Loading AI tools

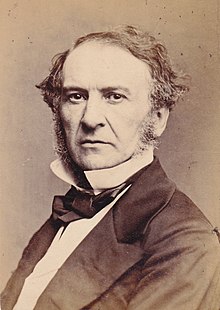

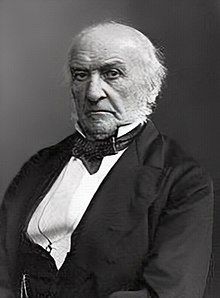

William Ewart Gladstone (29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British Liberal politician and Prime Minister (1868–1874, 1880–1885, 1886 and 1892–1894). He was a notable political reformer, known for his populist speeches, and was for many years the main political rival of Benjamin Disraeli.

1840s

- I have already expressed my opinion that the interference of the noble Lord should have been for the suppression of the trade in opium, and that the war was not justified by any excesses committed on the part of the Chinese. I have already stated, that although the Chinese were undoubtedly guilty of much absurd phraseology, of no little ostentatious pride, and of some excess, justice, in my opinion, is with them, and, that whilst they, the Pagans, and semi-civilized barbarians, have it, we, the enlightened and civilized Christians, are pursuing objects at variance both with justice, and with religion.

- Speech in the House of Commons (8 April 1840) against the First Opium War

- The right hon. Gentleman has argued, that the adoption of the plan proposed by the Government would confer advantage on the consumer, would increase the revenue, and would give increased scope to the industry of the manufacturer. We, Sir, argue, that with an amount of benefit to the revenue altogether inconsiderable, with a slight, nay an imperceptible relief to the consumer, and with detriment to the sure interests of the British manufacturer, you are asked to abandon what is nothing less than a great principle of humanity, that has received the most solemn sanction of the Legislature, the principle of hostility to the slave-trade and to slavery.

- Speech in the House of Commons (10 May 1841). Gladstone was opposed to the equalisation of the duty on foreign and colonial sugar because he believed that it would promote the slave trade

- I have clung to the notion of a conscience, and a Catholic conscience, in the State, until that idea has become in the general mind so feeble, as to be absolutely inappreciable in the movement of public affairs. I do not know whether there is one man opposing the Maynooth Bill upon that principle. When I have found myself the last man in the ship, I think that I am free to leave it.

- Letter to John Henry Newman (19 April 1845), quoted in The Correspondence of Henry Edward Manning and William Ewart Gladstone: Volume Two, 1844–1853, ed. Peter C. Erb (2013), p. 141

- Ireland, Ireland! That cloud in the west! That coming storm! That minister of God's retribution upon cruel, inveterate, and but half-atoned injustice! Ireland forces upon us those great social and great religious questions—God grant that we may have courage to look them in the face, and to work through them.

- Letter to his wife, Catherine Gladstone (12 October 1845), quoted in John Morley, The Life of Wiliam Ewart Gladstone, Volume I (1903), p. 383

1850s

- I believe the slave trade to be by far the foulest crime that taints the history of mankind in any Christian or pagan country.

- Speech in the House of Commons (19 March 1850)

- This is the negation of God erected into a system of Government.

- A letter to the Earl of Aberdeen, on the state prosecutions of the Neapolitan government (7 April 1851), p. 9

- From the ancient strife of territorial acquisition we are labouring, I trust and believe, to substitute another, a peaceful and a fraternal strife among nations, the honest and the noble race of industry and art.

- An Examination of the official reply of the Neapolitan Government (1852), p. 50

- [I]f it be true that, at periods now long past, England has had her full share of influence in stimulating by her example the martial struggles of the world, may she likewise be forward, now and hereafter, to show that she has profited by the heavy lessons of experience, and to be—if, indeed, in the designs of Providence, she is elected to that office—the standard-bearer of the nations upon the fruitful paths of peace, industry, and commerce.

- An Examination of the official reply of the Neapolitan Government (1852), p. 50

- [W]hile we have sought to do justice to the great labouring community of England by further extending their relief from indirect taxation, we have not been guided by any desire to put one class against another; we have felt we should best maintain our own honour, that we should best meet the views of Parliament, and best promote the interests of the country, by declining to draw any invidious distinction between class and class, by adopting it to ourselves as a sacred aim, to diffuse and distribute—burden if we must; benefit if we may—with equal and impartial hand; and we have the consolation of believing that by proposals such as these we contribute, as far as in us lies, not only to develop the material resources of the country, but to knit the hearts of the various classes of this great nation yet more closely than heretofore to that Throne and to those institutions under which it is their happiness to live.

- Speech in the House of Commons (18 April 1853)

- When we speak of general war, we don't mean real progress on the road of freedom, the real, moral, and social advancement of man, achieved by force. This may be the intention, but how rarely is it the result of general war! We mean this:—That the face of nature is stained with human gore—we mean that taxation is increased and industry diminished—we know that it means that burdens unreasonable and untold are entailed on late posterity—we know that it means that demoralization is let loose, that families are broken up, that lusts become unbridled in every country to which that war is extended.

- Speech at Manchester (12 October 1853), quoted in The Times (13 October 1853), p. 7

- All the terms that we demanded have, since the war began, been substantially conceded...My hon. Friend...[said] that we must obtain a success in order that we may secure better terms; but that is not the public and popular sentiment; the popular feeling is, that as to terms there is no great matter at issue, but that what you want is more military success...It is not only indefensible—it is hideous, it is anti-Christian, it is immoral, it is inhuman; and you have no right to make war simply for what you call success. If, when you have obtained the objects of the war, you continue it in order to obtain military glory...I say you tempt the justice of Him in whose hands the fates of armies are as absolutely lodged as the fate of the infant slumbering in its cradle; you tempt Him to launch upon you His wrath; and if this be courage, I, for one, have no courage to enter upon such a course. I believe it to be alike guilty and unwise.

- Speech in the House of Commons (24 May 1855) on the Crimean War

- There is but one way of maintaining permanently what I may presume to call the great international policy and law of Europe—but one way of keeping within bounds any one of the Powers possessed of such strength as France, England, or Russia, if it be bent on an aggressive policy, and that is, by maintaining not so much great fleets, or other demonstrations of physical force, which I believe to be really an insignificant part of the case, but the moral union—the effective concord of Europe.

- Speech in the House of Commons (3 August 1855)

- There is a policy going a begging; the general policy that Sir Robert Peel in 1841 took office to support—the policy of peace abroad, of economy, of financial equilibrium, of steady resistance to abuses, and promotion of practical improvements at home, with a disinclination to questions of reform, gratuitously raised.

- Letter to Whitwell Elwin (2 December 1856), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone, Volume I (1903), p. 553

- To maintain a steady surplus of income over expenditure—to lower indirect taxes when excessive in amount for the relief of the people and bearing in mind the reproductive power inherent in such operations—to simplify our fiscal system by concentrating its pressure on a few well chosen articles of extended consumption—and to conciliate support to the income tax by marking its temporary character and by associating it with beneficial changes in the laws: these aims have been for fifteen years the labour of our life.

- Memorandum (14 February 1857), quoted in John Brooke and Mary Sorensen (eds.), The Prime Minister's Papers: W. E. Gladstone. III: Autobiographical Memoranda 1845–1866 (1978), p. 215

- War taken at the best is a frightful scourge to the human race; but because it is so the wisdom of ages has surrounded it with strict laws and usages, and has required formalities to be observed which shall act as a curb upon the wild passions of man, to prevent that scourge from being let loose unless under circumstances of full deliberation and from absolute necessity. You have dispensed with all these precautions.

- Speech in the House of Commons against the Second Opium War (3 March 1857)

- At a time when sentiments are so much divided, every man I trust, will give his vote with the recollection and the consciousness that it may depend upon his single vote whether the miseries, the crimes, the atrocities that I fear are now proceeding in China are to be discountenanced or not. We have now come to the crisis of the case. England is not yet committed. But if an adverse vote be given...England will have been committed. With you then, with us, with every one of us, it rests to show that this House, which is the first, the most ancient, and the noblest temple of freedom in the world, is also the temple of that everlasting justice without which freedom itself would be only a name or only a curse to mankind. And I cherish the trust and belief that when you, Sir, rise in your place to-night to declare the numbers of the division from the chair which you adorn, the words which you speak will go forth from the walls of the House of Commons, not only as a message of mercy and peace, but also as a message of British justice and British wisdom, to the farthest corners of the world.

- Speech in the House of Commons against the Second Opium War (3 March 1857)

- Decision by majorities is as much an expedient, as lighting by gas.

- Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (Oxford University Press, 1858), p. 116.

- Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place.

- Letter to his brother Robertson of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool (1859), as quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 241

- What has been the state of things since 1853? It is useless to blink the fact that not merely within the circle of the public departments and of Cabinets, but throughout the country at large, and within the precincts of this House—the guardians of the purse of the people—the spirit of public economy has been relaxed; charges upon the public funds of every kind have been admitted from time to time upon slight examination; every man's petition and prayer for this or that expenditure has been conceded with a facility which I do not hesitate to say you have only to continue for some five or ten years longer in order to bring the finances of the country into a state of absolute confusion.

- Speech in the House of Commons (21 July 1859) against Benjamin Disraeli's Budget

1860s

- I am certain, from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account-keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned need not be referred to afterwards.

- Letter to Mrs. Gladstone (14 January 1860), as quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 242

- [T]he great aim—the moral and political significance of the act, and its probable and desired fruit in binding the two countries together by interest and affection. Neither you nor I attach for the moment any superlative value to this Treaty for the sake of the extension of British trade. ... What I look to is the social good, the benefit to the relations of the two countries, and the effect on the peace of Europe.

- Letter to Richard Cobden (c. 1860), quoted in H. C. G. Matthew, Gladstone, 1809–1874 (1986), p. 113

- Sir, there was once a time when close relations of amity were established between the Governments of England and France. It was in the reign of the later Stuarts; and it marks a dark spot in our annals, because it was an union formed in a spirit of domineering ambition on the one side, and of base and vile subserviency on the other. But that, Sir, was not an union of the nations; it was an union of the Governments. This is not be an union of the Governments; it is to be an union of the nations.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the Anglo-French Commercial Treaty (10 February 1860)

- Our proposals involve a great reform in our tariff, they involve a large remission of taxation, and last of all, though not least, they include that Commercial Treaty with France... By pursuing such a course as this it will be in your power to scatter blessings among the people, and blessings which are among the soundest and most wholesome of all the blessings at your disposal, because in legislation of this kind you are not forging mechanical helps for men, nor endeavouring to do that for them which they ought to do for themselves; but you are enlarging their means without narrowing their freedom, you are giving value to their labour, you are appealing to their sense of responsibility, and you are not impairing their sense of honourable self-dependence.

- Speech in the House of Commons (10 February 1860)

- For my own part I am deeply convinced that all excess in the public expenditure beyond the legitimate wants of the country is not only a pecuniary waste—for that is a comparatively trifling matter—but a great political and a great moral evil. It is a characteristic of the mischief which arise from financial prodigality, that they creep onwards with a noiseless and surreptitious step; that they are unseen and unfelt until they have reached a magnitude absolutely overwhelming, and then at length, we see them, as perhaps they now exist in the case of one at least among the great European nations, so fearful and menacing in their aspect that they seem to threaten the very foundations of national existence.

- Speech in the House of Commons (15 April 1861)

- [T]he right hon. Gentleman the Member for Stroud says of this Budget...[that] it is a mortal stab at the Constitution. I want to know to what Constitution does it give a mortal stab? In my opinion it gives no mortal stab, and no stab at all. But, on the contrary, so far as it alters anything in the most recent practice, it alters in the direction of restoring that good old Constitution which took its root in Saxon times, which grew under the Plantagenets, which endured the hard rule of the Tudors, and resisted the aggressions of the Stuarts, and which has now come to such perfect maturity under the rule of the House of Brunswick.

- Speech in the House of Commons (16 May 1861)

- We may have our own opinions about slavery; we may be for or against the South; but there is no doubt that Jefferson Davis and other leaders of the South have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more than either—they have made a Nation... We may anticipate with certainty the success of the Southern States so far as regards their separation from the North. I cannot but believe that that event is as certain as any event yet future and countingent can be.

- Speech on the American Civil War, Town Hall, Newcastle upon Tyne (7 October 1862), quoted in The Times (9 October 1862), pp. 7-8

- I mean this, that together with the so-called increase of expenditure there grows up what may be termed a spirit which, insensibly and unconsciously perhaps, but really, affects the spirit of the people, the spirit of parliament, the spirit of the public departments, and perhaps even the spirit of those whose duty it is to submit the estimates to parliament.

- Speech in the House of Commons (16 April 1863), quoted in The Life of William Ewart Gladstone. Volume II (1903) by John Morley, p. 62

- But how is the spirit of expenditure to be exorcised? Not by preaching; I doubt if even by yours. I seriously doubt whether it will ever give place to the old spirit of economy, as long as we have the income-tax. There, or hard by, lie questions of deep practical moment.

- Letter to Richard Cobden (5 January 1864), quoted in The Life of William Ewart Gladstone Volume II (1903) by John Morley, p. 62

- I venture to say that every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness or of political danger is morally entitled to come within the pale of the Constitution. ...fitness for the franchise, when it is shown to exist—as I say it is shown to exist in the case of a select portion of the working class—is not repelled on sufficient grounds from the portals of the Constitution by the allegation that things are well as they are. I contend, moreover, that persons who have prompted the expression of such sentiments as those to which I have referred, and whom I know to have been Members of the working class, are to be presumed worthy and fit to discharge the duties of citizenship, and that to admission to the discharge of those duties they are well and justly entitled.

- Speech in the House of Commons (11 May 1864)

- What are the qualities which fit a man for the exercise of a privilege such as the franchise? Self-command, self-control, respect for order, patience under suffering, confidence in the law, regard for superiors.

- Speech in the House of Commons (11 May 1864)

- As to his Goddess Reason, I understand by it simply an adoption of what are called on the continent the principles of the French Revolution. These we neither want nor warmly relish in England.

- Letter to Henry Edward Manning after Giuseppe Garibaldi's visit to Britain (c. July 1864), quoted in The Correspondence of Henry Edward Manning and William Ewart Gladstone: Volume Three, 1861–1875, ed. Peter C. Erb (2013), p. 28

- At last, my friends, I am come amongst you. And I am come…unmuzzled.

- Speech to the electors of South Lancashire. (18 July 1865)

- I am a member of a Liberal Government. I am in association with the Liberal party. I have never swerved from what I conceived to be those truly Conservative objects and desires with which I entered life. I am, if possible, more fondly attached to the institutions of my country than I was when as a boy I wandered among the sand-hills of Seaforth or the streets of Liverpool. But experience has brought with it its lessons. I have learnt that there is wisdom in a policy of trust, and folly in a policy of mistrust. I have not refused to receive the signs of the times. I have observed the effect that has been produced by Liberal legislation, and if we are told...that all the feelings of the country are in the best and broadest sense Conservative,—that is to say, that the people value the country and the laws and institutions of the country; if we are told that, I say honesty compels us to admit that result has been brought about by Liberal legislation.

- Speech at Liverpool (18 July 1865), quoted in The Times (19 July 1865), p. 11.

- The position of England, gentlemen, is a peculiar position in the world. England has inherited from bygone ages more, perhaps, of what was most august and venerable in those ages than any other European country, and at the same time that her traditions of the past are so rich and fruitful that all our minds and all our characters have both within our knowledge and beyond our knowledge been largely moulded by them. ... [G]eographically she stands with Europe on one side of her and America on the other, so she stands between those feudal institutions in which European society was formed, and which have given her hierarchy of class, and on the other side those principles of equality forming the basis of society in America.

- Speech to the Liverpool Liberal Association (6 April 1866), quoted in The Times (7 April 1866), p. 9

- It is sometimes said that the measure we propose is a democratic measure. The word “democracy” has very different senses, if by democracy be meant liberty—if by democracy be meant the extension to each man in his own sphere of every privilege and of every franchise that he can exercise with advantage to himself and with safety to the State,—then I must confess I don't see much to alarm us in the word democracy. (Cheers.) But if by democracy be meant the enthroning of ignorance against knowledge, the setting up of vice in opposition to virtue, the disregard of rank, the forgetfulness of what our fathers have done for us, indifference or coldness with regard to the inheritance we enjoy, then, Gentlemen, I for one—and I believe for all I have the honour to address—am in that sense the enemy of democracy.

- Speech to the Liverpool Liberal Association (6 April 1866), quoted in The Times (7 April 1866), p. 9

- My position then, Sir, in regard to the Liberal party is in all points the opposite of Earl Russell's. ... I have none of the claims he possesses. I came among you an outcast from those with whom I associated, driven from them, I admit, by no arbitrary act, but by the slow and resistless forces of conviction. I came among you, to make use of the legal phraseology, in pauperis forma. I had nothing to offer you but faithful and honourable service. ... You received me with kindness, indulgence, generosity, and I may even say with some measure of confidence. And the relation between us has assumed such a form that you never can be my debtors, but that I must for ever be in your debt.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the Second Reading of the Representation of the People Bill (27 April 1866)

- [T]here appeared to me to have grown up under the present Government a system of what I called, in regard to the public expenditure, making things pleasant all round. That means going from town to town, granting what this community wants, granting what that community wants, granting what the other community wants, and leaving out of sight that huge public which unfortunately has not got the voices and the advocates ready always to defend it against these local and particular claims, but of which it is our highest boast that we seek to be the advocates and the champions.

- Speech in Leigh, Lancashire (20 October 1868), quoted in The Times (21 October 1868), p. 11

- If you want to be served you must draw the distinction between those who want to serve you and those who don't, and if the electors of South Lancashire and of the country generally are contented to allow this method of expenditure to go on, this Continental system of feeding the desires of classes and portions of the community at the expense of the whole—it is idle for you to satisfy yourselves with vague and general promises. ... If that is to be the system on which public finance is to be administered you must be prepared to resign all hopes of remission of taxation, even in good years, and in bad years you must look for a steady augmentation of the income-tax.

- Speech in Leigh, Lancashire (20 October 1868), quoted in The Times (21 October 1868), p. 11

- [W]e find and we know that this attempt in Ireland to make the power and influence of the State the means of supporting one creed against another has been the plague and the scourge of the country—has divided man from man, class from class, kingdom from kingdom, and in this great, and ancient, and noble empire has had the effect of now exhibiting us to the world as a divided country—three kingdoms, two of which we are indeed heartily united and associated, but the third of which offers to mankind a spectacle painful and full of schism and destruction within itself, and alienation and estrangement as regards the Throne and Constitution of this realm.

- Speech in the assembly-rooms at Wavertree (14 November 1868), quoted in The Times (16 November 1868), p. 5

- The only means which have been placed in my power of "raising the wages of colliers" has been by endeavouring to beat down all those restrictions upon trade which tend to reduce the price to be obtained for the product of their labour, & to lower as much as may be the taxes on the commodities which they may require for use or for consumption. Beyond this I look to the forethought not yet so widely diffused in this country as in Scotland, & in some foreign lands; & I need not remind you that in order to facilitate its exercise the Government have been empowered by Legislation to become through the Dept. of the P.O. the receivers & guardians of savings.

- Letter to Daniel Jones, an unemployed collier who complained of unemployment and of low wages (20 October 1869) as quoted in The Gladstone Diaries: With Cabinet Minutes and Prime-ministerial Correspondence: 1869-June 1871 Vol. 7 (1982) by H. C. G. Matthew, p. lxxiv

1870s

- Hephaistos bears in Homer the double stamp of a Nature-Power, representing the element of fire, and of an anthropomorphic deity who is the god of art at a period when the only fine art known was in works of metal produced by the aid of fire.

- Jeventus Mundi: The Gods and Men of the Heroic Age (1870) p. 289.

- The transfer of the allegiance and citizenship, of no small part of the heart and life, of human beings from one sovereignty to another, without any reference to their own consent, has been a great reproach to some former transactions in Europe; has led to many wars and disturbances; is hard to reconcile with considerations of equity; and is repulsive to the sense of modern civilization.

- Letter to Lord Granville (24 September 1870), quoted in Harold Temperley and Lillian M. Penson, Foundations of British Foreign Policy from Pitt (1792) to Salisbury (1902) or Documents, Old and New (1938), pp. 325–326

- I am much oppressed with the idea that this transfer of human beings like chattels should go forward without any voice from collective Europe if it be disposed to speak.

- Letter to Lord Granville on Germany's annexation of Alsace-Lorraine (30 September 1870), quoted in Agatha Ramm (ed.), The Gladstone–Granville Correspondence [1952] (1998), p. 135

- In moral forces, and in their growing effect upon European politics, I have a great faith: possibly on that very account, I am free to confess, sometimes a misleading one.

- Letter to Lord Granville (8 October 1870), quoted in Harold Temperley and Lillian M. Penson, Foundations of British Foreign Policy from Pitt (1792) to Salisbury (1902) or Documents, Old and New (1938), p. 323

- On the whole, it seems reasonable to hope that the practical character of our Teutonic cousins [Germany], together with their huge actual mass of domestic sorrows, will assist them to settle down into a mood of peace and goodwill. But whether they do or not, it is idle to apprehend that they have before them a career of universal conquest or absolute predominance, and that the European family is not strong enough to correct the eccentricities of its pecant and obstreperous members.

- ‘Germany, France, and England’, Edinburgh Review (October 1870), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Gleanings of Past Years, 1843–78. Vol. IV. Foreign (1879), p. 249

- Certain it is that a new law of nations is gradually taking hold of the mind, and coming to sway the practice, of the world; a law which recognises independence, which frowns upon aggression, which favours the pacific, not the bloody settlement of disputes, which aims at permanent and not temporary adjustments; above all, which recognises, as a tribunal of paramount authority, the general judgment of civilised mankind. It has censured the aggression of France; it will censure, if need arise, the greed of Germany. “Securus judicat orbis terrarum.” It is hard for all nations to go astray. Their ecumenical council sits above the partial passions of those, who are misled by interest, and disturbed by quarrel. The greatest triumph of our time, a triumph in a region loftier than that of electricity and steam, will be the enthronement of this idea of Public Right, as the governing idea of European policy; as the common and precious inheritance of all lands, but superior to the passing opinion of any.

- ‘Germany, France, and England’, Edinburgh Review (October 1870), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Gleanings of Past Years, 1843–78. Vol. IV. Foreign (1879), pp. 256–257

- I am inclined to say that the personal attendance and intervention of women in election proceedings, even apart from any suspicion of the wider objects of many of the promoters of the present movement, would be a practical evil not only of the gravest, but even of an intolerable character.

- Speech in the House of Commons on the Women's Disabilities Bill (3 May 1871)

- In London it was not the interests of class which were specially concentrated. It was there that wealth was all-powerful; and wealth has taken desperate offence at their actions during the present year because the Government recommended to Parliament that power in the English army shall no longer be the prize of wealth, but the reward of merit.

- Speech in Whitby on the Cardwell Reforms (2 September 1871), quoted in The Times (4 September 1871), p. 12

- [T]he establishment of freedom of trade and of a general disposition to remove from trade every possible restriction and every possible burden...has been the main agent in raising the commerce of the United Kingdom to that extraordinary position it has now attained. I apprehend that I am stating the matter very moderately if I put it thus, that in the course of the last 30 years our population has increased somewhere about 25 or 30 per cent., while our trade in the same period has increased in the ratio of certainly something not much under 400 per cent.

- Speech in Wakefield (5 September 1871), quoted in The Times (6 September 1871), p. 3

- Not a drop of blood runs in my veins except Scotch blood, and a large share of my heart ever has belonged, and ever will belong, to Scotland.

- Speech in Aberdeen upon receiving the freedom of the city (26 September 1871), quoted in The Times (27 September 1871), p. 6

- They are not your friends, but they are your enemies in fact, though not in intention, who teach you to look to the Legislature for the radical removal of the evils that afflict human life... It is the individual mind and conscience, it is the individual character, on which mainly human happiness or misery depends. (Cheers.) The social problems that confront us are many and formidable. Let the Government labour to its utmost, let the Legislature labour days and nights in your service; but, after the very best has been attained and achieved, the question whether the English father is to be the father of a happy family and the centre of a united home is a question which must depend mainly upon himself. (Cheers.) And those who...promise to the dwellers in towns that every one of them shall have a house and garden in free air, with ample space; those who tell you that there shall be markets for selling at wholesale prices retail quantities—I won't say are imposters, because I have no doubt they are sincere; but I will say they are quacks (cheers); they are deluded and beguiled by a spurious philanthropy, and when they ought to give you substantial, even if they are humble and modest boons, they are endeavouring, perhaps without their own consciousness, to delude you with fanaticism, and offering to you a fruit which, when you attempt to taste it, will prove to be but ashes in your mouths. (Cheers.)

- Speech in Blackheath (28 October 1871), quoted in The Times (30 October 1871), p. 3

- The idea of abolishing Income Tax is to me highly attractive, both on other grounds & because it tends to public economy.

- Letter to H. C. E. Childers (3 April 1873)

- [I]f these islands were to be annexed they would present to us, in the most aggravated form, the difficulty arising from marked differences of race, which occurred already in some of our colonial possessions. Where the superior race was very large in numbers, and the less developed and less civilized race were small, the difficulty was little felt. In Porto Rico, for example, although there was a very large number of negroes—now, happily, no longer slaves—yet the number of Whites was extremely large in comparison, and the slave emancipation had been effected without difficulty. Jamaica was not like Porto Rico. The Whites were very small in number in Jamaica compared with the less developed race.

- Speech in the House of Commons (13 June 1873)

- [Y]ours is an ancient language, and the language is connected with an ancient history, and it is connected with an ancient music and with an ancient literature. I say that...it is a venerable relic of the past, and there is no greater folly circulating upon the earth, either at this moment or at any other time, than the disposition to under value the past and to break those links which unite the human beings of the present day with the generations that have passed away and have been called to their account. If we wish really to promote the progress of civilization never let us neglect, never let us undervalue, never let us cease to reverence the past. Rely upon it the man who does not worthily estimate his own dead forefathers will himself do very little to add credit or honour to his country... [Y]our laudable and patriotic efforts will come to be more and more understood and regarded by the English people at large, and that prosperity and honour will attend the meetings by which you endeavour to preserve and to commemorate the ancient history, the ancient deeds, and the ancient literature of your country, the Principality of Wales.

- Inaugural address to the opening of the Eisteddfod in Mold, of which Gladstone was President (19 August 1873), quoted in The Times (20 August 1873), p. 5

- For myself, I said, not in education only but in all things, including education, I prefer voluntary to legal machinery, when the thing can be well done either way.

- Letter to John Bright (21 August 1873), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone, Volume II (1903), p. 646

- Individual servitude, however abject, will not satisfy the Latin Church. The State must also be a slave.

- The Vatican Decrees in their Bearing on Civil Allegiance: A Political Exposition (November 1874), quoted in All Roads lead to Rome? The Ecumenical Movement (2004) by Michael de Semlyen

- The history of nations is a melancholy chapter, that is, the history of their Governments. I am sorrowfully of opinion that, though virtue of splendid quality dwells in high regions with individuals, it is chiefly to be found on a large scale with the masses; and the history of nations is one of the most immoral parts of human history.

- Letter to Olga Novikoff (1876), quoted in Olga Novikoff, Russian Memories (1916), p. 219

- A rational reaction against the irrational excesses and vagaries of scepticism may, I admit, readily degenerate into the rival folly of credulity. To be engaged in opposing wrong affords, under the conditions of our mental constitution, but a slender guarantee for being right.

- Homeric Synchronism : An Enquiry Into the Time and Place of Homer (1876), Introduction

- The operations of commerce are not confined to the material ends; that there is no more powerful agent in consolidating and in knitting together the amity of nations; and that the great moral purpose of the repression of human passions, and those lusts and appetites which are the great cause of war, is in direct relation with the understanding and application of the science which you desire to propagate.

- Speech to the Political Economy Club (31 May 1876) upon the centenary of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations

- [T]he effect of that [Crimean] war was ... to substitute a European conscience, expressed by collective guarantee and the concerted and general action of the European Powers for the sole and individual action of one of them. It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of that principle.

- Speech in the House of Commons (31 July 1876)

- I am delighted to see how many young boys and girls have come forward to obtain honourable marks of recognition on this occasion, — if any effectual good is to be done to them, it must be done by teaching and encouraging them and helping them to help themselves. All the people who pretend to take your own concerns out of your own hands and to do everything for you, I won't say they are imposters; I won't even say they are quacks; but I do say they are mistaken people. The only sound, healthy description of countenancing and assisting these institutions is that which teaches independence and self-exertion... When I say you should help yourselves — and I would encourage every man in every rank of life to rely upon self-help more than on assistance to be got from his neigbours — there is One who helps us all, and without whose help every effort of ours is in vain; and there is nothing that should tend more, and there is nothing that should tend more to make us see the beneficence of God Almighty than to see the beauty as well as the usefulness of these flowers, these plants, and these fruits which He causes the earth to bring forth for our comfort and advantage.

- Speech to the Hawarden Amateur Horticultural Society (17 August 1876), as quoted in "Mr. Gladstone On Cottage Gardening", The Times (18 August 1876), p. 9

- Let the Turks now carry away their abuses, in the only possible manner, namely, by carrying off themselves. Their Zaptiehs and their Mudirs, their Bimbashis and Yuzbashis, their Kaimakams and their Pashas, one and all, bag and baggage, shall, I hope, clear out from the province that they have desolated and profaned. This thorough riddance, this most blessed deliverance, is the only reparation we can make to those heaps and heaps of dead, the violated purity alike of matron and of maiden and of child; to the civilization which has been affronted and shamed; to the laws of God, or, if you like, of Allah; to the moral sense of mankind at large. There is not a criminal in a European jail, there is not a criminal in the South Sea Islands, whose indignation would not rise and over-boil at the recital of that which has been done, which has too late been examined, but which remains unavenged, which has left behind all the foul and all the fierce passions which produced it and which may again spring up in another murderous harvest from the soil soaked and reeking with blood and in the air tainted with every imaginable deed of crime and shame. That such things should be done once is a damning disgrace to the portion of our race which did them; that the door should be left open to their ever so barely possible repetition would spread that shame over the world!

- Let me endeavour, very briefly to sketch, in the rudest outline what the Turkish race was and what it is. It is not a question of Mohammedanism simply, but of Mohammedanism compounded with the peculiar character of a race. They are not the mild Mohammedans of India, nor the chivalrous Saladins of Syria, nor the cultured Moors of Spain. They were, upon the whole, from the black day when they first entered Europe, the one great anti-human specimen of humanity. Wherever they went a broad line of blood marked the track behind them, and, as far as their dominion reached, civilization vanished from view. They represented everywhere government by force as opposed to government by law. – Yet a government by force can not be maintained without the aid of an intellectual element. – Hence there grew up, what has been rare in the history of the world, a kind of tolerance in the midst of cruelty, tyranny and rapine. Much of Christian life was contemptuously left alone and a race of Greeks was attracted to Constantinople which has all along made up, in some degree, the deficiencies of Turkish Islam in the element of mind!

- Gladstone, William Ewart (1876). Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East. London: John Murray. p. 31. Retrieved on 2 September 2013.

- There is an undoubted and smart rally on behalf of Turkey in the metropolitan press. It is in the main representative of the ideas and opinions of what are called the upper ten thousand. From this body there has never on any occasion within my memory proceeded the impulse that has prompted, and finally achieved, any of the great measures which in the last half century have contributed so much to the fame and happiness of England. They did not emancipate the dissenters, Roman catholics, and Jews. They did not reform the parliament. They did not liberate the negro slave. They did not abolish the corn law. They did not take the taxes off the press. They did not abolish the Irish established church. They did not cheer on the work of Italian freedom and reconstitution. Yet all these things have been done; and done by other agencies than theirs, and despite their opposition.

- Letter to Olga Novikoff (17 October 1876), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone, Volume II (1903), p. 557

- There is, in fact, a great deal of resemblance between the system which prevails in Turkey and the old system of negro slavery. In some respects it is less bad than negro slavery, and in other respects a great deal worse. It is worse in this respect, that in the case of negro slavery, at any rate, it was a race of higher capacities ruling over a race of lower capacities; but in the case of this system, it is unfortunately a race of lower capacities which rules over a race of higher capacities.

- Speech in Hawarden (16 January 1877), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, The Sclavonic Provinces of the Ottoman Empire (1877)

- Sir, there were other days, when England was the hope of freedom. Wherever in the world a high aspiration was entertained, or a noble blow was struck, it was to England that the eyes of the oppressed were always turned—to this favourite, this darling home of so much privilege and so much happiness, where the people that had built up a noble edifice for themselves would, it was well known, be ready to do what in them lay to secure the benefit of the same inestimable boon for others. You talk to me of the established tradition and policy in regard to Turkey. I appeal to an established tradition, older, wider, nobler far—a tradition not which disregards British interests, but which teaches you to seek the promotion of those interests in obeying the dictates of honour and of justice.

- Speech in the House of Commons (7 May 1877)

- My opinion is and has long been that the vital principle of the Liberal party, like that of Greek art, is action, and that nothing but action will ever make it worthy of the name of a party.

- Letter to Lord Granville (19 May 1877), quoted in Agatha Ramm (ed.), The Gladstone–Granville Correspondence, 1876–1886 (1962), p. 40

- You will find, I think, that the predominating idea of Conservatism is the Egyptian principle of repose; but in our Liberal Party we have got the Greek idea of life and motion.

- Speech in Birmingham (31 May 1877), quoted in The Times (1 June 1877), p. 10

- Nonconformity...still supplies, to so great an extent, the backbone of British Liberalism.

- ‘The County Franchise, and Mr. Lowe Thereon’, The Nineteenth Century (November 1877), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Gleanings of Past Years, 1843-1878, Vol. I (1879), p. 158

- I feel with a peculiar sympathy all that relates to Scotland. The natives of Scotland, and all those who have Scotch blood in their veins—particularly if, like me, they only have Scotch blood in their veins—are not apt to forget the country from which they sprang. They know its great qualities. They know the solidity of its character.

- Speech in Westminster Palace Hotel (23 May 1878), quoted in The Times (24 May 1878), p. 12

- Liberty is never safe.

- Said to the Countess Russell and recorded in her diary, Lady John Russell: A Memoir (1910), edited by Desmond McCarthy and Agatha Russell. p. 252

- [T]he argument of unequal capacity does not tell so uniformly against the more numerous classes of the community as might be supposed. Whether from moral causes, or for whatever other reason, the popular judgment, on a certain number of important questions, is more just than that of the higher order.

- ‘Postscriptum on the County Franchise’, The Nineteenth Century (July 1878), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Gleanings of Past Years, 1843-1878, Vol. I (1879), p. 198

- As the British Constitution is the most subtile organism which has proceeded from the womb and the long gestation of progressive history, so the American Constitution is, so far as I can see, the most wonderful work ever struck off by the brain and purpose of man.

- Kin Beyond Sea, published in The North American Review, pp. 179-202

- It is [America] alone who, at a coming time, can, and probably will, wrest from us that commercial primacy. We have no title, I have no inclination, to murmur at the prospect... We have no more title against her than Venice, or Genoa, or Holland, has had against us.

- 'Kin beyond Sea', The North American Review Vol. 127, No. 264 (Sep.-Oct., 1878), p. 180

- The English people are not believers in equality; they do not, with the famous Declaration of July 4, 1776, think it to be a self-evident truth that all men are born equal. They hold rather the reverse of that proposition. At any rate, in practice they are what I may call determined inequalitarians; nay, in some cases, even without knowing it. Their natural tendency, from the very base of British society, and through all its strongly-built gradations, is to look upward... The sovereign is the highest height of the system; is, in that system, like Jupiter among the Roman gods, first without a second... It is the wisdom of the British Constitution to lodge the personality of its chief so high that none shall under any circumstances be tempted to vie, or to dream of vying, with it.

- 'Kin beyond Sea', The North American Review Vol. 127, No. 264 (Sep.-Oct., 1878), p. 202

- National injustice is the surest road to national downfall.

- Speech, Plumstead (30 November 1878) as quoted in Congressional Record, vol. 57, p. 4503

- The disease of an evil conscience is beyond the practice of all the physicians of all the countries in the world.

- Speech, Plumstead (30 November 1878) as quoted in The Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year, Volume 120, p. 208

- I think that the principle of the Conservative Party is jealousy of liberty and of the people, only qualified by fear; but I think the principle of the Liberal Party is trust in the people, only qualified by prudence.

- Speech at the opening of the Palmerston Club, Oxford (December 1878) as quoted in "Gladstone's Conundrums; The Statesman Answers Sundry Interesting Questions" in The New York Times (9 February 1879)

- [T]he great duty of a Government, especially in foreign affairs, is to soothe and tranquillize the minds of the people, not to set up false phantoms of glory which are to delude them into calamity, not to flatter their infirmities by leading them to believe that they are better than the rest of the world, and so to encourage the baleful spirit of domination; but to proceed upon a principle that recognises the sisterhood and equality of nations, the absolute equality of public right among them; above all, to endeavour to produce and to maintain a temper so calm and so deliberate in the public opinion of the country, that none shall be able to disturb it.

- Speech in Edinburgh (25 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 37.

- I wish to dissipate, if I can, the idle dreams of those who are always telling you that the strength of England depends, sometimes they say upon its prestige, sometimes they say upon its extending its Empire, or upon what it possesses beyond the seas. Rely upon it the strength of Great Britain and Ireland is within the United Kingdom.

- Speech in Edinburgh (25 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 46.

- Remember the rights of the savage, as we call him. Remember that the happiness of his humble home, remember that the sanctity of life in the hill villages of Afghanistan among the winter snows, are as sacred in the eye of Almighty God as are your own. Remember that He who has united you together as human beings in the same flesh and blood, has bound you by the law of mutual love, that that mutual love is not limited by the shores of this island, is not limited by the boundaries of Christian civilisation, that it passes over the whole surface of the earth, and embraces the meanest along with the greatest in its wide scope.

- Speech, Foresters' Hall, Dalkeith, Scotland (26 November 1879) as part of the Midlothian campaign; published in "Mr Gladstone's visit to Mid-Lothian: Meeting at the Foresters' Hall" (27 November 1879), The Scotsman, p. 6; also quoted in Life of Gladstone (1903) by John Morley, II, (p. 595)

- Here is my first principle of foreign policy: good government at home. My second principle of foreign policy is this—that its aim ought to be to preserve to the nations of the world—and especially, were it but for shame, when we recollect the sacred name we bear as Christians, especially to the Christian nations of the world—the blessings of peace. That is my second principle.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 115.

- In my opinion the third sound principle is this—to strive to cultivate and maintain, ay, to the very uttermost, what is called the concert of Europe; to keep the Powers of Europe in union together. And why? Because by keeping all in union together you neutralize and fetter and bind up the selfish aims of each. I am not here to flatter either England or any of them. They have selfish aims, as, unfortunately, we in late years have too sadly shown that we too have had selfish aims; but then common action is fatal to selfish aims. Common action means common objects; and the only objects for which you can unite together the Powers of Europe are objects connected with the common good of them all. That, gentlemen, is my third principle of foreign policy.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), pp. 115-116.

- My fourth principle is—that you should avoid needless and entangling engagements. You may boast about them, you may brag about them, you may say you are procuring consideration of the country. You may say that an Englishman may now hold up his head among the nations. But what does all this come to, gentlemen? It comes to this, that you are increasing your engagements without increasing your strength; and if you increase your engagements without increasing strength, you diminish strength, you abolish strength; you really reduce the empire and do not increase it. You render it less capable of performing its duties; you render it an inheritance less precious to hand on to future generations.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 116.

- My fifth principle is...to acknowledge the equal rights of all nations. You may sympathize with one nation more than another. Nay, you must sympathize in certain circumstances with one nation more than another. You sympathize most with those nations, as a rule, with which you have the closest connection in language, in blood, and in religion, or whose circumstances at the time seem to give the strongest claim to sympathy. But in point of right all are equal, and you have no right to set up a system under which one of them is to be placed under moral suspicion or espionage, or to be made the constant subject of invective. If you do that, but especially if you claim for yourself a superiority, a pharisaical superiority over the whole of them, then I say you may talk about your patriotism if you please, but you are a misjudging friend of your country, and in undermining the basis of the esteem and respect of other people for your country you are in reality inflicting the severest injury upon it.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), pp. 116-117.

- [My sixth principle is that] the foreign policy of England should always be inspired by the love of freedom. There should be a sympathy with freedom, a desire to give it scope, founded not upon visionary ideas, but upon the long experience of many generations within the shores of this happy isle, that in freedom you lay the firmest foundations both of loyalty and order; the firmest foundations for the development of individual character; and the best provision for the happiness of the nation at large.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 117.

- Of all the principles, gentlemen, of foreign policy which I attach the greatest value is the principle of the equality of nations; because, without recognising that principle, there is no such thing as public right, and without public international right there is no instrument available for settling the transactions of mankind except material force. Consequently, the principle of equality among nations lies, in my opinion, at the very basis and root of a Christian civilisation, and when that principle is compromised or abandoned, with it must depart our hopes of tranquillity and of progress for mankind.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 123.

- What did the two words "Liberty and Empire" mean in the Roman mouth? They meant simply this: liberty for ourselves, empire over the rest of mankind.

- Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in The Times (28 November 1878), p. 10. The Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli had proclaimed his policy as "Imperium et Libertas".

- The Chancellor of the Exchequer should boldly uphold economy in detail; and it is the mark of a chicken-hearted Chancellor when he shrinks from upholding economy in detail, when because it is a question of only two or three thousand pounds, he says it is no matter. He is ridiculed, no doubt, for what is called candle-ends and cheese-parings, but he is not worth his salt if he is not ready to save what are meant by candle-ends and cheese-parings in the cause of the country. No Chancellor of the Exchequer is worth his salt who makes his own popularity either his consideration, or any consideration at all, in administering the public purse. In my opinion, the Chancellor of the Exchequer is the trusted and confidential steward of the public. He is under a sacred obligation with regard to all that he consents to spend.

- Speech in Edinburgh (29 November 1879), quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 243

- [T]hat Chancellor of the Exchequer is the very man who comes down to corrupt whatever there is of financial virtue in us, and to instil into our minds those seductive and poisonous ideas that it does not, after all, matter very much if there is a deficit, and that it is extremely disagreeable when commerce is not in the most flourishing state to call upon the people to pay. Was that the practice of Sir Robert Peel? ... he came to Parliament and stood at his place in the House of Commons, pointed out the figures as they stood, and said to them—I ask you, will you resort to the "miserable expedient" of tolerating deficit, and of making provision by loans from year to year? That which he denounced as the "miserable expedient" has become the standing law, has become almost the financial gospel of the Government that is now in power.

- Speech in Edinburgh (29 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 152

- The Government of India is the most arduous and perhaps the noblest trust ever undertaken by a nation.

- Speech in Glasgow (5 December 1879), quoted in Michael Balfour, Britain and Joseph Chamberlain (1985), p. 212

1880s

- There was no instalment of Free Trade, which need be taken into our account, before 1842. ... I therefore take 1843 as the first operative year of the first instalment of Liberal legislation under what was called the new Tariff. The second instalment was the new Tariff of 1845. The third instalment was the repeal of the Corn Laws at the opening of 1849, together with the repeal of the Navigation Laws during the Parliamentary Session of that year. The fourth was the new Tariff of 1853, accompanied with the repeal of the Soap Duties and other changes. The fifth and last great instalment was granted by the Customs Act of 1860, which at length gave nearly universal effect to the following principles:

1. That neither on raw produce, nor on food, nor on manufactured goods, should any duty of a protective character be charged.

2. That the sums necessary to be levied for the purposes of revenue in the shape of Customs duty should be raised upon the smallest possible number of articles.- 'Free Trade, Railways, and the growth of Commerce', The Nineteenth Century, No. XXXVI (February 1880), quoted in The Nineteenth Century, Vol. VII (January–June 1880), p. 374

- Whether Protection is a universal poison, or whether it may be conceived to operate as food in cases where it is granted for a few years in order to shelter the first investments in a new industry, I do not now inquire. We at least have never seen or known it in that mitigated form. With us it has sheltered nothing but the most selfish instincts of class against the just demands of the public welfare. These it has supplied with strongholds, from whose portals our producers have too generally marched forth in the day of need, armed from head to foot with power and influence largely gotten at the expense of the community, to do battle with a perverted prowess, against nature, liberty, and justice.

- 'Free Trade, Railways, and the growth of Commerce', The Nineteenth Century, No. XXXVI (February 1880), quoted in The Nineteenth Century, Vol. VII (January–June 1880), p. 377

- We must fall back upon the broad, the incorruptible power of national liberty; that we decline to recognise any class whatever, be they peers or be they gentry, be they what you like, as entitled to direct the destinies of this nation against the will of the nation.

