Racism in Australia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Racism in Australia comprises negative attitudes and views on race or ethnicity which are held by various people and groups in Australia, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and actions (including violence) at various times in the history of Australia against racial or ethnic groups.[1]

Racism against various ethnic or minority groups has existed in Australia since British colonisation. Throughout Australian history, the Indigenous peoples of Australia have faced severe restrictions on their political, social, and economic freedoms, and suffered genocide,[2] forced removals,[3] and massacres,[4] and continue to face discrimination.[5][6][7] African, Asian, Pacific Islander and Middle Eastern Australians have also been the victims of discrimination.[8][9][10][11] In addition, Jews, Italians and the Irish were often subjected to xenophobic exclusion and other forms of religious and ethnic discrimination.[12][13][14]

Racism has manifested itself in a variety of ways, including segregation,[15] racist immigration[16] and naturalisation[17] laws, and internment camps.[18][19][20]

Background

Summarize

Perspective

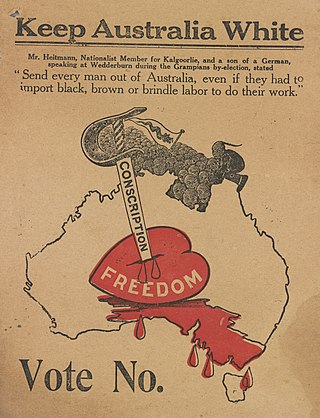

White Australia policy

Following the establishment of autonomous parliaments, a rise in nationalism and improvements in transportation, the Australian colonies voted to unite in a Federation, which came into being in 1901. The Australian Constitution and early parliaments established one of the most progressive governmental systems on the earth at that time, with male and female suffrage and series of checks and balances built into the governmental framework. National security fears had been one of the chief motivators for the union and legislation was quickly enacted to restrict non-European immigration to Australia – the foundation of the White Australia policy – and voting rights for Aboriginal people were denied across most states.

Australia's official World War One historian Charles Bean defined the early intentions of the policy as "a vehement effort to maintain a high Western standard of economy, society and culture (necessitating at that stage, however it might be camouflaged, the rigid exclusion of Oriental people)."[21]

The new Parliament quickly moved to restrict immigration to maintain Australia's "British character",[citation needed] and the Pacific Island Labourers Bill and the Immigration Restriction Bill were passed shortly before parliament rose for its first Christmas recess. Nevertheless, the Colonial Secretary in Britain made it clear that a race-based immigration policy would run "contrary to the general conceptions of equality which have ever been the guiding principle of British rule throughout the Empire", so the Barton government conceived of the "language dictation test", which would allow the government, at the discretion of the minister, to block unwanted migrants by forcing them to sit a test in "any European language". Race had already been established as a premise for exclusion among the colonial parliaments, so the main question for debate was who exactly the new Commonwealth ought to exclude, with the Labor Party rejecting Britain's calls to placate the populations of its non-white colonies and allow "aboriginal natives of Asia, Africa, or the islands thereof". There was opposition from Queensland and its sugar industry to the proposals of the Pacific Islanders Bill to exclude "Kanaka" labourers, however Barton argued that the practice was "veiled slavery" that could lead to a "negro problem" similar to that in the United States and the Bill was passed.[22]

Demise of the White Australia policy

The restrictive measures established by the first parliament gave way to multi-ethnic immigration policies only after the Second World War, with the "dictation test" itself being finally abolished in 1958 by the Menzies Government.[23]

The Menzies Government instigated migrants over all others since the time of Australian Federation in 1901 and abolished restrictions on voting rights for Aboriginal people, which had persisted in some jurisdictions. In 1950 External Affairs Minister Percy Spender instigated the Colombo Plan, under which students from Asian countries were admitted to study at Australian universities, then in 1957 non-Europeans with 15 years' residence in Australia were allowed to become citizens. In a watershed legal reform, a 1958 revision of the Migration Act introduced a simpler system for entry and abolished the "dictation test" which had permitted the exclusion of migrants on the basis of their ability to take down a dictation offered in any European language. Immigration Minister, Sir Alexander Downer, announced that 'distinguished and highly qualified Asians' might immigrate. Restrictions continued to be relaxed through the 1960s in the lead up to the Holt government's watershed Migration Act, 1966.[23]

Holt's government introduced the Migration Act 1966, which effectively dismantled the White Australia policy and increased access to non-European migrants, including refugees fleeing the Vietnam War. Holt also called the 1967 Referendum which removed the discriminatory clause in the Australian Constitution which excluded Aboriginal Australians from being counted in the census;– the referendum was one of the few to be overwhelmingly endorsed by the Australian electorate (over 90% voted 'yes').[24]

The legal end of the White Australia Policy is usually placed in 1973, when the Whitlam Labor government implemented a series of amendments preventing the enforcement of racial aspects of the immigration law. These amendments:[25]

- Legislated that all migrants, regardless of origin, be eligible to obtain citizenship after three years of permanent residence.

- Ratified all international agreements relating to immigration and race.

- Issued policy to totally disregard race as a factor in selecting migrants.

The 1975 Racial Discrimination Act made the use of racial criteria for any official purpose illegal (with the exception of census forms).

2000s

A 2003 Paper by health economist Gavin Mooney said that "Government institutions in Australia are racist". The paper evidenced this opinion by stating that the Aboriginal Medical Service was underfunded and under supported by government.[26][27][28]

In 2007, What's the Score? A survey of cultural diversity and racism in Australian sport conducted by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) said that "racial abuse and vilification is commonplace in Australian sport... despite concerted efforts to stamp it out". The report said that Aboriginal and other ethnic groups are under-represented in Australian sport, and suggests they are turned off organised sport because they fear racial vilification.[29][30] Despite the finding, indigenous participation in Australian sport is widespread. In 2009, about 90,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were participating in Australian Rules Football alone and the Australian Football League (AFL) encouraged their participation through the Kickstart Indigenous programs "as the vehicle to improve the quality of life in Indigenous communities, not only in sport, but in the areas of employment, education and health outcomes".[31] Similarly, Australia's second most popular football code encourages participation through events like the NSW Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout and the Indigenous All Stars Team.[32]

2005 UN report

The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in its report,[33] released in 2005 was complimentary on improvements in race-related issues since its previous report five years prior, namely:[citation needed]

- the criminalising of acts and incitement of racial hatred in most Australian states and territories

- progress in the economic, social and cultural rights by Indigenous peoples

- programmes and practices among the police and the judiciary, aimed at reducing the number of Indigenous juveniles entering the criminal justice system

- the adoption of a Charter of Public Service in a Culturally Diverse Society to ensure that government services are provided in a way that is sensitive to the language and cultural needs of all Australians

- and the numerous human rights education programmes developed by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC)

The committee expressed concern about the abolishment of ATSIC; proposed reforms to HREOC that may limit its independence; the practical barriers Indigenous peoples face in succeeding in claims for native title; a lack of legislation criminalising serious acts or incitement of racial hatred in the Commonwealth, the State of Tasmania and the Northern Territory; and the inequities between Indigenous peoples and others in the areas of employment, housing, longevity, education and income.[34][citation needed]

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

It is estimated that the population of Aboriginal peoples prior to the European colonisation of Australia (starting in 1788) was about 314,000.[35] It has also been estimated by ecologists that the land could have supported a population of a million people. By 1901, they had been reduced by two-thirds to 93,000. In 2011, First Nations Australians (including both Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander people) comprised about 3% of the total population, at 661,000. When Captain Cook landed in Botany Bay in 1770, he was under orders not to plant the British flag and to defer to any native population, which was largely ignored.[36]

Land rights, stolen generations, and terra nullius

Torres Strait Islander people are indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands, which are in the Torres Strait between the northernmost tip of Queensland and Papua New Guinea. Institutional racism had its early roots here due to interactions between these islanders, who had Melanesian origins and depended on the sea for sustenance and whose land rights were abrogated, and later the Australian Aboriginal peoples, whose children were removed from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments.[37][38] The removals occurred in the period between approximately 1909 and 1969, resulting in what later became known as the Stolen Generations. An example of the abandonment of mixed-race ("half-caste") children in the 1920s is given in a report by Walter Baldwin Spencer that many mixed-descent children born during construction of The Ghan railway were abandoned at early ages with no one to provide for them. This incident and others spurred the need for state action to provide for and protect such children. Both were official policy and were coded into law by various acts. They have both been rescinded and restitution for past wrongs addressed at the highest levels of government.[39]

The treatment of the First Nations Australians by the colonisers has been termed cultural genocide.[40] The earliest introduction of child removal to legislation is recorded in the Victorian Aboriginal Protection Act 1869.[41] The Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines had been advocating such powers since 1860, and the passage of the Act gave the colony of Victoria a wide suite of powers over Aboriginal and "half-caste" persons, including the forcible removal of children,[42] especially "at risk" girls.[43] By 1950, similar policies and legislation had been adopted by other states and territories, such as the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Qld),[44] the Aborigines Ordinance 1918 (NT),[45] the Aborigines Act 1934 (SA)[46] and the 1936 Native Administration Act (WA).

The child-removal legislation resulted in widespread removal of children from their parents and exercise of sundry guardianship powers by Protectors of Aborigines up to the age of 16 or 21. Policemen or other agents of the state were given the power to locate and transfer babies and children of mixed descent from their mothers or families or communities into institutions.[47] In these Australian states and territories, half-caste institutions (both government Aboriginal reserves and church-run mission stations) were established in the early decades of the 20th century for the reception of these separated children. Examples of such institutions include Moore River Native Settlement in Western Australia, Doomadgee Aboriginal Mission in Queensland, Ebenezer Mission in Victoria and Wellington Valley Mission in New South Wales.

In 1911, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in South Australia, William Garnet South, reportedly "lobbied for the power to remove Aboriginal children without a court hearing because the courts sometimes refused to accept that the children were neglected or destitute". South argued that "all children of mixed descent should be treated as neglected". His lobbying reportedly played a part in the enactment of the Aborigines Act 1911; this made him the legal guardian of every Aboriginal child in South Australia, including so-called "half-castes". Bringing Them Home,[48] a report on the status of the mixed race stated "... the physical infrastructure of missions, government institutions and children's homes was often very poor and resources were insufficient to improve them or to keep the children adequately clothed, fed, and sheltered".

In reality, during this period, removal of the mixed-race children was related to the fact that most were offspring of domestic servants working on pastoral farms,[49] and their removal allowed the mothers to continue working as help on the farm while at the same time removing the whites from responsibility for fathering them and from social stigma for having mixed-race children visible in the home.[50] Also, when they were left alone on the farm they became targets of the men who contributed to the rise in the population of mixed-race children.[51] The institutional racism was government policy gone awry, one that allowed babies to be taken from their mothers at birth, and this continued for most of the 20th century. That it was policy and kept secret for over 60 years is a mystery that no agency has solved to date.[52]

In the 1930s, the Northern Territory Protector of Natives, Cecil Cook, perceived the continuing rise in numbers of "half-caste" children as a problem. His proposed solution was: "Generally by the fifth and invariably by the sixth generation, all native characteristics of the Australian Aborigine are eradicated. The problem of our half-castes will quickly be eliminated by the complete disappearance of the black race, and the swift submergence of their progeny in the white". He did suggest at one point that they be all sterilised.[53]

Similarly, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, A. O. Neville, wrote in an article for The West Australian in 1930: "Eliminate in future the full-blood and the white and one common blend will remain. Eliminate the full-blood and permit the white admixture and eventually, the race will become white".[54]

Official policy then concentrated on removing all black people from the population,[55] to the extent that the full-blooded Aboriginal people were hunted to extinguish them from society,[56] and those of mixed race would be assimilated with the white race so that in a few generations they too would become white.[57]

By 1900, the recorded First Nations Australian population had declined to approximately 93,000.

Western Australia and Queensland specifically excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the electoral rolls. The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 excluded "Aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and Pacific Islands except for New Zealand" from voting unless they were on the roll before 1901.[58]

Land rights returned

In 1981, a land rights conference was held at James Cook University, where Eddie Mabo,[59] a Torres Strait Islander, made a speech to the audience in which he explained the land inheritance system on Murray Island.[60] The significance of this in terms of Australian common law doctrine was taken note of by one of the attendees, a lawyer, who suggested there should be a test case to claim land rights through the court system.[61] Ten years later, five months after Eddie Mabo died, on 3 June 1992, the High Court announced its historic decision, namely overturning the legal doctrine of terra nullius, which was the term applied by the British relating to the continent of Australia – "empty land".[62]

Public interest in the Mabo case had the side effect of throwing the media spotlight on all issues related to Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia, and most notably the Stolen Generations. The social impacts of forced removal have been measured and found to be quite severe. Although the stated aim of the "resocialisation" program was to improve the integration of Aboriginal people into modern society, a study conducted in Melbourne and cited in the official report found that there was no tangible improvement in the social position of "removed" Aboriginal people as compared to "non-removed", particularly in the areas of employment and post-secondary education.[63]

Most notably, the study indicated that removed Aboriginal people were actually less likely to have completed a secondary education, three times as likely to have acquired a police record and were twice as likely to use illicit drugs.[64] The only notable advantage "removed" Aboriginal people possessed was a higher average income, which the report noted was most likely due to the increased urbanisation of removed individuals, and hence greater access to welfare payments than for Aboriginal people living in remote communities.[65]

First Nations health and employment

In his 2008 address to the houses of parliament apologising for the treatment of the First Nations population, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a plea to the health services regarding the disparate treatment in health services. He noted the widening gap between the treatment of First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians, and committed the government to a strategy called "Closing the Gap", admitting to past institutional racism in health services that shortened the life expectancy of the Aboriginal people. Committees that followed up on this outlined broad categories to redress the inequities in life expectancy, educational opportunities and employment.[66] The Australian government also allocated funding to redress the past discrimination. First Nations Australians visit their general practitioners (GPs) and are hospitalised for diabetes, circulatory disease, musculoskeletal conditions, respiratory and kidney disease, mental, ear and eye problems and behavioural problems yet are less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to visit the GP, use a private doctor, or apply for residence in an old age facility. Childhood mortality rates, the gap in educational achievement and lack of employment opportunities were made goals that in a generation should halve the gap. A national "Close the Gap" day was announced for March of each year by the Human Rights Commission.[67]

In 2011, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that life expectancy had increased since 2008 by 11.5 years for women and 9.7 years for men along with a significant decrease in infant mortality, but it was still 2.5 times higher than for the non-indigenous population. Much of the health woes of the First Nations Australians could be traced to the availability of transport. In remote communities, the report cited 71% of the population in those remote Fist Nations communities lacked access to public transport, and 78% of the communities were more than 80 kilometres (50 miles) from the nearest hospital. Although English was the official language of Australia, many First Nations Australians did not speak it as a primary language, and the lack of printed materials that were translated into the Australian Aboriginal languages and the non-availability of translators formed a barrier to adequate health care for Aboriginal people. By 2015, most of the funding promised to achieve the goals of "Closing the Gap" had been cut, and the national group[68] monitoring the conditions of the First Nations population was not optimistic that the promises of 2008 will be kept.[69] In 2012, the group complained that institutional racism and overt discrimination continued to be issues, and that, in some sectors of government, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was being treated as an aspirational rather that a binding document.[70]Studies

The following studies are confined to Aboriginal peoples only, although not necessarily only true of those populations:

- A 2015 study showed that Aboriginal Australians have disproportionately high rates of severe physical disability, as much as three times that of non-Aboriginal Australians, possibly due to higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes and kidney disease. The study found that obesity and smoking rates were higher among Aboriginal people, which are contributing factors or causes of serious health issues. The study also showed that Aboriginal Australians were more likely to self-report their health as "excellent/very good" in spite of extant severe physical limitations.[71]

- One study reports that Aboriginal Australians are significantly affected by infectious diseases, particularly in rural areas. These diseases include strongyloidiasis, hookworm caused by Ancylostoma duodenale, scabies, and streptococcal infections. Because poverty is also prevalent in Aboriginal populations, the need for medical assistance is even greater in many Aboriginal Australian communities. The researchers suggested the use of mass drug administration (MDA) as a method of combating the diseases found commonly among Aboriginal peoples, while also highlighting the importance of "sanitation, access to clean water, good food, integrated vector control and management, childhood immunisations, and personal and family hygiene".[72]

- A study examining the psychosocial functioning of high-risk-exposed and low-risk-exposed Aboriginal Australians aged 12–17 found that in high-risk youths, personal well-being was protected by a sense of solidarity and common low socioeconomic status. However, in low-risk youths, perceptions of racism caused poor psychosocial functioning. The researchers suggested that factors such as racism, discrimination and alienation contributed to physiological health risks in ethnic minority families. The study also mentioned the effect of poverty on Aboriginal populations: higher morbidity and mortality rates.[73]

- Aboriginal Australians suffer from high rates of heart disease. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide and among Aboriginal Australians. Aboriginal people develop atrial fibrillation, a condition that sharply increases the risk of stroke, much earlier than non-Aboriginal Australians on average. The life expectancy for Aboriginal Australians is 10 years lower than non-Aboriginal Australians. Technologies such as the Wireless ambulatory ECG are being developed to screen at-risk individuals, particularly rural Australians, for atrial fibrillation.[74]

- According to Australian Journal Indigenous Issues three in four people regardless of ethnicity and beliefs hold a negative view of Indigenous Australians.

Housing

Throughout the entire rental system, from property procurement and investment prior to the search for a rental property, through to eviction, discrimination in the private rental sector (PRS) occurs.[75]

Indigenous Australians

Summarize

Perspective

Indigenous peoples of Australia, comprising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples, have lived in Australia for at least 65,000 years[76][77] before the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. The colonisation of Australia and development into a modern nation, saw explicit and implicit racial discrimination against Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians continue to be subjected to racist government policy and community attitudes. Racist community attitudes towards Aboriginal people have been confirmed as continuing both by surveys of Indigenous Australians[78] and self-disclosure of racist attitudes by non-Indigenous Australians.[79]

Since 2007, government policy considered to be racist include the Northern Territory Intervention which failed to produce a single child abuse conviction,[80] cashless welfare cards trialled almost exclusively in Aboriginal communities,[81] the Community Development Program that has seen Indigenous participants fined at a substantially higher rate than non-Indigenous participants in equivalent work-for-the-dole schemes,[82] and calls to shut down remote Indigenous communities[83] despite the United Nation's Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples specifying governments must facilitate the rights of Indigenous people to live on traditional land.

In 2016, police raids and behaviour on Palm Island following a death in custody were found to have breached the Racial Discrimination Act 1975,[84] with a record class action settlement of $30 million awarded to victims in May 2018.[85] The raids were found by the court to be "racist" and "unnecessary, disproportionate" with police having "acted in these ways because they were dealing with an Aboriginal community."[84]

Legal status

Despite Indigenous peoples being recognised under British common law as British subjects, with equal rights under the law, colonial government policy and public opinion treated Aboriginal peoples as inferior. The Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948, which came into force on 26 January 1949, created an Australian citizenship, but which co-existed with the continuing status of British subject. Aboriginal people became Australian citizens under the 1948 Act in the same way as other Australians, but they were not counted in the Australian population until after the 1967 referendum. The same applied to Torres Strait Islanders and the indigenous population of the Territory of Papua (then a part of Australia).

In 1770 and again in 1788, the British Empire claimed Eastern Australia as its own on the basis of the now discredited doctrine of terra nullius. The implication of the doctrine became evident when John Batman purported to make Batman's Treaty in 1835 with the Wurundjeri Elders of the area around the future Melbourne. Governor Bourke of New South Wales proclaimed the Treaty null and void and that indigenous Australians could not sell or assign land, nor could an individual person or group acquire it, other than through distribution by the Crown.[86] Though the so-called Treaty was objectionable on many grounds, it was the first, and until the 1990s, the only time that an attempt was made to deal directly with the Indigenous peoples.

Historical relations

English navigator James Cook claimed the east coast of Australia for the British Empire in 1770, without conducting negotiations with the existing inhabitants. The first Governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, was expressly instructed to establish friendship and good relations with Aboriginal people and interactions between the early settlers and the Indigenous people varied considerably throughout the colonial period – from the mutual curiosity displayed by the early interlocutors Bennelong and Bungaree of Sydney, to outright hostility of Pemulwuy and Windradyne of the Sydney region,[87] and Yagan around Perth. Bennelong and a companion became the first Australians to sail to Europe, where they met King George III. Bungaree accompanied the explorer Matthew Flinders on the first circumnavigation of Australia. Pemulwuy was accused of the first killing of a white settler in 1790, and Windradyne resisted colonial settlement beyond the Blue Mountains.[88]

With the establishment of European settlement and its subsequent expansion, the Indigenous populations were progressively forced into neighbouring territories,[citation needed] or subsumed into the new political entities of the Australian colonies. Violent conflict between Indigenous peoples and European settlers, described by some historians as frontier wars, arose out of this expansion: by the late 19th century, many Indigenous populations had been forcibly relocated to land reserves and missions. The nature of many of these land reserves and missions enabled disease to spread quickly and many were closed as resident numbers dropped, with the remaining residents being moved to other land reserves and missions in the 20th century.[89]

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, in Australia during the colonial period: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralisation".[90]

From the 1830s, colonial governments established the now controversial offices of the Protector of Aborigines in an effort to conduct government policy towards them. Christian churches sought to convert Aboriginal people, and were often used by government to carry out welfare and assimilation policies. Colonial churchmen such as Sydney's first Catholic archbishop, John Bede Polding, strongly advocated for Aboriginal rights and dignity[91] and prominent Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson, who was raised at a Lutheran mission in Cape York, has written that Christian missions throughout Australia's colonial history "provided a haven from the hell of life on the Australian frontier while at the same time facilitating colonisation".[92]

The Coniston massacre, which took place near the Coniston cattle station in the then Territory of Central Australia (now the Northern Territory) from 14 August to 18 October 1928, was the last known officially sanctioned massacre of Indigenous Australians and one of the last events of the Australian Frontier Wars.

The Caledon Bay crisis of 1932–34 saw one of the last incidents of violent interaction on the "frontier" of Indigenous and non-indigenous Australia, which began when the spearing of Japanese poachers who had been molesting Yolngu women was followed by the killing of a policeman. As the crisis unfolded, national opinion swung behind the Aboriginal people involved, and the first appeal on behalf of an Indigenous Australian to the High Court of Australia was launched. Following the crisis, the anthropologist Donald Thomson was dispatched by the government to live among the Yolngu.[93] Elsewhere around this time, activists like Sir Douglas Nicholls were commencing their campaigns for Aboriginal rights within the established Australian political system and the age of frontier conflict closed.

Frontier encounters in Australia were not universally negative. Positive accounts of Aboriginal customs and encounters are also recorded in the journals of early European explorers, who often relied on Aboriginal guides and assistance: Charles Sturt employed Aboriginal envoys to explore the Murray-Darling; the lone survivor of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition, John King, was helped by local Aboriginal people, and the famous tracker Jackey Jackey accompanied his ill-fated friend Edmund Kennedy to Cape York.[94] Respectful studies were conducted by such as Walter Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen in their renowned anthropological study The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899); and by Donald Thomson of Arnhem Land (c. 1935 – 1943). In inland Australia, the skills of Aboriginal stockmen became highly regarded and in the 20th century, Aboriginal stockmen like Vincent Lingiari became national figures in their campaigns for better pay and conditions.[95]

1938 was an important year for Indigenous rights campaigning. With the participation of leading indigenous activists like Douglas Nicholls, the Australian Aborigines Advancement League organised a protest "Day of Mourning" to mark the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet of British in Australia and launched its campaign for full citizenship rights for all Aboriginal people. In the 1940s, the conditions of life for Aboriginal people could be very poor. A permit system restricted movement and work opportunities for many Aboriginal people. In the 1950s, the government pursued a policy of "assimilation" which sought to achieve full citizenship rights for Aboriginal people but also wanted them to adopt the mode of life of other Australians (which very often was assumed to require suppression of cultural identity).[96]

World War II to the 2000s

The White Australia policy was dismantled in the decades following the Second World War and legal reforms undertaken to address indigenous disadvantage and establish land rights and native title.

In 1962, Robert Menzies' Commonwealth Electoral Act provided that all Indigenous people should have the right to enrol and vote at federal elections (prior to this, indigenous people in Queensland, Western Australia and "wards of the state" in the Northern Territory had been excluded from voting unless they were ex-servicemen). In 1965, Queensland became the last state to confer state voting rights on Aboriginal people, whereas in South Australia Aboriginal men had had the vote since the 1850s and Aboriginal women since the 1890s. A number of South Australian Aboriginal women took part in the vote selecting candidates for the constitutional conventions of the 1890s.[94][97] The 1967 referendum was held and overwhelmingly approved to amend the Constitution, removing discriminatory references and giving the national parliament the power to legislate specifically for Indigenous Australians.

In 1965, one of the earliest Aboriginal graduates from the University of Sydney, Charles Perkins, helped organise the Freedom Ride into parts of Australia to expose discrimination and inequality. In 1966, the Gurindji people of Wave Hill Station (owned by the Vestey Group) commenced strike action, known as the Gurindji strike, led by Vincent Lingiari, in a quest for equal pay and recognition of Indigenous land rights.[98]

From the 1960s, Australian writers began to re-assess European assumptions about Aboriginal Australia – with works including Alan Moorehead's The Fatal Impact (1966) and Geoffrey Blainey's landmark history Triumph of the Nomads (1975). In 1968, anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner described the lack of historical accounts of relations between European and Aboriginal people as "the great Australian silence".[99][100] Historian Henry Reynolds argues that there was a "historical neglect" of Aboriginal people by historians until the late 1960s.[101] Early commentaries often tended to describe Aboriginal people as doomed to extinction following the arrival of Europeans. William Westgarth's 1864 book on the colony of Victoria observed; "the case of the Aborigines of Victoria confirms ...it would seem almost an immutable law of nature that such inferior dark races should disappear."[102]

The Stolen Generations

The Stolen Generations were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian Federal and State government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments. The removals of those referred to as "half-caste" children were conducted in the period between approximately 1905[103] and 1967,[104][105] although in some places mixed-race children were still being taken into the 1970s.[106][107][108] Official government estimates are that in certain regions between one in ten and one in three Indigenous Australian children were forcibly taken from their families and communities between 1910 and 1970.

In April 2000, the Aboriginal Affairs Minister John Herron, presented a report in the Australian Parliament that questioned whether there had been a "Stolen Generation", arguing that only 10% of Aboriginal children had been removed, and they did not constitute an entire "generation". The report received media attention and there were protests against the claimed racism in this statement, and was countered by comparing use of this terminology to the World War 2 Lost Generation which also did not comprise an entire generation.[109] On 13 February 2008 Prime Minister Kevin Rudd presented an apology for the "Stolen Generation" as a motion in Parliament.[110][111]

Mabo Case

In 1992, the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in the Mabo Case, declaring the previous legal concept of terra nullius to be invalid. That same year, Prime Minister Paul Keating said in his Redfern Park Speech that European settlers were responsible for the difficulties Australian Aboriginal communities continued to face: "We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion. It was our ignorance and our prejudice". In 1999 Parliament passed a Motion of Reconciliation drafted by Prime Minister John Howard and Aboriginal Senator Aden Ridgeway naming mistreatment of Indigenous Australians as the most "blemished chapter in our international history".[112]

Current issues

In response to the Little Children are Sacred Report the Howard government launched the Northern Territory National Emergency Response in 2007, to reduce child molestation, domestic violence and substance abuse in remote Indigenous communities.[113] The measures of the response which have attracted most criticism comprise the exemption from the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, the compulsory acquisition of an unspecified number of prescribed communities (Measure 5) and the partial abolition of the permit system (Measure 10). These have been interpreted as undermining important principles and parameters established as part of the legal recognition of indigenous land rights in Australia.

The intervention, widely condemned as racist, failed to produce a single child abuse conviction in its first six years[80] Professor James Anaya, a United Nations Special Rapporteur, alleged in 2010 that the policy was "racially discriminating" because measures like banning alcohol and pornography and quarantining a percentage of welfare income for the purchase of essential goods represented a limitation on "individual autonomy".[114] The Rudd government, the Opposition and a number of prominent indigenous activists condemned Anaya's allegation. Central Australian Aboriginal leader Bess Price criticised the UN for not sending a female repporteur and said that Abaya had been led around by opponents of the intervention to meet with opponents of the intervention.[115][116]

In the early 21st century, much of Indigenous Australia continued to suffer lower standards of health and education than non-indigenous Australia. In 2007, the Close the Gap campaign was launched by Olympic champions Cathy Freeman and Ian Thorpe with the aim of achieving Indigenous health equality within 25 years.[117]

European Australians

Summarize

Perspective

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2024) |

Early British and Irish settlers

In the early decades of the establishment of British colonies in Australia, attitudes to race and ethnicity were imported from the British Isles. The ethnic mix of the early colonists consisted mainly of the four nationalities of the British Isles (English, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh), but also included some Jewish and black African convicts. Sectarianism, particularly anti-Irish-Catholic sentiment was initially enshrined in law, reflecting the difficult position of Irish people within the British Empire. One-tenth of all the convicts who came to Australia on the First Fleet were Catholic and at least half of them were born in Ireland. With Ireland often in revolt against British rule, the Irish enthusiasts of Australia faced surveillance and were denied the public practice of their religion in the early decades of settlement.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie served as the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales, from 1810 to 1821 and had a leading role in the social and economic development of New South Wales which saw it transition from a penal colony to a budding free society. He sought good relations with the Aboriginal population and upset British government opinion by treating emancipists as equal to free-settlers.[118] Soon after, the reformist attorney general, John Plunkett, sought to apply Enlightenment principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, first by extending jury rights to emancipists, then by extending legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and Aboriginal people. Plunkett twice charged the colonist perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre of Aboriginal people with murder, resulting in a conviction and his landmark Church Act of 1836 disestablished the Church of England and established legal equality between Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.[119]

While elements of sectarianism and anti- sentiment persisted into the 20th century in Australia, the integration of the Irish, English, Scottish and Welsh nationalities was one of the first notable successes of Australian immigration policy and set a pattern for later migrant intakes of suspicion of minorities giving way to acceptance.

Asian Australians

Summarize

Perspective

Early Asian and Pacific Islander immigration

The Australian colonies had passed restrictive legislation as early as the 1860s, directed specifically at Chinese immigrants. Objections to the Chinese originally arose because of their large numbers, their religious beliefs, the widespread perception that they worked harder, longer and far more cheaply than European Australians and the view that they habitually engaged in gambling and smoking opium. It was also felt they would lower living standards, threaten democracy and that their numbers could expand into a "yellow tide".[120] Later, a popular cry was raised against increasing numbers of Japanese (following Japan's victory over China in the Sino-Japanese War), South Asians and Kanakas (South Pacific islanders). Popular support for White Australia, always strong, was bolstered at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 when the Australian delegation led the fight to defeat a Japanese-sponsored racial-equality amendment to the League of Nations Covenant. The Japanese amendment was closely tied to their claim on German New Guinea and so was very largely refuted on security grounds.[121][122]

Buckland riot

The Buckland riot was an anti-Chinese race riot that occurred on 4 July 1857, in the goldfields of the Buckland Valley, Victoria, Australia, near present-day Porepunkah. At the time approximately 2000 Chinese and 700 European migrants were living in the Buckland area.[123]

Lambing Flat Riots

The Lambing Flat Riots (1860–1861) were a series of violent anti-Chinese demonstrations that took place in the Burrangong region, in New South Wales, Australia. They occurred on the goldfields at Spring Creek, Stoney Creek, Back Creek, Wombat, Blackguard Gully, Tipperary Gully, and Lambing Flat. Anti-Chinese sentiment was widespread during the Victorian gold rush.[124][125][126][127][128] This resentment manifested on 4 July 1857 when around 100 European rioters attacked Chinese settlements. The rioters had just left a public meeting at the Buckland Hotel where the riot ringleaders decided they would attempt to expel all the Chinese in the Buckland Valley. Contemporaneous newspaper reports claim that the riot was "led by Americans 'inflamed by liquor'".[129][130][131]

During the riot Chinese miners were beaten and robbed then driven across the Buckland River. At least three Chinese miners died reportedly of ill-health and entire encampments and a recently constructed Joss house were destroyed.[123]

Police arrested thirteen European accused rioters, however the empaneled juries acquitted all of major offences "amid the cheers of bystanders".[123][132] The verdicts of the juries were later criticised in the press.[133]

Events in the Australian goldfields in the 1850s led to hostility toward Chinese miners on the part of many Europeans, which was to affect many aspects of European-Chinese relations in Australia for the next century. Some of the sources of conflict between European and Chinese miners arose from the nature of the industry they were engaged in. Most gold mining in the early years was alluvial mining, where the gold was in small particles mixed with dirt, gravel and clay close to the surface of the ground, or buried in the beds of old watercourses or "leads". Extracting the gold took no great skill, but it was hard work, and generally speaking, the more work, the more gold the miner won. Europeans tended to work alone or in small groups, concentrating on rich patches of ground, and frequently abandoning a reasonably rich claim to take up another one rumoured to be richer. Very few miners became wealthy; the reality of the diggings was that relatively few miners found even enough gold to earn them a living.

Internment of Japanese and Taiwanese people in Australia during WWII

Historically, Taiwanese Australians have had a significant presence in Tatura and Rushworth, two neighbouring countryside towns respectively located in the regions of Greater Shepparton and Campaspe (Victoria), in the fertile Goulburn Valley.[134] During World War II, ethnic-Japanese (from Australia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific) and ethnic-Taiwanese (from the Netherlands East Indies) were interned nearby to these towns as a result of anti-espionage/collaboration policies enforced by the Australian government (and WWII Allies in the Asia-Pacific region).[135] Roughly 600 Taiwanese civilians (entire families, including mothers, children and the elderly) were held at "Internment Camp No. 4", located in Rushworth but nominally labeled as being part of the "Tatura Internment Group", between January 1942 and March 1946.[136] Most of the Japanese and Taiwanese civilians were innocent and had been arrested for racist reasons (see the related article "Internment of Japanese Americans", an article detailing similar internment in America).[137] Several Japanese and Taiwanese people were born in the internment camp and received British (Australian) birth certificates from a nearby hospital. Several Japanese people who were born in the internment camp were named "Tatura" in honour of their families' wartime internment at Tatura. During wartime internment, many working age adults in the internment camp operated small businesses (including a sewing factory) and local schools within the internment camp.[136] Regarding languages, schools mainly taught English, Japanese, Mandarin and Taiwanese languages (Hokkien, Hakka, Formosan). Filipinos are purported to have also been held at the camp, alongside Koreans, Manchus (possibly from Manchukuo), New Caledonians, New Hebrideans, people from the South Seas Mandate, people from Western New Guinea (and presumably also Papua New Guinea) and Aboriginal Australians (who were mixed-Japanese).[138][139]

After the war, internees were resettled in their country of ethnic origin, rather than their country of nationality or residence, with the exception of Japanese Australians, who were generally allowed to remain in Australia. Non-Australian Japanese, who originated from Southeast Asia and the Pacific, were repatriated to Occupied Japan. On the other hand, Taiwanese, most of whom originated from the Netherlands East Indies, were repatriated to Occupied Taiwan. The repatriation of Taiwanese during March 1946 caused public outcry in Australia due to the allegedly poor living conditions aboard the repatriating ship "Yoizuki", in what became known as the "Yoizuki Hellship scandal". Post-WWII, the Australian government was eager to expel any Japanese internees who did not possess Australian citizenship, and this included the majority of Taiwanese internees as well. However, the Republic of China (ROC) was an ally of Australia, and since the ROC had occupied Taiwan during October 1945, many among the Australian public believed that the Taiwanese internees should be deemed citizens of the ROC, and, therefore, friends of Australia, not to be expelled from the country, or at least not in such allegedly appalling conditions. This debate concerning the citizenship of Taiwanese internees—whether they were Chinese or Japanese—further inflamed public outrage at their allegedly appalling treatment by the Australian government. Additionally, it was technically true that several "camp babies"—internees who had been born on Australian soil whilst their parents were interned—possessed Australian birth certificates, which made them legally British subjects. However, many of these camp babies were also deported from the country alongside their non-citizen parents. There was also a minor controversy regarding the destination of repatriation, with some of the less Japan-friendly Taiwanese fearing that they would be repatriated to Japan, though this was resolved when they learnt that they were being repatriated to Taiwan instead.

On January 5, 1993, a plaque was erected at the site of the internment camp at Tatura (Rushworth) to commemorate the memory of wartime internment. Forty-six Japanese and Taiwanese ex-internees, as well as a former (Australian) camp guard, are listed on the plaque.[140]

Assaults against Indian students

Australia is a popular and longstanding destination for international students. End of year data for 2009 found that of the 631,935 international students enrolled in Australia, drawn from more than 217 different countries, some 120,913 were from India, making them the second largest group.[141] That same year, protests were conducted in Melbourne by Indian students and widescale media coverage in India alleged that a series of robberies and assaults against Indian students should be ascribed to racism in Australia.[141] According to a report tabled by the Overseas Indian Affairs Ministry, in all some 23 incidents were found to have involved "racial overtones" such as "anti Indian remarks".[142] In response, the Australian Institute of Criminology in consultation with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Department of Immigration and Citizenship sought to quantify the extent to which Indians were the subject of crime in Australia and found overall that international students as recorded victims of crime in Australia, were either "less likely" or "as likely" to be victims of physical assault and other theft, but that there was a "substantial over-representation of Indian students in retail/commercial robberies". The report found however that the proficiency of Indians in the English language and their consequent higher engagement in employment in the services sector ("including service stations, convenience stores, taxi drivers and other employment that typically involves working late night shifts alone and come with an increased risk of crime, either at the workplace or while travelling to and from work") was a more likely explanation for the crime rate differential than was any "racial motivation".[143]

On 30 May 2009, Indian students protested against what they claimed were racist attacks, blocking streets in central Melbourne. Thousands of students gathered outside the Royal Melbourne Hospital where one of the victims was admitted. The protest, however, was called off early on the next day morning after the protesters accused police of "ramrodding" them to break up their sit-in.[144] On 4 June 2009, China expressed concern over the matter – Chinese are the largest foreign student population in Australia with approximately 130,000 students.[145] In light of this event, the Australian Government started a Helpline for Indian students to report such incidents.[146] Australian High Commissioner to India John McCarthy said that there may have been an element of racism involved in some of the assaults reported upon Indians, but that they were mainly criminal in nature.[147] The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, termed these attacks "disturbing" and called for Australia to investigate the matters further.[148] In the aftermath of these attacks, other investigations alleged racist elements in the Victorian police force.[149]

However, in 2011, the Australian Institute of Criminology released a study entitled Crimes Against International Students:2005–2009.[150] This found that over the period 2005–2009, international students were statistically less likely to be assaulted than the average person in Australia. Indian students experienced an average assault rate in some jurisdictions, but overall they experienced lower assault rates than the Australian average. They did, however, experience higher rates of robbery, overall. The study could not sample incidents of crime that were not reported.[151] Additionally, multiple surveys of international students over the period of 2009–10 found a majority of Indian students felt safe.[152]

Current issues

Discrimination and violence against Asian Australians

Asian Australians have faced discrimination and racial violence based on their race and ethnicity.[153][154][155][156][157] Some Sikh Australians have experienced discrimination due to their religious garments being mistaken for those worn by Arabs or Muslims, particularly after the September 11 attacks.[158]

COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in anti-Asian[159] sentiment in Australia.[160][161][162][163][164][165][166][167]

Racial stereotypes

There are racial stereotypes that exist towards Asian Australians. Some view Asian Australians as "perpetual foreigners" and not as truly "Australian".[168]

Model minority

The term "model minority" refers to a minority group whose members are perceived to have achieved a higher level of socio-economic success than the population average.[169][170][171] In the case of Asian Australians, this stereotype is often applied to groups such as Chinese Australians, Indian Australians, and Korean Australians.[172][173] While it is true that some members of these groups have achieved success in education and income, it is important to note that the model minority stereotype is an oversimplification that ignores the diversity and challenges faced by individuals within these groups.[174][175][176]

Bamboo ceiling

The bamboo ceiling is a term used to describe the barriers that prevent Asian Australians from achieving leadership positions in the workplace.[177][178][179][180] Despite making up 9.3 percent of the Australian labour force, Asian Australians are significantly underrepresented in senior executive positions, with only 4.9 percent achieving these roles.[181][182][178] This disparity is often attributed to unconscious bias and discrimination within the workplace.[183][184][185]

Disparities among Asian Australians

There are social and economic disparities among Asian Australians. While Asian Australians are over-represented in high-performing schools and university courses, some ethnic groups face challenges.[186][173][187][188] For example, Cambodian Australians have lower rates of educational qualifications and higher participation in semi-skilled and unskilled occupations compared to the general Australian population.[189][190][191] Laotian Australians also have lower rates of higher non-school qualifications and higher unemployment rates compared to the total Australian population.[192]

Vietnamese Australians have slightly lower participation in the labour force and higher unemployment rates compared to the national average.[193] Hmong Australians have historically had high unemployment rates and a large proportion in unskilled factory jobs, though this has improved somewhat in recent years.[194] In contrast, Bangladeshi Australians have higher educational levels and a higher participation in skilled managerial, professional, or trade occupations compared to the total Australian population.[195]Middle Eastern Australians

Summarize

Perspective

Cronulla riots

The Cronulla riots of 2005[196] were a series of racially motivated mob confrontations which originated in and around Cronulla, a beachfront suburb of Sydney, New South Wales. Soon after the riot, ethnically motivated violent incidents occurred in several other Sydney suburbs.[citation needed]

On Sunday, 11 December 2005, approximately 5,000 people gathered to protest against alleged incidents of assaults and intimidatory behaviour by groups of Middle Eastern-looking youths from the suburbs of South Western Sydney. The crowd initially assembled without incident, but violence broke out after a large segment of the mostly white[197] crowd chased a man of Middle Eastern appearance into a hotel and two other youths of Middle Eastern appearance were assaulted on a train.[citation needed]

The following nights saw several retaliatory violent assaults in the communities near Cronulla and Maroubra, with large gatherings around south western Sydney, and an unprecedented police lock-down of Sydney beaches and surrounding areas, between Wollongong and Newcastle.[citation needed]

SBS / Al Jazeera (for Al Jazeera) explores these events in 2013 (2015) four-part documentary series "Once Upon a Time in Punchbowl", specifically in last two episodes, "Episode three, 2000–2005" and "Episode four, 2005-present".[198]

In 2012, shock jock Alan Jones lost an appeal against charges that he deliberately incited the riots on his 2GB radio show.[199]

African Australians

Summarize

Perspective

African Australian people suffer a high degree of racial discrimination,[200][201][202][203] with the 2018 Australian Human Rights Commission report stating "the five groups that experienced the highest level of racial discrimination were those born in South Sudan, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Ethiopia and those who identified as Indigenous."[200][203]

Australia has a long history of official and unofficial racism towards black Africans, reflected in the White Australia policy, in effect from 1901 until the nineteen-seventies, which prohibited the immigration of black Africans, among other non-White groups.[200][204] Prior to the policy's implementation, small numbers of black Africans and African-Americans were resident in Australia, and their presence was explicitly mentioned in the discussions on the restriction of non-white immigration.[200]

Following the end of this policy, despite Australia becoming more ethnically diverse, negative stereotypes around black Africans remained prominent in Australian culture.[200][203][204] Modern African-Australians are culturally and socially diverse, but Australian society typically views them as a homogenous group, set in opposition to its constructions of whiteness.[200] In Australia, "Africanness" is associated with a lack of civilisation, disease, dirt, war and poverty, and scholars such as Wearing, Jakubowicz, Wickes and others note that this perception is rooted in a social context of racist and discriminatory assumptions about black people.[200]

Current academic literature has highlighted frequent experiences of discrimination, criminalisation and racialisation shaping the interactions of black-African Australians with majority society.[200] In particular, a strong negative association between Africanness and criminality exists in Australian culture, which was reflected in the media's presentation of the events in Melbourne.[200]

The 2016 Challenging Racism Project found negative attitudes to black people were common in Australia. 21% of respondents felt that African refugees increased crime in Australia, and 16.1% stated they felt "very negative or somewhat negative" towards African Australians.[200] Wickes et al argue that these attitudes reflect implicit biases widespread in Australia which can cause unconscious discrimination.[200] International Studies scholar, Mandisi Majavu also identifies a tendency to identify African Australian men as "towering seven feet 'brutes'" associated with "backwardness, primitiveness, danger and crime" and states that blackness is a source of fear in some whites. [203] Examples of this include a ban on Sudanese students congregating in groups of more than three in Melbourne schools for fear that they may seem threatening.[203]

Australian academics, Kathomi Gatwiri and Leticia Anderson argue that African Australians are defined as "perpetual strangers" within Australian society, and as such are constructed as a threat, sometimes within rhetoric of a "clash of civilisations".[204]

The prejudices prevalent against African Australians gave rise to a moral panic between 2016-2018.[204][200][203] During this period, members of the Coalition government and the right-wing press focussed continual attention on an alleged "African gang problem" in Melbourne, despite repeated denials that any such gangs existed by senior members of the police, members of the Sudanese Australian community in the city, and the Victorian government.[204][200][203]

Contemporary issues

Summarize

Perspective

Asylum seekers

Commentators such as writer Christos Tsiolkas have accused the Australian Government of racism in its approach to asylum seekers in Australia. Both major parties have supported a ban on asylum seekers who arrive by boat.[205] For many years Australia operated the Pacific Solution, which included the relocation of asylum seekers arriving by boat in offshore detention centres on Manus and Nauru.[206] Social justice advocates and international organisations such as Amnesty International have condemned Australia's policies, with one describing them as "an appeal to fear and racism".[207]

Anti-Semitism in Australia

From 2013 to 2017 over 673 incidents of anti-Semitic behaviour were reported,[208] with an increase of such incidents in recent years.[209] Incidents include spitting, such as a woman in her 60s who was spat on after being called "Jewish scum".[210]

Far-right and neo-Nazi groups

The 21st century has seen the creation of several groups with racist manifestos in Australia, from street gangs (Australian Defence League) through loosely grouped protest groups (Reclaim Australia) to far-right political parties (Fraser Anning's Conservative National Party). The ideology of the Antipodean Resistance, a neo-Nazi clan headquartered in Melbourne, is based on homophobia, anti-Semitism, white supremacism and Australian nationalism.[211] Some groups, such as the True Blue Crew, are committed to violence.[212][213] The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) monitors this and other groups for signs of far-right terrorism.[214]

The National Socialist Network (NSN) was formed by members of the Lads Society and Antipodean Resistance in late 2020. It is a neo-Nazi group headquartered in Melbourne.

Pauline Hanson and One Nation

Senator Pauline Hanson, in her 1998 maiden speech to Parliament called for the abolition of multiculturalism and said that "reverse racism" was being applied to "mainstream Australians" who were not entitled to the same welfare and government funding as minority groups. She has said that Australia was in danger of being "swamped by Asians", and that these immigrants "have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate". She was widely accused of racism.[215] In 2006, she achieved notoriety by asserting that Africans bring disease into Australia.[216] In June 2021, following media reports that the proposed national curriculum was "preoccupied with the oppression, discrimination and struggles of Indigenous Australians", Hanson tabled a motion in the Australian Senate calling on the federal government to reject critical race theory (CRT), despite it not being included in the curriculum.[217]

Alleviation

Summarize

Perspective

Western Sydney, a suburban region with a long history of migrant settlement, became one of the first regions in Australia to enact public planning to counter cultural racism.[218]

In 2020, the Victorian Government set up an Anti-Racism Taskforce, designed to advise and consider issues such as unconscious bias, privilege, and how race intersects with other forms of discrimination, as well as how racism manifests through employment and in access to services.[219]

Re-directing ingroup bias

Several possibilities exist for how to combat aversive racism. One method looks to the cognitive foundations of prejudice. The basic socio-cognitive process of creating in-groups and out-groups is what leads many to identify with their own race while feeling averted to other races, or out-group members. According to the common ingroup identity model inducing individuals to recategorize themselves and others as part of a larger, superordinate group can lead to more positive attitudes towards members of a former out-group.[220] Research has shown this model to be effective.[221] This shows that changing the in-group criteria from race to something else that includes both groups, implicit biases can be diminished. This does not mean that each group has to necessarily relinquish subgroup identities. According to the common ingroup identity model, individuals can retain their original identity while simultaneously harboring a larger more inclusive identity – a dual identity representation.[220]

Acknowledging and addressing unconscious bias

Other research has indicated that, although often preferred by explicitly nonprejudiced people and seen to be an egalitarian approach, adopting a "colorblind" approach to interracial interactions has actually proven to be detrimental. While minorities often prefer to have their racial identity recognized, people who employ the "colorblind" approach can generate greater feelings of distrust and impressions of prejudice in interracial interactions.[222] Thus, embracing diversity, rather than ignoring the topic, can be seen as one way of improving these interactions.

The research of Monteith and Voils has demonstrated that, in aversively racist people, the recognition of disparity between their personal standards and their actual behaviors can lead to feelings of guilt, which in turn causes them to monitor their prejudicial behaviors and perform them less often.[223] Furthermore, when practiced consistently, these monitored behaviors become less and less disparate from the personal standards of the individual, and can eventually even suppress negative responses that were once automatic. This is encouraging, as it suggests that the good intentions of aversively racist people can be used to help eliminate their implicit prejudices.

Some research has directly supported this notion. In one study, people who scored nonprejudiced (low explicit and implicit racism scores) and as aversively racist people (low explicit but high implicit racism scores) were placed in either a hypocrisy or a control condition. Those in the hypocrisy condition were made to write about some time they had been unfair or prejudiced towards an Asian person, while those in the control group were not. They were then asked to make recommendations for funding to the Asian Students Association. Aversively racist participants in the hypocrisy group made much larger funding recommendations (the highest of any of the four groups, actually) than the aversively racist people in the control group. The nonprejudiced participants, on the other hand, displayed no significant difference in funding recommendations, whether they were in the hypocrisy group or the control group.[224] In another study measuring the correction of implicit bias among aversively racist people, Green et al. examined physicians' treatment recommendations for blacks and whites.[225] While aversively racist people typically recommended an aggressive treatment plan more often for white than for black patients, those who were made aware of the possibility that their implicit biases could be informing their treatment recommendations did not end up showing such a disparity in their treatment plans.

While all of the above-mentioned studies attempt to address the nonconscious process of implicit racism through conscious thought processes and self-awareness, others have sought to combat aversive racism through altering nonconscious processes. In the same way that implicit attitudes can be learned through sociocultural transmission, they can be "unlearned". By making individuals aware of the implicit biases affecting their behavior, they can take steps to control automatic negative associations that can lead to discriminatory behavior. A growing body of research has demonstrated that practice pairing minority racial out-groups with counter-stereotypic examples can reduce implicit forms of bias.[226] Moskowitz, Salomon and Taylor found that people with egalitarian attitudes responded faster to egalitarian words after being shown an African-American face, relative to a white face.[227] In later research, it was shown that when primed in such a way as to motivate egalitarian behaviors, stereotype-relevant reactions were slower, but notably, these reactions were recorded at speeds too fast to have been consciously controlled, indicating an implicit bias shift, rather than explicit.[228]

One very interesting finding may have implied that aversive racism can be combated simply by eliminating the desire to employ the time- and energy-saving tactic of stereotyping. By priming and inducing participants' creativity, which causes people to avoid leaning on their energy-saving mental shortcuts, such as stereotyping, reduced participants' propensity to stereotype.[229]

Finally, there is evidence to suggest that simply having a greater amount of intergroup contact is associated with less implicit intergroup bias.[230]Closing the Gap

The Closing the Gap framework is a strategy by the Commonwealth and state and territory governments of Australia that aims to reduce disparity between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians on key health, education and economic opportunity targets. The strategy was launched in 2008 in response to the Close the Gap social justice movement, and revised in 2020 with additional targets and a refreshed strategy.

The Closing the Gap targets relate to life expectancy, child mortality, access to early childhood education, literacy and numeracy at specified school levels, Year 12 attainment, school attendance, and employment outcomes. Annual Closing the Gap reports are presented to federal parliament, providing updates on the agreed targets and related topics. The Closing the Gap Report 2019 reported that of the seven targets, only two – early childhood education and Year 12 attainment – had been met. The remaining targets are not on track to be met within their specified time-frames.

From the adoption of the framework in 2008 until 2018, the federal and state and territory governments worked together via the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) on the framework, with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet producing a report at the end of each year analysing progress on each of its seven targets.

In 2019, the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) was established and took over reporting and high-level strategy responsibilities. The NIAA works in partnership with the Coalition of Peaks, which represents Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, as well as state and territory governments and the Australian Local Government Association, to deliver strategy outcomes.Uluru Statement from the Heart

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is a 2017 petition to the people of Australia, written and endorsed by the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders selected as delegates to the First Nations National Constitutional Convention. The document calls for substantive constitutional change and structural reform through the creation of two new institutions; a constitutionally protected First Nations Voice and a Makarrata Commission[a], to oversee agreement-making and truth-telling between governments and First Nations. Such reforms should be implemented, it is argued, both in recognition of the continuing sovereignty of Indigenous peoples and to address structural power differences that has led to severe disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. These reforms can be summarised as Voice, Treaty and Truth.

In October 2017, the then Coalition government rejected the Voice proposal, characterising it as a "radical" constitutional change that would not be supported by a majority of Australians in a referendum. Following this, in May 2022 Labor leader Anthony Albanese endorsed the Uluru Statement on the occasion of his 2022 election victory and committed to implementing it in full. However, the Voice was rejected at a subsequent referendum in 2023, with the government noting that further action on Treaty and Truth will take some time.[231]Legislation relating to racism

Summarize

Perspective

Racist legislation in Australian history

Some notable legislation which has been claimed to have been based on racist theories include:

- The Immigration Restriction Act 1901, to prescribe where migrants to Australia were accepted from (this in part became the basis for the White Australia Policy). This law effectively prevented almost all immigration from Asia for approximately 50 years.

- The Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, a law designed to facilitate the deportation of Pacific Island workers (then known as "Kanakas") from Australia. These workers were originally from Melanesia and were sent to work on farms in Queensland. Descendants of the workers that remained in Australia are today known as South Sea Islanders.

- The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 gave women the vote across all states, but allowed states to restrict voting rights for "natives" (i.e Indigenous Australians).

Anti-racist legislation in contemporary Australia

The following constituted important legal reforms in the movement towards racial equality:

- 1958 revision of the Migration Act, introduced a simpler system for entry and abolished the "dictation test".

- 1962 Commonwealth Electoral Act, provided that all Indigenous Australians should have the right to enrol and vote at federal elections (previously this right had been restricted in some states other than for Aboriginal ex-servicemen, who secured the right to vote in all states under 1949 legislation).

- Migration Act 1966, effectively dismantled the White Australia Policy and increased access to non-European migrants.

- Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, was a significant step in legal recognition of Aboriginal land ownership.[232]

The following Australian Federal and State legislation relates to racism and discrimination:

- Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975

- Commonwealth Racial Hatred Act (1995)

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act (1986)

- New South Wales: Anti-Discrimination Act (1977)

- South Australia: Prohibition of Discrimination Act 1966 (SA) under Don Dunstan,[233] then Attorney-General of South Australia (now Equal Opportunity Act (1984)) and Racial Vilification Act (1996). The Prohibition of Discrimination Act 1966 (SA) made race discrimination on the basis of skin colour and country of origin and in circumstances such as the provision of food, drink, services and accommodation and in the termination of employment a criminal offence.

- Western Australia: Equal Opportunity Act (1984) and Criminal Code

- Australian Capital Territory: Discrimination Act (1991)

- Queensland: Anti-Discrimination Act (1991)

- Northern Territory: Anti-Discrimination Act (1992)

- Victoria: Equal Opportunity Act (1995) and Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001

- Tasmania: Anti-Discrimination Act (1998)

See also

- Aboriginal deaths in custody

- George Floyd protests in Australia

- Institutional racism

- Institutional racism in Australia

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Racism by country

- RacismNotWelcome, a grassroots campaign

- Racial violence in Australia

- White privilege in Australia

- Initiatives by South Australian Premier Don Dunstan

Indigenous advocates

- Linda Burney, MP

- Pat Dodson

- Adam Goodes, AFL player

- Stan Grant (Wiradjuri elder)

- Stan Grant (journalist)

- June Oscar

- Nova Peris

- Nicky Winmar

- Ken Wyatt

- Don Dunstan, former Premier of South Australia

Notes

- "Makarrata" is a Yolngu word "describing a process of conflict resolution, peacemaking and justice", or "a coming together after a struggle".

References

Bibliography

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.