約翰內斯·開普勒

德國數學家,天文學家和占星家 来自维基百科,自由的百科全书

約翰內斯·開普勒(德語:Johannes Kepler,1571年12月27日—1630年11月15日),德國天文學家、數學家。開普勒是十七世紀科學革命的關鍵人物。他最為人知的成就為開普勒定律,這是爾後天文學家根據他的著作《新天文學》、《世界的和諧》、《哥白尼天文學概要》萃取而成的三條定律。這些傑作對艾薩克·牛頓影響極大,啟發牛頓後來得出牛頓萬有引力定律。

開普勒曾在奧地利格拉茨的一家神學院擔任數學教師,成為漢斯·烏爾里奇·艾根伯格親王的同事。後來,他成了天文學家第谷·布拉赫的助手,並最終成為皇帝魯道夫二世及其兩任繼任者馬蒂亞斯和費迪南二世的皇家數學家。他還曾經在奧地利林茨擔任過數學教師及華倫斯坦將軍的顧問。此外,他在光學領域做了基礎性的工作,發明了一種改進型的折光式望遠鏡(開普勒望遠鏡),並提及了同時期的伽利略利用望遠鏡得到的發現。

開普勒生活的年代,天文學與占星學沒有清楚的區分,但是天文學(文科中數學的分支)與物理學(自然哲學的分支)卻有着明顯的區分。因為宗教信仰,開普勒將宗教論點和理由寫進他的作品。因為相信上帝用智慧創造世界,人只要透過自然理性之光,也可理解上帝創造的計畫。[1]。開普勒將他的新天文學描述為「天體物理學[2]」、「到亞里士多德的《形而上學》的旅行[3]」、「亞里士多德宇宙論的補充[4]」、通過將天文學作為通用數學物理學的一部分改變古代傳統的物理宇宙學[5]。

早年

約翰內斯·開普勒於1571年12月27日,也就是當年的聖若望慶日,出生在帝國自由市魏爾德爾斯塔特(位於今德國巴登-符騰堡州,斯圖加特市中心以西30公里處),有兩位哥哥和一位姐姐。他的祖父西博爾德·開普勒(Sebald K.)曾經是魏爾德爾斯塔特的市長,但是約翰內斯·開普勒出生時,開普勒家族的家業已經開始衰落。他的父親海因里希·開普勒(Heinrich K.)為了營生,當了一名危險的僱傭兵,在約翰內斯五歲的時候就離開了家庭,據說後來死於荷蘭的「八十年戰爭」。約翰內斯的母親凱瑟琳那·古爾登曼(K. Guldenmann)是一名旅店老闆的女兒,同時是一名醫生和草藥商。約翰內斯是早產兒,孩提時體弱多病;然而,他超常的數學才能經常給他外祖父旅館內的客人留下深刻印象。[6]

開普勒在很早的年紀就接觸到並喜歡上了天文學,持續了一生。在他6歲時,他看到了1577年的大彗星,並寫道[7]他「被媽媽帶到一處高地看彗星。」9歲時,他觀察到了另外一次天文事件——1580年的月食,並記錄道[7]他記得他被「叫到門外」看月食,月亮「看起來非常紅」。然而,童年患上天花,使他的視力衰弱,雙手殘廢,因此限制了他天文觀察的能力[8]。

1589年,在經歷過文法學校、拉丁學校以及毛爾布龍修道院之後,開普勒進入了圖賓根大學的神學院,師從維塔斯·穆勒(Vitus Müller)學習哲學[9]及雅各布·黑爾布蘭德(腓力·墨蘭頓在威登堡的學生)學習神學。黑爾布蘭德同時還教了另外一名當時還是學生的邁克爾·馬斯特,直至他在1590年成為圖賓根大學校長[10]。開普勒證實了自己是傑出的數學家,並作為一名熟練的占星家給同窗占星,為自己贏得了聲譽。在1583-1631年間擔任圖賓根大學數學教授的邁克爾·馬斯特林的教導下,開普勒學習了關於行星運動的托勒密體系與哥白尼學說;在那段時間,他自己成了哥白尼的擁護者,在一次學生辯論中,他從理論和神學兩個角度捍衛太陽中心說,堅稱太陽是宇宙主要的動力來源[11]。雖然開普勒很想成為牧師,但在學業將要結束之際,他被推薦擔任格拉茨新教學校(後來成為格拉茨大學)的數學與天文學教師,並於1594年4月接受該職位,時年23歲[12]。

格拉茨(1594-1600年)

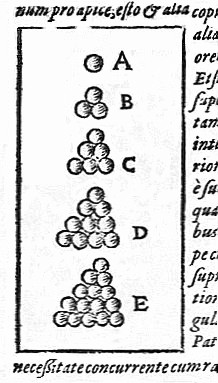

開普勒的第一部主要天文學作品——《宇宙的神秘》是第一部捍衛哥白尼學說、公開發表的作品。開普勒聲稱在格拉茨教書時的1595年7月19日頓悟,在黃道十二宮圖中展示了土星和木星定期的相遇:他意識到正多邊體按照規律的比率與一個內切圓和外接圓相連,他推測這可能是宇宙的幾何基礎。在尋找符合已知的天文學發現(甚至使用加入該系統的額外星球)、獨特排列的多面體的努力失敗後,開普勒開始用立體的多面體進行實驗。他發現五個柏拉圖立體中的每一個都可通過球體進行獨特的內切和外切;先構建這些多面體,每一個多面體裝在一個球體裡,這個球體又裝在另一個多面體內,每個多面體可產生6層,分別對應6個已知的星球——水星、金星、地球、火星、木星和土星。對這些多面體進行正確的排序——八面體、正二十面體、正十二面體、四面體和六面體,開普勒發現假設這些星球環繞着太陽,那麼球體可以按照一定的間距進行排列,間距對應於每個星球路徑的相對尺寸(在已知的天文學觀測結果的精確度範圍內)。開普勒還發現了一個公式,將每個星球的軌道大小與其軌道周期進行關聯:從內側星球到外側星球,軌道周期的增長率是軌道半徑差的兩倍。然而,開普勒後來又否定了這個公式,因為這個公式不夠精確。[13]

