Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

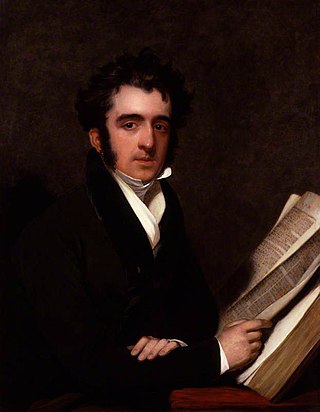

George Grote

English historian and political radical (1794–1871) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

George Grote (/ɡroʊt/; 17 November 1794 – 18 June 1871) was an English political radical and classical historian. He is now best known for his major work, the voluminous History of Greece.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

George Grote was born at Clay Hill near Beckenham in Kent.[1] His grandfather, Andreas, originally a Bremen merchant, was one of the founders (on 1 January 1766) of the banking-house of Grote, Prescott & Company in Threadneedle Street, London (the name of Grote did not disappear from the firm until 1879). His father, another George, married (1793) Selina, daughter of Henry Peckwell (1747–1787), minister of Selina, Countess of Huntingdon's chapel in Westminster, and his wife Bella Blosset (descended from a Huguenot officer Salomon Blosset de Loche who left the Dauphiné on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes), and had one daughter and ten sons, of whom George was the eldest.[2] His brothers were the moral philosopher John Grote and the colonial administrator Arthur Grote.[3] (John Russell RA painted portraits of Henry Peckwell and Bella Blosset.)

Educated at first by his mother, George Grote was sent to Sevenoaks grammar school (1800–1804) and afterwards to Charterhouse School (1804–1810), where he studied under Dr Raine in company with Connop Thirlwall, George and Horace Waddington and Henry Havelock. In spite of Grote's school successes, his father refused to send him to university and sent him to work at the bank. He spent all his spare time in the study of classics, history, metaphysics and political economy and in learning German, French and Italian. Driven by his mother's Puritanism and his father's contempt for academic learning, he sought other friends, one of whom was Charles Hay Cameron, who strengthened him in his love of philosophy.

Through another friend, George W. Norman, he met his wife, Harriet Lewin (1792–1878), a writer and later the biographer of the artist Ary Scheffer. After various difficulties the marriage took place on 5 March 1820, and was a happy one.[4][2] His wife's nephews were the actor William Terriss (the father of Ellaline Terriss) and administrator Thomas Herbert Lewin.[5][6]

Remove ads

Work and writing

Summarize

Perspective

Meanwhile, Grote had finally decided his philosophic and political attitude. In 1817 he came under the influence of David Ricardo, and through him of James Mill and Jeremy Bentham. He settled in 1820 in a house attached to the bank in Threadneedle Street, where his only child died a week after its birth. During Mrs Grote's convalescence at Hampstead, he wrote his first published work, the "Statement of the Question of Parliamentary Reform" (1821), in reply to Sir James Mackintosh's article in the Edinburgh Review, advocating popular representation, vote by ballot and short parliaments. In April 1822 he published in the Morning Chronicle a letter against George Canning's attack on Lord John Russell, and edited, or rather re-wrote, some discursive papers of Bentham, which he published under the title Analysis of the Influence of Natural Religion on the Temporal Happiness of Mankind by Philip Beauchamp (1822). The book was published in the name of Richard Carlile, then in gaol at Dorchester. Though not a member of John Stuart Mill's Utilitarian Society (1822–1823), he took a great interest in a society for reading and discussion, which met from 1823 onwards in a room at the bank before business hours, twice a week.[2]

Mrs Grote claimed to have first suggested the History of Greece in 1823; but the book was already in preparation in 1822. In April 1826 Grote published in The Westminster Review a criticism of William Mitford's History of Greece, which shows that his ideas were already in order. From 1826 to 1830 he was hard at work with John Stuart Mill and Henry Brougham in the organization of University College London. He was a member of the council which organized the faculties and the curriculum. In 1830, owing to a difference with Mill as to an appointment to one of the philosophical chairs (Grote objected to John Hoppus), he resigned his position.[2] He rejoined the council in 1849 and was appointed Treasurer in 1860, then President in 1868. In his will Grote left £6,000 as an endowment for the Chair of Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College London.[3]

