Loading AI tools

French-American mathematician (1924–2010) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Benoit B.[n 1] Mandelbrot[n 2] (20 November 1924 – 14 October 2010) was a Polish-born French-American mathematician and polymath with broad interests in the practical sciences, especially regarding what he labeled as "the art of roughness" of physical phenomena and "the uncontrolled element in life".[6][7][8] He referred to himself as a "fractalist"[9] and is recognized for his contribution to the field of fractal geometry, which included coining the word "fractal", as well as developing a theory of "roughness and self-similarity" in nature.[10]

Benoit[n 1] Mandelbrot | |

|---|---|

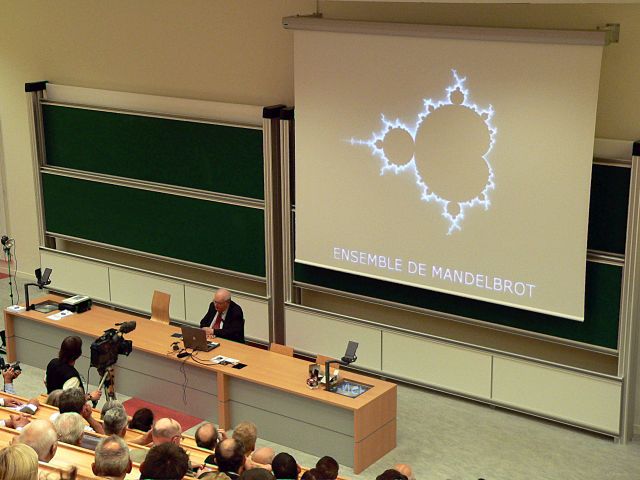

Mandelbrot at a TED conference in 2010 | |

| Born | 20 November 1924 |

| Died | 14 October 2010 (aged 85) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality |

|

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique California Institute of Technology University of Paris |

| Known for | |

| Spouse(s) | Aliette Kagan (m. 1955–2010; his death) |

| Awards | 2003 Japan Prize 1993 Wolf Prize 1989 Harvey Prize 1986 Franklin Medal 1985 Barnard Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Paul Lévy |

| Doctoral students | |

In 1936, at the age of 11, Mandelbrot and his family emigrated from Warsaw, Poland, to France. After World War II ended, Mandelbrot studied mathematics, graduating from universities in Paris and in the United States and receiving a master's degree in aeronautics from the California Institute of Technology. He spent most of his career in both the United States and France, having dual French and American citizenship. In 1958, he began a 35-year career at IBM, where he became an IBM Fellow, and periodically took leaves of absence to teach at Harvard University. At Harvard, following the publication of his study of U.S. commodity markets in relation to cotton futures, he taught economics and applied sciences.

Because of his access to IBM's computers, Mandelbrot was one of the first to use computer graphics to create and display fractal geometric images, leading to his discovery of the Mandelbrot set in 1980. He showed how visual complexity can be created from simple rules. He said that things typically considered to be "rough", a "mess", or "chaotic", such as clouds or shorelines, actually had a "degree of order".[11] His math- and geometry-centered research included contributions to such fields as statistical physics, meteorology, hydrology, geomorphology, anatomy, taxonomy, neurology, linguistics, information technology, computer graphics, economics, geology, medicine, physical cosmology, engineering, chaos theory, econophysics, metallurgy, and the social sciences.[12]

Toward the end of his career, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences at Yale University, where he was the oldest professor in Yale's history to receive tenure.[13] Mandelbrot also held positions at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Université Lille Nord de France, Institute for Advanced Study and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. During his career, he received over 15 honorary doctorates and served on many science journals, along with winning numerous awards. His autobiography, The Fractalist: Memoir of a Scientific Maverick, was published posthumously in 2012.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Benedykt Mandelbrot[15] was born in a Lithuanian Jewish family, in Warsaw during the Second Polish Republic.[16] His father made his living trading clothing; his mother was a dental surgeon. During his first two school years, he was tutored privately by an uncle who despised rote learning: "Most of my time was spent playing chess, reading maps and learning how to open my eyes to everything around me."[17] In 1936, when he was 11, the family emigrated from Poland to France. The move, World War II, and the influence of his father's brother, the mathematician Szolem Mandelbrojt (who had moved to Paris around 1920), further prevented a standard education. "The fact that my parents, as economic and political refugees, joined Szolem in France saved our lives," he writes.[9]: 17 [18]

Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rollin (now the Collège-lycée Jacques-Decour) in Paris until the start of World War II, when his family moved to Tulle, France. He was helped by Rabbi David Feuerwerker, the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde, to continue his studies.[9]: 62–63 [19] Much of France was occupied by the Nazis at the time, and Mandelbrot recalls this period:

Our constant fear was that a sufficiently determined foe might report us to an authority and we would be sent to our deaths. This happened to a close friend from Paris, Zina Morhange, a physician in a nearby county seat. Simply to eliminate the competition, another physician denounced her ... We escaped this fate. Who knows why?[9]: 49

