শীর্ষ প্রশ্ন

সময়রেখা

চ্যাট

প্রসঙ্গ

যোগব্যায়াম

যোগশাস্ত্র উইকিপিডিয়া থেকে, বিনামূল্যে একটি বিশ্বকোষ

Remove ads

যোগ ভারতীয় উপমহাদেশে উদ্ভূত ঐতিহ্যবাহী শারীরবৃত্তীয় এবং মানসিক সাধনপ্রণালী।[১] শব্দটি দ্বারা হিন্দু, বৌদ্ধ ও জৈন ধর্মের ধ্যানপ্রণালীকেও বোঝায়।[২][৩][৪] হিন্দুধর্মে এটি হিন্দু দর্শনের ছয়টি প্রাচীনতম (আস্তিক) শাখার অন্যতম।[৫][৬] জৈনধর্মে যোগ মানসিক, বাচিক ও শারীরবৃত্তীয় কিছু প্রক্রিয়ার সমষ্টি।

হিন্দু দর্শনে যোগের প্রধান শাখাগুলি হল রাজযোগ, কর্মযোগ, জ্ঞানযোগ, ভক্তিযোগ ও হঠযোগ।[৭][৮][৯] ভারতীয় দার্শনিক সর্বপল্লী রাধাকৃষ্ণনের মতে, পতঞ্জলির যোগসূত্রে যে যোগের উল্লেখ আছে, তা হিন্দু দর্শনের ছয়টি প্রধান শাখার অন্যতম (অন্যান্য শাখাগুলি হলো কপিলের সাংখ্য, গৌতমের ন্যায়, কণাদের বৈশেষিক, জৈমিনীর পূর্ব মীমাংসা ও বদরায়ানের উত্তর মীমাংসা বা বেদান্ত)।[১০] এছাড়াও উপনিষদ্, ভগবদ্গীতা, হঠযোগ প্রদীপিকা, শিব সংহিতা ও বিভিন্ন তন্ত্রগ্রন্থে যোগ বিষয়ে আলোচনা করা হয়েছে ।

যোগ বিষয়ে উল্লিখিত পুরোনো গ্রন্থসমূহ থেকে এর সময়ক্রম সম্বন্ধে স্পষ্টধারণা পাওয়া যায় না । কিছু গ্রন্থ যেমন হিন্দুদের উপনিষদ[১১] বা বৌদ্ধধর্মের [১২] পালি ভাষায় লেখা কতিপয় ধর্মশাস্ত্রে যোগের বিষয়ে প্রথম উল্লেখ পাওয়া যায়। পতঞ্জলি যোগসূত্রসমূহ খৃস্ট জন্মের প্রায় পাঁচশ বছরের ভিতরে লেখা হয়েছিল [১৩] যদিও বিংশ শতকে এটি প্রসারতা লাভ করতে সক্ষম হয়েছিল। খৃষ্টিয় ১১ শতকে হঠযোগের পুথিসমূহের আবির্ভাব হয়েছিল তান্ত্রিক পন্থা থেকে।[১৪][১৫]

স্বামী বিবেকানন্দের সফলতার পর, উনিশ শতকের শেষভাগে এবং বিংশ শতকের প্রারম্ভ থেকে বিভিন্ন সময়ে ভারতবর্ষের যোগাচার্য্যগণ পশ্চিমা দেশসমূহে যোগবিদ্যার প্রচার করেন।[১৫] ১৯৮০ র দশকে পাশ্চাত্য দেশসমূহে এটি শরীরচর্চার অঙ্গ হিসেবে জনপ্রিয় হয়। অবশ্য ভারতীয় পরম্পরায় যোগকে কেবল এক শরীরচর্চার অঙ্গ মাত্র জ্ঞান করা হয় না, এর একটি আধ্যাত্মিক এবং ধ্যানের প্রাণতা আছে বলে বিবেচনা করা হয়।[১৬] তদুপরি, সাংখ্য দর্শনের সাথে বহু মিল থাকা যোগ হল হিন্দুধর্মের ছয়টি মূল দর্শনের একটি, যার নিজেরই এক মীমাংসা প্রণালী (epistemology) এবং তত্ত্ব (metaphysics) আছে।[১৭]

কর্কটরোগ, স্কিৎজোফ্রেনিয়া, হাঁপানি, হৃদরোগ ইত্যাদির ক্ষেত্রে যোগের সুফলতার বিষয়ে বহু পরীক্ষা নিরীক্ষা করা হয়েছে। এসব পরীক্ষাসমূহের ফলাফল এখনো স্পষ্টভাবে নির্ণয় করা সম্ভব হয়নি।[১৮][১৯] অন্যদিকে, কর্কটরোগের ক্ষেত্রে কিছু পরীক্ষার থেকে জানা গেছে যে, যোগাভ্যাস করার ফলে কর্কটরোগ হওয়ার প্রবণতা কমে যায় এবং কর্কটরোগীর মনস্তাত্ত্বিকভাবে রোগ নিরাময় করার সম্ভাবনা বৃদ্ধি পায়।

Remove ads

ব্যুৎপত্তি

সংস্কৃত "যোগ" শব্দটির একাধিক অর্থ রয়েছে।[২০] এটি সংস্কৃত "যুজ" ধাতু থেকে ব্যুৎপন্ন, যার অর্থ "নিয়ন্ত্রণ করা", "যুক্ত করা" বা "ঐক্যবদ্ধ করা"।[২১] "যোগ" শব্দটির আক্ষরিক অর্থ তাই "যুক্ত করা", "ঐক্যবদ্ধ করা", "সংযোগ" বা "পদ্ধতি"। আর "যোগযুক্ত" শব্দের অন্য একটি অর্থ হচ্ছে "একাগ্রতার সহিত"।

[২২][২৩][২৪] সম্ভবত "যুজির্সমাধৌ" শব্দটি থেকে "যোগ" শব্দটি এসেছে, যার অর্থ "চিন্তন" বা "সম্মিলন"।[২৫] দ্বৈতবাদী রাজযোগের ক্ষেত্রে এই অনুবাদটি যথাযথ। কারণ উক্ত যোগে বলা হয়েছে চিন্তনের মাধ্যমে প্রকৃতি ও পুরুষের মধ্যে ভেদজ্ঞান জন্মে।[২৬]

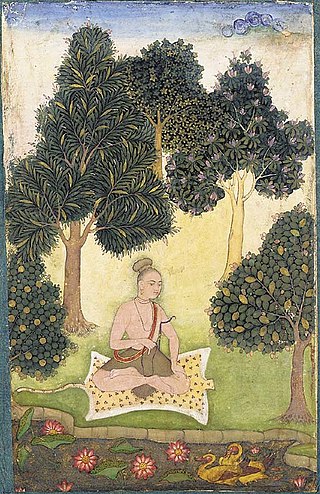

যিনি যোগ অনুশীলন করেন বা দক্ষতার সহিত উচ্চমার্গের যোগ দর্শন অনুসরণ করেন, তাকে যোগী বা যোগিনী বলা হয়।[২৭]

Remove ads

ইতিহাস

সারাংশ

প্রসঙ্গ

বৈদিক সংহিতায় তপস্বীদের উল্লেখ থাকলেও, তপস্যার (তপঃ) উল্লেখ পাওয়া যায় বৈদিক ব্রাহ্মণ গ্রন্থে (৯০০ থেকে ৫০০ খ্রিষ্টপূর্বাব্দ)।[২৮] সিন্ধু সভ্যতার (৩৩০০–১৭০০ খ্রিষ্টপূর্বাব্দ) বিভিন্ন প্রত্নস্থলে পাওয়া সিলমোহরে ধ্যানাসনে উপবিষ্ট ব্যক্তির ছবি পাওয়া গেছে। পুরাতত্ত্ববিদ গ্রেগরি পোসেলের মতে, এই ভঙ্গিমাটি "যোগের পূর্বসূরি এক ধর্মীয় আচারের রূপ"।[২৯] কোনো কোনো বিশেষজ্ঞ সিন্ধু সভ্যতায় প্রাপ্ত সিলমোহর এবং পরবর্তীকালের যোগ অনুশীলনের মধ্যে একটি সংযোগ সূত্রের কথা অনুমান করেছেন। কিন্তু এর কোনো স্পষ্ট প্রমাণ আজ পর্যন্ত পাওয়া যায় নি।[৩০]

ধ্যানের মাধ্যমে চেতনার সর্বোচ্চ স্তরে উন্নীত হওয়ার পদ্ধতি হিন্দুধর্মের শ্রামণিক ও ঔপনিষদ ধারায় বর্ণিত হয়েছে।[৩১]