- Speech at Pathhead, Scotland (23 March 1880), quoted in Political Speeches in Scotland, March and April 1880 (1880), p. 268

- [T]he dispositions which led us to become parties to the arbitration on the Alabama case are still with us the same as ever; that we are not discouraged; that we are not damped in the exercise of these feelings by the fact that we were amerced, and severely amerced, by the sentence of the International Tribunal; and that, although we may think the sentence was harsh in its extent, and unjust in its basis, we regard the fine imposed on this country as dust in the balance compared with the moral value of the example set when these two great nations of England and America—which are among the most fiery and the most jealous in the world with regard to anything that touches national honour—went in peace and concord before a judicial tribunal to dispose of these painful differences, rather than to resort to the arbitrament of the sword.

- Speech in the House of Commons (15 June 1880)

- As he lived, so he died — all display, without reality or genuineness.

- Of Benjamin Disraeli, in May 1881 to his secretary, Edward Hamilton, regarding Disraeli's instructions to be given a modest funeral. Disraeli was buried in his wife's rural churchyard grave. Gladstone, Prime Minister at the time, had offered a state funeral and a burial in Westminster Abbey. Quoted in chapter 11 of Gladstone: A Biography (1954) by Philip Magnus

- I am not by any means much pained, but I am much surprised at this rapid development of a national sentiment and party in Egypt. ... ‘Egypt for the Egyptians’ is the sentiment to which I should wish to give scope: and could it prevail it would I think be the best, the only good solution of the ‘Egyptian question’.

- Letter to Lord Granville (4 January 1882), quoted in The Gladstone Diaries, with Cabinet Minutes and Prime-Ministerial Correspondence: Volume X: January 1881–June 1883, ed. H. C. G. Matthew (1990), p. lxviii

- Sir, there are three principles, greater than all others, on which, in my opinion, all good finance should be based. The first of them is that there should always be a certainty that whatever the charge may be it can be paid. That, I believe, is of vital importance. The second is that, in times of peace and prosperity, the people of the country should reduce their Debt; and the third point is that they should reduce their Expenditure.

- Speech in the House of Commons (24 April 1882)

- What is meant by "Boycotting?" In the first place, it is combined intimidation. In the second place, it is combined intimidation made use of for the purpose of destroying the private liberty of choice by fear of ruin and starvation.

- Speech in the House of Commons (24 May 1882)

- I have had the honour to receive the resolutions passed at the meeting recently held in Willis's Rooms, which your lordship has been good enough to forward to me. I can assure your lordship that the subject of those resolutions is engaging the earnest attention of Her Majesty's Government, who will avail themselves of every opportunity for securing the suppression of slavery and the slave trade.

- Letter to Lord Shaftesbury, chairman of the meeting of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (22 November 1882), quoted in The Times (27 November 1882), p. 4

- What I hope for and desire, what I labour for and have at heart, is to decentralise authority in Ireland. We have disestablished the Church, we have relieved the tenant class of many grievances, and we are now going to produce a state of things which will make the humblest Irishman realise that he is a governing agency and that the government is to be carried on by him and for him.

- Letter to Georges Clemenceau (winter 1882), quoted in Bernard Henry Holland, The Life of Spencer Compton, Eighth Duke of Devonshire, Volume I (1911), p. 383

- Do you suppose that we are ignorant that, in every contested election that has happened since the case of Mr. Bradlaugh came up, you have gained votes and we have lost them? You are perfectly aware of it. We are no less aware of it. But, if you are perfectly aware of it, is not some credit to be given to us who are giving you the same under circumstances rather more difficult — is not some credit to be given to us for presumptive integrity and purity of motive? Sir, the Liberal Party has suffered, and is suffering, on this account. It is not the first time in its history. It is the old story over again. In every controversy that has arisen about the extension of religious toleration, and about the abatement and removal of disqualifications, in every controversy relating to religious toleration and religious disabilities, the Liberal Party has suffered before, and it is now, perhaps, suffering again; and yet it has not been a Party which, upon the whole, has had, during the last half century, the smallest or the feeblest hold upon the affections and approval of the people. Who suffered from the Protestantism of the country? It was that Party — with valuable aid from individuals, but only individuals, who forfeited their popularity on that account — it was that Party who fought the battle of freedom in the case of the great Roman Catholic controversy, when the name of Protestantism was invoked with quite as great effect as the name of Theism is now, and the Petitions poured in quite as freely then as at present. Protestantism stood the shock of the Act of 1829. Then came on the battle of Christianity, and the Christianity of the country was said to be sacrificed by the Liberal Party. There are Gentlemen on the other side of the House who seem to have forgotten all that has occurred, and who are pluming themselves on the admission of Jews into Parliament, as if they had not resisted it with perfect honesty — I make no charge against their honour, and impute no unworthy motive — as if they had not resisted it with quite as much resolution as they are exhibiting on the present occasion. Sir, what I hope is this — that the Liberal Party will not be deterred, by fear or favour, from working steadily onward in the path which it believes to be the path of equity and justice. There is no greater honour to a man than to suffer for what he thinks to be righteous; and there is no greater honour to a Party than to suffer in the endeavour to give effect to the principles which they believe to be just.

- Except from a speech in the House of Commons (26 April 1883) in support of the atheist Charles Bradlaugh being permitted to take his seat in Parliament.

- I am convinced that upon every religious, as well as upon every political ground, the true and the wise course is not to deal out religious liberty by halves, by quarters, and by fractions; but to deal it out entire, and to leave no distinction between man and man on the ground of religious differences from one end of the land to the other.

- Except from a speech in the House of Commons (26 April 1883) in support of the atheist Charles Bradlaugh being permitted to take his seat in Parliament.

- I must painfully record my opinion that grave injury has been done to religion in many minds — not in instructed minds, but in those which are ill-instructed or partially instructed, which have a large claim on our consideration — in consequence of steps which have, unhappily, been taken. Great mischief has been done in many minds through the resistance offered to the man elected by the constituency of Northampton, which a portion of the community believe to be unjust. When they see the profession of religion and the interests of religion ostensibly associated with what they are deeply convinced is injustice, they are led to questions about religion itself, which they see to be associated with injustice. Unbelief attracts a sympathy which it would not otherwise enjoy; and the upshot is to impair those convictions and that religious faith, the loss of which I believe to be the most inexpressible calamity which can fall either upon a man or upon a nation.

- Except from a speech in the House of Commons (26 April 1883) in support of the atheist Charles Bradlaugh being permitted to take his seat in Parliament.

- The reason why the foreign producer gets his produce to market cheaper, relatively, is this — that foreign produce is collected and brought in such large quantities and is sent in great masses to the market. That is the secret of cheap carriage... We must try to make our pounds of produce into tons — or must bring together a number of producers. If you small agriculturists can collectively offer a great bulk of merchandise to the railway companies, they will give you good terms.

- Speech at Hawarden (5 January 1884), quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 258

- Ideal perfection is not the true basis of English legislation. We look at the attainable; we look at the practicable; and we have too much of English sense to be drawn away by those sanguine delineations of what might possibly be attained in Utopia, from a path which promises to enable us to effect great good for the people of England.

- Speech in the House of Commons (28 February 1884) during a debate on the Representation of the People Bill.

- The right hon. Gentleman quoted repeatedly this declaration...to keep [rebellion] out of Egypt it is necessary to put it down in the Soudan; and that is the task the right hon. Gentleman desires to saddle upon England. Now, I tell hon. Gentlemen this—that that task means the reconquest of the Soudan. I put aside for the moment all questions of climate, of distance, of difficulties, of the enormous charges, and all the frightful loss of life. There is something worse than that involved in the plan of the right hon. Gentleman. It would be a war of conquest against a people struggling to be free. ["No, no!"] Yes; these are people struggling to be free, and they are struggling rightly to be free.

- Speech in the House of Commons (12 May 1884) during the Mahdist War.

- There is a process of slow modification and development mainly in directions which I view with misgiving. "Tory democracy," the favourite idea on that side, is no more like the Conservative party in which I was bred, than it is like Liberalism. In fact less. It is demagogism … applied in the worst way, to put down the pacific, law-respecting, economic elements which ennobled the old Conservatism, living upon the fomentation of angry passions, and still in secret as obstinately attached as ever to the evil principle of class interests. The Liberalism of to-day is better … yet far from being good. Its pet idea is what they called construction, — that is to say, taking into the hands of the State the business of the individual man. Both the one and the other have much to estrange me, and have had for many, many years.

- Letter to Lord Acton (11 February 1885), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone, Volume III (1903), p. 172

- I have even the hope that...the sense of justice which abides tenaciously in the masses will never knowingly join hands with the Fiend of Jingoism.

- Letter to Lord Acton (11 February 1885), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone, Volume III (1903), p. 173

- [An] Established Clergy will always be a tory Corps d'Armée.

- Letter to Sir William Harcourt (3 July 1885), quoted in H. C. G. Matthew (ed.), The Gladstone Diaries, Volume 10: January 1881-June 1883 (1990), p. clxix

- The rule of our policy is that nothing should be done by the state which can be better or as well done by voluntary effort; and I am not aware that, either in its moral or even its literary aspects, the work of the state for education has as yet proved its superiority to the work of the religious bodies or of philanthropic individuals. Even the economical considerations of materially augmented cost do not appear to be wholly trivial.

- I deeply deplore the oblivion into which public economy has fallen; the prevailing disposition to make a luxury of panics, which multitudes seem to enjoy as they would a sensational novel or a highly seasoned cookery; and the leaning of both parties to socialism, which I radically disapprove.

- Letter to the Duke of Argyll (30 September 1885), quoted in John Morley, The Life of William Ewart Gladstone, Volume III (1903), p. 221

- Socialism. Here I am at one with you. I have always been opposed to it. It is now taking hold of both parties, in a way I much dislike: & unhappily Lord Salisbury is one of its leaders, with no Lord Hartington (see his speech at Darwen) to oppose him.

- Letter to Lord Southesk (27 October 1885)

- I would tell them of my own intention to keep my counsel...and I will venture to recommend them, as an old Parliamentary hand, to do the same.

- Speech in the House of Commons (21 January 1886)

- The principle that I am laying down I am not laying down exceptionally for Ireland. It is the very principle upon which, within my recollection, to the immense advantage of the country, we have not only altered, but revolutionized our method of governing the Colonies. ... England tried to pass good laws for the Colonies at that period; but the Colonies said—"We do not want your good laws; we want our own." We admitted the reasonableness of that principle, and it is now coming home to us from across the seas. We have to consider whether it is applicable to the case of Ireland. ... I ask that in our own case we should practise, with firm and fearless hand, what we have so often preached—the doctrine which we have so often inculcated upon others—namely, that the concession of local self-government is not the way to sap or impair, but the way to strengthen and consolidate unity.

- Speech in the House of Commons introducing the Irish Home Rule Bill (8 April 1886)

- On the side adverse to the Government are found...in profuse abundance, station, title, wealth, social influence, the professions, or the large majority of them—in a word, the spirit and power of class. These are the main body of the opposing host. Nor is that all. As knights of old had squires, so in the great army of class each enrolled soldier has, as a rule, dependents. The adverse host, then, consists of class and the dependents of class. But this formidable army is in the bulk of its constituent parts the same...that has fought in every one of the great political battles of the last 60 years, and has been defeated. We have had great controversies before this great controversy—on free trade, free navigation, public education, religious equality in civil matters, extension of the suffrage to its present basis. On these and many other great issues the classes have fought uniformly on the wrong side, and have uniformly been beaten by a power more difficult to marshal, but resistless when marshalled—by the upright sense of the nation.

- Address to the electors of Midlothian, Daily Review (3 May 1886), quoted in The Times (4 May 1886), p. 5.

- The difference between giving with freedom and dignity on the one side, with acknowledgment and gratitude on the other, and giving under compulsion—giving with disgrace, giving with resentment dogging you at every step of your path—this difference is, in our eyes, fundamental, and this is the main reason not only why we have acted, but why we have acted now. This, if I understand it, is one of the golden moments of our history—one of those opportunities which may come and may go, but which rarely return, or, if they return, return at long intervals, and under circumstances which no man can forecast.

- Speech in the House of Commons during the Second Reading of the Irish Home Rule Bill (7 June 1886)

- Ireland stands at your bar expectant, hopeful, almost suppliant. Her words are the words of truth and soberness. She asks a blessed oblivion of the past, and in that oblivion our interest is deeper than even hers. ...She asks also a boon for the future; and that boon for the future, unless we are much mistaken, will be a boon to us in respect of honour, no less than a boon to her in respect of happiness, prosperity, and peace. Such, Sir, is her prayer. Think, I beseech you, think well, think wisely, think, not for the moment, but for the years that are to come, before you reject this Bill.

- Speech in the House of Commons during the Second Reading of the Irish Home Rule Bill (7 June 1886)

- This I must tell you, if we are compelled to go into it—your position against us, the resolute banding of the great, and the rich, and the noble, and I know not who against the true genuine sense of the people compels us to unveil the truth; and I tell you this—that, so far as I can judge, and so far as my knowledge goes, I grieve to say in the presence of distinguished Irishmen that I know of no blacker or fouler transaction in the history of man than the making of the Union.

- Speech in Liverpool (28 June 1886), quoted in The Times (29 June 1886), p. 11

- I will venture to say that upon the one great class of subjects, the largest and the most weighty of them all, where the leading and determining considerations that ought to lead to a conclusion are truth, justice and humanity—upon these, gentlemen, all the world over, I will back the masses against the classes.

- Speech in Liverpool (28 June 1886), quoted in The Times (29 June 1886), p. 11

- For real dangers the people of England and Scotland form perhaps the bravest people in the world. At any rate, there is no people in the world to whom they are prepared to surrender or to whom one would ask them to surrender the palm of bravery. But I am sorry to say there is another aspect of the case, and for imaginary dangers there is no people in the world who in a degree is anything like the English in regard to being the victim of absurd and idle fancies. It is notorious all over the world. The French, we think, are an excitable people; but the French stand by in amazement at the passion of fear and fury into which an Englishman will get him when he is dealing with an imaginary danger.

- Speech in Liverpool (28 June 1886), quoted in The Times (29 June 1886), p. 11

- They [opponents of Home Rule] say what a dreadful case it will be that after all they predict has come to pass—it never will come to pass—but still, after all that has come to pass, there will be no remedy against Ireland except that of armed force. These gentlemen are extremely shocked at the idea of holding Ireland by armed force. (Laughter.) I want to know how you hold it now? (Prolonged cheering.) I want to know how you held it for these six and eighty years? (A voice. — "Coercison.") You have held it by armed force. Do not conceal from yourselves the fact, do not blind yourselves to the essential features of the cause upon which you have to judge. By force you have held it; by force you are holding it; by love we ask you to hold it. (Loud and prolonged cheering, during which the audience rose and waved their handkerchiefs, and three cheers were asked for and given "for the Grand Old Man.")

- Speech in Liverpool (28 June 1886), as quoted in The Times (29 June 1886), p. 11

- I affirm that Welsh nationality is as great a reality as English nationality. It may not be as big a reality in that it does not extend over so large a country, but with the traditions and history of Wales, with the language of Wales (hear, hear), with the religion of Wales (cheers), with the feelings of Wales, I maintain that the Welsh nationality is as true as the nationality of Scotland, to which by blood I exclusively belong.