self-consciousness. Why? Because reading presupposed a future.

- Someone watches over us when we write. Mother. Teacher. Shakespeare. God.

Visiting Mrs. Nabokov and Other Excursions (1993)

- It used to be said that by a certain age a man had the face that he deserved. Nowadays, he has the face he can afford.

- "Phantom of the Opera: The Republicans in 1988" (1988)

- Never content just to be, America is also obliged to mean; America signifies, hence its constant and riveting vulnerability to illusion.

- "Phantom of the Opera: The Republicans in 1988" (1988)

- Not greatly gifted, not deeply beautiful, Madonna tells America that fame comes from wanting it badly enough. And everyone is terribly good at badly wanting things.

- "Madonna" (1992)

"Political Correctness: Robert Bly and Philip Larkin" (1997)

- Laughter always forgives.

- What we eventually run up against are the forces of humourlessness, and let me assure you that the humourless as a bunch don't just not know what's funny, they don't know what's serious. They have no common sense, either, and shouldn't be trusted with anything.

- What is the deep background on the deep male? From 100,000 BC until, let's say, 1792 — Mary Wollstonecraft and her Vindication of the Rights of Women — there was simply the man, whose main characteristics was that he got away with everything. From 1792 until about 1970, there was, in theory anyway, the "enlightened" man, who, while continuing to get away with everything, agreed to meet women to talk about talks which would lead to political concessions. Post-1970, the enlightened man became the new man, who isn't interested in getting away with anything, who believes, indeed, that the female is not merely equal to the male but is his plain superior.

- Iron John, a short work of psychological, literary and anthropological speculation by the poet Robert Bly, dominated the New York Times best-seller list for nearly a year and made, as we shall see, a significant impact on many aspects of American life. In England, it made no impression whatever. ... We are British over in Britain, we are skeptical, ironical, et cetera, and are not given, as Americans are, to seeking expert advice on basic matters. Especially such matters as our manhood. In England, maleness itself has become an embarrassment: male consciousness, male pride, male rage, we don't want to hear about.

- Bly is a poet, he is a big cat, so to speak, and not some chipmunk from the how-to culture. But it is the how-to culture that has picked up on his book. ... And yet, for a while Iron John transformed male consciousness in the United States. The wild men weekends and initiation, adventure holidays and whatnot, which were big business, may prove to be ephemeral. But what does one make of the unabashed references in the press to "men's liberation" and the men's movement and the fact that there are now at least half a dozen magazines devoted to nothing else? Changing men, journeymen, man. … Bly's average reader is not a poet and a critic, but a weightlifter from Brooklyn.

- Feminists have often claimed a moral equivalence for sexual and racial prejudice. There are certain affinities and one or two of these affinities are mildly and paradoxically encouraging. Sexism is like racism: we all feel such impulses. Our parents feel them more strongly than we feel them; our children, we trust, will feel them less strongly than we feel them. People don't change or improve much, but they do evolve. It is very slow.

- Philip Larkin, a big, fat, bald librarian at the University of Hull, was unquestionably England's unofficial laureate: our best-loved poet since the war; better loved for our poet than John Betjeman, who was loved also for his charm, his famous beagle, his patrician Bohemianism and his televisual charisma, all of which Larkin notably lacked.

Ten years later, Larkin is now something like a pariah, or an untouchable.

- The reaction against Larkin has been unprecedentedly violent as well as unprecedentedly hypocritical, tendentious and smug. Its energy does not, could not derive from literature — it derives from ideology, or from the vaguer promptings of a new ethos. … This is critical revisionism in an eye-catching new outfit. The reaction, like most reactions, is just an overreaction, and to get an overreaction you need plenty of overreactors — somebody has to do it. ... I remember thinking when I saw the fiery Tom Paulin's opening shot, We're not really going to do this, are we? But the new ethos was already in place, and yes, we really were going to do this — on Paulin's terms, too. His language set the tone for the final assault and mop-up, which came with the publication of Andrew Motion's, Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life. Revolting. Sewer. Such language is essentially unstable. It calls for a contest of the passions and hopes that the fight will get dirty.

- They can't ban or burn Larkin's books. What they can embark on is the more genteel process of literary demotion.

- Exploitative is the key word here. It suggests that while you are free to be as sexually miserable as you like, the moment you exchange hard cash for a copy of Playboy, you are in the pornography perpetuation business, and your misery becomes political.

The truth is that pornography is just a sad affair all around. It is there because men in their hundreds of millions want it to be there. Killing pornography is like killing the messenger. The extent to which Larkin was "dependent" on pornography should be a measure our pity, or even our sympathy. But Motion hears the beep of his political pager, and he stands to attention.

- One wonders how the literary revisionists and canon cleansers can bear to take the money. Imagine a school of sixteenth century art criticism that spent its time contently jeering at the past for not knowing about perspective.

- Just as a Philistine does not on the whole devote his life to his art, so a misogynist does not devote his inner life to women. Larkin's men friends devolved into pen-pals. Such intimacies as he shared, he shared with women.

- Words are not deeds. In published poems — we think first of Eliot's "Jew", words edge closer to deeds. In Céline's anti-Semitic textbooks, words get as close to deeds as words can well get. Blood libels scrawled on front doors are deed.

In a correspondence, words are hardly even words. They are soundless cries and whispers, "gouts of bile," as Larkin characterized his political opinions, ways of saying, "Gloomy old sod, aren't I?" Or more simply, "Grrr."

Correspondences are self-dramatizations. Above all, a word in a letter is never your last word on any subject. There was no public side to Larkin's prejudices, and nothing that could be construed as a racist — the word suggest a system of thought, rather than an absence of thought, which would be closer to the reality, closer to the jolts and twitches of self response.

- Viewed at its grandest, P.C. is an attempt to accelerate evolution. To speak truthfully, while that's still okay, everybody is a racist or has racial prejudices. This is because human beings tend to like the similar, the familiar, the familial. Again, I say, I am a racist. I am not as racist as my parents. My children will not be as racist as I am. Freedom from racial prejudice is what we hope for down the line. Impatient with this hope, this process, P.C. seeks to get things done right now. In a generation or at the snap of a finger, you can simply announce yourself to be purged of these atavisms.

- In Andrew Motion's book, we have the constant sense that Larkin is somehow falling short of the cloudless emotional health enjoyed by, for instance, Andrew Motion. Also the sense, as Motion invokes his like-minded contemporaries, that Larkin is being judged by a newer, cleaner, braver, saner world. … Motion is extremely irritated by Larkin's extreme irritability. He's always complaining that Larkin is always complaining.

- His last words were spoken to a woman, to the nurse who was holding his hand. Perhaps we all have the last words ready when we go into the last room. Perhaps the thing about last words is not how good they are, but whether we can get them out. What Larkin said faintly was, "I'm going to the inevitable."

- A life is one kind of biography and the letters are another kind of life, but the internal story, the true story is in the Collected Poems. The recent attempts by Motion and others to pass judgement on Larkin look awfully green and pale, compared with the self-examinations of the poetry. They think they judge him? No, he judges them. His indivisibility judges their hedging and trimming. His honesty judges their watchfulness.

- Larkin the man is separated from us historically by changes in the self. For his generation, you were what you were and that was that. It made you unswervable and adamantine. My father had this quality. I don't. None of us do. There are too many forces at work, there are too many fronts to cover.

Still, a price has to be paid for not caring what others think of you, and Larkin paid it. He couldn't change the cards he was dealt. What poor hands we hold, when we face each other honestly. His poems insist on this helplessness...

- Is there any good reason why we cannot extend our multi-cultural generosity to include another dimension? That of time. The past, too, is another country. Its ghosts may look strange and frightening and slightly misshapen in body and mind, but all the more reason then, to welcome them to our shores.

Question and answer session:

- I think it's the whole impulse to judge and censor and euphemize, that is the enemy. … What fun, to feel superior to T. S. Eliot. And that's the impulse that I am suspicious of.

- I think enlightenment is incremental, and I see it in my children. I was six-years-old when I met a black person. My father tutored me and said, "We're going to meet two men who have black skin." And on the bus in Swansea on the way there, I accepted this and thought this would be no trouble for me. As it was, I went into the room and burst into tears and pointed at the man and said, "You've got a black face."

