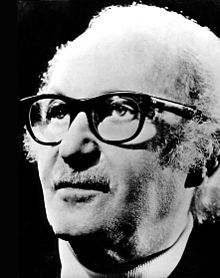

Lee Strasberg

American acting coach and actor (1901–1982) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lee Strasberg (born Israel Strassberg;[1] November 17, 1901 – February 17, 1982) was an American acting coach and actor.[2][3] He co-founded, with theatre directors Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford, the Group Theatre in 1931, which was hailed as "America's first true theatrical collective".[4] In 1951, he became director of the nonprofit Actors Studio in New York City, considered "the nation's most prestigious acting school,"[5] and, in 1966, he was involved in the creation of Actors Studio West in Los Angeles.

Lee Strasberg | |

|---|---|

Strasberg in 1976 | |

| Born | Israel Strassberg November 17, 1901 |

| Died | February 17, 1982 (aged 80) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Westchester Hills Cemetery |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1925–1982 |

| Known for |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 4, including Susan and John |

Although other highly regarded teachers also developed versions of "The Method," Lee Strasberg is considered to be the "father of method acting in America," according to author Mel Gussow. From the 1920s until his death in 1982, "he revolutionized the art of acting by having a profound influence on performance in American theater and film."[1] From his base in New York, Strasberg trained several generations of theatre and film notables, including Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Jane Fonda, Julie Harris, Paul Newman, Ellen Burstyn, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Sally Field, Renee Taylor,[6] Geraldine Page, Eli Wallach, and directors Andreas Voutsinas, Frank Perry, Elia Kazan and Michael Cimino.[1][7]

By 1970, Strasberg had become less involved with the Actors Studio and, with his third wife, Anna Strasberg, opened the Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute with branches in New York City and in Hollywood, to continue teaching the 'system' of Konstantin Stanislavski, which he had interpreted and developed, particularly in light of the ideas of Yevgeny Vakhtangov, for contemporary actors.

As an actor, Strasberg is best known for his portrayal of the primary antagonist, the gangster Hyman Roth, alongside his former student Al Pacino in The Godfather Part II (1974), a role he took at Pacino's suggestion after Kazan turned down the role, and which earned him a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. He also appeared in Going in Style (1979) and ...And Justice for All (1979).[8]

Early years

Summarize

Perspective

Lee Strasberg was born Israel Strassberg in Budzanów in Austrian Poland (part of Austria-Hungary, now in Ukraine), to Jewish parents,[9] Baruch Meyer Strassberg and his wife, Ida (born Chaia), née Diner, and was the youngest of three sons. His father emigrated to New York while his family remained in their home village with an uncle, a rabbinical teacher. His father, who worked as a presser in the garment industry, sent first for his eldest son and his daughter. Finally, enough money was saved to bring over his wife and his two remaining sons. In 1909 the family was reunited on Manhattan's Lower East Side, where they lived until the early 1920s. Young Strasberg took refuge in voracious reading and the companionship of his older brother, Zalmon, whose death in the 1918 influenza pandemic was so traumatic for the young Strasberg that, despite being a straight-A student, he dropped out of high school.[10]

A relative introduced him to the theatre by giving him a small part in a Yiddish-language production being performed by the Progressive Drama Club. He later joined the Chrystie Street Settlement House's drama club. Philip Loeb, casting director of the Theater Guild, sensed that Strasberg could act, although he was not yet thinking of a full-time acting career and was still working as a shipping clerk and bookkeeper for a wig company. When he was 23 years old, he enrolled in the Clare Tree Major School of the Theater. He became a naturalized United States citizen on January 16, 1939, in New York City at the New York Southern District Court.[citation needed]

Encounter with Stanislavski

Summarize

Perspective

Kazan biographer Richard Schickel described Strasberg's first experiences with the art of acting:

He dropped out of high school, worked in a shop that made hairpieces, drifted into the theater via a settlement house company and ... had his life-shaping revelation when Stanislavski brought his Moscow Art Theatre to the United States in 1923. He had seen good acting before, of course, but never an ensemble like this with actors completely surrendering their egos to the work. ... [H]e observed, first of all, that all the actors, whether they were playing leads or small parts, worked with the same commitment and intensity. No actors idled about posing and preening (or thinking about where they might dine after the performance). More important, every actor seemed to project some sort of unspoken, yet palpable, inner life for his or her character. This was acting of a sort that one rarely saw on the American stage ... where there was little stress on the psychology of the characters or their interactions. ... Strasberg was galvanized. He knew that his own future as an actor—he was a slight and unhandsome man—was limited. But he soon perceived that as a theoretician and teacher of this new 'system' it might become a major force in American theater.[11]

Strasberg eventually left the Clare Tree Major School to study with students of Stanislavski — Maria Ouspenskaya and Richard Boleslawski — at the American Laboratory Theatre. In 1925, Strasberg had his first professional appearance in Processional, a play produced by the Theater Guild.[12]

According to Schickel:

What Strasberg ... took away from the Actors Lab was a belief that just as an actor could be prepared physically for his work with dance, movement, and fencing classes, he could be mentally prepared by resort to analogous mental exercises. They worked on relaxation as well as concentration. They worked with nonexistent objects that helped prepare them for the exploration of equally ephemeral emotions. They learned to use "affective memory," as Strasberg called the most controversial aspect of his teaching—summoning emotions from their own lives to illuminate their stage roles. ... Strasberg believed he could codify this system, a necessary precursor to teaching it to anyone who wanted to learn it. ... [H]e became a director more preoccupied with getting his actors to work in the "correct" way than he was in shaping the overall presentation.[11]

Acting director and teacher

Summarize

Perspective

Group Theater

He gained a reputation with the Theater Guild of New York and helped form the Group Theater in New York in 1931.[13] There, he created a technique that became known as "The Method" or "Method Acting". His teaching style owed much to the Russian practitioner, Konstantin Stanislavski, whose book, An Actor Prepares (published in English in 1936), dealt with the psychology of acting. He began by directing, but his time was gradually taken up by the training of actors. Called "America's first true theatrical collective," the Group Theater immediately offered a few tuition-free scholarships for its three-year program to "promising students."[14]

Publishers Weekly wrote, "The Group Theatre ... with its self-defined mission to reconnect theater to the world of ideas and actions, staged plays that confronted social and moral issues ... with members Harold Clurman, Lee Strasberg, Stella, and Luther Adler, Clifford Odets, Elia Kazan, and an ill-assorted band of idealistic actors living hand to mouth are seen welded in a collective of creativity that was also a tangle of jealousies, love affairs, and explosive feuds."[15] Playwright Arthur Miller said, "the Group Theatre was unique and probably will never be repeated. For a while it was literally the voice of Depression America." Co-founder Harold Clurman, in describing what Strasberg brought to the Group Theater, wrote:

Lee Strasberg is one of the few artists among American theater directors. He is the director of introverted feeling, of strong emotion curbed by ascetic control, sentiment of great intensity muted by delicacy, pride, fear, shame. The effect he produces is a classic hush, tense and tragic, a constant conflict so held in check that a kind of beautiful spareness results. The roots are clearly in the intimate experience of a complex psychology, an acute awareness of human contradiction and suffering.[1]

Strasberg, Kazan, Clurman, and others with the Group Theater spent the summer of 1936 at Pine Brook Country Club, located in the countryside of Nichols, Connecticut.[16][17] They spent previous summers at various places in upstate New York and near Danbury, Connecticut.

Amid internecine tensions, Strasberg resigned as director of the Group Theatre in March 1937.[18]

Actors Studio

In 1947, Elia Kazan, Robert Lewis, and Cheryl Crawford, also members of the Group Theatre, started the Actors Studio as a nonprofit workshop for professional and aspiring actors to concentrate on their craft away from the pressures of the commercial theatre.[13] Strasberg assumed leadership of the studio in 1951 as its artistic director. "As a teacher and acting theorist, he revolutionized American actor training and engaged such remarkable performers as Kim Hunter, Marilyn Monroe, Julie Harris, Paul Newman, Geraldine Page, Ellen Burstyn, and Al Pacino." Since its inception, the Studio has been a nonprofit educational corporation chartered by the state of New York, and has been supported entirely by contributions and benefits. "We have here the possibility of creating a kind of theatre that would be a shining medal for our country," Strasberg said in 1959. UCLA acting teacher Robert Hethmon writes, "The Actors Studio is a refuge. Its privacy is guarded ferociously against the casual intruder, the seeker of curiousities, and the exploiter... The Studio helps actors to meet the enemy within... and contributes greatly to Strasberg's utterly pragmatic views on training the actor and solving his problems... [The Studio] is kept deliberately modest in its circumstances, its essence being the private room where Lee Strasberg and some talented actors can work."

Strasberg wrote, "At the studio, we do not sit around and feed each other's egos. People are shocked how severe we are on each other."[1] Admission to the Actors Studio was usually by audition with more than a thousand actors auditioning each year and the directors usually conferring membership on only five or six. "The Studio was, and is sui generis," said Elia Kazan, proudly. Beginning in a small, private way, with a strictly off-limits-to-outsiders policy, the Studio quickly earned a high reputation in theatre circles. "It became the place to be, the forum where all the most promising and unconventional young actors were being cultivated by sharp young directors."[19] Actors who have worked at the studio include Julie Harris, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Geraldine Page, Maureen Stapleton, Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Patricia Neal, Rod Steiger, Mildred Dunnock, Eva Marie Saint, Eli Wallach, Anne Jackson, Ben Gazzara, Sidney Poitier, Karl Malden, Gene Wilder, Shelley Winters, Dennis Hopper, and Sally Field.[5][1]

The Emmy Award-winning author of Inside Inside, James Lipton, writes that the Actors Studio became "one of the most prestigious institutions in the world" as a result of its desire to set a higher "standard" in acting.[5] The founders, including Strasberg, demanded total commitment and extreme talent from aspiring students. Jack Nicholson auditioned five times before he was accepted; Dustin Hoffman, six times; and Harvey Keitel, 11 times. After each rejection, a candidate had to wait as long as a year to try again. Martin Landau and Steve McQueen were the only two students admitted one year, out of 2000 candidates who auditioned.[5]

- Al Pacino: "The Actors Studio meant so much to me in my life. Lee Strasberg hasn't been given the credit he deserves. Brando doesn't give Lee any credit... Next to Charlie Laughton (an acting teacher at HB Studio, and not to be confused with English actor Charles Laughton), it sort of launched me. It really did. That was a remarkable turning point in my life. It was directly responsible for getting me to quit all those jobs and just stay acting."[20]

- Marlon Brando: Movie stars spawned by Strasberg's Actors Studio were of a new type that is often labeled the "rebel hero," wrote Pamela Wojcik. Historian Sam Staggs writes that "Marlon Brando was the hot, sleek engine on the Actors Studio express," and called him "[the] embodiment of method acting,"[21] but Brando was trained primarily by Stella Adler, a former member of the Group Theatre, who had a falling out with Strasberg over his interpretations of Stanislavsky's ideas." He based his acting technique on the method, once stating, "It made me a real actor. The idea is you learn to use everything that happened in your life and you learn to use it in creating the character you're working on. You learn how to dig into your unconscious and make use of every experience you've ever had."[1] In Brando's autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me, the actor claimed he learned nothing from Strasberg: "After I had some success, Lee Strasberg tried to take credit for teaching me how to act. He never taught me anything. He would have claimed credit for the sun and the moon if he believed he could get away with it. He tried to project himself as an acting oracle and guru. Some people worshiped him, and I never knew why. I sometimes went to the Actors Studio on Saturday mornings because Elia Kazan was teaching, and there were usually a lot of good-looking girls there, but Strasberg never taught me acting. Stella did—and later Kazan."[22]

- James Dean: According to James Dean biographer W. Bast, "Proud of this accomplishment, Dean referred to the studio in a 1952 letter, when he was 21 years old, to his family as '... the greatest school of the theater. It houses great people like Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, Arthur Kennedy, Mildred Dunnock. ... Very few get into it. ... It's the best thing that can happen to an actor. I'm one of the youngest to belong.'"[23]

- Marilyn Monroe: Film author Maurice Zolotow wrote: "Between The Seven Year Itch and Some Like It Hot only four years elapsed, but her world had changed. She had become one of the most celebrated personalities in the world. She had divorced Joe DiMaggio. She had married Arthur Miller. She had become a disciple of Lee Strasberg. She was seriously studying acting. She was reading good books."[24]

- Tennessee Williams: Tennessee Williams' plays have been populated by graduates of the studio, where he felt, "studio actors had a more intense and honest style of acting." He wrote, "They act from the inside out. They communicate emotions they really feel. They give you a sense of life."[1] Williams was a co-founder of the group and a key member of its playwright's wing; he later wrote A Streetcar Named Desire, Brando's greatest early role.[25]

- Jane Fonda: Jane Fonda recalled that at the age of 5, her brother, actor Peter Fonda, and she acted out Western stories similar to those her father, Henry Fonda, played in the movies. She attended Vassar College and went to Paris for two years to study art. Upon returning, she met Lee Strasberg and the meeting changed the course of her life, Fonda saying, "I went to the Actors Studio and Lee Strasberg told me I had talent. Real talent. It was the first time that anyone, except my father—who had to say so—told me I was good. At anything. It was a turning point in my life. I went to bed thinking about acting. I woke up thinking about acting. It was like the roof had come off my life!"[26]

Teaching methods and philosophy

Summarize

Perspective

In describing his teaching philosophy, Strasberg wrote, "The two areas of discovery that were of primary importance in my work at the Actors Studio and in my private classes were improvisation and affective memory. It is finally by using these techniques that the actor can express the appropriate emotions demanded of the character."[27] Strasberg demanded great discipline of his actors, as well as great depths of psychological truthfulness. He once explained his approach in this way:

The human being who acts is the human being who lives. That is a terrifying circumstance. Essentially, the actor acts a fiction, a dream; in life, the stimuli to which we respond are always real. The actor must constantly respond to stimuli that are imaginary. And yet this must happen not only just as it happens in life, but [also] actually more fully and more expressively. Although the actor can do things in life quite easily, when he has to do the same thing on the stage under fictitious conditions, he has difficulty because he is not equipped as a human being merely to playact at imitating life. He must somehow believe. He must somehow be able to convince himself of the rightness of what he is doing in order to do things fully on the stage.

