The Stramenopiles, also called Heterokonts, are a clade of organisms distinguished by the presence of stiff tripartite external hairs. In most species, the hairs are attached to flagella, in some they are attached to other areas of the cellular surface, and in some they have been secondarily lost (in which case relatedness to stramenopile ancestors is evident from other shared cytological features or from genetic similarity). Stramenopiles represent one of the three major clades in the SAR supergroup, along with Alveolata and Rhizaria.

| Stramenopiles Temporal range: Late Mesoproterozoic-present, | |

|---|---|

| |

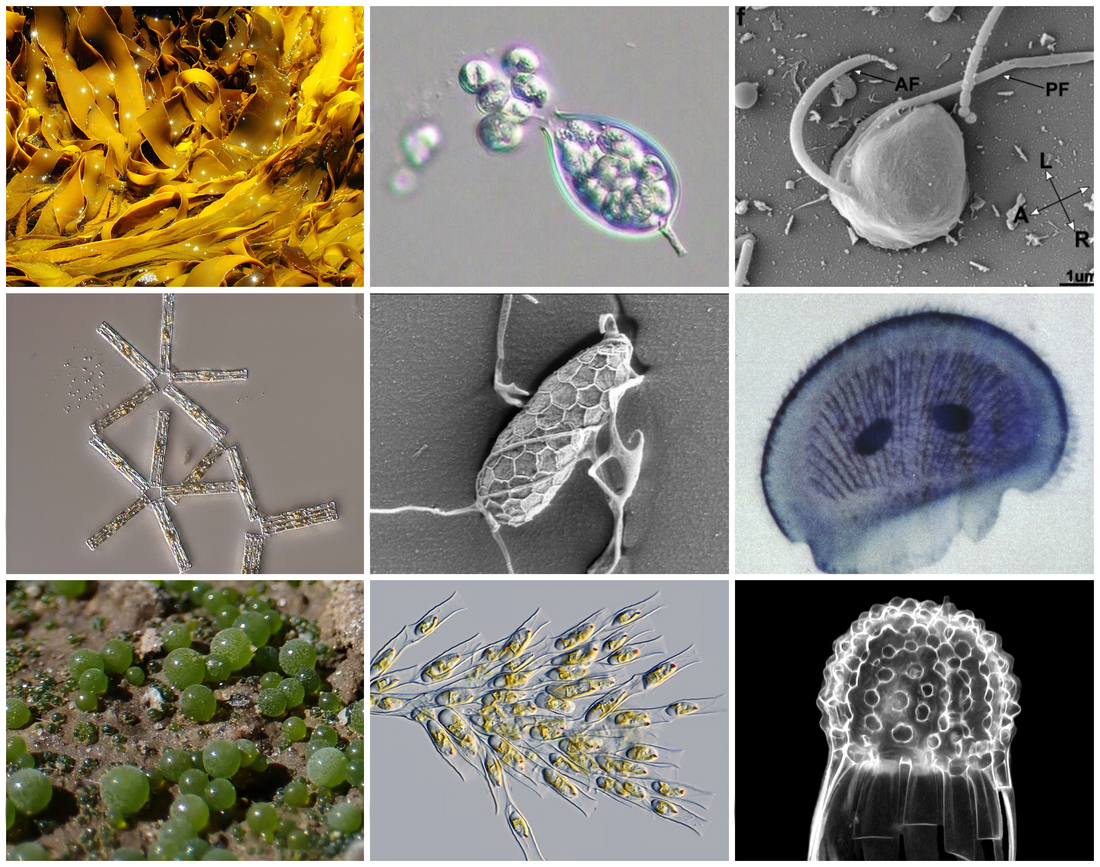

| Diversity of stramenopiles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Stramenopiles Patterson 1989[2] emend. Adl et al. 2005[3] |

| Phyla and subphyla[4] | |

| Diversity | |

| >100000 species[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Stramenopiles are eukaryotes; most are single-celled, but some are multicellular including some large seaweeds, the brown algae. The group includes a variety of algal protists, heterotrophic flagellates, opalines and closely related proteromonad flagellates (all endobionts in other organisms); the actinophryid heliozoa, and oomycetes. The tripartite hairs characteristic of the group have been lost in some of the included taxa – for example in most diatoms.

Many stramenopiles are unicellular flagellates, and most others produce flagellated cells at some point in their lifecycles, for instance as gametes or zoospores. Most flagellated heterokonts have two flagella; the anterior flagellum has one or two rows of stiff hairs or mastigonemes, and the posterior flagellum is without such embellishments, being smooth, usually shorter, or in a few cases not projecting from the cell.

The term 'heterokont' is used both as an adjective – indicating that a cell has two dissimilar flagella, and as the name of a taxon. The groups included in that taxon have however varied widely, creating the 'heterokont problem', now resolved by the definition of the stramenopiles.

History

The term 'stramenopile' was introduced by D. J. Patterson in 1989, defining a group that overlapped with the ambiguously defined heterokonts.[12][13] The name "stramenopile" has been discussed by J. C. David.[14]

The heterokont problem

The term 'heterokont' is used as both an adjective – indicating that a cell has two dissimilar flagella – and as the name of a taxon. The taxon 'Heterokontae' was introduced in 1899 by Alexander Luther for algae that are now considered the Xanthophyceae.[15] But the same term was used for other groupings of algae. For example, in 1956, Copeland[16] used it to include the xanthophytes (using the name Vaucheriacea), a group that included what became known as the chrysophytes, the silicoflagellates, and the hyphochytrids. Copeland also included the unrelated collar flagellates (as the choanoflagellates) in which he placed the bicosoecids. He also included the not-closely related haptophytes. The consequence of associating multiple concepts to the taxon 'heterokont' is that the meaning of 'heterokont' can only be made clear by making reference to its usage: Heterokontae sensu Luther 1899; Heterokontae sensu Copeland 1956, etc. This contextual clarification is rare, such that when the taxon name is used, it is unclear how it should be understood. The term 'Heterokont' has lost its usefulness in critical discussions about the identity, nature, character and relatedness of the group.[17] The term 'stramenopile' sought to identify a clade (monophyletic and holophyletic lineage) using the approach developed by transformed cladists of pointing to a defining innovative characteristic or apomorphy.[18]

Over time, the scope of application has changed, especially when in the 1970s ultrastructural studies revealed greater diversity among the algae with chromoplasts (chlorophylls a and c) than had previously been recognized. At the same time, a protistological perspective was replacing the 19th century one based on the division of unicellular eukaryotes into animals and plants. One consequence was that an array of heterotrophic organisms, many not previously considered as 'heterokonts', were seen as related to the 'core heterokonts' (those having anterior flagella with stiff hairs). Newly recognized relatives included the parasitic opalines, proteromonads, and actinophryid heliozoa. They joined other heterotrophic protists, such as bicosoecids, labyrinthulids, and oomycete fungi, that were included by some as heterokonts and excluded by others. Rather than continue to use a name whose meaning had changed over time and was hence ambiguous, the name 'stramenopile' was introduced to refer to the clade of protists that had tripartite stiff (usually flagellar) hairs and all their descendants. Molecular studies confirm that the genes that code for the proteins of these hairs are exclusive to stramenopiles.[19]

Characteristics

The presumed apomorphy of tripartite flagellar hairs in stramenopiles is well characterized. The basal part of the hair is flexible and inserts into the cell membrane; the second part is dominated by a long stiff tube (the 'straw' or 'stramen'); and finally the tube is tipped by many delicate hairs called mastigonemes.[20] The proteins that code for the mastigonemes appear to be exclusive to the stramenopile clade, and are present even in taxa (such as diatoms) that no longer have such hairs.[21]

Most stramenopiles have two flagella near the apex.[22] They are usually supported by four microtubule roots in a distinctive pattern. There is a transitional helix inside the flagellum where the beating axoneme with its distinctive geometric pattern of nine peripheral couplets around two central microtubules changes into the nine-triplet structure of the basal body.[23]

Plastids

Many stramenopiles have plastids which enable them to photosynthesise, using light to make their own food. Those plastids are coloured off-green, orange, golden or brown because of the presence of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll c, and fucoxanthin. This form of plastid is called a stramenochrome or chromoplast.[a] The most significant autotrophic stramenopiles are the brown algae (wracks and many other seaweeds), and the diatoms. The latter are among the most significant primary producers in marine and freshwater ecosystems.[24] Most molecular analyses suggest that the most basal stramenopiles lacked plastids and were accordingly colourless heterotrophs, feeding on other organisms. This implies that the stramenopiles arose as heterotrophs, diversified, and then some of them acquired chromoplasts. Some lineages (such as the axodine lineage that included the chromophytic pedinellids, colourless ciliophryids, and colourless actinophryid heliozoa) have secondarily reverted to heterotrophy.[25][26]

Ecology

Some stramenopiles are significant as autotrophs and as heterotrophs in natural ecosystems; others are parasitic. Blastocystis is a gastrointestinal parasite of humans;[27] opalines and proteromonads live in the intestines of cold-blooded vertebrates and have been described as parasitic;[28] oomycetes include some significant plant pathogens such as the cause of potato blight, Phytophthora infestans.[29] Diatoms are major contributors to global carbon cycles because they are the most important autotrophs in most marine habitats.[30] The brown algae, including familiar seaweeds like wrack and kelp, are major autotrophs of the intertidal and subtidal marine habitats.[31] Some of the bacterivorous stramenopiles, such as Cafeteria, are common and widespread consumers of bacteria, and thus play a major role in recycling carbon and nutrients within microbial food webs.[32][33]

Evolution

External

Stramenopiles are most closely related to Alveolates and Rhizaria, all of which have tubular mitochondrial cristae and collectively form the SAR supergroup, whose name is formed from their initials.[34][26][35] The ancestor of the SAR supergroup appears to have captured a unicellular photosynthetic red alga, and many Stramenopiles, as well as members of other SAR groups such as the Rhizaria, still have plastids which retain the double membrane of the red alga and a double membrane surrounding it, for a total of four membranes.[36] In addition, species of Telonemia, the sister group to SAR, exhibit heterokont flagella with tripartite mastigonemes, implying a more ancient origin of stramenopile characteristics.[37]

Internal

The following cladogram summarizes the evolutionary relationships between Stramenopiles. The phylogenetic relationships of Bigyra vary greatly from one analysis to the next: it has been recovered as either monophyletic[38][39] or paraphyletic. When paraphyletic, the branching order of the bigyran groups also varies: in some studies Sagenista is the most basal-branching clade,[38][40][41] while in others Opalozoa is the most basal.[42] Nonetheless, Platysulcea is consistently recovered as the sister clade to all other stramenopiles.[39][40] In addition, a flagellate species discovered in 2023, Kaonashia insperata, remains in an uncertain phylogenetic position, but more closely related to Gyrista than to other clades.[41]

| Stramenopiles |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

The classification of the Stramenopiles according to Adl et al. (2019), with additions from newer research:[43] [4]

- Platysulcea Cavalier-Smith 2017[39]

- Bigyra Cavalier-Smith 1998, emend. 2006

- Opalozoa Cavalier Smith 1991, emend. 2006

- Nanomonadea Cavalier-Smith 2012

- Opalinata Wenyon 1926, emend. Cavalier-Smith 1997 [=Slopalinida Patterson 1985]

- Bicosoecida Grasse 1926, emend. Karpov 1998

- Sagenista Cavalier-Smith 1995

- Labyrinthulomycetes Dick 2001

- Pseudophyllomitidae Shiratori et al. 2016[40]

- Opalozoa Cavalier Smith 1991, emend. 2006

- Gyrista Cavalier-Smith 1998

- Bigyromonada Cavalier-Smith 1998

- Developea Karpov & Aleoshin 2016

- Pirsoniales Cavalier-Smith 1998, emend. 2006

- Pseudofungi Cavalier-Smith 1986

- Hyphochytriales Sparrow 1960

- Peronosporomycetes Dick 2001 [=Oomycetes Winter 1897, emend. Dick 1976]

- Actinophryidae Claus 1874, emend. Hartmann 1926

- Ochrophyta Cavalier-Smith 1986, emend. Cavalier-Smith & Chao 1996

- Chrysista Cavalier-Smith 1986

- Chrysoparadoxophyceae Wetherbee 2019[44]

- Chrysophyceae Pascher 1914

- Chloromorophyceae (nomen dubium)[45]

- Eustigmatophyceae Hibberd & Leedale 1971

- Olisthodiscophyceae Barcytė, Eikrem & M.Eliáš, 2021[46][47]

- Phaeophyceae Hansgirg 1886

- Phaeosacciophyceae R.A.Andersen, L.Graf & H.S.Yoon 2020[48]

- Phaeothamniophyceae Andersen & Bailey in Bailey et al. 1998

- Raphidophyceae Chadefaud 1950, emend. Silva 1980

- Schizocladiophyceae Henry, Okuda & Kawai, 2003

- Synchromophyceae S.Horn & C.Wilhelm 2007 [=Picophagea Cavalier-Smith 2006, emend. 2017]

- Xanthophyceae Allorge 1930, emend. Fritsch 1935 [Heterokontae Luther 1899; Heteromonadea Leedale 1983; Xanthophyta Hibberd 1990]

- Diatomista Derelle et al. 2016, emend. Cavalier-Smith 2017

- Bolidophyceae Guillou et al. 1999

- Diatomeae Dumortier 1821 [=Bacillariophyta Haeckel 1878]

- Dictyochophyceae Silva 1980

- Pelagophyceae Andersen & Saunders 1993

- Pinguiophyceae Kawachi et al. 2003

- Chrysista Cavalier-Smith 1986

- Bigyromonada Cavalier-Smith 1998

Notes

- They are not called chloroplasts, the most common form of photosynthetic plastid. If used narrowly, a chloroplast is a plastid which contains chlorophyll B, as in green algae, some euglenids, and the land plants.

References

External links

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.