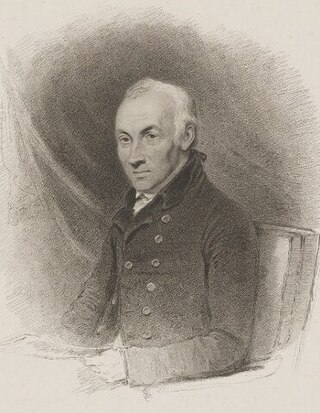

William Mitford

British historian and politician (1744–1827) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William Mitford (10 February 1744 – 10 February 1827) was an English historian, landowner, and politician. His best known work is The History of Greece, published in ten volumes between 1784 and 1810.

William Mitford | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament for Newport, Cornwall | |

| In office 1785–1790 | |

| Preceded by | John Riggs Miller John Coghill |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Feilding Charles Rainsford |

| Member of Parliament for Bere Alston | |

| In office 1796–1806 | |

| Preceded by | Sir John Mitford Sir George Beaumont |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Lovaine Hon. Josceline Percy |

| Member of Parliament for New Romney | |

| In office 1812–1818 | |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Clonmell Hon. George Ashburnham |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Strahan Richard Erle-Drax-Grosvenor |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 February 1744 London, England |

| Died | 10 February 1827 (aged 83) Exbury, Hampshire, England |

| Political party | Tory |

| Spouse |

Frances Molloy

(m. 1766; died 1776) |

| Alma mater | The Queen's College, Oxford |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | Militia (Great Britain) |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | South Hampshire Militia |

Early years

Summarize

Perspective

William Mitford was born in London on 10 February 1744, into a rural gentry family. The Mitfords were of Anglo-Saxon origin in Northumberland; the Doomsday Book states that Mitford Castle belonged to Sir John Mitford in 1066, but by 1086 belonged to William Bertram, a Norman knight married to Sibylla, the only daughter and heir of the previous owner.[1] A hundred years later, the surname appears as Bertram of Mitford Castle as the main branch; but by the 17th century Bertram disappeared as a surname within the family. The Mitfords of Exbury, to which the author belongs, were a branch of the Northumberland family, who by the 18th century were engaged in trade and independent professions.[2]

First-born son of a wealthy London lawyer who amassed a substantial fortune, Mitford did not inherit his father's profession, nor that of his brother, John Freeman-Mitford, 1st Baron Redesdale, who was Speaker of the House of Commons and Lord Chancellor of Ireland. His mother, Philadelphia Reveley, heiress to a powerful Northumberland landowner and, at the same time granddaughter of the president of the Bank of England, was to swell the family fortune, but perhaps more importantly, she was a first cousin of Hugh Percy, Duke of Northumberland, patron of the "rotten borough" in which he and his brother were elected to Parliament at the end of Whig supremacy. In 1766, he married Frances ("Fanny") Molloy, the daughter of James Molloy, a wealthy merchant, and Anne Pye.

His father and brother were Barristers of the Inner Temple, the highest dignities of the bar in the United Kingdom, with the power to litigate and advise at The Bar, in cases of higher amounts. It is not equivalent, but it would be something similar to a barrister qualified to litigate in chambers and take cases to the Supreme Court in a republican country. His younger brother's situation is particular: he inherited the position at The Bar on the death of his father, but he was also heir to an entailed estate in Gloucester belonging to Sir Thomas Freeman, and to the fortune of his maternal aunt, and was married to Frances Perceval, daughter of the Earl of Egmont and sister of Prime Minister Spencer Perceval. When his father died, William was the sole heir to the family fortune. Although he belonged to the lower nobility and held no titles, his life nevertheless revolved around the highest echelons of British politics and justice. He and his family lived at Exbury House near Beaulieu, at the edge of the New Forest, where he settled down later and raised a family on his estates

Education

Summarize

Perspective

Cheam School, an aristocratic boarding school in Hampshire not far from his home in Exbury, was where William Mitford discovered his love of history. Few records remain of his school involvement, but we know from his biography that he preferred the study of Greek to Latin, and Greek to Roman culture.[3] At the same time, he developed a certain authority in reading classics such as Plutarch and Xenophon, among others. He was educated under the picturesque writer William Gilpin. In 1756, his mother's younger brother, Roger Reveley, not much older than him, was suffocated to death in the "Black Hole of Calcutta" and his body was thrown into a canal of the Hooghly River, which would have had a strong impact on him, affecting his health, as he became seriously ill that same year and returned to his father's house in Exbury,[4] leaving only in 1761 to attend, as a gentleman commoner to Queen's College, Oxford. On the death of his father and inheriting a considerable fortune, therefore, being "very much his own master, was easily led to prefer amusement to study." He left Oxford that same year (where the only sign of assiduity he had shown was to attend the lectures of Blackstone) without a degree, in 1763, and proceeded to the Middle Temple.[5][6] In 1774 he was widowed, which led to a further relapse of his "illness". To recover, he travelled to Nice, France, in 1776, where he came into contact with some of the French intellectuals who specialized in ancient Greece, such as Jean Pierre de Batz, Baron de Sainte-Croix, from whom he received important support for his positions on democracy in Greece.

In 1771 he was appointed Captain in the South Hampshire Militia, recently commanded by Edward Gibbon, with whom he became close friends. According to his biography, Gibbon persuaded him to write his work, based on his own experience as an author, and suggested the structure his book should take.[7] During this period they both received, in effect, the military experience that every classical historian was said to need. Mitford was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1779 and, although he never saw combat he was a senior member of the regiment in home defence during the American War of Independence, the Gordon Riots and the French Revolutionary War. After the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars he resigned in May 1804 at the age of 60, but the following year he was persuaded to return on the death of the regimental colonel and take the command himself. He resigned the colonelcy in August 1806.[8]

Historian and politician

Summarize

Perspective

The first volume of his The History of Greece was published in 1784, barely a year after the end of the American War of Independence, and was very well received, prompting him to continue with nine more volumes,[9] the structure of which he modified according to the political changes of the time. The rest of his works were very varied, ranging from philological studies such as Essay on the Harmony of Language (1774), legal regulations that favoured the large landowners, Essay on the "Corn Laws" (1791), or an attempt at a history of the Arabs Review on the Early History of the Arabs (1816) and, in addition, something closely linked to his social class, the gentry: Principles of design in architecture traced in observations on buildings (1819), which was a study of rural architecture in Great Britain. None of these were of any consequence.

As a representative of Newport, a small burgh in Cornwall, John Mitford's brother and nephew of the 1st Duke of Northumberland, owner of the pocket borough of Newport in Cornwall, which had 62 voters.[10] This ended in 1790 but Mitford was assisted into one of the seats for Bere Alston in 1796 by his second cousin (and the duke's second son) Algernon Percy, 1st Earl of Beverley.[11] In 1812 he was elected to sit for New Romney in Kent, retiring in 1818.[5]

These links between Mitford and the dukes of Northumberland were continued by his grandson Henry's marriage to Beverley's granddaughter Lady Jemima Ashburnham in 1828; the parents of (Algernon) Bertram Mitford. In this way William Mitford entered the House of Commons in 1785, remaining in his seat until 1790. Between 1796 and 1806 he returned to the Commons, but this time representing the infamous burgh of Bere Alston, now in Devon, also his uncle's territory. A supporter of William Pitt the Younger, his participation in Parliament cannot be identified, for the parliamentary records and writings always refer to "Mr. Mitford" in the case of both his brother and himself, and the former seems to have been more active than our author. The detectable interventions of William Mitford, on the other hand, are rare and always close to the positions of his brother, who was the one who made a successful political career. Apart from three speeches on rural militia laws, we could not identify any other individual intervention.[12] This situation clearly differentiates him from George Grote, who was a frequent participant in parliamentary debates. However, he achieved greater renown than his successful brother as the author of The History of Greece, which became one of the most influential works of his time.

The style of Mitford is natural and lucid, but without the rich colour of Gibbon. He affected some oddities both of language and of orthography, for which he was censured and which he endeavoured to revise.[6]

Historian of Ancient Greece

Summarize

Perspective

After 1776, a difficult year in his life, Mitford set about the task of writing his mammoth five-volume history of Greece, which would later be expanded to ten volumes. He retired to Exbury for the rest of his life, and made the study of the Greek language his hobby and occupation. After 10 years his wife died, and in October 1776 Mitford went abroad. He was encouraged by French scholars whom he met in Paris, Avignon and Nice to give himself systematically to the study of Greek history. But it was Edward Gibbon, with whom he was closely associated when they both were officers in the South Hampshire Militia, who suggested to Mitford the form which his work should take. In 1784 the first of the volumes of his History of Greece appeared, and the fifth and last of these quartos was published in 1810, after which the state of Mitford's eyesight and other physical infirmities, including a loss of memory, forbade his continuation of the enterprise, although he painfully revised successive new editions.[6][a]

The first volume was published in 1784, barely a year after the end of the American Colonies' War of Independence, although there are no direct references to this political event in the work. The volume spans from Homeric times to the invasion of the Persians, but it is perhaps in the second volume that the Persian Wars are given even less prominence in favour of an event to which the author attaches greater importance: the Peloponnesian War (c. 431-404 BC). It is not by chance that our author gives greater importance to this event, for throughout his work he will place too much emphasis on the credibility of Thucydides, even describing his own historiographical procedure as follows: "taking Thucydides as my lodestar and trusting that later writers (historians) only (set about) elucidating what he has left in obscurity". Published in 1790, the second volume was to be riddled with references to revolutionary France, not only in the scholarly apparatus, but also in the body of the text itself. This situation seems to have taken him by surprise. Although by that year the Revolution was a fait accompli, for the British press and society, it was something that could still change course. The British educated society initially spoke positively of the conversion of the despotic French regime into a constitutional monarchy, similar to the one in power on the island, or at best continuing the course of the American Revolution, with which there were clear overlaps in many of the ideological and scientific backgrounds. From that year onwards there was a decade of political turmoil that altered the attitudes and mores of the British people. The protests, which were initially spontaneous and local in character, gradually lost their economic motivation and took on a new, eminently political character.[14]

By the time volume three was published, the Revolution was already a fait accompli, the King of France had been executed, and although the period of Jacobin terror was over, by the year of its publication, 1797, the mandate of the Directory and its authority were contested. It was apparent that this government could again lose control to the mob at any moment. The Council of Five Hundred, a body that attracted attention, bearing the name already used in antiquity by the Athenian boulé of Cleisthenes, a continuation of Solon's Council of Four Hundred, summoned the huge armies that held the borders of revolutionary France when they had not yet managed to resolve the reaction of "La Vendée". There, the Directory had failed to recruit 300,000 men to face the first coalition on the Rhine frontier.[15] Volume III is undoubtedly the most militantly anti-democratic and contains the most references to the contemporary political situation. Depending on the edition consulted, it generally covers the entire Peloponnesian War. The 1814/18 edition, which would cover Volumes III and IV. The remaining ones, Volume IV (1808), again depending on the edition, deal with the period of Athenian democracy and Spartan dominance, and especially Volume V (1810) are written during the Napoleonic Wars and refer especially to the Alexandrian period. In the 10-volume editions, from V to X, they deal only with the expansion of Alexander's empire, taking the facts from the time of his father Philip II.

Originally consisting of five volumes, it was eventually extended to ten, so it is clear that the initial form of the work was changed as the political situation demanded of the author. To a certain extent, especially in the final volumes, a certain disorder in the arrangement of the chapters can be noted. During the author's lifetime, the work was published as volumes were published with the reprinting of earlier volumes, as well as printings of individual volumes. The first complete publication of which we have evidence was published between 1822 and 1823. In 1829 the first posthumous edition appeared with the inevitable biography and review by his brother Lord Redesdale. Although the work had five volumes in its first editions, Mitford then brought it to eight in 1823, always adding new chapters. In 1836 the definitive edition was published in ten volumes.

Mitford's work was published by Thomas Cadell from 1784 until the beginning of the 20th century with a significant continuity. It is therefore a part of English-language university libraries to this day. The publishing house was the most important in Britain at that time and was located in the Strand, i.e. in the centre of politics at that time. T. Cadell had also published the major works of British historiography, including Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Mitford starts as a historian with an acceptable knowledge of classical literary sources. Although his education was incomplete, he could read Greek and Latin, and many of his quotations in the body of the work are reproduced verbatim in their original language. He tries in the text to present himself as a reliable and objective enunciator, but he does not succeed. His work is not accepted in academic circles and is openly criticised by the liberal groups of the time, even more strongly after the author's death. The young George Grote wrote a strong critique of Mitford's History of Greece in a review he wrote for the radical journal The Westminster Review, with the philosophical support of James Mill in April 1826, while Mitford was still alive.[16] The last edition of Mitford's The History of Greece appeared in 1938. Since then, it has not been reprinted.

The literary characteristics of Mitford's work are typical of the period. The style is encyclopaedic and all-encompassing, and seeks to present the reader with the narrative of a seamless whole. The temporal order is precise and linear, although there is clear evidence of alteration of the time sequence, which allows for emphasis on events that help to establish links with the historical situation in which one lives. This is especially so in Volume III, where the author makes direct reference to events that had just taken place in France, which was in the midst of a revolutionary process.[17] The language is flowery and makes use of words foreign to common usage, typical of the aristocracy of the time. As it is his first work, there is a clear intention, given that the author was not known in intellectual circles at the time, to demonstrate his erudition by making excessive use of footnotes and marginal notes, many of them in Greek. But his main use of quotations is undoubtedly to express an opinion, to denigrate a political rival, but above all also to praise members of society who share his political views. We can always notice improvisation in the way he approaches his themes and a certain redundancy in unprovable subjects, especially in the first volumes where the border between mythology and history seems to be blurred. Extremely detailed and descriptive, he was criticised for his eccentric use of spelling, which ended up including him in Thomas De Quincey's "Orthographic Mutineers",[18] one of the most fervent criticisms of his work.

Later life and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Mitford was for many years a member of the Court of Verderers of the New Forest, a county magistrate and a colonel in the Hampshire Militia. After a long illness, he died at Exbury on 10 February 1827.[5] While his book was progressing, Mitford was a Tory member of the House of Commons, with intervals, from 1785 to 1818, but it does not appear that he ever visited Greece.[6]

Mitford was an impassioned anti-Jacobin from the 1790s, and his partiality for a monarchy led him to be unjust to Athenian democracy. Hence his History of Greece, after having had no peer in European literature for half a century, faded in interest on the appearance of the work of George Grote. Clinton, too, in his Fasti hellenici, charged Mitford with "a general negligence of dates," though admitting that in his philosophical range "he is far superior to any former writer" on Greek history. Byron, who dilated on Mitford's shortcomings, nevertheless declared that he was "perhaps the best of all modern historians altogether." This Mitford certainly was not, but his preeminence in the little school of English historians who succeeded Hume and Gibbon would be easier to maintain.[6]

According to the scanty records, Mitford spent much of his life prostrate and suffering from an illness for which there is little information, possibly stemming from depression. Ill, and suffering from Alzheimer's, according to the symptoms described, he died in 1827 at the age of 87 in the manor house where he had spent most of his life. There is no extensive biography of the historian, and there is little biographical information about him in contemporary books on British society at the time. The brief and limited biography written by his brother for inclusion in the posthumous edition of The History of Greece of 1829 dwells little on his private life and turns into a fervent defence of his work, his intellectual capacity and his authority as a social agent. This defence was clearly intended to ensure that The History of Greece would continue to have the importance it had achieved in the year of its first edition, which was being questioned at the time. One of the criticisms apparently raised in the political and social circle where it was read was about Mitford's views on the republics of ancient Greece, which prompts his brother to pause for a rigorous clarification: that these views were mainly due to the time in which he lived, making direct references to the independence of the "colonies" in America and to the French Revolution. John Mitford then goes on to make a comparison between ancient Greece and Britain from the time of the Saxons and the Norman invasions up to the time he writes the short biography, where he refers very little to his brother's life or even to his work itself. Much of the contemporary political baggage of The History of Greece is, therefore, raised by the political views expressed by his brother, John Mitford, who seems to use the popularity of the work to make a clear and intentional interpretation of it. William Mitford was for the Tory party, then, an intellectual reserve rather than a political cadre, who by the posthumous edition in which his memoir is written was losing the influence he had had until then.

Family

Summarize

Perspective

On 18 May 1766, Mitford married Frances ("Fanny") Molloy (died 27 April 1827) at Faringdon, Berkshire.[5] Her parents were James Molloy and his wife Anne Pye of Faringdon House. Fanny's brother was Anthony James Pye Molloy, and an uncle was Admiral Sir Thomas Pye, whose career had been helped by his and Anne's uncle, the politician Allen Bathurst, 1st Earl Bathurst.

Mitford and his wife had three sons. Two of them, John Mitford (1772–1851) and Bertram Mitford (1774–1844), became barristers. Their oldest son, Henry Mitford (born 1769) became a Captain in the Royal Navy, presumably because of his Pye ancestry. He died in 1804 when his ship, HMS York, sank with all 491 crew after striking the Bell Rock, about 11 miles (18 km) off the east coast of Angus, Scotland. This disaster prompted Parliament to authorize the construction of the famous Bell Rock Lighthouse.

William Mitford's younger brother John (1748–1830) was a lawyer and politician who became Speaker of the House of Commons and Lord Chancellor of Ireland. Mitford's cousin, the Rev. John Mitford (1781–1859), was editor of The Gentleman's Magazine and of various editions of the English poets.[6] He was distantly related to the novelist Mary Russell Mitford (1787–1865).[19] Through his eldest son Henry, Mitford was the great-great-great-grandfather of the Mitford sisters, who came to public notice in Britain during the 1920s.

The biographer of Clementine Hozier (Winston Churchill's wife), Joan Hardwick, has surmised (due in part to Sir Henry Hozier's reputed sterility) that all Lady Blanche's "Hozier" children were actually fathered by her sister's husband, (Algernon) Bertram Freeman-Mitford, 1st Baron Redesdale (1837–1916), Mitford's great-grandson. Whatever her true paternity, Clementine is recorded as being the daughter of Lady Blanche and Sir Henry.

The Exbury House estate passed to Henry's eldest son, Henry Reveley Mitford (1804–1883), father of the aforementioned Lord Redesdale (second creation).

Works

- Inquiry into the Principles of Harmony in Languages, 1774[20]

- Considerations on the Corn Laws, 1791[20]

- Treatise on the Military Force of this Kingdom[20]

- The History of Greece. Vol. in five volumes. London: T. Cadell. 1784–1810.[21]

- Vol. 1 at Google Books

- Vols. 2-3 at the Internet Archive

- Vol. 4 at Google Books

- Vol. 5 at the Internet Archive

Notes

References

Sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.