I

From Wiktionary, the free dictionary

Remove ads

Такође погледајте: Додатак:Варијанте од "i"

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

Translingual

Alternative forms

Letter

I (lower case i)

- The ninth letter of the basic modern Latin alphabet.

I (lower case ı)

See also

- (Латински текст): Aa Bb Cc Dd Ee Ff Gg Hh Ii Jj Kk Ll Mm Nn Oo Pp Qq Rr Sſs Tt Uu Vv Ww Xx Yy Zz

- (Variations of letter I): Íí Ìì Ĭĭ Îî Ǐǐ Ïï Ḯḯ Ĩĩ Įį Īī Ỉỉ Ȉȉ Ȋȋ Ịị Ḭḭ Ɨɨɨ̆ ᵻ ᶖ İi Iı ɪ Ii fi ffi IJij IJij

- (Letters using dot sign): Ȧȧ Ạạ Ặặ Ậậ Ǡǡ Ḃḃ Ḅḅ Ċċ Ḋḋ Ḍḍ Ėė Ẹẹ Ḟḟ Ġġ Ḣḣ Ḥḥ Ii İi Iı Ịị Ḳḳ Ḷḷ Ṁṁ Ṃṃ Ṅṅ Ṇṇ Ȯȯ Ọọ Ợợ Ṗṗ Ṙṙ Ṛṛ Ṡṡ Ṣṣ ẛ Ṫṫ Ṭṭ Ụụ Ựự Ṿṿ Ẇẇ Ẉẉ Ẋẋ Ẏẏ Ỵỵ Żż Ẓẓ

Symbol

I

- (chemistry) Symbol for iodine.

- (physics) Isotopic spin.

- (license plate codes) Italy

- (physics, electronics) Electrical current.

- (physics, kinematics) moment of inertia.

- (biochemistry) IUPAC 1-letter abbreviation for isoleucine

- (mathematics, linear algebra) identity matrix

- (mathematical analysis, topology) the (closed) unit interval; [0, 1]

- (inorganic chemistry) Specifying an oxidation state of 1

- (music) major tonic triad

Numeral

I (upper case Roman numeral, lower case i)

See also

- Next: II (2)

Gallery

- Letter styles

- Normal and italic I

- Uppercase and lowercase I in Fraktur

See also

Other representations of I:

References

- 「I」 in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition, Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 2000, →ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

- 「I」 in Dictionary.com Unabridged, Dictionary.com, LLC, 1995–present.

Remove ads

English

Pronunciation

- (Received Pronunciation, General American) МФА(кључ): /aɪ/

- (Southern American English) МФА(кључ): /aː/

- (General Australian, New Zealand) МФА(кључ): /ɑe/

Audio (US): (file) - Риме: -aɪ

- Homophones: eye, aye, ay

Etymology 1

From Средњи Енглески I (also ik, ich), from Стари Енглески ih (also ic, iċċ (「I」)), from Пра-Германски *ik, *ek (「I」), from Proto-Indo-European *éǵh₂ (「I」). Cognate with Шкотски I, ik, A (「I」), Saterland Frisian iek (「I」), West Frisian ik (「I」), Холандски ik (「I」), Low German ik (「I」), Немачки ich (「I」), Bavarian i (「I」), Дански and Norwegian Bokmål jeg (「I」), Norwegian Nynorsk eg (「I」), Шведски jag (「I」), Icelandic ég, eg (「I」), Латински ego (「I」), Антички Грчки ἐγώ (egṓ, 「I」), Руски я (ja, 「I」), Lithuanian aš (「I」), Јерменски ես (es, 「I」). See also Енглески ich.

Pronoun

I (first person singular subject personal pronoun, objective me, possessive my, possessive pronoun mine, reflexive myself)

- The speaker or writer, referred to as the grammatical subject, of a sentence.

- 1590, Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, III.ii:

- It ill beseemes a knight of gentle sort, / Such as ye haue him boasted, to beguile / A simple mayd, and worke so haynous tort, / In shame of knighthood, as I largely can report.

- 1854, Gustave Chouquet, Easy Conversations in French, page 9:

- Here I am, sir.

Audio: (file)

- 2016, VOA Learning English (public domain)

- I know I have a pen, though…

Audio (US): (file)

- I know I have a pen, though…

- 1590, Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, III.ii:

- (nonstandard, hypercorrection) The speaker or writer, referred to as the grammatical object, of a sentence.

- Mom drove my sister and I to school.

Usage notes

- The word I is always capitalised in written English. Other forms of the pronoun, such as me and my, follow regular English capitalisation rules.

- I is the subject (nominative) form, as opposed to me, which is the objective (accusative and dative) form. Me is also used emphatically, like French moi. In some cases there are differing views about which is preferred. For example, the traditional rule followed by some speakers is to use I as the complement of the copula (It is I), but it is now more usual to choose me in this context (It's me).

- When used in lists, it is often thought more polite to refer to self last. Thus it is more natural to say John and I than I and John. In such lists, we generally use the same case form which we would choose if there were only one pronoun; since we say I am happy, we say John and I are happy, but we say Jenny saw me, so we say Jenny saw John and me. However, colloquially one might hear John and me are happy, which is traditionally seen as a case error. As a hypercorrected reaction to this, one can occasionally hear phrases like Jenny saw John and I.