This wouldn't happen with my children. They've known, they've mingled with black people all their lives. This certainly is not going to occur. And so it goes on in this incremental way. … I think this is the only way it can be achieved. The trouble with proclaiming yourself to be cleansed of atavism is that it's not the case. It's an illusion. It's an illusion that can only be maintained by ideology and executive policing. It is forced consciousness. It's a lie to say, I have no racial feelings. Honesty and slow progress is a better policy, I think.

Experience (2000)

- The trouble with life (the novelist will feel) is its amorphousness, its ridiculous fluidity. Look at it: thinly plotted, largely themeless, sentimental and ineluctably trite. The dialogue is poor, or at least violently uneven. The twists are either predictable or sensationalist. And it's always the same beginning; and the same ending ...

- Introduction

- By calling him humourless I mean to impugn his seriousness, categorically: such a man must rig up his probity ex nihilo.

- Part I: Failures of Tolerance

- All publicity isn't good publicity. As a New York publicist put it: "What: the guy's an asshole so I'll go and buy his novel?"

- Part I: Thinking with the Blood

- Kingsley fell over. And this was no brisk trip or tumble. It was an act of colossal administration. First came a kind of slow-leak effect, giving me the immediate worry that Kingsley, when fully deflated, would spread out into the street on both sides of the island, where there were cars, trucks, sneezing buses. Next, as I grabbed and tugged, he felt like a great ship settling on its side: would it right itself, or go under? Then came an impression of overall dissolution and the loss of basic physical coherence. I groped around him, looking for places to shore him up, but every bit of him was falling, dropping, seeking the lowest level, like a mudslide.

- Part II: One Little More Hug

The War Against Cliché: Essays and Reviews 1971-2000 (2001)

- Literary criticism, now almost entirely confined to the universities, thus moves against talent by moving against the canon. Academic preferment will not come from a respectful study of Wordsworth's poetics; it will come from a challenging study of his politics — his attitude to the poor, say, or his unconscious 'valorization' of Napoleon; and it will come still faster if you ignore Wordsworth and elevate some (justly) neglected contemporary, by which process the canon may be quietly and steadily sapped.

- Foreword, p. xii

- One of the historical vulnerabilities of literature, as a subject for study, is that it has never seemed difficult enough. This may come as news to the buckled figure of the book reviewer, but it's true. Hence the various attempts to elevate it, complicate it, systematize it. Interacting with literature is easy.

- Foreword, p. xiii

- Does screen violence provide a window or a mirror? Is it an effect or a cause, an encouragement, a facilitation? Fairly representatively, I think, I happen to like screen violence while steadily execrating its real-life counterpart. Moreover, I can tell the difference between the two. One is happening, one is not.

- Review of Hollywood vs. America by Michael Medved, p. 16

- Like Bradley Pearson in The Black Prince, 'N', as he is called, uses quotation marks for such vulgarisms as 'sulks,' 'commuters' and 'worthwhile activities', as well as for phrases like 'too good to be true', 'the wrong end of the stick' and 'keep in touch.' The reader reflects that a cliché or approximation, wedged between two inverted commas, is still a cliché or approximation. Besides, you see how it would 'get on your nerves' if I were to 'go on' like this 'the whole time'...

- Review of The Philosopher's Pupil by Iris Murdoch, p. 92

- Like all obsessions, Ballard's novel is occasionally boring and frequently ridiculous. The invariance of its intensity is not something the reviewer can easily suggest. Ballard is quite unlike anyone else; indeed, he seems to address a different - a disused - part of the reader's brain. You finish the book with some bafflement and irritation. But this is only half the experience. You then sit around waiting for the novel to come and haunt you. And it does.

- Review of The Day of Creation by J. G. Ballard, p. 109

- Not many people know this, but on top of writing regularly for every known newspaper and magazine, Anthony Burgess writes regularly for every unknown one, too. Pick up a Hungarian quarterly or a Portuguese tabloid - and there is Burgess, discoursing on goulash or test-driving the new Fiat 500. 'Wedged as we are between two eternities of idleness, there is no excuse for being idle now.' Even today, at seventy, and still producing book after book, Burgess spends half his time writing music. He additionally claims to do all the housework.

