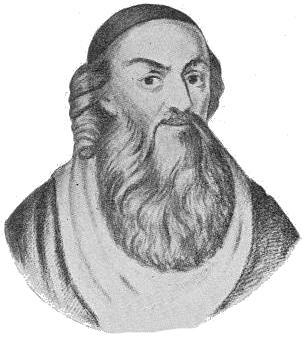

Albert Brudzewski

Polish academic and diplomat (c. 1445 - c. 1497) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Albert Brudzewski,[b] also known as Albert Blar (of Brudzewo),[1][2] Adalbertus,[3]Albert of Brudzewo or Albert of Brudzew (Polish: Wojciech Brudzewski: Latin: Albertus de Brudzewo; c.1445–c.1497) was a Polish astronomer, philosopher and diplomat. A major accomplishment of Albert's was his modernization of the teaching of astronomy by introducing the most up-to-date texts. He was an influential teacher to Nicolaus Copernicus, who initiated the Copernican Revolution.

Albert Brudzewski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1445 Brudzew/Brudzewo,[a] Kingdom of Poland |

| Died | c. 1497 (aged 51–52) |

| Alma mater | Kraków Academy |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy Mathematics philosophy |

| Institutions | Kraków Academy |

| Notable students | Nicolaus Copernicus, Bernard Wapowski, Conrad Celtes |

Later in his life he was secretary and diplomat of Alexander Jagiellon, Grand Duke of Lithuania.

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Albert (Polish: Wojciech), who would sign himself "de Brudzewo" ("of Brudzewo"), was born about 1445 in the city of Brudzew/Brudzewo,[a] in the Kingdom of Poland.

He matriculated at the Kraków Academy (now Jagiellonian University), where he earned his bachelor degree in 1470 and a master in 1474.[4] Brudweski was a student of Michał Falkener in physical sciences and of John of Głogów in mathematics.[5] Brudzewski may have also been a disciple of German astronomer Regiomontanus at the University of Vienna.[6][7] Brudzewski was well versed in Georg von Peuerbach's Theoricae novae planetarum and Regiomontanus' Tabulae directionum and Ephemerides.[1][6]

He drew up tables for calculating the positions of heavenly bodies. In 1482 he wrote a Commentariolum super Theoricas novas — a commentary on Peuerbach's text, which was published in Milan in 1495.[8][4] Peuerbach noted that Mercury does not describes a perfect circle but an oval-shaped orbit. Brudweski in his 1482 commentary remarks that the Moon follows a similar orbit, as it always shows its same side to the Earth.[8] As previously done by Sandivogius of Czechel, Brudweski added a secondary epicycle to explain the motion of the Moon.[6][9]

Brudzewski also considered that the motion of the planets was influenced by the Sun as their source of power.[10]

Other works include Introductorium Astronomorum Cracoviensium;Tabula resoluta Astronomic pro supputandis motibus corporum cœlestium and De Constructone Astrolabii.[5]

Teaching

Brudzewski is also remembered as a remarkable teacher. Filippo Buonaccorsi (Callimachus) wrote in a letter:[4]

Everything created by the keen perceptions of Euclides and Ptolemaeus, [Brudzewski] made a part of his intellectual property. All that remained deeply hidden to lay eyes, he knew how to set before the eyes of his pupils

At the Kraków Academy he impressed students by his extraordinary knowledge of literature, and taught mathematics and astronomy.[11] From 1489 to 1491, German poet and Renaissance humanist, Conrad Celtes traveled to Poland to meet and learn astrology from Brudzewski.[1][2] They became friends and exchanged letters even after Celtes departure.[1][2]

Brudzewski lectured on arithmetic, optics, Peuerbach astronomy and Mashallah ibn Athari works.[4] In 1490, he earned a bachelor in theology,[4] and from then onwards he lectured only on Aristotle's philosophy and his work On the Heavens.[8] These lectures were attended by Nicolaus Copernicus, who enrolled at the academy from 1491 to 1495.[11] It is possible that Brudzweski also discussed other topics with Copernicus privately.[4] Cartographer and friend of Copernicus Bernard Wapowski also studied under Brudzewski.[11]

Depart to Vilnius

In 1494, Brudzewski left Krakow.[8] In Vilnius, he engaged as secretary at the service of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Aleksander Jagiellon, who will later become King of Poland after the death of Brudzewki.[7][4] It was in Vilnius that Albert wrote his treatise, Conciliator, the original of which has not yet been found.[citation needed]

Albert of Brudzewo died in Vilnius circa 1497.

Views and contributions

Summarize

Perspective

On Averroes

Brudzewski was seen as influential and persuasive astronomer, a fictionalist, and an opponent of Middle Ages Andalusian scholar Averroes (Ibn Rushd). Averroes disagreed with the majority of the astronomer Ptolemy's work. He believed that Ptolemy's devices and principles disobeyed the fundamental principles and basic consequences of Aristotelian physics. Averroes worked to replace the Ptolemaic astronomical system with a novel system that was similar to a system created by Eudoxus. Albert Brudzewski disagreed and criticized Averroes immediately. The major dispute was the figuring out the number of celestial orbs or spheres that lay in the heavens. Averroes refused to believe that there was a ninth sphere in the heavens. He believed that the creation of all celestial beings had to arise from the stars, but the ninth sphere did not possess any stars, so this could not be true. Albert Brudzewski argued with this and said that the heavens possessed more than ten spheres. He believed that the Sun itself had three spheres and the planets had their own as well.[12]

To make sense and clarify to his followers, Brudzewski said that the terms 'orb' or 'sphere' had three meanings of interpretation. The first meaning could be the whole entire heavens was designated into a single object which was the orb or sphere. This object was not separate from the whole heavens yet it could exist by itself. The second meaning he paralleled it to the sphere or orb from Peurbach's Theoricae novae planetarum although it was unconventional, it still existed in the heavens. The third meaning or clarification of orb was an orb that was aligned with the Earth. The third meaning was actually a collection of orbs that was crucial to the motion of a planet.[12]

Brudzewski further disputes Averroes by depending on the assumptions of Aristotle. He said that Aristotle demonstrated and verified five claims about the heavens that could disprove Averroes. The first claim was that the heavens was a simple being. The second claim was that because the heavens was a simple being, the motion of the being also had to be simple and uncomplicated. There could only be one motion and it had to follow the laws of nature. The third claim was that any motion that did not follow the laws of nature had to have an addition motion that did follow the laws of nature. The fourth claim was that a single sphere or orb could not be moved by several motions because it was a simple body. The fifth claim was that any superior or greater orb could have an impact on lesser orbs and spheres but the lesser orbs and spheres could not have any leverage on the superior's ones.[12]

To finally disprove Averroes, Brudzewski mentions the three recognizable motions of the sphere of fixed stars. The first motion was that the sphere possessed a daily rotation that occurred from the East to the West. The second motion was movement of the sphere in the opposition direction from West to East. The third motion was a cyclical motion that Brudzewski named trepidation. Brudzewski gave these three motions to the last three spheres respectively. With the assumptions of Aristotle as well as the motions of the sphere of the fixed stars, Brudzewski is able to prove that Averroes is wrong about the number of celestial spheres in the heavens.[12]

On the heavens and planetary motion

Albert Brudzewski was known as a fictionalist. He did not think that the motions of the heavens were understood by any human.[13] Richard of Wallingford, an astronomer in the 1300s, had an opposing view for the spheres of the planets. He claimed that no mortal knows whether eccentrics truly exist in the spheres of the planets, but spirits could give humans revelations about the true planetary motion of the heavens through mathematicians.[12] This claim limits the astronomical knowledge of mortals and suggests that spirits do not have the same limitations. Brudzewski acknowledges the existence of these viewpoints but criticized their validity. To astronomers, spirits had an accurate knowledge of the number of celestial orbs. Although, he did not want to discredit the ability of mortals to make claims based on astronomical observations.Brudzewski made the claim for the fundamental principle of astrology that the heavens exert causal influences on the Earth.[12]

The paths of planets were thought to be moved by orbs instead of circles. This was a claim by Brudzeski about causal relationships between the planets and their motion. With this view, he disagreed with Averroes about the number of orbs, the concept of epicycles and eccentric circles, and on theoretical orbs. Brudzewski was seen as a source for some of Copernicus's work on orbs, specifically with the Tusi couple.[12]

Tusi couple

The Tusi couple was known as an epicycle arrangement that creates straight line motion of the planets, created by Copernicus.[14] Some think that Brudzewski is the source for Copernicus's model of the Tusi couple. Albert does account for the moon and its double epicycles where he mentions a spot on the moon.[12] The spot on the Moon is the problem of explaining the appearance of the face of the Moon when always viewing the Earth. These views were not aligned with the Tusi couple. Although, it is speculated that Copernicus could have encountered such a model, where the primary epicycle carries the center of a second epicycle. This is not the Tusi couple, but it could be slightly changed to match its model. The spot on the moon that is always viewed from the Earth would not appear if there was no epicyclical motion of the moon. The motion of the moon was termed as prosneusis motion which was part of the lunar theory. This motion means motion of inclination and turning, which corresponds to the single epicycle in Ptolemy's theory of the moon, and the two epicycles in Brudzewski's model.[12]

Brudzewski was aware of the possibility of linear motions from circular motions based on his model of Mercury's motion. This could be an alternative way that Copernicus generated his idea of linear motion for the Tusi couple. Although it seems that Copernicus used Albert's ideas, he highly relied on Islamic sources for the Tusi couple. Copernicus's parameters for the moon are exactly the same as those of Ibn al-Shatir. It is unclear where Copernicus truly got his ideas.[12]

On philosophy

Brudzewski was nominalist, but defended humanism.[4] Along with Cracow Academy, Brudzewski sided with the advocates of philosophical realism in the defense of scholasticism.[4]

In popular culture

A fictionalized version of Albert Brudzewski is the protagonist of the final part of the 2020 manga series Orb: On the Movements of the Earth, which was adapted into an anime in 2024.[15]

Notes

- It uncertain in which "Brudzewo"/"Brudzew" he was born: probably the town in present-day Brudzew, Kalisz County, see also Brudzew (disambiguation) and Brudzewo (disambiguation)

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.