Loading AI tools

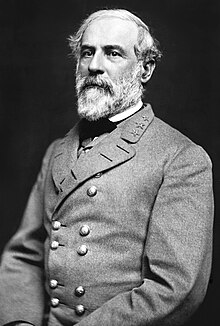

Robert Edward Lee (19 January 1807 – 12 October 1870) was an American soldier known for commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia (and eventually all the armies of the Confederacy as general-in-chief) in the American Civil War from 1862 until his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant in 1865. The son of Revolutionary War officer Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III, Lee was a top graduate of the United States Military Academy and an exceptional officer and military engineer in the United States Army for 32 years. During this time, he served throughout the United States, distinguished himself during the Mexican–American War, served as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy, and married Mary Custis.

- Madam, don't bring up your sons to detest the United States government. Recollect that we form one country now. Abandon all these local animosities, and make your sons Americans.

- Advice to a Confederate widow who expressed animosity towards the northern U.S. after the end of the American Civil War, as quoted in The Life and Campaigns of General Lee (1875) by Edward Lee Childe, p. 331. Also quoted in "Will Confederate Heritage Advocates Take Robert E. Lee’s Advice?" (July 2014), by Brooks D. Simpson, Crossroads, WordPress. This quote is sometimes paraphrased as: "Madam, do not train up your children in hostility to the government of the United States. Remember, we are all one country now. Dismiss from your mind all sectional feeling, and bring them up to be Americans."

- We must forgive our enemies. I can truly say that not a day has passed since the war began that I have not prayed for them.

- As quoted in A Life of General Robert E. Lee (1871), by John Esten Cooke

- I cannot consent to place in the control of others one who cannot control himself.

- Comment regarding officers who became inebriated, as quoted in Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (1874) by John William Jones, p. 170

- Sir, if you ever presume again to speak disrespectfully of General Grant in my presence, either you or I will sever his connection with this university.

- After one of the faculty at Washington College in Virginia (now Washington & Lee University) had spoken insultingly of Ulysses S. Grant, as quoted in Lee the American (1912) by Gamaliel Bradford, p. 226

- The forbearing use of power does not only form a touchstone, but the manner in which an individual enjoys certain advantages over others is a test of a true gentleman.

The power which the strong have over the weak, the employer over the employed, the educated over the unlettered, the experienced over the confiding, even the clever over the silly — the forbearing or inoffensive use of all this power or authority, or a total abstinence from it when the case admits it, will show the gentleman in a plain light.

The gentleman does not needlessly and unnecessarily remind an offender of a wrong he may have committed against him. He cannot only forgive, he can forget; and he strives for that nobleness of self and mildness of character which imparts sufficient strength to let the past be but the past. A true man of honor feels humbled himself when he cannot help humbling others.- "Definition of a Gentleman", a memorandum found in his papers after his death, as quoted in Lee the American (1912) by Gamaliel Bradford, p. 233

- I have fought against the people of the North because I believed they were seeking to wrest from the South its dearest rights. But I have never cherished toward them bitter or vindictive feelings, and have never seen the day when I did not pray for them.

- As quoted in The American Soul: An Appreciation of the Four Greatest Americans and their Lessons for Present Americans (1920) by Charles Sherwood Farriss, p. 63

- Obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character.

- As quoted in General Robert E. Lee After Appomattox (1922), by Franklin Lafayette Riley, p. 18

- After it is all over, as stupid a fellow as I am can see that mistakes were made. I notice, however, that my mistakes are never told me until it is too late, and you, and all my officers, know that I am always ready and anxious to have their suggestions.

- Remark to General Henry Heth, as quoted in R. E. Lee : A Biography, Vol. 3 (1935) by Douglas Southall Freeman

- Teach him he must deny himself.

- Lee to a mother who asked him to bless her son, as quoted in R. E. Lee : A Biography, Vol. 4 (1935) by Douglas Southall Freeman, p. 505

- I should NOT be trading on the blood of my men.

- On refusing requests to write his memoirs, as quoted in Gentlemen of Virginia (1961) page 188 by Marshall William Fishwick; also cited as possibly apocryphal in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (2004) edited by Elizabeth M. Knowles

- The education of a man is never completed until he dies.

- As quoted in Peter's Quotations: Ideas for Our Time (1977) by Laurence J. Peter, p. 175

- You must be frank with the world; frankness is the child of honesty and courage. Say just what you mean to do on every occasion, and take it for granted you mean to do right … Never do anything wrong to make a friend or keep one; the man who requires you to do so, is dearly purchased at a sacrifice. Deal kindly, but firmly with all your classmates; you will find it the policy which wears best. Above all do not appear to others what you are not.

- As quoted in Extraordinary Lives: The Art and Craft of American Biography (1986) by Robert A. Caro and William Knowlton Zinsser. Also quoted in Truman by David McCullough (1992), p. 44, New York: Simon & Schuster.-

- I think it is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the Country, to do all in his power to aid in the restoration of peace and harmony. It is particularly incumbent upon those charged with the instruction of the young to set them an example.

- Letter to trustees, as quoted in "Honoring Lee Anew" (15 July 2014), by David Cox, A Magazine of Student Thought and Opinion

- The duty of its citizens, then, appears to me too plain to admit of doubt. All should unite in honest efforts to obilterate the effects of the war and restore the blessing of peace. They should remain, if possible, in the country; promote harmony and good feeling, qualify themselves to vote and elect to the State and general legislatures wise and patriotic men, who will devote their abilities to the interests of the country and the healing of all dissensions. I have invariably recommended this course since the cessation of hostilities, and have endeavored to practice it myself.

- Letter to Governor Letcher

1850s

- The Abolitionist... must see that he has neither the right or power of operating except by moral means and suasion.

- Speech in the Senate (3 March 1854); Quoted in Douglas Southall Freeman (2008) Lee, p. 93

- In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.

- Letter to his wife, Mary Anne Lee (27 December 1856)

1860s

- Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South, I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native State?

- Life and Campaigns of General Robert E. Lee (1866) page 30. Responding to Francis Preston Blair after he relayed an offer to make Lee major-general to command the defense of Washington D.C.

- You see what a poor sinner I am, and how unworthy to possess what was given me; for that reason, it has been taken away.

- Letter to his daughter after losing Arlington (25 December 1861)

- I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, and I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation. I hope, therefore, that all constitutional means will be exhausted before there is a resort to force. Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our Constitution never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation, and surrounded it with so many guards and securities, if it was intended to be broken by every member of the Confederacy at will. It is intended for 'perpetual Union,' so expressed in the preamble, and for the establishment of a government, not a compact, which can only be dissolved by revolution, or the consent of all the people in convention assembled. It is idle to talk of secession: anarchy would have been established, and not a government, by Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, and all the other patriots of the Revolution. … Still, a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me. I shall mourn for my country and for the welfare and progress of mankind. If the Union is dissolved and the Government disrupted, I shall return to my native State and share the miseries of my people, and, save in defense will draw my sword on none.