正如他在標題中所表明的,開普勒認為他已經揭示了上帝對宇宙的幾何規劃。開普勒對哥白尼學說的許多熱情源於對物質與精神之間的聯繫的神學信仰;宇宙本身是上帝的一個影像,太陽對應聖父,星球對應聖子,它們之間的間隔對應聖靈。《宇宙的神秘》的初稿包含了一延伸章節,用以調和太陽中心說與貌似支持地球中心說的聖經節選。[14]

在其老師邁克爾·馬斯特林的支持下,開普勒獲准在圖賓根大學理事會發表他的手稿,期間他刪掉《聖經》注釋,增加了對哥白尼學說及他的新想法更簡單易懂的描述。《宇宙的神秘》於1596年年底送印,1597年年初開普勒收到了成品,並將其贈送給著名的天文學家與贊助人。儘管該書並未被廣泛閱讀,但是它建立了開普勒作為一名高水準天文學家的聲譽;他對贊助人及格拉茨管理層充滿熱情的付出,也是得以進入贊助體系的關鍵。[15]

開普勒從未放棄柏拉圖多面體-球體宇宙學說——《宇宙的神秘》,雖然根據他後來的作品,其中的一些細節可能需要修改。他後來的主要作品,通過計算行星軌道的離心率,發現更精確的球體內外尺寸,但在某種意義上都是對該作品的進一步發展。1621年,開普勒發表了擴展後的第二版《宇宙的神秘》,比第一版長一半,腳註部分詳細記錄了在第一版發表之後25年內他所作的修正與改進。[16]

關於此書的影響,《宇宙的神秘》可以視為將尼古拉斯·哥白尼在他的作品《天體運行論》中提出的理論,進行現代化的重要第一步。當哥白尼試圖在該書中發展日心學說的時候,他用托勒密工具(即周轉圓與離心圓)解釋星球軌道速度的變化,並繼續用地球軌道中心作為參考點,而不是用太陽中心「輔助計算以便使讀者不會因偏離托勒密太多而感到混淆。」現代天文學家很大部分歸功於《宇宙的神秘》,儘管主要論點有瑕疵,「因為它代表了清除哥白尼學說中托勒密理論殘留的第一步。」[17]

1595年12月,開普勒被介紹給了芭芭拉·穆勒(B. Müller),一個帶着幼小女兒——吉瑪·德威納維爾德(Gemma van Dvijneveldt)的23歲寡婦(結過兩次婚),並開始向她求愛。穆勒不但是她前兩任丈夫財產的女繼承人,同時也是一名成功磨坊老闆的女兒。儘管開普勒繼承了他祖父的貴族身份,但是她的父親約布斯特(Jobst)最初也反對這門婚事,因為開普勒的貧困與芭芭拉不般配。開普勒完成《宇宙的神秘》之後,約布斯特動了憐憫之心,但是因為開普勒外出專注於出版的各項事宜使婚約差點告吹。然而,幫忙建立該婚配的教會官員強迫穆勒遵守他們的協議;1597年4月27日,芭芭拉和開普勒結婚。[18]

在他們婚姻的初期,他們生育了兩個子女(海因里希與蘇珊娜),但是都在襁褓時夭折了。1602年,他們又生了一個女兒(蘇珊娜),1604年,生了一個兒子(弗里德里希),1607年又生了一個兒子(路德維格)。[19]

《宇宙的神秘》出版之後,在格拉茨學校檢察員的支持下,開普勒開始了他的雄心計劃,進一步發展和完善他的作品。他計劃編寫另外4部書籍:一部關於宇宙的靜止事物(太陽和固定的星球);一部關於行星及其運動;一部關於行星的物理屬性與地理特徵的形成(側重於地球);一部是關於天空對地球的影響,涵蓋大氣光學、氣象學和占星術。[20]

他還收集許多他曾經贈送《宇宙的神秘》的天文學家們的意見,其中包括瑞瑪奴斯·烏爾蘇斯——魯道夫二世的皇家數學家,同時也是第谷·布拉赫的激烈對手。烏爾蘇斯沒有直接回復他,但是重新發表了開普勒的奉迎信,以尋求他與第谷關於第谷體系爭論(現在的叫法)中的優勢。儘管有這個污點,第谷還是開始與開普勒通信,一開始就對開普勒系統進行嚴厲但合理的批判;在許多反對的理由中,第谷對其使用哥白尼不準確的數據提出了異議。通過書信往來,第谷和開普勒就廣大範圍內的天文學問題進行了討論,並重點討論了月球現象與哥白尼學說(特別是其神學活力)。但是沒有第谷天文台更精確的數據,開普勒無法涉及其中的許多議題。[21]

後來,開普勒將精力轉向年代學與「和諧」,即音樂、數學及物質世界之間的命理關係,以及它們的占星結果。通過假設地球擁有精神(一種他後期用於解釋太陽引起行星運動的屬性),他建立了一個將占星內容和天文距離與天氣與其它地球現象聯繫起來的推測系統。然而,到了1599年,他又發現他的工作受到數據不準確性的限制——正如不斷增長的宗教緊張氣氛正威脅他在格拉茨的工作一樣。就在同年的12月份,第谷邀請開普勒在布拉格會面;1600年1月1日(甚至在他收到邀請函之前),開普勒就啟程,希望第谷的資助能夠幫解決他的哲學問題以及社會與經濟問題。[22]

布拉格(1600-1612年)

1600年2月4日,開普勒在伊澤拉河畔貝納特基(距離布拉格35km)見到了第谷·布拉赫及其助手弗朗茨·滕納格爾與朗高蒙田納斯。伊澤拉河畔貝納特基是第谷的新天文台所在地。開普勒以客人的身份在這裡住了兩個月,分析了第谷的一些火星發現;第谷嚴密地保護着他的數據,但是對開普勒的理論思想印象深刻,所以之後給了他更多接近的空間。開普勒計劃藉助火星數據測試他在《宇宙的神秘》中的理論[23],但是他預計這項工作將花費2年時間(因為第谷不允許他單純的將資料拷貝作為己用)。在約翰內斯·傑森紐斯的幫助下,開普勒嘗試與第谷協商一個更為正式的僱傭安排,但是協商在激烈的爭吵中破裂。於是開普勒在4月6日就前往布拉格。之後,開普勒和第谷很快就和解了,並最終就工資和生活安排達成了協議,6月,開普勒回到格拉茨去接他的家人。[24]

格拉茨政治上和宗教上的麻煩打碎了他立刻回到第谷天文台工作的想法;為了繼續他的天文學研究,開普勒以數學家的身份向斐迪南大公尋求了一份工作。為此,開普勒專門寫了一篇文章給斐迪南。他在文中提出了一個月球運動力學理論[25]:「地球上有一種力量,引起了月球的運動」。雖然這篇文章並未使他在費迪南宮廷獲得職位,但是卻詳細介紹了一種測量月食的新方法,他將這種方法運用到了7月10日格拉茨的月食現象。這些觀察成了他進行光學規律探索的基礎,而《天文學的光學需知》則是他光學探索的頂峰。[26]

1600年8月2日,在拒絕皈依天主教之後,開普勒和他的家人被驅逐出格拉茨。幾個月後,開普勒及他的家人來到了布拉格。差不多1601年一整年,他得到了第谷的直接資助,第谷安排他分析行星觀測結果與編寫反對第谷(此時第谷已過世)對手——烏爾蘇斯的小冊子。9月,第谷幫開普勒獲得了作為他先前向皇帝提議的新項目的合作者的委任:將取代伊拉斯謨·賴因霍爾德所作的《普魯士星表》的《魯道夫星表》。1601年10月24日第谷出人意料的逝世了,兩天之後,開普勒被委任成為他的繼任者,作為皇家數學家負責完成第谷未完成的工作。接下去作為皇家數學家的11年是開普勒一生中最為多產的時間。[27]

作為皇家數學家,開普勒的主要職責是向皇帝提供占星術方面的建議。雖然開普勒對同時代占星家對未來或特定神學事件進行準確預言的努力採取懷疑態度,但是當他還是圖賓根大學的一名學生時,他已經向他的朋友、家人和贊助人展示了極受歡迎的占星水平。除了給同盟國和外國領導人占星外,皇帝在遇到政治麻煩時,也向開普勒尋求建議。魯道夫對許多其宮廷學者(包括鍊金術士)的工作有着積極興趣,並跟蹤開普勒在物理天文學方面的工作。[28]

布拉格正式被認可的宗教教義是天主教和主穩健派,但是開普勒憑藉他在宮廷的地位可以信仰他的路德教會而不受阻礙。皇帝名義上為其家庭提供了豐厚的收入,但是皇家國庫開支過度,這意味着想要實際上獲得足夠的錢應對經濟負擔還是需要不斷的爭取。一部分源於經濟困難的原因,他和芭芭拉的家庭生活並不如意,經常為爭吵和疾病所擾。然而,宮廷生活為開普勒帶來了與其他著名學者[其中包括約翰內斯·馬修斯·瓦克·瓦克亨菲爾斯、約斯特·比爾吉、大衛·法布里奇烏斯、馬丁·巴查傑克(M. Bachazek)以及約翰內斯·布倫格(Johannes Brengger)]接觸的機會,因此他的天文學工作進展迅速。[29]

在開普勒繼續慢慢分析第谷的火星觀測數據——現在他可以擁有整體的資料——並開始了魯道夫星表的緩慢編制過程的同時,他還從其1600年關於月球的文章中拾起了對光學規律的研究。不論是月食或是日食現象都展現了無法解釋的現象,例如不可預期的陰影大小、月全食的紅色、以及傳說中環繞日全食的罕見光線。大氣折射的相關議題適用於所有天文學觀測。1603年的大部分時間,開普勒暫停了他的其它工作,而專注於光學理論研究;並由此撰寫的手稿在1604年1月1日呈給了皇帝,並以《天文學的光學需知》為題發表。文中,開普勒對控制光強的平方反比定律、平面鏡與曲面鏡的反射、針孔相機原理以及光學的天文學含義,如視差與天體的可見大小,進行了描述。他還將光學研究延伸到人的眼睛,並被神經學家廣泛認為是意識到圖像由眼睛晶狀體翻轉投射到視網膜上的第一人。這個困境的解決辦法對於開普勒來說並不是特別重要,因為他並不將其視為屬於光學的範疇,雖然他確實表明,影像由於「精神運動」在「腦穴」中得到修正[30]。今天,《天文學的光學需知》通常被認為是現代光學的基礎(雖然它明顯地沒有包含折射定律)[31]。關於投影幾何學的根源,開普勒在他作品中引入了數學實體連續變化的概念。他主張到,如果一個圓錐截面的焦點可以沿着連接焦點的線運動,那麼這個幾何形狀會把一個焦點改變或退化成另外一個。因此,當一個焦點沿着無窮大運動時,橢圓形就變成了一條拋物線,當一個橢圓的兩個焦點互相融合時,就形成了圓圈。

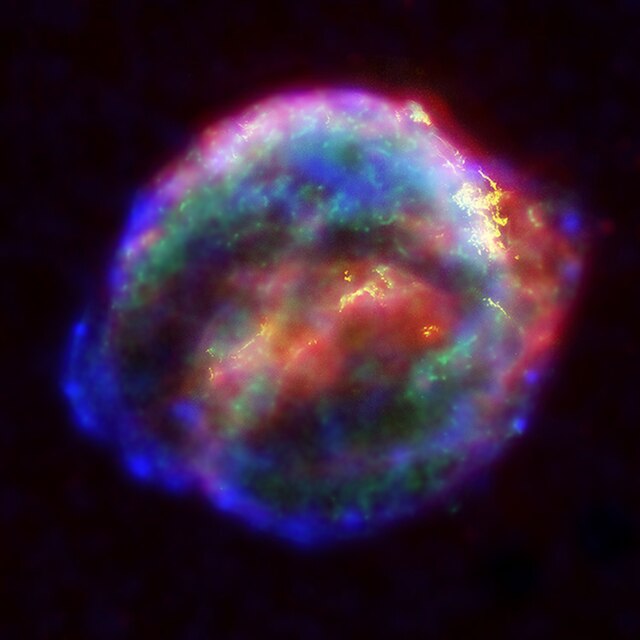

1604年10月,出現了一顆明亮的新晚星(超新星1604),但是開普勒不信謠言,直至他親眼看到了這顆晚星。他開始系統的觀察這顆新星。從星相學的角度看,1603年的結束標誌着火象三星座的開始,亦即周期800年的大交匯期的開始;占星家們將之前兩次這種時期與查理曼大帝的崛起(大約800年前)和耶穌的誕生(大約1600年前)聯繫起來,所以他們期待有重大預兆的事件出現,特別是關於皇帝。正是在這種情況下,開普勒作為皇家數學家與占星家在其兩年後《關於新星》的文中描述了這顆新星。文中,開普勒在對其他許多占星方面的解釋與流傳持懷疑態度的同時,專注於描述這顆新星的天文學屬性。他注意到了其逐漸減弱的亮度,推測它的起源,並根據視差的缺失論證它屬於固定的星體,進一步削弱了天體永恆性的教義(自亞里斯多德以後人們一直認可這樣的觀念:天體是完美與永恆的)。一顆新星的誕生意味着天體的可變性。在附錄中,開普勒還討論了波蘭歷史學家勞倫休斯·蘇斯萊格最近的年代學工作;他計算到,如果蘇斯萊格是正確的,年表提前四年,那麼伯利恆之星——類似於今日的新星——將已經正好碰到了周期800年的第一次大交匯。[32]

《新天文學》是根據第谷的方向進行的火星軌道研究(包括最初兩個關於行星運動的定律)發展的頂峰。開普勒運用等分點(哥白尼把這種數學工具排除在他的學說之外)對各種安火星軌道近似值進行重複計算,並最終創造了一個在2弧分之內(平均測量誤差)基本上與第谷的發現相一致的模型。但是他對這個複合體以及仍然有點不準確的結果感到不滿意;在某些點,這個模型與數據的差異達到8弧分。一系列傳統的數學天文學方法都使開普勒感到失望,他開始嘗試為這些數據設置一個卵形軌道。[33]

根據開普勒對宇宙的宗教觀點,太陽(父神的象徵)是太陽系的動力來源。作為物理基礎,開普勒通過類比汲取了威廉·吉爾伯特《論磁石》(1600年)中地球磁性靈魂的理論以及自己關於光學研究的工作。他假設太陽發射的動力(或動力個體)[34]隨着距離減弱,當行星靠近或遠離太陽,運動會加快或減慢[35][36]。可能這個設想的前提需要一種修復天文學秩序的數學關係。根據對地球和火星遠日點和近日點的測量,他創立了一個公式。根據這個公式,行星的運動速度與它距太陽的距離成反比。然而,想要在整個軌道周期證實這種關係,需要進行非常廣的計算;為簡化計算任務,1602年底,開普勒運用幾何學重新闡述了這個比例:行星在同樣的時間內掃過同樣的面積——開普勒關於行星運動的第二定律。[37]

之後,他運用幾何速率法則,假定軌道是蛋形軌道,開始計算火星的整體軌道。在經歷大約40次的嘗試失敗以後,1605年初,他最終偶然想到了橢圓形這個概念,他之前認為這個解決方法太簡單,以至於早期的天文學家們都忽略了[來源請求]。在發現橢圓形軌道適用於火星的數據之後,他立即推斷出所有行星都以太陽為中心按照橢圓形運動——開普勒關於行星運動的第一定律。然而,他沒有聘用計算方面的助手,所以他未將該數學分析擴展到火星之外。當年年底,他完成了《新天文學》的手稿,但是由於第谷天文台使用(第谷後人的財產)的法律爭議,直到1609年才發表。[38]

在《新天文學》完稿之後的幾年,開普勒大部分的研究都集中在《魯道夫星表》的編撰以及基於該星表的一整套星曆(對行星和星位的具體預言,但是這兩項工作在多年之後都沒完成)。他還嘗試(不成功)與意大利天文學家喬凡尼·安東尼奧·馬吉尼(Giovanni Antonio Magini)的合作。他的其它作品涉及年代學(特別是耶穌一生中事件的日期記錄)與占星學[特別是對轟動性的大災難預言的批判,比如哈利薩耶斯·羅斯林(Helisaeus Roeslin)的預言]。[39]

