Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Plain tobacco packaging

Legally mandated packaging of tobacco products without any brand imagery From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

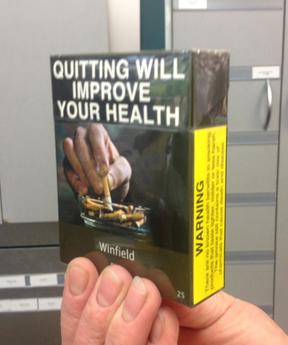

Plain tobacco packaging, also known as generic, neutral, standardised or homogeneous packaging, is packaging of tobacco products, typically cigarettes, without any branding (colours, imagery, corporate logos and trademarks), including only the brand name in a mandated size, font and place on the pack, in addition to the health warnings and any other legally mandated information such as toxic constituents and tax-paid stamps. The appearance of all tobacco packs is standardised, including the colour of the pack.

The removal of branding on cigarette packaging is a regulation of nicotine marketing and aims to deter smoking by removal of positive associations of brands (including design and symbol) with the consumption of tobacco. It also aims to remove an available avenue of brand advertising for cigarette companies.

Australia was the first country in the world to introduce plain packaging, with all packets sold from 1 December 2012 being sold in logo-free, drab dark brown packaging. There has been opposition from tobacco companies to plain packaging laws, some of which have sued the Australian government in Australian and international courts. Since the Australian government won the court cases, several other countries have enacted plain packaging laws.

Plain packaging was included in guidelines to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). On 31 May 2016, on World No Tobacco Day, the WHO called on governments to get ready for plain packaging of tobacco products.[1]

Similar packaging restrictions have also been proposed for confectioneries, sugary drinks and other consumables widely regarded as unhealthy, but none appear to have been implemented so far.[2][3]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Plain packaging appears to have been first suggested in 1989 by the New Zealand Department of Health's Toxic Substances Board which recommended that cigarettes be sold only in white packs with black text and no colours or logos.[4]

Public health officials in Canada developed proposals for plain packaging of tobacco products in 1994. A parliamentary committee reviewed the evidence and concluded that plain packaging could be a "reasonable step in the overall strategy to reduce tobacco consumption".[5] This effort did not succeed due to trademark right concerns, specifically those related to Canada's commitments to the World Trade Organization and under the North American Free Trade Agreement.[6]

Australia, with the enactment of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act on 12 December 2011,[7] became the first country in the world to require tobacco products to be sold in plain packaging.[8] Products manufactured after 1 October 2012, and all on sale after 1 December 2012 must be in the plain packaging.[9][10]

Following Australia's lead, a number of other countries also began requiring standardized packaging including France (January 2017); the United Kingdom (May 2017); New Zealand (June 2018); Norway (July 2018); Ireland (September 2018); Thailand and Uruguay (December 2019); Saudi Arabia, Israel, Slovenia[11] and Turkey (January 2020); Canada (February 2020); Singapore (July 2020); Belgium (January 2021) the Netherlands (October 2021) and Georgia (April 2025).

Remove ads

Evidence

Summarize

Perspective

Only indirect evidence of plain packaging's effectiveness was available until its release in Australia. On 24 May 2011, Cancer Council Australia released a review of the evidence supporting the introduction of plain packaging to reduce youth uptake.[12] The review had been conducted by Quit Victoria and Cancer Council Victoria. The review includes 24 peer-reviewed studies conducted over two decades, suggesting that packaging plays an important role in encouraging young people to try cigarettes.[13] First impressions in Australia indicated that smokers feel that cigarettes taste worse in plain packaging – an unexpected side effect.[14][15] In addition, evidence from quantitative studies, qualitative research and the internal documents of the tobacco industry consistently identify packaging as an important part of tobacco promotion. Smoking among Australian teenagers (12–17 year old and 18–19 year old) decreased between 2013 and 2016 from 3.4% to 1.5% and from 10.8% to 4.6% respectively.[16]

There have been three studies that have assessed the change in smoking prevalence or in the sales of cigarettes subsequent to Plain Packaging (PP) implementation. A study by Scollo et al.[17] reported consumption did not seem to decline in the year immediately after PP but declined following the December 2013 tax increase, from 14.8% to 14% (i.e. a decline of 5.7%). It was based upon a national cross-sectional telephone surveys of adult smokers conducted from April 2012 (6 months before transition to plain packaging) to March 2014 (15 months afterwards). Conclusions were that the introduction of PP was associated with an increase in use of value brands, likely due to increased numbers available, and smaller increases in prices for these brands relative to the premium brands.

A US consultant was commissioned by the Australian Government's Department of Health to undertake a study of the effectiveness of Plain Packaging legislation on smoking prevalence. The consultant's report[18] found that there were fewer smokers after the PP legislation was implemented as there was a statistically significant decline in smoking rates. The Report's Conclusion states: "In terms of order of magnitude, smoking prevalence is 0.55 percentage points lower over the period December 2012 to September 2015 than it would have been without the packaging changes. For reasons I have explained, this effect is likely understated and is expected to grow over time." Data used was from a commercial firm, Roy Morgan, that conducted a nationally representative, repeated cross-sectional survey that asked each of about 4,500 participants aged 14 and above a series of smoking-related questions. The sample is different each month.

A further study by Bonfrer et al.[19] found that overall cigarette consumption in Australia dropped by 7.5 percent over the post PP implementation period investigated. Using the retail cigarette industry's quality classifications (value, mainstream, and premium), it was found that market share declined among premium and mainstream brands but increased for the cheaper value brands. Accompanying the declines in market shares, price sensitivity increased for mainstream and value brands across both grocery and convenience channels, according to the research. The only exception was short-term price sensitivity for premium and mainstream brands in the convenience channel, which was observed to decline following PP implementation. This study used 4-weekly data on 42 brands on their sales volumes and prices through (a) Supermarkets and, separately, through (b) Convenience stores, in Australia. The period covered was from late 2008 through to mid-2014, that is covering sales both before and after the implementation of PP. A distinguishing methodological feature of this study was that it used a control to assess changes in sales, compared to the methods used in the earlier studies.

Plain packaging can change people's attitudes towards smoking and may help reduce the prevalence of smoking, including among minors, and increase attempts to quit.[20][21][22]

Studies comparing existing branded cigarette packs with plain cardboard packs bearing the name and number of cigarettes in small standard font, found plain packs to be significantly less attractive.[23][24] Additionally, research in which young adults were instructed to use plain cigarette packs and subsequently asked about their feelings towards them confirmed findings that plain packaging increased negative perceptions and feelings about the pack and about smoking. Plain packs also increased behaviours such as hiding or covering the pack, smoking less around others, going without cigarettes and increased thinking about quitting. Almost half of the participants reported that plain packs had either increased the above behaviours or reduced consumption.[25] Auction experiments indicated that a likely outcome of plain packaging would be to drive down demand of tobacco products.[26]

A 2013 review found that plain packaging increased the importance of health warnings to consumers. Plain packaging in a darker colour was associated with more harmful effects.[27] Furthermore, plain packaging reduced confusion about health warnings.[28]

Plain packaging with large, graphic, warnings, was considered to impact on smoking cessation.[29]

There is little evidence yet as to what effect plain packaging will have on smoking in lower-income countries.[30]

Remove ads

Opposition

Summarize

Perspective

Advertisement companies and consultants for the tobacco industry expressed concerns that plain cigarette packaging may establish a precedent for application in other industries.[31] In 2012, correspondence between Mars, Incorporated and the UK Department of Health conveyed concerns that plain packaging could be extended to the food and beverage industry.[32][33] Together, with other policies such as tobacco taxes, plain packaging is considered by some as a form of social engineering.[34][35]

A study commissioned by Philip Morris International indicated that plain packaging would shift consumer preferences away from premium towards cheaper brands.[36]

The tobacco industry also expressed concern that plain packaging would increase the sales of counterfeit cigarettes. Roy Ramm, former commander of Specialist Operations at New Scotland Yard and founding member of The Common Sense Alliance,[37] a think tank supported by British American Tobacco,[38] stated that it would be "disastrous if the government, by introducing plain-packaging legislation, [removed] the simplest mechanism for the ordinary consumer to tell whether their cigarettes are counterfeit or not."[39]

Arguments against plain packaging include its effect on smuggling, its effect on shops and retailers, and its possible illegality. A study published in July 2014 by the BMJ rebutted those claims.[40]

In reporting Philip Morris's legal action against the Australian project, The Times of India noted in 2011 that plain packaging legislation was being closely watched by other countries, and that tobacco firms were worried the Australian plain packaging legislation might set a global precedent.[41]

In July 2012, it was reported that the American lobbying organisation American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) had launched a worldwide campaign against plain packaging of cigarettes. With the backing of tobacco companies and other corporate interests, it targeted governments planning to introduce bans on cigarette branding, including the UK and Australia.[42] Tobacco companies were also reported to have provided legal advice and funding to Ukraine and Honduras governments to launch a complaint in the World Trade Organization (WTO) on the grounds that the Australian legislation is contrary to a WTO intellectual property agreement. WTO complaints must be made by Governments, not companies.[43] British American Tobacco confirmed that they were helping Ukraine meet legal costs in their case against Australia.[44]