In 1944, Mandelbrot returned to Paris, studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon, and in 1945 to 1947 attended the École Polytechnique, where he studied under Gaston Julia and Paul Lévy. From 1947 to 1949 he studied at California Institute of Technology, where he earned a master's degree in aeronautics.[2] Returning to France, he obtained his PhD degree in Mathematical Sciences at the University of Paris in 1952.[17]

From 1949 to 1958, Mandelbrot was a staff member at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. During this time he spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he was sponsored by John von Neumann. In 1955 he married Aliette Kagan and moved to Geneva, Switzerland (to collaborate with Jean Piaget at the International Centre for Genetic Epistemology) and later to the Université Lille Nord de France.[20] In 1958 the couple moved to the United States where Mandelbrot joined the research staff at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York.[20] He remained at IBM for 35 years, becoming an IBM Fellow, and later Fellow Emeritus.[17]

From 1951 onward, Mandelbrot worked on problems and published papers not only in mathematics but in applied fields such as information theory, economics, and fluid dynamics.

Mandelbrot saw financial markets as an example of "wild randomness", characterized by concentration and long-range dependence. He developed several original approaches for modelling financial fluctuations.[21] In his early work, he found that the price changes in financial markets did not follow a Gaussian distribution, but rather Lévy stable distributions having infinite variance. He found, for example, that cotton prices followed a Lévy stable distribution with parameter α equal to 1.7 rather than 2 as in a Gaussian distribution. "Stable" distributions have the property that the sum of many instances of a random variable follows the same distribution but with a larger scale parameter.[22] The latter work from the early 60s was done with daily data of cotton prices from 1900, long before he introduced the word 'fractal'. In later years, after the concept of fractals had matured, the study of financial markets in the context of fractals became possible only after the availability of high frequency data in finance. In the late 1980s, Mandelbrot used intra-daily tick data supplied by Olsen & Associates in Zurich[23][24] to apply fractal theory to market microstructure. This cooperation led to the publication of the first comprehensive papers on scaling law in finance.[25][26] This law shows similar properties at different time scales, confirming Mandelbrot's insight of the fractal nature of market microstructure. Mandelbrot's own research in this area is presented in his books Fractals and Scaling in Finance[27] and The (Mis)behavior of Markets.[28]

As a visiting professor at Harvard University, Mandelbrot began to study mathematical objects called Julia sets that were invariant under certain transformations of the complex plane. Building on previous work by Gaston Julia and Pierre Fatou, Mandelbrot used a computer to plot images of the Julia sets. While investigating the topology of these Julia sets, he studied the Mandelbrot set which was introduced by him in 1979.

In 1975, Mandelbrot coined the term fractal to describe these structures and first published his ideas in the French book Les Objets Fractals: Forme, Hasard et Dimension, later translated in 1977 as Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension.[29] According to computer scientist and physicist Stephen Wolfram, the book was a "breakthrough" for Mandelbrot, who until then would typically "apply fairly straightforward mathematics ... to areas that had barely seen the light of serious mathematics before".[11] Wolfram adds that as a result of this new research, he was no longer a "wandering scientist", and later called him "the father of fractals":

Mandelbrot ended up doing a great piece of science and identifying a much stronger and more fundamental idea—put simply, that there are some geometric shapes, which he called "fractals", that are equally "rough" at all scales. No matter how close you look, they never get simpler, much as the section of a rocky coastline you can see at your feet looks just as jagged as the stretch you can see from space.[11]

Wolfram briefly describes fractals as a form of geometric repetition, "in which smaller and smaller copies of a pattern are successively nested inside each other, so that the same intricate shapes appear no matter how much you zoom in to the whole. Fern leaves and Romanesque broccoli are two examples from nature."[11] He points out an unexpected conclusion:

One might have thought that such a simple and fundamental form of regularity would have been studied for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. But it was not. In fact, it rose to prominence only over the past 30 or so years—almost entirely through the efforts of one man, the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot.[11]

Mandelbrot used the term "fractal" as it derived from the Latin word "fractus", defined as broken or shattered glass. Using the newly developed IBM computers at his disposal, Mandelbrot was able to create fractal images using graphics computer code, images that an interviewer described as looking like "the delirious exuberance of the 1960s psychedelic art with forms hauntingly reminiscent of nature and the human body". He also saw himself as a "would-be Kepler", after the 17th-century scientist Johannes Kepler, who calculated and described the orbits of the planets.[30]

Mandelbrot, however, never felt he was inventing a new idea. He described his feelings in a documentary with science writer Arthur C. Clarke:

Exploring this set I certainly never had the feeling of invention. I never had the feeling that my imagination was rich enough to invent all those extraordinary things on discovering them. They were there, even though nobody had seen them before. It's marvelous, a very simple formula explains all these very complicated things. So the goal of science is starting with a mess, and explaining it with a simple formula, a kind of dream of science.[31]

According to Clarke, "the Mandelbrot set is indeed one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics. Who could have dreamed that such an incredibly simple equation could have generated images of literally infinite complexity?" Clarke also notes an "odd coincidence":

the name Mandelbrot, and the word "mandala"—for a religious symbol—which I'm sure is a pure coincidence, but indeed the Mandelbrot set does seem to contain an enormous number of mandalas.[31]

In 1982, Mandelbrot expanded and updated his ideas in The Fractal Geometry of Nature.[32] This influential work brought fractals into the mainstream of professional and popular mathematics, as well as silencing critics, who had dismissed fractals as "program artifacts".

Mandelbrot left IBM in 1987, after 35 years and 12 days, when IBM decided to end pure research in his division.[33] He joined the Department of Mathematics at Yale, and obtained his first tenured post in 1999, at the age of 75.[34] At the time of his retirement in 2005, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences.

Mandelbrot created the first-ever "theory of roughness", and he saw "roughness" in the shapes of mountains, coastlines and river basins; the structures of plants, blood vessels and lungs; the clustering of galaxies. His personal quest was to create some mathematical formula to measure the overall "roughness" of such objects in nature.[9]: xi He began by asking himself various kinds of questions related to nature:

Can geometry deliver what the Greek root of its name [geo-] seemed to promise—truthful measurement, not only of cultivated fields along the Nile River but also of untamed Earth?[9]: xii

In his paper "How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension", published in Science in 1967, Mandelbrot discusses self-similar curves that have Hausdorff dimension that are examples of fractals, although Mandelbrot does not use this term in the paper, as he did not coin it until 1975. The paper is one of Mandelbrot's first publications on the topic of fractals.[35][36]

Mandelbrot emphasized the use of fractals as realistic and useful models for describing many "rough" phenomena in the real world. He concluded that "real roughness is often fractal and can be measured."[9]: 296 Although Mandelbrot coined the term "fractal", some of the mathematical objects he presented in The Fractal Geometry of Nature had been previously described by other mathematicians. Before Mandelbrot, however, they were regarded as isolated curiosities with unnatural and non-intuitive properties. Mandelbrot brought these objects together for the first time and turned them into essential tools for the long-stalled effort to extend the scope of science to explaining non-smooth, "rough" objects in the real world. His methods of research were both old and new:

The form of geometry I increasingly favored is the oldest, most concrete, and most inclusive, specifically empowered by the eye and helped by the hand and, today, also by the computer ... bringing an element of unity to the worlds of knowing and feeling ... and, unwittingly, as a bonus, for the purpose of creating beauty.[9]: 292

Fractals are also found in human pursuits, such as music, painting, architecture, and in the financial field. Mandelbrot believed that fractals, far from being unnatural, were in many ways more intuitive and natural than the artificially smooth objects of traditional Euclidean geometry:

Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.

—Mandelbrot, in his introduction to The Fractal Geometry of Nature

Mandelbrot has been called an artist, and a visionary[37] and a maverick.[38] His informal and passionate style of writing and his emphasis on visual and geometric intuition (supported by the inclusion of numerous illustrations) made The Fractal Geometry of Nature accessible to non-specialists. The book sparked widespread popular interest in fractals and contributed to chaos theory and other fields of science and mathematics.

Mandelbrot also put his ideas to work in cosmology. He offered in 1974 a new explanation of Olbers' paradox (the "dark night sky" riddle), demonstrating the consequences of fractal theory as a sufficient, but not necessary, resolution of the paradox. He postulated that if the stars in the universe were fractally distributed (for example, like Cantor dust), it would not be necessary to rely on the Big Bang theory to explain the paradox. His model would not rule out a Big Bang, but would allow for a dark sky even if the Big Bang had not occurred.[39]

Mandelbrot's awards include the Wolf Prize for Physics in 1993, the Lewis Fry Richardson Prize of the European Geophysical Society in 2000, the Japan Prize in 2003,[40] and the Einstein Lectureship of the American Mathematical Society in 2006.

The small asteroid 27500 Mandelbrot was named in his honor. In November 1990, he was made a Chevalier in France's Legion of Honour. In December 2005, Mandelbrot was appointed to the position of Battelle Fellow at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.[41] Mandelbrot was promoted to an Officer of the Legion of Honour in January 2006.[42] An honorary degree from Johns Hopkins University was bestowed on Mandelbrot in the May 2010 commencement exercises.[43]

A partial list of awards received by Mandelbrot:[44]

Mandelbrot died from pancreatic cancer at the age of 85 in a hospice in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on 14 October 2010.[1][50] Reacting to news of his death, mathematician Heinz-Otto Peitgen said: "[I]f we talk about impact inside mathematics, and applications in the sciences, he is one of the most important figures of the last fifty years."[1]

Chris Anderson, TED conference curator, described Mandelbrot as "an icon who changed how we see the world".[51] Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France at the time of Mandelbrot's death, said Mandelbrot had "a powerful, original mind that never shied away from innovating and shattering preconceived notions [... h]is work, developed entirely outside mainstream research, led to modern information theory."[52] Mandelbrot's obituary in The Economist points out his fame as "celebrity beyond the academy" and lauds him as the "father of fractal geometry".[53]

Best-selling essayist-author Nassim Nicholas Taleb has remarked that Mandelbrot's book The (Mis)Behavior of Markets is in his opinion "The deepest and most realistic finance book ever published".[10]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.