Loading AI tools

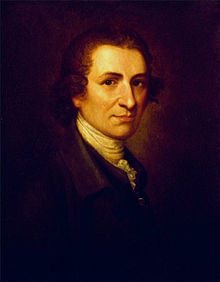

Thomas Paine (February 9, 1737 [O.S. January 29, 1736] – 8 June 1809) was a British-American political writer, theorist, and activist who had a great influence on the thoughts and ideas which led to the American Revolution and the United States Declaration of Independence. He wrote three of the most influential and controversial works of the 18th Century: Common Sense, Rights of Man, and The Age of Reason. His ideas reflected Enlightenment-era ideals of transnational human rights.

1770s

- Eloquence may strike the ear, but the language of poverty strikes the heart; the first may charm like music, but the second alarms like a knell.

- Case of the Excise Officers, (1772)

- This sacrifice of common sense is the certain badge which distinguishes slavery from freedom; for when men yield up the privilege of thinking, the last shadow of liberty quits the horizon.

- Reflections on Titles, (1775)

- He who dares not offend cannot be honest.

- The Forester's Letters, Letter III—'To Cato', Pennsylvania Journal (24 April 1776)

- A man who is so exceedingly civil that for the sake of quietude and a peaceable name will silently see the community imposed upon, or their rights invaded, may, in his principles, be a good man, but cannot be stiled a useful one, neither does he come up to the full mark of his duty; for silence becomes a kind of crime when it operates as a cover or an encouragement to the guilty.

- Pennsylvania Packet, (January 23, 1779)

African Slavery in America (March 1775)

Disputed authorship, included in publication where Paine was editor

- TO AMERICANS. THAT some desperate wretches should be willing to steal and enslave men by violence and murder for gain, is rather lamentable than strange. But that many civilized, nay, christianized people should approve, and be concerned in the savage practice, is surprising; and still persist, though it has been so often proved contrary to the light of nature, to every principle of Justice and Humanity, and even good policy, by a succession of eminent men, and several late publications.

- Our Traders in MEN (an unnatural commodity!) must know the wickedness of that SLAVE-TRADE, if they attend to reasoning, or the dictates of their own hearts; and such as shun and stiffle all these, wilfully sacrifice Conscience, and the character of integrity to that golden Idol.

- The Managers of that Trade themselves, and others, testify, that many of these African nations inhabit fertile countries, are industrious farmers, enjoy plenty, and lived quietly, averse to war, before the Europeans debauched them with liquors, and bribing them against one another; and that these inoffensive people are brought into slavery, by stealing them, tempting Kings to sell subjects, which they can have no right to do, and hiring one tribe to war against another, in order to catch prisoners. By such wicked and inhuman ways the English are said to enslave towards one hundred thousand yearly; of which thirty thousand are supposed to die by barbarous treatment in the first year; besides all that are slain in the unnatural wars excited to take them. So much innocent blood have the Managers and Supporters of this inhuman Trade to answer for to the common Lord of all!

- Many of these were not prisoners of war, and redeemed from savage conquerors, as some plead; and they who were such prisoners, the English, who promote the war for that very end, are the guilty authors of their being so; and if they were redeemed, as is alleged, they would owe nothing to the redeemer but what he paid for them.

- They show as little Reason as Conscience who put the matter by with saying—"Men, in some cases, are lawfully made Slaves, and why may not these?" So men, in some cases, are lawfully put to death, deprived of their goods, without their consent; may any man, therefore, be treated so, without any conviction of desert? Nor is this plea mended by adding—"They are set forth to us as slaves, and we buy them without farther inquiry, let the sellers see to it." Such men may as well join with a known band of robbers, buy their ill-got goods, and help on the trade; ignorance is no more pleadable in one case than the other; the sellers plainly own how they obtain them. But none can lawfully buy without evidence that they are not concurring with Men-Stealers; and as the true owner has a right to reclaim his goods that were stolen, and sold; so the slave, who is proper owner of his freedom, has a right to reclaim it, however often sold.

- Most shocking of all is alledging the Sacred Scriptures to favour this wicked practice. One would have thought none but infidel cavillers would endeavour to make them appear contrary to the plain dictates of natural light, and Conscience, in a matter of common Justice and Humanity; which they cannot be. Such worthy men, as referred to before, judged otherways; Mr. BAXTER declared, the Slave-Traders should be called Devils, rather than Christians; and that it is a heinous crime to buy them. But some say, "the practice was permitted to the Jews." To which may be replied,

- The example of the Jews, in many things, may not be imitated by us; they had not only orders to cut off several nations altogether, but if they were obliged to war with others, and conquered them, to cut off every male; they were suffered to use polygamy and divorces, and other things utterly unlawful to us under clearer light.

- The plea is, in a great measure, false; they had no permission to catch and enslave people who never injured them.

- Such arguments ill become us, since the time of reformation came, under Gospel light. All distinctions of nations, and privileges of one above others, are ceased; Christians are taught to account all men their neighbours; and love their neighbours as themselves; and do to all men as they would be done by; to do good to all men; and Man-stealing is ranked with enormous crimes. Is the barbarous enslaving our inoffensive neighbours, and treating them like wild beasts subdued by force, reconcilable with all these Divine precepts? Is this doing to them as we would desire they should do to us? If they could carry off and enslave some thousands of us, would we think it just?—One would almost wish they could for once; it might convince more than Reason, or the Bible.

- As much in vain, perhaps, will they search ancient history for examples of the modern Slave-Trade. Too many nations enslaved the prisoners they took in war. But to go to nations with whom there is no war, who have no way provoked, without farther design of conquest, purely to catch inoffensive people, like wild beasts, for slaves, is an hight of outrage against Humanity and Justice, that seems left by Heathen nations to be practised by pretended Christians. How shameful are all attempts to colour and excuse it!

- As these people are not convicted of forfeiting freedom, they have still a natural, perfect right to it; and the Governments whenever they come should, in justice set them free, and punish those who hold them in slavery.

- So monstrous is the making and keeping them slaves at all, abstracted from the barbarous usage they suffer, and the many evils attending the practice; as selling husbands away from wives, children from parents, and from each other, in violation of sacred and natural ties; and opening the way for adulteries, incests, and many shocking consequences, for all of which the guilty Masters must answer to the final Judge.

- If the slavery of the parents be unjust, much more is their children's; if the parents were justly slaves, yet the children are born free; this is the natural, perfect right of all mankind; they are nothing but a just recompense to those who bring them up: And as much less is commonly spent on them than others, they have a right, in justice, to be proportionably sooner free.

- Certainly one may, with as much reason and decency, plead for murder, robbery, lewdness, and barbarity, as for this practice: They are not more contrary to the natural dictates of Conscience, and feelings of Humanity; nay, they are all comprehended in it.

- But the chief design of this paper is not to disprove it, which many have sufficiently done; but to entreat Americans to consider.

- With what consistency, or decency they complain so loudly of attempts to enslave them, while they hold so many hundred thousands in slavery; and annually enslave many thousands more, without any pretence of authority, or claim upon them?

- How just, how suitable to our crime is the punishment with which Providence threatens us? We have enslaved multitudes, and shed much innocent blood in doing it; and now are threatened with the same. And while other evils are confessed, and bewailed, why not this especially, and publicly; than which no other vice, if all others, has brought so much guilt on the land?

- Whether, then, all ought not immediately to discontinue and renounce it, with grief and abhorrence? Should not every society bear testimony against it, and account obstinate persisters in it bad men, enemies to their country, and exclude them from fellowship; as they often do for much lesser faults?

- The great Question may be—What should be done with those who are enslaved already? To turn the old and infirm free, would be injustice and cruelty; they who enjoyed the labours of their better days should keep, and treat them humanely. As to the rest, let prudent men, with the assistance of legislatures, determine what is practicable for masters, and best for them. Perhaps some could give them lands upon reasonable rent, some, employing them in their labour still, might give them some reasonable allowances for it; so as all may have some property, and fruits of their labours at their own disposal, and be encouraged to industry; the family may live together, and enjoy the natural satisfaction of exercising relative affections and duties, with civil protection, and other advantages, like fellow men. Perhaps they might sometime form useful barrier settlements on the frontiers. Thus they may become interested in the public welfare, and assist in promoting it; instead of being dangerous, as now they are, should any enemy promise them a better condition.

- The past treatment of Africans must naturally fill them with abhorrence of Christians; lead them to think our religion would make them more inhuman savages, if they embraced it; thus the gain of that trade has been pursued in opposition to the Redeemer's cause, and the happiness of men: Are we not, therefore, bound in duty to him and to them to repair these injuries, as far as possible, by taking some proper measures to instruct, not only the slaves here, but the Africans in their own countries? Primitive Christians laboured always to spread their Divine Religion; and this is equally our duty while there is an Heathen nation: But what singular obligations are we under to these injured people!

- These are the sentiments of JUSTICE AND HUMANITY.

Common Sense (1776)

- First published 10 January 1776, the most commonly reproduced edition is the third, published on 14 February 1776. Full text online

- Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness POSITIVELY by uniting our affections, the latter NEGATIVELY by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first a patron, the last a punisher.

- Opening lines.

- Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not YET sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour; a long habit of not thinking a thing WRONG, gives it a superficial appearance of being RIGHT, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason.

- A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. Explanation: Paine explained the need to speak out against a tyrannical power, notably Britain and King George III, because not doing so could be a dangerous action on its own. A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. This first part actually has two sections on its own. In the first half, Paine says it's important to note the “wrongs” that occur when injustices are clear — not doing so gives them the “appearance of being right.” In the second half, he notes that people's first reactions to those complaints are always to side on the side of “custom” — that is, to oppose attacks against institutions.

- But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason. Explanation: Most Americans are not in favor of impeachment at this moment. It's a reaction against a guarded institution — and citizens are going to behave in ways that make it seem they're against the idea, by giving a “defense of custom,” as Paine put it. It should be noted, however, that the same held true for a different president — Richard Nixon. At the onset of investigations, a majority of Americans felt it was a waste of time. As they learned more about his actions as president, the public (including a significant number of Republicans) became more supportive of his ouster.

- Source: Chris Walker (September 25, 2019): A Look Back At Thomas Paine, And Why Impeachment Makes ‘Common’ Sense (Even If You Think It’s A Losing Cause) [Opinion]. In: HillReporter.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019.

- The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances hath, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all Lovers of Mankind are affected, and in the Event of which, their Affections are interested. The laying a Country desolate with Fire and Sword, declaring War against the natural rights of all Mankind, and extirpating the Defenders thereof from the Face of the Earth, is the Concern of every Man to whom Nature hath given the Power of feeling; of which Class, regardless of Party Censure, is the AUTHOR.

- Who the Author of this Production is, is wholly unnecessary to the Public, as the Object for Attention is the DOCTRINE ITSELF, not the MAN. Yet it may not be unnecessary to say, That he is unconnected with any Party, and under no sort of Influence public or private, but the influence of reason and principle.

- Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise. For were the impulses of conscience clear, uniform, and irresistibly obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do by the same prudence which in every other case advises him out of two evils to choose the least. Wherefore, security being the true design and end of government, it unanswerably follows that whatever form thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expence and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others.

- Wherefore, security being the true design and end of government, it unanswerably follows, that whatever FORM thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expense and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others.

- How came the king by a power which the people are afraid to trust, and always obliged to check? Such a power could not be the gift of a wise people, neither can any power, which needs checking, be from God; yet the provision, which the constitution makes, supposes such a power to exist. But the provision is unequal to the task; the means either cannot or will not accomplish the end, and the whole affair is a felo de se; for as the greater weight will always carry up the less, and as all the wheels of a machine are put in motion by one, it only remains to know which power in the constitution has the most weight, for that will govern; and though the others, or a part of them, may clog, or, as the phrase is, check the rapidity of its motion, yet so long as they cannot stop it, their endeavors will be ineffectual; the first moving power will at last have its way, and what it wants in speed is supplied by time.

- Men who look upon themselves born to reign, and others to obey, soon grow insolent; selected from the rest of mankind their minds are early poisoned by importance; and the world they act in differs so materially from the world at large, that they have but little opportunity of knowing its true interest, and when they succeed to the government are frequently the most ignorant and unfit of any throughout the dominions.

- Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

- It is pleasant to observe by what regular gradation we surmount the force of local prejudice as we enlarge our acquaintance with the world.

- O! ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the Old World is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

- When we are planning for posterity, we ought to remember that virtue is not hereditary.

- The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. 'Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent—of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. 'Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed time of continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; The wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

- It is of the utmost danger to society to make it (religion) a party in political disputes.

- Mingling religion with politics may be disavowed and reprobated by every inhabitant of America.

- I bid you farewell, sincerely wishing, that as men and christians, ye may always fully and uninterruptedly enjoy every civil and religious right.

- There is something exceedingly ridiculous in the composition of monarchy; it first excludes a man from the means of information, yet empowers him to act in cases where the highest judgment is required.

- Hereditary succession has no claim. For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have the right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever, and tho' himself might deserve some decent degree of honours of his contemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them.

- I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.

- A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom.

- Society is produced by our wants, and government by wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections, the latter negatively by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first is a patron, the last a punisher. Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil.

- In the early ages of the world, according to the Scripture chronology there were no kings; the consequence of which was, there were no wars; it is the pride of kings which throws mankind into confusion.

- Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, 'tis time to part.

- Government by kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom. It was the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry.

- But where, say some, is the King of America? I'll tell you, friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Great Britain... so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king.

- O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose, not only the tyranny, but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her — Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

- We have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand, and a race of men, perhaps as numerous as all Europe contains, are to receive their portion of freedom from the event of a few months.

- Wherefore, since nothing but blows will do, for God's sake let us come to a final separation.

- Small islands not capable of protecting themselves are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something very absurd in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.

- But there is another and greater distinction for which no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned, and that is, the distinction of men into KINGS and SUBJECTS. Male and female are the distinctions of nature, good and bad the distinctions of heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth enquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.

- I HAVE never met with a man, either in England or America, who hath not confessed his opinion, that a separation between the countries, would take place one time or other: And there is no instance, in which we have shewn less judgment, than in endeavouring to describe, what we call, the ripeness or fitness of the Continent for independance. As all men allow the measure, and vary only in their opinion of the time, let us, in order to remove mistakes, take a general survey of things, and endeavour, if possible, to find out the very time. But we need not go far, the inquiry ceases at once, for, the time hath found us. The general concurrence, the glorious union of all things prove the fact. It is not in numbers, but in unity, that our great strength lies; yet our present numbers are sufficient to repel the force of all the world.

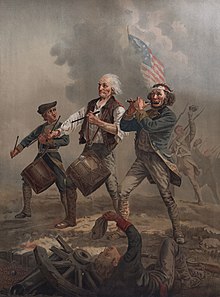

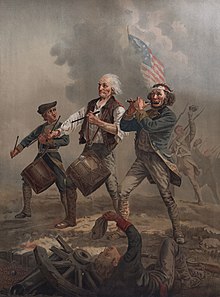

The American Crisis (1776–1783)

- THESE are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.

- The Crisis No. I (written 19 December 1776, published 23 December 1776).

- The Crisis No. I from The American Crisis by Thomas Paine was printed in the Pennsylvania Journal on December 19, 1776. Within a day of its publication, General Washington ordered it be read to his dispirited and suffering troops before his crossing of the Delaware River. Its opening sentence These are the times that try men's souls was adopted as the watchword of the Battle of Trenton on December 26 and is believed to have inspired much of the courage which won that victory. The American Crisis/Editor's Preface

- 'Tis surprising to see how rapidly a panic will sometimes run through a country. All nations and ages have been subject to them. Britain has trembled like an ague at the report of a French fleet of flat-bottomed boats; and in the fourteenth [sic (actually the fifteenth)] century the whole English army, after ravaging the kingdom of France, was driven back like men petrified with fear; and this brave exploit was performed by a few broken forces collected and headed by a woman, Joan of Arc. Would that heaven might inspire some Jersey maid to spirit up her countrymen, and save her fair fellow sufferers from ravage and ravishment! Yet panics, in some cases, have their uses; they produce as much good as hurt. Their duration is always short; the mind soon grows through them, and acquires a firmer habit than before. But their peculiar advantage is, that they are the touchstones of sincerity and hypocrisy, and bring things and men to light, which might otherwise have lain forever undiscovered. In fact, they have the same effect on secret traitors, which an imaginary apparition would have upon a private murderer. They sift out the hidden thoughts of man, and hold them up in public to the world. Many a disguised Tory has lately shown his head, that shall penitentially solemnize with curses the day on which Howe arrived upon the Delaware.

- The Crisis No. I.

- It matters not where you live, or what rank of life you hold, the evil or the blessing will reach you all. The far and the near, the home counties and the back, the rich and the poor, will suffer or rejoice alike. The heart that feels not now is dead; the blood of his children will curse his cowardice, who shrinks back at a time when a little might have saved the whole, and made them happy. I love the man that can smile in trouble, that can gather strength from distress, and grow brave by reflection. 'Tis the business of little minds to shrink; but he whose heart is firm, and whose conscience approves his conduct, will pursue his principles unto death.

My own line of reasoning is to myself as straight and clear as a ray of light. Not all the treasures of the world, so far as I believe, could have induced me to support an offensive war, for I think it murder; but if a thief breaks into my house, burns and destroys my property, and kills or threatens to kill me, or those that are in it, and to "bind me in all cases whatsoever" to his absolute will, am I to suffer it? What signifies it to me, whether he who does it is a king or a common man; my countryman or not my countryman; whether it be done by an individual villain, or an army of them? If we reason to the root of things we shall find no difference; neither can any just cause be assigned why we should punish in the one case and pardon in the other. Let them call me rebel and welcome, I feel no concern from it; but I should suffer the misery of devils, were I to make a whore of my soul by swearing allegiance to one whose character is that of a sottish, stupid, stubborn, worthless, brutish man.- The Crisis No. I.

- I once felt all that kind of anger, which a man ought to feel, against the mean principles that are held by the Tories: a noted one, who kept a tavern at Amboy, was standing at his [[door], with as pretty a child in his hand, about eight or nine years old, as I ever saw, and after speaking his mind as freely as he thought was prudent, finished with this unfatherly expression, "Well! give me peace in my day."

Not a man lives on the continent but fully believes that a separation must some time or other finally take place, and a generous parent should have said, "If there must be trouble, let it be in my day, that my child may have peace;" and this single reflection, well applied, is sufficient to awaken every man to duty.- The Crisis No. I.

- Not a place upon earth might be so happy as America. Her situation is remote from all the wrangling world, and she has nothing to do but to trade with them.

A man can distinguish himself between temper and principle, and I am as confident, as I am that God governs the world, that America will never be happy till she gets clear of foreign dominion. Wars, without ceasing, will break out till that period arrives, and the continent must in the end be conqueror; for though the flame of liberty may sometimes cease to shine, the coal can never expire.- The Crisis No. I.

- Wisdom is not the purchase of a day, and it is no wonder that we should err at the first setting off.

- The Crisis No. I.

- Every Tory is a coward; for servile, slavish, self-interested fear is the foundation of Toryism; and a man under such influence, though he may be cruel, never can be brave.

- The Crisis No. I.

- America could carry on a two years' war by the confiscation of the property of disaffected persons, and be made happy by their expulsion. Say not that this is revenge, call it rather the soft resentment of a suffering people, who, having no object in view but the good of all, have staked their own all upon a seemingly doubtful event. Yet it is folly to argue against determined hardness; eloquence may strike the ear, and the language of sorrow draw forth the tear of compassion, but nothing can reach the heart that is steeled with prejudice.

- The Crisis No. I.

- Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.

- The Crisis No. I, partially quoted by U.S. president Barack Obama in his first inaugural adress.

- Had I served my God as faithful as I have served my king, he would not thus have forsaken me in my old age.

- He that rebels against reason is a real rebel, but he that in defence of reason, rebels against tyranny, has a better title to "defender of the faith" than George the Third.

- The Crisis No. II.

- As politicians we ought not so much to ground our hopes on the reasonableness of the thing we ask, as on the reasonableness of the person of whom we ask it: who would expect discretion from a fool, candor from a tyrant, or justice from a villain?

- All we want to know in America is simply this, who is for independence, and who is not? Those who are for it, will support it, and the remainder will undoubtedly see the reasonableness of paying the charges; while those who oppose or seek to betray it, must expect the more rigid fate of the jail and the gibbet. There is a bastard kind of generosity, which being extended to all men, is as fatal to society, on one hand, as the want of true generosity is on the other. A lax manner of administering justice, falsely termed moderation, has a tendency both to dispirit public virtue, and promote the growth of public evils.

- The Crisis No. III.

- Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom, must, like men, undergo the fatigues of supporting it.

- Men who are sincere in defending their freedom, will always feel concern at every circumstance which seems to make against them; it is the natural and honest consequence of all affectionate attachments, and the want of it is a vice. But the dejection lasts only for a moment; they soon rise out of it with additional vigor; the glow of hope, courage and fortitude, will, in a little time, supply the place of every inferior passion, and kindle the whole heart into heroism.

- The Crisis No. IV.

- There is a mystery in the countenance of some causes, which we have not always present judgment enough to explain. It is distressing to see an enemy advancing into a country, but it is the only place in which we can beat them, and in which we have always beaten them, whenever they made the attempt. The nearer any disease approaches to a crisis, the nearer it is to a cure. Danger and deliverance make their advances together, and it is only the last push, in which one or the other takes the lead.

- The Crisis No. IV.

- You have too much at stake to hesitate. You ought not to think an hour upon the matter, but to spring to action at once. Other states have been invaded, have likewise driven off the invaders. Now our time and turn is come, and perhaps the finishing stroke is reserved for us. When we look back on the dangers we have been saved from, and reflect on the success we have been blessed with, it would be sinful either to be idle or to despair.

- The Crisis No. IV.

- We fight not to enslave, but to set a country free, and to make room upon the earth for honest men to live in.

- The Crisis No. IV.

- To argue with a man who has renounced the use and authority of reason, and whose philosophy consists in holding humanity in contempt, is like administering medicine to the dead, or endeavoring to convert an atheist by scripture.

- He who is the author of a war, lets loose the whole contagion of hell, and opens a vein that bleeds a nation to death.

- The Grecians and Romans were strongly possessed of the spirit of liberty but not the principle, for at the time that they were determined not to be slaves themselves, they employed their power to enslave the rest of mankind.

- The Crisis No. V (1778)

- But when the country, into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears, it was time to stir. It was time for every man to stir.

- "THE times that tried men's souls," are over- and the greatest and completest revolution the world ever knew, gloriously and happily accomplished.

- Our citizenship in the United States is our national character. Our citizenship in any particular state is only our local distinction. By the latter we are known at home, by the former to the world. Our great title is AMERICANS.

- It was the cause of America that made me an author. The force with which it struck my mind and the dangerous condition the country appeared to me in, by courting an impossible and an unnatural reconciliation with those who were determined to reduce her, instead of striking out into the only line that could cement and save her, A Declaration Of Independence, made it impossible for me, feeling as I did, to be silent: and if, in the course of more than seven years, I have rendered her any service, I have likewise added something to the reputation of literature, by freely and disinterestedly employing it in the great cause of mankind, and showing that there may be genius without prostitution. Independence always appeared to me practicable and probable, provided the sentiment of the country could be formed and held to the object: and there is no instance in the world, where a people so extended, and wedded to former habits of thinking, and under such a variety of circumstances, were so instantly and effectually pervaded, by a turn in politics, as in the case of independence; and who supported their opinion, undiminished, through such a succession of good and ill fortune, till they crowned it with success. But as the scenes of war are closed, and every man preparing for home and happier times, I therefore take my leave of the subject. I have most sincerely followed it from beginning to end, and through all its turns and windings: and whatever country I may hereafter be in, I shall always feel an honest pride at the part I have taken and acted, and a gratitude to nature and providence for putting it in my power to be of some use to mankind.

1780s

- War involves in its progress such a train of unforeseen and unsupposed circumstances ... that no human wisdom can calculate the end.

- Prospects on the Rubicon (1787)

1790s

- It is from the Bible that man has learned cruelty, rapine, and murder; for the belief of a cruel God makes a cruel man.

- "A Letter: Being an Answer to a Friend, on the publication of The Age of Reason" (12 May 1797), published in an 1852 edition of The Age of Reason, p. 205

- We think it also necessary to express our astonishment that a government, desirous of being called FREE, should prefer connection with the most despotic and arbitrary powers in Europe.

- we hold that the moral obligation of providing for old age, helpless infancy, and poverty, is far superior to that of supplying the invented wants of courtly extravagance, ambition and intrigue.

- We live to improve, or we live in vain

- As to riots and tumults, let those answer for them, who, by willful misrepresentations, endeavor to excite and promote them; or who seek to stun the sense of the nation, and to lose the great cause of public good in the outrages of a misinformed mob. We take our ground on principles that require no such riotous aid. We have nothing to apprehend from the poor; for we are pleading their cause. And we fear not proud oppression, for we have truth on our side.

- It is error only, and not truth, that shrinks from inquiry.

- The complete political works. Rights of man: being an answer to Mr. Burke's attack on the French Revolution, p. 306

- There ought to be some regulation with respect to the spirit of denunciation that now prevails. If every individual is to indulge his private malignancy or his private ambition, to denounce at random and without any kind of proof, all confidence will be undermined and all authority be destroyed. Calumny is a species of treachery that ought to be punished as well as any other kind of treachery. It is a private vice productive of public evils; because it is possible to irritate men into disaffection by continual calumny who never intended to be disaffected.

It is therefore equally as necessary to guard against the evils of unfounded or malignant suspicion as against the evils of blind confidence. It is equally as necessary to protect the characters of public officers from calumny as it is to punish them for treachery or misconduct.

- One good schoolmaster is of more use than a hundred priests.

- It is a want of feeling to talk of priests and bells while so many infants are perishing in the hospitals, and aged and infirm poor in the streets, from the want of necessaries.

- Why has the Revolution of France been stained with crimes, which the Revolution of the United States of America was not? Men are physically the same in all countries; it is education that makes them different. Accustom a people to believe that priests or any other class of men can forgive sins, and you will have sins in abundance.

- Worship and Church Bells (1797)

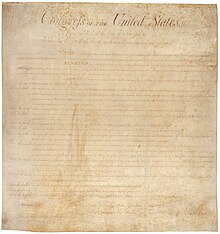

Rights of Man

Part I (1791)

- The people of America had been bred up in the same prejudices against France, which at that time characterized the people of England; but experience and an acquaintance with the French Nation have most effectually shown to the American the falsehood of those prejudices; and I do not believe that a more cordial and confidential intercourse exists between any two countries than between America and France.

- Preface

- It was not against Louis the XVIth, but against the despotic principles of the government, that the nation revolted. These principles had not their origin in him, but in the original establishment, many centuries back; and they were become too deeply rooted to be removed, and the augean stable of parasites and plunderers too abominably filthy to be cleansed, by any thing short of a complete and universal revolution.

- Preface

- When the tongue or the pen is let loose in a phrenzy of passion, it is the man, and not the subject, that becomes exhausted.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- There never did, there never will, and there never can, exist a Parliament, or any description of men, or any generation of men, in any country, possessed of the right or the power of binding and controlling posterity to the "end of time," or of commanding for ever how the world shall be governed, or who shall govern it; and therefore all such clauses, acts or declarations by which the makers of them attempt to do what they have neither the right nor the power to do, nor the power to execute, are in themselves null and void. Every age and generation must be as free to act for itself in all cases as the age and generations which preceded it. The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man; neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The circumstances of the world are continually changing, and the opinions of man change also; and as government is for the living, and not for the dead, it is the living only that has any right in it.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- When it becomes necessary to do anything, the whole heart and soul should go into the measure, or not attempt it.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The mind of the nation was acted upon by a higher stimulus than what the consideration of persons could inspire, and sought a higher conquest than could be produced by the downfall of an enemy.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Lay then the axe to the root, and teach governments humanity. It is their sanguinary punishments which corrupt mankind.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- It is by distortedly exalting some men, that others are distortedly debased, till the whole is out of nature.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- It is to be observed throughout Mr. Burke's book that he never speaks of plots against the Revolution; and it is from those plots that all the mischiefs have arisen. It suits his purpose to exhibit the consequences without their causes. It is one of the arts of the drama to do so. If the crimes of men were exhibited with their sufferings, stage effect would sometimes be lost, and the audience would be inclined to approve where it was intended they should commiserate.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- While the characters of men are forming, as is always the case in revolutions, there is a reciprocal suspicion, and a disposition to misinterpret each other; and even parties directly opposite in principle will sometimes concur in pushing forward the same movement with very different views, and with the hopes of its producing very different consequences. A great deal of this may be discovered in this embarrassed affair, and yet the issue of the whole was what nobody had in view.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Before anything can be reasoned upon to a conclusion, certain facts, principles, or data, to reason from, must be established, admitted, or denied.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Not one glance of compassion, not one commiserating reflection, that I can find throughout his book, has he bestowed on those who lingered out the most wretched of lives, a life without hope in the most miserable of prisons. It is painful to behold a man employing his talents to corrupt himself. Nature has been kinder to Mr. Burke than he is to her. He is not affected by the reality of distress touching his heart, but by the showy resemblance of it striking his imagination. He pities the plumage, but forgets the dying bird. Accustomed to kiss the aristocratical hand that hath purloined him from himself, he degenerates into a composition of art, and the genuine soul of nature forsakes him. His hero or his heroine must be a tragedy-victim expiring in show, and not the real prisoner of misery, sliding into death in the silence of a dungeon.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The duty of man is not a wilderness of turnpike gates, through which he is to pass by tickets from one to the other. It is plain and simple, and consists but of two points. His duty to God, which every man must feel; and with respect to his neighbor, to do as he would be done by. If those to whom power is delegated do well, they will be respected: if not, they will be despised; and with regard to those to whom no power is delegated, but who assume it, the rational world can know nothing of them.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- When I contemplate the natural dignity of man, when I feel (for Nature has not been kind enough to me to blunt my feelings) for the honour and happiness of its character, I become irritated at the attempt to govern mankind by force and fraud, as if they were all knaves and fools, and can scarcely avoid disgust at those who are thus imposed upon.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- To possess ourselves of a clear idea of what government is, or ought to be, we must trace it to its origin. In doing this we shall easily discover that governments must have arisen either out of the people or over the people. Mr. Burke has made no distinction. He investigates nothing to its source, and therefore he confounds everything; but he has signified his intention of undertaking, at some future opportunity, a comparison between the constitution of England and France. As he thus renders it a subject of controversy by throwing the gauntlet, I take him upon his own ground. It is in high challenges that high truths have the right of appearing; and I accept it with the more readiness because it affords me, at the same time, an opportunity of pursuing the subject with respect to governments arising out of society.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- ... like a man being both mortgagor and mortgagee, and in the case of misapplication of trust it is the criminal sitting in judgment upon himself.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- [W]hy do men continue to practise themselves the absurdities they despise in others?

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- It will always happen when a thing is originally wrong that amendments do not make it right, and it oftens happens that they do as much mischief one way as good the other...

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Titles are but nick-names, and every nickname is a title. The thing is perfectly harmless in itself, but it marks a sort of foppery in the human character, which degrades it. It reduces man into the diminutive of man in things which are great, and the counterfeit of women in things which are little. It talks about its fine blue ribbon like a girl, and shows its new garter like a child. A certain writer, of some antiquity, says: "When I was a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things."

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The genuine mind of man, thirsting for its native home, society contemns the gewgaws that separate him from it. Titles are like circles drawn by the magician's wand, to contract the sphere of man's felicity.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Imagination has given figure and character to centaurs, satyrs, and down to all the fairy tribe; but titles baffle even the powers of fancy, and are a chimerical non-descript.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The world has seen this folly fall, and it has fallen by being laughed at, and the farce of titles will follow its fate. The patriots of France have discovered in good time that rank and dignity in society must take a new ground. The old one has fallen through. It must now take the substantial ground of character, instead of the chimerical ground of titles; and they have brought their titles to the altar, and made of them a burnt-offering to Reason.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Aristocracy is kept up by family tyranny and injustice.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- There is an unnatural unfitness in an aristocracy to be legislators for a nation. Their ideas of distributive justice are corrupted at the very source. They begin life trampling on all their younger brothers and sisters, and relations of every kind, and are taught and educated so to do. With what ideas of justice or honor can that man enter a house of legislation, who absorbs in his own person the inheritance of a whole family of children, or metes out some pitiful portion with the insolence of a gift?

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The idea of hereditary legislators is as inconsistent as that of hereditary judges, or hereditary juries; and as absurd as an hereditary mathematician, or an hereditary wise man; and as ridiculous as an hereditary poet-laureat.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- A body of men, holding themselves accountable to nobody, ought not to be trusted by any body.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- [A]ristocracy has a tendency to degenerate the human species.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The greatest characters the world have known have arisen on the democratic floor. Aristocracy has not been able to keep a proportionate pace with democracy.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The artificial noble shrinks into a dwarf before the noble of nature; and in the few instances (for there are some in all countries) in whom nature, as by a miracle, has survived in aristocracy, those men despise it.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Toleration is not the opposite of Intolerance, but is the counterfeit of it. Both are despotisms. The one assumes to itself the right of withholding Liberty of Conscience, and the other of granting it. The one is the Pope armed with fire and faggot, and the other is the Pope selling or granting indulgences. The former is church and state, and the latter is church and traffic.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- With respect to what are called denominations of religion, if every one is left to judge of its own religion, there is no such thing as a religion that is wrong; but if they are to judge of each other's religion, there is no such thing as a religion that is right; and therefore all the world is right, or all the world is wrong. But with respect to religion itself, without regard to names, and as directing itself from the universal family of mankind to the Divine object of all adoration, it is man bringing to his Maker the fruits of his heart; and though those fruits may differ from each other like the fruits of the earth, the grateful tribute of every one is accepted.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- All religions are in their nature kind and benign, and united with principles of morality. They could not have made proselytes at first by professing anything that was vicious, cruel, persecuting, or immoral. Like everything else, they had their beginning; and they proceeded by persuasion, exhortation, and example. How then is it that they lose their native mildness, and become morose and intolerant?

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- [T]he remedy of force can never supply the remedy of reason.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- It is the nature of conquest to turn everything upside down.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- They stand not aloof with the gaping vacuity of vulgar ignorance, nor bend with the cringe of sycophantic insignificance. The graceful pride of truth knows no extremes, and preserves, in every latitude of life, the right-angled character of man.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Submission is wholly a vassalage term, repugnant to the dignity of freedom, and an echo of the language used at the Conquest.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- It is already on the wane, eclipsed by the enlarging orb of reason, and the luminous revolutions of America and France.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The difference between a republican and a courtier with respect to monarchy, is that the one opposes monarchy, believing it to be something; and the other laughs at it, knowing it to be nothing.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Voltaire, who was both the flatterer and the satirist of despotism, took another line. His force lay in exposing and ridiculing the superstitions which priest-craft, united with state-craft, had interwoven with governments. It was not from the purity of his principles, or his love of mankind (for satire and philanthropy are not naturally concordant), but from his strong capacity of seeing folly in its true shape, and his irresistible propensity to expose it, that he made those attacks. They were, however, as formidable as if the motive had been virtuous; and he merits the thanks rather than the esteem of mankind.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Man cannot, properly speaking, make circumstances for his purpose, but he always has it in his power to improve them when they occur...

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- I [...] could not avoid reflecting how wretched was the condition of a disrespected man.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- The election that followed, was not a contested election, but an animated one. The candidates were not men, but principles. Societies were formed in Paris, and committees of correspondence and communication established throughout the nation, for the purpose of enlightening the people, and explaining to them the principles of civil government; and so orderly was the election conducted, that it did not give rise even to the rumor of tumult.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- They began to consider the Aristocracy as a kind of fungus growing out of the corruption of society, that could not be admitted even as a branch of it...

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- It lost ground from contempt more than from hatred; and was rather jeered at as an ass, than dreaded as a lion. This is the general character of aristocracy, or what are called Nobles or Nobility, or rather No-ability, in all countries.

- Part 1.3 Rights of Man

- Whatever is my right as a man is also the right of another; and it becomes my duty to guarantee as well as to possess.

- Part 1.5 Rights of Man

- Reason and Ignorance, the opposites of each other, influence the great bulk of mankind. If either of these can be rendered sufficiently extensive in a country, the machinery of Government goes easily on. Reason obeys itself; and Ignorance submits to whatever is dictated to it.

- Part 1.7 Conclusion

- Man is not the enemy of man, but through the medium of a false system of Government. Instead, therefore, of exclaiming against the ambition of kings, the exclamation should be directed against the principle of such governments; and instead of seeking to reform the individual, the wisdom of a nation should apply itself to reform the system.

- Part 1.7 Conclusion

Part 2 (1792)

- That there are men in all countries who get their living by war, and by keeping up the quarrels of Nations, is as shocking as it is true; but when those who are concerned in the government of a country, make it their study to sow discord and cultivate prejudices between Nations, it becomes the more unpardonable.

- Preface

- Freedom had been hunted round the globe; reason was considered as rebellion; and the slavery of fear had made men afraid to think. But such is the irresistible nature of truth, that all it asks, — and all it wants, — is the liberty of appearing. The sun needs no inscription to distinguish him from darkness; and no sooner did the American governments display themselves to the world, than despotism felt a shock and man began to contemplate redress.

- Part 2.2 Introduction

- If, from the more wretched parts of the old world, we look at those which are in an advanced stage of improvement, we still find the greedy hand of government thrusting itself into every corner and crevice of industry, and grasping the spoil of the multitude. Invention is continually exercised, to furnish new pretenses for revenue and taxation. It watches prosperity as its prey and permits none to escape without tribute.

- Part 2.2 Introduction

- It appears to general observation, that revolutions create genius and talents; but those events do no more than bring them forward. There is existing in man, a mass of sense lying in a dormant state, and which, unless something excites it to action, will descend with him, in that condition, to the grave. As it is to the advantage of society that the whole of its faculties should be employed, the construction of government ought to be such as to bring forward, by a quiet and regular operation, all that extent of capacity which never fails to appear in revolutions.

- Part 2.5 Chapter III. Of the old and new systems of government

- It is on this system that the American government is founded. It is representation ingrafted upon democracy. It has fixed the form by a scale parallel in all cases to the extent of the principle. What Athens was in miniature America will be in magnitude. The one was the wonder of the ancient world; the other is becoming the admiration, the model of the present. It is the easiest of all the forms of government to be understood and the most eligible in practice; and excludes at once the ignorance and insecurity of the hereditary mode, and the inconvenience of the simple democracy.

- Part 2.5 Chapter III. Of the old and new systems of government

- It is ridiculous that nations are to wait and government be interrupted till boys grow to be men.

Whether I have too little sense to see, or too much to be imposed upon; whether I have too much or too little pride, or of anything else, I leave out of the question; but certain it is, that what is called monarchy, always appears to me a silly, contemptible thing. I compare it to something kept behind a curtain, about which there is a great deal of bustle and fuss, and a wonderful air of seeming solemnity; but when, by any accident, the curtain happens to be open — and the company see what it is, they burst into laughter.

- When extraordinary power and extraordinary pay are allotted to any individual in a government, he becomes the center, round which every kind of corruption generates and forms. Give to any man a million a year, and add thereto the power of creating and disposing of places, at the expense of a country, and the liberties of that country are no longer secure. What is called the splendour of a throne is no other than the corruption of the state. It is made up of a band of parasites, living in luxurious indolence, out of the public taxes.

- I speak an open and disinterested language, dictated by no passion but that of humanity. To me, who have not only refused offers, because I thought them improper, but have declined rewards I might with reputation have accepted, it is no wonder that meanness and imposition appear disgustful. Independence is my happiness, and I view things as they are, without regard to place or person; my country is the world, and my religion is to do good.

- Part 2.7 Chapter V. Ways and means of improving the condition of Europe, interspersed with miscellaneous observations

- When it shall be said in any country in the world, my poor are happy; neither ignorance nor distress is to be found among them; my jails are empty of prisoners, my streets of beggars; the aged are not in want, the taxes are not oppressive; the rational world is my friend, because I am a friend of its happiness: When these things can be said, then may the country boast of its constitution and its government.

- Part 2.7 Chapter V. Ways and means of improving the condition of Europe, interspersed with miscellaneous observations

- A constitution is the property of a nation, and not of those who exercise the government. All the constitutions of America are declared to be established on the authority of the people. In France, the word nation is used istead of the people; but in both cases, a constitution is a thing antecedent to the government, and always distinct therefrom.

- Part Two, Chapter III

- Magna Charta, as it was called... was no more compelling the government to renounce a part of its assumptions. It did not create and give powers to government in the manner a constitution does; but was, as far as it went, of the nature of a re-conquest, and not of a constitution; for could the nation have totally expelled the usurpation, as France has done its despotism, it would then have had a constitution to form.

- Part Two, Chapter III

- Peace, which costs nothing, is attended with infinitely more advantage, than any victory with all its expence.

- Part Two, Chapter V. Ways and means of improving the condition of Europe, interspersed with miscellaneous observations.

Letter to the Addressers (1792)

- And the final event to himself has been, that, as he rose like a rocket, he fell like the stick.

- On Edmund Burke's reactions to the American and French revolutions.

- There are two distinct classes of men in the nation, those who pay taxes, and those who receive and live upon the taxes.

- When the qualification to vote is regulated by years, it is placed on the firmest possible ground, because the qualification is such as nothing but dying before the time can take away; and the equality of Rights, as a principle, is recognized in the act of regulating the exercise. But when Rights are placed upon, or made dependent upon property, they are on the most precarious of all tenures. "Riches make themselves wings, and fly away," and the rights fly with them ; and thus they become lost to the man when they would be of most value.

- It is from a strange mixture of tyranny and cowardice that exclusions have been set up and continued. The boldness to do wrong at first, changes afterwards into cowardly craft, and at last into fear. The Representatives in England appear now to act as if they were afraid to do right, even in part, lest it should awaken the nation to a sense of all the wrongs it has endured. This case serves to shew that the same conduct that best constitutes the safety of an individual, namely, a strict adherence to principle, constitutes also the safety of a Government, and that without it safety is but an empty name. When the rich plunder the poor of his rights, it becomes an example of the poor to plunder the rich of his property, for the rights of the one are as much property to him as wealth is property to the other and the little all is as dear as the much. It is only by setting out on just principles that men are trained to be just to each other; and it will always be found, that when the rich protect the rights of the poor, the poor will protect the property of the rich. But the guarantee, to be effectual, must be parliamentarily reciprocal.

- A thing, moderately good, is not so good as it ought to be. Moderation in temper, is always a virtue; but moderation in principle, is a species of vice.

The Age of Reason

Part I (1794)

- I have always strenuously supported the Right of every Man to his own opinion, however different that opinion might be to mine. He who denies to another this right, makes a slave of himself to his present opinion, because he precludes himself the right of changing it.

- The most formidable weapon against errors of every kind is Reason. I have never used any other, and I trust I never shall.

- I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe the equality of man, and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavouring to make our fellow creatures happy.

- My own mind is my own church. All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian, or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

- It is necessary to the happiness of man, that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving; it consists in professing to believe what he does not believe.

- It is impossible to calculate the moral mischief, if I may so express it, that mental lying has produced in society. When a man has so far corrupted and prostituted the chastity of his mind, as to subscribe his professional belief to things he does not believe, he has prepared himself for the commission of every other crime.

- Revelation is necessarily limited to the first communication. After this, it is only an account of something which that person says was a revelation made to him; and though he may find himself obliged to believe it, it cannot be incumbent on me to believe it in the same manner, for it was not a revelation made to me, and I have only his word for it that it was made to him.

- The resurrection and ascension, supposing them to have taken place, admitted of public and ocular demonstration, like that of the ascension of a balloon, or the sun at noon day, to all Jerusalem at least. [...] But it appears that Thomas did not believe the resurrection; and, as they say, would not believe without having ocular and manual demonstration himself. So neither will I; and the reason is equally as good for me and for every other person, as for Thomas.

- When we read the obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled, it would be more consistent that we called it the word of a demon, than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness, that has served to corrupt and brutalize mankind; and, for my own part, I sincerely detest it, as I detest every thing that is cruel.

- It is only in the CREATION that all our ideas and conceptions of a word of God can unite. [...] It is an ever existing original, which every man can read. It cannot be forged; it cannot be counterfeited; it cannot be lost; it cannot be altered; it cannot be suppressed. It does not depend upon the will of man whether it shall be published or not; it publishes itself from one end of the earth to the other.

- As to the christian system of faith, it appears to me as a species of atheism; a sort of religious denial of God. [...] It introduces between man and his maker an opaque body which it calls a redeemer; as the moon introduces her opaque self between the earth and the sun, and it produces by this means a religious or an irreligious eclipse of light. It has put the whole orb of reason into shade.

- That which is now called natural philosophy, embracing the whole circle of science, of which astronomy occupies the chief place, is the study of the works of God, and of the power and wisdom of God in his works, and is the true theology. [...] It is not among the least of the mischiefs that the christian system has done to the world, that it has abandoned the original and beautiful system of theology, like a beautiful innocent to distress and reproach, to make room for the hag of superstition.

- There may be many systems of religion, that so far from being morally bad, are in many respects morally good: but there can be but ONE that is true; and that one, necessarily must, as it ever will, be in all things consistent with the ever existing word of God that we behold in his works. But such is the strange construction of the Christian system of faith, that every evidence the heavens affords to man, either directly contradicts it, or renders it absurd.

- Of all the modes of evidence that ever were invented to obtain belief to any system or opinion, to which the name of religion has been given, that of miracle, however successful the imposition may have been, is the most inconsistent. [...] It is also the most equivocal sort of evidence that can be set up; for the belief is not to depend upon the thing called a miracle, but upon the credit of the reporter, who says that he saw it; and, therefore the thing, were it true, would have no better chance of being believed than if it were a lie.

- Moral principle speaks universally for itself. [...] Instead therefore of admitting the recitals of miracles, as evidence of any system of religion being true, they ought to be considered as symptoms of its being fabulous. It is necessary to the full and upright character of truth that it rejects the crutch; and it is consistent with the character of fable, to seek the aid that truth rejects.

Part II (1795)

The Old Testament

- To read the bible without horror, we must undo every thing that is tender, sympathising, and benevolent in the heart of man. Speaking for myself, if I had no other evidence that the bible is fabulous than the sacrifice I must make to believe it to be true, that alone would be sufficient to determine my choice.

- Take away from Genesis the belief that Moses was the author, on which only the strange belief that it is the word of God has stood, and there remains nothing of Genesis but an anonymous book of stories, fables, and traditionary or invented absurdities, or of down-right lies. The story of Eve and the serpent, and of Noah and his ark, drops to a level with the Arabian tales, without the merit of being entertaining; and the account of men living to eight and nine hundred years becomes as fabulous as the immortality of the giants of the mythology.

- People in general know not what wickedness there is in this pretended word of God. Brought up in habits of superstition, they take it for granted, that the bible is true, and that it is good. [...] Good heavens, it is quite another thing! It is a book of lies, wickedness, and blasphemy; for what can be greater blasphemy than to ascribe the wickedness of man to the orders of the Almighty.

- The sublime and the ridiculous are often so nearly related, that it is difficult to class them separately. One step above the sublime makes the ridiculous, and one step above the ridiculous makes the sublime again.

The New Testament

- The story of Jesus Christ appearing after he was dead is the story of an apparition; such as timid imaginations can always create in vision and credulity believe. [...] Once start a ghost and credulity fills up the history of its life, and assigns the cause of its appearance. One tells it one way, another another way, till there are as many stories about the ghost, and about the proprietor of the ghost, as there are about Jesus Christ in these four books.

- There is not the least shadow of evidence of who the persons were that wrote [the books ascribed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John], nor at what time they were written; and they might as well have been called by the names of any of the other supposed apostles as by the names they are now called. The originals are not in the possession of any Christian church existing, any more than the two tables of stone written on, they pretend, by the finger of God, upon mount Sinai and given to Moses, are in the possession of the Jews; and even if they were, there is no possibility of proving the hand writing in either case.

- The doctrine [Paul] sets out to prove by argument, is the resurrection of the same body, and he advances this as an evidence of immortality. [...] This doctrine of the resurrection of the same body, so far from being an evidence of immortality, appears to me to furnish an evidence against it; for if I have already died in this body, and am raised again in the same body in which I have lived, it is a presumptive evidence that I shall die again.

- Every animal in the creation excels us in something. The winged insects, without mentioning doves or eagles, can pass over more space and with greater ease in a few minutes than man can in an hour. [...] Even the sluggish snail can ascend from the bottom of a dungeon, where man, by the want of that ability, would perish, and a spider can launch itself from the top as a playful amusement. The personal powers of man are so limited, and his heavy frame so little constructed to extensive enjoyment, that there is nothing to induce us to wish the opinion of Paul to be true. It is too little for the magnitude of the scene; too mean for the sublimity of the subject.

- The slow and creeping caterpillar-worm of to-day passes in a few days to a torpid figure and a state resembling death; and in the next change comes forth in all the miniature magnificence of life, a splendid butterfly. No resemblance of the former creature remains; everything is changed; all his powers are new, and life is to him another thing. We cannot conceive that the consciousness of existence is not the same in this state of the animal as before; why then must I believe that the resurrection of the same body is necessary to continue to me the consciousness of existence hereafter?

- Credulity [...] is not a crime, but it becomes criminal by resisting conviction. It is strangling in the womb of the conscience the efforts it makes to ascertain truth. We should never force belief upon ourselves in any thing.

Conclusion

- The most detestable wickedness, the most horrid cruelties, and the greatest miseries that have afflicted the human race, have had their origin in this thing called revelation, or revealed religion. It has been the most dishonorable belief against the character of the divinity, the most destructive to morality and the peace and happiness of man, that ever was propagated since man began to exist. It is better, far better, that we admitted, if it were possible, a thousand devils to roam at large, and to preach publicly the doctrine of devils, if there were any such, than that we permitted one such impostor and monster as Moses, Joshua, Samuel, and the bible prophets, to come with the pretended word of God in his mouth, and have credit among us.

- It is incumbent on every man who reverences the character of the Creator, and who wishes to lessen the catalogue of artificial miseries, and remove the cause that has sown persecutions thick among mankind, to expel all ideas of revealed religion, as a dangerous heresy and an impious fraud. What is that we have learned from this pretended thing called revealed religion? Nothing that is useful to man, and every thing that is dishonourable to his Maker.

- Loving of enemies is another dogma of feigned morality, and has besides no meaning. It is incumbent on man as a moralist that he does not revenge an injury; and it is equally as good in a political sense; for there is no end to retaliation; each retaliates on the other, and calls it justice. But to love in proportion to the injury, if it could be done, would be to offer a premium for crime.

- The belief of a God is so weakened by being mixed with the strange fable of the Christian creed, and with the wild adventures related in the bible, and the obscurity and obscene nonsense of the testament, that the mind of man is bewildered as in a fog. [...] The belief of a God is a belief distinct from all other things, and ought not to be confounded with any. The notion of a trinity of gods has enfeebled the belief of one God. A multiplication of beliefs acts as a division of belief, and in proportion as any thing is divided it is weakened.

- Of all the systems of religion that ever were invented, there is none more derogatory to the Almighty, more unedifying to man, more repugnant to reason, and more contradictory in itself than this thing called Christianity. Too absurd for belief, too impossible to convince, and too inconsistent for practice, it renders the heart torpid, or produces only atheists and fanatics. As an engine of power it serves the purpose of despotism; and as a means of wealth, the avarice of priests; but so far as respects the good of man in general, it leads to nothing here or hereafter.

- The only religion that has not been invented, and that has in it every evidence of divine originality, is pure and simple deism. It must have been the first, and will probably be the last that man believes: but pure and simple deism does not answer the purpose of despotic governments. They cannot lay hold of religion as an engine, but by mixing it with human inventions, and making their own authority a part.

- It has been the scheme of the Christian church, and of all the other invented systems of religion, to hold man in ignorance of the Creator, as it is of governments to hold man in ignorance of his rights. The systems of the one are as false as those of the other, and are calculated for mutual support. The study of theology, as it stands in Christian churches, is the study of nothing. It is founded on nothing; it rests on no principles; it proceeds by no authorities; it has no data; it can demonstrate nothing; and it admits of no conclusion.

- If man must preach, let him preach something that is edifying, and from texts that are known to be true. [...] Every part of science, whether connected with the geometry of the universe, with the systems of animal and vegetable life, or with the properties of inanimate matter, is a text as well for devotion as for philosophy; for gratitude, as for human improvement. It will perhaps be said, that if such a revolution in the system of religion takes place, every preacher ought to be a philosopher. Most certainly; and every house of devotion a school of science.

Part III (1807)

- It is the duty of every man, as far as his ability extends, to detect and expose delusion and error. But nature has not given to everyone a talent for that purpose; and among those to whom such a talent is given, there is often a want of disposition or of courage to do it.

- The prejudice of unfounded belief often degenerates into the prejudice of custom, and becomes, at last, rank hypocrisy. When men from custom or fashion, or any worldly motive, profess or pretend to believe what they do not believe, nor can give any reason for believing, they unship the helm of their morality, and being no longer honest to their own minds, they feel no moral difficulty in being unjust to others.

- As in my political works my motive and object have been to give man an elevated sense of his own character, and to free him from the slavish and superstitious absurdity of monarchy and hereditary government; so in my publications on religious subjects, my endeavors have been directed to bring man to a right use of the reason that God has given him; to impress on him the great principles of divine morality, justice, mercy, and a benevolent disposition to all men, and to all creatures, and to inspire in him a spirit of trust, confidence, and consolation in his Creator, unshackled by the fables of books pretending to be the word of God.