正當開普勒和羅斯林忙於發表一系列攻擊與回擊時,菲利普·法賽里爾斯醫生(P. Feselius)發表了一部作品,對占星學進行了全面地反駁(特別是羅斯林的作品)。一方面是出於對其所認為是占星學的多餘的回應,另一方面是出於對過度的反對聲音的回應,開普勒撰寫了《第三方調解》。表面上,這篇文章——主要是給羅斯林和法賽里爾斯的普通贊助人看的——是對爭論的學者之間的一次中立調解,但是文中體現了開普勒對占星學價值的基本觀點,文章包含了行星與個體精神之間互動的一些假設機制。開普勒認為多數傳統的占星學法則與方法是被「一隻勤勞的母雞」扒爛的「臭糞」,但是實際上認真的科學的占星家「偶爾會找到穀粒,甚至是珍珠或金塊」。[40]

1610年的頭幾個月,伽利略用他強大的新望遠鏡,發現了四顆繞着木星運動的衛星。在發表他的報告——《星夜的差使》時,伽利略諮詢了開普勒的意見,某種程度上是為了增加其觀測發現的可信度。開普勒給予了積極的回應,撰寫並發表了一篇簡短的回覆——《與星夜信使的對話》。他支持伽利略的觀測,並對伽利略的發現以及望遠鏡觀測方法對於天文學和光學以及宇宙學和占星學的含義進行了一系列的推斷。同年年底,開普勒在《四顆衛星的觀測報告》中發表了其利用望眼鏡對月球的發現,進一步支持伽利略的發現。但是令開普勒失望的是,伽利略從未發表過其對《新天文學》的(任何)反應。[41]

在聽說了伽利略用望遠鏡得到的發現之後,開普勒從科隆歐內斯特(Ernest)公爵那裡借來了一個望遠鏡,開始對望遠鏡光學進行理論和實驗研究[42]。1610年9月,作為研究成果的手稿完成,並在1611年以《折射光學》為題發表。文中,開普勒提出了雙凸會聚透鏡與雙凹發散透鏡的理論基礎——以及它們如何組合製作出一個伽利略望遠鏡——以及真實與虛擬影像、直立與倒立影像的概念和焦距對放大與縮小的影響。他還介紹了一個改進型的望遠鏡——現在稱為天文望遠鏡或開普勒望遠鏡——該望遠鏡有兩個凸透鏡,可以比伽利略的凸凹組合透鏡產生更大的放大率。[43]

1611年左右,開普勒傳閱了他的一份手稿,這份手稿最終以《夢》為題(在他過世之後)發表。這篇文章的部分目的是想描述從另外一個星球的視角來看,時下的天文學會是什麼樣子,以說明非地心學說的可行性。這份在轉手幾次後丟失了的手稿描述了一次神奇的月球之旅;它一部分是寓言,一部分是自傳,一部分是星際之旅的專著(有時候也被稱為第一部科幻作品)。多年之後,該故事的一份扭曲的版本引發了一場針對自己母親的審巫案,起因是故事講述者的母親向一名惡魔學習太空旅行的方法。隨着他母親最終被判無罪,開普勒為該故事撰寫了223個腳註——比實際的文本長7倍——對故事中隱藏的寓言性內容以及很多科學內容(尤其是關於月球地理)進行了解釋。[44]

作為那年新年的禮物,他為他的朋友也是多年的贊助人——瓦克·瓦克亨菲爾斯男爵,寫了一本簡短的小冊子,題為《新年禮物——六角雪花》。文中,他發表了他首次對雪花六角對稱性的描述,並將該問題擴展成為對稱性的一個假設性原子論物理基礎,並造就了後來人們所知道的開普勒猜想——最有效的球體填充方法說明[45][46]。開普勒是將無限小應用到數學的先驅,請參考連續性定律。

1611年,布拉格政治與宗教之間日益緊張的關係達到了白熱化的程度。魯道夫皇帝的健康狀況也在衰退,被他的弟弟馬蒂亞斯逼迫退位作為波西米亞國王。雙方都尋求開普勒占星術方面的建議,他剛好利用這個機會向他們提出和解的政治建議(跟星象無多少關係,除了勸阻激烈行動的一般陳述之外)。然而,很清楚的是開普勒在馬蒂亞斯宮廷的前景已變暗淡。[47]

就在同一年,芭芭拉感染了匈牙利斑疹熱,之後開始突然發作。當芭芭拉正在康復的時候,開普勒的三個孩子都患了天花;6歲的弗里德里希最終夭折了。之後,開普勒寫信給紐倫堡和帕多瓦的潛在贊助人。位於紐倫堡的圖賓根大學,擔心開普勒已經接觸了違反《奧格斯堡信綱》與《協同信條》的加爾文主義異端學說,因而阻止他回歸。而帕多瓦大學,在將要離職的伽利略的推薦下,希望開普勒能夠填補數學教授職位的空缺,但是開普勒不喜歡他的家庭離開德國的領土,因而他來到了奧地利的林茨,確定在這裡當一名教師和教區數學家。然而,芭芭拉病情再次復發,在開普勒回去之後不久就去世了。[48]

開普勒推遲了搬到林茨的計劃,繼續留在布拉格直到魯道夫於1612年初去世。同時遭遇了政治劇變、宗教緊張以及家庭悲劇(以及關於他妻子財產的法律糾紛),開普勒無法繼續做研究。所以他將他的書信及早期的作品拼湊成了一份編年手稿——《編年紀選集》。在馬蒂亞斯繼任神聖的羅馬皇帝之後,馬蒂亞斯重新確認了開普勒皇家數學家的職位(及薪奉)並允許他搬到林茨。[49]

林茨和其它地方(1612年-1630年)

在林茨,開普勒的主要職責(不包括完成《魯道夫星表》)是在教區學校任教並提供占星術和天文學服務。在那裡的頭些年,相比在布拉格的生活,他的經濟條件更寬鬆,宗教更自由,雖然鑑於他神學上的顧慮,路德會教堂禁止他參加聖餐。他在林茨發表的第一部作品為《德維羅紀元》(1613),該作品對耶穌誕生的年份進行了進一步的闡釋;他還參加審議,確定是否將教宗額我略十三世改革的曆法引入新教徒的德國地區;同年,他還寫了影響巨大的數學著作《求酒桶體積之新法》。該著作發表於1615年,介紹了測量容器容積的方法,如酒桶。[50]

1613年10月30日,開普勒娶了24歲的蘇珊娜·羅伊特林格(S. Reuttinger)。在其第一任妻子芭芭拉死後,開普勒在兩年間已經考慮了11個不同的對象(做決定的過程後來成了婚姻問題)[51]。他最終回過頭來選擇了羅伊特林格(第五個對象)。對她,開普勒曾寫道[52],「她用愛、謙遜的忠誠、節儉持家、勤勞及給繼子們的愛俘獲了我」。他這段婚姻的前三個孩子(格麗塔·里賈納(Margareta Regina)、凱塔琳娜與西博爾德(Sebald))在童年時代就夭折了。另外三個孩子存活下來並長大成人:克爾杜拉(Cordula,生於1621年);弗里德曼(Fridmar,生於1623年);希爾伯特(Hildebert,生於1625年)。根據開普勒傳記的作者,開普勒這段婚姻比第一段幸福。[53]

自從完成了《新天文學》之後,開普勒就開始計劃編制天文學教科書[54]。1615年,他完成了《哥白尼天文學概要》三卷中的第一卷;第一卷(第1-3冊)在1617年印刷,第二卷(第四冊)1620年印刷,第三卷(第5-7冊)在1621年印刷。儘管這個書名簡單涉及了太陽中心說,開普勒的這套教科書成了他自己橢圓定律的巔峰之作,是其最富影響力的作品。它包含了全部三條行星運動定律,並嘗試用物理因素解釋天體運動[55]。雖然它明確的將行星運動的頭兩條定律(在《新天文學》中適用於火星)擴展到其它行星、月球及木星的美第奇衛星[56],但是它並沒有解釋橢圓軌道如何從觀測資料中獲取[57]。

作為《魯道夫星表》與相關的星曆的副產品,開普勒發表了天文曆法,這套曆法非常受歡迎,並抵消了他創作其它作品的費用,特別是當皇家國庫的資助被中止後。根據他的曆法,1617年-1624年間的6年中,開普勒預測了行星位置和天氣以及政治事件;後者經常非常準確,得益於他敏銳的掌握了那個時期政治與神學的緊張關係。然而到1624年,緊張關係的升級以及預言的不準確意味着給開普勒自身帶來的政治麻煩;他最後的曆法在格拉茨被公開燒毀。[58]

1615年,一個與開普勒的弟弟克利斯朵夫(Christoph)產生經濟糾紛、名叫厄休拉·萊因戈爾德(Ursula Reingold)的女子,聲稱開普勒的母親卡塔琳娜用一種邪惡的飲料致使她生病。之後,爭吵升級,1617年,卡塔琳娜被控施行巫術;審巫案在該時期的中歐非常普遍。從1620年8月開始,她被囚禁了14個月。1621年10月,她被釋放,一部分原因是開普勒所進行的廣泛的法律辯護。原告沒有證據,只有謠言。卡塔琳娜遭受了言語恫嚇(形象描述等待她的、施予女巫的折磨),以最終逼迫她認罪。在這次審判期間,開普勒推遲了他的其它工作,轉而專注於他的「和諧理論」,並在1619年發表了他的成果——《世界的和諧》。[59]

開普勒深信「幾何事物向造物主提供了裝飾整個世界的模型」[60]。在《世界的和諧》中,他嘗試用音樂解釋自然世界的比例,特別是天文學與占星學方面[61]。「和諧」的中心是「天體音樂」,而畢達哥拉斯、托勒密以及開普勒之前的許多人都對「天體音樂」進行過研究;實際上,在《世界的和諧》剛發表之後,開普勒就捲入了與羅伯特·弗勒德(R. Fludd)的先後順序糾紛,因為後者最近剛發表了他的和諧理論。[62]

開普勒從研究正多邊形和多面體開始,包括後來被人們所熟知的開普勒多面體。從那裡,他把他的和諧分析擴展到音樂、氣象學和占星學;和諧產生於天體靈魂所作的音調,對於占星學來說,和諧源於這些音調與人類靈魂的互動。在這部作品的最後部分(第5冊),開普勒介紹了行星運動,特別是軌道速度與距太陽的軌道距離之間的關係。其它天文學家也使用了類似的關係,但是開普勒利用第谷的資料和他自己的天文學理論,更加準確的處理這些關係,並賦予了他們新的物理學意義。[63]

在許多其它和諧中,開普勒清楚的說明了人們所知的行星運動第三定律。之後,他嘗試了許多組合,直到發現(近似地)「周期的平方與平均距離的平方成正比」。雖然他給出了這次發現的日期(1618年3月8日),但是並未詳細描述他是如何得出這個結論的[64]。然而,直到17世紀60年代,人們才意識到該純力學定律對於行星動力學的更廣泛的意義。當該法則與克里斯蒂安·惠更斯剛發現的離心力定律結合時,它就能使艾薩克·牛頓、愛德蒙·哈雷、甚至克里斯多佛·雷恩(C. Wren)和羅伯特·虎克獨立的論證太陽與其行星之間假定的萬有引力隨着它們之間的距離的平方的減少而減少[65]。這就否定了學術物理學傳統的假設——不論在什麼時間,萬有引力不隨兩個天體之間的距離改變而改變,正如開普勒所做的假設以及伽利略錯誤的普遍規律,即自由落體運動加速度是一樣的,以及如伽利略的學生——波蕾莉(Borrelli)在其1666年的天體力學中所描述的一樣[66]。威廉·吉爾伯特在用磁鐵做實驗之後,確定地球的中心是一塊巨大的磁鐵。他的理論引導開普勒認為太陽的磁力驅動行星在它們自己的軌道運動。這是對行星運動的一個有趣的解釋,但是對開普勒來說,很不幸,這種解釋是錯的。在找到正確的答案之前,科學家們需要對運動有更多的了解。

1623年,開普勒最終完成了《魯道夫星表》,這在當時被認為是他主要的工作。然而,由於皇帝的出版要求以及與第谷後人之間的協商,該星表直到1627年才開始印刷。同時,宗教緊張——正在發生的「三十年戰爭」的根源——再一次使開普勒及他的家人陷入危險的境地。1625年,天主教反改革派的代理人將開普勒大部分的藏書查封,1626年,林茨城被包圍。開普勒搬到烏爾姆,在那裡他自費印刷了該星表。[67]

1628年,隨着皇帝費迪南德的軍隊在華倫斯坦將軍的指揮下獲得軍事上的勝利,開普勒成為華倫斯坦的官方顧問。雖然本質上不是將軍府的占星家,但是開普勒為華倫斯坦的占星家們提供天文學計算,並偶爾為華倫斯坦本人撰寫天宮圖。在他生命的最後幾年,開普勒花了很多時間旅行,從布拉格皇宮到林茨,從烏爾姆到扎甘臨時的家,以及最後到雷根斯堡。到雷根斯堡不久以後,開普勒就患病了。他於1630年11月15日去世,並安葬在那裡;它安葬的地點在瑞典軍隊毀壞墓地之後不再存在[68]。只有開普勒自創的墓志銘還流傳下來:

- Mensus eram coelos, nunc terrae metior umbras

- Mens coelestis erat, corporis umbra iacet.

- 「我曾測天高,今欲量地深。」

- 「我的靈魂來自上天,凡俗肉體歸於此地。」[69]

對開普勒天文學的認可

開普勒的定律並沒有立即得到認可。幾個重要人物如伽利略和勒內·笛卡爾完全忽視了開普勒的《新天文學》。許多天文學家,包括開普勒的老師——邁克爾·馬斯特林,反對開普勒將物理學引入天文學。一些人採取了折中立場。關於橢圓的虛焦點,伊斯梅爾·布羅(Ismael Boulliau)認可橢圓軌道但是用均勻運動代替開普勒的面積定律,而塞斯·沃德(Seth W.)則使用等徑運動的橢圓軌道。[70][71][72]

幾位天文學者對開普勒的理論進行了試驗,對其的各種修改違背了天文觀測的結果。在這兩顆行星沒法正常觀測到的情況下,金星與水星的兩次凌日為開普勒的理論做了靈敏的試驗。1631年的水星凌日,開普勒極其不確定水星的參數,建議觀測者在預測日期的前一天與後一天尋找凌日現象。皮埃爾·伽桑狄在預測的日期觀察到了凌日現象,證實了開普勒的預測[73]。這是首次觀測到水星凌日。然而,他試圖在一個月以後觀測金星凌日,卻因為《魯道夫星表》的誤差而失敗。伽桑狄並未意識到那次的凌日現象並非在歐洲的大部分地方都可以觀測得到,包括巴黎[74]。傑雷米亞·霍羅克斯在1639年觀測到了金星凌日。在這之前,他用自己的觀測結果修改了開普勒模型的參數,並預測了這次凌日現象,然後製作了觀測工具。他一直是開普勒模型的堅定支持者[75][76][77]。

全歐洲的天文學者們都閱讀了《哥白尼天文學概要》。開普勒死後,該書成為傳播其思想的主要工具。1630-1650年間,該書成為使用最多的天文學教科書,使許多人改信橢圓為基礎的天文學[55]。然而,很少人接受他建立於物理基礎上的天體運動的觀點。在17世紀後期,許多從開普勒的著作產生出來的物理天體學理論——尤其是喬瓦尼·阿方索·博雷利和羅伯特·虎克的理論——開始包含引力(雖然不是開普勒假定的准精神運動類)和笛卡爾慣性概念。而牛頓的《自然哲學的數學原理》則是這些理論的頂峰,在該著作中,牛頓從以力為基礎的萬有引力定律得出了開普勒行星運動定律[78]。

歷史和文化遺產

開普勒在哲學和科學編史學方面的作用超出了其在天文學與自然哲學的歷史發展中的作用。開普勒及其天體運動定律對早期的天文學史非常重要,比如孟都克拉1758年的《數學歷史》以及德朗布爾1821年的《現代天文學歷史》。這些和其它從啟蒙運動的視角編寫的歷史以懷疑和反對的態度看待開普勒的形而上學和宗教主張,但是到了後來的浪漫時期,自然哲學家們將這些元素視為他成功的關鍵。威廉姆·維赫維爾在他有着重要影響力的作品《歸納法科學的歷史》(1837年)中,發現開普勒是歸納法科學天才的原型;在他的作品《哲學與歸納科學》(1840年)中,維赫維爾將開普勒稱為科學方法最高級形式的體現。類似地,在凱瑟琳皇后購買了開普勒手稿之後第一個對其進行廣泛研究的人——恩斯特·弗里德里希·阿貝爾特(Ernst F. Apelt)認定開普勒是「科學革命」的鑰匙。阿貝爾特看過開普勒的關於數學、美感、物理學以及作為整個思想體系一部分的神學的觀點,對開普勒的生活與工作首次進行了廣泛的研究。[79]

19世紀末20世紀初,開普勒書籍出現了大量的現代翻譯版本,而他的全集的系統出版則在1937年才開始(21世紀初才接近完成),麥克斯·凱斯帕(M. Caspar)撰寫的開普勒自傳於1948年出版[80]。然而,繼阿貝爾特之後,亞歷山大·夸黑所寫的關於開普勒的作品是對開普勒宇宙學及其影響進行歷史解釋的里程碑。20世紀30-40年代,夸黑以及第一代專業科學史學工作者中的其他許多人將「科學革命」描述為科學歷史的核心事件,而開普勒是這場革命的核心人物之一。夸黑將開普勒的理論工作而不是實驗工作置於從古代到現代世界觀的知識轉變過程的中心位置。自從20世紀60年代以後,對於開普勒的歷史學術研究得到很大發展,涉及他的占星學與氣象學、幾何方法、他的宗教觀在他工作中的作用、他的文學及修辭手法、他與同時期更廣闊的文化與哲學思潮的互動,甚至是他作為一名科學歷史學家的作用[81]。

對於開普勒在「科學革命」中的地位的爭論也產生了一系列哲學和大眾的作品。其中阿瑟·庫斯勒所作的《夢遊者》(1959)是最具影響力的作品之一。在該作品中,開普勒無疑是這場革命的英雄(不管是道德上、神學上或認知上)[82]。科學哲學家,如查爾斯·桑德斯·皮爾士、諾伍德·拉塞爾·漢森(Norwood R. Hanson)、史蒂芬·托爾明與卡爾·波普爾都重複的求助於開普勒:不可比性實例、類比推理、證偽性與許多其它的哲學概念都在開普勒的作品中出現過。物理學家沃爾夫岡·泡利甚至使用開普勒與羅伯特·弗勒德的先後之爭來探究分析心理學對科學研究的意義[83]。約翰·博納維爾(J. Banville)所作的非常受歡迎的甚至是玄幻的歷史小說《開普勒》(1981),對凱斯特勒(Koestler)的敘事性非小說與科學哲學中的許多主題進行了探究[84]。更為玄幻的是最近的一部非小說類作品——《天國的密謀》(2004),該書聲稱開普勒謀殺了第谷以獲取他的數據[85]。開普勒獲得了作為科學現代性的象徵與超出時代的人物的大眾形象;科普作家卡爾·薩根稱他為「第一個天體物理學家與最後一個科學占星家」[86]。

德國作曲家保羅·欣德米特寫了一部關於開普勒的歌劇——《世界的和諧》,以及一首源於該歌劇音樂的同名交響樂。

在奧地利,開普勒留下的歷史遺產使他成為一枚銀質收藏幣的圖案之一:2002年9月10日的10歐元約翰內斯·開普勒銀質硬幣。該硬幣的反面是開普勒的畫像,他曾經在格拉茨及附近地區教學。開普勒私下與漢斯·烏爾里奇·艾根伯格親王(Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg)熟識,他很可能對艾根伯格城堡的建造產生了影響(這枚硬幣正面的圖案)。硬幣上,在他的前面鑲嵌了一個《宇宙的神秘》中的球體與多面體模型。[87]

2009年美國國家航空和宇宙航行局將開普勒對天文學領域的貢獻命名為「開普勒使命」。[88]

在新西蘭的峽灣國家森林公園,也有一座群山以開普勒命名,稱為「開普勒山」,以及一條穿過該群山的被稱為「開普勒小道」的「三日步行道」。

聖公會(美國)禮儀歷的5月23日是紀念開普勒與哥白尼的節日。[89]

天文學著作

- 《宇宙的奧秘》(Mysterium cosmographicum,1596)

- 《關於占星術更堅實的基礎》(De Fundamentis Astrologiae Certioribus,On Firmer Fundaments of Astrology (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館); 1601年)

- 《天文學的光學部分》(Astronomiae Pars Optica,1604)

- 《蛇夫座腳部的新星》(De Stella Nova in Pede Serpentarii,1604)

- 《新天文學》(Astronomia nova,1609)

- 《第三方調解》(Tertius Interveniens,1610年)

- 《與星夜信使的對話》(Dissertatio cum Nuncio Sidereo,1610年)

- 《折射光學》(Dioptrice,1611)

- 《六角的雪花》(De nive sexangula,1611年)

- 《這些年裡,聖母瑪利亞與永恆的耶穌基督展現了人類出生前的本性》(De vero Anno, quo aeternus Dei Filius humanam naturam in Utero benedictae Virginis Mariae assumpsit,1614)[90]

- 《編年紀選集》(Eclogae Chronicae,1615年,和《與星夜信使的對話》一起發表)

- 《求酒桶體積之新法》(Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum,1615年)

- 《哥白尼天文學概要》(Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae,從1618-1621年分三部分發表)

- 《世界的和諧》(Harmonices Mundi,1618)

- 《宇宙的神聖秘密》(第二版,Mysterium cosmographicum,1621年)

- 《魯道夫星表》(Tabulae Rudolphinae,1627)

- 《月亮之夢》(Somnium,1634年)

參見

引用和注釋

參考資料

外部連結

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.