- Letter to his son, G. W. Custis Lee (23 January 1861).

- Since my interview with you on the 18th I have felt that I ought not longer retain my commission in the Army … It would have been presented at once, but for the struggle, it has cost me to separate myself from a service to which I have devoted all the best years of my life, and all the ability I possessed … I shall carry with me to the grave the most grateful recollections of your kind consideration and your name and fame will always be dear to me. Save for defense of my native state, I never desire again to draw my sword.

- Letter to General Winfield Scott (20 April 1861) after turning down an offer by Abraham Lincoln of supreme command of the U.S. Army; as quoted in Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (1875) by John William Jones, p. 139

- It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it.

- Comment to James Longstreet, on seeing a Union charge repelled in the Battle of Fredericksburg (13 December 1862)

- What a cruel thing is war; to separate and destroy families and friends, and mar the purest joys and happiness God has granted us in this world; to fill our hearts with hatred instead of love for our neighbors, and to devastate the fair face of this beautiful world! I pray that, on this day when only peace and good-will are preached to mankind, better thoughts may fill the hearts of our enemies and turn them to peace. … My heart bleeds at the death of every one of our gallant men.

- Letter to his wife on Christmas Day, two weeks after the Battle of Fredericksburg (25 December 1862).

- Negroes belonging to our citizens are not considered subjects of exchange and were not included in my proposition.

- To Ulysses S. Grant on why black U.S. soldiers were not be repatriated by the Confederacy, as quoted in Liberty, Equality, Power: Enhanced Concise Edition (2009), California: Cengage Learning, p. 433

- I have been up to see the Congress and they do not seem to be able to do anything except to eat peanuts and chew tobacco, while my army is starving.

- Remark to his son, G. W. Custis Lee (March 1865), as quoted in South Atlantic Quarterly [Durham, North Carolina] (July 1927)

- We must consider its effect on the country as a whole. Already it is demoralized by the four years of war. If I took your advice, the men would be without rations and under no control of officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live. They would become mere bands of marauders, and the enemy's cavalry would pursue them and overrun many wide sections they may never have occasion to visit. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from...And as for myself, you young fellows might go bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be to go to General Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences of my acts.

- In response to Brigadier General Edward Porter Alexander (April 1865) after the Battle of Appomattox Court House. Alexander had suggested for Confederate soldiers to disperse, report under orders to their respective governors, and continue fighting the Union. He admitted that he was silenced by Lee's rebuke. "I had not a single word to say in reply. He had answered my suggestion from a plane so far above it that I was ashamed for having made it." as quoted in Fighting For the Confederacy, pp. 531-33[1] and The Methodist Quarterly Review, January 1920 pp. 325-26[2]

- I am glad to see one real American here.

- To Ely S. Parker at Appomattox Court House (9 April 1865), as quoted in The Life of General Ely S. Parker: Last Grand Sachem of the Iroquois and General Grant's Military Secretary Buffalo, by Arthur C. Parker, New York: Buffalo Historical Society, 1919, p. 133

- The only question on which we did not agree has been settled, and the Lord has decided against me.

- To Marsena Patrick, as quoted in "Honoring Lee Anew" (15 July 2014), by David Cox, A Magazine of Student Thought and Opinion

- I, Robert E. Lee of Lexington, Virginia do solemn, in the presence of Almighty God, that I will henceforth faithfully support, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States, the Union of the States thereafter, and that I will, in like manner, abide by and faithful support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion with reference to the emancipation of slaves, so help me God.

- Amnesty oath to the United States (2 October 1865)

- The questions which for years were in dispute between the State and General Government, and which unhappily were not decided by the dictates of reason, but referred to the decision of war, having been decided against us, it is the part of wisdom to acquiesce in the result, and of candor to recognize the fact.

- Letter to former Virginia governor John Letcher (28 August 1865), as quoted in Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (1875) by John William Jones, p. 203

- The interests of the State are therefore the same as those of the United States. Its prosperity will rise or fall with the welfare of the country. The duty of its citizens, then, appears to me too plain to admit of doubt. All should unite in honest efforts to obliterate the effects of war, and to restore the blessings of peace. They should remain, if possible, in the country; promote harmony and good feeling; qualify themselves to vote; and elect to the State and general Legislatures wise and patriotic men, who will devote their abilities to the interests of the country, and the healing of all dissensions. I have invariably recommended this course since the cessation of hostilities, and have endeavored to practice it myself.

- Letter to former Virginia governor John Letcher (28 August 1865), as quoted in Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (1875) by John William Jones, p. 203

- True patriotism sometimes requires of men to act exactly contrary, at one period, to that which it does at another, and the motive which impels them — the desire to do right — is precisely the same.

- Letter to General P.G.T. Beauregard (3 October 1865)

- I think it would be better for Virginia if she could get rid of them. That is no new opinion with me. I have always thought so, and have always been in favor of emancipation - gradual emancipation.

- Testimony to the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction (17 February 1866) responding to a question on relocating freed slaves to other states as quoted in Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction at the First Session Thirty-Ninth Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1866), pp. 135-6.

- I am of the opinion that all who can should vote for the most intelligent, honest, and conscientious men eligible to office, irrespective of former party opinions, who will endeavour to make the new constitutions and the laws passed under them as beneficial as possible to the true interests, prosperity, and liberty of all classes and conditions of the people.

- Letter to General James Longstreet (29 October 1867), as quoted in Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (1924), p. 269.

- My engagements will not permit me to be present, and I believe if there I could not add anything material to the information existing on the subject. I think it wiser, moreover, not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the example of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered.

- Letter regarding war monuments (1869), as quoted in Personal reminiscences, anecdotes, and letters of gen. Robert E. Lee (1874), by John William Jones, p. 234. Also quoted in "Renounce the battle flag: Don't whitewash history" (26 June 2015), by Petula Dvorak, The Washington Post, Washington, D.C. This quote is also given as: "I think it wisest not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the example of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, and to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered."

- My experience through life has convinced me that, while moderation and temperance in all things are commendable and beneficial, abstinence from spirituous liquors is the best safeguard of morals and health.

- Letter to a "Friends of Temperance" society (9 December 1869); as quoted in Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee (1875) by John William Jones, p. 170

1870s

- "Honesty in its widest sense is always admirable. The trite saying that 'honesty is the best policy' has met with the just criticism that honesty is not policy. The seems to be true. The real honest man is honest from conviction of what is right, not from policy."

- "Memoirs of Robert E. Lee" by A. L. Long (1886)

- "Those who oppose our purposes are not always to be regarded as our enemies. We usually think and act from our immediate surroundings. The better rule is to judge our adversaries from their standpoint, not from ours."

- "Memoirs of Robert E. Lee" by A. L. Long (1886)

- So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I have rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be great for the interests of the south. So fully am I satisfied with this, as regards Virginia especially, that I would cheerfully have lost all I have lost by the war, and have suffered all I have suffered, to have this object attained.

- Statement to John Leyburn (1 May 1870), as quoted in R. E. Lee: A Biography (1934) by Douglas Southall Freeman.

- My experience of men has neither disposed me to think worse of them or indisposed me to serve them; nor in spite of failures, which I lament, of errors which I now see and acknowledge; or of the present aspect of affairs; do I despair of the future.

The truth is this: The march of Providence is so slow, and our desires so impatient; the work of progress is so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long, that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing wave and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us to hope.- Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Charles Marshall (September 1870)

- Fold it up and put it away.

- Not verified. The apparent source is this op-ed in the Roanoke Times, dated 14 July 2014, by David Cox (who was rector of R. E. Lee Memorial (Episcopal) Church in Lexington from 1987-2000):

- "Someone wrote me of a woman asking Lee what to do with an old battle flag. Lee supposedly responded, 'Fold it up and put it away.' Though I’ve not verified the account, it is consistent with his letters and acts of his last years. He was always looking ahead."

- Not verified. The apparent source is this op-ed in the Roanoke Times, dated 14 July 2014, by David Cox (who was rector of R. E. Lee Memorial (Episcopal) Church in Lexington from 1987-2000):

- Duty is the sublimest word in our language. Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more. You should never wish to do less.

- Letter purportedly written to his son, G. W. Custis Lee (5 April 1852); published in The New York Sun (26 November 1864). Although the “Duty Letter” was presumed authentic for many decades and included in many biographies of Lee, it was repudiated in December 1864 by “a source entitled to know.” This repudiation was rediscovered by University of Virginia law professor Charles A. Graves who verified that the letter was inconsistent with Lee's biographical facts and letter-writing style. Lee's son also wrote to Graves that he did not recall ever receiving such a letter. “The Forged Letter of General Robert E. Lee”, Proceedings of the 26th annual meeting of the Virginia State Bar Association 17:176 (1914)

- Governor, if I had foreseen the use those people designed to make of their victory, there would have been no surrender at Appomattox Courthouse; no sir, not by me. Had I foreseen these results of subjugation, I would have preferred to die at Appomattox with my brave men, my sword in my right hand.

- Supposedly made to Governor Fletcher S. Stockdale (September 1870), as quoted in The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney, pp. 497-500; however, most major researchers including Douglas Southall Freeman, Shelby Dade Foote, Jr., and Bruce Catton consider the quote a myth and refuse to recognize it. “T. C. Johnson: Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney, 498 ff. Doctor Dabney was not present and received his account of the meeting from Governor Stockdale. The latter told Dabney that he was the last to leave the room, and that as he was saying good-bye, Lee closed the door, thanked him for what he had said and added: "Governor, if I had foreseen the use these people desired to make of their victory, there would have been no surrender at Appomattox, no, sir, not by me. Had I foreseen these results of subjugation, I would have preferred to die at Appomattox with my brave men, my sword in this right hand." This, of course, is second-hand testimony. There is nothing in Lee's own writings and nothing in direct quotation by first-hand witness that accords with such an expression on his part. The nearest approach to it is the claim by H. Gerald Smythe that "Major Talcott" — presumably Colonel T. M. R. Talcott — told him Lee stated he would never have surrendered the army if he had known how the South would have been treated. Mr. Smythe stated that Colonel Talcott replied, "Well, General, you have only to blow the bugle," whereupon Lee is alleged to have answered, "It is too late now" (29 Confederate Veteran, 7). Here again the evidence is not direct. The writer of this biography, talking often with Colonel Talcott, never heard him narrate this incident or suggest in any way that Lee accepted the results of the radical policy otherwise than with indignation, yet in the belief that the extremists would not always remain in office”.

- Tell Hill he must come up … Strike the tent.

- Reported as his last words. There are suggestions that Lee's biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman embellished Lee's final moments; as Lee suffered a stroke on September 28, 1870. Dying two weeks later, on October 12, 1870, shortly after 9 a.m. from the effects of pneumonia. Lee's stroke had resulted in Aphasia, rendering him unable to speak. When interviewed the four attending physicians and family stated "he had not spoken since 28 September..."

- Sorted alphabetically by author or source

- General Lee now rode up and down the lines encouraging the men and ordering them to hold their fire until the enemy came within full range. He seemed, as I thought, to manifest some uneasiness. As he was passing by my company he told the men to keep cool. They turned round and laughed at him. His face reddened a little and with a smile he remarked, "Boys, I believe you are cooler than I am; you need no encouragement." Someone told him he had better dismount or he would be shot. He replied that he had been in seventeen battles and he was not born to be killed by a d----d Yankee.

- Flavel Clingan Barber, Holding The Line: The Third Tennessee Infantry (1994), p. 82.

- Robert E. Lee once said 'it is good that war is terrible, otherwise men would grow fond of it.' This is not an issue upon which we should have war. Our people do not need to bleed the color of red Georgia clay. This is an issue that demands cool heads and moderate positions. Preserving our past, but also preserving our future. And not allowing the hope of partisan advantage to prohibit the healing of our people.

- Roy Barnes, speech to the Georgian House of Representatives (24 January 2001), by R. Barnes, Georgia

- Under genial Southern skies, were reared the families that brought forth in America the two outstanding pietists of the nineteenth century, Robert E. Lee, whose lips were never profaned by an oath, whiskey, or tobacco, and Stonewall Jackson, who opened every battle with a prayer.

- Charles Beard, 1935

- Being a student at the Virginia Military Institute during the Civil War was both good and bad. The good part was knowing that General Lee and the leaders of the Confederacy were counting on you to help train troops for the fighting and to become an officer yourself once you finished your schooling. The bad part was that the wait to get out and fight was so terribly long and you couldn't help worrying that by the time you got old enough, the whole war would be over and you would have missed all the excitement.

- Susan Provost Beller, Cadets at War: The True Story of Teenage Heroism at the Battle of New Market (1991), p. 15

- I think that's progress. I think that represents Americans coming to recognize what those statues were erected for. They weren't erected as memorials for the war. They were very much erected as symbols of Jim Crow, as symbols of white supremacy. I think it's the public beginning to come to the recognition that public space is ours to shape. Right? That when we put up memorials or monuments, we are trying to present a particular memory of the past that we want to remember. And do we want to remember, honor a past where someone like Robert E. Lee was a central figure, a figure of esteem?

- Jamelle Bouie Interview (2020) responding to the question "this week we had the governor of Virginia talk about taking down Lee in the capital of the Confederacy. Isn't that progress?"

- Few casual acquaintances, knowing the gentle yet unbending character of Robert E. Lee in performance of his duties, could guess the intense struggle that this valiant hero of the War Between the States had waged with himself at the outset of those hostilities. Lee, a professional soldier of the highest attainments, had been suggested as commander of the United States forces. In a tumult of feeling he had refused command of the Federal Army and resigned his commission for "I cannot raise my hand against my birthplace..." so setting himself free to serve his native Virginia.

- Lamont Buchanan, A Pictorial History of the Confederacy (1951), p. 41

- Lee, of course, was Lee. A South which had respected him, then come to adore him, now worshiped him. He was a man who grew in stature even as the cause for which he fought became less prosperous. The intensely religious Stonewall Jackson cared little for the glamor and trappings of war but believed in its righteousness with a fierceness that almost frightened those who did not know him. Comparatively, Lee was a gentle man with a mind that could not help seeing both sides of all controversies. Jackson first had to "see the right," then hell's fury could not deter him. Different as these two men were, they got along well, and each had great respect for the other. And when Lee was to hear of the wound to Jackson that later proved fatal, he wrote: "You have lost your left arm, but I have lost my right."

- Lamont Buchanan, A Pictorial History of the Confederacy (1951), p. 99

- Even some of the most vitriolic in the North had respect and downright admiration for Robert E. Lee. Accordingly, his image would turn up regularly in Northern journals, underlined "The Rebel General," in some such pose as holding his field glass in oe hand while resting the other on his sword. In his middle fifties when the war broke out, Lee, just under six feet in height, made a fine appearance and carried with him wherever he went what was described as "an aura of grandeur." Lee once remarked modestly to a worshipful attendant that he felt he was only as good as the generals with whom he could surround himself.

- Lamont Buchanan, A Pictorial History of the Confederacy (1951), p. 119

- Robert E. Lee carried two banners toward fame and immortality. First, as a soldier, he was a leader of supreme ability, highly successful by any measure of that profession. Second, he was a man of great mental capacity, of rare integrity and spiritual force. There are those historians who believe Lee suspected from the beginning that the cause of the South was virtually hopeless. He was certainly a man who by intellectual gift had to see a fact for what it was without disguising reality behind wishful thought. Yet once he had carefully examined his conscience and chosen his course, he wholeheartedly dedicated all his great military wisdom and intuition to further the Confederate cause. General Lee emerged from the War Between the States not as a vanquished commander, but as one of the great heroes of American history, and the admiration felt for him throughout the North was no less sincere than the affection he inspired among all people in the South. Other men fell from favor on both sides. The two Presidents, Davis and Lincoln, were vilified in their own camp, as well as the enemy's. Other commanders, North and South alike, knew the bite of severe, persistent criticism. Even Grant and Sherman, finally to translate the overwhelming numerical and superiority of the North into victory, were not immune. But Lee rode serenely along, respected even by those who opposed the cause he served.

- Lamont Buchanan, A Pictorial History of the Confederacy (1951), p. 261

- The birthday of General Lee is not, I take it, for us an occasion of mourning or of sadness, but rather of pride and glorifying. His career ended in defeat, but it was not failure. His life is not a subject of sadness, but of inspiration. Before it I feel myself utterly unable to do justice to this occasion. I can add nothing to what has been said, but may touch a few points that to me loom as the highest in General Lee and the cause for which he stood.

First, as a man. Above all who took part in that great struggle, Lee best represented his cause. In the field and in battle his soldiers were content, loved simply to look at him in silent admiration and reverence. His own people and the whole world, even his late enemies, now do the same. I say late enemies, for he has no more. They look, I say, largely in silence, because no man has yet been found equal to the expression of this man's character. All who have tried it have come away feeling that they have fallen far short and that silence would almost have been better. The man has found no interpreter; all that has been interpreted he has interpreted in himself, his own figure. This, it seems to me, is his wonderful characteristic as a man in history.

Again, as a soldier and a leader. To him alone of all the leaders that the war produced on both sides the word 'matchless' has applied. That is true, but he is matchless among more than the leaders of his time; he is matchless, unique among the military leaders of all time. Alexander, Hannibal, Napoleon, Gustavus Adolphus, Frederick the Great, Von Moltke- all had their systems of warfare that have been expounded and followed by succeeding generations of soldiers. Lee had his system; military men see and study it in his campaigns, but he alone has practiced it, he alone has dared to practice it. He stands thus in the annals of great soldier leaders, as Colonel Swift says, 'without apostles and with imitators,' matchless, unique.

Third, as an American. Of an old, distinguished, aristocratic family, he was yet a democrat, the outstanding characteristic of an American. The proof is that he went with his people, he was guided by his people, and to the very best of his ability he executed the will of the people. An aristocrat, and yet a democrat; a paradox, but a fact. At the battle of the Wilderness, as leader of a trained, and, for its size, perhaps the most effective army ever created, he tries to fight in person beside his soldiers. I have seen the spot, marked by a little stone which wisely repeats only the words of his soldiers: 'Lee to the rear.'

In all his capacities- as man, as leader, as American- he is to be regarded as you soldiers regard him, in reverent and mainly silent admiration.- Robert Lee Bullard in a 1921 speech to the New York Camp of Confederate Veterans at their annual event honoring Robert E. Lee's birthday at the Hotel Astor in New York City, on 19 January 1921. As quoted by Greg Eanes, Heritage of Honor: Our Confederate Military Legacy (2015), p. 83-85

- When Robert E Lee surrendered the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis was upset about it.

He said "How dare that man resent an order

From the president of the Confederate States of America"

Then somebody told him that General Lee had made the decision himself

In order to save lives because he felt that the battle comin' up

Would cost about twenty thousand lives on both sides

And he said two hundred and forty thousand dead already is enough.

So this song is not about the North or the South but about the bloody brother war

Brother against brother father against son the war that nobody won

And for all those lives that were saved I gotta say: God bless Robert E. Lee.- Johnny Cash, in his song "God Bless Robert E. Lee" from the album Johnny 99 (1983).

- Well the mansion where the General used to live is burning down

Cotton fields are blue with Sherman's troops

I overheard a Yankee say yesterday Nashville fell

So I'm on my way to join the fight General Lee might need my help

But look away look away Dixie I don't want them to see

What they're doing to my Dixie God bless Robert E. Lee.- Johnny Cash, in his song "God Bless Robert E. Lee" from the album Johnny 99 (1983).

- Opposing Grant and the Army of the Potomac was Robert E. Lee, the last great knight of battle. He was a god to his men and a scourge to his antagonists.

- Bruce Catton, The Army of the Potomac: A Stillness at Appomattox (1953) on the dust jacket of the 1953 hardcover edition.

- Robert E. Lee's armies took special care to enslave free blacks during their northern campaign.

- The proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began. It is to me a source of deep mortification and regret to see the name of that good and great man and soldier, General R. E. Lee, given as authority for such a policy. My first hour of despondency will be the one in which that policy shall be adopted. You cannot make soldiers of slaves, nor slaves of soldiers. The moment you resort to negro soldiers your white soldiers will be lost to you; and one secret of the favor with which the proposition is received in portions of the army is the hope that when negroes go into the Army they will be permitted to retire. It is simply a proposition to fight the balance of the war with negro troops. You can't keep white and black troops together, and you can't trust negroes by themselves. It is difficult to get negroes enough for the purpose indicated in the President's message, much less enough for an Army. Use all the negroes you can get, for all the purposes for which you need them, but don't arm them. The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong. But they won't make soldiers. As a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier. Better by far to yield to the demands of England and France and abolish slavery and thereby purchase their aid, than resort to this policy, which leads as certainly to ruin and subjugation as it is adopted; you want more soldiers, and hence the proposition to take negroes into the Army. Before resorting to it, at least try every reasonable mode of getting white soldiers. I do not entertain a doubt that you can, by the volunteering policy, get more men into the service than you can arm. I have more fears about arms than about men, For Heaven’s sake, try it before you fill with gloom and despondency the hearts of many of our truest and most devoted men, by resort to the suicidal policy of arming our slaves.

- Howell Cobb, regarding suggestions that the Confederates turn their slaves into soldiers (1865). As quoted in Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), Hugh Chisholm, editor, 11th ed., Cambridge University Press. Also quoted as 'You cannot make soldiers of slaves, or slaves of soldiers. The day you make a soldier of them is the beginning of the end of the Revolution. And if slaves seem good soldiers, then our whole theory of slavery is wrong'.

- On Palm Sunday, at Appomattox Court House, the spirit of feudalism, of aristocracy, of injustice in this country, surrendered, in the person of Robert E. Lee, the Virginian slave-holder, to the spirit of the Declaration of Independence and of equal rights, in the person of Ulysses S. Grant, the Illinois tanner. So closed this great campaign in the 'Good Fight of Liberty'. So the Army of the Potomac, often baffled, struck an immortal blow, and gave the right hand of heroic fellowship to their brethren of the west. So the silent captain, when all his lieutenants had secured their separate fame, put on the crown of victory and ended civil war. As fought the Lieutenant-General of the United States, so fight the United States themselves, in the 'Good Fight of Man'. With Grant's tenacity, his patience, his promptness, his tranquil faith, let us assault the new front of the old enemy. We, too, must push through the enemy's Wilderness, holding every point we gain. We, too, must charge at daybreak upon his Spottsylvania Heights. We, too, must flank his angry lines and push them steadily back. We, too, must fling ourselves against the baffling flames of Cold Harbor. We, too, outwitting him by night, must throw our whole force across swamp and river, and stand entrenched before his capital. And we, too, at last, on some soft, auspicious day of spring, loosening all our shining lines, and bursting with wild battle music and universal shout of victory over the last desperate defense, must occupy the very citadel of caste, force the old enemy to final and unconditional surrender, and bring Boston and Charleston to sing Te Deum together for the triumphant equal rights of man.

- Like some tall cliff against whose solid base the angry waves are beating, and on whose massive breast the dark storm clouds are spread stands our Lee, with eternal sunshine on his good, grey head. Passing years have not dwarfed him. The new generation joins the remnant of his heroic followers in thanking God for the gift of Lee….We hail thee, thou best loved son of the South, and ranged round thee are thy people, their very hearts thy rampart.

- Bishop Collins Denny, 1906

- It is ridiculous to seek to excuse Robert Lee as the most formidable agency this nation ever raised to make 4 million human beings goods instead of men. Either he knew what slavery meant when he helped maim and murder thousands in its defense, or he did not. If he did not he was a fool. If he did, Robert Lee was a traitor and a rebel–not indeed to his country, but to humanity and humanity’s God.

- W E B Du Bois, Essay on Robert E. Lee (1928)

- General Robert E. Lee's birthday on January 19th has been a holiday in the Commonwealth of Virginia since 1890. It was a day of remembrance for General Lee and later Stonewall Jackson whose birthday is the 21st of January. Lee's personal life was inspiring and even today provides lessons for us all:

-As a citizen, during the challenges of the post [period], Lee advocated patience and reconciliation urging the veterans of the Confederate armies to turn their swords into proverbial ploughshares and help rebuild their communities;

-As an educator, he assumed the Presidency of a financially strapped Washington College, established new and modern courses of study, and focused on developing young men to be good citizens, Christians and leaders in rebuilding an economically devastated South;

-As a father, Lee communicated with his children often- advocating personal discipline, duty and responsibility. Stern at times, he was also tender and affectionate to their feelings;

As a veteran, he wanted to document the heroic struggle of the Army of Northern Virginia to achieve Southern Independence and ensure the sacrifices of his men would not be forgotten or misinterpreted in history. In a letter to Jubal Early, Lee wrote, "My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity, and do justice to our brave Soldiers."- Greg Eanes, Heritage of Honor: Our Confederate Military Legacy (2015), p. 1-2

- Lee and Jackson came to symbolize their men, a devotion to the principles of Constitutional liberty, and the heroic defense of their homeland; concepts for which they and their men were willing to leave their families and surrender their lives. Their consciously made sacrifices are an example to be enshrined and emulated.

- Greg Eanes, Heritage of Honor: Our Confederate Military Legacy (2015), p. 3

- General Robert E. Lee was, in my estimation, one of the supremely gifted men produced by our Nation. He believed unswervingly in the Constitutional validity of his cause which until 1865 was still an arguable question in America; he was a poised and inspiring leader, true to the high trust reposed in him by millions of his fellow citizens; he was thoughtful yet demanding of his officers and men, forbearing with captured enemies but ingenious, unrelenting and personally courageous in battle, and never disheartened by a reverse or obstacle. Through all his many trials, he remained selfless almost to a fault and unfailing in his faith in God. Taken altogether, he was noble as a leader and as a man, and unsullied as I read the pages of our history.…From deep conviction, I simply say this: a nation of men of Lee’s calibre would be unconquerable in spirit and soul. Indeed, to the degree that present-day American youth will strive to emulate his rare qualities, including his devotion to this land as revealed in his painstaking efforts to help heal the Nation’s wounds once the bitter struggle was over, we, in our own time of danger in a divided world, will be strengthened and our love of freedom sustained.

- Dwight Eisenhower, 1960

- Notwithstanding he was among the vanquished, Robert E. Lee is the South’s most revered hero. This circumstance indicates Southerners believe an individual has his grandest hour when he bravely fights against great odds for a lost cause he deems just.

- United States Senator Sam Ervin, Jr., 1984

- Robert E. Lee was one of the small company of great men in whom there is no inconsistency to be explained, no enigma to be solved. What he seemed, he was—a wholly human gentleman, the essential elements of whose positive character were two and only two, simplicity and spirituality.

- Douglas Southall Freeman, 1936

- Oh, I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do. Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command, and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.

- Ulysses S. Grant, as quoted in "Campaigning with Grant" (December 1896), by General Horace Porter, The Century Magazine

- Lee, the result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C.S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

- Ulysses S. Grant, letter to Robert E. Lee (7 April 1865)

- I had known General Lee in the old army, and had served with him in the Mexican War; but did not suppose, owing to the difference in our age and rank, that he would remember me, while I would more naturally remember him distinctly, because he was the chief of staff of General Scott in the Mexican War. When I had left camp that morning I had not expected so soon the result that was then taking place, and consequently was in rough garb. I was without a sword, as I usually was when on horseback on the field, and wore a soldier's blouse for a coat, with the shoulder straps of my rank to indicate to the army who I was. When I went into the house I found General Lee. We greeted each other, and after shaking hands took our seats. I had my staff with me, a good portion of whom were in the room during the whole of the interview. What General Lee's feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of General U. S. Grant (1885), Ch. 67

- He was a large man, a handsome man of commanding presence, with a grave face, lighted by a rarely sweet and winning smile. Men looked up to him, loved him, fought for him. General Scott made no secret of his opinion that Lee was the best of American soldiers—and that long before the outbreak of the War Between the States.

- Robert Selph Henry, 1936

- He was a foe without hate; a friend without treachery; a soldier without cruelty; a victor without oppression, and a victim without murmuring. He was a public officer without vices; a private citizen without wrong; a neighbour without reproach; a Christian without hypocrisy, and a man without guile. He was a Caesar, without his ambition; Frederick, without his tyranny; Napoleon, without his selfishness, and Washington, without his reward.

- Benjamin Harvey Hill, U.S. Congressman from 1875 to 1882, in an address before the Southern Historical Society, Atlanta, Georgia, February 18, 1874. As quoted in Senator Benjamin H. Hill of Georgia; His Life, Speeches and Writings (1893) by Benjamin Harvey Hill Jr., p. 406

- This noble man died 'a prisoner of war on parole'. His application for 'amnesty' was never granted, or even noticed, and the commonest privileges of citizenship which are accorded to the most ignorant negro were denied to this king of men.

- I would tell you that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man. He was a man that gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was always loyalty to state first back in those days. Now it’s different today. But the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War, and men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had them make their stand.

- General Lee directs me to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 25th inst: and to say that he much regrets the unwillingness of owners to permit their slaves to enter the service. If the state authorities can do nothing to get those negroes who are willing to join the army, but whose masters refuse their consent, there is no authority to do it at all. What benefit they expect their negroes to be to them, if the enemy occupies the country, it is impossible to say. He hopes you will endeavor to get the assistance of citizens who favor the measure, and bring every influence you can to bear. When a negro is willing, and his master objects, there would be less objection to compulsion, if the state has the authority. It is however of primary importance that the negroes should know that the service is voluntary on their part. As to the name of the troops, the general thinks you cannot do better than consult the men themselves. His only objection to calling them colored troops was that the enemy had selected that designation for theirs. But this has no weight against the choice of the troops and he recommends that they be called colored or if they prefer, they can be called simply Confederate troops or volunteers. Everything should be done to impress them with the responsibility and character of their position, and while of course due respect and subordination should be exacted, they should be so treated as to feel that their obligations are those of any other soldier and their rights and privileges dependent in law & order as obligations upon others as upon theirselves. Harshness and contemptuous or offensive language or conduct to them must be forbidden and they should be made to forget as soon as possible that they were regarded as menials. You will readily understand however how to conciliate their good will & elevate the tone and character of the men….

- Lt. Col. Charles Marshall, in a letter of 27 March 1865, communicating the thoughts of Lee to Confederate General Richard Ewell, with regards to the attempt to enlist negro troops into the Confederate Army. This is clear evidence that the General did challenge his prior prejudices towards Black Americans to entertain more progressive ones.

- Lee at Gettysburg who decided to attack, attack, attack, even though he knew that it was going to result in thousands of deaths. He made that decision because he thought it necessary in order to win that battle. And in turn perhaps to win the war, to accomplish his objectives. It's not quite so crude as 'the end justifies the means', but I think that all of these extremely difficult decisions, which in the context of a war do mean life and death for tens of thousands of people or destruction of property and the ruin of lives, were made on the grounds of absolute necessity in a crisis situation, not only a war but in some respects a revolutionary situation. The same kinds of things I suppose could be applied to any of the great revolutions in history, the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, and so on.

- James M. McPherson, as quoted in "An exchange with a Civil War historian" (19 June 1995), by David Walsh, International Workers Bulletin

- The strategically insignificant Battle of Seven Pines had momentous consequences. Johnston was badly wounded, and on June 1 Davis appointed Lee to replace him. Nothing in the new commander's Civil War experience foretold the fame he would achieve leading the Army of Northern Virginia to destruction, and to immortality in military annals. Like Grant at Belmont, Lee began on an unpromising note. He was sent to oust the Federals from western Virginia; his strategy miscarried, and troops derisively called him "Granny Lee" and "Evacuating Lee". While commanding the southern Atlantic coast, he earned another unflattering nickname, "the King of Spades," by ordering his men to dig entrenchments. No nicknames have been less apt, because Lee's early wartime activities concealed his true character.

- Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States From 1607 to 2012 (2012), p. 172

- No general surpassed him in audacity and aggressiveness. If McClellan took no risks, Lee perhaps took too many. He preferred the bold offensive, seeking in true Napoleonic fashion to destroy, not merely defeat, the enemy army. Dedicated to winning a battle of annihilation, he sometimes imprudently continued attacking beyond any reasonable prospect of success. Lee also needed to broaden his view of the war. Exhibiting a narrow parochialism, he believed Virginia was the most important war zone. He underestimated the problems Confederate commanders faced in the western and trans-Mississippi theaters and the significance of those theaters for southern survival. Yet Lee served the South well. Although costing the Confederacy dearly, his victories against great odds buoyed Confederate morale and depressed the North. Furthermore, Lee's emphasis on his native state was not entirely emotional. Richmond, the South's primary industrial center, acquired great symbolic value, and the Virginia countryside furnished men, mounts, food, and other logistical assets.

- Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States From 1607 to 2012 (2012), p. 172

- Washington and Grant and Lee were all tried and true

- Eisenhower, Bradley, and MacArthur, too

- They will live forevermore, 'till the world is done with war

- Then they'll close that final door, fading away

- Vaughan Monroe, in his 1951 song "Old Soldiers Never Die", which was named after a famous speech by Douglas MacArthur.

- Lee's problem, wrote the British military historian Sir Liddell Hart, was that he always went on the attack. A wiser course might have been to combine defensive strategy with defensive tactics, "to lure the Union armies into attacking under disadvantageous conditions." He was a general who "would rather lose the war than his dignity." Sure enough, he lost the war and preserved his dignity so well that he has gone down in history a martyr, our most overrated general.

- Seymour Morris Jr., American History Revised: 200 Startling Facts That Never Made It into the Textbooks (2010), p. 160

- Whereas Grant and Sherman had no compunctions about laying waste to farms and doing harm to civilians standing in their way, Lee did. "It is well that war is so terrible," he said, "lest we grow too fond of it." As his armies advanced northward and captured farms, he instructed his soldiers that whatever food they took from the farmers, they pay for it. He, not Grant, won the moral advantage recognized by history.

- Seymour Morris Jr., American History Revised: 200 Startling Facts That Never Made It into the Textbooks (2010), p. 161

- Had he been the Northern general, Lee- like George Washington, a Southerner presiding over a Northern country- would have been in a unique position to bridge the gap between the two sides and unify a war-torn nation. Worshipped by his men, he exuded calm leadership. Nominated for U.S. President in 1868, he would have made a far better president than his wartime opponent, Ulysses Grant. As it turned out, the bitterness of the defeated Southerners because of Grant's and Sherman's slash-and-burn methods resonated for a full century- a long time for America.

- Seymour Morris Jr., American History Revised: 200 Startling Facts That Never Made It into the Textbooks (2010), p. 161

- Theodore Roosevelt, certainly a serious student of history and able to see both sides, being a Northerner with a Southern mother, said Robert E. Lee was our greatest American. Winston Churchill, even more adept at history, said the same. So, too, did Eisenhower. In a 1954 speech to the Boy Scouts of America, President Eisenhower cited Lee as one of his heroes.

- Seymour Morris Jr., American History Revised: 200 Startling Facts That Never Made It into the Textbooks (2010), p. 161

- They had found a leader, Robert E. Lee—and what a leader! Fifty-five years old, tall, handsome, with graying hair and deep, expressive brown eyes which could convey with a glance a stronger reproof than any other general’s oath-laden castigation; kind at heart and courteous even to those who failed him, he inspired and deserved confidence. No military leader since Napoleon has aroused such enthusiastic devotion among troops as did Lee when he reviewed them on his horse Traveller. And, what a horse!

- Samuel Elliot Morrison, 1965

- We were immediately taken before General Lee, who demanded the reason why we ran away. We frankly told him that we considered ourselves free. He then told us he would teach us a lesson we never would forget. He then ordered us to the barn, where, in his presence, we were tied firmly to posts by a Mister Gwin, our overseer, who was ordered by General Lee to strip us to the waist and give us fifty lashes each, excepting my sister, who received but twenty. We were accordingly stripped to the skin by the overseer, who, however, had sufficient humanity to decline whipping us. Accordingly Dick Williams, a county constable, was called in, who gave us the number of lashes ordered. General Lee, in the meantime, stood by, and frequently enjoined Williams to lay it on well, an injunction which he did not fail to heed. Not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, General Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done. * The evidence consisting against this account includes the testimony in 1863 in the Boston Liberator in Lee's defense, in addition that Amanda Parks, sister of one of the two accompanying escaped slaves with Norris tried to visit Lee in Washington in 1866, and failing to meet him at his hotel, later wrote him. Her letter has not survived but the General's response has and the nature of the content, combined with her attempted voluntary meeting with the man who would have whipped her brother, throws a considerable doubt upon the Norris account.

- Wesley Norris testimony (1866), as quoted in Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, and Interviews, and Autobiographies, edited by John W. Blassingame, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, pp. 467-468

- That old man had my division slaughtered at Gettysburg.

- George Pickett, as quoted in The Civil War: An Illustrated History, p. 236

- I am very happy to take part in this unveiling of the statue of General Robert E. Lee. All over the United States we recognize him as a great leader of men, as a great general. But, also, all over the United States I believe that we recognize him as something much more important than that. We recognize Robert E. Lee as one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.

- So it was in the civil war. Farragut's father was born in Spain and Sheridan's father in Ireland; Sherman and Thomas were of English and Custer of German descent; and Grant came of a long line of American ancestors whose original home had been Scotland. But the Admiral was not a Spanish-American; and the Generals were not Scotch-Americans or Irish-Americans or English-Americans or German-Americans. They were all Americans and nothing else. This was just as true of Lee and of Stonewall Jackson and of Beauregard.

- Theodore Roosevelt, "Address to the Knights of Columbus" (12 October 1915)

- Lee is the greatest military genius in America, myself not excepted.

- Winfield Scott, Union general, as quoted in Life of General Robert Edward Lee (1870), by C. Stoctly Errickson, p. 35\

- One of the foundations of the Lost Cause myth was the near deification of Robert E. Lee as the perfect example of an educated Christian gentleman. A Marble Man without sin. Much of my life led me to glorify Robert E. Lee and Confederate soldiers. My first book, my first movie, my hometown, my college, even the U.S. Army and West Point honored Lee and his cause. I hope this book exposes the lies I grew up believing and why it took so long for me to see the evidence, the facts, that I now see so clearly. Eleven southern states seceded to protect and expand an African American slave labor system. Unwilling to accept the results of a fair, democratic election, they illegally seized U.S. territory, violently. Together, they formed a new "Confederacy," in contravention of the U.S. Constitution. Then West Point graduates like Robert E. Lee resigned their commissions, abrogating an oath sworn to God to defend the United States. During the bloodiest war in American history, Lee and his comrades killed more U.S. Army soldiers than any other enemy, ever. And they did it for the worst reason possible: to create a nation dedicated to exploit enslaved men, women, and children, forever.

- Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause (2020), p. 8-9

- As a retired U.S. Army soldier and as a historian, I consider the issue simple. My former hero, Robert E. Lee, committed treason to preserve slavery. After the Civil War, former Confederates, their children, and their grandchildren created a series of myths and lies to hide the essential truth and sustain a racial hierarchy dedicated to white political power reinforced by violence. But for decades, I believed the Confederates and Lee were romantic warriors of a doomed but noble cause. As a soldier, a scholar, and a southerner, I believe that American history demands, at least from me, a reckoning.

- Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause (2020), p. 9

- Lee had beaten or ordered his own slaves to be beaten for the crime of wanting to be free; he fought for the preservation of slavery; his army kidnapped free black people at gunpoint and made them unfree—but all of this, he insisted, had occurred only because of the great Christian love the South held for black Americans. Here we truly understand Frederick Douglass’s admonition that “between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.”

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point (2021)

- There are former Confederates who sought to redeem themselves—one thinks of James Longstreet, wrongly blamed by Lost Causers for Lee’s disastrous defeat at Gettysburg, who went from fighting the Union army to leading New Orleans’s integrated police force in battle against white-supremacist paramilitaries. But there are no statues of Longstreet in New Orleans. Lee was devoted to defending the principle of white supremacy; Longstreet was not. This, perhaps, is why Lee was placed atop the largest Confederate monument at Gettysburg in 1917, but the 6-foot-2-inch Longstreet had to wait until 1998 to receive a smaller-scale statue hidden in the woods that makes him look like a hobbit riding a donkey. It’s why Lee is remembered as a hero, and Longstreet is remembered as a disgrace.

- Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point (2021)

- Although Lee was an enthusiastic and hardworking officer, his promotions in the Army came slowly. Sometimes he may have been discouraged, but he never gave up. His work as an Army engineer was outstanding, but it was in the Mexican War that he distinguished himself in combat. His commander, General Winfield Scott, praised him highly. His reputation as a soldier grew with the years. Just after Lincoln's call for troops, he was offered command of the Union Army. This was the highest goal that any American officer could reach, but Robert E. Lee refused to accept it. Lee's conscience would not permit him to bear arms against his native state. He resigned from the United States Army. Lee's loyalty to the Union was great, but his loyalty to Virginia was greater. He did not want to fight against the United States, but if duty required him to defend his native state, he was determined to do so. When Virginia chose him as the commander of her forces, he accepted the offer on April 23, 1861, and threw all his talents into her defense. Robert E. Lee represented the best of Virginia's traditions and ideals.

- Francis Butler Simkins, Spotswood Hunnicutt, Sidman P. Poole, Virginia: History, Government, Geography (1957), p. 411-412

- In 1864, black Union troops were involved in operations against Lee's army outside Richmond and Petersburg, and some of them are taken prisoner. Lee puts them to work on Confederate entrenchments that are in Union free-fire zones. When Grant gets wind of this, he threatens to put Confederate prisoners to work on Union entrenchments under Confederate fire unless Lee pulls out. So Grant was willing to embrace an eye-for-an-eye, tooth-for-a-tooth retaliation policy based upon Confederate treatment of black prisoners. For Grant, it was the color of the uniform, not the skin, that mattered... The Lee myth. Lee being above slavery, Lee being in fact anti-slavery, is essential to the neo-Confederate argument that it's not about race, it's not about slavery. They've done a very good job of covering up Robert E. Lee's actual positions on this... In pre-war correspondence, Lee castigated the abolitionists for their political activity, and he never showed any qualms about the social order that he would later defend with arms. He also had a few slaves that he inherited as part of a will agreement, with provisions to emancipate those slaves. But in fact, he dragged his heels in complying with the terms of that will. And he never gave a second thought to the fact that his beloved Arlington mansion was run by slave labor.

- Once we understand that the flags in question are those of an army, we can have a more intelligent discussion about what those armies did, such as the fact that the Army of Northern Virginia was under orders to capture and send south supposed escaped slaves during that army's invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863./ That is a question of correctly understanding that since the adoption of the US Constitution in 1787 with the 3/5 and Fugitive Slave tenets, all Commissioned US officers, in swearing to uphold the constitution, swore to uphold the institution, via these tenets, regardless of personal sentiments, including all future Northern officers. William T. Sherman wrote his brother of this from Florida in 1842.

- Brooks D. Simpson, "The Soldiers' Flag?" (5 July 2015), Crossroads

- I think Stone Mountain is amusing, but then again I find most representations of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson outside of Virginia, and, in Jackson's case, West Virginia, to be amusing. Aside from a short period in 1861-62, when Lee was placed in charge of the coastal defense of South Carolina and Georgia, neither general stepped foot in Georgia during the war. Lee cut off furloughs to Georgia's soldiers later in the war because he was convinced that once home they'd never come back. He resisted the dispatch of James Longstreet's two divisions westward to defend northern Georgia, and he had no answer when Sherman operated in the state. It would be better to see Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood on the mountain, although it probably would have been difficult to get those two men to ride together. Maybe Braxton Bragg would have been a better pick, but no one calls him the hero of Chickamauga. Yet Bragg, Johnston, and Hood all attempted to defend Georgia, and they are ignored on Stone Mountain. So is Joe Wheeler, whose cavalry feasted off Georgians in 1864. So is John B. Gordon, wartime hero and postwar Klansman. Given Stone Mountain's history, Klansman Gordon would have been a good choice.

- Brooks D. Simpson, "The Future of Stone Mountain" (22 July 2015), Crossroads

- This week it's Robert E. Lee. I noticed that Stonewall Jackson is coming down. I wonder, is it George Washington next week, and is it Thomas Jefferson the week after? You know, you really do have to ask yourself, where does it stop?

- * Returning home on leave following my second year at West Point, I called on a great-uncle who had joined the Confederate Army at the age of sixteen and had fought in a number of major Civil War battles, including Gettysburg, and had been with Robert E. Lee at Appamatox. My Uncle White was the younger brother of my grandfather. He hated Yankees and Republicans, not necessarily in that order, and talked derisively about both. When I visited, he was seated in a wheel chair, in grudging acquiescence to the infirmities of age. Tobacco juice decorated his shirt and stains around a spittoon on the floor testified to the inaccuracy of his aim. Flies buzzed through screenless windows. "What are you doing with yourself, son?" Uncle White asked. I answered the old veteran with trepidation. "I'm going to that same school that Grant and Sherman went to, the Military Academy at West Point, New York." Uncle White was silent for what seemed like a long time. "That's all right, son," he said at last. "Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson went there too."

- William Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports (1976), p. 12

- Lee was the last of the great old-fashioned generals.

- T. Harry Williams, McClellan, Sherman, and Grant, p. 109

- Works by Robert E. Lee at Project Gutenberg

- Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (1904) by Captain Robert E. Lee, His Son

- R. E. Lee : A Biography (1934) by Douglas Southall Freeman

- Brief biography by Stanley L. Klos

- Robert E. Lee - Virginia Monument at Gettysburg

- Obituary in The New York Times (13 October 1870)

- ↑ Alexander, Fighting for the Confederacy, pp. 531–33.

- ↑ Error on call to Template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. The Methodist Quarterly Review, January 1920 P. 325-326.

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.