By May 2013, Cuba,[45] Ukraine, Honduras and the Dominican Republic challenged Australia's rules through the WTO by filing requests for consultations, the first step in challenging Australia's tobacco-labelling laws at the WTO[7] A request for consultations opened a 60-day negotiation window after which a formal complaint could be filed which, if successful, might have led to increased tariffs on Australian exports. On 28 May 2015 Ukraine, which exports no tobacco to Australia, decided to suspend its WTO action initiated by the previous Ukrainian government.[44] The packaging of Cuban cigars is considered to contribute significantly to sales.[7]

In June 2018, the WTO panel rejected the claims of the plaignants. Regarding the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, the panel concludes that plain packaging restricts trade only insofar as it reduces consumption, which is the legitimate objective of the measure. As for the TRIPS Agreement, it observes that "TRIPS does not provide for a right to use a trademark", but prevents other companies from using them.[46] In June 2020, the Appellate Body rejected an appeal formed by Honduras and the Dominican Republic against the panel decision.[47]

Remove ads

By country

Summarize

Perspective

Plain packaging

Passed into law, but not yet in force

Furthermore, plain packaging has been implemented in practice in three countries where packages are imported from a country with plain packaging, i.e. ![]() Monaco (from France),

Monaco (from France), ![]() Cook Islands (from New Zealand), and

Cook Islands (from New Zealand), and ![]() Niue (from Australia).

Niue (from Australia).

Australia

Under the legislation, companies have had to sell their cigarettes in a logo-free, drab dark brown packaging from 1 December 2012.[52] Government research found that a specific olive green colour, Pantone 448 C, was the least attractive colour, particularly for young people.[53][54] After concerns were expressed over the naming of the colour by the Australian Olive Association, the name was changed to drab dark brown.[55] With the plain packaging and tax increases[56] the Australian government aimed to bring down smoking rates from 16.6% in 2007 to less than 10% by 2018.[57] Statistics published in 2014 showed that the amount of excise and customs duty on cigarettes fell by 3.4% in Australia in 2013 compared to 2012 when plain packaging was introduced.[58][59] Some commentators referred to data provided by the tobacco industry and claimed that the tobacco sales volume had increased by 59 million sticks (individual cigarettes or their roll-your-own equivalents) during the same period.[60][61] According to Philip Morris International, 2013 saw a 0.3% increase in tobacco sales compared to 2012.[62][63] Other commentators however contradicted these claims based on data published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in March 2014.[64][65][66] A study conducted by KPMG for three major cigarette manufacturers had found that illegal trade of drastically cheaper cigarettes had significantly increased,[67] but an article in The BMJ refutes this.[68] After one year of plain cigarette packaging rule implementation, a special supplement to the British Medical Journal described that before plain packaging implementation 20% of smokers want to quit, but after implementation 27% of smokers want to quit. The study found that plain packaging reduces brand appeal and brand image of tobacco products.[69] If true, this would foretell fewer new smokers taking up the habit. An analysis of claims made by Philip Morris that "the data is clear that overall tobacco consumption and smoking prevalence has not gone down" concluded that this "claim is wrong".[70] A 2016 review by the Australian Government found that the current packaging regime is having a positive impact on public health in Australia.[71]

Tobacco industry response

In August 2010, Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco and Imperial Tobacco formed the Alliance of Australian Retailers, which commenced a multimillion-dollar campaign against the introduction of plain cigarette packaging. The campaign focused on grassroots advocacy (astroturfing), ostensibly on behalf of small business owners.[72] When the funding source of the campaign was made public, large retailers such as Coles and Woolworths quickly withdrew support for the campaign.[73][74] The tobacco companies subsequently hired a public relations firm to oversee the campaign.[75]

In May 2011, British American Tobacco launched a media campaign suggesting that illicit trade and crime syndicates would benefit from plain packaging.[76] BATA CEO David Crow threatened to lower cigarette prices in order to compete, which he claimed could result in higher levels of smoking amongst young people.[77] Crow later commented he would tell his own children not to smoke cigarettes, because they are unhealthy.[78]

The BATA campaign is largely based on a report from Deloitte. Several of the claims contained in the report related to border protection, and have since been publicly refuted by customs officials, and the report itself indicated that it had relied extensively on unaudited figures supplied by the tobacco industry itself.[79][80]

In June 2011, Imperial Tobacco Australia launched a secondary media campaign, deriding plain packaging legislation as part of a nanny state.[81]

