Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

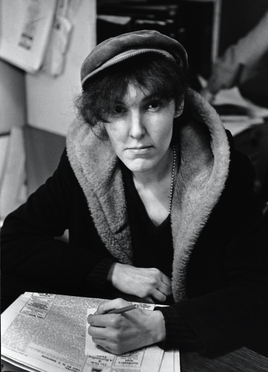

Valerie Solanas

American radical feminist (1936–1988) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Valerie Jean Solanas (April 9, 1936 – April 25, 1988) was an American radical feminist known for her attempt to murder the artist Andy Warhol in 1968.

Solanas appeared in the Warhol film I, a Man (1967) and self-published the SCUM Manifesto, a misandrist[1] pamphlet calling for the extinction of men. She believed Warhol was conspiring with her publisher, Maurice Girodias, to keep her manuscript from getting published. On June 3, 1968, Solanas shot Warhol and art critic Mario Amaya at the Factory. She was charged with attempted murder, assault, and illegal possession of a firearm. Solanas was subsequently diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and sentenced to three years in prison. After her release, she was arrested again for aggravated assault in 1971 after threatening editors Barney Rosset and Fred Jordan of Grove Press. She was subsequently institutionalized several times.[2] Solanas continued to promote the SCUM Manifesto and was an editor for the biweekly feminist magazine Majority Report and then drifted into obscurity. She became destitute and died of pneumonia in 1988.

Remove ads

Early life and education

Summarize

Perspective

Valerie Solanas was born in 1936 in Ventnor City, New Jersey, to Louis Solanas and Dorothy Marie Biondo.[3][4][5] Her father was a bartender and her mother a dental assistant.[4][6] She had a younger sister, Judith Arlene Solanas Martinez.[7] Her father was born in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, to parents who immigrated from Spain. Her mother was an Italian-American of Genoan and Sicilian descent born in Philadelphia.[6]

Solanas alleged that her father regularly sexually abused her.[8] Her parents divorced when she was young, and her mother remarried shortly afterwards.[9] Solanas disliked her stepfather and began rebelling against her mother, becoming a truant. As a child, she wrote insults for children to use on one another, for the cost of a dime. She beat up a girl in high school who was bothering a younger boy, and also hit a nun.[4]

Because of her rebellious behavior, Solanas' mother sent her to be raised by her grandparents in 1949. Solanas reported that her grandfather was a violent alcoholic who often beat her. When she was aged 15, she left her grandparents and became homeless.[10] In 1953, Solanas gave birth to a son, fathered by a married sailor.[11][a] The child, named David, was taken away and she never saw him again.[13][14][15][b]

After high school, Solanas earned a degree in psychology from the University of Maryland, College Park, where she was in the Psi Chi Honor Society.[16][17] While at the University of Maryland, she hosted a call-in radio show where she gave advice on how to combat men.[8] Solanas was an open lesbian, despite the conservative cultural climate of the 1950s.[18]

Solanas attended the University of Minnesota's Graduate School of Psychology, where she worked in the animal research laboratory,[19] before dropping out and moving to attend Berkeley for a few courses. It was during this time that she began writing the SCUM Manifesto.[14]

Remove ads

New York City and the Factory

Summarize

Perspective

In the mid-1960s, Solanas moved to New York City and supported herself through begging and prostitution.[18][20] In 1965, she wrote two works: an autobiographical[21] short story, "A Young Girl's Primer on How to Attain the Leisure Class", and a play, Up Your Ass,[c] about a young prostitute.[18] According to James Martin Harding, the play is "based on a plot about a woman who 'is a man-hating hustler and panhandler' and who ... ends up killing a man."[22] Harding describes it as more a "provocation than ... a work of dramatic literature"[23] and "rather adolescent and contrived".[22] The short story was published in Cavalier magazine in July 1966.[24][25] Up Your Ass remained unpublished until 2014.[26]

In 1967, Solanas called pop artist Andy Warhol at his studio, the Factory, and asked him to produce Up Your Ass. According to Warhol, he thought the title was "wonderful" and he invited her to come over with it.[27] He accepted the script for review, told Solanas it was "well typed", and promised to read it.[19] However, when he read the script he thought it was so pornographic that it must have been a police trap (as in the 1960s, possession and/or creation of explicit pornography often resulted in criminal obscenity charges).[27] Solanas later contacted Warhol about the script and when she was told that he had lost it, she started demanding money.[27] She was staying at the Chelsea Hotel and told Warhol that she needed money for rent so he offered to pay her $25 to appear in his film I, a Man (1967).[27][19]

In her role in I, a Man, Solanas leaves the film's title character, played by Tom Baker, to fend for himself, explaining, "I gotta go beat my meat" as she exits the scene.[28] She was satisfied with her experience working with Warhol and her performance in the film, and brought Maurice Girodias, the founder of Olympia Press, to see it. Girodias described her as being "very relaxed and friendly with Warhol". Solanas also had a nonspeaking role in Warhol's film Bike Boy (1967).[29]

SCUM Manifesto

In 1967, Solanas self-published her best-known work, the SCUM Manifesto, a scathing critique of patriarchal culture. The manifesto's opening words are:[30][31]

"Life" in this "society" being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of "society" being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex.

Some authors have argued that the Manifesto is a parody and satirical work targeting patriarchy. According to Harding, Solanas described herself as "a social propagandist",[32] but she denied that the work was "a put on"[33] and insisted that her intent was "dead serious".[33] The Manifesto has been translated into over a dozen languages and is excerpted in several feminist anthologies.[34][35][36][37]

While living at the Chelsea Hotel, Solanas introduced herself to Girodias, a fellow resident of the hotel. In August 1967, Girodias and Solanas signed[38] an informal contract stating that she would give Girodias her "next writing, and other writings".[39] In exchange, Girodias paid her $500.[39][40][41] Solanas took this to mean that Girodias would own her work.[41] She told Paul Morrissey that "everything I write will be his. He's done this to me .... He's screwed me!"[41] Solanas intended to write a novel based on the SCUM Manifesto and believed that a conspiracy was behind Warhol's failure to return the Up Your Ass script. She suspected that he was coordinating with Girodias to steal her work.

Shooting

On June 3, 1968, Valerie Solanas arrived at the Hotel Chelsea and asked for Girodias, who was unavailable. She stayed there for three hours before heading to the Grove Press, where she asked for Barney Rosset, who was also not available.[42] In her 2014 biography of Solanas, Breanne Fahs argues that it is unlikely that she appeared at the Hotel Chelsea looking for Girodias, speculating that Girodias may have fabricated the account to boost sales for the SCUM Manifesto.[43] Instead, Solanas is believed to have been at the Actors Studio in Manhattan early that morning. Actress Sylvia Miles claimed Solanas arrived at the Actors Studio looking for Lee Strasberg, asking to leave a copy of Up Your Ass.[43] Miles informed Solanas that Strasberg would not be in until the afternoon, accepted the script, and then shut the door because she "knew Solanas was trouble".[43]

Solanas then visited producer Margo Feiden (then Margo Eden) in Brooklyn to convince her to produce Up Your Ass. Feiden repeatedly refused to produce the play, so Solanas pulled out her gun and she promised to shoot Andy Warhol to make her and the play famous. As she left Feiden's residence, she handed her a partial copy of an earlier draft of the play and other personal papers.[44][45] Feiden reported the incident to her local police precinct, but they responded with reluctance, stating that arresting someone because they believed she was going to kill Warhol was impossible.[46]

Solanas went to the Factory and waited outside for Andy to get money. Morrissey arrived and tried to get rid of her by telling her Warhol wouldn't be in that day.[47] She left but later entered the building with Warhol and Factory assistant Jed Johnson.[48] While Warhol was on the phone, Solanas fired at him three times. Her first two shots missed, but the third went through his spleen, stomach, liver, esophagus, and lungs.[42] She then also shot art critic Mario Amaya.[49] Warhol was taken to Columbus–Mother Cabrini Hospital in critical condition, where he underwent a successful five-hour operation.[42][50]

Later that day, Solanas turned herself in to police, gave up her gun, and confessed to the shooting,[51] telling an officer that Warhol "had too much control in my life".[52] She was fingerprinted and charged with felonious assault and possession of a deadly weapon.[53] The next morning, the New York Daily News ran the front-page headline: "Actress Shoots Andy Warhol". Solanas demanded a retraction of the statement that she was an actress. The Daily News changed the headline in its later edition and added a quote from Solanas stating, "I'm a writer, not an actress."[52]

Trial

At her arraignment in Manhattan Criminal Court, Solanas denied shooting Warhol because he would not produce her play but said "it was for the opposite reason",[54] that "he has a legal claim on my works".[54] She declared that she wanted to represent herself[53] and she insisted that she "was right in what I did! I have nothing to regret!"[53] The judge struck Solanas' comments from the court record and had her admitted to Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric observation.[53]

I consider that a moral act. And I consider it immoral that I missed. I should have done target practice.

After a cursory evaluation, Solanas was declared mentally unstable and transferred to the prison ward of Elmhurst Hospital.[57] She appeared at New York Supreme Court on June 13, 1968. Florynce Kennedy represented her and asked for a writ of habeas corpus, arguing that Solanas was being held inappropriately at Elmhurst. The judge denied the motion and Solanas returned to Elmhurst. On June 28, Solanas was indicted on charges of attempted murder, assault, and illegal possession of a firearm.[58] She was declared "incompetent" in August and sent to Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.[59] That same month, Olympia Press published the SCUM Manifesto with essays by Girodias and Krassner.[60]

In January 1969, Solanas underwent a psychiatric evaluation and was diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia.[8] In June, she was deemed fit to stand trial. She represented herself without an attorney and pleaded guilty to "reckless assault with intent to harm".[61][62] Solanas was sentenced to three years in prison, with one year of time served.[61][62]

Media response

The shooting of Warhol propelled Solanas into the public spotlight, prompting a flurry of commentary and opinions in the media. Robert Marmorstein, writing in The Village Voice, declared that Solanas "has dedicated the remainder of her life to the avowed purpose of eliminating every single male from the face of the earth".[33] Norman Mailer called her the "Robespierre of feminism".[63] Historian Alice Echols writes that members of New York Radical Women knew "next to nothing" about Solanas until her 1968 shooting of Warhol, but that afterward, Solanas’s case became a cause célèbre among radical feminists, and SCUM Manifesto became "obligatory reading".[64]

Ti-Grace Atkinson, the New York chapter president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), described Solanas as "the first outstanding champion of women's rights"[63] and "a 'heroine' of the feminist movement",[65][66] and "smuggled [her manifesto] ... out of the mental hospital where Solanas was confined".[65][66] According to Betty Friedan, the NOW board rejected Atkinson's statement.[66] Atkinson left NOW and founded another feminist organization.[67] According to Friedan, "the media continued to treat Ti-Grace as a leader of the women's movement, despite its repudiation of her".[68] Kennedy, another NOW member, called Solanas "one of the most important spokeswomen of the feminist movement."[19][69]

English professor Dana Heller argued that Solanas was "very much aware of feminist organizations and activism",[70] but "had no interest in participating in what she often described as 'a civil disobedience luncheon club.'"[70] Heller also stated that Solanas could "reject mainstream liberal feminism for its blind adherence to cultural codes of feminine politeness and decorum which the SCUM Manifesto identifies as the source of women's debased social status".[70]

Imprisonment and psychiatric care

Solanas spent a few weeks at the State Prison for Women at Bedford Hills in May 1970, before being sent back to Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.[71] After escaping from Matteawan in April 1971 and eluding the police for two months, she was apprehended and returned to Matteawan on June 16, 1971.[72] Solanas completed her prison sentence at the end of that month, at which point she was released.[72]

After Solanas was released from Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in June 1971,[73][72] she stalked Warhol and others over the telephone.[62] She harassed publisher Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, demanding $50,000 in payments.[74] In December 1971, Solanas was arrested again for aggravated assault after threatening Barney Rosset, owner of Grove Press and founder of the Evergreen Review, and Fred Jordan, vice president of Grove Press.[75][76]

Solanas was sent to Elmhurst Hospital to undergo psychological examinations.[74] She was declared mentally ill, and the charges against her were dropped.[77] Although they couldn't agree on whether she was dangerous to others, Elmhurst's psychiatrists suggested that she be admitted to a secure state hospital until she recovered.[74] Solanas entered Dunlap-Manhattan Psychiatric Hospital on Wards Island, New York in January 1972.[74] In January 1973, Solanas sent Rosset a letter threatening to kill him: "I'm in the hospital now, but I'll be out soon, + when I get out I'll fix you good. I have a license to kill, you know, + you're one of my candidates. Valerie Solanas."[74]

In February 1973, Solanas escaped from Dunlap-Manhattan Psychiatric Hospital.[78] When Rosset heard this, he hired a private detective from the Pinkertons Detective Agency to find out where she was.[78] The detectives discovered that she had been living at 302 West 22nd Street in Chelsea.[78] They talked to the hotel manager, three people who lived there, and workers at a dry cleaner, but they found no leads. A few weeks later, Solanas called Jordan to rant about the Mob and demanded to be on the cover of the Daily News.[78] She then made an appointment with him to discuss a potential job at Grove Press. Jordan informed the police, and as she went to the Grove Press offices, she was arrested.[79] A court date was set for March 22, 1973. She was sent back to Dunlap and while in custody, her paranoia about the Mob worsened.[78] Rosset and Jordan's lawyers made arrangements with the hospital to keep her there for several more months, allowing her to leave only after she agreed not to harass the two men.[80]

Later career

By 1975, Solanas was eager to write again and reestablish her career.[81] She submitted a poem to Majority Report, a biweekly feminist publication, for a special issue devoted to the work of "authentic street people" who had proposed taking over the paper for an edition titled "The Lesbians Are Coming."[82] Although the paper rarely published poetry, editor Nancy Borman was impressed and printed one of her poems. They also reprinted her 1966 Cavalier article on panhandling—without seeking her permission.[83] When the issue was published, Solanas angrily complained about misspellings, missing copyright, and poor punctuation. After she called the office shouting and "calling herself a punctuation expert," Borman offered her a volunteer editing role, which Solanas accepted.[83][84] Borman recalled that Solanas was "uncannily pleasant," though she was fixated on her past and copyright disputes.[83] Solanas worked diligently and initially didn't disclose that she was the woman who had shot Andy Warhol.[85]

In April 1976, Solanas submitted a letter to the feminist magazine Ms., but it was rejected.[81]

After eighteen months of working at Majority Report, Solanas left the editorial team to focus on writing a new book in 1976.[86] Stepping away meant she could once again publish her writing in the Majority Report, using it to promote SCUM Manifesto and debate other feminists.[86] The publication quickly became her outlet for new ideas and disputes within the women's liberation movement.[86] She outlined the content of her book in the February 19—March 4, 1977 issue:

In my upcoming book I'll explain why I shot Warhol and present an airtight case against various other parasites, many of whom are female ('defenders,' 'interpreters,' etc.), who were sucking my blood about that time. My case will be based partly on a public confession of the money men (not just Maurice Girodias and Warhol) who were involved with me at the time, of all their naughty doings regarding me (paying off to have me declared insane and for massive amounts of bullshit to be written about me, to name just a few things) and the reasons for them. Yes, some of the naughties they must confess to are felonies, but the statute of limitations (7 years) has run out on them. Their public confession is a necessary condition for their getting my next book to publish."[87]

After Olympia Press went bankrupt in 1977 and the rights to SCUM Manifesto reverted to her, she asked Majority Report to typeset a new edition while she kept full editorial control.[88][89] At the editors' urging, she also agreed to three interviews that June—with High Times, The Village Voice, and the New York Daily Planet.[90][91][92] In a second interview with Village Voice, Solanas clarified her book would not be autobiographical outside of a small portion and that it would be about many things, include proof of statements in the manifesto, and would "deal very intensively with the subject of bullshit". In the interview she was also unrepentant about having shot Warhol, saying "I consider it immoral that I missed".[93]

Remove ads

Later life and death

Summarize

Perspective

By the late 1970s, Solanas had largely vanished from public view, with claims that she had become homeless,[94] and her whereabouts became uncertain. In October 1979, her mother filed a missing person report. Solanas—then living in Manhattan's Greenwich Village—was located two weeks later.[95]

Some accounts suggest Solanas had adopted a series of aliases and drifted around the country in the early 1980s while grappling with increasingly severe paranoid schizophrenia.[96]

From 1981 to 1985, Solanas was homeless and living primarily outdoors in Phoenix, Arizona.[97] Former Phoenix police officer and writer Bud Vasconcellos (pen name Bud Maxwell) recalled encountering her beginning in the spring of 1981: "The first time I ran into Valerie Solanas I was working the downtown afternoon beat and we got dispatched the radio code of a 918, saying that there was an insane person, a white female in her mid-forties, standing in the middle of Central and Washington, wearing a nightgown, and crowing like a chicken. She was stopping traffic."[97] For the next three years, Vasconcellos and his partner saw Solanas almost daily. In summer, she wore sneakers to avoid burning her feet; in winter she often went barefoot.[98] She always ran when they approached, and with no grounds to arrest her, they had to let her go, sometimes watching her howl as she wandered off.[98] Eventually, Vasconcellos got close enough to see that her body was covered in scabs. At first, he thought she had a disease, but later realized she carried a kitchen fork and would sit on curbs or park benches, scraping her skin until it bled.[98] Within the Phoenix Police Department, she became known as "Scab Lady."[98] He last saw her in late summer 1984, later noting, "She definitely needed to be in a mental hospital. She was a danger to herself and others."[99]

In 1985, Solanas eventually made her way to San Francisco, a city notorious for its homeless population.[100] She spent her final three years there, first at 149 Ninth Street and later in room 420 of the Bristol Hotel on Mason Street, a single-room-occupancy welfare hotel on the edge of the drug-ridden Tenderloin district.[100] A building superintendent at the hotel had a vague memory of Solanas: "Once, he had to enter her room, and he saw her typing at her desk. There was a pile of typewritten pages beside her. What she was writing and what happened to the manuscript remain a mystery."[13][101]

Throughout her time in San Francisco, Solanas seemed to live on a combination of SSI assistance and income from prostitution.[102] Although she no longer used the name Valerie Solanas, traces of her former identity remained. When a reader wrote to High Times asking if she had died, Solanas herself responded to the magazine, saying she was alive, well, and living in California.[103] Her cousin saw the letter and promptly alerted the family to her whereabouts.[103]

Warhol superstar Ultra Violet tracked Solanas down by pretending to be her sister, and arranged to interview Solanas over the phone in November 1987.[104] According to Ultra Violet, Solanas had changed her name to Onz Loh and stated that the August 1968 version of the Manifesto had many errors, unlike her own printed version of October 1967, and that the book had not sold well.[104] Solanas was unaware of Warhol's death until Ultra Violet informed her.[104] When asked how she felt about it, she said, "I don't feel anything."[104]

On April 25, 1988, at the age of 52, Solanas died of pneumonia at the Bristol Hotel in San Francisco.[105] Her mother burned all her belongings posthumously.[13]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Popular culture

Composer Pauline Oliveros released "To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation" in 1970. In the work, Oliveros seeks to explore how, "Both women seemed to be desperate and caught in the traps of inequality: Monroe needed to be recognized for her talent as an actress. Solanas wished to be supported for her own creative work."[106][107]

Actress Lili Taylor played Solanas in the film I Shot Andy Warhol (1996), which focused on Solanas's assassination attempt on Warhol (played by Jared Harris). Taylor won Special Recognition for Outstanding Performance at the Sundance Film Festival for her role.[108] The film's director, Mary Harron, requested permission to use songs by The Velvet Underground but was denied by Lou Reed, who feared that Solanas would be glorified in the film. Six years before the film's release, Reed and John Cale included a song about Solanas, "I Believe", on their concept album about Warhol, Songs for Drella (1990). In "I Believe", Reed sings, "I believe life's serious enough for retribution ... I believe being sick is no excuse. And I believe I would've pulled the switch on her myself." Reed believed Solanas was to blame for Warhol's death from a gallbladder infection twenty years after she shot him.[109]

Up Your Ass was rediscovered in 1999 and produced in 2000 by George Coates Performance Works in San Francisco. The copy Warhol had lost was found in a trunk of lighting equipment owned by Billy Name. Coates learned about the rediscovered manuscript while at an exhibition at The Andy Warhol Museum marking the 30th anniversary of the shooting. Coates turned the piece into a musical with an all-female cast. Coates consulted with Solanas' sister, Judith, while writing the piece, and sought to create a "very funny satirist" out of Solanas, not just showing her as Warhol's attempted assassin.[13][110]

Solanas' life has inspired three plays. Valerie Shoots Andy (2001), by Carson Kreitzer, starred two actors playing a younger (Heather Grayson) and an older (Lynne McCollough) Solanas.[111] Tragedy in Nine Lives (2003), by Karen Houppert, examined the encounter between Solanas and Warhol as a Greek tragedy and starred Juliana Francis as Solanas.[110] In 2011, Pop!, a musical by Maggie-Kate Coleman and Anna K. Jacobs, focused mainly on Warhol (played by Tom Story). Rachel Zampelli played Solanas and sang "Big Gun", described as the "evening's strongest number" by The Washington Post.[112]

Swedish author Sara Stridsberg wrote a semi-fictional novel about Solanas called Drömfakulteten ('The Dream Faculty'), published in 2006. The book's narrator visits Solanas toward the end of her life at the Bristol Hotel. Stridsberg was awarded the Nordic Council's Literature Prize for the book.[113] The novel was later translated into and published in English under the title Valerie, or, The Faculty of Dreams: A Novel in 2019.[114]

In 2006 Solanas was featured in eleventh episode of the second season Adult Swim show The Venture Bros as part of a group called The Groovy Gang. The group was a parody of the Scooby Gang from Scooby-Doo and was made up of parodies of Solanas (Velma), Ted Bundy (Fred), David Berkowitz (Shaggy), Patty Hearst (Daphne), and Groovy (Scooby). In the episode she is voiced by Joanna Adler. Most of her lines in the episode are quotes from the SCUM Manifesto.

Solanas was featured in a 2017 episode of the FX series American Horror Story: Cult, "Valerie Solanas Died for Your Sins: Scumbag". She was played by Lena Dunham.[115] The episode portrayed Solanas as the instigator of most of the Zodiac Killer murders.

In 2022, Up Your Ass was re-published by writer and editor Leah Whitman-Salkin for MIT's Sternberg Press / Montana. This issue included a contribution by the writer Paul B. Preciado.[116][117]

Influence and analysis

Author James Martin Harding explained that, by declaring herself independent from Warhol, after her arrest she "aligned herself with the historical avant-garde's rejection of the traditional structures of bourgeois theater"[118] and that her anti-patriarchal "militant hostility ... pushed the avant-garde in radically new directions".[119] Harding believed that Solanas' assassination attempt on Warhol was its own theatrical performance.[120] At the shooting, she left on a table at the Factory a paper bag containing a gun, her address book, and a sanitary napkin.[121] Harding stated that leaving behind the sanitary napkin was part of the performance,[122] and called "attention to basic feminine experiences that were publically [sic] taboo and tacitly elided within avant-garde circles".[123]

Feminist philosopher Avital Ronell compared Solanas to an array of people: Lorena Bobbitt, a "girl Nietzsche", Medusa, the Unabomber, and Medea.[124] Ronell believed that Solanas was threatened by the hyper-feminine women of the Factory that Warhol liked and felt lonely because of the rejection she felt due to her own butch androgyny. She believed Solanas was ahead of her time, living in a period before feminist and lesbian activists such as the Guerrilla Girls and the Lesbian Avengers.[63]

Solanas has also been credited with instigating radical feminism.[56] Catherine Lord wrote that "the feminist movement would not have happened without Valerie Solanas".[4] Lord believed that the reissuing of the SCUM Manifesto and the disowning of Solanas by "women's liberation politicos" triggered a wave of radical feminist publications. According to Vivian Gornick, many of the women's liberation activists who initially distanced themselves from Solanas changed their minds a year later, developing the first wave of radical feminism.[4] At the same time, perceptions of Warhol were transformed from largely nonpolitical into political martyrdom because the motive for the shooting was political, according to Harding and Victor Bockris.[125] Solanas' idiosyncratic views on gender are a focus of Andrea Long Chu's 2019 book, Females.[126]

Fahs describes Solanas as a contradiction that "alienates her from the feminist movement", arguing that Solanas never wanted to be "in movement" but nevertheless fractured the feminist movement by provoking NOW members to disagree about her case. Many contradictions are seen in Solanas' lifestyle as a lesbian who sexually serviced men, her claim to be asexual, a rejection of queer culture, and a non-interest in working with others despite a dependency on others.[12] Fahs also brings into question the contradictory stories of Solanas' life. She is described as a victim, a rebel, and a desperate loner, yet her cousin says she worked as a waitress in her late 20s and 30s, not primarily as a prostitute, and friend Geoffrey LaGear said she had a "groovy childhood". Solanas also kept in touch with her father throughout her life, despite claiming that he sexually abused her. Fahs believes that Solanas embraced these contradictions as a key part of her identity.[12]

In 2018, The New York Times started a series of delayed obituaries of significant individuals whose importance the paper's obituary writers had not recognized at the time of their deaths. In June 2020, they started a series of obituaries on LGBTQ individuals, and on June 26, they profiled Solanas.[84]

Remove ads

Works

- Up Your Ass (1965)[d]

- "A Young Girl's Primer on How to Attain the Leisure Class", Cavalier (1966)

- SCUM Manifesto (1967)

Notes

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads