List of colonial governors of New Jersey

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

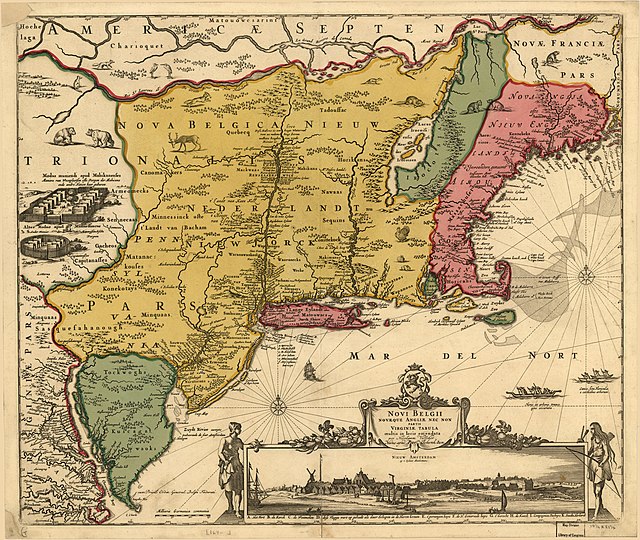

The territory which would later become the state of New Jersey was settled by Dutch and Swedish colonists in the early seventeenth century. In 1664, at the onset of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, English forces under Richard Nicolls ousted the Dutch from control of New Netherland (present-day New York, New Jersey, and Delaware), and the territory was divided into several newly defined English colonies. Despite one brief year when the Dutch retook the colony (1673–74), New Jersey would remain an English possession until the American colonies declared independence in 1776.

In 1664, James, Duke of York (later King James II) divided New Jersey, granting a portion to two men, Sir George Carteret and John Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley of Stratton, who supported the monarchy's cause during the English Civil War (1642–49) and Interregnum (1649–60).[3][4][5] Carteret and Berkeley subsequently sold their interests to two groups of proprietors, thus creating two provinces: East Jersey and the West Jersey.[6] The exact location of the border between West Jersey and East Jersey was often a matter of dispute.[7] The two provinces would be distinct political divisions from 1674 to 1702.

West Jersey was largely a Quaker colony due to the influence of Pennsylvania founder William Penn and its prominent Quaker investors. Many of its early settlers were Quakers who came directly from England, Scotland, and Ireland to escape religious persecution.[8] Although a number of the East Jersey proprietors in England were Quakers and First Governor Robert Barclay of Aberdeenshire Scotland (Ury served by proxy) was a leading Quaker theologian, the Quaker influence on the East Jersey government was insignificant. Many of East Jersey's early settlers came from other colonies in the Western Hemisphere, especially New England, Long Island, and the West Indies. Elizabethtown and Newark in particular had a strong Puritan character.[9][10] East Jersey's Monmouth Tract, south of the Raritan River, was developed primarily by Quakers from Long Island.[11][12]

In 1702, both divisions of New Jersey were reunited as one royal colony by Queen Anne with a royal governor appointed by the Crown.[13] Until 1738, this Province of New Jersey shared its royal governor with the neighboring Province of New York. The Province of New Jersey was governed by appointed governors until 1776. William Franklin, the province's last royal governor before the American Revolution (1775–83), was marginalized in the last year of his tenure, as the province was run de facto by the Provincial Congress of New Jersey. In June 1776, the Provincial Congress formally deposed Franklin and had him arrested, adopted a state constitution, and reorganized the province into an independent state. The constitution granted the vote to all inhabitants who had a certain level of wealth, including single women and blacks (until 1807). The newly formed State of New Jersey elected William Livingston as its first governor on 31 August 1776—a position to which he would be reelected until his death in 1790.[14][15] New Jersey was one of the original Thirteen Colonies, and was the third colony to ratify the constitution forming the United States of America. It thereby was admitted into the new federation as a state on 18 December 1787. On 20 November 1789 New Jersey became the first state to ratify the Bill of Rights.