Synonyms

Derived terms

- lyrical I

Translations

See I/translations § Pronoun.

See also

Енглеске личне заменице

Noun

I (uncountable)

- (metaphysics) The ego.

Derived terms

- I-hood

- I-ness

- I-ship

Etymology 2

- Стари Француски i, from Латински ī, from Etruscan I (i).

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i, plural Is or I's)

See also

Number

I (upper case, lower case i)

Etymology 3

Abbreviation.

Noun

I (countable and uncountable, plural Is)

- (US, roadway) Interstate.

- (grammar) Скраћеница од instrumental case.

Etymology 4

Interjection

I

- Obsolete spelling of aye.

References

- 「I」 in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition, Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 2000, →ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

- 「I」 in Dictionary.com Unabridged, Dictionary.com, LLC, 1995–present.

- "I" in WordNet 2.0, Princeton University, 2003.

Remove ads

Afar

Letter

I (lowercase i)

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) A a, B b, T t, S s, E e, C c, K k, X x, I i, D d, Q q, R r, F f, G g, O o, L l, M m, N n, U u, W w, H h, Y y

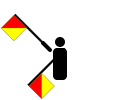

American Sign Language

Letter

(Stokoe I)

(Stokoe I)

- The letter I

Azerbaijani

Letter

I upper case (lower case ı)

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) hərf; A a, B b, C c, Ç ç, D d, E e, Ə ə, F f, G g, Ğ ğ, H h, X x, I ı, İ i, J j, K k, Q q, L l, M m, N n, O o, Ö ö, P p, R r, S s, Ş ş, T t, U u, Ü ü, V v, Y y, Z z

Danish

FWOTD – 5 November 2015

Etymology

From Old Norse ír, variant of ér, from Пра-Германски *jūz, from Proto-Indo-European *yū́.

Pronunciation

Pronoun

I (objective jer, possessive jeres)

- (personal) you, you all (second person plural)

- I må ikke gå derind!

- You can't go in there!

- 2014, Diverse forfattere, Fire uger blev til fire år - og andre beretninger, Lindhardt og Ringhof →ISBN 9788711336083

da

—Og så er der forresten lidt mere med det samme: I må love os een ting. mor og far, I må ikke efterligne os unge! — For gør I det, ja, så kommer I til at se så morsomme ud. — I må ikke prøve på at løbe fra jeres alder, for det kan I alligevel ikke., And by the way, there's something else: You must promise us one thing, mum and dad, you may not imitate us young! — For if you do, you will look so funny. — you may not try to run way from your age, for you can't do that anyway.

- 1981, Mogens Wolstrup, Vild hyben: danske forfattere skriver om jalousi

- Men det er ikke jeres skyld, siger Ditte. I er unge og kloge. I er grimme og fantastisk smukke. I har modet! I er på rette vej med jeres show. Jeg føler med jeres oprør, og måske derfor kunne jeg ikke klare mere. Jeres hud er glat, I er startet i tide.

- But it is not your fault, Ditte says. You are young and intelligent. You are ugly and amazingly beautiful. You have the courage! You are on the right path with your show. I feel with your rebellion, and perhaps for that reason, I couldn't take any more. Your skin is smooth, you started in time.

- Men det er ikke jeres skyld, siger Ditte. I er unge og kloge. I er grimme og fantastisk smukke. I har modet! I er på rette vej med jeres show. Jeg føler med jeres oprør, og måske derfor kunne jeg ikke klare mere. Jeres hud er glat, I er startet i tide.

- 2011, Per Ullidtz, Absalons Europa, BoD – Books on Demand →ISBN 9788771142396, page 229

- Og lidt senere 」I har hørt at det er sagt: øje for øje og tand for tand. Men jeg siger jer, at I må ikke sætte jer imod det onde; men dersom nogen giver dig et slag på din højre kind, da vend ham også den anden til! ...

- And a little later 」you have heard it said: an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. But I say to you, you may not resist evil; but if anyone hits you on the right cheek, turn the other towards [whoever hit you]! ...

- Og lidt senere 」I har hørt at det er sagt: øje for øje og tand for tand. Men jeg siger jer, at I må ikke sætte jer imod det onde; men dersom nogen giver dig et slag på din højre kind, da vend ham også den anden til! ...

- 1981, Mogens Wolstrup, Vild hyben: danske forfattere skriver om jalousi

See also

Шаблон:Danish personal pronouns

References

- Шаблон:R:DDO

Remove ads

Dutch

Pronunciation

Letter

I (capital, lowercase i)

- The ninth letter of the Dutch alphabet.

See also

Esperanto

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i)

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) litero; A a, B b, C c, Ĉ ĉ, D d, E e, F f, G g, Ĝ ĝ, H h, Ĥ ĥ, I i, J j, Ĵ ĵ, K k, L l, M m, N n, O o, P p, R r, S s, Ŝ ŝ, T t, U u, Ŭ ŭ, V v, Z z

Remove ads

Estonian

Letter

Шаблон:et-letter

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/et

Finnish

Letter

Шаблон:fi-letter

See also

Noun

I

- Скраћеница од improbatur.

