Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Jersey City, New Jersey

City in Hudson County, New Jersey, US From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

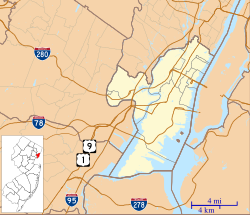

Jersey City is the second-most populous[30] city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.[31] It is the county seat of Hudson County[32] and is the county's most populous city[21] and its largest by area.[10] As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 292,449,[20][21] an increase of 44,852 (+18.1%) from the 2010 census count of 247,597,[33][34] in turn an increase of 7,542 (+3.1%) from the 240,055 enumerated at the 2000 census.[35][36] The Population Estimates Program calculated a population of 302,284 for 2024, making it the 70th-most populous municipality in the nation.[22] With more than 40 languages spoken in more than 52% of homes and as of 2020, 42.5% of residents born outside the United States, it is the most ethnically diverse city in the United States.[37]

Remove ads

The third most-populous city in the New York metropolitan area, Jersey City is bounded on the east by the Hudson River and Upper New York Bay and on the west by the Hackensack River and Newark Bay. A port of entry, with 30.7 miles (49.4 km) of waterfront and extensive rail infrastructure and connectivity,[38] the city is an important transportation terminus and distribution and manufacturing center for the Port of New York and New Jersey with Port Jersey as the city's intermodal freight transport facility and container shipping terminal. The Holland Tunnel, PATH rapid transit system, and NY Waterway ferry service connect across the Hudson River with Manhattan.[39][40]

The area was settled by the Dutch in the 17th century as Pavonia and later established as Bergen; the first permanent settlement, local civil government and oldest municipality in what became the state of New Jersey. The area came under English control in 1664. Jersey City was incorporated in 1838 and annexed Van Vorst Township in 1851. On May 3, 1870, following a special election in 1869 with a majority of county support, Jersey City annexed Bergen City and Hudson City to form "Greater Jersey City" with Greenville joining in 1873.[41] Jersey City grew into a busy port city on New York Harbor by the late 19th and early 20th century. Jersey City's official motto, displayed on the city seal and flag, is "Let Jersey Prosper" referencing its 19th century border dispute with New York City.

Jersey City is home to several institutions of higher education such as New Jersey City University, Saint Peter's University and Hudson County Community College. As the county seat, Jersey City is home to the Hudson County Courthouse and Frank J. Guarini Justice Complex. Cultural venues throughout the city include the Loew's Jersey Theatre, White Eagle Hall, the Liberty Science Center, Ellis Island, Mana Contemporary and the Museum of Jersey City History. Large parks in Jersey City are Liberty State Park, Lincoln Park and Berry Lane Park. Redevelopment of the Jersey City waterfront has made the city one of the largest hubs for banking and finance in the United States and has led to the district and city being nicknamed Wall Street West.[42] Since the 1990s, Jersey City has been a destination for artists and hipsters.[43] With the city's proximity and connections to Manhattan, its growing arts, culture, culinary and nightlife scene and its own finance and tech based economy, apartment rents in the city have grown to become some of the highest in the United States.[44][45] In response, Jersey City has instituted zoning and legislation to require developers to include affordable housing units in their developments.[46] In 2023, Travel + Leisure ranked Jersey City as the best place to live in New Jersey.[47]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Lenape and New Netherland

The land that is now Jersey City was inhabited by the Lenape, a collection of Native American tribes (later called Delaware Indian). In 1609, Henry Hudson, seeking an alternate route to East Asia on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, anchored his small vessel Halve Maen (English: Half Moon) at Sandy Hook, Harsimus Cove and Weehawken Cove, and elsewhere along what was later named the North River. After spending nine days surveying the area and meeting its inhabitants, he sailed as far north as Albany and later claimed the region for the Netherlands. The contemporary flag of the city is a variation on the Prince's Flag from the Netherlands. The stripes are blue, white and yellow, with the center of the flag showing the city seal, depicting Hudson's ship, the Half Moon, and other modern vessels.[48]

By 1621, the Dutch West India Company was organized to manage this new territory and in June 1623, New Netherland became a Dutch province, with headquarters in New Amsterdam. Michael Reyniersz Pauw received a land grant as patroon on the condition that he would establish a settlement of not fewer than fifty persons within four years. He chose the west bank of the Hudson River and purchased the land from the Lenape for 80 fathoms (146 m) of wampum, 20 fathoms (37 m) of cloth, 12 kettles, six guns, two blankets, one double kettle, and half a barrel of beer. This grant is dated November 22, 1630, and is the earliest known conveyance for what are now Hoboken and Jersey City. Pauw, however, was an absentee landlord who neglected to populate the area and was obliged to sell his holdings back to the Company in 1633.[49] That year, a house was built at Communipaw for Jan Evertsen Bout, superintendent of the colony, which had been named Pavonia (the Latinized form of Pauw's name, which means "peacock" or "land of the peacock").[50][51] Shortly after, another house was built at Harsimus Cove in 1634 and became the home of Cornelius Henrick Van Vorst, who had succeeded Bout as superintendent, and whose family would become influential in the development of the city.[52] Relations with the Lenape deteriorated, in part because Director-General Willem Kieft attempted to tax and drive out the Lenapes, which led to a series of raids and reprisals and the virtual destruction of the settlement on the west bank. During Kieft's War, approximately 120 Lenapes were killed by the Dutch in a massacre ordered by Kieft at Pavonia on the night of February 25, 1643.[53] On May 11, 1647, Peter Stuyvesant arrived in New Amsterdam to replace Kieft as Director-General of New Netherland. On September 15, 1655, Pavonia was attacked as part of a Munsee occupation of New Amsterdam called the Peach War that saw 40 colonists killed and over 100, mostly women and children, taken captive and held at Paulus Hook. They were later ransomed to New Amsterdam.

On January 10, 1658, Stuyvesant "re-purchased" the scattered communities of farmsteads that characterized the Dutch settlements of Pavonia: Communipaw, Harsimus, Paulus Hook, Hoebuck, Awiehaken, Pamrapo, and other lands "behind Kill van Kull". The village of Bergen (located inside a palisaded garrison) was established by the settlers who wished to return to the west bank of the Hudson on what is now Bergen Square in 1660, the first town square in North America, and officially chartered by Stuyvesant on September 5, 1661, as the state's first local civil government. The village was designed by Jacques Cortelyou, the first surveyor of New Amsterdam.[54] The word berg taken from the Dutch means "hill", while bergen means "place of safety".[55] The charter partially removed Bergen from the jurisdiction of New Amsterdam and put the surrounding settlements under its authority. As a result, it is regarded as the first permanent settlement and oldest municipality in what would become the state of New Jersey.[56][57] It is also the home of Public School No. 11, the nation's longest-continuous school site and the site of the first free and public school building in New Jersey,[58] and Old Bergen Church, the oldest continuous congregation in New Jersey. In addition, the oldest surviving houses in Jersey City are of Dutch origin including the Newkirk House (1690),[59] the Van Vorst Farmhouse (1740),[60][61][62] and the Van Wagenen House (1740).[63][64]

In 1661, Communipaw Ferry began operation as the first ferry service between the village of Communipaw (Jersey City) and New Amsterdam (Manhattan) shortly after the village of Bergen was established.[65]

Province of New Jersey

On August 27, 1664, four English frigates sailed into New York Harbor and captured Fort Amsterdam, and by extension, all of New Netherland, a prelude to the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Under the Articles of Capitulation, the Dutch residents of Bergen were allowed to continue their way of life and worship. Later in 1664, James, the Duke of York, granted the land between the Hudson and Delaware River to Sir George Carteret as a debt settlement. Carteret named the land New Jersey after his homeland the island of Jersey. The Concession and Agreement was issued soon after providing religious freedom and recognition of private property in the colony.[66] In exchange, residents were required to pledge loyalty to their new government.[67]

Following the Treaty of Westminster, New Jersey split into East Jersey and West Jersey. From 1674 to 1702, Bergen was part of East Jersey and became a town in Bergen County on March 7, 1683, one of the four newly independent counties in East Jersey. In 1702, New Jersey was reunified and became a royal colony. Bergen was chosen as the county seat in 1710 and was re-established by royal charter on January 4, 1714.[68]

18th century

By the 1760s, Paulus Hook was known for its convenient stagecoach and ferry services. In 1764, Cornelius Van Vorst (1728–1818) established the Paulus Hook Ferry (later called "Jersey City Ferry")[69] and operated the service from Paulus Hook to Cortlandt Street.[70] To further attract patrons to his ferry landing, Van Vorst created a mile-long circular horse racing track that attracted tourists from both sides of the Hudson and built the Van Vorst Tavern near Grand and Hudson Streets as a one-story building with a Dutch roof and eaves and an overhanging porch that faced the river. To further ensure the profitability of his business ventures on the small island of Paulus Hook, he created an embankment road above the tidal marshes to the mainland. Ahead of the Revolutionary War, Van Vorst declared himself a patriot and in 1774 was appointed to one of the committees of correspondence, representing Bergen County and attended a meeting in New Brunswick to elect delegates to the Second Continental Congress.[71]

American Revolution

In 1776, even before the war, General George Washington ordered American patriots to construct several forts to defend the western banks of the Hudson River, one of which was located at Paulus Hook. The fort was a naturally defensible position that guarded New York from British attack, guarded the Hudson River channel and the gateway to New Jersey. After suffering defeats in New York City, on September 23, 1776, the American patriots abandoned Paulus Hook, leaving the fort to become the first New Jersey territory invaded and occupied by the British.

In mid-summer 1779, a 23-year-old Princeton University graduate, Major Henry Lee, recommended to General Washington a daring plan for the Continental Army to attack the fort, in what became known as the Battle of Paulus Hook. The assault was planned to begin shortly after midnight on August 19, 1779. Lee led a force of about 300 men, some of whom got lost during the march through the swampy, marshy land. The attack was late to start but the main contingent of the force was able to reach the fort's gate without being challenged. It is believed that the British mistook the approaching force for allied Hessians returning from patrol, though this has not been definitively documented.

The attacking Patriots succeeded in damaging the fort and took 158 British prisoners, but were unable to destroy the fort and spike its cannons.[72] As daytime approached, Lee decided the prudent action was to have his Patriots withdraw before British forces from New York could cross the river. Paulus Hook remained in British hands until after the war but the battle was a small strategic victory for the forces of independence as it forced the British to abandon their plans for taking additional rebel positions in the New York area.

Later that August, General Washington met with the Marquis de Lafayette in the village of Bergen to discuss war strategy over lunch and to bait the British into attacking Bergen from New York. The meeting purportedly took place at the Van Wagenen House on Academy Street. Additionally, a nearby "point of rocks" at the east end of the street provided an ideal vantage point for military surveillance of the Hudson River.[73]

One day in September 1780, a local Bergen farmer, Jane Tuers, was selling her goods in British-occupied Manhattan when she stopped in Fraunces Tavern and spoke with the owner, Samuel Fraunces. He informed Tuers that British soldiers were in his tavern toasting General Benedict Arnold, who was to deliver West Point to the British. Tuers returned to Bergen later that day and informed her brother Daniel Van Reypen about the conspiracy. Van Reypen, a staunch patriot, rode to Hackensack to meet with General Anthony Wayne who then sent Van Reypen to inform General Washington of the conspiracy. The information provided by Tuers confirmed what Washington had suspected of Arnold and led to the arrest, trial, conviction and hanging of co-conspirator John André for treason and stopped the plot to surrender West Point. Arnold would later defect to the British to escape prosecution.[74]

On November 22, 1783, the British evacuated Paulus Hook and sailed home[75] three days before they left New York on Evacuation Day. While these events occupy a small portion of U.S. Revolutionary War history, they are important events in the history of New Jersey and New Jersey's role in the American Revolution and hold an even greater significance in the history of the local neighborhoods. In 1903, an obelisk was erected at Paulus Hook Park at the intersection of Washington and Grand Streets, the site of the fort, to memorialize the Battle of Paulus Hook. In 1924, a plaque honoring Jane Tuer's heroism was installed at the site of her former home now Hudson Catholic Regional High School. In 2021, the restored Van Wagenen House was re-opened as the Museum of Jersey City History.[76][74]

On February 21, 1798, Bergen became a township by the New Jersey Legislature's Township Act of 1798 as the first group of 104 townships in New Jersey.[68]

19th century

In 1804, Alexander Hamilton, now a private citizen, was focused on increasing manufacturing in the greater New York City area. To that end, he helped to create the "Associates of the Jersey Company" which would lay the groundwork for modern Jersey City through private development. While envisioning the future of Jersey City, Hamilton said: "One day, a great city shall rise on the western banks of the Hudson River."[77][78] The consortium of 35 investors behind the company were predominantly Federalists who, like Hamilton, had been swept out of power in the election of 1800 by Thomas Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans. Large tracts of land in Paulus Hook were purchased by the company with the titles owned by Anthony Dey, who was from a prominent old Dutch family, and his two cousins, Colonel Richard Varick, the former mayor of New York City (1789–1801), and Jacob Radcliff, a Justice of the New York Supreme Court who would later become mayor of New York City (twice) from 1810 to 1811 and again from 1815 to 1818. They laid out the city squares and streets that still characterize the neighborhood, giving them names also seen in Lower Manhattan or after war heroes (Grove, Varick, Mercer, Wayne, Monmouth and Montgomery among them).[79] John B. Coles, a former New York State senator (1799–1802), purchased the area north of Paulus Hook known as Harsimus and laid out a grid plan centered around a park. Following Hamilton's death, Coles proposed naming the park in his honor as "Hamilton Park".[80]

Despite Hamilton's untimely death in July 1804, the Association carried on with the New Jersey Legislature approving Hamilton's charter of incorporation on November 10, 1804. However, the enterprise was mired in a legal boundary dispute between New York City and the state of New Jersey over who owned the waterfront. This along with the associated press coverage discouraged investors who wanted lots on the waterfront for commercial purposes. The unresolved dispute would continue until the Treaty of 1834 where New York City formally ceded control of the Jersey City waterfront to New Jersey. Over that time though, the Jersey Company opened the city's first medical facility, known as the "pest house", in 1808[81] and applied to the New Jersey Legislature to incorporate the "Town of Jersey" in 1819. The legislature enacted "An Act to incorporate the City of Jersey, in the County of Bergen" on January 28, 1820. Under the provision, five freeholders (including Varick, Dey, and Radcliff) were to be chosen as "the Board of Selectmen of Jersey City", thereby establishing the first governing body of the emerging municipality. The city was reincorporated on January 23, 1829, and again on February 22, 1838, at which time it became completely independent of Bergen and was given its present name. On February 22, 1840, Jersey City became part of the newly created Hudson County which separated from Bergen County and annexed the former Essex County land of New Barbadoes Neck.[68]

In 1812, Robert Fulton began steam ferry service via "The Jersey" between Paulus Hook and Manhattan, eight years after building a shipyard at Greene and Morgan Streets.[82][83] In 1834, the New Jersey Rail Road and Transportation Company opened the city's first rail line from Jersey City Ferry to Newark. From 1834 to 1836, the Morris Canal was extended from Newark to Jersey City and New York Harbor linking the Delaware River with the Hudson River. This extension connected Jersey City to Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley and New Jersey's interior providing a steady and easy supply of coal and anthracite pig iron for the growing iron industry and other developing industries adopting steam power in Jersey City and the region.

In 1839, Provident Savings Institution was charted by the state as the first mutual savings bank in New Jersey and the first bank in Jersey City and Hudson County. Co-founded by the city's first mayor, Dudley S. Gregory (1838–1840), in the wake of the Panic of 1837, there was a general mistrust of banks by the public. In response, the bank's charter established it as a "mutual savings bank" to assist the city's immigrant poor. In 1891, the bank headquarters became the temporary home of the first branch of the Jersey City Free Public Library until the Main Library branch opened in 1901.[84][85]

On April 12, 1841, the New Jersey Legislature incorporated Van Vorst Township from portions of Bergen. Land was donated by the Van Vorst family for a town square style park that became Van Vorst Park. The township was later annexed by Jersey City on March 18, 1851.[86] From 1854 to 1874, the kitchen step of the Van Vorst Mansion, home of former mayor Cornelius Van Vorst (1860–1862), was known to be the slab of marble that was originally the base of the statue of King George III that was toppled by the Sons of Liberty at Bowling Green in Lower Manhattan in 1776.[87][88] Van Vorst also constructed the neighboring Barrow Mansion where his sister Eliza lived.

By mid century, Jersey City's rapidly urbanizing population began to encounter significant challenges gaining access to freshwater. In 1850, Jersey City Water Works engineer William S. Whitwell, proposed a three-reservoir complex in the Jersey City Heights (then part of North Bergen) connected to a pumping station near the Passaic River in Belleville by a massive underground aqueduct to deliver freshwater to the city. Reservoir No. 1 was built between 1851 and 1854 and Reservoir No. 3 was built between 1871 and 1874 under the direction of engineer John Culver. Reservoir No. 2 was never constructed and later became Pershing Field.[89]

During the 19th century, former slaves reached Jersey City on one of the four main routes of the Underground Railroad that all converged in the city. On Bergen Hill, the Hilton-Holden House, named after noted abolitionist and astronomer David Le Cain Holden, was a "station" for fugitive slaves to stop over and seek refuge and is one of the last remaining in the city.[90] Slaves would then be hidden in wagons en route to the Jersey City waterfront and Morris Canal Basin where abolitionists would hire ferry and coal boats to transport former slaves up to Canada or New England to freedom.[91][92]

In 1868, the Jersey City Board of Alderman took over the pest house and renamed it "Jersey City Charity Hospital" and operated it as a public medical facility, the first in the city and state, where physicians provided free medical care to city residents. In 1885, the hospital expanded to a new 200-bed facility on Bergen Hill to remove the hospital from the increasing industrial development at Paulus Hook.[81]

Consolidation of Jersey City

Soon after the Civil War, the idea arose of uniting all of the towns of Hudson County east of the Hackensack River into one municipality. In 1868, a bill for submitting the question of consolidation of all of Hudson County to the voters was presented to the Board of Chosen Freeholders (now known as the Board of County Commissioners). The bill was approved by the state legislature on April 2, 1869, with a special election to be held on October 5, 1869. An element of the bill provide that only contiguous towns could be consolidated. While a majority of the voters across the county approved the merger, the only municipalities that had approved the consolidation plan and that adjoined Jersey City were Hudson City and Bergen City.[93] The consolidation began on March 17, 1870, taking effect on May 3, 1870.[94] Three years later the present outline of Jersey City was completed when Greenville agreed to merge into the Greater Jersey City.[68][95]

Following consolidation, the city's first university, Saint Peter's College, was charted in 1872 and classes began on September 2, 1878, in Paulus Hook. Decades later, it would adopt the peacock as its mascot in partial reference to the original settling of the Jersey City area as "Pavonia", land of the peacock.[96]

On October 28, 1886, the Statue of Liberty was dedicated by President Grover Cleveland just off the city's shores at Bedloe's Island in New York Harbor. The statue would welcome millions of immigrants as they arrived by ship at Ellis Island (opened in 1892) in the coming decades.

By the late 1880s, three passenger railroad terminals opened in Jersey City along the Hudson River (Pavonia Terminal,[97] Exchange Place and Communipaw) making Jersey City a terminus for the nation's rail network.[98][99][77] Tens of millions, roughly two-thirds, of immigrants that were processed at Ellis Island entered the United States through Communipaw Terminal to then settle in Jersey City and its neighboring municipalities or make their way westward.[98][100] The railroads transformed the geography of the city by building several tunnels and cuts, such as the Bergen Arches, through the city and filling in the coves at Harsimus and Communipaw for the construction of several large freight rail yards along the waterfront.[101][102][103]

Jersey City became an important port, railroad and manufacturing city during the 19th and 20th centuries. Much like New York City, Jersey City has always been a destination for new immigrants to the United States. German, Russian, Polish, Scottish, Irish and Italian immigrants settled in local tenements and found work at the local docks, railroads and adjacent companies such as American Can, Colgate, Chloro, Lorillard Tobacoo and Dixon Ticonderoga.[104] During this time, concern grew for the social issues of the city's immigrant poor. Cornelia Foster Bradford founded Whittier House in Paulus Hook in 1894 as the first "settlement house" in New Jersey. Whittier House led to several social reforms and city "firsts" such as free kindergarten, a dental clinic, a visiting nurse service, a milk and medical dispensary, diet kitchen for mothers and babies and a playground. Mary Buell Sayles, a settlement resident, wrote The Housing Conditions of Jersey City in 1902 about the lives of immigrants in and around Paulus Hook. In response, mayor Mark M. Fagan (1902–1907) created the Municipal Sanitary League and opened the city's first public bath house on Coles Street in 1904. That same year, the first "State Tenement House Commission" was formed and the New Jersey Legislature passed the "Tenement House Act".[105][106][107]

20th century

By the turn of the 20th century, the City Beautiful movement had spread throughout cities in the United States. Part of its mission was to preserve public space for recreational activities in urban industrial communities. The Hudson County Parks Commission was created in 1892 to plan and develop a county wide park and boulevard system similar to those found in other cities. From 1892 to 1897, Hudson Boulevard (now John F. Kennedy Boulevard) was built to connect the future park system from Bayonne to North Bergen through Jersey City.[108][109][110] In 1905, Lincoln Park opened on the city's West Side as the largest park in Jersey City and the first and largest park in the county system. Designed by Daniel W. Langton and Charles N. Lowrie, the 273.4 acres (110.6 ha) park was mostly built on undeveloped wetlands and woodlands known as "Glendale Woods", stretching from the Boulevard to the Hackensack River.[111] The Jersey City government was also inspired by the City Beautiful movement to build more open space creating Dr. Leonard J. Gordon Park in the Heights along Hudson Boulevard, Mary Benson Park in Downtown and Bayside Park in Greenville.[112] The movement also inspired the construction of grand civic buildings in the city such as City Hall and the Hudson County Courthouse.[77]

In 1908, the city's water supply was the first permanent chlorinated disinfection system for drinking water in the United States. Devised by John L. Leal and designed by George W. Fuller, the system was installed at the city's new Boonton Reservoir, which replaced the Passaic River as the city's freshwater source in 1904.[113] The Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (now the PATH system) opened between 1908 and 1913 as New Jersey's first underground rapid transit system. For the first time, Jersey City and the rail terminals at Hoboken, Pavonia and Exchange Place were directly linked with Midtown and Lower Manhattan under the Hudson River, providing an alternative to transferring to the extensive ferry system.

In 1910, William L. Dickinson High School opened as the first purpose-built high school in Jersey City. The design of the school, built during the City Beautiful movement, is thought to have been inspired by that of the Louvre Colonnade and Buckingham Palace. The prominent hilltop location of the school has been an important location throughout the city's history. During the Revolutionary War, it was used as a lookout by General Washington and Marquis de Lafayette to observe British movements at the forts at Paulus Hook and in Lower Manhattan. After the start of the War of 1812, the site assisted in defending New York Harbor with an arsenal built on the property's west side and with the east side serving as a troop campground. During the Civil War, the arsenal served as barracks for Union soldiers and a hospital. The school was used as an army training facility during World War I and World War II.[114][115]

On July 30, 1916, the Black Tom explosion occurred killing 7 people, damaging the Statue of Liberty and causing millions of dollars in damage in Jersey City and throughout the New York metropolitan area. The explosion was an act of sabotage on American munitions by German spies of the Office of Naval Intelligence to prevent the ammunition from being shipped to the Allies for use during World War I. This event, coupled with the torpedoing of the RMS Lusitania, which killed 136 Americans in 1915, pushed the United States into entering the War in 1917.[116][77]

Mayor "Boss" Hague

From 1917 to 1947, Jersey City was governed by Mayor Frank Hague. Originally elected as a candidate supporting reform in governance, his name is "synonymous with the early twentieth century urban American blend of political favoritism and social welfare known as bossism".[117] Hague ran the city with an iron fist while, at the same time, molding governors, United States senators, and judges to his whims while also being a close political ally to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Boss Hague was known to be loud and vulgar, but dressed in a stylish manner, earning him the nickname "King Hanky-Panky".[118] In his later years in office, Hague would often dismiss his enemies as "reds" or "commies". Hague lived like a millionaire, despite having an annual salary that never exceeded $8,500. He was able to maintain a fourteen-room duplex apartment in Jersey City, a suite at the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan, and a palatial summer home in the Jersey Shore community of Deal, and travel to Europe yearly in the royal suites of the best ocean liners.[119][120]

Hague's time as mayor was also marked by his direct influence in the construction of several important infrastructure, educational, open space, healthcare and public works projects that became functional civic landmarks that define the city to this day. Some of these projects are the construction of Journal Square and its theaters, the Holland Tunnel, the Wittpenn Bridge, the design of New Jersey Route 139, the Pulaski Skyway, Lincoln High School, Snyder High School, A. Harry Moore School, New Jersey City University, the Heights, Miller and Greenville branches of the library system, Pershing Field, Audubon Park, five public housing complexes, Harborside Terminal, the Seventh Police Precinct and Criminal Court, the expansion of Jersey City Hospital to Jersey City Medical Center, the Jersey City Armory and Roosevelt Stadium.[121] Hague financed several of these projects with WPA funds secured by congresswoman Mary Teresa Norton (1925–1951), the first woman elected to represent New Jersey or any state in the Northeast.[120]

After Hague's retirement from politics, a series of mayors including John V. Kenny, Thomas J. Whelan and Thomas F. X. Smith attempted to take control of Hague's organization, usually under the mantle of political reform. None were able to duplicate the level of power held by Hague,[122] but the city and Hudson County remained notorious for political corruption for decades to come.[123][124][125]

Post-World War II

Following World War II, returning veterans created a post-war economic boom and were beginning to buy homes in the suburbs with the assistance of the G.I. Bill. During the Great Depression and the war years, not much new housing was constructed, leaving cities with older and overcrowded housing stock. In response, Jersey City looked to build new housing on undeveloped tracts around the city. College Towers was built on the West Side as the first middle-income housing cooperative apartment complex in New Jersey in 1956. Country Village was built in the 1960s as a middle-income "suburbia-in-the-city" planned community in the Greenville/West Side area to offer the "out of town" experience without leaving the city. The city had hoped that new residential neighborhoods and housing stock would keep the city's population stable.[126][127]

In 1951, Seton Hall University School of Law opened on the site of the former John Marshall Law School at 40 Journal Square and would relocate to Newark by the end of the year.[128] From 1956 to 1968, Jersey City Medical Center was the home of the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry, the predecessor to the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ), which would relocate to Newark in 1969.[129]

In 1956, the Newark Bay (Hudson County) Extension (I-78) of the New Jersey Turnpike opened. As the first limited-access section of I-78 to be built in the state, the extension connected Jersey City and the Holland Tunnel to the mainline of the Turnpike in Newark via the Newark Bay Bridge and at an estimated cost of $2,765 per foot, it was deemed the "world's most expensive road".[130] That same year, the standard shipping container debuted along with the maiden voyage of the container ship SS Ideal X from Port Newark to the Port of Houston. These innovations changed forever the way the maritime industry shipped goods by sea and led to the transformation of Port Newark into the leading container port in New York Harbor. As a result, the Jersey City waterfront, along with the other traditional waterfront port facilities in the harbor, quickly became antiquated and fell into a steep decline. Additionally, by the late 1960s, the rail terminals and associated ferry service that were so vital to the city's economic health had closed and were later abandoned after the host railroads declared bankruptcy.[77] In response to adapt to this economic shift, Port Jersey was created on Upper New York Bay adjacent to Greenville Yard between 1972 and 1976 as the city's own modern intermodal freight transport facility and container shipping terminal.

By the 1970s the city experienced a period of urban decline spurred on by deindustrialization that saw many of its wealthy residents leave for the suburbs, due to rising crime, civil unrest, political corruption, and economic hardship. From 1950 to 1980, Jersey City lost 75,000 residents, and from 1975 to 1982, the city lost 5,000 jobs, or 9% of its workforce.[104]

In 1974, Hudson County Community College was established in Journal Square as one of two "contract" colleges in the United States and the first contract college in New Jersey to grant students occupational and career-oriented certificates and Associates in Applied Science degrees. Since then, the college has grown throughout the Journal Square and Bergen Square neighborhoods.[131]

On Flag Day 1976, Liberty State Park opened on New York Harbor to coincide with the nation's bicentennial. At 1,212 acres (490.5 ha) with a two-mile waterfront walkway, it is the largest park in Jersey City and the largest urban park in New Jersey. The park was built on the site of the former railyards of the Central Railroad of New Jersey and Lehigh Valley Railroad. The idea for the park dated back to the late 1950s and its creation was advocated for and spearheaded by several Jersey City residents: Audrey Zapp, Theodore Conrad, Morris Pesin and J. Owen Grundy. Jersey City donated 156 acres (63.1 ha) of land to the development of the park through their advocacy.[132][133][134] The Liberty Science Center opened in the park in 1993.

Late 20th and early 21st centuries

Beginning in the 1980s, the restoration of brownstones in neighborhoods such as Paulus Hook, Van Vorst Park, Hamilton Park, Harsimus Cove and Bergen Hill along with the development of the waterfront previously occupied by railyards, factories and warehouses helped to stir the beginnings of an economic renaissance for Jersey City.[135][136] The rapid construction of numerous high-rise buildings, such as the mixed-use community of Newport, increased the population and led to the development of the Exchange Place financial district, also known as "Wall Street West", one of the largest financial centers in the United States. Large financial institutions such as UBS, Goldman Sachs, Chase Bank, Citibank, and Merrill Lynch occupy prominent buildings on the Jersey City waterfront, some of which are among the tallest buildings in New Jersey. With 18,000,000 square feet (1,700,000 m2) of office space as of 2011, Jersey City has the nation's 12th-largest downtown and the state's largest office market.[137] Since 1988, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection has mandated by law that developers building along the waterfront preserve and develop the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway to provide the public with access and recreation by creating a linear park along the Hudson River.[138]

Simultaneous to this building boom, new transit projects were prioritized. By the late 1980s, trans-Hudson ferry service was restored along the waterfront by NY Waterway with ferry terminals now at Paulus Hook, Liberty Harbor and Port Liberté. From 1996 to 2011, NJ Transit constructed the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail as one of the largest public works projects in state history. The system was developed and extended throughout the city and its Downtown utilizing the former right-of-ways of the railroads that defined the city and county during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The system links Jersey City with its neighboring cities while connecting to several NJ Transit bus lines, PATH stations and ferry terminals.[139]

September 11, 2001

Jersey City was directly affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks at the World Trade Center where 38 city residents lost their lives. One of the 38 victims was Joseph Lovero, a Jersey City Fire Department dispatcher, who was killed by a piece of falling debris while responding.[140] The Jersey City Fire Department was the only New Jersey fire department to receive an official call for assistance from the New York City Fire Department that day.[141] Following the attacks, the Jersey City waterfront became the largest triage center in the area for survivors escaping Lower Manhattan by ferry during the "9/11 Boatlift". In the days and weeks after, Jersey City became a staging area for rescue and aid workers headed to "Ground Zero" for rescue and recovery efforts.[142] The collapse of the Twin Towers destroyed the World Trade Center PATH station and the firefighting efforts flooded the Downtown Hudson River tunnels and the Exchange Place PATH station severing the rail connection between Jersey City and Lower Manhattan until 2003.[143][144] Over the years several memorials have been erected along the waterfront including the Jersey City 9/11 Memorial and the official New Jersey state memorial Empty Sky.

On November 19, 2015, while campaigning for president in Birmingham, Alabama, Donald Trump falsely claimed a conspiracy theory that he witnessed people celebrating the attacks in Jersey City on television. Trump said:

Hey, I watched when the World Trade Center came tumbling down. And I watched in Jersey City, New Jersey, where thousands and thousands of people were cheering as that building was coming down. Thousands of people were cheering,

Trump continued to repeat the conspiracy theory to multiple news outlets for weeks, later adding that the people were Muslims, despite no confirmed reports, evidence or footage from that time being found to confirm his repeated falsehood.[145]

2010s–present

Jersey City was heavily impacted by Hurricane Sandy in October 2012 with extended power outages for multiple days, severe wind damage in several neighborhoods and extensive flooding throughout the city especially in Downtown, the Country Village neighborhood, the West Side and Liberty State Park. The flooding damaged the city's utility infrastructure and led to a days long shutdown of the PATH system, both of its Hudson River tunnels and the Holland Tunnel.[146][147][148][149][150]

In October 2013, City Ordinance 13.097 passed requiring employers with ten or more employees to offer up to five paid sick days a year. The bill impacts an estimated 30,000 workers at all businesses who employ workers who work at least 80 hours a calendar year in Jersey City.[151] The passage of the ordinance made Jersey City the first municipality in New Jersey and the sixth in the United States to guarantee paid sick leave.[152]

From 2018 to 2023, Jersey City built a new municipal complex called Jackson Square in the Jackson Hill section of the Bergen-Lafayette neighborhood. Planned since 2014, the city had previously rented office space throughout the city for its multiple agencies. The complex is made up of a City Hall Annex for several agencies, parking garage and public safety headquarters for the Jersey City Police and Fire Departments.[153][154]

Remove ads

Geography

Summarize

Perspective

Jersey City is the seat of Hudson County and the second-most-populous city in New Jersey.[31] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 21.13 square miles (54.74 km2), including 14.74 square miles (38.19 km2) of land and 6.39 square miles (16.55 km2) of water (30.24%).[10][11] As of the 1990 census, it had the smallest land area of the 100 most populous cities in the United States.[155]

The city is bordered to the east by the Hudson River, to the north by Secaucus, North Bergen, Union City and Hoboken, to the west, across the Hackensack River, by Kearny and Newark, and to the south by Bayonne.[156][157][158]

Jersey City includes most of Ellis Island (the parts awarded to New Jersey by the 1998 U.S. Supreme Court in the case of New Jersey v. New York). Liberty Island is surrounded by Jersey City waters in the Upper New York Bay. Given its proximity and various rapid transit connections to Manhattan, Jersey City (along with Hudson County as a whole) is sometimes referred to as New York City's sixth borough.[159][160][161]

Jersey City (and most of Hudson County) is located on the peninsula known as Bergen Neck, with a waterfront on the east at the Hudson River and New York Bay and on the west at the Hackensack River and Newark Bay. Its north–south axis corresponds with the ridge of Bergen Hill, the emergence of the Hudson Palisades.[162] The city is the site of some of the earliest European settlements in North America, which grew into each other rather than expanding from a central point.[163][164] This growth and the topography greatly influenced the development of the sections of the city and its various neighborhoods.[122][165][166]

Neighborhoods

The city is divided into six wards.[167]

Bergen-Lafayette

Bergen-Lafayette, formerly Bergen City, New Jersey, lies between Greenville to the south and McGinley Square to the north, while bordering Liberty State Park and Downtown to the east and the West Side neighborhood to the west. Communipaw Avenue, Bergen Avenue, Martin Luther King Drive, and Ocean Avenue are main thoroughfares. The former Jersey City Medical Center complex, a cluster of Art Deco buildings on a rise in the center of the city, has been converted into residential complexes called The Beacon.[168] Completed in 2016 at a cost of $38 million, (~$47.3 million in 2023) Berry Lane Park is located along Garfield Avenue in the northern section of Bergen-Lafayette; covering 17.5 acres (7.1 ha), it is the largest municipal park in Jersey City.[169] The Jersey City Municipal Complex opened in phases at Jackson Square in the Jackson Hill neighborhood from 2018 to 2023.[153][154]

Downtown Jersey City

Downtown Jersey City is the area from the Hudson River westward to the Newark Bay Extension of the New Jersey Turnpike (Interstate 78) and the New Jersey Palisades; it is also bounded by Hoboken to the north and Liberty State Park to the south.

Historic Downtown is an area of mostly low-rise buildings to the west of the waterfront that is highly desirable due to its proximity to local amenities and Manhattan. It includes the neighborhoods of Van Vorst Park and Hamilton Park, which are both square parks surrounded by brownstones. This historic downtown also includes Paulus Hook, the Village and Harsimus Cove neighborhoods. Newark Avenue & Grove Street, are the main thoroughfares in Downtown Jersey City, both have seen a lot of development and the surrounding neighborhoods have many stores and restaurants.[170] The Grove Street PATH station has been renovated and made fully ADA compliant.[171] and a number of new residential buildings are being built around the stop, including a 50-story building at 90 Columbus.[172] Historic Downtown is home to many cultural attractions including the Jersey City Museum, the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Powerhouse (planned to become a museum and artist housing) and the Harsimus Stem Embankment along Sixth Street, which a citizens' movement is working to turn into public parkland that would be modeled after the High Line in Manhattan.[173]

Newport and Exchange Place are redeveloped waterfront areas consisting mostly of residential towers, hotels and office buildings that are among the tallest buildings in the city. Newport is a planned mixed-use community, built on the old Erie Lackawanna Railway yards, made up of residential rental towers, condominiums, office buildings, a marina, schools, restaurants, hotels, Newport Centre Mall, a waterfront walkway, transportation facilities, and on-site parking for more than 15,000 vehicles. Newport had a hand in the renaissance of Jersey City although, before ground was broken, much of the downtown area had already begun a steady climb (much like Hoboken).

The Heights

The Heights or Jersey City Heights is a district in the north end of Jersey City atop the New Jersey Palisades overlooking Hoboken to the east and Croxton in the Meadowlands to the west. Previously the city of Hudson City, The Heights was incorporated into Jersey City in 1869.[93] The southern border of The Heights is generally considered to be north of Bergen Arches and the Covered Roadway, while Paterson Plank Road in Washington Park is its main northern boundary. Transfer Station is just over the city line. Its postal area ZIP Code is 07307. The Heights mostly contains two- and three-family houses and low rise apartment buildings, and is similar to North Hudson architectural style and neighborhood character.[174]

Journal Square

Journal Square is a mixed-use central business district. The square was created in 1923, creating a broad intersection with Hudson Boulevard which itself had been widened in 1908.[175] Other major squares in the neighborhood are Bergen Square, India Square and Five Corners. McGinley Square is located in close proximity to Journal Square, and is considered an extension of it.[176] Hudson County Community College is located throughout the neighborhood. Journal Square is currently undergoing a massive wave of economic growth and development not seen since the neighborhood was first established with more than 4,400 residential units under construction.[177]

Greenville

Greenville is on the south end of Jersey City. In the 2010s, the neighborhood underwent a revitalization.[178] Considered an affordable neighborhood in the New York City area, a number of Ultra-Orthodox Jews and young families purchased homes and built a substantial community there, attracted by housing that costs less than half of comparable homes in New York City.[179] In a December 2019 shooting incident, three bystanders were killed in a kosher market in Greenville. The two assailants, who had earlier killed a police detective, were also shot and killed.[180]

West Side

The West Side borders Greenville to the south and the Hackensack River to the west; it is also bounded to the east and north by Bergen-Lafayette and the broader Journal Square area, including McGinley Square. It consists of various diverse areas on both sides of West Side Avenue, one of Jersey City's leading shopping streets.[181] The West Side is the home of New Jersey City University and Saint Peter's University.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally cool to cold winters with moderate snowfall. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Jersey City has a humid subtropical climate (closely bordering on a humid continental climate), similar to its parallel cities like Newark and New York City.[182]

Remove ads

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

As of the 2020 census, Jersey City had a population of 292,449, and a population density of 19,835.1 inhabitants per square mile (7,658.4/km2)[20] an increase of 44,852 residents (18.1%) from its 2010 census population of 247,597.[33] Since it was believed the earlier population was under-counted, the 2010 census was anticipated with the possibility that Jersey City might become the state's most populated city, surpassing Newark.[193] The city hired an outside firm to contest the results, citing the fact that development in the city between 2000 and 2010 substantially increased the number of housing units and that new populations may have been under-counted by as many as 30,000 residents based on the city's calculations.[194][195] Preliminary findings indicated that 19,000 housing units went uncounted.[196]

Per the American Community Survey's 2014–2018 estimates, Jersey City's age distribution was 7.7% of the population under 5, 13.2% between 6–18, 69% – from 19 to 64, and 10.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age 34.2 years.[197] Females made up 50.8% of the population and there were 100.1 males per 100 females. 86.5% of the population graduated high school, while 44.9% of the population had a bachelor's degree or higher. 7.1% of residents under 65 were disabled, while 15.9% of residents live without health insurance.[198]

There were 110,801 housing units and 102,353 households in 2018.[199] The average household size was 2.57. The average per capita income was $36,453, and the median household income was $62,739. 18.7% of residents lived below the poverty line. 67.9% of residents 16+ were within the civilian labor force. The mean travel time to work for residents was 36.8 minutes. 28.6% of housing units are owner-occupied, with the median value of the homes being $344,200. The median gross rent in the city was $1,271.[198]

From 2005 to 2023, Jersey City led New Jersey and the Northeastern United States in housing construction with a 43% increase producing twice as much housing as the rest of the state and 16.7% more than the United States average. Additionally, the city's population increased by 18% with a 20% increase in housing units resulting in housing development surpassing population growth. During this time, the median household income in Jersey City grew by 133%, the fourth-highest increase in the United States with the median home price increasing by 86%. Over this time, Jersey City has matched or surpassed the number of housing units created in Manhattan in a given year. In 2024, Jersey City ranked third in the New York metropolitan area for new apartment construction behind only Brooklyn and Manhattan and ahead of Queens with Jersey City building twice as many units.[200][201][202] In January 2025, the addition of new rental units to the city's market led to a median rent of $3,050 for one-bedroom units, a decrease of 2.9% year-over-year and a median rent of $3,340 for two-bedroom units, a decrease of 12.1% year-over-year.[203]

Race and ethnicity

Jersey City has been called "one of the most diverse cities in the world" and for several years has been ranked as the most ethnically diverse city in the United States.[207] The city is a major port of entry for immigration to the United States and a major employment center at the approximate core of the New York City metropolitan area; and given its proximity to Manhattan, Jersey City has evolved a globally cosmopolitan ambiance of its own, demonstrating a robust and growing demographic and cultural diversity concerning metrics including "nationality, religion, race, and domiciliary partnership."[208][37][209]

Jersey City has undertaken several measures to engage its different immigrant communities. In 2017, Jersey City designated itself a "sanctuary city".[210] In 2018, Jersey City created the Division of Immigrant Affairs within the Department of Health and Human Services. The office works to address the concerns of immigrant communities and build partnerships with nonprofit organizations that serve them specifically in health and human services, immigration legal services, education and English language acquisition, job training, enrollment in public benefits and civic engagement. In 2020, Jersey City became the first municipality in the United States accredited for offering free legal services to immigrants as part of the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) Recognition and Accreditation Program. Additionally, The New American Economy (NAE) Research Award named Jersey City to receive NAE research to further address socioeconomic disparities within immigrant populations.[211][212]

The U.S. Census accounts for race by two methodologies. "Race alone" and "Race alone less Hispanics" where Hispanics are delineated separately as if a separate race.

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the racial makeup (including Hispanics in the racial counts) was 27.32% (79,905) White alone, 19.87% (58,103) Black alone, 0.66% (1,916) Native American alone, 28.01% (81,903) Asian alone, 0.06% (178) Pacific Islander alone, 14.35% (41,970) Other Race alone, and 9.74% (28,474) Multiracial or Mixed Race.[217]

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the racial and ethnic makeup (where Hispanics are excluded from the racial counts and placed in their own category) was 23.81% (69,624) White alone (non-Hispanic), 18.53% (54,199) Black alone (non-Hispanic), 0.22% (638) Native American alone (non-Hispanic), 27.84% (81,425) Asian alone (non-Hispanic), 0.03% (101) Pacific Islander alone (non-Hispanic), 1.44% (4,204) Other Race alone (non-Hispanic), 3.24% (9,481) Multiracial or Mixed Race (non-Hispanic), and 24.89% (72,777) Hispanic or Latino.[216]

There were an estimated 55,493 non-Hispanic whites in Jersey City, according to the 2013–2017 American Community Survey,[218] representing a 4.2% increase from 53,236 non-Hispanic whites enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219]

An estimated 63,788 African Americans resided in Jersey City, or 24.0% of the city's population in 2017,[218] representing a slight decrease from 64,002 African Americans enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219] This is in contrast with Hudson County overall, where there were an estimated 84,114 African Americans, according to the 2013–2017 American Community Survey,[220] representing a 2.3% increase from 83,925 African Americans enumerated in the county in the 2010 United States census.[221] However, modest growth in the African immigrant population, most notably the growing Nigerian American and Kenyan American populations[222][223] in Jersey City, is partially offsetting the decline in the city's American-born black population, which as a whole has been experiencing an exodus from northern New Jersey to the Southern United States.[224]

Approximately 76,637 Latino and Hispanic Americans lived in Jersey City, composing 28.8% of the population in 2017,[218] representing a 12.3% increase from 68,256 Latino or Hispanic Americans enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219][208] Stateside Puerto Ricans, making up a third of the city's Latin American or Hispanic population, constituted the largest Hispanic group in Jersey City.[218] Since 1961, Jersey City has hosted its annual Puerto Rican Day Parade and Festival which has grown to be the largest in the state.[225] While Cuban Americans are not as highly concentrated in Jersey City as they are in northern Hudson County, Jersey City has hosted the annual Cuban Parade and Festival of New Jersey at Exchange Place on its downtown waterfront since it was established in 2001.[226]

An estimated 67,526 Asian Americans live in Jersey City, constituting 25.4% of the city's population,[218] representing a 15.2% increase from 58,595 Asian Americans enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219]

India Square, also known as "Little India", "Little Bombay",[228] or "Little Gujarat",[229] home to the highest concentration of Asian Indians in the Western Hemisphere,[227] is a rapidly growing Indian American ethnic enclave in Jersey City. Indian Americans constituted 10.9% of the overall population of Jersey City in 2010,[33] the highest proportion of any major U.S. city. India Square has been home to the largest outdoor Navratri festivities in New Jersey as well as several Hindu temples;[230] while an annual, color-filled spring Holi festival has taken place in Jersey City since 1992, centered upon India Square and attracting significant participation and international media attention.[231][232] In 2017 there were an estimated 31,578 Indian Americans in Jersey City,[218] representing a 16.5% increase from 27,111 Indian Americans enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219]

Filipino Americans, numbering 16,610 residents, made up 6.2% of Jersey City's population in 2017.[218][233] The Five Corners district serves as a prominent Little Manila of Jersey City, being home to a thriving Filipino community that forms the second-largest Asian-American subgroup in the city.[33] A variety of Filipino restaurants, shippers and freighters, doctors' offices, bakeries, stores, and even an office of The Filipino Channel have made Newark Avenue their home in recent decades. The largest Filipino-owned grocery store on the East Coast, Phil-Am Food, has been established on the avenue since 1973.[234] An array of Filipino-owned businesses can also be found in the West Side section of the city, where many residents are of Filipino descent. In 2006, Red Ribbon Bakeshop, one of the Philippines' most famous food chains, opened its first branch on the East Coast: a new pastry outlet in Jersey City.[235] Manila Avenue in Downtown Jersey City was named for the Philippine capital city because of the many Filipinos who built their homes on the street during the 1970s. A memorial dedicated to the Filipino-American veterans of the Vietnam War was built in a small square on Manila Avenue. A park and statue dedicated to Jose P. Rizal, a national hero of the Philippines, are also located in Downtown Jersey City.[236] Furthermore, Jersey City hosts the annual Philippine–American Friendship Day Parade along West Side Avenue ending at Lincoln Park with a day long festival, an event that occurs yearly on the last Sunday in June.[237] The City Hall of Jersey City raises the Philippine flag in correlation with this event and as a tribute to the contributions of the local Filipino community. The city's annual Santacruzan procession has taken place since 1977 along Manila Avenue.[238]

Behind English and Spanish, Tagalog is the third-most-common language spoken in Jersey City.[239]

Jersey City was home to an estimated 9,379 Chinese Americans in 2017,[218] representing a notably rapid growth of 66.2% from the 5,643 Chinese Americans enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219] Chinese nationals have also been obtaining EB-5 immigrant visas by investing US$500,000 apiece in new Downtown Jersey City residential skyscrapers.[240]

New Jersey's largest Vietnamese American population resides in Jersey City. There were an estimated 1,813 Vietnamese Americans in Jersey City, according to the 2013–2017 American Community Survey,[218] representing a 12.8% increase from 1,607 Vietnamese Americans enumerated in the 2010 United States census.[219]

Arab Americans numbered an estimated 18,628 individuals in Hudson County per the 2013–2017 American Community Survey, representing 2.8% of the county's total population.[241] Arab Americans are the second- highest percentage in New Jersey after Passaic County.[242] Arab Americans are most concentrated in Jersey City, led by Egyptian Americans, including the largest population of Coptic Christians in the United States.[208]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

In 2010, there were 2,726 same-sex couples in Hudson County, with Jersey City being the hub,[243] prior to the commencement of same-sex marriages in New Jersey on October 21, 2013.[244] Following the ruling, Jersey City was one of the first municipalities in New Jersey to issue marriage licenses and officiate ceremonies for same-sex couples. Jersey City is considered one of the most LGBT-friendly communities in New Jersey and has achieved a perfect score from the Municipal Equality Index (MEI) for LGBTQ+ equality in municipal law, policies, and services for 12 consecutive years.[245][246]

Founded in 1993, the Hudson Pride Connections Center is located in Journal Square and is largest LGBTQ+ social services center in New Jersey that advocates for the physical, mental, social and political well-being of the diverse LGBTQ+ community and its supporters.[247]

Every August since 2000 Jersey City hosts the Jersey City LBGTQ+ Pride Festival (JC Pride) which has grown to become one of the largest pride festivals in New Jersey attracting over 25,000 attendees. The celebrations begin on the first of the month with a Progress Pride Flag raising ceremony at City Hall.[248][249]

Religion

Nearly 59.6% of Jersey City's inhabitants are religious adherents, of which 46.2% are Catholic Christians and 7.3% are Protestant Christians.[250] Muslims constituted 3.4% of religious adherents in Jersey City. Dharmic religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Sikhism make up 1.5% of the city's religious demographic, with Judaism at 0.6%.[250] Jersey City has a growing Orthodox Jewish population, centered in the Greenville neighborhood.[251]

Remove ads

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

Jersey City is a regional employment center and one of the largest in the state with over 100,000 private and public sector jobs, which creates a daytime swell in population. Many jobs are in the financial and service sectors, as well as in shipping, logistics, and retail.[252] From 2020 to 2021, Jersey City's employment rate increased by 8.12% from 140,000 to 151,000 employees. Tech and IT jobs made up 15.5% of all jobs created during that span.[253]

Jersey City's tax base grew by US$136 million in 2017, giving Jersey City the largest municipal tax base in the State of New Jersey.[254] As part of a 2017 revaluation, the city's property tax base is expected to increase from $6.2 billion to $26 billion.[255]

Wall Street West

Jersey City's Hudson River waterfront, from Exchange Place to Newport, is known as Wall Street West and has over 13,000,000 square feet (1,200,000 m2) of Class A office space[252] and over 18,000,000 square feet (1,700,000 m2) of total office space for the nation's 12th-largest downtown and the state's largest office market.[137] One-third of the private sector jobs in the city are in the financial services sector: more than 60% are in the securities industry, 20% are in banking and 8% in insurance.[256]

Jersey City is the headquarters of the National Stock Exchange. Jersey City is also home to the headquarters of Verisk Analytics and Lord Abbett,[257] a privately held money management firm.[258] Companies such as Computershare, ADP, IPC Systems, and Fidelity Investments also conduct operations in the city.[259] Fintech firms such as Revenued also have a large presence to service the financial sector in Jersey City.[260] In 2014, Forbes magazine moved its headquarters to the district, having been awarded a $27 million tax grant in exchange for bringing 350 jobs to the city over ten years.[261] Also in 2014, RBC Bank announced it was moving 900 jobs to 207,000 sq ft (19,200 m2) of office space at 30 Hudson Street at Exchange Place.[262] In 2015, JPMorgan Chase expanded their presence in Jersey City by relocating 2,150 jobs from Manhattan to a company owned office building in Newport.[263] In 2020, American International Group (AIG) announced it was leasing 230,000 sq ft (21,000 m2) of office space at 30 Hudson St. starting in 2021.[264] The Bank of Montreal renewed its lease of 10,365 sq ft (962.9 m2) office space in 2024 at Harborside.[265] In 2024, Bank of America announced that they leased approximately 550,000 sq ft (51,000 m2) of office space over 21 floors at Newport Tower in the Newport neighborhood. It represents the largest New Jersey office space lease in the last decade.[266]

Life science and technology industry

The life science and technology industry is a rapidly growing and expanding sector for Jersey City. In 2024, Jersey City was ranked as the 5th top tech city in the United States and now houses 394 different Tech and IT firms with 15.5% of all jobs in Jersey City being created in that sector from 2020 to 2021.[253]

In 2020, Merck & Co spin-off Organon International leased 110,000 sq ft (10,000 m2) of office space and locate its headquarters at the Goldman Sachs Tower via WeWork.[267]

In 2021, the Liberty Science Center broke ground on SciTech Scity, a 30 acres (0.12 km2) campus across the street from the science center that will serve as a hub for life sciences, health care and technology. The $450 million campus will include Edge Works, an eight-story facility that will feature laboratories, research and development spaces, office suites, co-working spaces for startups, a tech exhibition hall and a state-of-the-art conference center. Sheba Medical Center is an anchor tenant and will develop a "hospital of the future" simulation space that will be known as "Liberty Science ARC HealthSpace 2030". Additionally, the campus will include Liberty Science Center High School, a new STEM public high school that will be administered by the Hudson County Schools of Technology and Scholars Village, a 500-unit residential project that will marketed toward families and individuals in tech related industries.[268][269]

Another life science and innovation hub called "The Cove" was announced in 2022. The 13 acres (0.053 km2) campus site is near SciTech Scity and will be a mixed-use development with 1,400,000 sq ft (130,000 m2) of life science office and research space, 1,600,000 sq ft (150,000 m2) of residential space and feature a 3.5 acres (0.014 km2) public waterfront park.[270]

In 2023, the biotechnology firm EpiBone, a company that grows bone and cartilage for skeletal reconstruction, announced it would move from Brooklyn to Jersey City and lease 28,089 sq ft (2,609.6 m2) of lab space at 95 Greene Street, a purpose built life science facility at Exchange Place.[271] The following year in 2024, RegenLab USA, which manufactures devices for the production of regenerative cell therapy, announced that they would also move from Brooklyn to Jersey City and lease 15,792 sq ft (1,467.1 m2) of lab space in the same facility.[272]

In 2024, biopharmaceutical company Eikon Therapeutics moved into 36,000 sq ft (3,300 m2) of office space at Harborside.[265]

In 2025, AI and IT company Hexaware Technologies leased the entire the 24th floor of Harborside 5 for their global headquarters.[273]

Sports betting

Jersey City has quickly grown to be a leader in the sports betting industry and the sports betting epicenter of the United States. BetMGM and Caesars Sports Book have established their headquarters at Exchange Place along the Hudson River Waterfront and several other sports book such as FanDuel, Draft Kings and Fanatics have offices in Jersey City. FanDuel expanded their operations with a new 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) office at Newport in 2025.[274] With New Jersey having a long history of legalized gambling and also being a hub for tech employees, Jersey City has become an extension of the gaming industry in Atlantic City.[275]

Retail

Jersey City has several shopping districts, some of which are traditional main streets for their respective neighborhoods, such as Central, Danforth, Newark and West Side Avenues. Lower Newark Avenue in Downtown Jersey City was converted to a permanent three-block long pedestrian plaza in 2022 becoming a hub for the city's dining, nightlife and cultural arts scene.[276] Journal Square is a major historic commercial and central business district that includes neighborhoods in the broader area such as Bergen Square, McGinley Square, India Square, the Five Corners and portions of the Marion Section. Jersey City has two malls, Newport Centre Mall, a regional indoor shopping mall in Downtown Jersey City, and Hudson Mall, a "non traditional" indoor shopping mall on the city's West Side.[181]

Portions of the city are part of an Urban Enterprise Zone (UEZ). Jersey City was selected in 1983 to be part of the initial group of 10 zones chosen to participate in the program.[277] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment and investment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6.625% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[278] Established in November 1992, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in November 2023.[279] Jersey City is the state's largest and most productive Urban Enterprise Zone encompassing one-third of the city.[280][281]

E-commerce and distribution

In 2013, Imperial Dade opened its 535,000 square feet (49,700 m2) distribution center and headquarters on U.S. Route 1/9 Truck in the Marion neighborhood on the city's West Side.[282]

East Coast Warehouse and Distribution expanded its warehouse operations by 200,000 square feet (19,000 m2) in 2017.[283]

Goya Foods, which had been headquartered in adjacent Secaucus, opened a new headquarters including a 600,000-square-foot (56,000 m2) warehouse and distribution center in Jersey City in April 2015.[284]

In 2019, Nuts.com moved its headquarters to 25,000 sq ft (2,300 m2) of office space at Exchange Place in Jersey City.[285]

In 2024, CVS Health leased 427,000 square feet (39,700 m2) of space at the newly constructed 86 acres (0.35 km2) HRP Hudson Logistics Park in the Croxton section of Jersey City.[286]

Port Jersey

Port Jersey is an intermodal freight transport facility that includes a container terminal located on the Upper New York Bay in the Port of New York and New Jersey. The municipal border of the Hudson County cities of Jersey City and Bayonne runs along the long pier extending into the bay.

The north end of the facility houses the Greenville Yard, a rail yard located on a manmade peninsula that was built in the early 1900s by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[287][288] New York New Jersey Rail is a switching and terminal railroad headquartered in Greenville Yard that operates the only car float in New York Harbor between Jersey City and Brooklyn. Operations were expanded in 2017 with a new barge, NYNJR100, that features four tracks that can carry up to 18 rail cars of 60-foot (18 m) length, with up to 2,298 long tons (2,335 tonne) of cargo.[289] A second barge of the same capacity, NYNJR200, was delivered in 2018 with an older 14-car barge, the 278, still in service.[290] In 2019, the $600 million expansion was completed with the construction of an Express Rail facility that features 9,600 ft (2,900 m) of track over eight tracks serviced by two rail mounted gantry cranes with a yearly capacity of 250,000 container lifts.

The central area of the facility contains Port Liberty Bayonne, a major post-panamax shipping facility operated by CMA CGM that underwent a major expansion in June 2014.[291][292] The largest ship ever to call at the Port of New York-New Jersey, the MOL Benefactor, docked at Port Jersey in July 2016 after sailing from China through the newly widened Panama Canal.[293] In 2024, Port Jersey received four new super post panamax cranes capable of serving 24,000 twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) vessels raising the number of cranes at the port from eight to twelve. Additionally, work is ongoing to create a third berth for vessels with a depth of 55 feet (17 m).[294]

Other

In 2014, the apparel and foot ware company, VF Corporation, moved 145 workers from Manhattan to 42,000 sq ft (3,900 m2) of office space in Newport.[295]

In 2022, the sports memorabilia company, Collectors Holdings, owned by New York Mets owner Steve Cohen, leased 130,000 sq ft (12,000 m2) of space for its authentication and grading services at Harborside 3 along the Hudson River Waterfront.[296]

In 2025, electronics company Casio America Inc. leased 13,647 sq ft (1,267.8 m2) at Harborside 5 for their new sales and marketing headquarters.[297]

In 2014, Paul Fireman proposed a 95-story tower for Jersey City that would have included a casino next to Liberty National Golf Club. The project, which was endorsed by Mayor Steven Fulop, would cost an estimated $4.6 billion (~$5.83 billion in 2023).[298] In February 2014, New Jersey State Senate President Stephen Sweeney argued that Jersey City, among other distressed cities, could benefit from a casino—were construction of one outside of Atlantic City eventually permitted by New Jersey.[299] In 2016, the New Jersey Casino Expansion Amendment (2016) ballot question was put before New Jersey voters asking them if they would allow the expansion of casino gambling outside Atlantic City via a constitutional amendment. Voters rejected the ballot question by a margin of 77% to 23% effectively ending the casino proposal.

Remove ads

Notable landmarks

- Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island (Liberty Island and part of Ellis Island are located in New York, but both islands are closer to the New Jersey shoreline.)[300]

- The Liberty Science Center, is a 300,000-square-foot (28,000 m2) science museum and learning center located in Liberty State Park.[301]

- The Peter Stuyvesant Monument by J. Massey Rhind is a memorial to Peter Stuyvesant and the establishment of settlement of Bergen, New Netherlands in 1660. Erected in 1910 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the establishment of Bergen.

- The Katyń Memorial by Polish-American artist Andrzej Pitynski on Exchange Place is the first memorial of its kind to be raised on American soil to honor the dead of the Katyń Forest Massacre.[302]

- The Lincoln the Mystic is a memorial honoring Abraham Lincoln by James Earle Fraser at the entrance to Lincoln Park.[303]

- The Colgate Clock, promoted by Colgate-Palmolive as the largest in the world, sits in Jersey City and faces Lower New York Bay and Lower Manhattan (it is clearly visible from Battery Park in lower Manhattan). The clock, which is 50 feet (15 m) in diameter with a minute hand weighing 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg), was erected in 1924 to replace a smaller one that was relocated to a plant in Jeffersonville, Indiana.[304]

- The Landmark Loew's Jersey Theatre, one of the five Loew's Wonder Theatres constructed in the 1920s and the only one located outside of New York City, is located in Journal Square. Currently presenting classic films, live performances, and events while the theatre undergoes restoration by volunteers.[305][306]

- The Van Wagenen House, also known as the "Apple Tree House". Built in 1740, it is one of the oldest structures in Jersey City and is the purported site of a meeting between George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette in 1779 during the Revolutionary War. It is now home to the Museum of Jersey City History.[307]

- The White Eagle Hall is a renovated and re-opened historic theater.[308] Constructed in 1910, it had served as the practice gym for the Saint Anthony High School Friars basketball program.[309]

- The Jersey City 9/11 Memorial erected to memorialize the 38 Jersey City residents that were killed during the September 11 attacks at the World Trade Center. The site of the memorial was a triage set up during the '9/11 boatlift' operation and afterwards became a staging area for rescue operations.[310]

- The Empty Sky memorial, designed by Jessica Jamroz and Frederic Schwartz, is located in Liberty State Park and honors the 746 New Jerseyans that were killed during the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and September 11 attacks.[311]

- The Statue of Mary McLeod Bethune designed by Alvin Petit who said "As a broader significance, this also plays a role in linking our City with a national movement to erect monuments that symbolize diversity and inclusiveness. This will be the first statue in Jersey City to honor the legacy of an African American woman."[312]

Remove ads

Art and culture

Summarize

Perspective

Based upon a 2011 survey of census data on the number of artists as a percentages of the population, The Atlantic magazine called Jersey City the 10th-most-artistic city in the United States.[313][314] In 2023, Americans for the Arts released the Arts & Economic Prosperity 6 (AEP6) study on the nation's non-profit arts and culture sector. The study found that in 2022 Jersey City's arts and culture sector generated $46 million in economic activity while supporting 532 jobs, providing $28.2 million in personal income to residents and generating $7.1 million in local, state and federal tax revenue.[315]

Museums, libraries and galleries

The Jersey City Free Public Library is the largest municipal library system in New Jersey. It has a Main Library, bookmobile and ten branches with the newest branch, the Communipaw Branch, opening in 2024 in the Communipaw-Lafayette neighborhood as a public innovation hub for Jersey City and a hub for STEAM learning, equipped with a makerspace that includes a range of tools from 3D printers to a recording studio.[316][317]

The Main Library Branch features the New Jersey Room, a wing dedicated to historical documents about New Jersey, with a focus on Hudson County and Jersey City. Created in 1964, the room merged the collections of William H. Richardson and the Hudson County Historical Society with material the library already possessed.[318] The New Jersey Room holds over 20,000 volumes, in addition to historical maps and periodicals.[319][320]

The Afro-American Historical and Cultural Society Museum is located on the upper floor of the Greenville Branch of the Jersey City Public Library and features the heritage of Jersey City's African American community which has been preserved in a special collection. Additionally, a permanent collection of material culture of New Jersey's African Americans as well as African artifacts is also on display.[321]

The Museum of Jersey City History is located in the historic Van Wagenen House on Bergen Square and features rotating and permanent exhibitions on the history of Jersey City.[322]

Liberty State Park is home to the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal, the Interpretive Center, and Liberty Science Center, an interactive science and learning center. The center, which first opened in 1993 as New Jersey's first major state science museum, has science exhibits, the world's largest IMAX Dome theater, numerous educational resources, and the original Hoberman sphere.[323] In 2017, the center debuted the Jennifer Chalsty Planetarium, the largest in the Western Hemisphere and the fourth largest in the world.[324] From the park, ferries travel to both Ellis Island and the Immigration Museum and Liberty Island, site of the Statue of Liberty.[325]