Before English control

Summarize

Perspective

Directors of New Netherland (1624–64)

New Netherland (Dutch: Nieuw-Nederland) was the seventeenth-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and the Dutch West India Company. It claimed territories along the eastern coast of North America from the Delmarva Peninsula to southwestern Cape Cod. Settled areas of New Netherland now constitute the states of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut as well as parts of Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.[16][17] The provincial capital New Amsterdam was located at the southern tip of the island of Manhattan at Upper New York Bay.[18]

New Netherland was conceived as a private business venture to exploit the North American fur trade.[19] By the 1650s, the colony experienced dramatic growth and became a major port for trade in the North Atlantic. The leader of the Dutch colony was known by the title Director or Director-General. On 27 August 1664, four English frigates commanded by Richard Nicolls sailed into New Amsterdam's harbor and demanded the surrender of New Netherland.[20][21] This event sparked the Second Anglo-Dutch War, which led to the transfer of the territory to England per the Treaty of Breda.[22][23]

| Portrait | Director or Director-General |

Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Cornelius Jacobsen May (fl. 1600s) | 1624 | 1625 |

|

| — | Willem Verhulst (or van der Hulst) (fl. 1600s) | 1625 | 1626 |

|

| Peter Minuit (1580–1638) | 1626 | 1631 |

|

| — | Sebastiaen Jansen Krol (also known as Bastian Krol) (1595–1674) | 1632 | 1633 | — |

| Wouter van Twiller (1606–54) | 1633 | 1638 |

|

| — | Willem Kieft (1597–1647) | 1638 | 1647 |

|

| Peter Stuyvesant (c.1612–72) | 1647 | 1664 |

|

Governors of New Sweden (1638–55)

New Sweden (Swedish: Nya Sverige, Finnish: Uusi-Ruotsi) was a Swedish colony along the Delaware River from 1638 to 1655 that included territory in present-day Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.[31][32] After being dismissed as director of New Netherland by the Dutch West India Company (WIC), Peter Minuit was recruited by Willem Usselincx, Samuel Blommaert and the Swedish government to create the first Swedish colony in the New World.[33] The Swedes sought to expand their influence by creating an agricultural (tobacco) and fur-trading colony, and thus bypassing French and English merchants.[34]: pp.43, 66

The New Sweden Company was chartered and included Swedish, Finnish, Dutch, and German stockholders.[35] Minuit and his company arrived on the Fogel Grip and Kalmar Nyckel at Swedes' Landing (now Wilmington, Delaware) in the spring of 1638.[36] Willem Kieft, Director of New Netherland, objected to the Swedish presence, but Minuit ignored his protests knowing that the Dutch were militarily impotent. The colony would establish Fort Nya Elfsborg, near present-day Salem, New Jersey, in 1643.[34]: pp.70–73.

In May 1654, Swedish militia captured the Fort Casimir, a Dutch defense located near present-day New Castle, Delaware.[37] As a reprisal, the Dutch Director-General Peter Stuyvesant sent an army to the Delaware River, which compelled the surrender of the Swedish forts and settlements in 1655.[34]: pp.155ff The Swedish settlers continued to enjoy local autonomy, retaining their own militia, religion, court, and lands, however, until the English conquest of the New Netherland colony on 24 June 1664.[34]: pp.155ff

| Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter Minuit (1580–1638) | 1638 | 1638 | |

| — | Måns Nilsson Kling (fl. 1600s) | 1638 | 1640 |

|

| — | Peter Hollander Ridder (1608–92) | 1640 | 1643 |

|

| Johan Björnsson Printz (1592–1663) | 1643 | 1653 |

|

| — | Johan Papegoja (d. 1667) | 1653 | 1654 |

|

| — | Johan Classon Risingh (1617–72) | 1654 | 1655 |

|

The New Albion Colony (1634–49)

In 1634, Charles I of England granted a charter to Sir Edmund Plowden, to establish a colony in North America north of lands granted to Lord Baltimore for the Maryland colony in 1633.[41][42] The charter empowered Plowden to assume the title Lord Earl Palatinate, Governor and Captain-General of the Province of New Albion in North America, and poorly defined the boundaries of the New Albion colony.[43] It is believed that the colony would have covered territory within present-day New Jersey, New York, Delaware, and Maryland.[41]

Captain Thomas Young and his nephew, Robert Evelyn, explored and charted the valley of the Delaware River (which they called the Charles River) in the 1630s.[44] Plowden took several years to raise funds, and recruit settlers and "adventurers."[45] In 1642, Plowden and several men sailed from England with aim to settle the colony. This attempt ended in an unsuccessful mutiny, and for the next seven years Plowden remained in Virginia managing the affairs of the intended colony, and selling land rights to adventurers and speculators.[46]

Plowden returned to England in 1649 to raise funds, and promote the colony as a refuge for Roman Catholics exiled during the English Civil War. Despite further attempts to return to his colony, Plowden was confined in a debtors prison and died a pauper in 1659.[46] A notation on John Farrar's 1651 map of Virginia references Plowden's patent for the colony, and labels the Delaware River as "this river the Lord Ployden hath a patten of and calls it New Albion but the Swedes are planted in it and have a great trade of Furrs."[47]

As an English proprietary colony (1664–1702)

Summarize

Perspective

Governors under the Lords Proprietor (1664–73)

With the 1664 surrender of New Netherland by Peter Stuyvesant, and under the authority and instruction of James, Duke of York, Richard Nicolls assumed the position as Deputy-Governor of New Netherland (including Dutch settlements in New Jersey).[48][49]: p.46 His first acts were to guarantee the Dutch colonists their property rights and religious freedom. Nicolls implemented the English common law and a legal code.[49]: pp.43–44 Nicholls would remain governor until 1668, but the Duke of York granted part of the New Netherland territory (that between the Hudson and Delaware rivers, present day New Jersey), to Sir George Carteret and John Berkeley for their devoted service to the Duke of York and his brother Charles II during the English Civil War.[5]

This territory would be called the Province of New Caesaria, or New Jersey after Jersey in the English Channel—one of the last strongholds of the Royalist forces in the English Civil War.[49]: p.60 (see Name of Jersey) As a result of this grant, Carteret and Berkeley became the two English Lords Proprietor of New Jersey. By the 1665 Concession and Agreement, the Lords Proprietor outlined the distribution of power in the province, offered religious freedom to all inhabitants, and established a system of quit-rents, annual fees paid by settlers in return for land.[50] The two Lords Proprietor selected Carteret's brother Philip as the province's first governor.

| Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Richard Nicolls (1624–72) | 1664 | 1665 |

|

| — | Philip Carteret (1639–82) | 1665 | 1672 |

|

| — | John Berry (1635–89/90) | 1672 | 1673 |

|

Restoration of New Netherland (1673–74)

In 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch were able to recapture New Amsterdam (renamed "New York" by the English) under Admiral Cornelis Evertsen the Youngest and Captain Anthony Colve.[53] Evertsen had renamed the city "New Orange".[54] Evertsen returned to the Netherlands in July 1674, and was accused of disobeying his orders. Evertsen had been instructed not to retake New Amsterdam, but instead, to conquer the English and French colonies of Saint Helena and Cayenne (now French Guiana).[55] In 1674, the Dutch agreed to relinquish New Orange to the English in exchange for Suriname under the terms of the Second Treaty of Westminster.[56][57]

| Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Anthony Colve (1644-1693) | 1673 | 1674 |

|

East and West Jerseys (1674–1702)

After the British regained New Jersey and New York, New Jersey was restored as a proprietary colony and was divided into two provinces—East Jersey and West Jersey. In 1674, Berkeley sold his interest in West Jersey to Edward Byllynge and John Fenwick (1618–83). Fenwick rushed to the colony to establish a settlement, Fenwick's Colony, that would become Salem.[59] Due to Byllynge's financial difficulties encountered in his attempts to assert his title to the colony, he sought investment from William Penn, and others. Title issues were settled in 1676 with the negotiation of the Quintipartite Deed between Carteret, Penn, Byllynge, Nicholas Lucas, and Gawen Lawrie dividing the colony into East and West Jersey.[60] West Jersey was largely a Quaker venture focused on the settlement of the lower Delaware River area, and was associated with William Penn and prominent figures in the colonization of the Pennsylvania.[8] After Carteret's death, his heirs sold his interest in East Jersey to twelve investors, eleven of whom were members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), who asked the Quaker apologist Robert Barclay to serve as governor.[61] The settlement of East Jersey, and its commercial and political development was chiefly connected to New England and New York.[9]

This arrangement lasted for approximately thirty years, but because of issues of administration, the proprietors of both colonies surrendered their right to government to Queen Anne. On 17 April 1702, New Jersey was transformed into a crown colony.[13] The proprietors would retain their land rights until the East Jersey proprietors dissolved their corporation (then New Jersey's oldest) in 1998.[62] The West Jersey Proprietors, currently the second oldest corporation in North America, continues as an activity entity based in Burlington, New Jersey.[62][63]