প্রাক-বৌদ্ধ ব্রাহ্মণ্য গ্রন্থগুলিতে ধ্যানের উল্লেখ পাওয়া যায় না। তা সত্ত্বেও ওয়েইনি নিরাকার ধ্যানপদ্ধতিকে ব্রাহ্মণ্য ধর্ম থেকেও উৎসারিত বলে মনে করেছেন। এর প্রমাণস্বরূপ তিনি ঔপনিষদ বিশ্ববর্ণনা ও আদিযুগীয় বৌদ্ধ গ্রন্থগুলিতে বর্ণিত বুদ্ধের দুই গুরুর ধ্যানকেন্দ্রিক লক্ষ্যের শক্তিশালী সমান্তরাল ধারাটির উল্লেখ করেছেন।[৩২] তবে তিনি কম সম্ভাবনাময় বিষয়গুলিরও উল্লেখ করতে ভোলেননি।[৩৩] তার মতে, উপনিষদের বিশ্ববর্ণনায় ধ্যানপদ্ধতির একটি আভাস পাওয়া যায়। তিনি আরও বলেছেন, নাসদীয় সূক্ত এবং পরবর্তী ঋগ্বৈদিক যুগেও ধ্যানপ্রণালীর অস্তিত্বের প্রমাণ মেলে।[৩২]

বৌদ্ধ ধর্মগ্রন্থগুলিই সম্ভবত প্রথম গ্রন্থ যেগুলিতে ধ্যানের পদ্ধতি বর্ণিত হয়।[৩৪] এই সকল গ্রন্থে বুদ্ধের আবির্ভাবের পূর্বে বিদ্যমান এবং বৌদ্ধধর্মের মধ্যে উদ্ভূত – এই উভয় প্রকার ধ্যানপ্রণালীরই বর্ণনা পাওয়া যায়।[৩৫] হিন্দু সাহিত্যে "যোগ" শব্দটি প্রথম উল্লিখিত হয়েছে কঠোপনিষদে। উক্ত গ্রন্থে "যোগ" শব্দটির অর্থ ইন্দ্রিয় সংযোগ ও মানসিক প্রবৃত্তিগুলির উপর নিয়ন্ত্রণ স্থাপনের মাধ্যমে চেতনার সর্বোচ্চ স্তরে উন্নীত হওয়া।[৩৬] যোগ ধারণার বিবর্তন যে সকল গ্রন্থে বিধৃত হয়েছে, সেগুলি হল মধ্যকালীন উপনিষদসমূহ (৪০০ খ্রিষ্টপূর্বাব্দ), মহাভারত (ভগবদ্গীতা সহ, ২০০ খ্রিষ্টপূর্বাব্দ) ও পতঞ্জলির যোগসূত্র (১৫০ খ্রিষ্টপূর্বাব্দ)।

পতঞ্জলি যোগসূত্র

হিন্দু দর্শনে যোগদর্শন ছয়টি মূল দার্শনিক শাখার একটি।[৩৭][৩৮] যোগ শাখাটি সাংখ্য শাখাটির সঙ্গে ওতোপ্রতোভাবে জড়িত।[৩৯] পতঞ্জলি বর্ণিত যোগদর্শন সাংখ্য দর্শনের মনস্তত্ত্ব ও সৃষ্টি ও জ্ঞান-সংক্রান্ত দর্শন তত্ত্বকে গ্রহণ করলেও, সাংখ্য দর্শনের তুলনায় পতঞ্জলির যোগদর্শন অনেক বেশি ঈশ্বরমুখী।[৪০][৪১] অবশ্য যোগ ও সাংখ্যের সমান্তরাল ধারাদুটি পরস্পরের খুব কাছ দিয়ে প্রবাহিত হয়। ম্যাক্স মুলারের মতে, "the two philosophies were in popular parlance distinguished from each other as Samkhya with and Samkhya without a Lord...."[৪২] হেইনরিখ জিমার উভয়ের পারস্পরিক ঘনিষ্ঠ সম্বন্ধটি বর্ণনা করতে গিয়ে বলেছেন:

These two are regarded in India as twins, the two aspects of a single discipline. Sāṅkhya provides a basic theoretical exposition of human nature, enumerating and defining its elements, analyzing their manner of co-operation in a state of bondage ("bandha"), and describing their state of disentanglement or separation in release ("mokṣa"), while Yoga treats specifically of the dynamics of the process for the disentanglement, and outlines practical techniques for the gaining of release, or "isolation-integration" ("kaivalya").[৪৩]

পতঞ্জলিকে আনুষ্ঠানিক যোগ দর্শনের প্রতিষ্ঠাতা মনে করা হয়।[৪৪] পতঞ্জলি যোগ, যা মনকে নিয়ন্ত্রণ করার একটি উপায়, তাকে রাজযোগ নামে চিহ্নিত করা হয়।[৪৫] পতঞ্জলি তার দ্বিতীয় সূত্রে যোগের যে সংজ্ঞা দিয়েছেন, সেটিকেই তার সমগ্র গ্রন্থের সংজ্ঞামূলক সূত্র মনে করা হয়:

যোগঃ চিত্তবৃত্তি নিরোধঃ

- যোগসূত্র ১.২

এই সংক্ষিপ্ত সংজ্ঞাটির মধ্যে তিনটি সংস্কৃত শব্দের অর্থ নিহিত রয়েছে। আই. কে. তৈমনির অনুবাদ অনুসারে, "যোগ হল মনের ("চিত্ত") পরিবর্তন ("বৃত্তি") নিবৃত্তি ("নিরোধ")।"[৪৬] সংজ্ঞায় "নিরোধ" শব্দের ব্যবহার যোগসূত্রে বৌদ্ধ ব্যবহারিক পরিভাষার গুরুত্বপূর্ণ ভূমিকাটির নির্দেশক। এই শব্দটি থেকেই প্রমাণিত হয় যে পতঞ্জলি বৌদ্ধ ধ্যানধারণা সম্পর্কে সম্যক অবগত ছিলেন এবং তা স্বপ্রবর্তিত ব্যবস্থার অন্তর্ভুক্ত করেন।[৪৭] স্বামী বিবেকানন্দ এই সূত্রটির ইংরেজি অনুবাদ করেছেন, "Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (Citta) from taking various forms (Vrittis)."[৪৮]

পতঞ্জলির রচনা "অষ্টাঙ্গ যোগ" নামে প্রচলিত ব্যবস্থাটির মূল ভিত্তি। এই অষ্টাঙ্গ যোগের ধারণাটি পাওয়া যায় যোগসূত্রের দ্বিতীয় খণ্ডের ২৯তম সূত্রে। অষ্টাঙ্গ যোগই বর্তমানে প্রচলিত রাজযোগের প্রতিটি প্রকারভেদের মৌলিক বৈশিষ্ট্য। এই আটটি অঙ্গ হল:

- ১. যম (পাঁচটি "পরিহার")

- অহিংসা, সত্য, অস্তেয়, ব্রহ্মচর্য ও অপরিগ্রহ।

- ২. নিয়ম (পাঁচটি "ধার্মিক ক্রিয়া")

- পবিত্রতা, সন্তুষ্টি, তপস্যা, সাধ্যায় ও ঈশ্বরের নিকট আত্মসমর্পণ। 'যম' ও 'নিয়ম' এ দুয়েরই উদ্দেশ্য হল ইন্দ্রিয় ও চিত্তবৃত্তিগুলিকে দমন করা এবং এগুলিকে অন্তর্মুখী করে ঈশ্বরের সঙ্গে যুক্ত করা।

- ৩. আসন

- যোগ অভ্যাস করার জন্য যে ভঙ্গিমায় শরীরকে রাখলে শরীর স্থির থাকে অথচ কোনোরূপ কষ্টের কারণ ঘটেনা তাকে আসন বলে। সংক্ষেপে স্থির ও সুখজনকভাবে অবস্থান করার নামই আসন।

- ৪. প্রাণায়ম ("প্রাণবায়ু নিয়ন্ত্রণ")

- প্রাণস্বরূপ নিঃশ্বাস-প্রশ্বাস নিয়ন্ত্রণের মাধ্যমে জীবনশক্তিকে নিয়ন্ত্রণ। মহর্ষি নগেন্দ্রনাথ প্রাণায়ামের বিভিন্ন প্রণালীতে আশ্চর্য সিদ্ধি লাভ করেন। ভস্ত্রিকা প্রাণায়াম তিনি এমন জোরে সঙ্গে করতে পারতেন যে - মনে হতো ঝড় উঠেছে। এই বিষয়টির সশ্রদ্ধ উল্লেখ আছে পরমহংস যোগানন্দ রচিত 'যোগী কথামৃত'-তে:

[৪৯]"পতঞ্জলির* অষ্টাঙ্গ যোগের মধ্যে প্রাণায়ামের** বিভিন্ন প্রণালী তিনি খুব দক্ষতার সঙ্গে আয়ত্ত করেছেন। একবার তিনি 'ভস্ত্রিকা প্রাণায়াম' আমার সামনে এমন ভয়ঙ্কর জোরের সঙ্গে করে দেখালেন যে, মনে হল যেন ঘরের মধ্যে সত্যিসত্যিই একটা প্রবল ঝড় উঠেছে । তারপর তিনি ঝড়ের মত নিশ্বাস থামিয়ে উচ্চ সমাধিতে নিমগ্ন হয়ে গিয়ে একেবারে নিষ্পন্দ হয়ে পড়লেন । ঝড়ের পর শান্তির স্বর্গীয় জ্যোতিঃর ছটা যা তাঁর বদনে দেখা গেল, তা ভোলবার নয় ।”

- ৫. প্রত্যাহার

- বাইরের বিষয়গুলি থেকে ইন্দ্রিয়কে সরিয়ে আনা। আসন ও প্রাণায়ামের সাহায্যে শরীরকে নিশ্চল করলেও ইন্দ্রিয় ও মনের চঞ্চলতা সম্পূর্ণ দূর নাও হতে পারে। এরূপ অবস্থায় ইন্দ্রিয়গুলোকে বাহ্যবিষয় থেকে প্রতিনিবৃত্ত করে চিত্তের অনুগত করাই হল প্রত্যাহার।

- ৬. ধারণা

- কোনো একটি বিষয়ে মনকে স্থিত করা। কোনো বিশেষ বস্তুতে বা আধারে চিত্তকে নিবিষ্ট বা আবদ্ধ করে রাখাকে ধারণা বলে।

- ৭. ধ্যান

- মনকে ধ্যেয় বিষয়ে বিলীন করা। যে বিষয়ে চিত্ত নিবিষ্ট হয়, সে বিষয়ে যদি চিত্তে একাত্মতা জন্মায় তাহলে তাকে ধ্যান বলে। এই একাত্মতার অর্থ অবিরতভাবে চিন্তা করতে থাকা।

- ৮. সমাধি

- ধ্যেয়ের সঙ্গে চৈতন্যের বিলোপসাধন। ধ্যান যখন গাঢ় হয় তখন ধ্যানের বিষয়ে চিত্ত এমনভাবে নিবষ্ট হয়ে পড়ে যে, চিত্ত ধ্যানের বিষয়ে লীন হয়ে যায়। এ অবস্থায় ধ্যান রূপ প্রক্রিয়া ও ধ্যানের বিষয় উভয়ের প্রভেদ লুপ্ত হয়ে যায়। চিত্তের এই প্রকার অবস্থাকেই সমাধি বলে। এই সমাধি প্রকার - সবিকল্প এবং নির্বিকল্প। সাধকের ধ্যানের বস্তু ও নিজের মধ্যে পার্থক্যের অনুভূতি থাকলে, তাকে বলা হয় সবিকল্প সমাধি। আবার সাধক যখন ধ্যেয় বস্তুর সঙ্গে একাত্ম হয়ে যান সে অবস্থাকে বলা হয় নির্বিকল্প সমধি। তখন তাঁর মনে চিন্তার কোনো লেশমাত্র থাকে না। এই সমাধি লাভ যোগসাধনার সর্বোচ্চ স্তর, যোগীর পরম প্রাপ্তি।

এই শাখার মতে, চৈতন্যের সর্বোচ্চ অবস্থায় উঠতে পারলে বৈচিত্র্যময় জগতকে আর মায়া বলে মনে হয় না। প্রতিদিনের জগতকে সত্য মনে হয়। এই অবস্থায় ব্যক্তি আত্মজ্ঞান লাভ করে। তার আমিত্ব রহিত হয়।[৫০]

Remove ads

প্রকারভেদ

যোগ দুই ভাগে বিভক্ত। যথা:

এছাড়া আরো দুই প্রকার যোগের কথা বলা হয়েছে। এই দুই প্রকার যোগ হলো মন্ত্রযোগ এবং লয়যোগ। হঠযোগের উদ্দেশ্য হচ্ছে শরীরকে সুস্থ, সবল ও দীর্ঘায়ু করা। হঠযোগীর ধারণা কোনোরূপ শক্তিকে আয়ত্ত করতে হলেই শরীরকে নিয়ন্ত্রিত করা প্রয়োজন। সাধারণ লোক যোগ বলতে হঠযোগের ব্যায়াম বা আসনগুলোকে বুঝিয়ে থাকে। রাজযোগের উদ্দেশ্য হচ্ছে জীবাত্মাকে পরমাত্মার সঙ্গে যুক্ত করা। আর এই পরমাত্মার সঙ্গে যুক্ত হওয়াই হচ্ছে জীবের মুক্তি বা মোক্ষলাভ।

তবে হঠযোগের সঙ্গে রাজযোগের ঘনিষ্ঠ সম্বন্ধও রয়েছে। সাধনার পূর্বশর্ত হচ্ছে শরীরকে সুস্থ রাখা। "শরীরমাদ্যং খলু ধর্মসাধনম"। অর্থাৎ, 'শরীর মন সুস্থ না থাকলে জাগতিক বা পারমার্থিক কোনো কর্মই সুষ্ঠুভাবে করা সম্ভব নয়'।

তথ্যসূত্র

গ্রন্থপঞ্জি

আরও পড়ুন

বহিঃসংযোগ

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads