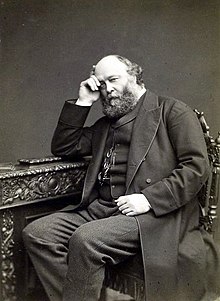

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

British politician and prime minister (1830-1903) From Wikiquote, the free quote compendium

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (3 February 1830 – 22 August 1903), styled Lord Robert Cecil before the death of his elder brother in 1865, and Viscount Cranborne from June 1865 until his father died in April 1868, was a three-time Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, during 1885–1886, 1886–1892 and 1895–1902.

Quotes

1850s

- We are not the same people that we have been, either in our social characteristics, in our patriotic sentiments, or in the tone of our moral and religious feelings.

- Speech at the Oxford Union (February 1850), quoted in H. A. Morrah, The Oxford Union, 1823-1923 (1923), p. 139

- On reflection, I am convinced that turbulence as well as every other evil temper of this evil age belongs not to the lower but to the middle classes.

- Journal entry (28 March 1852), quoted in Lady Gwedolen Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume I (1921), p. 32

- In an age when national greatness depends not on numbers or on territory, but on intelligence, the development of intelligence is a duty the neglect of which will hazard our national position. In a day when thought, not force, is the ruler of mankind, and when in domestic government numbers are more powerful than wealth, it is of the most vital importance to the stability of our institutions that that thought should be sound and those numbers enlightened.

- Address (titled "National Education") in the lecture hall of the Mechanics' Institution in Stamford (6 November 1856), quoted in The Times (11 November 1856), p. 6

- The fact was, that articles of prime necessity, such as tea and sugar, were adulterated to such an extent as materially to affect the health of an enormous portion of the population, and, the poor man being unable to protect himself, he contended that it was the duty of this House to step in and protect him.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 July 1859), during the second reading of the Bill to afford protection to the poor against being imposed on in the purchase of adulterated articles, by empowering local bodies to employ paid analysts

- A gram of experience is worth a ton of theory.

- 'Fiat Experimentum in Corpore Vili', Saturday Review (25 June 1859), p. 776

- Now if Conservative has any meaning at all, it means anti-Radical. The Radicals are the only inheritors of the revolutionary views which the Conservative party was set up to counteract; and the two can no more act together, if both are honest, than a weasel can act with a rat. Hostility to Radicalism, incessant, implacable hostility, is the essential definition of Conservatism. The fear that the Radicals may triumph is the only final cause that the Conservative party can plead for their own existence.

- 'English Politics and Parties', Bentley's Quarterly Review, vol. I (March & July 1859), p. 12

- [T]he splitting up of mankind into a multitude of infinitesimal governments, in accordance with their actual differences of dialect or their presumed differences of race, would be to undo the work of civilisation and renounce all the benefits which the slow and painful process of consolidation has procured for mankind...It is the agglomeration and not the comminution of states to which civilisation is constantly tending; it is the fusion and not the isolation of races by which the physical and moral excellence of the species is advanced. There are races, as there are trees, which cannot stand erect by themselves, and which, if their growth is not hindered by artificial constraints, are all the healthier for twining round some robuster stem.

- 'English Politics and Parties', Bentley's Quarterly Review, vol. I (March & July 1859), p. 22

- [T]hough it is England's right to enforce the law of Europe [i.e. treaties] as between contending states, she has no claim, so long as her own interests are untouched, to interfere in the national affairs of any country, whatever the extent of its misgovernment or its anarchy.

- 'English Politics and Parties', Bentley's Quarterly Review, vol. I (March & July 1859), p. 23

- Not the number of noses, but the magnitude of interests, should furnish the elements by which the proportion of representation should be computed...The classes that represent civilisation, the holders of accumulated capital and accumulated thought have a right to require securities to protect them from being overwhelmed by hordes who have neither knowledge to guide them nor stake in the Commonwealth to control them.

- 'English Politics and Parties', Bentley's Quarterly Review, vol. I (March & July 1859), pp. 28-29

- The days and weeks of screwed-up smiles and laboured courtesy, the mock geniality, the hearty shake of the filthy hand, the chuckling reply that must be made to the coarse joke, the loathsome, choking compliment that must be paid to the grimy wife and sluttish daughter, the indispensable flattery of the vilest religious prejudices, the wholesale deglutition of hypocritical pledges.

- On canvassing for election; 'The Faction-Fights', Bentley's Quarterly Review, vol. II (March & July 1859), p. 355

1860s

- And above and beyond the mere commercial gain, there rose under Mr. Gladstone's magic wand the vista of an age of security and peace—disbanded armaments, forgotten jealousies, immunity not only from the scourge but from the panic of war; pleasant dreams, constantly belied by experience, constantly renewed by theorists, but too closely linked to the hopes of all who believe either in material progress or in the promises of religion ever to be abandoned as chimera.

- 'The Budget and the Reform Bill, Quarterly Review, vol. 107 (January & April 1860), p. 516

- Wherever democracy has prevailed, the power of the State has been used in some form or other to plunder the well-to-do classes for the benefit of the poor.

- 'The Budget and the Reform Bill, Quarterly Review, vol. 107 (January & April 1860), p. 524

- It was a part of a budget which even three months had proved to be a mass of miscalculation; it was the pet scheme of a cosmopolitan school who love England little, and whom England loves less, whose sympathies are half-American and half-French; and it was the first application of a theory of combined taxation and reform, according to which the poor were exclusively to fix the revenue which the rich were exclusively to pay.

- ‘The Conservative Reaction’, Quarterly Review, vol. 108 (July & October 1860), p. 276

- The really remarkable fact which is to be inferred from the conduct of the Southern States is, the genuine alarm with which they regarded the workings of Democracy. ... They had acted in partnership with one for seventy years. They had watched it ripening year by year to the full development of mob supremacy. ... They deliberately decided that civil war, with all its horrors, and with all its peculiar risks to themselves as slaveowners, was a lighter evil than to be surrendered to the justice or the clemency of a victorious Democracy. It is not for Europe to dispute the accuracy of their judgment.

- 'Democracy on its Trial', Quarterly Review, vol. 110 (July & October 1861), p. 274

- First-rate men will not canvass mobs; and if they did, the mobs would not elect the first-rate men.

- 'Democracy on its Trial', Quarterly Review, vol. 110 (July & October 1861), p. 281

- [T]here is no more formidable obstacle than the Established Church to the spirit of rash and theoretic change which we, almost alone among the nations, have escaped .

- 'Church-rates', Quarterly Review, vol. 110 (July & October 1861), p. 545

- In the supreme struggle of social order against anarchy, we cannot deny to the champions of civilised society the moral latitude which is by common consent accorded to armed men fighting for their country against a foreign foe.

- On Lord Castlereagh's use of bribery to pass the Irish Act of Union; 'Lord Castlereagh', Quarterly Review, vol. 111 (January & April 1862), p. 204

- If any fact was clear amid the bewildering confusion of the French Revolution, it was that the gentleness, the concessions, the morbid tenderness of Louis XVI had only tended to precipitate his own and his people's doom, and aggravate the ferocity of those he tried by kindness to disarm.

- 'Stanhope's Life of Pitt', Quarterly Review, vol. 111 (January & April 1862), pp. 538-539

- The struggle for power in our day lies not between Crown and people, or between a caste of nobles and a bourgeoisie, but between the classes who have property and the classes who have none.