For a brief period beginning in 1688, New York, East Jersey and West Jersey came under the short-lived Dominion of New England.[64] New York and New Jersey were largely overseen by a Lieutenant Governor and army captain, Francis Nicholson.[65] The Proprietors of East Jersey were angered by the revocation of their charters, but retained their property and petitioned Andros, the governor of the dominion, for manorial rights.[66]: p.211 The colony proved too large for a single governor to administer, and Andros was highly unpopular.[66]: pp.180, 192–193, 197

After news of the Glorious Revolution in England reached Boston in 1689, the anti-Catholic Puritans in New England, and Dutch Calvinists in New York launched a revolt against Andros, arresting him and his officers out of fear that Andros sought to impose popery on the colony.[66]: pp.240–250 [67] Leisler's Rebellion in New York City deposed Nicholson in what amounted to an ethnic war between English newcomers and the Dutch who were old settlers.[67] After these events, the colonies reverted to their previous forms of governance until 1702.[66]: pp.212–213

Governors of East Jersey (1674–1702)

| Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Philip Carteret (1639–82) | 1674 | 1682 |

|

| Edmund Andros (1637–1714) | 1674 | 1681 |

|

| — | Robert Barclay (1648–90) | 1682 | 1688 |

|

| Edmund Andros (1637–1714) | 1688 | 1689 |

|

| — | Vacant | 1690 | 1692 |

|

| Andrew Hamilton (d. 1703) | 1692 | 1697 |

|

| — | Jeremiah Basse (d. 1725) | 1698 | 1699 |

|

| Andrew Hamilton (d. 1703) | 1699 | 1702[13] |

|

Governors of West Jersey (1680–1702)

| Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Edward Byllynge (d. 1687) | 1680 | 1687 |

|

| — | Dr. Daniel Coxe (1640–1730) | 1687 | 1688 |

|

| Edmund Andros (1637–1714) | 1688 | 1689 |

|

| — | Dr. Daniel Coxe (1640–1730) | 1689 | 1692 |

|

| Andrew Hamilton (d. 1703) | 1692 | 1697 |

|

| — | Jeremiah Basse (d. 1725) | 1698 | 1699 |

|

| — | Andrew Bowne (c.1638-c.1708) | 1699 | 1699 |

|

| Andrew Hamilton (d. 1703) | 1699 | 1702[13] |

|

As a British Crown colony (1702–76)

Summarize

Perspective

Governors of New York and New Jersey (1702–38)

Shortly after ascending to the British throne, Queen Anne (1665–1714) reunited East Jersey and West Jersey as a royal colony and appointed her cousin Edward Hyde, Viscount Cornbury, as the province's first Royal Governor.[83] In 1702, the governments of the two proprietary colonies had surrendered their authority to the Crown which reorganized New Jersey into a crown colony with a government that consisted of a governor and twelve-member council appointed by the British monarch, and a twenty-four-member assembly whose members were elected by colonists who were qualified to vote by owning at least 1,000 acres of land.[13]

For the next four decades, New Jersey and New York shared one royal governor. Because the crown's representatives were generally incompetent or corrupt, and the royal governor often ignored New Jersey and its affairs, the colonists had substantial autonomy, and the proprietors continued to wield considerable power through the retained control of land titles and sales. The relationship between many of the Royal Governors and the provincial assembly was often hostile. The assembly would simply respond to disagreements over legislation by using its appropriation power to withhold the governor's salary. Several historians point towards a factionalism which defined the colonial government, but the factions have been described as inchoate and characterized by shifting alliances between the colony's various ethnic, religious, proprietary, and landowning groups.[84]

During this period, the population of the colony began to expand, from 14,000 in 1700 to nearly 52,000 by 1740.[85] It was a diverse colony, as Queen Anne and Royal Governor Hunter began to important Palatine Germans into New York's Hudson Valley in a plan to produce naval stores. Many of these German families eventually settled in New Jersey.[86] West Jersey's colonists included Irish, English, Welsh and Scottish Quakers and the descendants of Swedish and Finnish colonists from the former New Sweden colony. Dutch and Huguenot families from New York settled in the valleys of the Raritan River and Hackensack River, and in the northwestern New Jersey's Minisink region.[87][88][89] New Englanders from Connecticut and Long Island, and English planters from Barbados arrived with African slaves.[90]: p.39 Because of its liberal grant of religious freedom, the colony's diversity was also reflected in its religious plurality, with a strong presence of Dutch Reformed, Lutheran, Huguenot, Quaker, Puritan, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Anglican churches.[90]: p.39

| No. | Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury (1661–1723) | 1701 | 1708 |

|

| 2 | — | John Lovelace, 4th Baron Lovelace (1672–1709) | 1708 | 1709 |

|

| — | — | Richard Ingoldesby (d. 1719) | 1709 | 1710 |

|

| 3 |  | Robert Hunter (1664–1734) | 1710 | 1720 |

|

| 4 |  | William Burnet (1687/88–1729) | 1720 | 1728 |

|

| 5 | — | Colonel John Montgomerie (d. 1731) | 1728 | 1731 |

|

| — |  | Lewis Morris (1671–1746) | 1731 | 1732 |

|

| 6 |  | Sir William Cosby (1690–1736) | 1732 | 1736 |

|

| — | — | John Anderson (1665–1736) | 1736 | 1736 |

|

| — | — | John Hamilton | 1736 | 1738 |

|

| 7 | — | John West, 1st Earl De La Warr (1693–1766) | 1737 | 1737 |

|

Governors of New Jersey (1738–76)

After tensions were provoked with the Penn's Walking Purchase in 1737, relations between colonists and the region's Native American tribes became increasingly hostile.[104][105] During these years, colonists left the seacoast cities and settled the colony's northwestern wilderness. Much of the provincial government's actions during this time was organizing the wilderness into townships often named after English and colonial political figures. By the 1750s, violent raids against these settlers, and fears that the French were supporting these hostilities led to the French and Indian War.[106]

During this time, the colonial government provided generous monetary rewards to colonists who killed Indians, established a line of fortifications in the Minisink (i.e., the upper valley of the Delaware River), and mustered military units (the New Jersey Frontier Guard and 1st New Jersey Regiment) to defend this frontier and carry out punitive raids on Indian villages.[106][107] Hostilities began to subside with the Treaty of Easton in October 1758, negotiated by New Jersey Royal Governor Francis Bernard, Pennsylvania Attorney-General Benjamin Chew, and chiefs of 13 Native American nations, led by Teedyuscung.[105]: pp.102–123

New Jersey was the only province to have two colleges established during the colonial period, and the colony's governors were influential in their establishment.[108][109] Governors John Hamilton, John Reading, and Jonathan Belcher aided the establishment of The College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) which was founded in 1746 in Elizabethtown by a group of Great Awakening "New Lighters" that included Jonathan Dickinson, Aaron Burr, Sr. and Peter Van Brugh Livingston.[110][111] In 1756, the school moved to Princeton.[112][113] In 1766, Governor William Franklin issued the charters to establish Queens College (now Rutgers University) in New Brunswick to "educate the youth in language, liberal, the divinity, and useful arts and sciences" and for the training of future ministers for the Dutch Reformed Church. Franklin issued a second charter in 1770 after the college's trustees requested amendments.[114][115][116]

In the last year of William Franklin's tenure, his power was diminished and he became marginalized by the rebellious sentiment rising in the colony's residents. The province was being run de facto by the Provincial Congress of New Jersey (1775–76). While colonial militia had put Franklin under house arrest in January 1776, he would not be formally deposed until June 1776 when the colony's Provincial Congress had him imprisoned. Franklin considered the Provincial Congress to be an "illegal assembly."[117] Under the direction of its president Samuel Tucker (1721–89), the Provincial Congress proceeded to adopt a state constitution and reorganize the province into an independent state.[118] The newly formed State of New Jersey elected William Livingston as its first governor on 31 August 1776.[119][120]

| No. | Portrait | Governor | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 |  | Lewis Morris (1671–1746) | 1738 | 1746 |

|

| — | — | John Hamilton | 1746 | 1747 |

|

| — | — | John Reading (1686–1767) | 1747 | 1747 |

|

| 9 |  | Jonathan Belcher (1681/2–1757) | 1747 | 1757 |

|

| — | — | John Reading (1686–1767) | 1757 | 1758 |

|

| 10 |  | Francis Bernard (1712–79) | 1758 | 1760 |

|

| 11 | — | Thomas Boone (c.1730–1812) | 1760 | 1761 | |

| 12 | — | Josiah Hardy (1715–90) | 1761 | 1763 |

|

| 13 |  | William Franklin (c.1730–1814) | 1763 | 1776 |

|

See also

- For post-independence governors (1776–present), see List of governors of New Jersey.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.