- Opening paragraph of his review of Little Wilson and Big God: Being the First Part of the Confessions of Anthony Burgess, p. 123

- It would be inaccurate to say that John Fowles is a middlebrow writer who sometimes hopes he is a highbrow: it has never occurred to him to believe otherwise. There is a difference, morally.

- Opening lines of his review of Mantissa by John Fowles, p. 138

- 'Beautifully written . . . the webs of imagery that Harris has so carefully woven . . . contains writing of which our best writers would be proud . . . there is not a singly ugly or dead sentence . . .' - or so sang the critics. Hannibal is a genre novel, and all genre novels contain dead sentences - unless you feel the throb of life in such periods as 'Tommaso put the lid back on the cooler' or 'Eric Pickford answered' or 'Pazzi worked like a man possessed' or 'Margot laughed in spite of herself' or 'Bob Sneed broke the silence.' What these commentators must be thinking of, I suppose, are the bits when Harris goes all blubbery and portentous (every other phrase a spare tyre), or when, with a fugitive poeticism, he swoons us to a dying fall: 'Starling looked for a moment through the wall, past the wall, out to forever and composed herself...' 'It seemed forever ago...' 'He looked deep, deep into her eyes...' 'His dark eyes held her whole...' Needless to say, Harris has become a serial murderer of English sentences, and Hannibal is a necropolis of prose.

- Review of Hannibal by Thomas Harris, p. 240

- No one in the history of the written word, not even William MacGonagall, or Spike Milligan or D. H. Lawrence, is so wide open to damaging quotation. Try this, more or less at random: 'A murderer in the moment of his murder could feel a sense of beauty and perfection as complete as the transport of a saint.' Or this: Film is a phenomenon whose resemblance to death has been ignored for too long. His italics.

On every page Mailer will come up with a formulation both grandiose and crass. This is expected of him. It is also expected of the reviewer to introduce a lingering 'yet' or 'however' at some point, and say that 'somehow' Mailer's 'fearless honesty' redeems his notorious excesses. He isn't frightened of sounding outrageous; he isn't frightened of making a fool of himself; and, above all, he isn't frightened of being boring. Well, fear has its uses. Perhaps he ought to be a little less frightened of being frightened.- Review of The Essential Mailer by Norman Mailer, p. 267

- As it turns out, Mailer comes close to solving the mystery [of Lee Harvey Oswald], but he never establishes the tragedy. Dreiser's tale was tragic and American because it happened every day. Oswald made only one notch in the calendar. It was meaningless; he just renamed an airport, violently.

...Oswald's life was not a cry of pain so much as a squawk for attention. He achieved geopolitical significance by the shortest possible route. He was not an example of post-modern absurdity but one of its messiahs: an inspiration to the glazed loner. He killed Kennedy not to impress Jodie Foster. He killed Kennedy to impress Clio - the muse of history.- Review of Oswald's Tale: An American Mystery by Norman Mailer, p. 277

- Vidal is determined to be a) in the thick of things, and b) above the fray. He knows everybody and he doesn't want to know anybody. He has had lovers by the thousand while doing 'nothing' — deliberately, at least — to please the other.

- Review of Palimpsest by Gore Vidal, p. 279

- As elsewhere in his writing, Vidal gives the impression of believing that the entire heterosexual edifice - registry offices, Romeo and Juliet, the disposable diaper - is just a sorry story of self-hypnosis and mass hysteria: a hoax, a racket, or sheer propaganda.

- Review of Palimpsest, p. 281

- It isn't that the beau monde was too big for Capote's talents. The beau monde was too small for Capote's talents. Here, at least, in human terms the Very Rich are very poor. Interestingly, they are not interesting; incredibly, they are not even credible. They are certainly not the 'unspoiled monsters' of Capote's chapter title: they are spoiled mediocrities, they are boring freaks. The backgammon bums, the sweating champagne buckets, 'the Racquet Club, Le Jockey, the Links, White's', 'Lafayette, The Colony, La Grenouille, La Caravelle', 'Vuitton cases, Battistoni shirts, Lanvin suits, Peal shoes': how keen can a writer afford to be on all this?

- Review of "Answered Prayers" by Truman Capote, p. 311

- Of obvious appeal to the humourless is the writer who comes on stage in a clown outfit or King Kong suit, with party hat and harem slippers, with banana skins and custard pies... It remains a sound rule that funny journalism can only flourish as the offshoot or sideline of something larger. No funny journalist who is that and nothing more will ever write anything lastingly funny.

- Review of The Best of Modern Humour edited by Mordecai Richler, p. 364

- While clearly an impregnable masterpiece, Don Quixote suffers from one fairly serious flaw - that of outright unreadability. This reviewer should know, because he has just read it. The book bristles with beauties, charm, sublime comedy; it is also, for long stretches (approaching about 75 per cent of the whole), inhumanly dull.... Reading Don Quixote can be compared to an indefinite visit from your most impossible senior relative, with all his pranks, dirty habits, unstoppable reminiscences, and terrible cronies. When the experience is over, and the old boy checks out at last (on page 846 - the prose wedged tight, with no breaks for dialogue), you will shed tears all right: not tears of relief but tears of pride. You made it, despite all that Don Quixote could do.

- Opening paragraph of his review of The Adventures of Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes, translated by Tobias Smollett

- It occurs to you that Ulysses is about cliché. It is about inherited, ready-made formulations - most notably Irish Catholicism and anti-Semitism. After all, prejudices are clichés: they are secondhand hatreds . . . Joyce never uses a cliché in innocence.

- Review of Ulysses by James Joyce, p. 444

- Tell a dream, lose a reader, said Henry James. Joyce told a dream, Finnegans Wake, and he told it in puns - cornily but rightly regarded as the lowest form of wit. This showed fantastic courage, and fantastic introversion. The truth is Joyce didn't love the reader, as you need to do. Well, he gave us Ulysses, incontestably the central modernist masterpiece; it is impossible to conceive of any future novel that might give the form such a violent evolutionary lurch. You can't help wondering, though. Joyce could have been the most popular boy in school, the funniest, the cleverest, the kindest. He ended with a more ambiguous distinction: he became the teacher's pet.

- Review of Ulysses, p. 446

"Fear and loathing" (2001)

- It was the advent of the second plane, sharking in low over the Statue of Liberty: that was the defining moment. Until then, America thought she was witnessing nothing more serious than the worst aviation disaster in history; now she had a sense of the fantastic vehemence ranged against her.

- For those thousands in the south tower, the second plane meant the end of everything. For us, its glint was the worldflash of a coming future.

Terrorism is political communication by other means. The message of September 11 ran as follows: America, it is time you learned how implacably you are hated. United Airlines Flight 175 was an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile aimed at her innocence. That innocence, it was here being claimed, was a luxurious and anachronistic delusion.

- A week after the attack, one is free to taste the bile of its atrocious ingenuity. It is already trite — but stringently necessary — to emphasise that such a mise en scène would have embarrassed a studio executive's storyboard or a thriller-writer's notebook ("What happened today was not credible," were the wooden words of Tom Clancy, the author of The Sum of All Fears). And yet in broad daylight and full consciousness that outline became established reality: a score or so of Stanley knives produced two million tons of rubble.

- This moment was the apotheosis of the postmodern era — the era of images and perceptions. Wind conditions were also favourable; within hours, Manhattan looked as though it had taken 10 megatons.

- The bringers of Tuesday's terror were morally "barbaric", inexpiably so, but they brought a demented sophistication to their work. They took these great American artefacts and pestled them together. Nor is it at all helpful to describe the attacks as "cowardly". Terror always has its roots in hysteria and psychotic insecurity; still, we should know our enemy. The firefighters were not afraid to die for an idea. But the suicide killers belong in a different psychic category, and their battle effectiveness has, on our side, no equivalent. Clearly, they have contempt for life. Equally clearly, they have contempt for death.

Their aim was to torture tens of thousands, and to terrify hundreds of millions. In this, they have succeeded.

- Weirdly, the world suddenly feels bipolar. All over again the west confronts an irrationalist, agonistic, theocratic/ideocratic system which is essentially and unappeasably opposed to its existence. The old enemy was a superpower; the new enemy isn't even a state. In the end, the USSR was broken by its own contradictions and abnormalities, forced to realise, in Martin Malia's words, that "there is no such thing as socialism, and the Soviet Union built it". Then, too, socialism was a modernist, indeed a futurist, experiment, whereas militant fundamentalism is convulsed in a late-medieval phase of its evolution. We would have to sit through a renaissance and a reformation, and then await an enlightenment. And we're not going to do that.

- Violence must come; America must have catharsis. We would hope that the response will be, above all, non-escalatory. It should also mirror the original attack in that it should have the capacity to astonish. A utopian example: the crippled and benighted people of Afghanistan, hunkering down for a winter of famine, should not be bombarded with cruise missiles; they should be bombarded with consignments of food, firmly marked LENDLEASE — USA.

- Our best destiny, as planetary cohabitants, is the development of what has been called "species consciousness" — something over and above nationalisms, blocs, religions, ethnicities. During this week of incredulous misery, I have been trying to apply such a consciousness, and such a sensibility. Thinking of the victims, the perpetrators, and the near future, I felt species grief, then species shame, then species fear.

"The voice of the lonely crowd" (2002)

- On any longer view, man is only fitfully committed to the rational — to thinking, seeing, learning, knowing. Believing is what he's really proud of.

- September 11 was a day of de-Enlightenment. Politics stood revealed as a veritable Walpurgis Night of the irrational. And such old, old stuff. The conflicts we now face or fear involve opposed geographical arenas, but also opposed centuries or even millennia. It is a landscape of ferocious anachronisms: nuclear jihad in the Indian subcontinent; the medieval agonism of Islam; the Bronze Age blunderings of the Middle East.

- The 20th century, with its scores of millions of supernumerary dead, has been called the age of ideology. And the age of ideology, clearly, was a mere hiatus in the age of religion, which shows no sign of expiry. Since it is no longer permissible to disparage any single faith or creed, let us start disparaging all of them. To be clear: an ideology is a belief system with an inadequate basis in reality; a religion is a belief system with no basis in reality whatever. Religious belief is without reason and without dignity, and its record is near-universally dreadful. It is straightforward — and never mind, for now, about plagues and famines: if God existed, and if He cared for humankind, He would never have given us religion.

- My apostasy, at the age of nine, was vehement. Clearly, I didn't want the shared words, the shared identity. I forswore chapel; those Bibles were scribbled on and otherwise desecrated, and two or three of them were taken into the back garden and quietly torched.

Later — we were now in Cambridge — I gave a school speech in which I rejected all belief as an affront to common sense. I was an atheist, and I was 12: it seemed open-and-shut. I had not pondered Kant's rather lenient remark about the crooked timber of humanity, out of which nothing straight is ever built. Nor was I aware that the soul had legitimate needs.

Much more recently I reclassified myself as an agnostic. Atheism, it turns out, is not quite rational either. The sketchiest acquaintance with cosmology will tell you that the universe is not, or is not yet, decipherable by human beings. It will also tell you that the universe is far more bizarre, prodigious and chillingly grand than any doctrine, and that spiritual needs can be met by its contemplation. Belief is otiose; reality is sufficiently awesome as it stands.

- PC is low, low church — it is the lowest common denomination.

- The champions of militant Islam are, of course, misogynists, woman-haters; they are also misologists — haters of reason. Their armed doctrine is little more than a chaotic penal code underscored by impotent dreams of genocide. And, like all religions, it is a massive agglutination of stock response, of cliches, of inherited and unexamined formulations.

- After September 11, then, writers faced quantitative change, but not qualitative change. In the following days and weeks, the voices coming from their rooms were very quiet; still, they were individual voices, and playfully rational, all espousing the ideology of no ideology. They stood in eternal opposition to the voice of the lonely crowd, which, with its yearning for both power and effacement, is the most desolate sound you will ever hear. "Desolate": "giving an impression of bleak and dismal emptiness... from L. desolat-, desolare 'abandon', from de- 'thoroughly' + solus 'alone'."

"The Palace of the End" (2003)

- We accept that there are legitimate casus belli: acts or situations "provoking or justifying war". The present debate feels off-centre, and faintly unreal, because the US and the UK are going to war for a new set of reasons (partly undisclosed) while continuing to adduce the old set of reasons (which in this case do not cohere or even overlap).