- 'The Confederate Struggle and Recognition', Quarterly Review, vol. 112 (July & October 1862), p. 542

- Political equality is not merely a folly—it is a chimera. It is idle to discuss whether it ought to exist; for, as a matter of fact, it never does. Whatever may be the written text of a Constitution, the multitude always will have leaders among them, and those leaders not selected by themselves. They may set up the pretence of political equality, if they will, and delude themselves with a belief of its existence. But the only consequences will be, that they will have bad leaders instead of good. Every community has natural leaders, to whom, if they are not misled by the insane passion for equality, they will instinctively defer. Always wealth, in some countries by birth, in all intellectual power and culture, mark out the men whom, in a healthy state of feeling, a community looks to undertake its government. They have the leisure for the task, and can give it the close attention and the preparatory study which it needs. Fortune enables them to do it for the most part gratuitously, so that the struggles of ambition are not defiled by the taint of sordid greed. They occupy a position of sufficient prominence among their neighbours to feel that their course is closely watched, and they belong to a class brought up apart from temptations to the meaner kinds of crime, and therefore it is no praise to them if, in such matters, their moral code stands high. But even if they be at bottom no better than others who have passed though greater vicissitudes of fortune, they have at least this inestimable advantage—that, when higher motives fail, their virtue has all the support which human respect can give. They are the aristocracy of a country in the original and best sense of the word. Whether a few of them are decorated by honorary titles or enjoy hereditary privileges, is a matter of secondary moment. The important point is, that the rulers of the country should be taken from among them, and that with them should be the political preponderance to which they have every right that superior fitness can confer. Unlimited power would be as ill-bestowed upon them as upon any other set of men. They must be checked by constitutional forms and watched by an active public opinion, lest their rightful pre-eminence should degenerate into the domination of a class. But woe to the community that deposes them altogether!

- 'The Confederate Struggle and Recognition', Quarterly Review, vol. 112 (July & October 1862), pp. 547-548

- A few years ago a delusive optimism was creeping over the minds of men. There was a tendency to push the belief in the moral victories of civilisation to an excess which now seems incredible. It was esteemed heresy to distrust anybody, or to act as if any evil still remained in human nature. At home we were exhorted to show "our confidence in our countrymen," by confiding the guidance of our policy to the ignorant, and the expenditure of our wealth to the needy. Abroad we were invited to believe that commerce had triumphed where Christianity had failed, and that exports and imports had banished war from the earth. And generally we were encouraged to congratulate ourselves that we were permanently lifted up from the mire of passion and prejudice in which our forefathers had wallowed. The last fifteen years have been one long disenchantment; and the American civil war is the culmination of the process.

- 'The Confederate Struggle and Recognition', Quarterly Review, vol. 112 (July & October 1862), pp. 562-563

- That great moral teacher, Mr. Punch, some years ago proclaimed a society which he called "The Anti-meddling-in-other-people's-business Society." Now, he sometimes wished in private that Her Majesty's Government belonged to that society. (Laughter and cheers.)

- Speech to the annual dinner of the 5th Lincolnshire Volunteer Corps in Stamford (22 October 1862), quoted in The Times (23 October 1862), p. 7

- For two hundred years these tests had been constantly and cheerfully subscribed by some six generations of clergymen. All these men, all the great lights of the Church since 1662, were by the sweeping denunciation of his hon. Friend accused without exception of having been compelled to tamper with their consciences. ... That long experience was the best answer to the statements which had been made. They might depend upon it that an experience of two hundred years was a better guide than the experience of his hon. Friends the Members for Canterbury or Plymouth. Oxford life was but three years in duration, and it was the experience of three years against that of two hundred. Two hundred years furnished a better average of the ordinary tendencies of humanity.

- Speech in the House of Commons (9 June 1863)

- [T]hat shapeless, formless, fibreless mass of platitudes which in official cant is called "unsectarian religion".

- 'Four Years of a Reforming Administration', Quarterly Review, vol. 113 (January & April 1863), p. 266

- Moderation, especially in the matter of territory, has never been characteristic of democracy. Wherever it has had free play, in the ancient world or in the modern, in the old hemisphere or the new, a thirst for empire, and a readiness for aggressive war, has always marked it.

- 'The Danish Duchies', Quarterly Review, vol. 115 (January & April 1864), p. 239

- In the real business of life no one troubles himself much about 'moral titles'. No one would dream of surrendering any practical security, for the advantages of which he is actually in possession, in deference of the a priori jurisprudence of a whole Academy of philosophers.

- 'The House of Commons', Quarterly Review, vol. 116 (July & October 1864), p. 263

- As property is in the main the chief subject-matter of legislation, so it is almost the only motive power of agitation. A violent political movement (setting aside those where religious controversy is at work) is generally only an indication that a class of those who have little see their way to getting more by means of a political convulsion.

- 'The House of Commons', Quarterly Review, vol. 116 (July & October 1864), pp. 265-266

- To give 'the suffrage' to a poor man is to give him as large a part in determining that legislation which is mainly concerned with property as the banker whose name is known on every Exchange in Europe, as the merchant whose ships are in every sea, as the landowner who owns the soil of a whole manufacturing town. An extension of the suffrage to the working classes means that upon a question of taxation, or expenditure, or upon a measure vitally affecting commerce, two day-labourers shall outvote Baron Rothschild. ... The bestowal upon any class of a voting power disproportionate to their stake in the country, must infallibly give that class a power pro tanto of using taxation as an instrument of plunder, and expenditure and legislation as a fountain of gain.

- 'The House of Commons', Quarterly Review, vol. 116 (July & October 1864), pp. 269-270

- [T]he common sense of Christendom has always prescribed for national policy principles diametrically opposed to those that are laid down in the Sermon on the Mount.

- Saturday Review, vol. 17, 1864, pp. 129–30

- The North is fighting for no sentimental cause—for no victory of a 'higher civilization'. It is fighting for a very ancient and vulgar object of war—for that which Russia has secured in Poland—that which Austria clings to in Venetia—that which Napoleon sought in Spain. It is a struggle for empire, conducted with a recklessness of human life which may have been paralleled in practice, but has never been avowed with equal cynicism. If any shame is left in the Americans, the first revision they will make in their constitution will be to repudiate formally the now exploded doctrine laid down in the Declaration of Independence, that 'Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed'.

- 'The United States as an Example', Quarterly Review, vol. 117 (January & April 1865), pp. 252-253

- Resistance is folly or heroism—a virtue or a vice—in most cases, according to the probabilities there are of its being successful. The perils of change are so great the promise of the most hopeful theories is so often deceptive, that it is frequently the wiser part to uphold the existing state of things, if it can be done, even though, in point of argument, it should be utterly indefensible.

- 'Parliamentary Reform', Quarterly Review, vol. 117 (January & April 1865), p. 550

- A Government which is strong enough to hold its own will generally command an acquiescence which with all but very speculative minds, is the equivalent of contentment.

- 'Parliamentary Reform', Quarterly Review, vol. 117 (January & April 1865), p. 550

- Conflict in free states is the law of life.

- 'The Church in her Relations to Political Parties', Quarterly Review, vol. 118 (July & October 1865), p. 198

- Opinions upon moral questions are more often the expression of strongly felt expediency than of careful ethical reasoning; and the opinions so formed by one generation become the conscientious convictions or the sacred instincts of the next.

- Saturday Review, vol. 29, 1865, p. 532

- We might as well hope for the termination of the struggle for existence by which, some philosophers tell us, the existence or the modification of the various species of organized beings upon our planet are determined. The battle for political power is merely an effort, well or ill-judged, on the part of the classes who wage it to better or to secure their own position. Unless our social activity shall have become paralyzed, and the nation shall have lost its vitality, this battle must continue to rage. In this sense the question of reform, that is to say, the question of relative class power, can never be settled.

- 'The Change of Ministry', Quarterly Review, vol. 120 (July & October 1866), p. 273

- It is said,—and men seem to think that condemnation can go no further than such a censure—that they brought us within twenty-four hours of revolution. ... But is it in truth so great an evil, when the dearest interests and the most sincere convictions are at stake, to go within twenty-four hours of revolution?

- On resistance to the Reform Act 1832; 'The Conservative Surrender', Quarterly Review, vol. 123 (July & October 1867), p. 543

- There can be no finality in politics.

- 'The Conservative Surrender', Quarterly Review, vol. 123 (July & October 1867), p. 557

- I have for so many years entertained a firm conviction that we were going to the dogs that I have got to be quite accustomed to the expectation.

- Letter to H. W. Acland (4 February 1867), quoted in Lady Gwedolen Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury, Volume I (1921), p. 211

- As long as I sit for a Conservative borough, I must continue to rank in the party and I will do what I can to promote good legislation. But I cannot look upon them as more likely to promote any cause I may have at heart than the other side. The suffrage is gone: they are lukewarm about the Church, and would no doubt give it up, as they have given up other things, for the sake of office. And beyond these two there is nothing, so far as I know, of which the Conservatives are in any special way the protectors.

- Letter to J. A. Shaw-Stewart (17 April 1867), quoted in Lady Gwendolen Cecil, Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury, Volume I (1921), p. 264

- He ventured to enter his most earnest protest against the mode in which several Members of that House were inclined to treat anything that ran out of the common ruck—and introduced them to schemes and ideas which former debates had not reached. The scheme of the hon. Gentleman was not new—he should not have thought that it was new to many Members of that House; the literature of the country had been full of it for three or four years. They all instinctively felt that it was a scheme that had no chance of success. It was not of our atmosphere—it was not in accordance with our habits; it did not belong to us. They all knew that it could not pass. Whether that was creditable to the House or not was a question into which he would not inquire; but every Member of the House the moment he saw the scheme upon the Paper saw that it belonged to the class of impracticable things.

- Speech in the House of Commons (30 May 1867) against John Stuart Mill's proposal for electing MPs by proportional representation

- The Lieutenant Governor of Bengal was to the fullest extent responsible for not having made any preparation against the famine...The doctrines of political economy had been worshipped as a sort of "fetish" by officials who, because they believed that in the long run supply and demand would square themselves, seemed to have utterly forgotten that human life was short, and that men could not subsist without food beyond a few days. They mechanically left the laws of political economy to work themselves out while hundreds of thousands of human beings were perishing from famine.

- Speech in the House of Commons (2 August 1867) on the Orissa famine of 1866

- The great evil, and it was a hard thing to say, was that English officials in India, with many very honourable exceptions, did not regard the lives of the coloured inhabitants with the same feeling of intense sympathy which they would show to those of their own race, colour, and tongue. If that was the case it was not their fault alone. Some blame must be laid upon the society in which they had been brought up, and upon the public opinion in which they had been trained. It became them to remember that from that place, more than from any other in the kingdom, proceeded that influence which formed the public opinion of the age, and more especially that kind of public opinion which governed the action of officials in every part of the Empire. If they would have our officials in distant parts of the Empire, and especially in India, regard the lives of their coloured fellow-subjects with the same sympathy and with the same zealous and quick affection with which they would regard the lives of their fellow-subjects at home, it was the Members of that House who must give the tone and set the example. That sympathy and regard must arise from the zeal and jealousy with which the House watched their conduct and the fate of our Indian fellow-subjects. Until we showed them our thorough earnestness in this matter—until we were careful to correct all abuses and display our own sense that they are as thoroughly our fellow-subjects as those in any other part of the Empire, we could not divest ourselves of all blame if we should find that officials in India did treat with something of coldness and indifference such frightful calamities as that which had so recently happened in that country.

- Speech in the House of Commons (2 August 1867) on the Orissa famine of 1866

- We have heard from the opposite Bench several very animated appeals to this House, and several constitutional lectures as to our duties. The noble Earl the late Foreign Secretary (the Earl of Clarendon) went so far, as I understood him, as to tell us that we must watch public opinion more closely, and pay greater attention to the majorities in the other House of Parliament. My Lords, it occurs to me to ask the noble Earl whether he has considered for what purpose this House exists, and whether he would be willing to go through the humiliation of being a mere echo and supple tool of the other House in order to secure for himself the luxury of mock legislation? I agree with my noble Friend the noble Earl (the Earl of Derby) below me that it were better not to be than submit to such a slavery.

- Speech in the House of Lords (26 June 1868)

- On...rare and great occasions, on which the national mind has fully declared itself, I do not doubt your Lordships would yield to the opinion of the country—otherwise the machinery of Government could not be carried on. But there is an enormous step between that and being the mere echo of the House of Commons...I have no fear of the conduct of the House of Lords in this respect. I am quite sure—whatever judgment may be passed on us, whatever predictions may be made, be your term of existence long or short—you will never consent to act except as a free, independent House of the Legislature, and that you will consider any other more timid or subservient course as at once unworthy of your traditions, unworthy of your honour, and, most of all, unworthy of the nation you serve.

- Speech in the House of Lords (26 June 1868)

- Social stability is ensured, not by the cessation of the demand for change—for the needy and the restless will never cease to cry for it—but by the fact that change in its progress must at last hurt some class of men who are strong enough to arrest it. The army of so-called reform, in every stage of its advance, necessarily converts a detachment of its force into opponents. The more rapid the advance the more formidable will the desertion become, till at last a point will be reached where the balance between the forces of conservation and destruction will be redressed, and the political equilibrium be restored.

- 'The Past and the Future of Conservative Policy', Quarterly Review, vol. 127 (July & October 1869), pp. 551-552

- It is only by the renunciation of all present hopes of office that Conservatives can save what yet remains to be saved of the institutions for which they profess to fight. To act the part of the fulcrum from which the least Radical portion of the party opposed to them can work upon their friends and leaders, is undoubtedly not an attractive future. In the changes of political life it may well end in the moderate Liberals enjoying a permanent tenure of office, propped up mainly by their support. Such a result, constituted as human nature is, would no doubt be irritating. Yet it is the only policy by which the Conservatives can now effectively serve their country.

- 'The Past and the Future of Conservative Policy', Quarterly Review, vol. 127 (July & October 1869), p. 560

- But an Ethiopian cannot change his skin—nor can I put off my "Toryism"—my deep distrust of the changes which are succeeding each other so rapidly. Numbers of men support them who are not of the spirit that bred them; but that spirit is essentially a pagan spirit, discarding the supernatural, and worshipping not God but man. It is creeping over Europe rapidly: and I can not put off the conviction that it is dissolving every cement that holds society together. I have given you enough and too much of my gloomy thoughts. They have been excited by reading in a Liberal paper "that learning is too high and sacred a thing to be sectarian". Bah!

- Letter to Henry Acland (12 November 1869), quoted in J. F. A. Mason, 'The Election of Lord Salisbury as Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1869', Oxoniensia, vol. xxix (1964–5), p. 188

1870s

- I do hope he [Bismarck] will burn down the Faubourg St. Antoine and crush out the Paris mob. Their freaks and madnesses have been a curse to Europe for the last eighty years.

- Letter to G. M. W. Sandford on the Paris Commune (26 October 1870), quoted in Paul Smith, Lord Salisbury on Politics: A Selection From His Articles in the Quarterly Review, 1860-1883 (1972), p. 105

- It is our political machinery which fails. Unrivalled as an instrument for enfeebling the arm of Government, and therefore hindering an excess of executive interference, it has prevented the oppressions into which the zeal of Continental bureaus constantly betrays them. It satisfies the most imperious want of a free people, which is to be let alone. It is not ineffective for purposes of mere destruction, especially when it is driven by the forces of sectarian animosity. But in matters where it is necessary that Government should govern and create, it lamentably breaks down. All the virtues that are attributed to it—in many respects justly—for the concerns of peace, make it helpless for the purposes of war.

- 'Political Lessons of the War', Quarterly Review, vol. 130 (January & April 1871), pp. 274-275

- The revolution of 1832 was, therefore, in its ultimate results, a democratic revolution, though its earlier form was transitional and incomplete. This form was productive of great advantages for the time: indeed, for some years it might be said, without exaggeration, that the accidental equilibrium of political forces which it had produced presented the highest ideal of internal government the world had hitherto seen. But it was not the less provisional on that account. The forces by which political organisms are destroyed were, for the time, balanced by influences which still lingered, and were, therefore, neutralised. But these were increasing, and the others were decaying, and the balance could not last for any length of time. It has now been finally upset, and we have now fully reached the phase of political transformation to which the revolution of 1832 logically led.

- 'Political Lessons of the War', Quarterly Review, vol. 130 (January & April 1871), pp. 279-280

- So long as we have government by party, the very notion of repose must be foreign to English politics. Agitation is, so to speak, endowed in this country. There is a standing machinery for producing it. There are rewards which can only be obtained by men who excite the public mind, and devise means of persuading one set of persons that they are deeply injured by another. The production of cries is encouraged by a heavy bounty. The invention and exasperation of controversies lead those who are successful in such arts to place, and honour, and power. Therefore, politicians will always select the most irritating cries, and will raise the most exasperating controversies the circumstances will permit.

- 'The Commune and the Internationale', Quarterly Review, vol. 130 (January & April 1871), p. 578

- The conflict between Socialism and existing civilisation must be a death-struggle. If the combat is once commenced, one or other of the combatants must perish. It is idle to plead that the schemes of these men are their religion. There are religions so hostile to morality, so poisonous to the life-springs of society, that they are outside the pale of human tolerance.

- 'The Commune and the Internationale', Quarterly Review, vol. 131 (July & October 1871), p. 562

- I wish that there was any chance of awakening England to the necessity or the duty of sustaining upon the Continent the position which she acquired and held in former times. Such a revival of feeling on her part would not only draw classes together in this country and purify our internal conflicts from the material element which is coming to be dominant in them; but it would prove an important guarantee for the maintenance of the present structure of Europe. ... [A]ny such revival of feeling in England is chimerical. ... The fault really lies in the change in the nature of spirit of the English nation. They do not wish, as they formerly did, for great national position, and they are glad to seclude themselves from European responsibilities by the protection which their insular position is supposed to give them. ... The great middle classes and the professional classes with whom power in this country really resides, have deliberately turned away from the ancient aims and policy of England in foreign affairs.

- Letter to Bille (18 April 1871), quoted in Marvin Swartz and Frank Herrmann, Politics of British Foreign Policy in the Era of Disraeli and Gladstone (1985), pp. 25-26

- Some persons, I know, entertain a notion that the proper way to educate a young man of 18 is to put before him all the arguments and systems of belief which ever have been or can be devised, and let him take his choice; but I am quite convinced that no such notion will ever commend itself to the general mass of parents in this country. They are well aware that thorny questions of controversy are not fit for men of unripe and unpractised minds, and that the only effect of asking them to choose impartially between all beliefs is to make them think that no belief is of much importance, and that at an age when temptations are strongest they may come to the conclusion that the moral maxims which rest on belief and belief alone are mere ancient and valueless superstitions.

- Speech in the House of Lords (8 May 1871)

- I am sure that no more certain method, not only of dechristianizing, but demoralizing the youth of the classes who send their children to the Universities could be found than subjecting them to the influence of tutors who would start with the idea that all beliefs should be submitted for free selection to the consciences and intelligences of their pupils.

- Speech in the House of Lords (8 May 1871)

- I am afraid a belief is prevalent that the advancement of morality is due to the action of Government authority. If so, we are in danger of abandoning the highest standard of morality, that of Christianity, and of seeking another in Acts of Parliament and regulations of police. Is there any country in the world in which the action of the Legislature has been able to supply the calls of the moralist and the teacher? 150 years ago the upper and middle classes of this country were as bad with regard to drunkenness as the lower classes are now. People did not then trust to legislative action, they resorted to civilization and religion. They trusted to allegiance to a principle, and in the upper and middle classes of this country at present drunkenness is not a prevailing vice. Why, then, not believe that the influences which had been so powerful with the upper and middle classes will be equally operative with the lower? I trust that in any measures your Lordships may be asked to pass, you will shrink from attempting a task which it is impossible for any Legislature to perform—namely, by the action of Government to insure morality among the people.

- Speech in the House of Lords (2 May 1872)

- So far as positive religion goes, the Tests Act...has left Oxford better off than it was before. There is more security for religious teaching than there was. The great effect of the Tests Act—or rather of that great movement of public opinion of which the Tests Act was only the outcome—has been negative. All hindrance to the teaching of infidelity has been taken away, and that is the great danger of the future. (Hear, hear.) The great danger is that there should be found inside our Universities—especially, I fear, inside Oxford—a nucleus and focus of infidel teaching and influence—(hear, hear)—not infidel in any coarse or abusive sense, but in that sense which Professor Palmer used the words "heathen virtue." I fear that the danger we have to look to is that some Colleges in Oxford may in the future play a part similar to that disastrous part which the German Universities have played in the de-Christianization of the upper and middle classes.

- Speech to the Church Congress in the Mechanics' Institute, Leeds (10 October 1872), quoted in The Times (12 October 1872), p. 7

- The whole of our conduct towards the Yankees is too disgusting to think calmly of. ... If we had recognised the South ten years ago, America would have now been nicely divided into hostile states.

- Letter (1872), quoted in Andrew Roberts, Lord Salisbury: Victorian Titan (1999), p. 50

- On Tory principles the case presents much that is painful, but no perplexity whatever. Ireland must be kept, like India, at all hazards: by persuasion if possible; if not, by force.

- 'The Position of Parties', The Quarterly Review, vol. 133 (July & October 1872), p. 572

- The two parties represent two opposite moods of the English mind, which may be trusted, unless past experience is wholly useless, to succeed each other from time to time. Neither of them, neither the love of organic changes nor the dislike of it, can be described as normal to a nation. In every nation, they have succeeded each other at varying intervals during the whole of the period which separates its birth from its decay. Each finds in the circumstances and constitution of individuals a regular support which never deserts it. Among men, the old, the phlegmatic, the sober-minded, among classes, those who have more to lose than to gain by change, furnish the natural Conservatives. The young, the envious, the restless, the dreaming, those whose condition cannot easily be made worse, will be rerum novarum cupidi. But the two camps together will not nearly include the nation: for the vast mass of every nation is unpolitical.

- 'The Position of Parties', The Quarterly Review, vol. 133 (July & October 1872), pp. 583-584

- [T]he central doctrine of Conservatism, that it is better to endure almost any political evil than to risk a breach of the historic continuity of government.

- 'The Programme of the Radicals', The Quarterly Review, vol. 135 (July & October 1873), p. 544

- One thing at least is clear—that no one believes in our good intentions. We are often told to secure ourselves by their affections, not by force. Our great-grand children may be privileged to do it, but not we.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook on British rule in India (28 May 1874), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (1965), p. 65

- [Permitting discussions in the Indian Council seems to me] an unmeaning mimicry of the forms of popular institutions where the reality is impossible. What is called public opinion in India is frequently the opinion of a clique, and presents none of the guarantees for sound judgment possessed by a public opinion which represents the combined views of a large mass of different interests and classes. I have the smallest possible belief in 'Councils' possessing any other than consultative functions.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook (12 June 1874), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (1965), p. 104

- I am afraid a mistake was made by Lord Macaulay and others in the direction they gave to educational efforts in India. Popular education would have enabled the millions to raise themselves a little out of their extreme poverty. The University education only manufactures a redundant supply of candidate for the liberal professions in a country where the demand is small, and as a by-product turns out a formidable array of seditious article-writers.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook (25 March 1875), quoted in M. N. Das, Indian National Congress versus the British, Vol I (1978), p. 24

- I believe...all the enduring institutions which human societies have attained have been reached, not of the set design and forethought of some group of statesmen, but by that unbidden and unconscious convergence of many thoughts and wills in successive generations to which, as it obeys no single guiding hand, we may give the name of "drifting".

- Minute (20 April 1875), quoted in E. D. Steele, 'Salisbury at the India Office', in Lord Blake and Hugh Cecil (eds.), Salisbury: The Man and his Policies (1987), p. 141

- As to action the matter is simple: India is held by the sword: and its rulers must in all essentials be guided by the maxims which benefit the Government of the sword.

- Letter to Sir Philip Wodehouse (4 June 1875), quoted in Michael Bentley, Lord Salisbury's World: Conservative Environments in Late-Victorian Britain (2001), pp. 233-234

- It was time to put a stop to the growing idea that England ought to pay tribute to India as a kind of apology for having conquered her: & you have done it effectively.

- Letter to Benjamin Disraeli (16 July 1875), quoted in Marvin Swartz, Politics of British Foreign Policy in the Era of Disraeli and Gladstone (1985), p. 17

- The vast multitudes of India I thoroughly believe are well contented with our rule. They have changed masters so often that there is nothing humiliating to them in having gained a new one.

- Speech to a prize-giving ceremony in Cooper's Hill (July 1875), quoted in Frederick Sanders Pulling, The Life and Speeches of the Marquis of Salisbury, K. G. (1885), p. 222

- Speaking generally, I am desirous to push forward the argument from the interests of the people more than has hitherto been done. As I have said, I consider it to be our true rule and measure of action, and our observance of it is the one justification for our presence in India.

- Letter to Lord Northbrook (25 August 1875), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (1965), p. 65

- If England is to remain supreme, she must be able to appeal to the coloured against the white, as well to the white against the coloured. It is therefore not merely as a matter of sentiment and of justice, but as a matter of safety, that we ought to try and lay the foundation of some feeling on the part of coloured races towards the crown other than the recollection of defeat and the sensation of subjection.

- Letter to the Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton (7 July 1876), quoted in S. Gopal, British Policy in India, 1858-1905 (1965), p. 115

- It is clear enough that the traditional Palmerstonian policy [of British support for Ottoman territorial integrity] is at an end.

- Letter to Disraeli (September 1876), quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, p. 85

- Diplomacy which does not rest on force is the most feeble and futile of weapons, and except for bare self-defence, we have not the force.

- Letter to Lord Lytton (8 March 1877), quoted in David Steele, Lord Salisbury: A Political Biography (2001), p. 108

- English policy is to float lazily downstream, occasionally putting out a diplomatic boat-hook to avoid collisions.

- Letter to Lord Lytton (9 March 1877), quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, p. 130

- The commonest error in politics is sticking to the carcass of dead policies.

- Letter to Lord Lytton (25 May 1877), quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, p. 145

- I would have devoted my whole efforts to securing the waterway to India – by the acquisition of Egypt or of Crete, and would in no way have discouraged the obliteration of Turkey.

- Letter to Lord Lytton (15 June 1877), quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury. Volume II, pp. 145-146

- No lesson seems to be so deeply inculcated by the experience of life as that you should never trust experts. If you believe doctors, nothing is wholesome: if you believe the theologians, nothing is innocent: if you believe the soldiers, nothing is safe. They all require their strong wine diluted by a very large admixture of insipid common sense.

- Letter to Lord Lytton (15 June 1877), quoted in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (1999) Elizabeth M. Knowles, p. 642; this has also been published without the word "insipid".

- Salisbury said two things which are more decided than any former utterances of his: that Russia at Constantinople would do us no harm: and that we ought to seize Egypt.

- Remarks to the Cabinet, as recorded in Lord Derby's diary (16 June 1877), quoted in John Vincent (ed.), The Diaries of Edward Henry Stanley, Fifteenth Earl of Derby (1994), p. 410

- Mohammedanism has the only organization and pretty nearly the only ambition hostile to us that is left in India.

- Letter to Lord Lytton (25 June 1877), quoted in David Steele, Lord Salisbury: A Political Biography (2001), p. 122 and Shih-tsung Wang, Lord Salisbury and Nationality in the East Viewing Imperialism in Its Proper Perspective (2019)

- War is righteous or unrighteous according as it is opportune or inopportune.

- Speech in the House of Lords (17 January 1878)

- [I]f our ancestors had cared for the rights of other people, the British empire would not have been made.

- Remarks to the Cabinet, as recorded in Lord Derby's diary (8 March 1878), quoted in John Vincent (ed.), The Diaries of Edward Henry Stanley, Fifteenth Earl of Derby (1994), p. 523

- Englishmen are moderate, careful to avoid unnecessary offence, slow to come to a dangerous and violent conclusion, and tenacious and resolute when the conclusion has once been arrived at.

- Speech in the House of Lords (8 April 1878)

- We are trustees for the British Empire. We have received that trust with all its strength, all its glory, all its traditions; and the one thing we have to care for is that we pass them untarnished to our successors.

- Speech in the House of Lords (8 April 1878)

- In Europe good government and other qualities may secure the sympathy of a population. In the East the first quality that secures the sympathy of a population is the possession of strength, and the moment they were convinced that strength had gone from Turkey, the power of Turkey to maintain her Empire was gone. Are your Lordships prepared to see the allegiance of the people of Asia given up to the advancing Power? If so, I ask whether there would be any chance of maintaining the loyalty of the people of India, when once they knew that the Russian power was dominant down to the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates, and that the English power was nothing compared with it? That was the real danger which we had to fear.

- Speech in the House of Lords (18 July 1878)

- You must ask yourselves, supposing 150 years ago a school had arisen similar to schools that we have heard now, who had told and who had persuaded the English Government that such things as the conquest of India, or of Canada, or Gibraltar, or Malta, or the Cape of Good Hope—that these things were unimportant, and that the one thing was to look at home at our own parochial politics? Supposing this had been said 150 years ago, do you imagine you would now be the great, the numerous, the prosperous nation that you are?

- Speech to the London and Westminster Working Men's Constitutional Association in Hatfield Park (4 August 1879), quoted in The Times (5 August 1879), p. 4

1880s

- The hurricane that has swept us away is so strange & new a phenomenon that we shall not for some time understand its real meaning. ... It seems to me to be inspired by some definite desire for change: & means business. It may disappear as rapidly as it came: or it may be the beginning of a serious war of classes. Gladstone is doing all he can to give it the latter meaning.

- Letter to Arthur Balfour after the Conservatives' defeat in the general election (10 April 1880), quoted in Salisbury–Balfour Correspondence, ed. Robin Harcourt Williams (1988), p. 40

- I hope that we shall not go too far in accepting the clôture. ... It is not our interest to grease the wheels of all legislation: on the contrary it may do all the Conservative classes of the country infinite harm.

- Letter to Arthur Balfour (15 January 1881), quoted in Salisbury–Balfour Correspondence, ed. Robin Harcourt Williams (1988), p. 58

- I am afraid that in Asia allegiance is merely the recognition of superior strength, and that the Afghans will, on the whole, ask themselves, when they are determining to whom their allegiance shall be given, which is the stronger Power—which is the Power that can protect their friends and punish their enemies—and I am afraid that they will conclude that the stronger Power is that which advances and never retreats, and not the Power which retreats and preaches all the way.

- Speech in the House of Lords (3 March 1881)

- [A]s individuals and as nations we live in states of society utterly different from each other. As a collection of individuals, we live under the highest and latest development of civilization, in which the individual is rigidly forbidden to defend himself, because society is always ready and able to defend him. As a collection of nations we live in an age of the merest Faustrecht, in which each one obtains his rights precisely in proportion to his ability, or that of his allies, to fight for them. ... In practice it is found that International Law is always on the side of strong battalions. ... It is puerile...to apply to the dealings of a nation with its neighbour's territory the morality which would be applicable to two individuals possessing adjoining property, and protected from mutual wrong by a law superior to both.

- 'Ministerial Embarrassments', Quarterly Review, vol. 151 (January & April 1881), pp. 542-544

- I earnestly hope that the House of Lords will always continue to justify your confidence; that it will conscientiously and firmly fulfil the duties for which I think it is eminently fitted, and which are to represent the permanent and enduring wishes of the nation as opposed to the casual impulses which some passing victory at the polls may in some circumstances have given to the decisions of the other House.

- Speech in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (11 October 1881), quoted in The Times (12 October 1881), p. 7

- The Afghan looks upon an Englishman in two lights—first, as a person who is an infidel, and next as a person who has money. In the first character he is anxious to kill him, in the second he is anxious to rifle him. (Cheers and laughter.)

- Speech in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (12 October 1881), quoted in The Times (13 October 1881), p. 7

- Much has been said in the present debate about conciliation and the value of conciliatory measures to Ireland...Conciliatory legislation is infinitely superior; but it depends for its efficacy on the circumstances under which it is used, and on the manner in which it is applied. Deterrent legislation, if vigorous and strong, at least deters, whatever the value of that process may be. But conciliatory legislation only conciliates where there is a full belief on the part of those with whom you are dealing that you are acting on a principle of justice, and not that you are acting on motives of fear. Where there is a suspicion or a strong belief that your conciliatory measures have been extorted from you by the violence which they are meant to put a stop to, all the value of that conciliation is taken away.

- Speech in the House of Lords (5 June 1882)

- I believe there is a great deal of Villa Toryism which requires organization.

- Letter to Sir Stafford Northcote (25 June 1882), quoted in James Cornford, 'The Transformation of Conservatism in the Late Nineteenth Century', Victorian Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1 (September 1963), p. 52

- [T]he opinions which some politicians loudly express...that the maintenance of the honour of this country and jealousy for her military fame are bygone emotions which cannot live in the face of the practical spirit of the present day. ... Now, if you wish to learn whether it is true that industry can be pursued and trade can prosper while glory is tarnished and empire is destroyed, look...on this case of Egypt. You see at once what destruction there is of capital, of industry, of all those solid material advantages which your counsellors would induce you to believe are the one thing for human beings to regard. You will see how all these advantages are dissipated and destroyed at once directly the old traditional jealousy for the honour of the country is renounced by the Government.

- Speech in Willis's Rooms (29 June 1882), quoted in The Times (30 June 1882), p. 8

- Depend upon it, firmness at the right moment is the real secret of a policy of peace. (Cheers.) There is little reason to doubt that if we had Ministers of the old English type all these terrible things would not have occurred. ... I...appeal to the names...of Lord Russell and Lord Palmerston, and you will be readily sensible of the policy which they...in difficulties not unlike this, pursued, because it recognised the danger at the right time; because there was no fear of employing force when force was necessary, and therefore they escaped the terrible disasters upon which the country now seems to be rushing.

- Speech in Willis's Rooms (29 June 1882), quoted in The Times (30 June 1882), p. 8

- It is right to be forward in the defence of the poor; no system that is not just as between rich and poor can hope to survive.

- Speech in Edinburgh (24 November 1882), quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury, Volume III, p. 65

- A party whose mission is to live entirely upon the discovery of grievances are apt to manufacture the element upon which they subsist.

- Speech in Edinburgh (24 November 1882), quoted in G. Cecil, The Life of Robert, Marquis of Salisbury, Volume III, p. 65

- In the present temper of the Irish people...the extension of the suffrage now would be merely to strengthen the element which opposes the connexion with England, and strikes for independence. ... You, the constituencies of England, must settle how this question is to be dealt with. (Cheers.) If you show firmness and resolution, if you remember the great traditions of the country to which you belong, if you resolve that no disputative formulae or Liberal superstitions shall induce you to barter away the greatness of your country, I believe that a final issue may be arrived at. But if you allow the play of parties to bring about imprudent concessions, if you allow the mere impotence of a divided English opinion to permit the establishment of an independence or a quasi independence in Ireland, the days of England's great pre-eminence among the nations of the earth are numbered. (Loud cheers.)

- Speech in Birmingham (29 March 1883), quoted in The Times (30 March 1883), p. 10

- [A] great and vital question has been raised in India. (Hear, hear.) It is...the question whether Englishmen in that part of the empire shall or shall not be placed at the mercy of native judges. ... [I]n dealing with foreign countries we have been singularly sensitive of the danger of subjecting Europeans to Oriental tribunals. In Turkey, in Egypt, on the shore of Africa, in China, in Japan, we have always pursued the same policy—to insist that an Englishman, if he has a cause to try, or if he were indicted or attacked in law by any native, should have someone of his own blood and religion...in the Court by which he was tried. ... What would your feelings be if you were in some distant and thinly-populated land, far from all English succour, and your life or honour were exposed to the decision of some tribunal consisting of a coloured man; what would your feelings of security be? (Hear, hear.) You would know that his thoughts were not your thoughts, that he could not justly estimate the circumstances or feelings in which you acted (hear, hear), and that, perhaps, his view of judicial duties was not such as Englishmen are accustomed to find in the Judges to whom their fortunes are consigned. (Cheers.)

- Speech in Birmingham (29 March 1883), quoted in The Times (30 March 1883), p. 10

- In our belief, the great empire of England, which we have inherited from our forefathers, concerns all alike, but it concerns those most who depend most for trade and employment upon the constant prosperity of the country. (Cheers.) I do not believe that England, stripped of India, stripped of its colonies, humbled before Europe, would be a happy England for the working classes. (Cheers.) We have received from the self-denial, the heroic actions of our forefathers a great empire. We mean, if we can, to keep it (cheers), to develop it, to strengthen it, to enrich it, and that not in the interests of a class, but of all, and most of all the industrial classes of this country. (Loud and prolonged cheers.)

- Speech in Birmingham (29 March 1883), quoted in The Times (30 March 1883), p. 10

- As I have said, there are two points or two characteristics of the Radical programme which it is your special duty to resist. One concerns the freedom of individuals. After all, the great characteristic of this country is that it is a free country, and by a free country I mean a country where people are allowed, so long as they do not hurt their neighbours, to do as they like. I do not mean a country where six men may make five men do exactly as they like. That is not my notion of freedom.

- Speech to the third annual banquet of the Kingston and District Working Men's Conservative Association (13 June 1883), quoted in The Times (14 June 1883), p. 7

- Half a century ago, the first feeling of all Englishmen was for England. Now, the sympathies of a powerful party are instinctively given to whatever is against England. It may be Boers or Baboos, or Russians or Affghans, or only French speculators—the treatment these all receive in their controversies with England is the same: whatever else my fail them, they can always count on the sympathies of the political party from whom during the last half century the rulers of England have been mainly chosen. .. . It is striking, though by no means a solitary indication of how low, in the present temper of English politics, our sympathy with our own countrymen has fallen. Of course, we shall be told that a conscience of exalted sensibility, which is the special attribute of the Liberal party, has enabled them to discover, what English statesmen had never discovered before, that the cause to which our countrymen are opposed is generally the just one. ... For ourselves, we are rather disposed to think that patriotism has become in some breasts so very reasonable an emotion, because it is ceasing to be an emotion at all; and that these superior scruples, to which our fathers were insensible, and which always make the balance of justice lean to the side of abandoning either our territory or our countrymen, indicate that the national impulses which used to make Englishmen cling together in face of every external trouble are beginning to disappear.

- ‘Disintegration’, Quarterly Review, vol. 156 (July & October 1883), pp. 562-563

- It is patent on the face of history that the aggregates of men who form communities, like the aggregates of atoms that form living bodies, are subject to laws of progressive change – be it towards growth or towards decay.

- 'Disintegration', Quarterly Review, vol. 156 (July & October 1883), p. 570

- [T]here are no absolute truths or principles in politics. We must never forget that there is a moral as well as a material contagion, which exists by virtue of the moral and material laws under which we live, and which forbid us to be indifferent, even as a matter of interest, to the well-being in every respect of all the classes who form part of the community. ... After all, whatever political arrangements we may adopt, whatever the political constitution of our State may be, the foundation of all its prosperity and welfare must be that the mass of the people shall be honest and manly, and shall have common sense. How are you to expect that these conditions will exist amongst people subjected to the frightful influences which the present overcrowding of our poor produce?

- Speech in the House of Lords (22 February 1884)

- I fear that the history of the past will be repeated in the future; that, just again, when it is too late, the critical resolution will be taken; some terrible news will come that the position of General Gordon is absolutely a forelorn and helpless one; and then, under the pressure of public wrath and Parliamentary Censure, some desperate resolution of sending an expedition will be formed too late to achieve the object which it is desired to gain, too late to rescue this devoted man whom we have sent forward to his fate, in time only to cast another slur upon the statesmanship of England and the resolution of the statesmen who guide England's councils.

- Speech in the House of Lords (4 April 1884)

- The terror of the Russian name has enabled them to subdue the people of Merv. The terror of the English name has disappeared since the Government retreated from Kandahar. (Cheers.) They will not learn that these tribes, these vast uncivilized multitudes, are not governed merely by the sword. They are governed by their imagination. (Hear, hear.) They are governed by their fears. They ask themselves, "Which is the Power which is strong and advancing?" and "Which is the Power which is irresolute and retreating?" They saw Russia advancing every succeeding year, they saw England giving up the advantages she had gained, and they concluded that it was for their interest to conciliate and obey Russia, and that they might safely treat England with contempt. In all these matters the Government have equally failed. (Hear, hear.) In the Transvaal and in Zululand and in Afghanistan they reversed our policy and their action is stamped with the brand of impotence, and it is impotence which they have succeeded in persuading the Asiatic is the chief characteristic of the policy of Great Britain. (Cheers.)

- Speech in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester (16 April 1884), quoted in The Times (17 April 1884), p. 6

- Constitutional institutions are splendid things, but whoever heard of any nation which was purely Mahomedan being able to enjoy them. A constitution depends upon the character of the people to whom it is applied, and there is no circumstance which influences those people more than the religion which they profess, and I will venture to say that there is no instance in the history of the world of any purely Mahomedan, or mainly Mahomedan, population flourishing under what we call popular institutions.

- Speech in the Free Trade Hall, Manchester (16 April 1884), quoted in The Times (17 April 1884), p. 6

- We know Mr. Gladstone is an authority...that the Soudanese are struggling for their liberty. My impression of the matter is that the Soudanese are struggling for abridging the liberty of other people in the shape of the slave trade. (Laughter and cheers.)

- Speech in Plymouth on the Mahdist War (4 June 1884), quoted in The Times (5 June 1884), p. 6

- [W]hen I am told that my ploughmen are capable citizens, it seems to me ridiculous to say that educated women are not just as capable. A good deal of the political battle of the future will be a conflict between religion and unbelief: & the women will in that controversy be on the right side.

- Letter to Lady John Manners (14 June 1884), quoted in Paul Smith (ed.), Lord Salisbury on Politics: A Selection From His Articles in the Quarterly Review, 1860–83 (1972), p. 18, footnote

- You only have to go on working together as you have hitherto done, not allowing yourselves to be discouraged by any temporary reverses, not believing that any evil day, when it comes, must necessarily be permanent, but trying to convince—what is truth—that in the steadiness and stability of our institutions lies the great hope of industry of the working man (hear, hear)—trying to impress upon him that any adventurous policy or change at home which sets class against class, and fills all men's minds with disquiet and mistrust, is a dangerous thing for industry, and is the most certain poison which trade and commerce can suffer under. (Hear, hear.) If you can bring these facts before the minds of the working men they will observe as time goes on that a policy which appeals to discontent does not produce internal prosperity. (Hear, hear.) They will see that a policy which neglects the Empire of England does not open to us the markets of the world. (Hear, hear.) They will see that the path of national prosperity and national dishonour are not parallel, and they will recognise with this that the party which sustained the old institutions—institutions under which England grew great—which upholds the traditions under which her name has ever been illustrious abroad—that to that party most rightly belongs, and most safely can be confided, the interests of the complicated industry and commerce on which the existence of so many millions of our countrymen depends. (Loud cheers.)

- Speech in Glasgow (1 October 1884), quoted in The Times (2 October 1884), p. 7

- Now the terrible responsibility and blame rests upon the Government, because they were warned in March and April of the danger to General Gordon; because they received every intimation which men could reasonably look for that his danger would be extreme; and because they delayed from March and April right down to the 15th of August before they took a single measure to relieve him. What were they doing all that time? It is very difficult to conceive. ... Some people think there were divisions in the Cabinet, and that, after division on division, a decision was put off lest the Cabinet should be broken up. I am rather inclined to think that it was due to the peculiar position of the Prime Minister [William Gladstone]. He came in as the apostle of the Midlothian campaign, loaded with all the doctrines and all the follies of that pilgrimage.

- Speech in the House of Lords after the Fall of Khartoum (26 February 1885)

- Egypt stands in a peculiar position. It is the road to India. The condition of Egypt can never be indifferent to us; and, more than that, after all the sacrifices that we have made, after all the efforts that this country has put forth, after the position that we have taken up in the eyes of the world, we have a right, and it is our duty to insist upon it, that our influence shall be predominant in Egypt.

- Speech in the House of Lords (26 February 1885)

- My idea of the manner of dealing with Russia is not to extract from her promises which she will not keep (cheers), but to say to her, "There is a point to which you shall not go (cheers), and if you go we will spare neither men nor money until you go back." (Loud cheers.)

- Speech in Wrexham (21 April 1885), quoted in The Times (22 April 1885), p. 10

- Remember what it is for which we struggle. In the first place, it is for the maintenance of religion. You know there is an old proverb, "You may know a man by his associates," and you may notice, if you will follow the course of literature, that infidels are always Liberals.

- Speech in Welshpool, Montgomeryshire (22 April 1885), quoted in The Times (23 April 1885), p. 8

- He certainly agrees with your Majesty in thinking that the [Irish] Nationalists cannot be trusted: and that any bargain with them would be full of danger.

- Letter to Queen Victoria (20 July 1885), quoted in Viscount Gladstone, After Thirty Years (1928), p. 392

- [I]t is idle to attempt to dispose of a particular proposal by saying that it is Socialistic. Prove that it is against public policy; show that it discourages thrift; above all, show that it interferes with justice, that it benefits one class by injuring another—do these things, and you have proved your case. But do not imagine that by merely affixing to it the reproach of Socialism you can seriously affect the progress of any great legislative movement, or destroy those high arguments which are derived from the noblest principles of philanthropy and religion.

- Speech in the House of Lords (31 July 1885), defending the Housing of the Working Classes Bill

- If I like to drink beer it is no reason that I should be prevented from taking it because my neighbour does not like it. If you sacrifice liberty on the matter of alcohol you will eventually sacrifice it on more important matters also, and those advantages of civil and religious liberty for which we have fought hard will gradually be whittled away.

- Speech in Newport, Montgomeryshire (7 October 1885), quoted in The Times (8 October 1885), p. 7

- As to religious education, which Mr. Morley desires to get rid of, it is one of our most cherished privileges. (Loud cheers.) I am not speaking for my own alone. What I claim I would extend equally to the Nonconformists of Wales or the Roman Catholics of Ireland. But I do claim that whatever Church or form of Christianity they belong to, there should be given the opportunity to educate the people in the belief of Christianity which they profess, instead of giving them a lifeless, boiled down, mechanical, unreal religious teaching which is prevalent in the Board schools.

- Speech in Newport, Montgomeryshire (7 October 1885), quoted in The Times (8 October 1885), p. 7

- The traditions of our party are well known. The integrity of the Empire is more precious to us than any other possessions. (Cheers.) If I may add another consideration, we are bound by motives not only of expediency, not only of legal principles, but by motives of honour, to protect the minority, if such exist, who have fallen into unpopularity and danger because they have maintained either as champions or as instruments the policy which England has deliberately elected to pursue. (Cheers.)

- Speech in Mansion House, London (9 November 1885), quoted in The Times (10 November 1885), p. 6

- [S]omehow or other another prospect of unlimited vestry confiscation, something like the three acres and a cow, seems to have affected the electorate of this country. ... The discussion that has taken place has pretty well convinced those who did not know it before, that small tenancies were not the source of unbounded wealth and happiness to those who had the privilege of enjoying them; and I have noticed that the offer has fallen perfectly flat on those agricultural labourers who know what they are doing. Their observation was, "Give me three or four acres? I cannot live upon that."

- Speech in St. Stephen's Club, London (23 November 1885), quoted in The Times (24 November 1885), p. 7

- I never admired the political transformation scenes of 1829, 1846, 1867; and I certainly do not wish to be the chief agent in adding a fourth to the history of the Tory party.

- Letter to Lord Bath rejecting Irish Home Rule (27 December 1885), quoted in H. J. Hanham (ed.), The Nineteenth-Century Constitution, 1815-1914: Documents and Commentary (1969), p. 235

- The disease is not in Ireland. The disease is here—in Westminster. If you had pursued—if you would now pursue—any steady, unvarying, and consistent policy with regard to Ireland, you would find that the problems that that country offered to you in respect of government are not greater than the problems of government which have been successively overcome by every Government in the world. There is nothing in them of that extraordinary or extreme character that should set at defiance the resources of civilization. But it is necessary, above all things, that the play of our Party system shall not call into question the foundations upon which our polity rests. It is necessary that men should not be able to speculate on the change of Party to Party in the hope of altering the fundamental laws on which the union of the United Kingdom is based. If you have instability of purpose, if you have a policy shifting from five years to five years with each change in the wheel of political fortune, or the humour of political Parties in this country, you are drifting straight to a ruin which will engulf England and Ireland alike. Your hope is not so much in this or that particular plan or panacea for restoring order, or maintaining law, or reviving the conditions of civilized life in Ireland. Your hope is in this—that Parliament shall school itself to adopt a steady, consistent policy, and maintain it when it is once adopted. A resolution of that kind manfully carried out will restore that prosperity to which Ireland has for so long been a stranger.

- Speech in the House of Lords (12 January 1886)

- There are other countries in the world where your Empire is maintained by the faith which men have that those who take your side will be supported and upheld. Whenever the thought crosses you that you can safely abandon those who for centuries have taken your side in Ireland, I beseech you to think of India, I beseech you to think of the effect it will have if the suspicion can get abroad there that, should convenience once dictate such a policy, like the Loyalists of Ireland, will be flung aside like a sucked orange when their purpose has been fulfilled.

- Speech to a Conservative Party banquet against Irish Home Rule (18 February 1886), quoted in Stephen J. Lee, Gladstone and Disraeli (2005), p. 140

- [T]here is no middle term between government at Westminster and independent and entirely separate government at Dublin. (Cheers.) If you do not have a government in some form or other issuing from this centre, you must have absolute separation.

- Speech to a meeting convened by the Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union in the Opera House, Haymarket (14 April 1886), quoted in The Times (15 April 1886), p. 6

- There is a state in Europe which has had very often to hear the word autonomy, which has had more than once to grant Home Rule and to see separation following Home Rule. The state I have referred to is...the Empire of Turkey. (Cheers.) Let any one who thinks that separation is consistent with the strength and prosperity of the country look to its effect, its repeated effect when applied to another country. ... Turkey had first to give autonomy to Roumania, autonomy was followed by independence; it had to give autonomy to Servia, autonomy was followed by independence. ... Turkey is a decaying empire; England, I hope, is not. (Cheers.) But I want to point out to you by a striking and conspicuous example that this process of giving autonomy to provinces which is certain to slide into separation is not consistent with the prosperity or the maintenance of an empire. (Cheers.)

- Speech to a meeting convened by the Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union in the Opera House, Haymarket (14 April 1886), quoted in The Times (15 April 1886), p. 6

- We give our confidence to the people of England because they have always been loyal to the Queen, have always loved the law, and have always been passionately attached to the Empire. (Cheers.) Has that characterised the Irish dominant faction? ... Why they have always sought support from time to time from whatever nation happened to be in hostility to England—first the Spaniards, then the French, and now the Americans.

- Speech to a banquet of the Merchant Taylors' Company, London (10 May 1886), quoted in The Times (11 May 1886), p. 12

- I believe that any repeal of the Union [with Ireland] or any substantial tampering with it is fraught with danger to this country. That has always been the opinion of the Conservative party and always will remain so. It is granting a separate government and separate executive. ... The result is that the [Protestant] minority will not only have laws passed of which they disapprove, but they will have to depend on the toleration and good will of their enemies for the common privileges of civilised life and securities.

- Speech to a banquet of the Merchant Taylors' Company, London (10 May 1886), quoted in The Times (11 May 1886), p. 12

- The truth is that the connection of Ireland with England has been full of trouble, and I fear there is no remedy. ... It is a chronic disease, and even if it is not to be cured we have proved in the past that we can get on with it and yet carry on our Empire to a vast pitch of prosperity. What has been done in the past can be done in the future. ... [D]o not let us attempt to cure it by a measure which will put this island into a condition which never during 700 years of our history has existed—which will hand over those who have had the courage to defend us to the maltreatment of their worst enemies, and which will establish at our very doors a post—a hostile post—which will be at the pleasure of any foreign power which may sometimes be hostile to us.

- Speech to a banquet of the Merchant Taylors' Company, London (10 May 1886), quoted in The Times (11 May 1886), p. 12

- Mr. Parnell said the other night, that Ireland is a "nation". Well, if a nation only means a certain number of individuals collected between certain latitudes and longitudes, I admit in that sense Ireland is a nation. But if there is anything further necessary—if to make a nation you require a past united history, traditions in which you can all join, achievements of which you all are proud, interests which you share in common, and sympathies which belong to all—then emphatically Ireland is not a nation; Ireland is two nations.

- Speech to the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations in St. James's Hall, London (15 May 1886), quoted in The Times (17 May 1886), p. 6

- Confidence depends upon the people in whom you are to confide. You would not confide free representative institutions to the Hottentots, for instance. Nor, going higher up the scale, would you confide them to the Oriental nations whom you are governing in India—although finer specimens of human character you will hardly find than some of those who belong to these nations, but who are simply not suited to the particular kind of confidence of which I am speaking. Well, I doubt whether you could confide representative institutions to the Russians with any great security. You have done it to the Greeks, but I do not know whether the result has been absolutely what you wish. And when you come to narrow it down you will find that this which is called self-government, but which is really government by the majority, works admirably well when it is confided to people who are of Teutonic race, but that it does not work so well when people of other races are called upon to join in it.

- Speech to the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations in St. James's Hall, London (15 May 1886), quoted in The Times (17 May 1886), p. 6