Loading AI tools

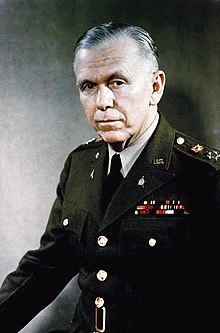

General George Catlett Marshall (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, then served as Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense under Truman. Winston Churchill lauded Marshall as the "organizer of victory" for his leadership of the Allied victory in World War II. As Secretary of State, Marshall advocated a U.S. economic and political commitment to post-war European recovery, including the Marshall Plan that bore his name. In recognition of this work, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953, the only United States Army general to receive this honor.

- I would say—when the fighting is at its fiercest, it is invariably the Infantry that carries the ball over for the touchdown.

- Quoted from Katherine Tupper Marshall, Annals, p. 153

- You know, I know, all of us know that the time factor is the vital consideration — and vital is the correct meaning of the term — of our national defense program; that we must never be caught in the same situation we found ourselves in 1917.

- Speech to the Army ordinance Association (11 October 1939); The Papers of George Catlett Marshall Vol 2 (1986) by the George C. Marshall Foundation, Ch. 2 "The Time Factor"

- I cannot afford the luxury of sentiment, mine must be cold logic.

- Quoted from George Marshall: Defender of the Republic

- The time has come when we must proceed with the business of carrying the war to the enemy, not permitting the greater portion of our armed forces and our valuable material to be immobilized within the continental United States.

- As quoted by the Times-Herald [Washington, D.C.] (3 March 1942) p. 1

- Not one American soldier is going to die on that goddamned beach.

- reaction to Churchill's pitch at the Cairo Conference in November 1943 for the Americans to join in an assault on Rhodes. quoted by Correl, John T. “Churchill’s Southern Strategy.” Air Force Magazine, January 2013

- We are determined that before the sun sets on this terrible struggle, Our Flag will be recognized throughout the World as a symbol of Freedom on the one hand and of overwhelming force on the other.

- Statement (29 May 1942); The Papers of George Catlett Marshall Vol 3 (1991) by the George C. Marshall Foundation

- The one great element in continuing the success of an offensive is maintaining the momentum. This was lost last fall when shortages caused by the limitation of port facilities made it impossible to get sufficient supplies to the armies when they approached the German border.

- Speech to the Overseas Press Club (1 March 1945)

- If man does find the solution for world peace it will be the most revolutionary reversal of his record we have ever known.

- Biennial Report of the Chief of Staff, US Army (1 September 1945)

- The refusal of the British and Russian peoples to accept what appeared to be inevitable defeat was the great factor in the salvage of our civilization.

- Biennial Report of the Chief of Staff, US Army (1 September 1945)

- I said bluntly that if the president were to follow Mr. Clifford's advice and if in the elections I were to vote, I would vote against the president.

- Statement indicating his opposition to Clark Clifford's advice to Harry S Truman for the US recognition of the state of Israel prior to UN decisions on the partitioning of Palestine, in official State Department records. (12 May 1948)

- If you follow Clifford's advice and if I were to vote in the election, I would vote against you.

- Marshall's statement as quoted by Clark Clifford in The New Yorker (25 March 1991)

- It is not enough to fight. It is the spirit which we bring to the fight that decides the issue. It is morale that wins the victory.

- Military Review (October 1948)

- Morale is the state of mind. It is steadfastness and courage and hope. It is confidence and zeal and loyalty. It is élan, esprit de corps and determination.

- Military Review (October 1948)

- The only way human beings can win a war is to prevent it.

- Various sources below attribute this statement or similar ones to Marshall

- But a war to prevent a third world war would be the Third World War, and Marshall had reached the conclusion that, "The only way human beings can win a war is to prevent it."

- As quoted in This is Our World (1956) by Louis Fisher, p. 91

- Marshall's motto read: "The only way human beings can win a war is to prevent it." It was 1947.

- Frances Perkins recalled his saying, "The only way human beings can win a war is to prevent it."

- “Its purpose is to avoid war, not to provoke it,” he explained to his goddaughter, Rose Page Wilson. The deterrence factor was vital. “The only way to be sure of winning a third world war is to prevent it,” Marshall warned.

- Unsourced variant: The only way to win a war is to prevent it.

- A very similar statement appears in the US Strategic Bombing Survey Summary Report (European War) (30 September 1945), p. 41:

- The great lesson to be learned in the battered towns of England and the ruined cities of Germany is that the best way to win a war is to prevent it from occurring.

- The hardest thing I ever did was keep my temper at that time.

- A comment to a personal friend, about Joseph McCarthy's attacks upon his loyalty (which went so far as to call him a "traitor"), as quoted by Alistair Cooke, in Letter from America : General Marshall (16 October 1959), published in Memories of the Great and the Good (1999)

- I was very careful to send Mr. Roosevelt every few days a statement of our casualties. I tried to keep before him all the time the casualty results because you get hardened to these things and you have to be very careful to keep them always in the forefront of your mind.

- As quoted by Forrest C. Pogue, in "George C. Marshall: Global Commander" (1968)

- Don’t fight the problem, decide it.

- As quoted in The Wise Men (1986) by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas

- Variant: Don't fight the problem. Decide it!

- As quoted in General of the Army : George C. Marshall, Soldier and Statesman (1991) by Ed Cray, p. 591

- I don't want you fellows sitting around asking me what to do. I want you to tell me what to do.

- To his staffers, as quoted in General of the Army : George C. Marshall, Soldier and Statesman (1991) by Ed Cray, p. 591

- Military power wins battles, but spiritual power wins wars.

- As quoted in A Toolbox for Humanity: More Than 9000 Years of Thought (2004) by Lloyd Albert Johnson

- When a thing is done, it's done. Don't look back. Look forward to your next objective.

The Marshall Plan Speech (1947)

- Speech at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts introducing what became known as the Marshall Plan (5 June 1947) · "The Marshall Plan Speech" information page at the George C. Marshal Foundation · Audio recording with slide presentation of images of post-war Europe

- I need not tell you that the world situation is very serious. That must be apparent to all intelligent people. I think one difficulty is that the problem is one of such enormous complexity that the very mass of facts presented to the public by press and radio make it exceedingly difficult for the man in the street to reach a clear appraisement of the situation. Furthermore, the people of this country are distant from the troubled areas of the earth and it is hard for them to comprehend the plight and consequent reactions of the long-suffering peoples, and the effect of those reactions on their governments in connection with our efforts to promote peace in the world.

- For the past ten years conditions have been abnormal. The feverish preparation for war and the more feverish maintenance of the war effort engulfed all aspects of national economies. Machinery has fallen into disrepair or is entirely obsolete. Under the arbitrary and destructive Nazi rule, virtually every possible enterprise was geared into the German war machine. Long-standing commercial ties, private institutions, banks, insurance companies, and shipping companies disappeared through loss of capital, absorption through nationalization, or by simple destruction. In many countries, confidence in the local currency has been severely shaken. The breakdown of the business structure of Europe during the war was complete.

- There is a phase of this matter which is both interesting and serious. The farmer has always produced the foodstuffs to exchange with the city dweller for the other necessities of life. This division of labor is the basis of modern civilization. At the present time it is threatened with breakdown. The town and city industries are not producing adequate goods to exchange with the food-producing farmer. Raw materials and fuel are in short supply. Machinery is lacking or worn out. The farmer or the peasant cannot find the goods for sale which he desires to purchase. So the sale of his farm produce for money which he cannot use seems to him an unprofitable transaction. He, therefore, has withdrawn many fields from crop cultivation and is using them for grazing. He feeds more grain to stock and finds for himself and his family an ample supply of food, however short he may be on clothing and the other ordinary gadgets of civilization. Meanwhile, people in the cities are short of food and fuel, and in some places approaching the starvation levels. So the governments are forced to use their foreign money and credits to procure these necessities abroad. This process exhausts funds which are urgently needed for reconstruction. Thus a very serious situation is rapidly developing which bodes no good for the world.

- The truth of the matter is that Europe's requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential products — principally from America — are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help or face economic, social, and political deterioration of a very grave character.

The remedy lies in breaking the vicious circle and restoring the confidence of the European people in the economic future of their own countries and of Europe as a whole. The manufacturer and the farmer throughout wide areas must be able and willing to exchange their product for currencies, the continuing value of which is not open to question.

- Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist. Such assistance, I am convinced, must not be on a piecemeal basis as various crises develop. Any assistance that this Government may render in the future should provide a cure rather than a mere palliative. Any government that is willing to assist in the task of recovery will find full cooperation, I am sure, on the part of the United States Government. Any government which maneuvers to block the recovery of other countries cannot expect help from us. Furthermore, governments, political parties or groups which seek to perpetuate human misery in order to profit therefrom politically or otherwise will encounter the opposition of the United States.

- An essential part of any successful action on the part of the United States is an understanding on the part of the people of America of the character of the problem and the remedies to be applied. Political passion and prejudice should have no part. With foresight, and a willingness on the part of our people to face up to the vast responsibility which history has clearly placed upon our country, the difficulties I have outlined can and will be overcome. ... to my mind, it is of vast importance that our people reach some general understanding of what the complications really are, rather than react from a passion or a prejudice or an emotion of the moment. As I said more formally a moment ago, we are remote from the scene of these troubles. It is virtually impossible at this distance merely by reading, or listening, or even seeing photographs or motion pictures, to grasp at all the real significance of the situation. And yet the whole world of the future hangs on a proper judgment.

Essentials to Peace (1953)

- Discussions without end have been devoted to the subject of peace, and the efforts to obtain a general and lasting peace have been frequent through many years of world history. There has been success temporarily, but all have broken down, and with the most tragic consequences since 1914. What I would like to do is point our attention to some directions in which efforts to attain peace seem promising of success.

- We have walked blindly, ignoring the lessons of the past, with, in our century, the tragic consequences of two world wars and the Korean struggle as a result.

In my country my military associates frequently tell me that we Americans have learned our lesson. I completely disagree with this contention and point to the rapid disintegration between 1945 and 1950 of our once vast power for maintaining the peace. As a direct consequence, in my opinion, there resulted the brutal invasion of South Korea, which for a time threatened the complete defeat of our hastily arranged forces in that field. I speak of this with deep feeling because in 1939 and again in the early fall of 1950 it suddenly became my duty, my responsibility, to rebuild our national military strength in the very face of the gravest emergencies.

- These opening remarks may lead you to assume that my suggestions for the advancement of world peace will rest largely on military strength. For the moment the maintenance of peace in the present hazardous world situation does depend in very large measure on military power, together with Allied cohesion. But the maintenance of large armies for an indefinite period is not a practical or a promising basis for policy. We must stand together strongly for these present years, that is, in this present situation; but we must, I repeat, we must find another solution, and that is what I wish to discuss this evening.

- There has been considerable comment over the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to a soldier. I am afraid this does not seem as remarkable to me as it quite evidently appears to others. I know a great deal of the horrors and tragedies of war. ... The cost of war in human lives is constantly spread before me, written neatly in many ledgers whose columns are gravestones. I am deeply moved to find some means or method of avoiding another calamity of war. Almost daily I hear from the wives, or mothers, or families of the fallen. The tragedy of the aftermath is almost constantly before me.

- A very strong military posture is vitally necessary today. How long it must continue I am not prepared to estimate, but I am sure that it is too narrow a basis on which to build a dependable, long-enduring peace. The guarantee for a long continued peace will depend on other factors in addition to a moderated military strength, and no less important. Perhaps the most important single factor will be a spiritual regeneration to develop goodwill, faith, and understanding among nations. Economic factors will undoubtedly play an important part. Agreements to secure a balance of power, however disagreeable they may seem, must likewise be considered. And with all these there must be wisdom and the will to act on that wisdom.

- Because wisdom in action in our Western democracies rests squarely upon public understanding, I have long believed that our schools have a key role to play. Peace could, I believe, be advanced through careful study of all the factors which have gone into the various incidents now historical that have marked the breakdown of peace in the past. As an initial procedure our schools, at least our colleges but preferably our senior high schools, as we call them, should have courses which not merely instruct our budding citizens in the historical sequence of events of the past, but which treat with almost scientific accuracy the circumstances which have marked the breakdown of peace and have led to the disruption of life and the horrors of war.

- I believe our students must first seek to understand the conditions, as far as possible without national prejudices, which have led to past tragedies and should strive to determine the great fundamentals which must govern a peaceful progression toward a constantly higher level of civilization. There are innumerable instructive lessons out of the past, but all too frequently their presentation is highly colored or distorted in the effort to present a favorable national point of view. In our school histories at home, certainly in years past, those written in the North present a strikingly different picture of our Civil War from those written in the South. In some portions it is hard to realize they are dealing with the same war. Such reactions are all too common in matters of peace and security. But we are told that we live in a highly scientific age. Now the progress of science depends on facts and not fancies or prejudice. Maybe in this age we can find a way of facing the facts and discounting the distorted records of the past.

- I am certain that a solution of the general problem of peace must rest on broad and basic understanding on the part of its peoples. Great single endeavors like a League of Nations, a United Nations, and undertakings of that character, are of great importance and in fact absolutely necessary, but they must be treated as steps toward the desired end.

- In America we have not suffered the destruction of our homes, our towns, and our cities. We have not been enslaved for long periods, at the complete mercy of a conqueror. We have enjoyed freedom in its fullest sense. In fact, we have come to think in terms of freedom and the dignity of the individual more or less as a matter of course, and our apparent unconcern until times of acute crisis presents a difficult problem to the citizens of the countries of Western Europe, who have seldom been free from foreign threat to their freedom, their dignity, and their security. I think nevertheless that the people of the United States have fully demonstrated their willingness to fight and die in the terrible struggle for the freedom we all prize...I recognize that there are bound to be misunderstandings under the conditions of wide separation between your countries and mine. But I believe the attitude of cooperation has been thoroughly proven.

- We must present democracy as a force holding within itself the seeds of unlimited progress by the human race. By our actions we should make it clear that such a democracy is a means to a better way of life, together with a better understanding among nations. Tyranny inevitably must retire before the tremendous moral strength of the gospel of freedom and self-respect for the individual, but we have to recognize that these democratic principles do not flourish on empty stomachs, and that people turn to false promises of dictators because they are hopeless and anything promises something better than the miserable existence that they endure. However, material assistance alone is not sufficient. The most important thing for the world today in my opinion is a spiritual regeneration which would reestablish a feeling of good faith among men generally. Discouraged people are in sore need of the inspiration of great principles. Such leadership can be the rallying point against intolerance, against distrust, against that fatal insecurity that leads to war. It is to be hoped that the democratic nations can provide the necessary leadership.

- The points I have just discussed are, of course, no more than a very few suggestions in behalf of the cause of peace. I realize that they hold nothing of glittering or early promise, but there can be no substitute for effort in many fields. There must be effort of the spirit — to be magnanimous, to act in friendship, to strive to help rather than to hinder. There must be effort of analysis to seek out the causes of war and the factors which favor peace, and to study their application to the difficult problems which will beset our international intercourse. There must be material effort — to initiate and sustain those great undertakings, whether military or economic, on which world equilibrium will depend.

If we proceed in this manner, there should develop a dynamic philosophy which knows no restrictions of time or space. In America we have a creed which comes to us from the deep roots of the past. It springs from the convictions of the men and women of many lands who founded the nation and made it great. We share that creed with many of the nations of the Old World and the New with whom we are joined in the cause of peace.

- A great proponent of much of what I have just been saying is Dr. Albert Schweitzer, the world humanitarian, who today receives the Nobel Peace Award for 1952. I feel it is a vast compliment to be associated with him in these awards this year. His life has been utterly different from mine, and we should all be happy that his example among the poor and benighted of the earth should have been recognized by the Peace Award of the Nobel Committee.

- I fear, in fact I am rather certain, that due to my inability to express myself with the power and penetration of the great Churchill, I have not made clear the points that assume such prominence and importance in my mind. However, I have done my best, and I hope I have sown some seeds which may bring forth good fruit.

- The price of peace is eternal vigilance.

- This has been attributed to Marshall, and he might have used the phrase, but earlier uses exist:

- There is an imperialism that deserves all honor and respect — an imperialism of service in the discharge of great duties. But with too many it is the sense of domination and aggrandisement, the glorification of power. The price of peace is eternal vigilance.

- Leonard H. Courtney as quoted in The Life Of Lord Courtney (I920) by G. P. Gooch

- Courtney's statement however is probably derived from an earlier statement with several variants:

The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.

The price of liberty is eternal vigilance.

Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.- These have often been attributed to Thomas Jefferson, but also Thomas Paine, Abraham Lincoln, and many others; Alfred Denning in The Road to Justice (1988) states that the phrase originated in a statement of Irish orator John Philpot Curran in 1790: "It is the common fate of the indolent to see their rights become a prey to the active. The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance."

- We must stop setting our sights by the light of each passing ship; instead we must set our course by the stars.

- Many attribute this quote to Marshall, however, General Omar Bradley is the correct author. Statement by Bradley (31 May 1948), quoted in An Inconvenient Truth : The Planetary Emergency Of Global Warming And What We Can Do About It (2006) by Al Gore.

- In Marshall's presence ambition folds its tent.

- Anonymous British official, as quoted in Letter from America : General Marshall (16 October 1959) by Alistair Cooke, published in his Memories of the Great and the Good (1999)

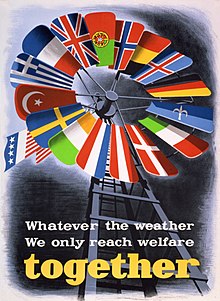

- The American economy had expanded greatly during the war, both in absolute and in relative terms. America had the manufacturing capacity, organisational capability, and fiscal resources to meet the costs of post-war military commitments. These strengths underpinned the American effort to resist the Communist advance. This effort was economic and political as well as military. In June 1947, the Americans offered Marshall Plan Aid, an economic aid policy to help recovery and to avoid a return to the beggar-my-neighbour devaluations of the 1930s. It was named after George Marshall, the Secretary of State from 1947 to 1949. The Marshall Plan committed the USA to European recovery, and recovery in terms of promoting a specific model of productivity as well as economies dominated by welfare states.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- The Marshall Plan enabled the economies of Western Europe to overcome their dollar shortage and thus to finance trade and investment. This ensured that American-style technologies could be adopted and also that free trade would benefit at the expense of protectionism. The greater integration of the Western economy was an important consequence, and the Marshall Plan led to the European Payments Union, which encouraged the ready convertibility of currency, and looked toward the establishment of the European Economic Community. Marshall Plan Aid was rejected by the Soviet Union as a form of economic imperialism. This aid certainly represented a demonstration of American strength that could serve to create links. This rejection created a new boundary line: between the areas that received such aid and those that did not.

- Jeremy Black, The Cold War: A Military History (2015)

- Ironically, during four years of war, MacArthur may have owed the most to the very people he was certain were out to discredit and disparage him. While never among his fans, Franklin Roosevelt and George Marshall nonetheless consistently supported MacArthur within the framework of their global priorities, from the first efforts to resupply the Philippines to MacArthur's appointment as Allied supreme commander. Even then, where would MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area have been had not Ernie King urged the Joint Chiefs to pour resources into the Pacific and wage a two-front war?

- Walter R. Borneman, MacArthur at War: World War II in the Pacific (2016), p. 507

- George Marshall may well have sighed at the results of the March 1945 poll- not at his own place but at MacArthur's. Marshall, more than most, knew the whole story of MacArthur's war. It is a mark of Marshall's own greatness that he so deftly managed MacArthur's fiery comet and unselfishly used its brilliance to accomplish the objectives of a global war.

- Walter R. Borneman, MacArthur at War: World War II in the Pacific (2016), p. 508

- King was unsympathetic with Marshall's dilemma in dealing with the imperious MacArthur, who had been a prewar Chief of Staff of the Army when Marshall still been a colonel. Marshall, he believed, "would do anything rather than disagree with MacArthur." (Nimitz was unquestioningly an obedient subordinate to King, but MacArthur's association with Marshall would be tenuous and tempestuous throughout the war.) King also suspected that Stimson uncritically supported MacArthur and pressured Marshall to appease the Southwest Pacific commander. This made King dislike Stimson even more. Marshall left his element and began foundering in uncharted waters when he argued that MacArthur should control fleet movements in his own area. His ignorance of naval communication procedures, for example, was glaringly exposed in a memorandum to King. "His basic trouble," King later said, "was that like all Army officers he knew nothing about sea power and very little about air power."

- Thomas B. Buell, Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King (1980), p. 216-217

- The squabble over who was to command what in the Pacific went on. King argued that speed was essential, further delay would allow the Japanese to recover from their Midway defeat and to resume their offensive in the Solomons. Reminding Marshall of their earlier agreement that the Army would exercise supreme command in Europe, King expected a quid pro quo in the Pacific. But with or without Army support, King intended to invade the Solomons. He instructed Nimitz to proceed with his invasion plans even though "there would probably be some delay in reaching a decision on the extent of the Army's participation." Marshall pondered King's ultimatum for three days. His mood worsened when he received an agitated dispatch from MacArthur, who was furious, almost paranoid, at King's presumptuousness in ordering Nimitz into MacArthur's area. The Navy, said MacArthur, was conspiring to reduce the Army in the Pacific to no more than an occupation force. Marshall finally suggested on 29 June that he and King talk about who would command the operation. (Incredibly, the two men up to this point had only exchanged memoranda.) King readily agreed. MacArthur's insistence that he command all operations in his area became irrelevant by the simple expedient of moving Nimit's western boundary line into MacArthur's territory. The result was that Nimitz's South Pacific Area was enlarged to include the eastern Solomons, including Tulagi. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley would command the eastern Solomons assault, identified as Task I. Subsequent assaults, referred to as Tasks II and III, would follow in the western Solomons, eastern New Guinea, and the Bismarck Archipelago. As these latter areas were still in MacArthur's domain, the General would be in command. After nearly a month of haggling, King and Marshall were finally able to agree on their Pacific strategy on 2 July. The eastern Solomons landings would begin in 1 August 1942. The American counteroffensive in the Pacific was almost underway.

- Thomas B. Buell, Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King (1980), p. 217

- General George Catlett Marshall is widely accepted as this nation's most esteemed 20th century military figure and as a paragon of professionalism and officership... His was a career that paralleled America's rise to and acceptance of global responsibilities. Marshall was a creator not only of America's awesome military power as Army chief of staff in World War II but also of its major foreign and global strategies as a postwar Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense. Statesman as well as soldier, his character and accomplishments are so exceptional that he is regularly placed in the company of George Washington when parallels are sought.

- Colonel Charles F. Brower in George C. Marshall: A Study in Character (1999)

- He is the true 'organizer of victory.'

- Winston Churchill in a telegram to Washington D.C. (1945)

- There are few men whose qualities of mind and character have impressed me so deeply as those of General Marshall. He is a great American but he is far more than that. In war he was as wise and understanding in counsel as he was resolute in action. In peace he was the architect who planned the restoration of our battered European economy and at the same time laboured tirelessly to establish a system of Western defense. He has always fought victoriously against defeatism, discouragement, and disillusion. Succeeding generations must not be allowed to forget his achievements and his example.

- Winston Churchill as quoted in The Age of Man: The Ascent Of Morality (2004) by Jim Bryan

- Hitherto I had thought of Marshall as a rugged soldier and a magnificent organizer and builder of armies — the American Carnot. But now I saw that he was a statesman with a penetrating and commanding view of the whole scene.

- Winston Churchill in The Second World War Vol. 4 (1950)

- I hope I won't be misunderstood if I say that he was a most un-American figure because he was so remarkably self-effacing. The United States has as many people as anybody afflicted with selfeffacement, but it usually springs from social discomfort or genuine shyness, for all that other form of shyness which, as somebody wisely said, is a sure sign of conceit. This man was not shy, but at the subordination of selfless teamwork was almost an instinct with him, and I suppose few men who take to soldiering took it for a better reason. Most Americans were willing to credit reports of his eminence but it was something they had to take on trust, for General George Catlett Marshall, of all the great figures of our time, was the least "colorful", the least impressive in a casual meeting and the least rewarding to the collector of anecdotes. He was a man whose inner strength and secret humour only slowly dripped through the surfaces of life, as a stalactite hangs stiff and granity for centuries before one sees beneath it a pool of still water of marvelous purity.

- Alistair Cooke, Letter from America : General Marshall (16 October 1959), published in Memories of the Great and the Good (1999)

- A high subordinate who worked with him assures me that in the history of warfare Marshall could not have had his equal as a master of supply: the first master, as this West Point colonel put it, of global warfare. … But to most of us, unifying the command of an army outpost or totting up the number of landing barges that could be spared from Malaya for the Normandy Landing is hardly still flashing as Montgomery's long dash through the desert, or MacArthur vigil on Bataan, or even the single syllable by which General McAuliffe earned his immortality: "Nuts!"

A layman is not going to break out a flag for a man who looks like the stolid golf-club secretary, a desk general who refused an aide-de-camp or a chauffeur and worked out of an office with six telephones. Even though 1984 comes closer every day, this is not yet an acceptable recipe for a hero. Though no doubt when Hollywood comes to embalm him on celluloid, he will grow a British basso, which is practically a compulsory grafting process for American historical characters in movies. He will open letters with a toy replica of the sword of Stonewall Jackson (who was, to be truthful, a lifetime's Idol).

But in life no such colour brightened the grey picture of a man devoted to the daily study of warfare on several continents with all the ardour of a certified public accountant. In a word, he was a soldier's soldier. Nor, I fear, is there any point in looking for some deep and guilty secret to explain his reputation for justice and chivalry.- Alistair Cooke, Letter from America : General Marshall (16 October 1959), published in Memories of the Great and the Good (1999)

- There is a final story about him which I happen to have from the only other man of three present. I think it will serve as a proper epitaph. In the early 1950s, a distinguished, avery lordly, American magazine publisher badgered Marshall to see him on what he described as a serious professional mission. He was invited to the general's summer home in Virginia. After a polite lunch, the general, the publisher, and the third man retired to the study. The publisher had come to ask the general to write his war memoirs. They would be serialized in the magazine and a national newspaper, and the settlement for the book publication will be a handsome indeed. The general instantly refused on the grounds that his own true opinion of several wartime decisions had differed from the president's. To advertise the difference now would leave Roosevelt's defense unspoken and would imply that many lives might have been saved. Moreover, any honest account might offend the living men involved and hurt the widow and family of the late president. The publisher pleaded for two hours."We have had, "he said, "the personal statements of Eisenhower, Bradley, Churchill, Stimson, James Byrnes. Montgomery is coming up, and Allanbrooke, and yet there is one yawning the gap." The General was adamant. At last, the publisher said, "General, I will tell you how essential we feel it is to have you fill that gap, weather with two hundred thousand words or ten thousand. I am prepared to offer you one million dollars after taxes for that manuscript. General Marshall was faintly embarrassed, but quite composed." But, sir," he said, "you don't seem to understand. I'm not interested in one million dollars."

- Alistair Cooke, Letter from America : General Marshall (16 October 1959), published in Memories of the Great and the Good (1999)

- I know that from your own viewpoint your magnificent accomplishments of the past six years have represented a mere performance of duty but I sincerely trust that you have some inkling of the extraordinary place your work has won for you in the respect and affections of the whole country. For myself I want only to assure you once again that in every problem and in every test I have faced during the war years, your example has been an inspiration and your support has been my greatest strength. My sense of obligation to you is equaled only by the depth of my pride and satisfaction as I salute you as the greatest soldier of our time and a true leader of democracy.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, in a ceremony at the Pentagon (26 November 1945), published in The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower: Occupation, 1945 (1970), edited by Alfred Dupont Chandler and Louis Galambos, p. 548

- I have been saying that ever since I first knew him well, that he, to me, has typified all that we call or that we look for in what we call an American patriot. I saw many things he did that were proof, to me, at least, of his selflessness. … I shall continue to say it until there is evidence — that I just don't believe exists in the world — that I am wrong. … I think it is a sorry reward, at the end of at least 50 years of service to this country, to say that he is not a loyal, fine American, and that he served only in order to advance his own personal ambitions. I can't imagine anyone that known in my career of whom this is less so than it is in his case.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, in a press conference (4 August 1954), as quoted in U.S. News & World Report, Vol. 3 (1954), also in Facts On File Yearbook Vol. 14 (1955), p. 261

- While Stalin was undertaking that risk, Marshall—following Truman’s lead—was constructing a Cold War grand strategy. Kennan’s “long telegram” had identified the problem: the Soviet Union’s internally driven hostility toward the outside world. It had, however, suggested no solution. Now Marshall told Kennan to come up with one: the only guideline was to “avoid trivia.” The instruction, it is fair to say, was met. The European Recovery Program, which Marshall announced in June, 1947, committed the United States to nothing less than the reconstruction of Europe. The Marshall Plan, as it instantly came to be known, did not at that point distinguish between those parts of the continent that were under Soviet control and those that were not—but the thinking that lay behind it certainly did.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (2005) p. 31

- Several premises shaped the Marshall Plan: that the gravest threat to western interests in Europe was not the prospect of Soviet military intervention, but rather the risk that hunger, poverty, and despair might cause Europeans to vote their own communists into office, who would then obediently serve Moscow’s wishes; that American economic assistance would produce immediate psychological benefits and later material ones that would reverse this trend; that the Soviet Union itself would not accept such aid or allow its satellites to, thereby straining its relationship with them; and that the United States could then seize both the geopolitical and the moral initiative in the emerging Cold War. Stalin fell into the trap the Marshall Plan laid for him, which was to get him to build the wall that would divide Europe.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (2005) p. 32

- While he was in Europe, Marshall traveled around and was appalled by what he saw- wrecked homes and buildings, people on the verge of starvation, recession, black markets, begging in the streets, and black despair. He began to realize that if something were not done t alleviate the situation Europe might fall into the abyss. By this time, following the death of Franklin Roosevelt, politically, the honeymoon was over for Harry S. Truman. Marshall knew that, in the present air of austerity, Congress was unlikely to make any large appropriation in the president's name to assist the situation in Europe. So on June 5, 1947, at the graduation ceremonies at Harvard where he was receiving an honorary degree, Marshall surprised the world by announcing the need for a European recovery program led by the United States. It was broad, expansive, and expensive. All European nations were invited to participate, including the Soviet Union and its new satellites, though Marshall added, "Any government that maneuvers to block the recovery of other countries cannot expect help from us." The Europeans that applied for help, he said, must come up with their own plan, and America would support the program "as far as it may be practical for us to do so." European reporters had been alerted to the speech and it caused a great stir in the press. One of Truman's advisors suggested to his boss it ought to be named the Truman Plan, but the president was politically savvy enough to know that would be difficult if not impossible to get past the Republicans in Congress. "Call it the Marshall Plan," Truman said.

- Winston Groom, The Generals: Patton, MacArthur, Marshall, and the Winning of World War II (2015), p. 437-438

- Marshall testified before the appropriations committee and, shortly afterward, the money was forthcoming. Americans had read of the destitution in Europe and were in the mood to help. In the end, seventeen countries participated to the tune of $17 billion for four years. The Marshall Plan was credited with speeding European recovery by perhaps a decade. The Soviet Union declined to participate and refused to let its satellite countries do so, dooming them to even more backwardness than the Communist economic system that held them down. Marshall for the second time became Times Man of the Year in 1947, and six year later he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work.

- Winston Groom, The Generals: Patton, MacArthur, Marshall, and the Winning of World War II (2015), p. 438

- For all their disagreements, King and Marshall had formed a good working partnership. Marshall did not ask for too much on MacArthur's behalf, and King refused to squeeze every drop of blood from the Army at the cost of his relationship with Marshall. The hard-swearing, hard-drinking womanizer from Ohio understood, better than most Army strategists, the symbiotic relationship among air, land, and sea forces. It would be a long war, and though they would lock horns from time to time, he and Marshall knew they would have to "get along" a while longer.

- David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (1999), p. 240-241

- George Marshall was in the habit of speaking bluntly to his superiors. As a young captain with the American Expeditionary Force in France in 1917, he had dared to correct General John J. Pershing in front of a group of fellow officers. Pershing responded by making Marshall his principal aide. But despite his anointing by the legendary Pershing, Marshall, in common with almost all officers of the postwar years, had languished in the missionless peacetime Army, where promotion was slow and action rare. He remained a lieutenant colonel for eleven years. He uncomplainingly accepted a series of apparently dead-end assignments: with the tiny U.S. Army garrison in Tientsin, China; with the Illinois National Guard; and even with the Civilian Conservation Corps. Yet everywhere he made a consistent impression as an outstanding soldier. His directness, his keen analytic mind, his unadorned speech, and his granitic constancy evoked admiration that bordered on reverence. More than one of his commanding officers, answering the routine efficiency report question of whether they would like to have Marshall serve under them in battle, replied that they would like to serve under his command- the highest of soldierly compliments. Marshall was just shy of six feet tall, ramrod-straight, invariably proper, impeccably controlled, and determinedly soft-spoken. Most associates saw only fleeting glimpses of his potentially volcanic temper.

- David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (1999), p. 430

- We were conscious of a great sense of excitement about the plan. Marshall himself was a great, great man — funny, odd but great — Olympian in his moral quality. We'd stay up all night, night after night. The first work ever done that I know about in economics on computers used the Pentagon's computers at night for the Marshall Plan. I had a tremendous sense of gratification from working so hard on it.

- Charles P. Kindleberger, on his involvement in development of the Marshall Plan, as quoted in "MIT Professor Kindleberger dies at 92", in MIT News (7 July 2003)

- The President and the Prime Minister had discussed the matter repeatedly, and both seemingly favored Marshall for the command. King felt that Marshall too wanted it, although he never said so. It was only natural, in King's view, that he should want it, as it was the most enviable duty that could come to any military man during the war. Nevertheless King felt strongly that Marshall was indispensable as a member of the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff, however desirable he might be as Supreme Commander. During the Quebec Conference when Secretary Knox, who had by exception been present for a couple of days, King had insisted forcibly that Marshall could not be spared, as he was a key-man, both in the United States and in the Allied organizations, and it seemed a poor idea to swap horses in midstream. Secretary Knox had countered that no one remembered the name of the Chief of Staff of the Army during World War I, whereas everyone knew General Pershing. King had pointed out, however, that World War II was very different from World War I, since now there were many oceans and many continents to be considered, against the single Atlantic Ocean and the single continent of Europe in the previous war.

- Ernest King and Walter M. Whitehill, commenting on consideration for Marshall to command Operation Overlord, in Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record (1952), p. 503

- Throughout the war, the four of us- Marshall, King, Arnold, and myself- worked in the closest possible harmony. In the postwar period, General Marshall and I disagreed sharply on some aspects of our foreign political policy. However, as a soldier, he was in my opinion one of the best, and his drive, courage, and imagination transformed America's citizen army into the most magnificent fighting force ever assembled. In number of men and logistical requirements, his army operations were by far the largest. This meant that more time of the Joint Chiefs were spent on his problems than on any others- and he invariably presented them with skill and clarity.

- William D. Leahy, I Was There (1950), p. 104

- Fleet Admiral William Daniel Leahy's death was announced by the US Navy. On July 22 at noon, his casket was moved into the Bethlehem Chapel of the Episcopal Cathedral in Washington, DC, and for the next twenty-four hours his body lay surrounded by a naval honor guard before being brought into the nave for the funeral. His eleven honorary pallbearers consisted of his old friend Bill Hassett and ten naval officers who included his few remaining living friends from the Annapolis class of 1897. After the service, a motor procession brought the admiral to his final resting place in Arlington Cemetery. A nineteen-gun salute was fired, and then Leahy was laid beside his wife, Louise, where she had awaited him for seventeen years. Neither Dwight Eisenhower, Harry Truman, nor George Marshall were in attendance. Newspapers marked his passing, but the articles were perfunctory and often mistaken. The New York Times noted how he had all but disappeared from the public mind, having lived as a "recluse" for the past for years. The Washington Post missed his importance entirely, writing, "Yet despite his inner position, his contribution to evolving defense concepts probably was not profound." When George Marshall died three months later, the reaction could not have been more different. President Eisenhower issued a public proclamation announcing Marshall's passing and extolling his greatness. He ordered that the national flag be flown at half-mast on all US government buildings, military facilities, and warships, both at home and abroad, and to be kept that way until after the funeral. both Truman and Eisenhower attended the funeral, and Truman described Marshall as "the greatest general since Robert E. Lee... the greatest administrator since Thomas Jefferson. He was the man of honor, the man of truth, the man of greatest ability. He was the greatest of the great in our time." The general's death was soon followed by a hagiographic biography, the foundation of Marshall scholarships, a Marshall library, Marshall public schools, Marshall awards- a whole industry to perpetuate his memory. To this day, historians claim, with scant evidence, that he determined US strategy in World War II.

- Philips Payson O'Brien, The Second Most Powerful Man in the World: The Life of Admiral William D. Leahy, Roosevelt's Chief of Staff (2019), p. 447-448

- George Marshall had continued to fade slowly through various health problems, but in early 1959 he suffered an incapacitating stroke in Pinehurst, North Carolina. It took until the spring for him to be safely transported to Walter Reed, where he declined from wheelchair to full-time bed rest to oxygen, catheter, and feeding tubes, in and out of consciousness. John Foster Dulles was also on the same floor, near the end of his life, and Ike brought the visiting Winston Churchill in for one final meeting with his faithful secretary of state. On the way out, they looked in on George Marshall, the man Churchill had honored at the coronation of his own queen. The general had not the slightest idea who either of them were. They both left somberly, Churchill wiping tears from his eyes. Marshall hung on until the fall and died quietly in the early evening of October 16, 1959. He had left explicit instructions forbidding a funeral at the National Cathedral or lying in state in the Capitol Rotunda. He wanted no eulogy, and his interment was to be private. He left a short guest list that included Bob Lovett "if it is convenient" and Beetle Smith "if he is in town," but not Ike, though he left it up to Katherine to invite more guests as she thought appropriate. On October 20, a brilliant autumn day, his coffin was brought to the Fort Myer chapel for a short service. Before the family entered, Harry Truman and his former military aide, along with Dwight Eisenhower with his own aide, settled into the same pew in icy silence. When the abbreviated Episcopal rites were over, a caisson took the coffin down the hill from the Arlington National Cemetery's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to a grave next to the ones Lily and her mother had been buried in decades earlier. Katherine would join them there in 1978. Fittingly, his legacy is preserved primarily at the George C. Marshall Research Library on the campus of the Virginia Military Institute.

- Robert L. O'Connell, Team America: Patton, MacArthur, Marshall, Eisenhower, and the World They Forged (2022). New York: HarperCollins Publishers, p. 478-479

- The quiet power of the man lay in his utter selflessness. It lay in the dignity that emerges from every photograph you've ever seen of him. It lay in his hard work and his immense personal sacrifice. It lay in his compassion, his wisdom. George Marshall practically defined those virtues. Yet he would have thought it odd if you had tried to congratulate him for these things. To him, those virtues were simply expected of a citizen of this country.

- Colin Powell, in George C. Marshall : Soldier of Peace (1997) by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and George C. Marshall Foundation, p. 25

- General George Marshall, Army Chief of Staff during World War II, wanted desperately to lead the D-Day invasion of Europe. Any general would want to lead the "Great Crusade." But that didn't happen. The assignment went to General Eisenhower, one of his protégés and junior to him. President Roosevelt, well aware of how badly Marshall wanted the mission, discussed it with him. At the end of the conversation, as Marshall was leaving, Roosevelt said gently, "Well, I didn't feel that I could sleep at ease if you were out of Washington." Marshall, that great man, knew his place was not to wade into the surf out of a landing craft in the Philippines or command the assault on the Normandy beaches, but to ensure that MacArthur and Eisenhower could.

- Colin Powell, It Worked For Me: In Life and Leadership (2012), p. 58-59

- I couldn't sleep nights, George, if you were out of Washington.

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt's explanation of why he passed over Marshall, in naming Dwight D. Eisenhower as the Supreme Allied Commander in charge of "Operation Overlord", the D-Day invasion which Marshall had largely planned; as reported by Henry Stimson (c. 1943)

- Unsourced variant: I feel I could not sleep at night with you out of the country.

- I have never seen a task of such magnitude performed by a man... I have seen a great many soldiers in my lifetime and you, Sir, are the finest soldier I have ever known.

- Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, as quoted at American Experience (PBS)

- Douglas MacArthur was the last great 19th century soldier, while George Marshall was the first great 20th century soldier.

- Mark A. Stoler, Board of Trustees of the Society for Military History

- General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, was F.D.R.'s ablest strategist.

- C.L. Sulzberger, in his book The American Heritage Picture History of World War II (1966), p. 312

- In a war unparalleled in magnitude and horror, millions of Americans gave their country outstanding service; General of The Army George C. Marshall gave it victory.

- Harry S. Truman, in an ceremony at the Pentagon, awarding Marshall an Oak Leaf Cluster to add to his Distinguished Service Cross (26 November 1945)

- In all my contacts with Marshall I found him as a rule coolly impersonal, with little humor. He could laugh, but he never gave evidence of a deep-seated pleasure in life. I know of many acts of kindness and thoughtfulness on his part, and I myself had reason to be grateful to him for having given me the opportunity to prove my worth as a planner, but he kept everyone at arm's length. It was typical of him that no one I knew, with the exception of General Stilwell, ever called him by his Christian name or was on terms of even the beginnings of familiarity with George Catlett Marshall.

- Albert C. Wedemeyer, Wedemeyer Reports! (1958), p. 122

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.