Remove ads

German

Pronunciation

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i)

- The ninth letter of the German alphabet.

Related terms

- I longa f

Ido

Letter

I (lower case i)

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) litero; A a, B b, C c, D d, E e, F f, G g, H h, I i, J j, K k, L l, M m, N n, O o, P p, Q q, R r, S s, T t, U u, V v, W w, X x, Y y, Z z

Italian

Pronunciation

Letter

I m or f (invariable lower case, i)

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) lettera; A a (À à), B b, C c, D d, E e (É é, È è), F f, G g, H h, I i (Í í, Ì ì, Î î, J j, K k), L l, M m, N n, O o (Ó ó, Ò ò), P p, Q q, R r, S s, T t, U u (Ú ú, Ù ù), V v (W w, X x, Y y), Z z

Italian alphabet на Википедији.Википедији

Italian alphabet на Википедији.Википедији

Japanese

Romanization

I

Latvian

Etymology

Proposed in 1908 as part of the new Latvian spelling by the scientific commission headed by K. Mīlenbahs, which was accepted and began to be taught in schools in 1909. Prior to that, Latvian had been written in German Fraktur, and sporadically in Cyrillic.

Pronunciation

- Шаблон:lv-IPA

| Audio: | (file) |

Letter

Шаблон:lv-letter

See also

- Letters of the Latvian alphabet:

Malay

Pronunciation

Letter

I

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/ms

Middle English

Alternative forms

Etymology

From Стари Енглески iċ, from Пра-Германски *ek, *ik, from Proto-Indo-European *éǵh₂. More at English I.

Pronunciation

Pronoun

I (accusative me, genitive min, genitive determiner mi, min)

- I (first-person singular subject pronoun)

Descendants

References

- 「ich (pron.)」 in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007, retrieved 2018-04-05.

Norwegian Bokmål

Pronunciation

Pronoun

I

- (dialect) I: a first-person singular personal pronoun

- (rare, archaic) ye: a second-person plural nominative pronoun

Portuguese

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i)

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) letra; A a (Á á, À à, Â â, Ã ã), B b, C c (Ç ç), D d, E e (É é, Ê ê), F f, G g, H h, I i (Í í), J j, K k, L l, M m, N n, O o (Ó ó, Ô ô, Õ õ), P p, Q q, R r, S s, T t, U u (Ú ú), V v, W w, X x, Y y, Z z

Romanian

Pronunciation

- МФА(кључ): /i/

Letter

I (lowercase i)

Usage notes

- Generally represents the phoneme /i/. Preceded by H and followed by Î.

- Before vowels, this letter usually takes on the sound of /j/

- ianuarie /ja.nuˈa.ri.e/

- At the ends of words (except verb infinitives, and those ending in a consonant cluster ending in l or r), the letter palatalizes the previous syllable and is "whispered": /ʲ/

- băieți /bəˈjetsʲ/

Saanich

Pronunciation

Letter

I

See also

- (Латиница-текст слова) A, Á, Ⱥ, B, C, Ć, Ȼ, D, E, H, I, Í, J, K, Ꝁ, Ꝃ, ₭, Ḵ, Ḱ, L, Ƚ, M, N, Ṉ, O, P, Q, S, Ś, T, Ⱦ, Ṯ, Ŧ, U, W, W̲, X, X̲, Y, Z, s, ,

Scots

Etymology 1

From Стари Енглески iċ, from Пра-Германски *ek, *ik, from Proto-Indo-European *éǵh₂.

Pronoun

I (first person singular, emphatic I)

Synonyms

See also

- mei

- ma

- mine

Etymology 2

Letter

I

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/sco

Skolt Sami

Pronunciation

- (phoneme) Lua грешка in Модул:languages/doSubstitutions at line 80: Substitution data 'sms-sortkey' does not match an existing module..

Letter

Lua грешка in Модул:languages/doSubstitutions at line 80: Substitution data 'sms-sortkey' does not match an existing module..

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/sms

Slovene

Pronunciation

Letter

I (capital, lowercase i)

Somali

Pronunciation

Letter

Шаблон:so-letter

Usage notes

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/so

Spanish

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i)

- The ninth letter of the Spanish alphabet.

Adjective

I

- Скраћеница од ilustre.

- La I municipalidad de Valparaíso.

Swedish

Alternative forms

Etymology

From Old Swedish ī, īr, from Old Norse ír, variant of ér, from Пра-Германски *jīz, variant of *jūz, from Proto-Indo-European *yū́.

Pronunciation

- Риме: -iː

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i)

- The ninth letter of the Swedish alphabet.

Pronoun

I (personal pronoun)

Synonyms

Turkish

Letter

Шаблон:tr-letter

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/tr

Vietnamese

Pronunciation

Letter

Шаблон:vi-letter

See also

- Шаблон:list:Latin script letters/vi

Zulu

Letter

I (upper case, lower case i)

See also

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads