Formosan languages

Austronesian languages of Taiwan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Formosan languages are a geographic grouping comprising the languages of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, all of which are Austronesian. They do not form a single subfamily of Austronesian but rather up to nine separate primary subfamilies. The Taiwanese indigenous peoples recognized by the government are about 2.3% of the island's population. However, only 35% speak their ancestral language, due to centuries of language shift.[2] Of the approximately 26 languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples, at least ten are extinct, another four (perhaps five) are moribund,[3][4] and all others are to some degree endangered. They are national languages of Taiwan.[5]

| Formosan | |

|---|---|

| (geographic) | |

| Geographic distribution | Taiwan |

| Ethnicity | Taiwanese Aborigines (Formosan people) |

| Linguistic classification | Austronesian

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-5 | fox |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

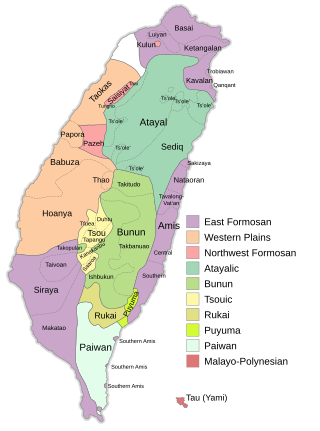

Families of Formosan languages before Chinese colonization, per Blust (1999). Malayo-Polynesian (red) may lie within Eastern Formosan (purple).

The white section is unattested; some maps fill it in with Luiyang, Kulon or as generic 'Ketagalan'.[1] | |

The aboriginal languages of Taiwan have great significance in historical linguistics since, in all likelihood, Taiwan is the place of origin of the entire Austronesian language family. According to American linguist Robert Blust, the Formosan languages form nine of the ten principal branches of the family,[6] while the one remaining principal branch, Malayo-Polynesian, contains nearly 1,200 Austronesian languages found outside Taiwan.[7] Although some other linguists disagree with some details of Blust's analysis, a broad consensus has coalesced around the conclusion that the Austronesian languages originated in Taiwan,[8] and the theory has been strengthened by recent studies in human population genetics.[9]

Recent history

All Formosan languages are slowly being replaced by the culturally dominant Taiwanese Mandarin. In recent decades the Taiwan government started an aboriginal reappreciation program that included the reintroduction of Formosan first languages in Taiwanese schools. However, the results of this initiative have been disappointing.[10]

In 2005, in order to help with the preservation of the languages of the indigenous people of Taiwan, the council established a Romanized writing system for all of Taiwan's aboriginal languages. The council has also helped with classes and language certification programs for members of the indigenous community and the non-Formosan Taiwanese to help the conservation movement.[11]

Classification

Formosan languages form nine distinct branches of the Austronesian language family (with all other Malayo-Polynesian languages forming the tenth branch of the Austronesian).

List of languages

Summarize

Perspective

It is often difficult to decide where to draw the boundary between a language and a dialect, causing some minor disagreement among scholars regarding the inventory of Formosan languages. There is even more uncertainty regarding possible extinct or assimilated Formosan peoples. Frequently cited examples of Formosan languages are given below,[12] but the list should not be considered exhaustive.

Living languages

| Language | Code | No. of dialects | Dialects | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amis | ami | 5 | 'Amisay a Pangcah, Siwkolan, Pasawalian, Farangaw, Palidaw | |

| Atayal | tay | 6 | Squliq, Skikun, Ts'ole', Ci'uli, Mayrinax, Plngawan | high dialect diversity, sometimes considered separate languages |

| Bunun | bnn | 5 | Takitudu, Takibakha, Takivatan, Takbanuaz, Isbukun | high dialect diversity |

| Kanakanavu | xnb | 1 | moribund | |

| Kavalan | ckv | 1 | listed in some sources[3] as moribund, though further analysis may show otherwise[13] | |

| Paiwan | pwn | 4 | Eastern, Northern, Central, Southern | |

| Puyuma | pyu | 4 | Puyuma, Katratripul, Ulivelivek, Kasavakan | |

| Rukai | dru | 6 | Ngudradrekay, Taromak Drekay, Teldreka, Thakongadavane, 'Oponoho | |

| Saaroa | sxr | 1 | moribund | |

| Saisiyat | xsy | 1 | ||

| Sakizaya | szy | 1 | ||

| Seediq | trv | 3 | Tgdaya, Toda, (Truku) | |

| Thao | ssf | 1 | moribund | |

| Truku | trv | 1 | ||

| Tsou | tsu | 1 | ||

| Yami/Tao | tao | 1 | also called Tao. Linguistically, not a member of the "Formosan languages", but a Malayo-Polynesian language. |

- Although Yami is geographically in Taiwan, it is not classified as Formosan in linguistics.

Extinct languages

| Language | Code | No. of dialects | Dialects | Extinction date & notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basay | byq | 1 | Mid-20th century | |

| Babuza | bzg | 3? | Babuza, Takoas, Favorlang (?). | Late 19th century. Ongoing revival efforts. |

| Kulon | uon | 1 | Mid-20th century | |

| Pazeh | pzh | 2 | Pazeh, Kaxabu | 2010. Ongoing revival efforts. |

| Ketagalan | kae | 1 | Mid-20th century | |

| Papora | ppu | 2? | Papora, Hoanya (?). | |

| Siraya | fos | 2? | Siraya, Makatao (?). | Late 19th century. Ongoing revival efforts. |

| Taivoan | tvx | 1 | Late 19th century. Ongoing revival efforts. |

Grammar

Verbs typically are not inflected for person or number, but do inflect for tense, mood, voice and aspect. Formosan languages are unusual in their use of the symmetrical voice, in which a noun is marked with the direct case while the verb affix indicates its role in the sentence. This can be seen as a generalisation of the active and passive voices, and is considered a unique morphosyntactic alignment. Furthermore, adverbs are not a unique category of words, but are instead expressed by coverbs.

Nouns are not marked for number and do not have grammatical gender. Noun cases are typically marked by particles rather than inflecting the word itself.

In terms of word order, most Formosan languages display verb-initial word order—VSO (verb-subject-object) or VOS (verb-object-subject)—with the exception of some Northern Formosan languages, such as Thao, Saisiyat, and Pazih, possibly from influence from Chinese.

Li (1998) lists the word orders of several Formosan languages.[14]

- Rukai: VSO, VOS

- Tsou: VOS

- Bunun: VSO

- Atayal: VSO, VOS

- Saisiyat: VS, SVO

- Pazih: VOS, SVO

- Thao: VSO, SVO

- Amis: VOS, VSO

- Kavalan: VOS

- Puyuma: VSO

- Paiwan: VSO, VOS

Sound changes

Summarize

Perspective

Tanan Rukai is the Formosan language with the largest number of phonemes with 23 consonants and 4 vowels containing length contrast, while Kanakanavu and Saaroa have the fewest phonemes with 13 consonants and 4 vowels.[15]

Wolff

The tables below list the Proto-Austronesian reflexes of individual languages given by Wolff (2010).[16]

| Proto-Austronesian | Pazih | Saisiat | Thao | Atayalic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *p | p | p | p | p |

| *t | t, s | t, s, ʃ | t, θ | t, c (s) |

| *c | z [dz] | h | t | x, h |

| *k | k | k | k | k |

| *q | Ø | ʔ | q | q, ʔ |

| *b | b | b | f | b- |

| *d | d | r | s | r |

| *j | d | r | s | r |

| *g | k-, -z- [dz], -t | k-, -z- [ð], -z [ð] | k-, -ð-, -ð | k-[17] |

| *ɣ | x | l [ḷ] (> Ø in Tonghœʔ) | ɬ | ɣ, r, Ø |

| *m | m | m | m | m |

| *n | n | n | n | n |

| *ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | n | ŋ |

| *s | s | ʃ | ʃ | s |

| *h | h | h | Ø | h |

| *l | r | l [ḷ] (> Ø in Tonghœʔ) | r | l |

| *ɬ | l | ɬ | ð | l |

| *w | w | w | w | w |

| *y | y | y | y | y |

| Proto-Austronesian | Saaroa | Kanakanavu | Rukai | Bunun | Amis | Kavalan | Puyuma | Paiwan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p |

| *t | t, c | t, c | t, c | t | t | t | t, ʈ | tj [č], ts [c] |

| *c | s, Ø | c | θ, s, Ø | c ([s] in Central & South) | c | s | s | t |

| *k | k | k | k | k | k | k, q | k | k |

| *q | Ø | ʔ | Ø | q (x in Ishbukun) | ɦ | Ø | ɦ | q |

| *b | v | v [β] | b | b | f | b | v [β] | v |

| *d | s | c | ḍ | d | r | z | d, z | dj [j], z |

| *j | s | c | d | d | r | z | d, z | dj [j], z |

| *g | k-, -ɬ- | k-, -l-, -l | g | k-, -Ø-, -Ø | k-, -n-, -n | k-, -n-, -n | h-, -d-, -d | g-, -d-, -d |

| *ɣ | r | r | r, Ø | l | l [ḷ] | ɣ | r | Ø |

| *m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m |

| *n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| *ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ |

| *s | Ø | s | s | s | s | Ø | Ø | s |

| *h | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | h | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| *l | Ø | Ø, l | ñ | h-, -Ø-, -Ø | l [ḷ] | r, ɣ | l [ḷ] | l |

| *ɬ | ɬ | n | ɬ | n | ɬ | n | ɬ | ɬ |

| *w | Ø | Ø | v | v | w | w | w | w |

| *y | ɬ | l | ð | ð | y | y | y | y |

| Proto-Austronesian | Tagalog | Chamorro | Malay | Old Javanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *p | p | f | p | p |

| *t | t | t | t | t |

| *c | s | s | s | s |

| *k | k | h | k | k |

| *q | ʔ | ʔ | h | h |

| *b | b | p | b, -p | b, w |

| *d | d-, -l-, -d | h | d, -t | ḍ, r |

| *j | d-, -l-, -d | ch | j, -t | d |

| *g | k-, -l-, -d | Ø | d-, -r-, -r | g-, -r-, -r |

| *ɣ | g | g | r | Ø |

| *m | m | m | m | m |

| *n | n | n | n | n |

| *ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ |

| *s | h | Ø | h | h |

| *h | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| *l | l | l | l | l |

| *ɬ | n | ñ, n, l | l-/ñ-, -ñ-/-n-, -n | n |

| *w | w | w | Ø, w | w |

| *y | y | y | y | y |

Blust

The following table lists reflexes of Proto-Austronesian *j in various Formosan languages (Blust 2009:572).

| Language | Reflex |

|---|---|

| Tsou | Ø |

| Kanakanavu | l |

| Saaroa | ɬ (-ɬ- only) |

| Puyuma | d |

| Paiwan | d |

| Bunun | Ø |

| Atayal | r (in Squliq), g (sporadic), s (sporadic) |

| Sediq | y (-y- only), c (-c only) |

| Pazeh | z ([dz]) (-z- only), d (-d only) |

| Saisiyat | z ([ð]) |

| Thao | z ([ð]) |

| Amis | n |

| Kavalan | n |

| Siraya | n |

The following table lists reflexes of Proto-Austronesian *ʀ in various Formosan languages (Blust 2009:582).

| Language | Reflex |

|---|---|

| Paiwan | Ø |

| Bunun | l |

| Kavalan | ʀ (contrastive uvular rhotic) |

| Basay | l |

| Amis | l |

| Atayal | g; r (before /i/) |

| Sediq | r |

| Pazeh | x |

| Taokas | l |

| Thao | lh (voiceless lateral) |

| Saisiyat | L (retroflex flap) |

| Bashiic (extra-Formosan) | y |

Lenition patterns include (Blust 2009:604-605):

- *b, *d in Proto-Austronesian

- *b > f, *d > c, r in Tsou

- *b > v, *d > d in Puyuma

- *b > v, *d > d, r in Paiwan

- *b > b, *d > r in Saisiyat

- *b > f, *d > s in Thao

- *b > v, *d > r in Yami (extra-Formosan)

Distributions

Gallery

Information

Li (2001) lists the geographical homelands for the following Formosan languages.[18]

- Tsou: southwestern parts of central Taiwan; Yushan (oral traditions)

- Saisiyat and Kulon: somewhere between Tatu River and Tachia River not far from the coast

- Thao: Choshui River

- Qauqaut: mid-stream of Takiri River (Liwuhsi in Chinese)

- Siraya: Chianan Plains

- Makatau: Pingtung

- Bunun: Hsinyi (信義鄉) in Nantou County

- Paiwan: Ailiao River, near the foot of the mountains

See also

- Cognate sets for Formosan languages (Wiktionary)

- Demographics of indigenous Taiwanese

- Writing systems of Formosan languages

- Personal pronoun systems of Formosan languages

- Fossilized affixes in Austronesian languages

- Proto-Austronesian language

- Tsou language for an example of the unusual phonotactics of the Formosan languages

- Sinckan Manuscripts

- Naming customs of Taiwanese indigenous peoples

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.