In June 2011, Philip Morris International announced it was using the provisions in a Hong Kong/Australia treaty to demand compensation for Australia's plain packaging anti-smoking legislation. As a US-based company, Philip Morris could not sue under the US-Australia Free Trade Agreement. The company rearranged its assets to become a Hong Kong investor in order to use the investor-state dispute settlement provisions in the Australia-Hong Kong Bilateral Investment treaty (BIT).[43] Immediately following the passage of legislation on 21 November 2011, Philip Morris announced it had served a notice of arbitration under Australia's Bilateral Investment Treaty with Hong Kong, seeking the suspension on the plain packaging laws and compensation for the loss of trademarks.[9] Allens Arthur Robinson represented Philip Morris.[82] In response, Health Minister Nicola Roxon stated that she believed the government was "on very strong ground" legally, and that the government was willing to defend the measures.[83][84] The continuance of trade and investment proceedings on the issue has been described as an affront to the rule of law in Australia.[85] Dr Patricia Ranald, Convener of the Australian Fair Trade and Investment Network said that big tobacco and other global corporations are lobbying hard to include the right of foreign investors to sue governments in the current negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA).[43] Philip Morris International lost its case in December 2015.[86]

In November 2011, British American Tobacco announced that it would challenge the laws in the High Court as soon as they gained royal assent.[87] In August 2012, the High Court ruled in favour of the Australian government.[88]

British American Tobacco placed freedom of information requests on a Cancer Institute NSW research survey of school students aged between 12 and 17, which asked how they react to plain packaging, where they get cigarettes from and what age they started smoking.[89][90] The Cancer Council Victoria fought the FOI request, saying that the tobacco company wanted to use the survey information to change their marketing to children to increase cigarette smoking among youth.

Phillip Morris was ordered to pay the Australian government's legal fees.[91] A FOI request by Nick Xenophon and Rex Patrick revealed that Australia's legal fees amounted to $39 million with Patrick saying that this showed the dangers of investor-state dispute settlement clauses allowing companies to sue governments in the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[92]

Other responses

The World Health Organization (WHO) applauded Australia's law on plain packaging noting that "the legislation sets a new global standard for the control of a product that accounts for nearly 6 million deaths each year".[93]

The Cancer Council of Australia hailed the passing of the legislation, stating, "Documents obtained from the tobacco industry show how much the tobacco companies rely on pack design to attract new smokers....You only have to look at how desperate the tobacco companies are to stop plain packaging, for confirmation that pack design is seen as critical to sales."[94] The WHO's director for the Western Pacific also congratulated Australia and stated that all countries and areas in the Western Pacific should follow Australia's good example.[95]

Speaking on Radio Australia, Don Rothwell, Professor of International Law at the Australian National University, noted that Philip Morris was pursuing multiple legal avenues. The Notice of Arbitration under the bilateral investment treaty between Hong Kong and Australia has a 90-day cooling off period after which the case would most likely be sent to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes in Washington. He stated that Philip Morris was most likely aiming for the Australian Government to back down, or failing that, to sue for compensation. He said the questions to decide are whether the legislation means that Australia would acquire property by the imposition of these rules and if this legislation is a legitimate public-health measure.

Professor Rothwell noted "...the growing recognition of the legitimacy of public health measures of this type." Professor Rothwell estimated that the legal cases, including any case before the High Court, would take up to a year to decide.[96] However, in the United States, Judge Richard J. Leon ruled in 2011 that graphic health warning labels "clearly display the government's opinion on smoking" which he said "cannot constitutionally be required to appear on the merchandise of private companies." He ruled that these warnings would unfairly hurt their sales, that the warnings were crafted to provoke an emotional response calculated to quit smoking or never to start smoking. This, the judge ruled, was "an objective wholly apart from disseminating purely factual and uncontroversial information." This finding may be appealed.[97][98][needs update]

The Associated Press noted that Philip Morris took "less than an hour" to launch legal action against the Australian legislation. It also stated that Australian legislation followed the lead of Uruguay which requires that 80 per cent of cigarette packages is devoted to warnings and Brazil, where cigarette packages display "graphic images" of dead fetuses, haemorrhaging brains and gangrenous feet.[99]

New Zealand Associate Health Minister Tariana Turia congratulated the Australian Health Minister, noted that tobacco labelling rules have long been harmonised between Australia and New Zealand, and looked forward to New Zealand following suit.[100]

Legislation

In April 2011, Minister Roxon released an exposure draft of plain packaging legislation with an expected start date of 1 July 2012.[101] Australian newspapers reported that the legislation was likely to pass despite concerns from the Opposition. It was suggested the Opposition resistance to the legislation was due to their continuing acceptance of funding donations from tobacco companies.[102]

