Loading AI tools

2012 graphic novel by American cartoonist Chris Ware From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

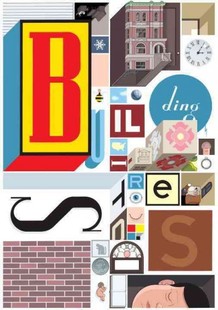

Building Stories is a 2012 graphic novel by American cartoonist Chris Ware. The unconventional work is made up of fourteen printed works—cloth-bound books, newspapers, broadsheets and flip books—packaged in a boxed set. The work took a decade to complete, and was published by Pantheon Books. The intricate, multilayered stories pivot around an unnamed female protagonist with a missing lower leg. It mainly focuses on her time in a three-story brownstone apartment building in Chicago, but also follows her later in her life as a mother. The parts of the work can be read in any order.

| Building Stories | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date | 2012 |

| Page count | 260 pages |

| Publisher | Pantheon Books |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Chris Ware |

| ISBN | 978-0-375-42433-5 |

Ware said he proposed a similar boxed project to Eclipse Comics in 1987, though it was turned down, and had done some smaller-scale single-edition boxed projects while in art school. The boxed version of Building Stories was proposed to Pantheon Books in 2006.[1] The work took a decade to complete, and was published by Pantheon in 2012.[2]

Portions of Building Stories were previously published. Some appeared in Ware's Acme Novelty Library #18 (2007), which itself contained material from The New Yorker, Nest, Kramers Ergot, Chicago Reader, Hangar 21 Magazine, and Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern.[3][4] The story "Touch Sensitive" was originally published in the McSweeney's iPad app in September 2011.[3] The New York Times Magazine ran a seven-month series from 2005-2006 that was reproduced in the box set in the form of a Little Golden Book.[5]

The completed book was published in box form, and is made up of fourteen printed works, including cloth-bound books, newspapers, broadsheets and flip books.[2] The individual pieces are designed to be read in any order,[6] though the inside of the box includes navigational diagrams to assist the reader,[7] with a note that reads "everything you need to know to read the new graphic novel Building Stories".[8] Ware experiments with the book as printed object in a way similar to the experimental French comics collective Oubapo, paying particular attention to the physical aspects of the individual books—the quality of the paper, binding and page dimensions. In a world of disposability and instant communication, Ware states on the reverse of the book that "it's sometimes reassuring—perhaps even necessary—to have something to hold on to". In all, the box contained four broadsheets, three magazines, two strips, two pamphlets, a four-panel storyboard, a hardcover book, and a book designed to mimic the Little Golden Books style.[9]

The protagonist of Building Stories is an unnamed woman[10] with brown hair[2] who suffered the loss of the lower half of her left leg in a childhood boating accident.[3] She comes to inhabit the third floor of a three-story apartment building, with a couple who constantly argue on the second floor and the elderly landlady on the first.[2] The woman sees herself as a failed artist,[7] and the work follows her in the Chicago brownstone[9] apartment building in her twenties. Later in life as a mother,[1] she puts on weight and feels her creativity stifled by domesticity. She still thinks of her first boyfriend, who left her after an abortion, and feels frustrated with her husband.[11]

In the story "Touch Sensitive", people from the future wearing glass helmets peer down on a couple who reside on the building's second floor. They use a technology that can read fragments of memories from an "area's consciousness cloud" and witness the potential breakup of the couple.[3] In the future, the female protagonist, now a mother, tells her child the story of Branford the Best Bee in the World.[2] Branford appears in a stapled pamphlet and a newspaper in the set. After being squashed, he becomes Branford the Benevolent Bacterium.[3] One of the books, resembling a Little Golden Book, charts the happenings in the three-story building on 23 September 2000. There is a large foldout resembling a game board, a Sunday comics-like section, a long, accordion-like foldout section, and other segments difficult to categorize. Some of the stories focus on a single character, such as the thoughts of the landlady, or the story of how the arguing couple met.[2]

The buildings figure prominently in the story. The thoughts of the apartment building in which most of the story takes place are displayed in cursive lettering. The female protagonist is unable to escape the omnipresence of death in the suburban home in Oak Park, Illinois, where had previously lived—her closest college friend commits suicide, her cat dies, she flushes a baby mouse down the toilet, and she is tormented about what to believe about abortion.[3]

Loss is a dominant theme in the work. The characters suffer loss in terms of relationships, romance, finance, weight, and in terms of the main character, loss of limb. The characters fear and resist these losses–though sometimes they desire it.[3] There is much interconnectivity—the smallest details have great importance in the work.[2] There is some self-reflexivity in the book, as when its protagonist comes across a set of Building Stories itself in a bookstore in a dream.[3]

Marcel Duchamp was one of Ware's inspirations, and the box seems partially inspired by Duchamp's Box in a Valise (1935–41), which allowed Duchamp to carry around miniatures of his works.[7]

Aside from the box itself, which has a small quantity of comic panels printed on it, Building Stories contains the following 14 pieces:[12]

Ware makes use of flat, isometric perspective and tiny lettering in rigidly regular square or rectangular panels in his diagrammatic pages.[11] Along with its bright, primary colors and simple, cartoon forms,[9] Ware's graphic style employs symmetrical, repetitive geometrical shapes and motifs, using clear lines and colors. The artwork brings unity to the otherwise messy contents of the project. The cutaway interiors of rooms recall the technique used in domestic scenes by 17th-century Dutch painters, as well as the labeled drawings in the children's storybooks of Richard Scarry. Rather than Scarry's labels, though, the building itself comments on the banalities of life in a careful cursive script.[7]

To mark the publication of Building Stories, The Comics Journal featured a series of articles by the contributors to the 2010 collection of essays The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking.[13] Academic Daniel Worden described Building Stories as "Ware's masterpiece".[3] Academic Martha Kuhlman saw Ware's attempt to "document the multiple perspectives" of the project's characters to aspire "to a graphic novel on the scale of James Joyce's Ulysses.[2] Kuhlman and art historian Roeder find Joseph Cornell's influence in the box's design.[14] Roeder sees Ware's incorporation of the myriad forms of comics from the medium's history as "a miniature pantheon of comic art".[7]

On Book Marks, the book received, based mostly on American publications, "rave" reviews with nine critic reviews and eight being "rave" and one being "positive".[15] On The Omnivore, based on British and American press reviews, the book received an "omniscore" of 4.5 out of 5.[16] The BookScore gave it an aggregated critic score of 8.9/10 based on an accumulation of British and American press reviews.[17]

Building Stories was named as one of the best books of the year by several publications including the New York Times Book Review, Time, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, The Washington Post, Entertainment Weekly, and Amazon.com.[18]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.