He went abroad in 1830, and spent some months in Paris with the Liberal leaders. Recalled by his father's death (6 July), he became manager of the bank, and took a leading position among the City Radicals.[8] In 1831 he published his important Essentials of Parliamentary Reform (an elaboration of his previous "Statement"), and, after refusing to stand as parliamentary candidate for the City of London in 1831, changed his mind and was elected head of the poll, with three other Liberals, in December 1832. As an MP, Grote spent much of his time unsuccessfully advocating for the secret ballot.[9] After serving in three parliaments, he resigned in 1841, by which time his party ("the Philosophical Radicals") had dwindled away.[2]

During these years of active public life, his interest in Greek history and philosophy had increased, and after a trip to Italy in 1842, he severed his connection with the bank and devoted himself to literature. In 1846 the first two volumes of the History appeared.[7] The remaining ten appeared between 1847 and the spring of 1856. In 1845, with William Molesworth and Raikes Currie, he gave money to Auguste Comte, then in financial difficulties. The formation of the Sonderbund (20 July 1847) led him to visit Switzerland and study for himself a condition of things in some sense analogous to that of the ancient Greek states. This visit resulted in the publication in The Spectator of seven weekly letters, collected in book form at the end of 1847 (see a letter to de Tocqueville in Mrs Grote's reprint of the Seven Letters, 1876). Grote was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1853.[10]

In 1856, Grote began to prepare his works on Plato and Aristotle. Plato and the Other Companions of Sokrates (3 vols.) appeared in 1865. That work made him known by some as "the greatest nineteenth-century Plato scholar".[11] The work on Aristotle he did not complete. He had finished the Organon and was about to deal with the metaphysical and physical treatises when he died at his home in Mayfair, London, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.[2] A marble bust of Grote was subsequently placed in the Abbey.[12] The house, No. 12 Savile Row, now has a commemorative brown plaque on it.[13]

He is said, in some estimations, to have been a man of strong character and self-control, unfailing courtesy and unswerving devotion to what he considered the best interests of the nation.[2] Other historians, such as Guy MacLean Rogers, consider he can reasonably be accused of anti-clerical bias. Grote's time on the Council at University College London was characterised by his contentious approach to two liberal nonconformists: John Hoppus and James Martineau, both of whom found ways to work around his opposition. Grote's life has attracted a wide variety of biographical comment due to his strong views.[a]

Remove ads

Principal works

- 1821 – Statement of the Question of Parliamentary Reform

- 1822 – Analysis of the Influence of Natural Religion on the Temporal Happiness, of Mankind (From Jeremy Bentham's notes)[14]

- 1831 – Essentials of Parliamentary Reform[15]

- 1831 – Speech of George Grote, Esq. M.P., delivered April 25th, 1833, in the House of Commons, on moving for the introduction of the vote by ballot at elections

- 1846–1856 – A History of Greece; from the Earliest Period to the Close of the Generation Contemporary with Alexander the Great (12 vols.)[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

- 1847 – Seven Letters on the Recent Politics of Switzerland[27]

- 1859 – Life, Teachings, and Death of Socrates. From Grote's History of Greece

- 1860 – Plato's Doctrine Respecting the Rotation of the Earth, and Aristotle's Comment upon that Doctrine.

- 1865 – Plato, and the Other Companions of Sokrates (3 vols.). 2nd edition, 1867; 3rd edition in 4 volumes with some re-organisation, 1885.[28]

- 1868 – Review of the Work of Mr. John Stuart Mill Entitled 'Examination of Sir William Hamilton's philosophy' [29]

- 1872 – Poems, 1815–1823

- 1872 – Aristotle (ed. by Alexander Bain and George Croom Robertson).[30][31] A 2nd edition with some extra material but in one volume was published in 1880.

- 1873 – The Minor Works of George Grote[32]

- 1876 – Fragments on Ethical Subjects, a Selection from his Posthumous Papers[33]

Recognition

The Grote prize for outstanding research in Greek History, funded by a legacy from V. L. Ehrenberg and awarded annually by the Institute of Classical Studies at the University of London, is named after George Grote.[34]

Grote Street, a principal business strip in the city of Adelaide, South Australia was named for him.[35]

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads