The New York Times Book Review

Weekly review of books by ''The New York Times'' From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The New York Times Book Review (NYTBR) is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of The New York Times in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely read book review publications in the industry.[2] The magazine's offices are located near Times Square in New York City.

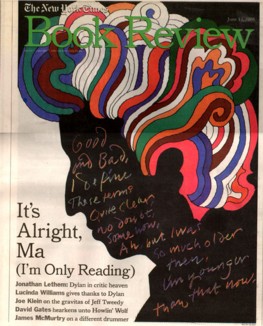

The cover of the June 13, 2004 New York Times Book Review | |

| Editor | Gilbert Cruz[1] |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Weekly |

| First issue | October 10, 1896 |

| Company | The New York Times Company |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City, New York |

| Language | English |

| Website | nytimes |

| ISSN | 0028-7806 |

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

The New York Times has published a book review section since October 10, 1896, announcing: "We begin today the publication of a Supplement which contains reviews of new books ... and other interesting matter ... associated with news of the day."[3] In 1911, the review was moved to Sundays, on the theory that it would be more appreciatively received by readers with a bit of time on their hands.[4]

The target audience is an intelligent, general-interest adult reader.[2] The Times publishes two versions each week, one with a cover price sold via subscription, bookstores and newsstands; the other with no cover price included as an insert in each Sunday edition of the Times (the copies are otherwise identical).

Each week, the NYTBR receives 750 to 1000 books from authors and publishers in the mail, of which 20 to 30 are chosen for review.[2] Books are selected by the "preview editors" who read over 1,500 advance galleys a year.[5] The selection process is based on finding books that are important and notable, as well as discovering new authors whose books stand above the crowd.[2] Self-published books are generally not reviewed as a matter of policy.[2] Books not selected for review are stored in a "discard room" and then sold.[2] As of 2006[update], Barnes & Noble arrived about once a month to purchase the contents of the discard room, and the proceeds are then donated by NYTBR to charities.[2] Books that are actually reviewed are usually donated to the reviewer.[2]

As of 2015, all review critics are freelance; the NYTBR does not have staff critics.[6] In prior years, the NYTBR did have in-house critics, or a mix of in-house and freelance.[2] For freelance critics, they are assigned an in-house "preview editor" who works with them in creating the final review.[2] Freelance critics might be employees of The New York Times whose main duties are in other departments.[6] They also include professional literary critics, novelists, academics and artists who write reviews for the NYTBR on a regular basis.[6]

Other duties on staff include a number of senior editors and a chief editor; a team of copy editors; a letter pages editor who reads letters to the editor; columnists who write weekly columns, such as the "Paperback Row" column; a production editor; a web and Internet publishing division; and other jobs.[2] In addition to the magazine there is an Internet site that offers additional content, including audio interviews with authors, called the "Book Review Podcast".[2]

The book review publishes each week the widely cited and influential New York Times Best Seller list, which is created by the editors of the Times "News Surveys" department.[7]

In 2021, on the 125th anniversary of the Book Review, Parul Sehgal a staff critic and former editor at the Book Review, wrote a review of the NYTBR titled "Reviewing the Book Review".[8]

Pamela Paul was editor from 2013 to 2022, succeeding Sam Tanenhaus,[9] who was editor from 2004 to 2013.

Podcast

"Inside The New York Times Book Review" is the oldest and most popular podcast at The New York Times. The debut episode was released on April 30, 2006 and the show has been recorded weekly ever since.[10]

1983 Legion court case

In 1983, William Peter Blatty sued the New York Times Book Review for failing to include his 1983 novel, Legion, in its best-seller list. The New York Times had previously claimed that it based its "best-seller list" is based on computer-processed sales figures from 2,000 bookstores across the United States. Blatty contended that Legion had sold enough copies to be included on the list. Lawyers for The New York Times did not deny this, but stated that the content of the New York Times best-seller list is editorial in content, and is not an objective compilation of information. The court ruled in favor of The New York Times.[11][12]

Best Books of the Year and Notable Books

Summarize

Perspective

Each year since 1968, around the beginning of December, a list of notable books and/or editor's choice ("Best Books") is announced. Beginning in 2004, it consists of a "100 Notable Books of the Year" list[13] which contains fiction and non-fiction titles, 50 of each. From the list of 100, 10 books are awarded the "Best Books of the Year" title, five each of fiction and non-fiction. Other year-end lists include the Best Illustrated Children's Books, in which 10 books are chosen by a panel of judges.

1990s

|

1998 The Notable Books were announced December 6, 1998.[14] The eleven Editor's Choice books were announced December 6, 1998.[15]

|

1999 The Notable Books were announced December 5, 1999.[16] The eleven Editor's Choice books were announced December 5, 1999.[17]

|

2000s

|

2002 The Notable Books were announced December 8, 2002.[22] The 7 Editor's Choice books were announced December 8, 2002.[23]

|

2003 The Notable Books were announced December 7, 2003.[24] The 9 Editor's Choice books were announced December 7, 2003.[25]

|

|

2004 The 100 Notable Books were announced December 5, 2004.[26] The 10 Best Books were announced December 12, 2004.[27]

|

2005 The 100 Notable Books were announced December 4, 2005.[28] The 10 Best Books were announced December 11, 2005.[29]

|

2010s

2020s

|

2024 The 100 Notable Books were announced November 26, 2024.[66] The 10 Best Books were announced on December 3.[67] Fiction

Nonfiction

|

Studies

In 2010, Stanford professors Alan Sorenson and Jonah Berger published a study examining the effect on book sales from positive or negative reviews in the New York Times Book Review.[68][69] They found all books benefited from positive reviews, while popular or well-known authors were negatively impacted by negative reviews.[68][69] Lesser-known authors benefited from negative reviews; in other words, bad publicity actually boosted book sales.[68][69]

A study published in 2012, by university professor and author Roxane Gay, found that 90 percent of the New York Times book reviews published in 2011 were of books by white authors.[70] Gay said, "The numbers reflect the overall trend in publishing where the majority of books published are written by white writers."[70] At the time of the report, the racial makeup of the United States was 72 percent white, according to the 2010 census (it includes Hispanic and Latino Americans who identify as white).[70]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.