Timeline of Polish science and technology

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

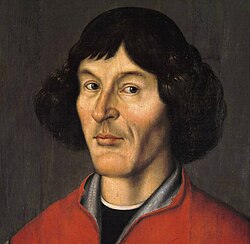

Education has been of prime interest to Poland's rulers since the early 12th century. The catalog of the library of the Cathedral Chapter in Kraków dating from 1110 shows that Polish scholars already then had access to western European literature. In 1364, King Casimir III the Great founded the Cracow Academy, which would become one of the great universities of Europe.[1] The Polish people have made considerable contributions in the fields of science, technology and mathematics.[2] The list of famous scientists in Poland begins in earnest with the polymath, astronomer and mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus, who formulated the heliocentric theory and sparked the European Scientific Revolution.[3]

Polish scientists who played a key role in their disciplines (clockwise): Nicolaus Copernicus, Maria Skłodowska-Curie, Stanisław Ulam, and Benoit Mandelbrot

In 1773, King Stanisław August Poniatowski established the Commission of National Education (Polish: Komisja Edukacji Narodowej, KEN), the world's first ministry of education.[4]

After the third partition of Poland, in 1795, no Polish state existed.[5] The 19th and 20th centuries saw many Polish scientists working abroad. One of them was Maria Skłodowska-Curie, a physicist and chemist living in France. Another noteworthy one was Ignacy Domeyko, a geologist and mineralogist who worked in Chile.[6]

In the first half of the 20th century, Poland was a flourishing center of mathematics. Outstanding Polish mathematicians formed the Lwów School of Mathematics (with Stefan Banach, Hugo Steinhaus, Stanisław Ulam)[7][8] and Warsaw School of Mathematics (with Alfred Tarski, Kazimierz Kuratowski, Wacław Sierpiński). The events of World War II pushed many of them into exile. Such was the case of Benoît Mandelbrot, whose family left Poland when he was still a child. An alumnus of the Warsaw School of Mathematics was Antoni Zygmund, one of the shapers of 20th-century mathematical analysis. According to NASA, Polish scientists were among the pioneers of rocketry.[9]

Today Poland has over 100 institutions of post-secondary education—technical, medical, economic, as well as 500 universities—which are located in most major cities such as Gdańsk, Kraków, Lublin, Łódź, Poznań, Rzeszów, Toruń, Warsaw and Wrocław.[10] They employ over 61,000 scientists and scholars. Another 300 research and development institutes are home to some 10,000 researchers. There are, in addition, a number of smaller laboratories. All together, these institutions support some 91,000 scientists and scholars.

Timeline

From 2001

- Monika Mościbrodzka, Polish astrophysictst known for pioneering the development of numerical astrophysics, which can be used in combination with experimental observations to test general relativity.[11] These studies contributed to the first ever direct image of a black hole, specifically, the supermassive black hole at the centre of Messier 87.[12]

- Olga Malinkiewicz, Polish physicist and inventor of a method of producing solar cells based on perovskites using inkjet printing.[13]

- Lidia Morawska, Polish-Australian physicist whose work focuses on fundamental and applied research in the interdisciplinary field of air quality and its impact on human health, with a specific focus on atmospheric fine, ultrafine and nanoparticles. In 2020, she contributed to the area of airborne infection transmission of viruses, including COVID-19.[14]

- Jarosław Duda, a graduate and employee of Jagiellonian University and inventor of asymmetric numeral systems (ANS), a family of entropy encoding methods widely used in data compression, to encode data e.g. by Facebook Zstandard, Apple LZFSE, CRAM or JPEG XL.[15]

- Poland joins the European Southern Observatory ESO (2014), 16-nation intergovernmental research organisation for astronomy.[16]

- Poland becomes a member the European Space Agency (2012).[17]

- PW-Sat, the first Polish satellite was launched into space (2012); other Polish satellites include Lem and Heweliusz.[18]

- Piorun (missile), a man-portable air-defense system designed to destroy low-flying aircraft, airplanes, helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles.[19]

- AHS Krab, a 155 mm NATO-compatible self-propelled tracked gun-howitzer designed in Poland by Huta Stalowa Wola.[20]

- Polish Artificial Heart Program launched by the Foundation for Cardiac Surgery Development in Zabrze.[21]

- Graphene acquisition, in 2011 the Institute of Electronic Materials Technology and Department of Physics, Warsaw University announced a joint development of acquisition technology of large pieces of graphene with the best quality so far.[22] In April the same year, Polish scientists with support from the Polish Ministry of Economy began the procedure for granting a patent to their discovery around the world.[23]

- Maximal entropy random walk (MERW) is a popular type of biased random walk on a graph, used e.g. in complex network analysis, image analysis, tractography, physics, which was started by article[24] from Jagiellonian University.

- Sylwester Porowski, Polish physicist specializing in solid-state and high pressure physics. In 2001, he led a team of Polish scientists who built a blue semiconductor laser, first blue laser in Poland and third in the world.[25]

- Wojciech H. Zurek, Polish-American theoretical physicist and a leading authority on quantum theory, especially decoherence and non-equilibrium dynamics of symmetry breaking and resulting defect generation; Kibble–Zurek mechanism, Kibble–Zurek scaling laws, quantum discord, einselection,[26] quantum Darwinism, no-cloning theorem.[27]

1951–2000

- Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, Polish-American chemist, discoverer of atom-transfer radical polymerization (1995),[28] a novel method of polymer synthesis that has revolutionized the way macromolecules are made.[29]

- Bohdan Paczyński, Polish astronomer, credited with the development of a new method of detecting space objects and establishing their mass using the gravitational lenses effect;[30][31] he is acknowledged for coining the term microlensing.

- Artur Ekert, Polish physicist; one of the pioneers of quantum cryptography known for quantum entanglement swapping and E91 protocol.[32]

- Janusz Pawliszyn, Polish chemist, inventor of solid-phase microextraction (SPME).[33]

- Andrzej Tarkowski, Polish embryologist and Professor of Warsaw University, known for his pioneering research on embryos and blastomeres, which have created theoretical and practical basis for achievements of biology and medicine of the twentieth century – in vitro fertilization, cloning and stem cell discovery.[34][35]

- Janusz Brzozowski, Polish-Canadian computer scientist known for developing the Brzozowski derivative and Brzozowski's algorithm.[36]

- Aleksander Wolszczan, Polish astronomer who, in 1992, co-discovered the first ever extrasolar planet – PSR 1257+12, a pulsar located 2,630 light years from Earth. It is believed to be orbited by at least four planets.[37]

- Tadeusz Reichstein, Polish-Swiss chemist and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine laureate (1950), who was awarded for his work on the isolation of cortisone.[38]

- Władysław Świątecki, Polish physicist noted for pioneering research in nuclear physics including the nuclear shell model[39] and for independently predicting the existence of the so-called island of stability.[40]

- Jack Tramiel, Polish American businessman, best known for founding Commodore International; Commodore PET, VIC-20 and Commodore 64 are some home computers produced while he was running the company.[41]

- Foundation For Polish Science – a non-governmental organisation aiming at supporting academics with high potential – since (1991)[42]

- Stanisław Kamiński, Polish aeronautical engineer, designer of PZL W-3 Sokół, a helicopter, FAA certificate in (1989)[43]

- Paul Baran, Polish-American engineer who was a pioneer in the development of computer networks; he was one of the two independent inventors of packet switching, which is today the dominant basis for data communications in computer networks worldwide.[44]

- Henryk Magnuski, Polish telecommunications engineer who worked for Motorola in Chicago. He was the inventor of the first Walkie-Talkies and one of the authors of his company success in the fields of radio communication.[45]

- Benoit Mandelbrot, mathematician of Polish descent; known for developing a theory of "roughness and self-similarity" and significant contributions to fractal geometry and chaos theory; Mandelbrot set.[46]

- Flaris LAR01, Polish five-seat single-engined very light jet, currently under development by Metal-Master of Jelenia Góra.[47]

- Solaris Urbino 18 Hybrid, a low-floor articulated hybrid buses from the Solaris Urbino series for city communication services manufactured by Solaris Bus & Coach in Bolechowo near Poznań in Poland.[48]

- PZL Kania, a helicopter, first prototype (1979), FAR-29 certificate (early 1980s).[49]

- Odra (computer), a line of computers manufactured in Wrocław (1959/1960)[50]

- FB MSBS, an assault rifle developed by FB "Łucznik" Radom

- FB Beryl, an assault rifle designed and produced by the Łucznik Arms Factory in the city of Radom

- Polish Polar Station, Hornsund was established in 1957.[51]

- PZL SW-4 Puszczyk, Polish light single-engine multipurpose helicopter manufactured by PZL Swidnik

- EP-09, 'B0B0' Polish electric locomotive class

- PT-91, Polish main battle tank. Designed at the Research and Development Centre of Mechanical Systems OBRUM (Ośrodek Badawczo-Rozwojowy Urządzeń Mechanicznych) in Gliwice

- PZR Grom, an anti-aircraft missile

- 206FM, class minesweeper (NATO: "Krogulec")

- Meteor (rocket), a series of sounding rockets (1963)

- PZL TS-11 Iskra, a jet trainer aircraft, used by the air forces of Poland and India (1960)

- Lim-6, attack aircraft (1955)

- Andrzej Trybulec, Polish mathematician who designed the Mizar system in 1973. The system consists of a formal language for writing mathematical definitions and proofs, a proof assistant, which is able to mechanically check proofs written in this language, and a library of formalized mathematics, which can be used in the proof of new theorems; it was designed by [52]

- Mieczysław G. Bekker, Polish engineer and scientist, co-authored the general idea and contributed significantly to the design and construction of the Lunar Roving Vehicle used by missions Apollo 15, Apollo 16, and Apollo 17 on the Moon.[53]

- The Polish Academy of Sciences, headquartered in Warsaw, was founded in 1951.[54]

- Hilary Koprowski, Polish virologist and immunologist, inventor of the world's first effective live polio vaccine (1950).[55]

- Andrzej Udalski, initiator of the OGLE project, which led to the such significant discoveries as the detection of the first merger of a binary star, first Cepheid pulsating stars in the eclipsing binary systems, unique nova systems, quasars and galaxies.[56]

- Stefania Jabłońska, Polish physician; in 1972 Jabłońska proposed the association of the human papilloma viruses with skin cancer in epidermodysplasia verruciformis; in 1978 Jabłońska and Gerard Orth at the Pasteur Institute discovered HPV-5 in skin cancer; Jabłońska was awarded the 1985 Robert Koch Prize.[57][58]

- Andrew Schally, Polish-American endocrinologist and Nobel Prize laureate (1977).[59] His research contributed to the discovery that the hypothalamus controls hormone production and release by the pituitary gland, which controls the regulation of other hormones in the body.[60]

- Tomasz Dietl, Polish physicist; known for developing the theory, confirmed in recent years, of diluted ferromagnetic semiconductors, and for demonstrating new methods in controlling magnetization.[61]

- Ryszard Horodecki, Polish physicist; he contributed largely to the field of quantum informatics and theoretical physics; Peres-Horodecki criterion.[62]

- Stephanie Kwolek, American chemist of Polish origin, who in 1965 created the first of a family of synthetic fibers of exceptional strength and stiffness. The best-known member is Kevlar, a material used in protective vests as well as in boats, airplanes, ropes, cables, and much more—in total about 200 applications.[63]

- Andrzej Szczeklik, Polish immunologist; credited with discovering the anti-thrombotic properties of aspirin, and studies on the pathogenesis and treatment of aspirin-induced bronchial asthma.[64]

- Antoni Zygmund, Polish mathematician, considered one of the greatest analysts of the 20th century.[65]

- Leonid Hurwicz, Polish economist and mathematician; he originated incentive compatibility and mechanism design, which show how desired outcomes are achieved in economics, social science and political science. In 2007, he shared the Nobel Prize in Economics.[66]

- Jacek Pałkiewicz, Polish journalist, traveler and explorer; fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, discoverer of the sources of the Amazon River (1996).[67]

- Kazimierz Kuratowski, Polish mathematician, a leading representatives of the Warsaw School of Mathematics; Kuratowski's theorem, Kuratowski-Zorn lemma; Kuratowski closure axioms.[68][69]

- Tadek Marek, Polish automobile engineer, known for his Aston Martin engines.[70]

- Otto Marcin Nikodym, Polish mathematician; Radon-Nikodym theorem, Nikodym set, Radon-Nikodym property.[71]

- Zygmunt Bauman, Polish sociologist and philosopher; one of the world's most eminent social theorists writing on issues as diverse as modernity and the Holocaust, postmodern consumerism as well as the concept of liquid modernity which he introduced.[72]

- Kazimierz Dąbrowski, Polish psychologist; he developed the theory of positive disintegration, which describes how a person's development grows as a result of accumulated experiences (1929).[73]

- Jerzy Pniewski and Marian Danysz, Polish physicists discovered hypernucleus in 1952.[74]

- Anna Wierzbicka, Polish linguist; known for her work in semantics, pragmatics and cross-cultural linguistics; she's credited with formulating the theory of natural semantic metalanguage and the concept of semantic primes.[75]

- Michał Misiurewicz, Polish mathematician known for his contributions to chaotic dynamical systems and fractal geometry, notably the Misiurewicz point.[76]

- Andrzej Grzegorczyk, Polish mathematician; he introduced the Grzegorczyk hierarchy – a subrecursive hierarchy that foreshadowed computational complexity theory.

- Stanisław Jaśkowski, Polish mathematician; he is regarded as one of the founders of natural deduction, which he discovered independently of Gerhard Gentzen in the 1930s; he was among the first to propose a formal calculus of inconsistency-tolerant (or paraconsistent) logic; furthermore, Jaśkowski was a pioneer in the investigation of both intuitionistic logic and free logic.[77][78]

- Karol Borsuk, Polish mathematician; his main area of interest was topology; he introduced the theory of absolute retracts (ARs) and absolute neighborhood retracts (ANRs), and the cohomotopy groups, later called Borsuk–Spanier cohomotopy groups; he also founded shape theory; Borsuk's conjecture, Borsuk-Ulam theorem.[79][80]

- Jerzy Konorski, Polish neurophysiologist; he discovered secondary conditioned reflexes and operant conditioning and proposed the idea of gnostic neurons – a concept similar to the grandmother cell; he also coined the term neural plasticity, and he developed theoretical ideas regarding it.[81]

- Antoni Kępiński, Polish psychiatrist; he developed the psychological theory of information metabolism which explores human social interactions based on information processing which significantly influenced the development of socionics.[82]

- Zbigniew Religa, Polish cardiac surgeon; a pioneer in human heart transplantation; in 1987 he performed the first successful heart transplant in Poland;[83] in 1995 he was the first surgeon to graft an artificial valve created from materials taken from human corpses; in 2004 Religa and his team developed an implantable pump for a pneumatic heart assistance system.

- Maria Siemionow, a renowned Polish transplantation surgeon and scientist who gained world recognition when she led a team of eight surgeons through the world's first near-total face transplant at the Cleveland Clinic in 2008.[84]

- Tadeusz Krwawicz, Polish ophthalmologist; he pioneered the use of cryosurgery in ophthalmology;[85] he was the first to describe a method of cataract extraction by cryoadhesion in 1961,[86] and to develop a probe by means of which cataracts can be grasped and extracted.

- Albert Sabin, Polish-American medical researcher, best known for developing the oral polio vaccine which has played a key role in nearly eradicating the disease.[87]

- Jacek Karpiński, Polish pioneer in computer engineering and computer science. He became a developer of one of the first machine learning algorithms, techniques for character and image recognition. In 1971, he designed one of the first minicomputers, the K-202.[88]

- Stefan Kudelski, Polish audio engineer known for creating the Nagra series of professional audio recorders.[89]

- Zdzisław Pawlak, Polish mathematician and computer scientist; known for his contribution to many branches of theoretical computer science; he is credited with introducing the rough set theory and also known for his fundamental works on it; he had also introduced the Pawlak flow graphs, a graphical framework for reasoning from data.[90]

- Samuel Eilenberg, Polish-American mathematician, Eilenberg–MacLane space, Eilenberg–Mazur swindle, Eilenberg–Maclane spectrum, Eilenberg–Steenrod axioms.[91][92]

- Jan Czekanowski, Polish anthropologist, ethnographer, statistician and linguist; one of the founders of computational linguistics,[93] he introduced the Czekanowski binary index.

- Henryk Iwaniec, mathematician, he is noted for his outstanding contributions to analytic number theory and sieve theory; Friedlander-Iwaniec theorem.[94]

- Andrzej Piotr Ruszczyński, Polish-American applied mathematician, noted for his contributions to mathematical optimization, in particular, stochastic programming and risk-averse optimization. He developed the theory of stochastic dominance constraints and created the theory of Markov risk measures.[95]

- Kazimierz Kordylewski, Polish astronomer credited for the discovery of the Kordylewski clouds, large transient concentrations of dust at the Trojan points of the Earth–Moon system, which were reported to have been confirmed to exist in October 2018.[96]

- Andrzej Trautman, Polish mathematical physicist who has made contributions to classical gravitation in general and to general relativity in particular. The "Trautman-Bondi mass" is named after him.[97] Trautman and Ivor Robinson also discovered a family of exact solutions of the Einstein field equation, the Robinson-Trautman gravitational waves.[98]

- Osman Achmatowicz Jr., Polish chemist. He is credited with discovering the Achmatowicz reaction (1971).[99]

- Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, Polish paleobiologist. In the mid-1960s, she led a series of Polish-Mongolian paleontological expeditions to the Gobi Desert. She discovered such dinosaur species as Deinocheirus and Gallimimus.[100][101]

- Jerzy Vetulani, Polish neuroscientist and biochemist. He is known for his early hypothesis of the mechanism of action of antidepressant drugs, suggesting in 1975 together with Fridolin Sulser that downregulation of beta-adrenergic receptors is responsible for their effects.[102][103]

- Zbyszek Darzynkiewicz, Polish-American cell biologist active in cancer research and in developing new methods in histochemistry for flow cytometry.[104]

- Ludwik Gross, Polish-American virologist. He discovered two different tumor viruses—murine leukemia virus and mouse polyomavirus—capable of causing cancers in laboratory mice.[105]

- Ryszard Gryglewski, Polish physician and pharmacologist. He co-discovered prostacyclin (1976), which set off many further scientific discoveries.[106]

- Wacław Szybalski, Polish-American medical researcher, geneticist and oncologist. He conducted research on drug resistance and molecular genetics and is known for the Szybalski's rule.[107][108]

- Bogdan Baranowski, Polish chemist who made notable contributions to the study of non-equilibrium thermodynamics and solid state physical chemistry. He discovered nickel hydride in 1958.[109]

1901–1950

- Józef Kosacki, a Polish Lieutenant who developed the Polish mine detector during World War II (1941–42), a metal detector used for detecting land mines. It contributed substantially to British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's 1942 victory over German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel at El Alamein.[110]

- Marian Rejewski, Polish mathematician who was among the team of Polish cryptologists who broke the Enigma machine in the 1930s. In 1938, he designed the Cryptologic bomb, a special-purpose machine to speed the breaking of the Enigma machine ciphers that would be used by Nazi Germany in World War II. It was a forerunner of the "Bombes" that would be used by the British at Bletchley Park, and which would be a major element in the Allied Ultra program that may have decided the outcome of World War II.[111][112]

- Biuro Szyfrów (Cipher Bureau) was the Polish military intelligence agency that made the first break (1932, just as Adolf Hitler was about to take power in Germany) into the German Enigma machine cipher that would be used by Nazi Germany through World War II, and kept reading Enigma ciphers at least until France's capitulation in June 1940.

- Jan Czochralski, Polish chemist credited with inventing the Czochralski method, a technique of crystal growth used to obtain single crystals of semiconductors (e.g. silicon, germanium and gallium arsenide), metals (e.g. palladium, platinum, silver, gold) and salts (1916). The method is still used in over 90 percent of all electronics in the world that use semiconductors.[113]

- Joseph Rotblat, Polish physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, Nobel laureate.[114]

- Stanisław Ulam, Polish-American mathematician who participated in Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of cellular automaton, invented the Monte Carlo methods of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion.[115][116]

- Wacław Struszyński, a Polish electronics engineer who made a vital contribution to the defeat of U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic, he designed a radio antenna which enabled effective high frequency (HF) radio direction finding systems to be installed on Royal Navy convoy escort ships. Such direction finding systems were referred to as HF/DF or Huff-Duff, and enabled the bearings of U-boats to be determined when the U-boats made high frequency radio transmissions.[117]

- Rudolf Gundlach, Polish engineer who designed the Vickers Tank Periscope MK.IV, the first device to allow the tank commander to have a 360-degree view from his turret (1936).[118][119]

- Jan Łukasiewicz, Polish mathematician and logician who invented the Polish notation, also known as prefix notation, is a method of mathematical expression (1920).[120]

- Reverse Polish notation, (RPN), also known as postfix notation (1920)

- Henryk Zygalski, Polish mathematician who in 1938 invented the Zygalski sheets, also known as "perforated sheets", one of a number of devices created by the Polish Cipher Bureau to facilitate the breaking of German Enigma ciphers.[121]

- Stefan Banach, Polish mathematician who is considered the founder of modern functional analysis.[122] He is known for Banach space, Banach–Tarski paradox, Banach algebra, Functional analysis, Banach fixed-point theorem, uniform boundedness principle, Banach–Alaoglu theorem and Banach measure.

- Lwów School of Mathematics was a group of eminent Polish mathematicians that included Hugo Steinhaus, Stanisław Ulam, Mark Kac and many more.[123]

- Stefan Kaczmarz, Polish mathematician known for the Kaczmarz method, which provided the basis for many modern imaging technologies, including the CAT scan.[124]

- Tadeusz Banachiewicz, Polish astronomer, inventor of the chronocinematograph (1927).[125][126]

- 7TP, light tank of the Second World War (1935).

- Piotr Wilniewczyc, Polish engineer and arms designer. He designed FB Vis, a 9×19mm caliber, single-action, semi-automatic pistol.

- PZL.23 Karaś, light bomber and reconnaissance aircraft designed in the PZL (1934)

- Zygmunt Pulawski, Polish aircraft designer. He designed in the early 1930s PZL P.11, Polish fighter aircraft. It was briefly the most advanced fighter aircraft of its kind in the world.

- Jerzy Dąbrowski, Polish aeronautical engineer. He designed in the mid-1930s PZL.37 Łoś, twin-engine medium bomber.[127]

- Zbysław Ciołkosz, Polish aircraft designer who designed LWS-6 Żubr, initially a passenger plane. Since the Polish airline LOT bought Douglas DC-2 planes instead, the project was converted to a bomber aircraft (early-1930s).

- SS Sołdek, the first ship built in Poland after World War II (1948)

- Alfred Korzybski, Polish philosopher and mathematician who developed the field of general semantics and is known for the map–territory relation.[128]

- Mieczysław Wolfke, Polish physicist considered "one of precursors in the development of holography" (a quote from Dennis Gabor).[129]

- Hugo Steinhaus, Polish mathematician; one of the founders of the Lwów School of Mathematics, he is regarded as one of the early founders of game theory and probability theory which led to later development of more comprehensive approaches by other scholars; Banach-Steinhaus theorem, three-gap theorem.[130]

- LWS, an abbreviation name used by Polish aircraft manufacturer Lubelska Wytwórnia Samolotów (1936–1939)

- PZL, an abbreviation name used by Polish aerospace manufacturers (1928–present)

- RWD, an abbreviation name used by Polish aircraft manufacturer (1920–1940)

- TKS, a tankette (1931)

- Stefan Tyszkiewicz, Polish engineer and inventor. He founded automobile manufacturing company Stetysz (1929).

- RWD-1, sports plane of 1928, constructed by the RWD

- Józef Maroszek, Polish arms designer. He designed Wz. 35 anti-tank rifle, Polish 7.9 mm anti-tank rifle used by the Polish Army during the Invasion of Poland of 1939.

- Marian Smoluchowski, Polish scientist, pioneer of statistical physics – Einstein–Smoluchowski relation, Smoluchowski coagulation equation, Feynman-Smoluchowski ratchet.[131]

- Kazimierz Fajans, Polish physical chemist, the co-discoverer of chemical element protactinium (1913).[132] He is also known for the Fajans' rules, Fajan's and Soddy's law, Fajans–Paneth–Hahn Law and Fajans method.[133]

- Kazimierz Funk, Polish biochemist, credited with formulating the concept of vitamines.[134][135]

- Alfred Tarski, a renowned Polish logician, mathematician and philosopher; Banach–Tarski paradox, Tarski's axioms, Tarski's undefinability theorem, semantic theory of truth, Tarski monster group, Jónsson–Tarski duality.[136][137]

- Wacław Sierpiński, known for outstanding contributions to set theory (research on the axiom of choice and the continuum hypothesis), number theory, theory of functions and topology; Sierpiński triangle, Sierpiński carpet, Sierpiński curve, Sierpiński number.[138][139]

- Wiktor Kemula, Polish chemist. He developed the hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE).

- Aleksander Jabłoński, Polish physicist, known for Jablonski diagram.[140]

- Maksymilian Faktorowicz, also known as Max Factor Sr., Polish-American businessman, beautician, entrepreneur and inventor. As a founder of the cosmetics giant Max Factor & Company, he largely developed the modern cosmetics industry in the United States.[141]

- Franciszek Mertens, mathematician known for Mertens function, Mertens conjecture, Mertens's theorems.[142]

- Josef Hofmann, designer of first windscreen wipers.[143]

- Rudolf Weigl, Polish biologist and inventor of the first effective vaccine against epidemic typhus.[144]

- Ludwik Hirszfeld, Polish microbiologist and serologist. He is considered a co-discoverer of the inheritance of ABO blood types.[145]

- Michał Kalecki, Polish economist; he has been called "one of the most distinguished economists of the 20th century",[146] he made major theoretical and practical contributions in the areas of the business cycle, growth, full employment, income distribution, the political boom cycle, the oligopolistic economy, and risk; he offered a synthesis that integrated Marxist class analysis and the then-new literature on oligopoly theory, and his work had a significant influence on both the Neo-Marxian and Post-Keynesian schools of economic thought; he was also one of the first macroeconomists to apply mathematical models and statistical data to economic questions.

- Stefan Bryła, Polish construction engineer and welding pioneer; he designed and built the first welded road bridge in the world as well as the Prudential building in Warsaw, one of the first European skyscrapers.[147][148]

- Kazimierz Zarankiewicz, Polish mathematician who was primarily interested in topology and graph theory known for Zarankiewicz problem and Zarankiewicz crossing number conjecture.

- Juliusz Schauder, Polish mathematician known for Schauder basis, Schauder fixed-point theorem, Schauder estimates, Banach–Schauder theorem and Faber-Schauder system.

- Ralph Modjeski, Polish civil engineer who achieved prominence as a pre-eminent bridge designer in the United States.[149][150]

- Wojciech Świętosławski, Polish chemist and physicist, considered the father of thermochemistry

- Józef Tykociński, Polish engineer and a pioneer of sound-on-film technology

- Mieczysław Mąkosza, Polish chemist specializing in organic synthesis and investigation of organic mechanisms; he is credited for the discovery of the aromatic vicarious nucleophilic substitution, VNS; he also contributed to the discovery of phase transfer catalysis reactions.[151]

- Bronisław Malinowski, Polish anthropologist, often considered one of the most important 20th-century anthropologists. His writings on ethnography, social theory, and field research have exerted a profound influence on the discipline of anthropology.[152]

- Mirosław Hermaszewski, Polish Air Force officer and cosmonaut; the first Polish person in space.[153]

- Henryk Arctowski, Polish scientist, explorer and an internationally renowned meteorologist; a pioneer in the exploration of Antarctica.[154][155]

- Stefan Drzewiecki, Polish engineer and inventor who constructed the world's first electric submarine in 1884.[156] He developed several models of propeller-driven submarines that evolved from single-person vessels to a four-man model; he developed the blade element theory (1885), the theory of gliding flight, developed a method for the manufacture of ship and plane propellers (1892), and presented a general theory for screw-propeller thrust (1920); he also developed several models of early submarines for the Russian Navy, and devised a torpedo-launching system for ships and submarines that bears his name, the Drzewiecki drop collar; he also made an instrument that drew the precise routes of ships onto a nautical chart; his work Theorie générale de l'hélice (1920), was honored by the French Academy of Sciences as fundamental in the development of modern propellers.

- Tadeusz Tański, Polish automobile engineer and the designer of, among others, the first Polish serially-built automobile, the CWS T-1

- Leonard Danilewicz, Polish engineer, he came up with a concept for a frequency-hopping spread spectrum.[157]

- Florian Znaniecki, Polish sociologist and philosopher; he made significant contributions to sociological theory and introduced such concepts as humanistic coefficient and culturalism; he is the co-author of The Polish Peasant in Europe and America, which is considered the foundation of modern empirical sociology.[158]

- Adolf Beck, Polish physiologist, a pioneer of electroencephalography (EEG); in 1890 he published an investigation of spontaneous electrical activity of the brain of rabbits and dogs that included rhythmic oscillations altered by light; Beck started experiments on the electrical brain activity of animals; his observation of fluctuating brain activity led to the conclusion of brain waves.[159]

- Andrzej Schinzel, Polish mathematician, studying mainly number theory; Schinzel's hypothesis H, Davenport–Schinzel sequence

- Władysław Starewicz, Polish-Russian pioneering film director and stop-motion animator, he is notable as the author of the first puppet-animated film i.e. The Beautiful Lukanida (1912).[160]

- Witold Hurewicz, Polish mathematician; Hurewicz space, Hurewicz theorem.[161]

- Józef Wierusz-Kowalski, Polish physicist, discoverer of the phenomenon of progressive phosphorescence.[162]

- Henryk Derczyński, Polish photographer. He developed the isohelia technology, a technique that sharpens contrasts and defines three-dimensional images.[163]

- Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Russian and Soviet rocket scientist of Polish descent. He pioneered astronautics and is considered one of the pioneers of space flight and the founding father of modern rocketry and astronautics.[164][165]

- Tadeusz Sendzimir, Polish engineer and inventor with 120 patents in mining and metallurgy.[166] He developed revolutionary methods of processing steel and metals and is known for the Sendzimir mill and Sendzimir process.[167]

- Jerzy Rudlicki, Polish aerospace engineer and pilot. He is best known for his inventing and patenting of the V-tail in 1930, which is an aircraft tail configuration that combines the rudder and elevators into one system.[168]

- Leopold Infeld, Polish physicist known for Born–Infeld model, Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations and Infeld–Van der Waerden symbols.[169]

- Eugène Minkowski, Polish psychiatrist and emigrant to France, known for his incorporation of phenomenology into psychopathology.[170]

- Frank Piasecki, American engineer of Polish descent known as a helicopter aviation pioneer. He pioneered tandem rotor helicopter designs and created the compound helicopter concept of vectored thrust using a ducted propeller.[171]

- Władysław Świątecki, Polish airman and inventor known for the Swiatecki bomb slip.

- Jakub Karol Parnas, Polish-Soviet biochemist. He co-discovered the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway, the most common type of glycolysis,[172] and phosphorolysis.[173]

- Joseph Szydlowski, Polish-Israeli aircraft engine designer who founded Turbomeca in France.

- Józef Lubański, Polish theoretical physicist. He developed the Pauli–Lubanski pseudovector in relativistic quantum mechanics.[174]

1851–1900

- Maria Skłodowska-Curie, Polish chemist and physicist, a pioneer in the field of radioactivity, co-discoverer of the chemical elements radium and polonium.[175]

- Zygmunt Wróblewski and Karol Olszewski, the first to liquefy oxygen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in a stable state (not, as had been the case up to then, in a dynamic state in the transitional form as vapour) (1833).[176]

- Zygmunt Florenty Wróblewski discovers carbon dioxide clathrate (1882).[177]

- Ignacy Łukasiewicz, Polish pharmacist and petroleum industry pioneer who in 1856 built the world's first oil refinery; his achievements included the discovery of how to distill kerosene from seep oil, the invention of the modern kerosene lamp, the introduction of the first modern street lamp in Europe, and the construction one of the world's first modern oil well.[178][179]

- The Polish Academy of Learning, an academy of sciences, was founded in Kraków in 1872.

- Casimir Zeglen, inventor of one of the first bulletproof vests.[180][181]

- Józef Paczoski, Polish botanist; he coined the term of phytosociology and was one of the founders of this branch of botany (1896).[182]

- Jan Szczepanik, Polish inventor, with several hundred patents and over 50 discoveries to his name, many of which are still applied today, especially in the motion picture industry, as well as in photography and television, which include telectroscope and colorimeter.[183]

- Edmund Biernacki, Polish pathologist, known for the Biernacki reaction used worldwide to assess erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), which is one of the major blood tests.[184]

- Ludwik Gumplowicz, Polish sociologist, "one of the forerunners of scientific sociology".[185]

- Antoni Leśniowski, Polish surgeon, discoverer of Leśniowski-Crohn's disease.[186]

- Edward Flatau, Polish neurologist and psychiatrist, his name in medicine is linked to Redlich-Flatau syndrome, Flatau-Sterling torsion dystonia, Flatau-Schidler disease and Flatau's law. He published a human brain atlas (1894), wrote a fundamental book on migraine (1912), established the localization principle of long fibers in the spinal cord (1893), and with Sterling published an early paper (1911) on progressive torsion spasm in children and suggested that the disease has a genetic component.

- Kazimierz Prószyński, Polish inventor active in the field of cinema; he patented his first film camera, called Pleograph, before the Lumière brothers, and later went on to improve the cinema projector for the Gaumont company, as well as invent the widely used hand-held Aeroscope camera.[187]

- Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky, Polish-Russian engineer and electrician; inventor of the three-phase electric power system. In 1891, he also created a three-phase transformer and short-circuited (squirrel-cage) induction motor.[188][189]

- Joseph Babinski, a neurologist best known for his 1896 description of the Babinski sign, a pathological plantar reflex indicative of corticospinal tract damage.[190]

- Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, a Polish linguist, he formulated the theory of the phoneme and phonetic alternations.[191]

- Ernest Malinowski, Polish engineer, he constructed at that time the world's highest railway Ferrocarril Central Andino in the Peruvian Andes in 1871–1876.[192][193]

- Bruno Abakanowicz, Polish mathematician and electrical engineer, inventor of the integraph,[194] spirograph, parabolagraph and an electric arc lamp of his own design.[195]

- Stanisław Kierbedź, Polish-Russian engineer, and military officer; he constructed the first permanent iron bridge over the Vistula River in Warsaw known as the Kierbedź Bridge; he designed and supervised the construction of dozens of bridges, railway lines, ports and other objects in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Felicjan Sypniewski, Polish naturalist, botanist, entomologist and philosopher; his ground-breaking studies and scientific publications laid down the foundations of malacology

- L.L. Zamenhof, Polish medical doctor, inventor and writer; creator of Esperanto, the most successful constructed language in the world.[196]

- Napoleon Cybulski, Polish physiologist and a pioneer of endocrinology and electroencephalography; discoverer of adrenaline (1895).[197]

- Wacław Mayzel, Polish histologist; he described for the first time the process of mitosis in animal cells.[198][199]

- Antoni Patek, Polish pioneer in watchmaking and a creator of Patek Philippe & Co., one of the most famous watchmaker companies in the world.[200]

- Ludwik Rydygier, Polish surgeon; in 1880, as the first in Poland and second in the world he succeeded in surgical removal of the pylorus in a patient suffering from stomach cancer,[201] he was also the first to document this procedure; in 1881, as the first in the world, he carried out a peptic ulcer resection; in 1884 he introduced a new method of surgical peptic ulcer treatment using Gastroenterostomy; Rydygier proposed (1900) original concepts for removing prostatic adenoma and introduced many other surgical techniques that are successfully used to date.[202]

- Jan Dzierżoń, a pioneering Polish apiarist who discovered the phenomenon of parthenogenesis in bees[203] and designed the first successful movable-frame beehive (1838);[204] his discoveries and innovations made him world-famous in scientific and bee-keeping circles; he has been described as "the father of apiculture".

- Stanisław Leśniewski, philosopher and logician, known for coining the term mereology.[205]

- Stanisław Kostanecki, Polish chemist known for the Kostanecki acylation.[206]

- Marceli Nencki, Polish chemist. He demonstrated that urea is formed in the organism from amino acids rather than being preformed on a protein molecule and that it is accompanied by binding of carbon dioxide. He also discovered rhodanine in 1877.[207]

- Bohdan Szyszkowski, Polish chemist and member of Polish Academy of Learning. He published important papers on electrochemistry and surface chemistry and is known for the Szyszkowski equation.[208]

- Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, Polish-German pioneering surgeon. He was the inventor of new operating techniques and tools, and is one of the pioneers of antiseptics and aseptic techniques. He created a surgical mask[209] and was the first to use medical gloves during surgery. He is known for Mikulicz' disease, Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty, Mikulicz's drain.

- Aleksander Możajski, Polish-Russian aviation pioneer, researcher and designer of Mozhaysky's airplane.[210][211]

- Stanisław Olszewski, Polish engineer and inventor. He is best known as the co-creator of the technology of arc welding (along with Nikolay Benardos).[212]

- Karol Adamiecki, Polish engineer and management theorist. He invented a novel means of displaying interdependent processes so as to enhance the visibility of production schedules (1896). With minor modifications, Adamiecki's chart is now more commonly referred to in English as the Gantt chart.[213]

- Walery Jaworski, one of the pioneers of gastroenterology in Poland; he described bacteria living in the human stomach and speculated that they were responsible for stomach ulcers, gastric cancer and achylia. It was one of the first observations of Helicobacter pylori. He published those findings in 1899 in a book titled "Podręcznik chorób żołądka" ("Handbook of Gastric Diseases"). His findings were independently confirmed by Robin Warren and Barry Marshall, who received the Nobel Prize in 2005.[214]

- Albert Wojciech Adamkiewicz, Polish pathologist. His research of the variable vascularity of the spinal cord was an important contribution to the development of modern clinical vascular surgery. He is known for Artery of Adamkiewicz and Adamkiewicz reaction.[215]

- Justyn Karliński, physician and epidemiologist, who discovered over 20 bacteria in Bosnian waters. The discovery enabled the development of vaccines for numerous infectious diseases of humans and animals.[216]

- Adam Bruno Wikszemski, inventor of a device for phonographic recording of sound vibrations (1889)[217]

- Ivan Yarkovsky, Polish-Russian civil engineer. He is credited with the discovery of the Yarkovsky effect and the co-discovery the YORP effect.[218]

1801–1850

- Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński, Polish philosopher, mathematician, physicist, inventor, lawyer, occultist and economist. In mathematics, he is known for introducing a novel series expansion for a function in response to Joseph Louis Lagrange's use of infinite series. The coefficients in Wroński's new series form the Wronskian. He is also known for designing continuous track.[219]

- Felix Wierzbicki, physician and geographer, author of California as It Is and as It May Be, or A Guide to the Gold Region, the first English-language geographic overview and guide to California (1849)[220]

- Ignacy Domeyko – geologist and mineralogist, a geological map of Chile, describing the Jurassic rock formations, and discovered deposits of a rare mineral (1846).[221]

- Paweł Strzelecki, Polish explorer and geologist; in 1840 he climbed the highest peak on mainland Australia and named it Mount Kosciuszko; he made a geological and mineralogical survey of the Gippsland region in present-day eastern Victoria and from 1840 to 1842 he explored nearly every part of Tasmania; author of Physical Description of New South Wales (1845).[222][223][224]

- Jędrzej Śniadecki, Polish writer, physician, chemist, biologist and philosopher. He became the first person who linked rickets to lack of sunlight (1822). He also created modern Polish terminology in the field of chemistry.[225][226][227]

- Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Polish scholar, poet, and statesman

- Ignacy Prądzyński, Polish military commander and general; principal engineer and designer of the Augustów Canal

- Wojciech Jastrzębowski, Polish scientist, naturalist and inventor, professor of botany, physics, zoology and horticulture; considered as one of the fathers of ergonomics

- Alexander I established the University of Warsaw (1816) on the initiative of Stanisław Potocki and Stanisław Staszic.[228]

1701–1800

- Commission of National Education (Polish: Komisja Edukacji Narodowej), founded in 1773, was the world's first national Ministry of Education.

- Stanisław Staszic was an outstanding Polish philosopher, statesman, Catholic priest, geologist, translator, poet and writer—almost a one-man academy of sciences. The Polish Academy of Sciences' Staszic Palace, in Warsaw, is named after him; one of the founding fathers of the Constitution of May 3, 1791—the world's second and Europe's first written constitution and a crowning achievement of the Polish Enlightenment

- Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński, Polish Messianist philosopher, mathematician, physicist, inventor, lawyer, and economist; he is credited with formulating the Wronskian and developing the system of continuous track.[229]

1601–1700

- Adam Adamandy Kochański, Polish mathematician, physicist and clockmaker found an approximation of π today called the Kochański's Approximation (1685).[230] He also suggested replacing the clock's pendulum with a spring (1659), constructed a clock with a magnetic pendulum (1667), and was the author of the world's first systematic paper on the construction of clocks.

- Johannes Hevelius was an astronomer who published the earliest exact maps of the moon and the most complete star catalog of his time, containing 1,564 stars. In 1641 he built an observatory in his house; he is known as "the founder of lunar topography".[231]

- Jan Brożek (Ioannes Broscius) was the most prominent 17th-century Polish mathematician. Following his death, his collection of Nicolaus Copernicus' letters and documents, which he had borrowed 40 years earlier with the intent of writing a biography of Copernicus, was lost.

- Kazimierz Siemienowicz, Polish–Lithuanian general of artillery, gunsmith, military engineer, and pioneer of rocketry who developed the concept of a multistage rocket.

- King of Poland, John II Casimir, founded the University of Lviv (1661).[232]

- Michał Boym, Polish Jesuit missionary to China, scientist and explorer; he is notable as one of the first westerners to travel within the Chinese mainland, and the author of numerous works on Asian fauna, flora and geography. He was the first in Europe to describe Korea as a peninsula, as until then it was believed to be an island, and the first in Europe to establish the factual location of a number of Chinese cities and the Great Wall of China.[233]

- Adam Freytag, mathematician and military engineer, wrote Architectura militaris nova et aucta, the first manual of bastion fortifications of the so-called Old Dutch system (1631).

- Krzysztof Arciszewski, Polish–Lithuanian nobleman, military officer, engineer, and ethnographer. Arciszewski also served as a general of artillery for the Netherlands and Poland

- Adam Wybe, Dutch-born inventor, constructed the world's first aerial lift in Gdańsk in 1644.

- Jan Jonston, Polish scholar and physician of Scottish descent; author of Thautomatographia naturalis (1632) and Idea universae medicinae practicae (1642)

- Michał Sędziwój, Polish alchemist, philosopher, and medical doctor; a pioneer of chemistry, he developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other chemical compounds; he discovered that air is not a single substance and contains a life-giving substance-later called oxygen 170 years before similar discoveries by Scheele and Priestley; he correctly identified this 'food of life' with the gas (also oxygen) given off by heating nitre (saltpetre); this substance, the 'central nitre', had a central position in Sendivogius' schema of the universe.[234]

1501–1600

- Bartholomäus Keckermann, A Short Commentary on Navigation (the first one written in Poland)

- Josephus Struthius, he published in 1555 Sphygmicae artis iam mille ducentos perditae et desideratae libri V. in which he described five types of pulse, the diagnostic meaning of those types, and the influence of body temperature and nervous system on pulse. This was one of books used by William Harvey in his works

- Sebastian Petrycy, Polish philosopher and physician who lectured and published notable works in the field of medicine.[235]

- Nicolaus Copernicus, Renaissance polymath—an astronomer, mathematician, physician, lawyer, clergyman, governor, diplomat, military leader, classics scholar and economist, who developed the heliocentric theory in a form detailed enough to make it scientifically useful. His De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres) was published in 1543. He also described "Gresham's law" the year (1519) that Thomas Gresham was born.[236]

- King of Poland, Stephen Báthory founded the Vilnius University in 1579, which became the easternmost university in Europe.[237]

- Marcin of Urzędów, Polish Roman Catholic priest, physician, pharmacist and botanist known especially for his Herbarz polski ("Polish Herbal")

- Adam of Łowicz, Polish physician, philosopher, and humanist; author of Fundamentum scienciae nobilissimae secretorum naturae.[238]

- Albert Brudzewski, Polish astronomer, mathematician, philosopher and diplomat. He was the author of Commentum planetarium in theoricas Georgii Purbachii and was the first to state that the Moon moves in an ellipse and always shows its same side to the Earth.[239]

- Bishop Jan Lubrański founded the university college known as the Lubrański Academy in 1518.[240]

Middle Ages

- Kraków Academy (Akademia Krakowska) was founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great.

- Witelo (ca. 1230 – ca. 1314), was a philosopher and a scientist who specialized in optics. His famous optical treatise, Perspectiva, which drew on the Arabic Book of Optics by Alhazen, was unique in Latin literature and helped give rise to Roger Bacon's best work. In 1284, he described the reflection and refraction of light.[241] In addition to optics, Witelo's treatise made important contributions to the psychology of visual perception.

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.