- Like all "acts of terrorism" (easily and unsubjectively defined as organised violence against civilians), September 11 was an attack on morality: we felt a general deficit. Who, on September 10, was expecting by Christmastime to be reading unscandalised editorials in the Herald Tribune about the pros and cons of using torture on captured "enemy combatants"? Who expected Britain to renounce the doctrine of nuclear no-first-use? Terrorism undermines morality. Then, too, it undermines reason. … No, you wouldn't expect such a massive world-historical jolt, which will reverberate for centuries, to be effortlessly absorbed. But the suspicion remains that America is not behaving rationally — that America is behaving like someone still in shock.

- The notion of the "axis of evil" has an interesting provenance. In early drafts of the President's speech the "axis of evil" was the "axis of hatred", "axis" having been settled on for its associations with the enemy in the second world war. The "axis of hatred" at this point consisted of only two countries, Iran and Iraq. whereas of course the original axis consisted of three (Germany, Italy, Japan). It was additionally noticed that Iran and Iraq, while not both Arab, were both Muslim. So they brought in North Korea.

We may notice, in this embarras of the inapposite, that the Axis was an alliance, whereas Iran and Iraq are blood-bespattered enemies, and the zombie nation of North Korea is, in truth, so mortally ashamed of itself that it can hardly bear to show its face.

- It was explained that the North Korean matter was a diplomatic inconvenience, while Iraq's non-disarmament remained a "crisis". The reason was strategic: even without WMDs, North Korea could inflict a million casualties on its southern neighbour and raze Seoul. Iraq couldn't manage anything on this scale, so you could attack it. North Korea could, so you couldn't. The imponderables of the proliferation age were becoming ponderable. Once a nation has done the risky and nauseous work of acquisition, it becomes unattackable. A single untested nuclear weapon may be a liability. But five or six constitute a deterrent.

From this it crucially follows that we are going to war with Iraq because it doesn't have weapons of mass destruction. Or not many. The surest way by far of finding out what Iraq has is to attack it. Then at last we will have Saddam's full cooperation in our weapons inspection, because everything we know about him suggests that he will use them all. The Pentagon must be more or less convinced that Saddam's WMDs are under a certain critical number. Otherwise it couldn't attack him.

- All US presidents — and all US presidential candidates — have to be religious or have to pretend to be religious. More specifically, they have to subscribe to "born again" Christianity. Bush, with his semi-compulsory prayer-breakfasts and so on, isn't pretending to be religious... We hear about the successful "Texanisation" of the Republican party. And doesn't Texas sometimes seem to resemble a country like Saudi Arabia, with its great heat, its oil wealth, its brimming houses of worship, and its weekly executions?

- Saddam's hands-on years in the dungeons distinguish him from the other great dictators of the 20th century, none of whom had much taste for "the wet stuff". The mores of his regime have been shaped by this taste for the wet stuff — by a fascinated negative intimacy with the human body, and a connoisseurship of human pain.

- There are two rules of war that have not yet been invalidated by the new world order. The first rule is that the belligerent nation must be fairly sure that its actions will make things better; the second rule is that the belligerent nation must be more or less certain that its actions won't make things worse. America could perhaps claim to be satisfying the first rule (while admitting that the improvement may be only local and short term). It cannot begin to satisfy the second.

"Off the Page: Martin Amis" (2003)

- I once wrote, in The Information, that an Englishman wouldn't bother to attend a reading even if the author in question was his favorite living writer, and also his long-lost brother — even if the reading was taking place next door. Whereas Americans go out and do things. But Meeting the Author, for me, is Meeting the Reader. Some of the little exchanges that take place over the signing table I find very fortifying: they make up for some of the other stuff you get.

- I'd like to be remembered as someone who kept the comic novel going for another generation or so. I fear the comic novel is in retreat. A joke is by definition politically incorrect — it assumes a butt, and a certain superiority in the teller. The culture won't put up with that for much longer.

- I have been outflanked by the culture. I am now seen as a drawling Oxonian, and a genetic elitist, who took over the family firm. People subconsciously think that I was born in 1922, wrote Lucky Jim when I was 7, and will live for at least a century. This feels odd to me, because my father was a "angry young man" and helped democratize the British novel. I'm not a toff. I'm a yob.

Playboy interview (2003)

- I'm not sure what the American convulsion at the moment is, but I get the impression that people have moved beyond political correctness there by now. But here it lingers, although much ridiculed.