On 31 May 2011, Liberal leader Tony Abbott announced that his party would support the legislation, and would work with the government to ensure the legislation is effective.[103]

Minister Roxon introduced the plain packaging bill to Parliament on 6 July 2011,[83] and it passed through the Lower House on 24 August 2011.[104] The legislation passed the Upper House on 10 November 2011 with the amended start date of 1 December 2012.[52] Due to the changed start date the legislation returned to the Lower House before being given royal assent.[105] Legislation finally passed on 21 November 2011.[9]

Belgium

In March 2015, an early day motion forwarded by deputy Catherine Fonck to consider plain packaging in Belgium. However, it was opposed and stuck down by the federal Public Health select committee.[106] Later in November 2016, the health minister Maggie De Block said she is open to idea of plain packaging, once the introduction of plain packaging in France and the UK has been reviewed. This was done on top of a list of new tobacco laws such as increasing taxes and raising the purchasing age to 18.[107]

In September 2018, the government decided to introduce plain packaging for all tobacco products.[108] The new law came in force in January 2020.[109]

Canada

During the 2015 Canadian federal election campaign, Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau promised to mandate plain packaging if elected prime minister.[110] On 16 May 2018, Parliament passed Bill S-5 to amend the Tobacco Act as the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act, adding the authority for Health Canada to mandate plain packaging for cigarette products (alongside extending many of its existing restrictions to electronic cigarettes).[111]

The Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance) were published to the Canada Gazette on 24 April 2019: plain packaging will use the same brown color used in Australia, and must use a standardized layout and "slide and shell" package. No other packaging styles are permitted. The cigarette itself may not include any branding or promotions, and cigarettes longer than 85 mm in length are also banned, as well as any "slim" cigarette. The phase-in has begun on 9 November 2019, and completed on 7 February 2020.[112] Canada has also opted for plain packaging and labelling for all cannabis products, with restrictions on logos, colours, branding and specific display formats.

Canada became the first country in the world to require health warnings on individual cigarettes and cigars, effective August 1, 2023, to be phased in over time when the regulation is fully in effect by April 2025.[113]

Colombia

In March 2015, a bill similar to the Australian one was established before the Congress of the Republic, since it was intended to regulate the packaging and labeling of tobacco products. The ultimate goal of this Bill was to achieve a total ban on its advertising, promotion and sponsorship. Although the Bill was filed a few months after the passage of the legislature, the one that has come to be debated in the first presentation in the House of Representatives allows concluding that Colombia is not far from adopting a regulation on the matter.[114]

Denmark

In December 2020, a law establishing plain packaging was passed by the Danish parliament, the Folketing. It states that only plain packs can be sold by retailers in Denmark as of 1 April 2022.[115] The law was promulgated on 21 December 2020.[116]

European Union

In 2010, the European Commission launched a public consultation[117] on a proposal to revise Directive 2001/37/EC which covers health warnings, limits on toxic constituents, etc., for tobacco products. The consultation included a proposal to require plain packaging. Although Commissioner Dalli rejected plain packaging as an option,[118] the European Union included in its proposal for a new Tobacco Products Directive, which became applicable in EU countries in May 2016,[119] the option for the Member States to introduce plain packaging.[120] Legal scholars consider plain packaging to be consistent with primary European law[121] and German law.[122]

The directive adopted 3 April 2014 explicitly states that 28 EU countries have the option of implementing plain packaging, a provision upheld on 4 May 2016 by the European Court of Justice as valid when dismissing a tobacco industry legal challenge.[123]

Finland

Finland has introduced a bill that includes provisions for a plain packaging scheme.[124]

France

In December 2010, a UMP member of the French Parliament tabled a Member's Bill aimed at creating plain cigarette packaging. However, the bill did not pass despite ongoing support from health associations.[125] As in other countries, there was fierce protest from the tobacco industry and tobacco retailers associations. The Health Minister also seemed lukewarm in his support, preferring to see the effect of newly introduced health warnings.[126]

Under the next legislature however, the new Socialist Health Minister, Marisol Touraine, said she would fight especially at the European level for "neutral packaging". As in Australia, the tobacco industry countered that generic packaging would be easy to counterfeit, which would increase illegal cigarette sales.[127] The EU directive eventually contained no explicit measures regarding plain packaging. In reaction, the French government announced the introduction of a bill containing provisions for generic cigarette packaging on 25 September 2014.[128] The bill was passed on 17 December 2015. The tobacco industry promptly attacked it in court, but lost its case. This legislation was upheld on 21 January 2016 as constitutional by France's Constitutional Council.[129]

Cigarettes manufactured after 20 May 2016 or sold after 1 January 2017 in France (including overseas departments and regions of France) must be put in plain packaging.[130]

Georgia

In May 2017, the Georgian Parliament introduced a plain packaging law for implementation in 2018, then postponed to December 2022.[131] In December 2022, the date was further postponed to 31 July 2024.[132] it was finally approved in early 2025, coming into full effect on April 1.[133]

Germany

In 2022, then-Drogenbeauftragter der Bundesregierung (Federal Government Commissioner on Narcotic Drugs), Burkhard Blienert of the SPD, criticized Germany's tobacco policy as too lax and said that the introduction of neutral standardized packaging for tobacco should be considered.[134]

Guernsey

Plain packaging was introduced in Guernsey on 31 July 2021. A one-year transition period was introduced in order to allow retailers to sell off stock that did not conform.[135]

Hungary

The Decree of 16 August 2016 requires that new cigarette and tobacco brands that will be introduced on the Hungarian market after 20 August 2016 has to be in a uniform plain packaging, void of brand logos. Eventually, all cigarette and tobacco products are to be sold in uniform packs from 20 May 2019.[136] Entry into force has later been postponed to 1 January 2022.[137][138]

As of July 2017, the first cigarettes with unified plain packaging hit the Hungarian market. From 20 August 2016 onwards, new brands have to be sold in plain packaging. One new cigarette brand of Von Eicken GmbH have been launched with such unified package.

India

In August 2012, India was believed to be considering plain packaging.[139] Research into its feasibility was conducted in 2013.[140] BJD MP of Orissa, Baijayant Jay Panda, had unsuccessfully submitted in the Lok Sabha a Private member's bill seeking an amendment to the 2003 anti-tobacco law. The bill sought to stipulate for plain packaging of cigarette and tobacco products and increase the size of health warning and the accompanying graphic on cigarette packets.[141] In general, tobacco control measures are often prone to legal challenges in India.[140] So far, there has been no progress on this matter and tobacco continues to be sold in branded packaging.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare presented a draft of the bill on January 1, 2021 for public comment to be submitted by January 31. 2021.The bill proposes amending the existing act, which dates to 2003. But it contains no provision on plain packaging.[142]

Indonesia

In September 2024, the Ministry of Health planned to implement a plain packaging scheme, removing branding elements and requiring uniform colors and fonts. The draft regulation faced backlash from tobacco farmers and industries.[143]

Ireland

In May 2013, Ireland announced plans to become the second country in the world to introduce plain cigarette packaging.[144] In June 2014, the Irish government said it would legislate to implement plain packaging. Details of the bill known as the Public Health (Standardised Packaging of Tobacco) Bill 2014 were published on 10 June 2014. "There is a wealth of international evidence on the effects of tobacco packaging in general and on perceptions and reactions to standardised packaging which support the introduction of this measure," Ireland's Health Minister James Reilly said when releasing details of the bill.[145] The bill was signed by President Michael D. Higgins on 10 March 2015. After some delays, it was announced that the law would take effect on 30 September 2017, with the sale of previously-manufactured cigarettes allowed until 30 September 2018.[146]

Israel

On January 8, 2019, the Knesset passed a bill on the restriction on Advertising and Marketing of Tobacco Products that includes provisions for the introduction of plain packaging in the country (Amendment n°7).[147]

A year after, January 8, 2020: full implementation for both manufacturers and retailers.

Jersey

On 30 June 2021, the States of Jersey passed a law requiring plain packaging for tobacco. It stated branded packages could only be brought into Jersey until 1 January 2022 and that branded packaging for cigarettes would be banned from sale on 31 July.[148]

Malaysia

On 24 February 2016, the Malaysian health ministry announced that it is planning to follow Australia's example and introduce plain packaging for tobacco in the near future.[149]

Mauritius

In June 2016 in a health workshop about tobacco control, the Mauritian health minister Anil Gayan publicised that the government was looking to introduce plain packaging in the country in the future.[150] Later in November 2018, the government announced that plain packaging would be introduced on the island-nation in June 2019, making it the first nation in Africa to introduce plain packaging.[151]

On 31 May 2020, to mark the World No Tobacco Day, the Minister of Health and Wellness Kailesh Jagutpal reiterated the decision of the country to introduce plain packaging.[152]

Myanmar

In October 2021, the Ministry of Health of Myanmar issued a regulation (Subordinate Legislation of Union Laws) introducing tobacco plain packaging. This regulation was supposed to enter into force on 10 April 2022, but entry was postponed to 1 January 2023 on April 1, 2022.[153] Retailers will be allowed to sell non-compliant products for another 90 days from that date.[154][155] The measure is postponed again in September 2022; the new entry into force becomes December 31, 2023.[156] It is further postponed twice, the last time until October 21, 2025.[50]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, Paul Blokhuis, serving as State Secretary for Health, Welfare and Sports in the Third Rutte cabinet, presented in November 2018 the Prevention Agreement, an agreement concluded between the government, social organizations and private companies aimed at making Dutch people healthier. One of these measures was the implementation of plain packaging for cigarettes and rolling tobacco, since 1 October 2020 at the production level and 1 October 2021 at the retail level, as well as for cigars and electric cigarettes by 2022.[157][158] This measure is meant to make smoking less attractive to young people in particular.[159][160] The legislation also required supermarkets to hide their smoking materials.[161]

New Zealand

New Zealand requires tobacco products to be standardised in a similar manner to Australian requirements. Legislation and associated regulations to enable standardised packaging of tobacco products came into force on 14 March 2018.[162][163] Distributors were given six weeks to clear old stock and following this retailers were given a further six weeks to dispose of old stock.[162] As a result, only standardised tobacco packaging was permissible after 6 June 2018.

Discussion of the need for standardised packaging (formerly called plain packaging), the passage of the legislation through Parliament, and its subsequent coming into force took six years. In April 2012, following an inquiry by the Māori Affairs Select Committee, Government (on recommendation of the then Associate Minister of Health, Dame Tariana Turia) approved plain packaging in principle, a move that tobacco companies said they would strenuously oppose.[164] From July to October 2012 the Ministry of Health undertook a consultation which attracted over 20,000 submissions (including overseas submissions) from public health groups and also the tobacco industry.[165] In February 2013 Government decided to proceed with legislative change in alignment with Australia. A Bill to require the plain packaging of tobacco products – the Smoke-free Environments (Tobacco Plain Packaging) Amendment Bill[166] – was introduced on 17 December 2013.[167] The Bill had its first reading on 11 February 2014.[167] It was referred to the Health Committee for consideration which reported it back to Parliament with minor amendments on 11 August 2014[167] including a change in title from 'Plain Packaging' to 'Standardised Packaging'. The Bill was stalled due to concern over legal action against the Australian government's plain packaging regime.[168] However, in February 2016, Prime Minister John Key commented that there was now firm legal ground for plain packaging and that the measure could become law by the end of 2016.[169] On 30 June 2016, the Bill was given its second reading[170] with consideration by the Committee of the Whole House on 23 August 2016[171] and the third and final reading on 8 September 2016.[172]

On 31 May 2016, (World No Tobacco Day) the Associate Minister of Health, Peseta Sam Lotu-Iiga, released a consultation document on the detail of standardised packaging requirements.[173] An Order in Council was issued on 6 June 2017, making the Smoke-free Environments Regulations 2017 specifying detailed requirements for the standardised design of tobacco packages and products, and also specifying requirements for new and larger warning messages for tobacco packaging. These Regulations came into force on 14 March 2018 and since 6 June 2018, only standardised packages have been allowed for sale in New Zealand.[174][163]

Norway

In August 2012, it was believed that Norway began considering plain packaging.[175] On 31 May 2016 on World No Tobacco Day, the Health Minister Bent Høie announced the introduction of plain packaging to Norway by 2017. The plain packaging rule applies to snus as well as cigarettes.[176][177] In December 2016, the Norwegian Parliament voted overwhelmingly in favour of implementing standardised packaging for tobacco products.[178] The measure was introduced at the same time as the EU Tobacco Products Directive measures on packaging and labelling, taking effect on 1 July 2017. Retailers were given one year (until 1 July 2018) to transition to the new standardised cigarette packages and smokeless tobacco boxes.[179]

Panama

Since 2017, the National Assembly has discussed draft Law 136 on plain packaging.[180] The bill proposes that the color of the packs be dark matte gray and that the mark be presented in white Arial font, size 20, highlighted in bold. Panama ranks second in having the lowest prevalence in the world of consumption, since only 6.4% of adults in the isthmus smoke.

Philippines

Anti-smoking group New Vois Association of the Philippines favored the introduction of plain cigarette packaging in the Philippines as part of their campaign on the 2016 World No Tobacco Day and urged then-presumptive president Rodrigo Duterte to implement a law to standardize cigarette packs. The Department of Health (DOH), however, is not ready to implement plain cigarette packaging, and rather focus on enforcing graphic health warnings on cigarette packs under the Graphic Health Warning Act of 2014 that took effect in March 2016.[181]

Saudi Arabia

In September 2018, Saudi Arabia made a declaration to the World Trade Organization that it was going to introduce plain packaging in the country.[182] Later in December, the Saudi Food and Drug Authority stated that plain packaging must be used by May 2019.[183] The changes made Saudi Arabia the first state in the Arab world to introduce plain packaging in tobacco products. Retailers were allowed to sell their stock of non-compliant packs until the end of December 2019.

Singapore

On 11 February 2019, the Parliament of Singapore passed an amendment of the Tobacco (Control of Advertisements and Sale) Bill mandating plain packaging on cigarettes, and that graphic health warnings must take up 75% of the packet's surface area.[184][185] The law is in force since 1 July 2020.[186]

Slovenia

On 15 February 2017, the Parliament of Slovenia passed a law for the introduction of plain packaging from 2020.[187]

South Africa

A bill seeking to introduce plain tobacco packaging has been passed by South Africa in 2018.[188] It is supported by local organisations against smoking like the National Council Against Smoking and by the World Health Organization. It is opposed by Japan Tobacco International and the Tobacco Institute of Southern Africa.[189][190]

Spain

In Spain, the Ministry of Health initiated work in April 2024 to introduce plain packaging later in the year, as part of a broader legal framework to reduce the rates of tobacco consumption in the country.[191]

Sweden

In Sweden, the Minister of Health directed the committee examining the implementation of the new EU Tobacco Products Directive (2014/40 / EU) to also consider introducing plain packaging in the country. The committee report, presented in March 2016, concluded that plain packaging would require a change to one of the Basic Laws of Sweden.[192]

Switzerland

On 5 December 2014, Swiss parliamentarian Pierre-Alain Fridez tabled a motion for plain packaging in Switzerland. A few days later, the Federal Council said it was opposed to this, saying such a measure "goes too far".[193]

Thailand

In December 2018, Thailand became the first country in Asia to pass legislation mandating plain packaging by September 2019.[194][195] The new law would also require that the graphic health warning must take 85% of packet's area. Smoking is major problem in Thailand, with half of all middle-aged men smoking.

The law entered into force on 10 September 2019. Retailers could sell their stock of non-compliant cigarettes until 8 December 2019.[196]

Turkey

In September 2011, Bloomberg reported that the Turkish government was working on plain packaging regulations. An Istanbul-based newspaper, Milliyet, reported that under the proposal all branding elements would disappear and cigarettes would come in "numbered black boxes" excluding any imagery other than health warnings.[197] In November 2016, Health Minister Recep Akdağ stated that Turkey will "introduce plain packaging where the brand of cigarettes will almost be invisible and sellers will be obliged to store the cigarettes in closed cases instead of transparent displays" in 2017.[198] From September 2019, Turkey is to introduce plain packaging on tobacco products and will also require the health warnings to cover 85% of the packs.[199] Plans are also afoot to raise the smoking age to 21 in the future. By 5 January 2020, no former package is allowed in the market.

Ukraine

In November 2019, anti-smoking activists in Kyiv including local MP Lada Bulakh of the Servant of the People party announced they were petitioning a parliamentary bill to introduce plain packaging in Ukraine.[200][201]

United Kingdom

In November 2013, the UK Government announced an independent review of cigarette packaging in the UK, amid calls for action to discourage young smokers.[202] Public Health Minister Jane Ellison rejected Labour calls for immediate regulation rather than a review, saying: "It's a year this weekend since the legislation was introduced in Australia. It's the right time to ask people to look at this."

The "Plain Packs Protect" campaign by an alliance of health organisations set out the case for tobacco plain packaging in the UK, as did Cancer Research UK's "The Answer Is Plain" campaign, which was launched soon after the government consultation was announced. Opposing this was the smokers' rights group FOREST, which launched a counter-campaign titled "Hands Off Our Packs".[202]

In March 2015, the House of Commons voted 367–113 in favour of introducing plain cigarette packaging. Plain packaging is required for cigarettes manufactured after 20 May 2016 or sold after 21 May 2017.[203][49]

The UK regulations forbid "logos or promotional images … inserts … discounts … offers … information about nicotine, tar or carbon monoxide … lifestyle or environmental benefits [and] mentions or depictions of taste, smell or the absence thereof", while mandating "drab dark brown coloured packaging", specific package shapes and a specific font (Helvetica 14-point) for brand names.[204]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- New productions: 2019. Former package marketing deadline: January 2020. According to: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2019/03/20190301-5.htm.

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads