Loading AI tools

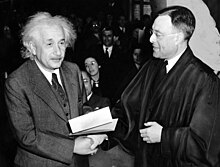

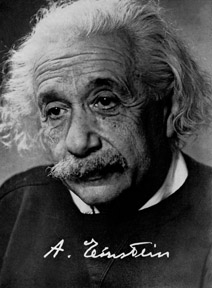

Albert Einstein (14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest physicists of all time. Einstein is known for developing the theory of relativity, but he also made important contributions to the development of the theory of quantum mechanics. Together, relativity and quantum mechanics are the two pillars of modern physics. He won the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect.

1890s

- Un homme heureux est trop content du présent pour trop se soucier de l'avenir.

- A happy man is too satisfied with the present to dwell too much on the future.

- From "Mes Projets d'Avenir", a French essay written at age 17 for a school exam (18 September 1896). The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein Vol. 1 (1987) Doc. 22.

1900s

- Autoritätsdusel ist der größte Feind der Wahrheit.

- Blind obedience to authority is the greatest enemy of truth.

- Another translation: Authority gone to one's head is the greatest enemy of truth. (Collected Papers, Volume 1, 1987)

- Letter to Jost Winteler (July 8th, 1901), quoted in The Private Lives of Albert Einstein by Roger Highfields and Paul Carter (1993), p. 79. Einstein had been annoyed that Paul Drude, editor of Annalen der Physik, had dismissed some criticisms Einstein made of Drude's electron theory of metals.

- Lieber Habicht! / Es herrscht ein weihevolles Stillschweigen zwischen uns, so daß es mir fast wie eine sündige Entweihung vorkommt, wenn ich es jetzt durch ein wenig bedeutsames Gepappel unterbreche... / Was machen Sie denn, Sie eingefrorener Walfisch, Sie getrocknetes, eingebüchstes Stück Seele...?

- Dear Habicht, / Such a solemn air of silence has descended between us that I almost feel as if I am committing a sacrilege when I break it now with some inconsequential babble... / What are you up to, you frozen whale, you smoked, dried, canned piece of soul...?

- Opening of a letter to his friend Conrad Habicht in which he describes his four revolutionary Annus Mirabilis papers (18 or 25 May 1905) Doc. 27

- E = mc²

- The equivalence of mass and energy was originally expressed by the equation m = L/c², which easily translates into the far more well-known E = mc² in Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content? published in the Annalen der Physik (27 September 1905) : "If a body gives off the energy L in the form of radiation, its mass diminishes by L/c²."

- In a later statement explaining the ideas expressed by this equation, Einstein summarized: "It followed from the special theory of relativity that mass and energy are both but different manifestations of the same thing — a somewhat unfamiliar conception for the average mind. Furthermore, the equation E = mc², in which energy is put equal to mass, multiplied by the square of the velocity of light, showed that very small amounts of mass may be converted into a very large amount of energy and vice versa. The mass and energy were in fact equivalent, according to the formula mentioned before. This was demonstrated by Cockcroft and Walton in 1932, experimentally."

- Atomic Physics (1948) by the J. Arthur Rank Organisation, Ltd. (Voice of A. Einstein.)

- The mass of a body is a measure of its energy content.

- Ist die Trägheit eines Körpers von seinem Energieinhalt abhängig? ("Does the inertia of a body depend upon its energy content?")

- Annalen der Physik 18, 639-641 (1905). Quoted in Concepts of Mass in Classical and Modern Physics by Max Jammer (1961), p. 177

- We shall, therefore, assume the complete physical equivalence of a gravitational field and a corresponding acceleration of the reference system.

- Statement of the equivalence principle in Yearbook of Radioactivity and Electronics (1907)

1910s

- Die Natur zeigt uns vom Löwen zwar nur den Schwanz. Aber es ist mir unzweifelhaft, dass der Löwe dazugehört, wenn er sich auch wegen seiner ungeheuren Dimensionen dem Blicke nicht unmittelbar offenbaren kann. Wir sehen ihn nur wie eine Laus, die auf ihm sitzt.

- Nature shows us only the tail of the lion. But there is no doubt in my mind that the lion belongs with it even if he cannot reveal himself to the eye all at once because of his huge dimension. We see him only the way a louse sitting upon him would.

- Letter to Heinrich Zangger (10 March 1914), quoted in The Curious History of Relativity by Jean Eisenstaedt (2006), p. 126.

- Variant: "Nature shows us only the tail of the lion. But I do not doubt that the lion belongs to it even though he cannot at once reveal himself because of his enormous size." As quoted by Abraham Pais in Subtle is the Lord:The Science and Life of Albert Einstein (1982), p. 235 ISBN 0-192-80672-6

- Man begreift schwer beim Erleben dieser "großen Zeit", daß man dieser verrückten, verkommenen Spezies angehört, die sich Willensfreiheit zuschreibt. Wenn es doch irgendwo eine Insel der Wohlwollenden und Besonnenen gäbe! Da wollte ich auch glühender Patriot sein.

- In living through this "great epoch," it is difficult to reconcile oneself to the fact that one belongs to that mad, degenerate species that boasts of its free will. How I wish that somewhere there existed an island for those who are wise and of good will! In such a place even I should be an ardent patriot!

- Letter to Paul Ehrenfest, early December 1914. Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 8, Doc. 39. Quoted in The New Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice (2005), p. 3

- Es ist bequem mit dem Einstein. Jedes Jahr widerruft er, was er das vorige Jahr geschrieben hat.

- It's convenient with that fellow Einstein, every year he retracts what he wrote the year before.

- Letter to Paul Ehrenfest, 26 December 1915. Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 8, Doc. 173.

- How does it happen that a properly endowed natural scientist comes to concern himself with epistemology? Is there not some more valuable work to be done in his specialty? That's what I hear many of my colleagues ask, and I sense it from many more. But I cannot share this sentiment. When I think about the ablest students whom I have encountered in my teaching — that is, those who distinguish themselves by their independence of judgment and not just their quick-wittedness — I can affirm that they had a vigorous interest in epistemology. They happily began discussions about the goals and methods of science, and they showed unequivocally, through tenacious defense of their views, that the subject seemed important to them.

Concepts that have proven useful in ordering things easily achieve such authority over us that we forget their earthly origins and accept them as unalterable givens. [Begriffe, welche sich bei der Ordnung der Dinge als nützlich erwiesen haben, erlangen über uns leicht eine solche Autorität, dass wir ihres irdischen Ursprungs vergessen und sie als unabänderliche Gegebenheiten hinnehmen.] Thus they might come to be stamped as "necessities of thought," "a priori givens," etc. The path of scientific progress is often made impassable for a long time by such errors. [Der Weg des wissenschaftlichen Fortschritts wird durch solche Irrtümer oft für längere Zeit ungangbar gemacht.] Therefore it is by no means an idle game if we become practiced in analysing long-held commonplace concepts and showing the circumstances on which their justification and usefulness depend, and how they have grown up, individually, out of the givens of experience. Thus their excessive authority will be broken. They will be removed if they cannot be properly legitimated, corrected if their correlation with given things be far too superfluous, or replaced if a new system can be established that we prefer for whatever reason.- Obituary for physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach (Nachruf auf Ernst Mach), Physikalische Zeitschrift 17 (1916), p. 101

- ...to the question whether or not the motion of the Earth in space can be made perceptible in terrestrial experiments. We have already remarked... that all attempts of this nature led to a negative result. Before the theory of relativity was put forward, it was difficult to become reconciled to this negative result.

- Relativity – The Special and General Theory (1916), Part I: The Special Theory of Relativity, Experience and the Special Theory of Relativity

- Unser ganzer gepriesener Fortschritt der Technik, überhaupt die Civilisation, ist der Axt in der Hand des pathologischen Verbrechers vergleichbar.

- Our entire much-praised technological progress, and civilization generally, could be compared to an axe in the hand of a pathological criminal.

- Letter to Heinrich Zangger (1917), as quoted in A Sense of the Mysterious: Science and the Human Spirit by Alan Lightman (2005), p. 110, and in Albert Einstein: A Biography by Albrecht Fölsing (1997), p. 399

- Sometimes paraphrased as "Technological progress is like an axe in the hands of a pathological criminal."

- The most beautiful fate of a physical theory is to point the way to the establishment of a more inclusive theory, in which it lives on as a limiting case.

- (1917) as quoted by Gerald Holton, The Advancement of Science, and Its Burdens: the Jefferson Lecture and Other Essays (1986)

- Ich habe auch manchen wissenschaftlichen Plan überlegt, während ich Dich im Kinderwagen spazieren schob!

- I have also considered many scientific plans during my pushing you around in your pram!

- Letter to his son Hans Albert Einstein (June 1918)

- Geh Recht viel spazieren, dass Du Recht gesund wirst und lies nicht gar zu viel sondern spar Dir noch was auf bis Du gross bist.

- Make a lot of walks to get healthy and don't read that much but save yourself some until you're grown up.

- Letter to his son Eduard Einstein (June 1918)

- "The physical world is real." That is supposed to be the fundamental hypothesis. What does "hypothesis" mean here? For me, a hypothesis is a statement, whose truth must be assumed for the moment, but whose meaning must be raised above all ambiguity. The above statement appears to me, however, to be, in itself, meaningless, as if one said: "The physical world is cock-a-doodle-do." It appears to me that the "real" is an intrinsically empty, meaningless category (pigeon hole), whose monstrous importance lies only in the fact that I can do certain things in it and not certain others.

- Letter to Eduard Study, 25 Sept. 1918, in the Einstein Archive, Hebrew U., Jerusalem; translation in D. Howard, Perspectives on Science 1, 225 (1993).

- I lie on the beach like a crocodile and let myself be roasted by the sun. I never see a newspaper and don't give a damn for what is called the world.

- Letter to Max Born, 1918, from The Born-Einstein Letters: Friendship, Politics and Physics in Uncertain Times, Macmillan (2005 edition), pg 7.

- Liebe Mutter! Heute eine freudige Nachricht. H. A. Lorentz hat mir telegraphiert, dass die englischen Expeditionen die Lichtablenkung an der Sonne wirklich bewiesen haben.

- Dear mother! Today a joyful notice. H. A. Lorentz has telegraphed me that the English expeditions have really proven the deflection of light at the sun.

- Postcard to his mother Pauline Einstein (1919)

- Noch eine Art Anwendung des Relativitätsprinzips zum Ergötzen des Lesers: Heute werde ich in Deutschland als "deutscher Gelehrter", in England als "Schweizer Jude" bezeichnet; sollte ich aber einst in die Lage kommen, als "bète noire" präsentiert zu werden, dann wäre ich umgekehrt für die Deutschen ein „Schweizer Jude", für die Engländer ein "deutscher Gelehrter".

- By an application of the theory of relativity to the taste of readers, today in Germany I am called a German man of science, and in England I am represented as a Swiss Jew. If I come to be represented as a bête noire, the descriptions will be reversed, and I shall become a Swiss Jew for the Germans and a German man of science for the English!

- "Einstein On His Theory", The Times (London), 28 November 1919, quoted in Herman Bernstein: Celebrities of Our Time. New York 1924. p. 267 (archive.org). Einstein's original German text in The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. Volume 7. Doc. 25 p. 210, and at germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org after Albert Einstein, Mein Weltbild. Amsterdam: Querido Verlag, 1934, pp. 220-28. Manuscript at alberteinstein.info.

Principles of Research (1918)

- In the temple of science are many mansions, and various indeed are they that dwell therein and the motives that have led them thither. Many take to science out of a joyful sense of superior intellectual power; science is their own special sport to which they look for vivid experience and the satisfaction of ambition; many others are to be found in the temple who have offered the products of their brains on this altar for purely utilitarian purposes. Were an angel of the Lord to come and drive all the people belonging to these two categories out of the temple, the assemblage would be seriously depleted, but there would still be some men, of both present and past times, left inside. Our Planck is one of them, and that is why we love him.

I am quite aware that we have just now lightheartedly expelled in imagination many excellent men who are largely, perhaps chiefly, responsible for the buildings of the temple of science; and in many cases, our angel would find it a pretty ticklish job to decide. But of one thing I feel sure: if the types we have just expelled were the only types there were, the temple would never have come to be, any more than a forest can grow which consists of nothing but creepers. For these people any sphere of human activity will do if it comes to a point; whether they become engineers, officers, tradesmen, or scientists depends on circumstances.

Now let us have another look at those who have found favor with the angel. Most of them are somewhat odd, uncommunicative, solitary fellows, really less like each other, in spite of these common characteristics, than the hosts of the rejected. What has brought them to the temple? That is a difficult question and no single answer will cover it.

- The state of mind which enables a man to do work of this kind is akin to that of the religious worshiper or the lover; the daily effort comes from no deliberate intention or program, but straight from the heart.

- Man tries to make for himself in the fashion that suits him best a simplified and intelligible picture of the world; he then tries to some extent to substitute this cosmos of his for the world of experience, and thus to overcome it. This is what the painter, the poet, the speculative philosopher, and the natural scientist do, each in his own fashion. Each makes this cosmos and its construction the pivot of his emotional life, in order to find in this way the peace and security which he cannot find in the narrow whirlpool of personal experience.

- Variant translation: One of the strongest motives that lead men to art and science is escape from everyday life with its painful crudity and hopeless dreariness, from the fetters of one's own ever-shifting desires. A finely tempered nature longs to escape from the personal life into the world of objective perception and thought. With this negative motive goes a positive one. Man seeks to form for himself, in whatever manner is suitable for him, a simplified and lucid image of the world, and so to overcome the world of experience by striving to replace it to some extent by this image. This is what the painter does, and the poet, the speculative philosopher, the natural scientist, each in his own way. Into this image and its formation, he places the center of gravity of his emotional life, in order to attain the peace and serenity that he cannot find within the narrow confines of swirling personal experience.

- As quoted in The Professor, the Institute, and DNA (1976) by Rene Dubos; also in The Great Influenza (2004) by John M. Barry

- But what can be the attraction of getting to know such a tiny section of nature thoroughly, while one leaves everything subtler and more complex shyly and timidly alone? Does the product of such a modest effort deserve to be called by the proud name of a theory of the universe? In my belief the name is justified; for the general laws on which the structure of theoretical physics is based claim to be valid for any natural phenomenon whatsoever. With them, it ought to be possible to arrive at the description, that is to say, the theory, of every natural process, including life, by means of pure deduction, if that process of deduction were not far beyond the capacity of the human intellect. The physicist's renunciation of completeness for his cosmos is therefore not a matter of fundamental principle.

- The supreme task of the physicist is to arrive at those universal elementary laws from which the cosmos can be built up by pure deduction. There is no logical path to these laws; only intuition, resting on sympathetic understanding of experience, can reach them. In this methodological uncertainty, one might suppose that there were any number of possible systems of theoretical physics all equally well justified; and this opinion is no doubt correct, theoretically. But the development of physics has shown that at any given moment, out of all conceivable constructions, a single one has always proved itself decidedly superior to all the rest.

- Variant, from Preface to Max Planck's Where is Science Going? (1933): The supreme task of the physicist is the discovery of the most general elementary laws from which the world-picture can be deduced logically. But there is no logical way to the discovery of these elemental laws. There is only the way of intuition, which is helped by a feeling for the order lying behind the appearance, and this Einfühlung [literally, empathy or 'feeling one's way in']' is developed by experience.

1920s

More than I could tell with words...

- Wie lieb ich diesen edlen Mann

Mehr als ich mit Worten sagen kann.

Doch fürcht' ich, dass er bleibt allein

Mit seinem strahlenden Heiligenschein.- How much do I love that noble man

More than I could tell with words

I fear though he'll remain alone

With a holy halo of his own. - Poem by Einstein on Spinoza (1920), as quoted in Einstein and Religion by Max Jammer, Princeton UP 1999, p. 43; original German manuscript: "Zu Spinozas Ethik".

- How much do I love that noble man

- We may assume the existence of an aether; only we must give up ascribing a definite state of motion to it, i.e. we must by abstraction take from it the last mechanical characteristic which Lorentz had still left it. ... But this ether may not be thought of as endowed with the quality characteristic of ponderable inedia, as consisting of parts which may be tracked through time. The idea of motion may not be applied to it.

- On the irrelevance of the luminiferous aether hypothesis to physical measurements, in an address at the University of Leiden (5 May 1920)

- I am neither a German citizen nor do I believe in anything that can be described as a "Jewish faith." But I am a Jew and glad to belong to the Jewish people, though I do not regard it in any way as chosen.

- Letter to Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, 3 [5] April 1920, as quoted in Alice Calaprice, The Ultimate Quotable Einstein (2010), p. 195; citing Israelitisches Wochenblatt, 42 September 1920, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 7, Doc. 37, and Vol. 9, Doc 368.

- Es ist das schönste Los einer physikalischen Theorie, wenn sie selbst zur Aufstellung einer umfassenden Theorie den Weg weist, in welcher sie als Grenzfall weiterlebt.

- No fairer destiny could be allotted to any physical theory, than that it should of itself point out the way to the introduction of a more comprehensive theory, in which it lives on as a limiting case.

- Über die spezielle und die allgemeine Relativitätstheorie (1920) Tr. Robert W. Lawson, Relativity: The Special and General Theory (1920) pp. 90-91.

- Raffiniert ist der Herrgott, aber boshaft ist er nicht.

- Subtle is the Lord, but malicious He is not.

- Remark made during Einstein's first visit to Princeton University (April 1921) as quoted in Einstein (1973) by R. W. Clark, Ch. 14. "God is slick, but he ain't mean" is a variant translation of this (1946) Unsourced variant: "God is subtle but he is not malicious."

- When asked what he meant by this he replied. "Nature hides her secret because of her essential loftiness, but not by means of ruse." (Die Natur verbirgt ihr Geheimnis durch die Erhabenheit ihres Wesens, aber nicht durch List.) As quoted in Subtle is the Lord — The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein (1982) by Abraham Pais einsteinandreligion.com

- Originally said to Princeton University mathematics professor Oscar Veblen, May 1921, while Einstein was in Princeton for a series of lectures, upon hearing that an experimental result by Dayton C. Miller of Cleveland, if true, would contradict his theory of gravitation. But the claimed discrepancy was quite small and required special circumstances (hence Einsteins's remark). The result turned out to be false. Some say by this remark Einstein meant that Nature hides her secrets by being subtle, while others say he meant that nature is mischievous but not bent on trickery. [The Yale Book of Quotations, ed. Fred R. Shapiro, 2006]

- Variant translation: God may be sophisticated, but he's not malicious.

- As quoted in Cherished Illusions (2005) by Sarah Stern, p. 109

- I have second thoughts. Maybe God is malicious.

- Said to Valentine Bargmann, as quoted in Einstein in America (1985) by Jamie Sayen, p. 51, indicating that God leads people to believe they understand things that they actually are far from understanding; also in The Yale Book of Quotations (2006), ed. Fred R. Shapiro

- When a man after long years of searching chances on a thought which discloses something of the beauty of this mysterious universe, he should not therefore be personally celebrated. He is already sufficiently paid by his experience of seeking and finding. In science, moreover, the work of the individual is so bound up with that of his scientific predecessors and contemporaries that it appears almost as an impersonal product of his generation.

- From the story "The Progress of Science" in The Scientific Monthly edited by J. McKeen Cattell (June 1921), Vol. XII, No. 6. The story says that the comments were made at the annual meeting of the National Academy of Sciences at the National Museum in Washington on April 25, 26, and 27. Einstein's comments appear on p. 579, though the story may be paraphrasing rather than directly quoting since it says "In reply Professor Einstein in substance said" the quote above.

- [I do not] carry such information in my mind since it is readily available in books. ...The value of a college education is not the learning of many facts but the training of the mind to think.

- In response to not knowing the speed of sound as included in the Edison Test: New York Times (18 May 1921); Einstein: His Life and Times (1947) Philipp Frank, p. 185; Einstein, A Life (1996) by Denis Brian, p. 129; "Einstein Due Today" (February 2005) edited by József Illy, Manuscript 25-32 of the Einstein Paper Project; all previous sources as per Einstein His Life and Universe (2007) by Walter Isaacson, p. 299

- Unsourced variants: "I never commit to memory anything that can easily be looked up in a book" and "Never memorize what you can look up in books." (The second version is found in "Recording the Experience" (10 June 2004) at The Library of Congress, but no citation to Einstein's writings is given).

- Insofern sich die Sätze der Mathematik auf die Wirklichkeit beziehen, sind sie nicht sicher, und insofern sie sicher sind, beziehen sie sich nicht auf die Wirklichkeit.

- In so far as theories of mathematics speak about reality, they are not certain, and in so far as they are certain, they do not speak about reality.

- Geometrie and Erfahrung (1921) pp. 3-4 link.springer.com as cited by Karl Popper, The Two Fundamental Problems of the Theory of Knowledge (2014) Tr. Andreas Pickel, Ed. Troels Eggers Hansen.

- I was sitting in a chair in the patent office at Bern when all of sudden a thought occurred to me: If a person falls freely he will not feel his own weight. I was startled. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. It impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.

- Einstein in his Kyoto address (14 December 1922), talking about the events of "probably the 2nd or 3rd weeks" of October 1907, quoted in Why Did Einstein Put So Much Emphasis on the Equivalence Principle? by Dr. Robert J. Heaston in Equivalence Principle – April 2008 (15th NPA Conference) who cites A. Einstein. "How I Constructed the Theory of Relativity," Translated by Masahiro Morikawa from the text recorded in Japanese by Jun Ishiwara, Association of Asia Pacific Physical Societies (AAPPS) Bulletin, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 17-19 (April 2005)

- I have come to believe that the motion of the Earth cannot be detected by any optical experiment.

- How I Created the Theory of Relativity, speech at Kyoto University, Japan, December 14, 1922, as cited in Physics Today, August, 1982.

- May they not forget to keep pure the great heritage that puts them ahead of the West: the artistic configuration of life, the simplicity and modesty of personal needs, and the purity and serenity of the Japanese soul.

- Comment made after a six-week trip to Japan in November-December 1922, published in Kaizo 5, no. 1 (January 1923), 339. Einstein Archive 36-477.1. Appears in The New Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice (2005), p. 269

- Die Quantenmechanik ist sehr achtung-gebietend. Aber eine innere Stimme sagt mir, daß das doch nicht der wahre Jakob ist. Die Theorie liefert viel, aber dem Geheimnis des Alten bringt sie uns kaum näher. Jedenfalls bin ich überzeugt, daß der nicht würfelt.

- Quantum mechanics is certainly imposing. But an inner voice tells me that it is not yet the real thing. The theory says a lot, but does not really bring us any closer to the secret of the "old one." I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice.

- Letter to Max Born (4 December 1926); The Born-Einstein Letters (translated by Irene Born) (Walker and Company, New York, 1971) ISBN 0-8027-0326-7.

- Einstein himself used variants of this quote at other times. For example, in a 1943 conversation with William Hermanns recorded in Hermanns' book Einstein and the Poet, Einstein said: "As I have said so many times, God doesn't play dice with the world." (p. 58)

- Whether you can observe a thing or not depends on the theory which you use. It is the theory which decides what can be observed.

- Objecting to the placing of observables at the heart of the new quantum mechanics, during Heisenberg's 1926 lecture at Berlin; related by Heisenberg, quoted in Unification of Fundamental Forces (1990) by Abdus Salam ISBN 0521371406

- Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature and you will find that, behind all the discernible concatenations, there remains something subtle, intangible and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion. To that extent I am, in point of fact, religious.

- p. 157 London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

- Response to atheist Alfred Kerr in the winter of 1927, who after deriding ideas of God and religion at a dinner party in the home of the publisher Samuel Fischer, had queried him "I hear that you are supposed to be deeply religious" as quoted in The Diary of a Cosmopolitan (1971) by H. G. Kessler

- Ich glaube an Spinoza's Gott, der sich in der gesetzlichen Harmonie des Seienden offenbart, nicht an einen Gott, der sich mit Schicksalen und Handlungen der Menschen abgibt.

- I believe in Spinoza's God, Who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God Who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.

- 24 April 1929 in response to the telegrammed question of New York's Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein: "Do you believe in God? Stop. Answer paid 50 words." Einstein replied in only 27 (German) words. The New York Times 25 April 1929

- Similarly, in a letter to Maurice Solovine, he wrote: "I can understand your aversion to the use of the term 'religion' to describe an emotional and psychological attitude which shows itself most clearly in Spinoza... I have not found a better expression than 'religious' for the trust in the rational nature of reality that is, at least to a certain extent, accessible to human reason."

- As quoted in Einstein : Science and Religion by Arnold V. Lesikar

- If A is success in life, then A = x + y + z. Work is x, play is y and z is keeping your mouth shut.

- Said to Samuel J Woolf, Berlin, Summer 1929. Cited with additional notes in The Ultimate Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice and Freeman Dyson, Princeton UP (2010) p 230

- Science is international but its success is based on institutions, which are owned by nations. If therefore, we wish to promote culture we have to combine and to organize institutions with our own power and means.

- When asked the question, "Why a 'Jewish' University?" when Einstein was assisting Chaim Weizmann in fundraising for The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- As quoted in [Albert Einstein, Letter "Einstein in Singapore." Manchester Guardian, October 12, 1929]

- When asked the question, "Why a 'Jewish' University?" when Einstein was assisting Chaim Weizmann in fundraising for The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Sidelights on Relativity (1922)

- Sidelights on Relativity (1922), translation by GB Jeffrey and W Perrett of "Äther und Relativitätstheorie" (Aether and Relativity Theory), a talk given on 5 May 1920 at the University of Leiden, and "Geometrie und Erfahrung" (Geometry and Experience), a lecture given at the Prussian Academy published in Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1921 (pt. 1), pp. 123–130

- How can it be that mathematics, being, after all, a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality? Is human reason, then, without experience, merely by taking thought, able to fathom the properties of real things?

- One reason why mathematics enjoys special esteem, above all other sciences, is that its laws are absolutely certain and indisputable, while those of other sciences are to some extent debatable and in constant danger of being overthrown by newly discovered facts.

Viereck interview (1929)

- "What Life Means to Einstein: An Interview by George Sylvester Viereck" The Saturday Evening Post (26 October 1929), p. 17. A scan of the article is available online here. A transcription is available here.

- The meaning of relativity has been widely misunderstood. Philosophers play with the word, like a child with a doll. Relativity, as I see it, merely denotes that certain physical and mechanical facts, which have been regarded as positive and permanent, are relative with regard to certain other facts in the sphere of physics and mechanics. It does not mean that everything in life is relative and that we have the right to turn the whole world mischievously topsy-turvy.

- No man can visualize four dimensions, except mathematically ... I think in four dimensions, but only abstractly. The human mind can picture these dimensions no more than it can envisage electricity. Nevertheless, they are no less real than electro-magnetism, the force which controls our universe, within, and by which we have our being.

- Sometimes one pays most for the things one gets for nothing.

- Quoted in The Ultimate Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice (2010), p. 230

- I refuse to make money out of my science. My laurel is not for sale like so many bales of cotton.

- If I was not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music. ... I cannot tell if I would have done any creative work of importance in music, but I do know that I get most joy in life out of my violin.

- Reading after a certain age diverts the mind too much from its creative pursuits. Any man who reads too much and uses his own brain too little falls into lazy habits of thinking, just as the man who spends too much time in the theater is tempted to be content with living vicariously instead of living his own life.

- Our time is Gothic in its spirit. Unlike the Renaissance, it is not dominated by a few outstanding personalities. The twentieth century has established the democracy of the intellect. In the republic of art and science, there are many men who take an equally important part in the intellectual movements of our age. It is the epoch rather than the individual that is important. There is no one dominant personality like Galileo or Newton. Even in the nineteenth century, there were still a few giants who outtopped all others. Today the general level is much higher than ever before in the history of the world, but there are few men whose stature immediately sets them apart from all others.

- In America, more than anywhere else, the individual is lost in the achievements of the many. America is beginning to be the world leader in a scientific investigation. American scholarship is both patient and inspiring. The Americans show an unselfish devotion to science, which is the very opposite of the conventional European view of your countrymen. Too many of us look upon Americans as dollar chasers. This is a cruel libel, even if it is reiterated thoughtlessly by the Americans themselves. It is not true that the dollar is an American fetish. The American student is not interested in dollars, not even in success as such, but in his task, the object of the search. It is his painstaking application to the study of the infinitely little and the infinitely large which accounts for his success in astronomy.

- We are inclined to overemphasize the material influences in history. The Russians especially make this mistake. Intellectual values and ethnic influences, tradition and emotional factors are equally important. If this were not the case, Europe would today be a federated state, not a madhouse of nationalism.

- I am a determinist. As such, I do not believe in free will. The Jews believe in free will. They believe that man shapes his own life. I reject that doctrine philosophically. In that respect, I am not a Jew.

- Quoted in Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson, p. 387

- I believe with Schopenhauer: We can do what we wish, but we can only wish what we must. Practically, I am, nevertheless, compelled to act as if freedom of the will existed. If I wish to live in a civilized community, I must act as if man is a responsible being. I know that philosophically a murderer is not responsible for his crime; nevertheless, I must protect myself from unpleasant contacts. I may consider him guiltless, but I prefer not to take tea with him.

- My own career was undoubtedly determined, not by my own will but by various factors over which I have no control—primarily those mysterious glands in which Nature prepares the very essence of life, our internal secretions.

- Whereas materialistic historians and philosophers neglect psychic realities, Freud is inclined to overstress their importance. I am not a psychologist, but it seems to me fairly evident that physiological factors, especially our endocrines, control our destiny ... I am not able to venture a judgment on so important a phase of modern thought. However, it seems to me that psychoanalysis is not always salutary. It may not always be helpful to delve into the subconscious. The machinery of our legs is controlled by a hundred different muscles. Do you think it would help us to walk if we analyzed our legs and knew exactly which one of the little muscles must be employed in locomotion and the order in which they work? ... I am not prepared to accept all his [Freud's] conclusions, but I consider his work an immensely valuable contribution to the science of human behavior. I think he is even greater as a writer than as a psychologist. Freud's brilliant style is unsurpassed by anyone since Schopenhauer.

- The only progress I can see is progress in the organization. The ordinary human being does not live long enough to draw any substantial benefit from his own experience. And no one, it seems, can benefit by the experiences of others. Being both a father and teacher, I know we can teach our children nothing. We can transmit to them neither our knowledge of life nor of mathematics. Each must learn its lesson anew.

- I believe in intuitions and inspirations. I sometimes feel that I am right. I do not know that I am. When two expeditions of scientists, financed by the Royal Academy, went forth to test my theory of relativity, I was convinced that their conclusions would tally with my hypothesis. I was not surprised when the eclipse of May 29, 1919, confirmed my intuitions. I would have been surprised if I had been wrong.

- I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.

- As a child, I received instruction both in the Bible and in the Talmud. I am a Jew, but I am enthralled by the luminous figure of the Nazarene.

- Jesus is too colossal for the pen of phrasemongers, however artful. No man can dispose of Christianity with a bon mot.

- No one can read the Gospels without feeling the actual presence of Jesus. His personality pulsates in every word. No myth is filled with such life.

- As reported in Einstein — A Life (1996) by Denis Brian, when asked about a clipping from a magazine article reporting his comments on Christianity as taken down by Viereck, Einstein carefully read the clipping and replied, " That is what I believe." .

- It is quite possible to be both. I look upon myself as a man. Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.

- When asked by Viereck if he considered himself to be a German or a Jew. A version with slightly different wording is quoted in Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson (2007), p. 386

- We Jews have been too adaptable. We have been too eager to sacrifice our idiosyncrasies for the sake of social conformity. ... Even in modern civilization, the Jew is most happy if he remains a Jew.

- I do not think that religion is the most important element. We are held together rather by a body of tradition, handed down from father to son, which the child imbibes with his mother's milk. The atmosphere of our infancy predetermines our idiosyncrasies and predilections.

- In response to a question about whether religion is the tie holding the Jews together.

- But to return to the Jewish question. Other groups and nations cultivate their individual traditions. There is no reason why we should sacrifice ours. Standardization robs life of its spice. To deprive every ethnic group of its special traditions is to convert the world into a huge Ford plant. I believe in standardizing automobiles. I do not believe in standardizing human beings. Standardization is a great peril which threatens American culture.

- I am happy because I want nothing from anyone. I do not care about money. Decorations, titles or distinctions mean nothing to me. I do not crave praise. The only thing that gives me pleasure, apart from my work, my violin, and my sailboat, is the appreciation of my fellow workers.

- I claim credit for nothing. Everything is determined, the beginning as well as the end, by forces over which we have no control. It is determined for the insect as well as for the star. Human beings, vegetables or cosmic dust, we all dance to a mysterious tune, intoned in the distance by an invisible player.

- I am not an Atheist. I do not know if I can define myself as a Pantheist. The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. May I not reply with a parable? The human mind, no matter how highly trained, cannot grasp the universe. We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library whose walls are covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues. The child knows that someone must have written those books. It does not know who or how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of the human mind, even the greatest and most cultured, toward God. We see a universe marvelously arranged, obeying certain laws, but we understand the laws only dimly. Our limited minds cannot grasp the mysterious force that sways the constellations. I am fascinated by Spinoza's Pantheism. I admire even more his contributions to modern thought. Spinoza is the greatest of modern philosophers because he is the first philosopher who deals with the soul and the body as one, not as two separate things.

- Did not appear in Saturday Evening Post story, but in Glimpses of the Great (1930) by G. S. Viereck, on p. 373. There have been disputes on the accuracy of this quotation.

- Sometimes misquoted as "I don't think I can call myself a pantheist".

- Variant, from Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson, p. 386: I'm not an atheist. The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written these books. It does not know-how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn't know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws but only dimly understand these laws.

- Variant, from Mieczyslaw Taube's Evolution of Matter and Energy on a Cosmic and Planetary Scale (1985), page 1: "The human mind is not capable of grasping the Universe. We are like a little child entering a huge library. The walls are covered to the ceilings with books in many different tongues. The child knows that someone must have written these books. It does not know who or how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. But the child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books - a mysterious order which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects."

- I am fascinated by Spinoza's pantheism, but I admire even more his contribution to modern thought because he is the first philosopher to deal with the soul and body as one, and not two separate things.

- Did not appear in the Saturday Evening Post story, but quoted in Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson, p. 387, in the section discussing Viereck's interview.

1930s

- Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving.

- Letter to his son Eduard (5 February 1930), as quoted in Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe (2007), p. 367

- I believe that whatever we do or live for has its causality; it is good, however, that we cannot see through to it.

- Interview with Rabindranath Tagore (14 April 1930), published in The Religion of Man (1930) by Rabindranath Tagore, p. 222, and in The Tagore Reader (1971) edited by Amiya Chakravarty

- The really good music, whether of the East or of the West, cannot be analyzed.

- Interview with Rabindranath Tagore (14 April 1930), published in The Religion of Man (1930) by Rabindranath Tagore, p. 222, and in The Tagore Reader (1971) edited by Amiya Chakravarty

- I never think of the future. It comes soon enough.

- Attributed in The Encarta Book of Quotations to an interview on the Belgenland (December 1930), which was the ship on which he arrived in New York that month. According to The Ultimate Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice (2010), p. 18, the quote also appears as "Aphorism, 1945-1946" in the Einstein Archives 36-570. Calaprice speculates that "perhaps it was recalled later and inserted into the archives under the later date." According to a snippet on Google Books, the phrase '"I never think of the future," he said. "It comes soon enough."' appears in The Literary Digest: Volume 107 on p. 29, in an article titled "We May Not 'Get' Relativity, But We Like Einstein" from 27 December 1930. The snippet also discusses the "welcome to Professor Einstein on the Belgenland" in New York

- Besides agreeing with the aims of vegetarianism for aesthetic and moral reasons, it is my view that a vegetarian manner of living by its purely physical effect on the human temperament would most beneficially influence a lot of mankind.

- From a letter to Hermann Huth, Vice-President of the German Vegetarian Federation (27 December 1930). Supposedly published in German magazine Vegetarische Warte, which existed from 1882 to 1935. Einstein Archive 46-756. Quoted in The Ultimate Quotable Einstein by Alice Calaprice (2011), p. 453. ISBN 978-0-691-13817-6

- Die Diktatur bringt den Maulkorb und dieser die Stumpfheit. Wissenschaft kann nur gedeihen in einer Atmosphäre des Freien Wortes.

- A dictatorship means muzzles all round and consequently stultification. Science can flourish only in an atmosphere of free speech.

- "Science and Dictatorship," in Dictatorship on Its Trial, by Eminent Leaders of Modern Thought (1930) - later as Dictatorship on Trial (1931), Otto Forst de Battaglia (1889-1965), ed., Huntley Paterson, trans., introduction by Winston Churchill, George G. Harrap & Co., (Reprinted 1977, Beaufort Books Inc., ISBN 0836916077 ISBN 9780836916072 p. 107. Original text of this "nineteen word essay" appears under the German title, "Wissenschaft und Diktatur" in Prozess der Diktatur (1930), Otto Forst de Battaglia (1889-1965), ed., Amalthea-Verlag, p.108.

- A dictatorship means muzzles all round and consequently stultification. Science can flourish only in an atmosphere of free speech.

- Der Glaube an eine vom wahrnehmenden Subjekt unabhängige Außenwelt liegt aller Naturwissenschaft zugrunde.

- First sentence of "Maxwells Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Auffassung des Physikalisch-Realen". Manuscript at the Hebrew University Jerusalem alberteinstein.info

- The belief in an external world independent of the perceiving subject is the basis of all natural science.

- From "Maxwell's Influence on the Evolution of the Idea of Physical Reality," 1931. Available in Einstein Archives: 65-382

- The scientific organization and comprehensive exposition in accessible form of the Talmud has a twofold importance for us Jews. It is important in the first place that the high cultural values of the Talmud should not be lost to modern minds among the Jewish people nor to science, but should operate further as a living force. In the second place, The Talmud must be made an open book to the world, in order to cut the ground from under certain malevolent attacks, of anti-Semitic origin, which borrow countenance from the obscurity and inaccessibility of certain passages in the Talmud. To support this cultural work would thus mean an important achievement for the Jewish people.

- From a letter by Albert Einstein to Professor Chaim Tchernowitz (31 December 1930) of the Jewish Institute of Religion in New York (Hebrew Union College). Jewish Telegraphic Agency (Jewish Daily Bulletin)

- Why does this magnificent applied science which saves work and makes life easier bring us so little happiness? The simple answer runs: Because we have not yet learned to make sensible use of it. In war it serves that we may poison and mutilate each other. In peace it has made our lives hurried and uncertain. Instead of freeing us in great measure from spiritually exhausting labor, it has made men into slaves of machinery, who for the most part complete their monotonous long day's work with disgust and must continually tremble for their poor rations. ... It is not enough that you should understand about applied science in order that your work may increase man's blessings. Concern for the man himself and his fate must always form the chief interest of all technical endeavours; concern for the great unsolved problems of the organization of labor and the distribution of goods in order that the creations of our mind shall be a blessing and not a curse to mankind. Never forget this in the midst of your diagrams and equations.

- Speech to students at the California Institute of Technology, in "Einstein Sees Lack in Applying Science", The New York Times (16 February 1931)

- I believe in intuition and inspiration. ... At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason. When the eclipse of 1919 confirmed my intuition, I was not in the least surprised. In fact I would have been astonished had it turned out otherwise. Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.

- Cosmic Religion : With Other Opinions and Aphorisms (1931) by Albert Einstein, p. 97; also in Transformation : Arts, Communication, Environment (1950) by Harry Holtzman, p. 138. This may be an edited version of some nearly identical quotes from the 1929 Viereck interview below.

- Everyone sits in the prison of his own ideas; he must burst it open, and that in his youth, and so try to test his ideas on reality.

- Miscellaneous, Cosmic Religion, p. 104 (1931)

- I see a clock, but I cannot envision the clockmaker. The human mind is unable to conceive of the four dimensions, so how can it conceive of a God, before whom a thousand years and a thousand dimensions are as one?

- From Cosmic Religion: with Other Opinions and Aphorisms (1931), Albert Einstein, pub. Covici-Friede. Quoted in The Expanded Quotable Einstein, Princeton University Press; 2nd edition (May 30, 2000); Page 208, ISBN 0691070210

- As an eminent pioneer in the realm of high frequency currents... I congratulate you on the great successes of your life's work.

- Einstein's letter to Nikola Tesla for Tesla's 75th birthday (1931)

- What the inventive genius of mankind has bestowed upon us in the last hundred years could have made human life care free and happy if the development of the organizing power of man had been able to keep step with his technical advances. As it is, the hardly bought achievements of the machine age in the hands of our generation are as dangerous as a razor in the hands of a three-year-old child. The possession of wonderful means of production has not brought freedom-only care and hunger.

- writing for the 1932 Disarmament Conference, included in The Nation 1865-1990: Selections From the Independent Magazine of Politics and Culture (1990)

- Without disarmament there can be no lasting peace. On the contrary, the continuation of military armaments in their present extent will with certainty lead to new catastrophies...For the creation of this public opinion in favor of disarmament every person living shares the responsibility, through ever deed and every word.

- writing for the 1932 Disarmament Conference, included in The Nation 1865-1990: Selections From the Independent Magazine of Politics and Culture (1990)

- Only a life lived for others is a life worthwhile.

- In answer to a question asked by the editors of Youth, a journal of Young Israel of Williamsburg, NY. Quoted in the New York Times (June 20, 1932), p. 17

- Unsourced variant: Only a life in the service of others is worth living.

- It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.

- "On the Method of Theoretical Physics" The Herbert Spencer Lecture, delivered at Oxford (10 June 1933); also published in Philosophy of Science, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1934), pp. 163-169., p. 165. [thanks to Dr. Techie @ www.wordorigins.org and JSTOR] The Philosophy of Science print version is available online here.

- There is a quote attributed to Einstein that may have arisen as a paraphrase of the above quote, commonly given as "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler," "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler", or "Make things as simple as possible, but not simpler." See this article from the Quote Investigator for a discussion of where these later variants may have arisen.

- The original quote is very similar to Occam's razor, which advocates that among all hypotheses compatible with all available observations, the simplest hypothesis is the most plausible one.

- The aphorism "everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler" is normally taken to be a warning against too much simplicity and emphasizes that one cannot simplify things to a point where the hypothesis is no more compatible with all observations. The aphorism does not contradict or extend Occam's razor, but rather stresses that both elements of the razor, simplicity and compatibility with the observations, are essential.

- The earliest known appearance of Einstein's razor is an essay by Roger Sessions in the New York Times (8 January 1950), where Sessions appears to be paraphrasing Einstein: "I also remember a remark of Albert Einstein, which certainly applies to music. He said, in effect, that everything should be as simple as it can be, but not simpler."

- Another early appearance, from Time magazine (14 December 1962): "We try to keep in mind a saying attributed to Einstein—that everything must be made as simple as possible, but not one bit simpler."

- Our experience hitherto justifies us in trusting that nature is the realization of the simplest that is mathematically conceivable. I am convinced that purely mathematical construction enables us to find those concepts and those lawlike connections between them that provide the key to the understanding of natural phenomena. Useful mathematical concepts may well be suggested by experience, but in no way can they be derived from it. Experience naturally remains the sole criterion of the usefulness of a mathematical construction for physics. But the actual creative principle lies in mathematics. Thus, in a certain sense, I take it to be true that pure thought can grasp the real, as the ancients had dreamed.

- from On the Method of Theoretical Physics, p. 183. The Herbert Spencer Lecture, delivered at Oxford (10 June 1933). Quoted in Einstein's Philosophy of Science

- Alternate wording in version of On the Method of Theoretical Physics published in Philosophy of Science, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1934), p. 167: "Our experience up to date justifies us in feeling sure that in Nature is actualized the ideal of mathematical simplicity. It is my conviction that pure mathematical construction enables us to discover the concepts and the laws connecting them which give us the key to the understanding of the phenomena of Nature. Experience can of course guide us in our choice of serviceable mathematical concepts; it cannot possibly be the source from which they are derived; experience of course remains the sole criterion of the serviceability of a mathematical construction for physics, but the truly creative principle resides in mathematics. In a certain sense, therefore, I hold it to be true that pure thought is competent to comprehend the real, as the ancients dreamed."

- There are certain occupations, even in modern society, which entail living in isolation and do not require great physical or intellectual effort. Such occupations as the service of lighthouses and lightships come to mind. Would it not be possible to place young people who wish to think about scientific problems, especially of a mathematical or philosophical nature, in such occupations? Very few young people with such ambitions have, even during the most productive period of their lives, the opportunity to devote themselves undisturbed for any length of time to problems of a scientific nature.

- From a speech "Science and Civilization" in the Royal Albert Hall, London (October 3, 1933). Published as "Europe’s Danger—Europe’s Hope" (1934)

- I never failed in mathematics. Before I was fifteen I had mastered differential and integral calculus.

- Response to being shown a "Ripley's Believe It or Not!" column with the headline "Greatest Living Mathematician Failed in Mathematics" (1935). Quoted in Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson (2007), p. 16

- All of science is nothing more than the refinement of everyday thinking.

- "Physics and Reality" in the Journal of the Franklin Institute Vol. 221, Issue 3 (March 1936)

- Variant translation: "The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of everyday thinking." As it appears in the "Physics and Reality" section of the book "Out of My Later Years" by Albert Einstein (1950)

- It has often been said, and certainly not without justification, that the man of science is a poor philosopher. Why then should it not be the right thing for the physicist to let the philosopher do the philosophizing? Such might indeed be the right thing to do at a time when the physicist believes he has at his disposal a rigid system of fundamental laws which are so well established that waves of doubt can't reach them; but it cannot be right at a time when the very foundations of physics itself have become problematic as they are now. At a time like the present, when experience forces us to seek a newer and more solid foundation, the physicist cannot simply surrender to the philosopher the critical contemplation of theoretical foundations; for he himself knows best and feels more surely where the shoe pinches. In looking for an new foundation, he must try to make clear in his own mind just how far the concepts which he uses are justified, and are necessities.

- "Physics and Reality" in the Journal of the Franklin Institute Vol. 221, Issue 3 (March 1936), Pages 349-382

- One may say "the eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility."

- From the article "Physics and Reality" (March 1936), reprinted in Out of My Later Years (1956). The quotation marks may just indicate that he wants to present this as a new aphorism, but it could possibly indicate that he is paraphrasing or quoting someone else — perhaps Immanuel Kant, since in the next sentence he says "It is one of the great realizations of Immanuel Kant that the setting up of a real external world would be senseless without this comprehensibility."

Other variants: - The eternally incomprehensible thing about the world is its comprehensibility.

- In the endnotes to Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson, note 46 on p. 628 says that "Gerald Holton says that this is more properly translated" as the variant above, citing Holton's essay "What Precisely is Thinking?" on p. 161 of Einstein: A Centenary Volume edited by Anthony Philip French.

- The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is comprehensible.

- This version was given in Einstein: A Biography (1954) by Antonina Vallentin, p. 24, and widely quoted afterwards. Vallentin cites "Physics and Reality" in Journal of the Franklin Institute (March 1936), and is possibly giving a variant translation as with Holton.

- The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is at all comprehensible.

- As quoted in Speaking of Science (2000) by Michael Fripp

- The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility ... The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle.

- As quoted in Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson, p. 462. In the original essay "The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle" appears at the end of the paragraph that follows the paragraph in which "The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility" appears.

- From the article "Physics and Reality" (March 1936), reprinted in Out of My Later Years (1956). The quotation marks may just indicate that he wants to present this as a new aphorism, but it could possibly indicate that he is paraphrasing or quoting someone else — perhaps Immanuel Kant, since in the next sentence he says "It is one of the great realizations of Immanuel Kant that the setting up of a real external world would be senseless without this comprehensibility."

- Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that some spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe, one that is vastly superior to that of man.

- Letter to Phyllis Wright (January 24, 1936), published in Dear Professor Einstein: Albert Einstein's Letters to and from Children (Prometheus Books, 2002), p. 129

- All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree. All these aspirations are directed toward ennobling man's life, lifting it from the sphere of mere physical existence and leading the individual towards freedom. It is no mere chance that our older universities developed from clerical schools. Both churches and universities — insofar as they live up to their true function — serve the ennoblement of the individual. They seek to fulfill this great task by spreading moral and cultural understanding, renouncing the use of brute force.

The essential unity of ecclesiastical and secular institutions was lost during the 19th century, to the point of senseless hostility. Yet there was never any doubt as to the striving for culture. No one doubted the sacredness of the goal. It was the approach that was disputed.- "Moral Decay" (1937); Later published in Out of My Later Years (1950)

- Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world. In our endeavor to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he may never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations. He will never be able to compare his picture with the real mechanism and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison. But he certainly believes that, as his knowledge increases, his picture of reality will become simpler and simpler and will explain a wider and wider range of his sensuous impressions. He may also believe in the existence of the ideal limit of knowledge and that it is approached by the human mind. He may call this ideal limit the objective truth.

- The Evolution of Physics (1938) (co-written with Leopold Infeld)

- Fundamental ideas play the most essential role in forming a physical theory. Books on physics are full of complicated mathematical formulae. But thought and ideas, not formulae, are the beginning of every physical theory. The ideas must later take the mathematical form of a quantitative theory, to make possible the comparison with experiment.

- The Evolution of Physics (1938) (co-written with Leopold Infeld)

- The moral decline we are compelled to witness and the suffering it engenders are so oppressive that one cannot ignore them even for a moment. No matter how deeply one immerses oneself in work, a haunting feeling of inescapable tragedy persists. Still, there are moments when one feels free from one's own identification with human limitations and inadequacies. At such moments, one imagines that one stands on some spot of a small planet, gazing in amazement at the cold yet profoundly moving beauty of the eternal, the unfathomable: life and death flow into one, and there is neither evolution nor destiny; only being.

- Letter to Queen Mother Elisabeth of Belgium (9 January 1939), asking for her help in getting an elderly cousin of his out of Germany and into Belgium. Quoted in Einstein on Peace edited by Otto Nathan and Heinz Norden (1960), p. 282

- The standard bearers have grown weak in the defense of their priceless heritage, and the powers of darkness have been strengthened thereby. Weakness of attitude becomes weakness of character; it becomes lack of power to act with courage proportionate to danger. All this must lead to the destruction of our intellectual life unless the danger summons up strong personalities able to fill the lukewarm and discouraged with new strength and resolution.

- Speech made in honor of Thomas Mann in January 1939, when Mann was given the Einstein Prize by the Jewish Forum. Quoted in Einstein Lived Here by Abraham Pais (1994), p. 214

- Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a man as this one ever in flesh and blood walked upon this Earth.

- Statement on the occasion of Gandhi's 70th birthday (1939) Einstein archive 32-601, published in Out of My Later Years (1950).

- Variant: Generations to come, it may be, will scarcely believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.

- Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future. Certain aspects of the situation seem to call for watchfulness and, if necessary, quick action on the part of the Administration... This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable—though much less certain—that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat or exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove to be too heavy for transportation by air.

- Letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt (August 2, 1939, delivered October 11, 1939); reported in Einstein on Peace, ed. Otto Nathan and Heinz Norden (1960, reprinted 1981), pp. 294–95

Wisehart interview (1930)

- M. K. Wisehart, A Close Look at the World's Greatest Thinker, American Magazine, June 1930. Quotes from the interview appear on pp. 52-53 of The Twelve Powers of Man by Charles Fillmore

- Every man knows that in his work he does best and accomplishes most when he has attained a proficiency that enables him to work intuitively. That is, there are things which we come to know so well that we do not know how we know them. So it seems to me in matters of principle. Perhaps we live best and do things best when we are not too conscious of how and why we do them.

- I do not believe in a God who maliciously or arbitrarily interferes in the personal affairs of mankind. My religion consists of a humble admiration for the vast power which manifests itself in that small part of the universe which our poor, weak minds can grasp!

- Much reading after a certain age diverts the mind from its creative pursuits. Any man who reads too much and uses his own brain too little falls into lazy habits of thinking, just as the man who spends too much time in the theaters is apt to be content with living vicariously instead of living his own life.

- I have only two rules which I regard as principles of conduct. The first is: Have no rules. The second is: Be independent of the opinion of others.

Religion and Science (1930)

- Originally written for the New York Times Magazine (9 November 1930); a version with altered wording appeared in Ideas and Opinions (1954)

- Everything that men do or think concerns the satisfaction of the needs they feel or the escape from pain. This must be kept in mind when we seek to understand spiritual or intellectual movements and the way in which they develop. For feelings and longings are the motive forces of all human striving and productivity—however nobly these latter may display themselves to us.

- Wording in Ideas and Opinions: Everything that the human race has done and thought is concerned with the satisfaction of deeply felt needs and the assuagement of pain. One has to keep this constantly in mind if one wishes to understand spiritual movements and their development. Feeling and longing are the motive force behind all human endeavor and human creation, in however exalted a guise the latter may present themselves to us.

- The longing for guidance, for love and succor, provides the stimulus for the growth of a social or moral conception of God. This is the God of Providence, who protects, decides, rewards and punishes. This is the God who, according to man's widening horizon, loves and provides for the life of the race, or of mankind, or who even loves life itself. He is the comforter in unhappiness and in unsatisfied longing, the protector of the souls of the dead. This is the social or moral idea of God.

- Wording in Ideas and Opinions: The desire for guidance, love, and support prompts men to form the social or moral conception of God. This is the God of Providence, who protects, disposes, rewards, and punishes; the God who, according to the limits of the believer's outlook, loves and cherishes the life of the tribe or of the human race, or even life itself; the comforter in sorrow and unsatisfied longing; he who preserves the souls of the dead. This is the social or moral conception of God.

- It is easy to follow in the sacred writings of the Jewish people the development of the religion of fear into the moral religion, which is carried further in the New Testament. The religions of all civilized peoples, especially those of the Orient, are principally moral religions. An important advance in the life of a people is the transformation of the religion of fear into the moral religion. But one must avoid the prejudice that regards the religions of primitive peoples as pure fear religions and those of the civilized races as pure moral religions. All are mixed forms, though the moral element predominates in the higher levels of social life.

- Wording in Ideas and Opinions: The Jewish scriptures admirably illustrate the development from the religion of fear to moral religion, a development continued in the New Testament. The religions of all civilized peoples, especially the peoples of the Orient, are primarily moral religions. The development from a religion of fear to moral religion is a great step in peoples' lives. And yet, that primitive religions are based entirely on fear and the religions of civilized peoples purely on morality is a prejudice against which we must be on our guard. The truth is that all religions are a varying blend of both types, with this differentiation: that on the higher levels of social life the religion of morality predominates.

- Common to all these types is the anthropomorphic character of the idea of God. Only exceptionally gifted individuals or especially noble communities rise essentially above this level; in these there is found a third level of religious experience, even if it is seldom found in a pure form. I will call it the cosmic religious sense. This is hard to make clear to those who do not experience it, since it does not involve an anthropomorphic idea of God; the individual feels the vanity of human desires and aims, and the nobility and marvelous order which are revealed in nature and in the world of thought. He feels the individual destiny as an imprisonment and seeks to experience the totality of existence as a unity full of significance. Indications of this cosmic religious sense can be found even on earlier levels of development—for example, in the Psalms of David and in the Prophets. The cosmic element is much stronger in Buddhism, as, in particular, Schopenhauer's magnificent essays have shown us. The religious geniuses of all times have been distinguished by this cosmic religious sense, which recognizes neither dogmas nor God made in man's image. Consequently there cannot be a church whose chief doctrines are based on the cosmic religious experience. It comes about, therefore, that we find precisely among the heretics of all ages men who were inspired by this highest religious experience; often they appeared to their contemporaries as atheists, but sometimes also as saints. Viewed from this angle, men like Democritus, Francis of Assisi, and Spinoza are near to one another.

- Wording in Ideas and Opinions: Common to all these types is the anthropomorphic character of their conception of God. In general, only individuals of exceptional endowments, and exceptionally high-minded communities, rise to any considerable extent above this level. But there is a third stage of religious experience which belongs to all of them, even though it is rarely found in a pure form: I shall call it cosmic religious feeling. It is very difficult to elucidate this feeling to anyone who is entirely without it, especially as there is no anthropomorphic conception of God corresponding to it. The individual feels the futility of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveal themselves both in nature and in the world of thought. Individual existence impresses him as a sort of prison and he wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole. The beginnings of cosmic religious feeling already appear at an early stage of development, e.g., in many of the Psalms of David and in some of the Prophets. Buddhism, as we have learned especially from the wonderful writings of Schopenhauer, contains a much stronger element of this. The religious geniuses of all ages have been distinguished by this kind of religious feeling, which knows no dogma and no God conceived in man's image; so that there can be no church whose central teachings are based on it. Hence it is precisely among the heretics of every age that we find men who were filled with this highest kind of religious feeling and were in many cases regarded by their contemporaries as atheists, sometimes also as saints. Looked at in this light, men like Democritus, Francis of Assisi, and Spinoza are closely akin to one another.

- How can this cosmic religious experience be communicated from man to man, if it cannot lead to a definite conception of God or to a theology? It seems to me that the most important function of art and of science is to arouse and keep alive this feeling in those who are receptive.

- Wording in Ideas and Opinions: How can cosmic religious feeling be communicated from one person to another, if it can give rise to no definite notion of a God and no theology? In my view, it is the most important function of art and science to awaken this feeling and keep it alive in those who are receptive to it.

- For any one who is pervaded with the sense of causal law in all that happens, who accepts in real earnest the assumption of causality, the idea of Being who interferes with the sequence of events in the world is absolutely impossible. Neither the religion of fear nor the social-moral religion can have any hold on him. A God who rewards and punishes is for him unthinkable, because man acts in accordance with an inner and outer necessity, and would, in the eyes of God, be as little responsible as an inanimate object is for the movements which it makes. Science, in consequence, has been accused of undermining morals—but wrongly. The ethical behavior of man is better based on sympathy, education and social relationships, and requires no support from religion. Man's plight would, indeed, be sad if he had to be kept in order through fear of punishment and hope of rewards after death.

- Wording in Ideas and Opinions: The man who is thoroughly convinced of the universal operation of the law of causation cannot for a moment entertain the idea of a being who interferes in the course of events — provided, of course, that he takes the hypothesis of causality really seriously. He has no use for the religion of fear and equally little for social or moral religion. A God who rewards and punishes is inconceivable to him for the simple reason that a man's actions are determined by necessity, external and internal, so that in God's eyes he cannot be responsible, any more than an inanimate object is responsible for the motions it undergoes. Science has therefore been charged with undermining morality, but the charge is unjust. A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties and needs; no religious basis is necessary. Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hopes of reward after death.

- It is, therefore, quite natural that the churches have always fought against science and have persecuted its supporters. But, on the other hand, I assert that the cosmic religious experience is the strongest and noblest driving force behind scientific research. No one who does not appreciate the terrific exertions, and, above all, the devotion without which pioneer creations in scientific thought cannot come into being, can judge the strength of the feeling out of which alone such work, turned away as it is from immediate practical life, can grow. What a deep faith in the rationality of the structure of the world and what a longing to understand even a small glimpse of the reason revealed in the world there must have been in Kepler and Newton to enable them to unravel the mechanism of the heavens in long years of lonely work! Any one who only knows scientific research in its practical applications may easily come to a wrong interpretation of the state of mind of the men who, surrounded by skeptical contemporaries, have shown the way to kindred spirits scattered over all countries in all centuries. Only those who have dedicated their lives to similar ends can have a living conception of the inspiration which gave these men the power to remain loyal to their purpose in spite of countless failures. It is the cosmic religious sense which grants this power. A contemporary has rightly said that the only deeply religious people of our largely materialistic age are the earnest men of research.