- It now seems that pornography is the leading sex educator in the Western world. And the idea of having your sexual nature determined by a medallion-in-the-chest-hair artist out in Los Angeles is really humiliating. I'm not talking about me, but I'm talking about my children's contemporaries, kids aged 18. They're getting their sex tips from some charlatan at Wicked Video.

- I think it's a very confused culture. On the one hand, no one is better than anyone else; no one is prettier. On the other hand, everyone is completely obsessed by their looks and by how they strike the world. On the one hand, we're all equal; on the other hand, everyone's a superstar. It's all very irrational, like all ideology.

- If people have personal conversations about very emotional matters in public, and people reveal parts of their body that were originally kept covered, and pornography is becoming semi-respectable, it makes you think the push for greater freedom and divesting yourself of inhibitions is a real human need. I'm 54, so I'm further back upon the road. We certainly did a fair amount of divesting ourselves of inhibitions, but there seems to have been a quantum leap in the last half a generation. Maybe we're destined to be freer, but it's taking odd forms, like showing your big gut to all the world and discussing the future of your marriage at a bus stop with 30 people listening in.

- Sex has become much more competitive, with the girls becoming sort of predators as well. It's ferocious.

The Pregnant Widow (2010)

- Envy is negative empathy.

- "Second Interval"

- It kept astonishing him — how weak the prohibitions always turned to be, and how ready everyone was to claim the new ground, every inch of it. An automatic annexation. What was called, in children, self-extension, as they stockpiled each dawning power and freedom, without gratitude, without thought. And now: where were the hinderers, the wet blankets, where were the miseries, where were the police?

- Book Three "The Incredible Shrinking Man" 3: "Martyr"

- You know, it's not the rich who're really different from us. It's the beautiful.

- Book Five "Trauma" 1: "The Turn"

- In the seventeenth century, it is said, there was a dissociation of sensibility. The poets could no longer think and feel at the same time.[…] All we are saying is that something analogous happened while the children of the Golden Age were becoming men and women. Feeling was already separated from thought. And then feeling was separated from sex.

- "Fifth Interval"

- It was already obvious that every hard and demanding adaptation would be falling to the girls. Not to the boys — who were all like that anyway. The boys could just go on being boys. It was the girls who had to choose.

- Book Six "The Problem of Re-entry" 3: "The Pool Hut"

- She went at it as if the sexual act, in all human history, had never even been suspected of leading to childbirth, as if everyone had immemorially known that it was by other means that you peopled the world. All the ancient colourations of significance and consequence had been bleached from it... Whenever he thought of her naked body (and this would go on being true), he saw something like a desert, he saw a beautiful Sahara, with its slopes and dunes and whorls, its shadows and sandy vapours and tricks of the light, its oases, its mirages.

- Book Six "The Problem of Re-entry" 4: "When They Hate You Already". (Ellipsis in original)

- Pornographic sex is a kind of sex that can be described. Which told you something, he felt, about pornography, and about sex. During Keith's time, sex divorced itself from feeling. Pornography was the industrialization of that rift.

- "2009 — Valedictory"

- She thought of an article she had once seen on mind control. Apparently if there was a person fiendish enough to set about interfering with your life, the only thing you could do was to concentrate hard on someone they were unlikely ever to have heard of called Martin Amis. The particular blankness of this image was guaranteed to protect from any subtle force, but Gloria realised with a sinking heart that it was too late now.

- Martin Amis's reputation as the bad boy of British writing shouldn't overpower the fact that he's simply a fantastic writer. His brash, intelligent novels are sharp with insight, and his wordplay makes reading Amis feel like playing: swinging high in a swing, hanging from monkey bars, just having fun.

Yet his view of the world is not a light one... authors across the "pond" often hone a super-realism that is actually bleak. Amis's hyperbole makes his works funny, but they're funny with an edge.

- Martin, rather than step into the spotlight, would prefer to die in an unarmed attack on the power station supplying its electric current. His genuine modesty is the main reason for the fateful discrepancy between him and the journalistic literary sexton beetles who make copy out of him: they would like to receive the degree of attention that he would like to avoid, and the clearer it becomes that he would like to avoid it, the more they resent him for failing to appreciate their generosity.

- Clive James, North Face of Soho

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.