According to film critic and author Mel Gussow, Strasberg required that an actor, when preparing for a role, delve not only into the character's life in the play but also, "Far more importantly, into the character's life before the curtain rises. In rehearsal, the character's prehistory, perhaps going back to childhood, is discussed and even acted out. The play became the climax of the character's existence."[1]

Elia Kazan as student

In Elia Kazan's autobiography, the Academy Award–winning director wrote about his earliest memories of Strasberg as teacher:

He carried with him the aura of a prophet, a magician, a witch doctor, a psychoanalyst, and a feared father of a Jewish home. He was the center of the camp's activities that summer, the core of the vortex. Everything in camp revolved around him. Preparing to direct the play that was to open the coming season, as he had the three plays of the season before, he would also give the basic instruction in acting, laying down the principles of the art by which the Group worked, the guides to their artistic training. He was the force that held the thirty-odd members of the theatre together, made them 'permanent.' He did this not only by his superior knowledge but by the threat of his anger. ... He enjoyed his eminence just as the admiral would. Actors are as self-favoring as the rest of humanity, and perhaps the only way they could be held together to do their work properly was by the threat of an authority they respected. And feared. No one questioned his dominance—he spoke holy writ—his leading role in that summer's activities, and his right to all power. To win his favor became everyone's goal. His explosions of temper maintained the discipline of this camp of high-strung people. I came to believe that without their fear of this man, the Group would fly apart, everyone going in different directions instead of to where he was pointing. ... I was afraid of him too. Even as I admired him. Lee was making an artistic revolution and knew it. An organization such as the Group – then in its second year, which is to say still beginning, still being shaped—lives only by the will of a fanatic and the drive with which he propels his vision. He has to be unswerving, uncompromising, and unadjustable. Lee knew this. He'd studied other revolutions, political and artistic. He knew what was needed, and he was fired up by his mission and its importance.[28]: 59

Classroom settings

Kazan described the classes taught by Strasberg:

At his classes in the technique of acting, Lee laid down the rules, supervised the first exercises. These were largely concerned with the actor's arousing his inner temperament. The essential and rather simple technique, which has since then been complicated by teachers of acting who seek to make the Method more recondite for their commercial advantage, consists of recalling the circumstances, physical and personal, surrounding an intensely emotional experience in the actor's past. It is the same as when we accidentally hear a tune we may have heard at a stormy or an ecstatic moment in our lives, and find, to our surprise, that we are reexperiencing the emotion we felt then, feeling ecstasy again or rage and the impulse to kill. The actor becomes aware that he has emotional resources; that he can awaken, by this self-stimulation, a great number of very intense feelings; and that these emotions are the materials of his art. ... Lee taught his actors to launch their work on every scene by taking a minute to remember the details surrounding the emotional experience in their lives that would correspond to the emotion of the scene they were about to play. 'Take a minute!' became the watchword of that summer, the phrase heard most often, just as this particular kind of inner concentration became the trademark of Lee's own work when he directed a production. His actors often appeared to be in a state of self-hypnosis.[28]: 61

James Dean

In 1955 Strasberg student James Dean died in a car accident, at age 24. Strasberg, during a regular lecture shortly after this accident, discussed Dean. The following are excerpts from a transcription of his recorded lecture:

(In the middle of his lecture on another topic) To hell with it! I hadn't planned to say this, because I don't know how I'll behave when I say it; I don't think it will bother me. But I saw Jimmy Dean in Giant the other night, and I must say that— (he weeps) You see, that's what I was afraid of. [A long pause] When I got in the cab, I cried. ... What I cried at was the waste, the waste. ... If there is anything in the theatre to which I respond more than anything else—maybe I'm getting old, or maybe I'm getting sentimental—it is the waste in the theatre, the talent that gets up and the work that goes into getting it up and getting it where it should be. And then when it gets there, what the hell happens with it? The senseless destruction, the senseless waste, the hopping about from one thing to the next, the waste of the talent, the waste of your lives, the strange kind of behavior that not just Jimmy had, you see, but that a lot of you here have and a lot of other actors have that are going through exactly the same thing. ... As soon as you grow up as actors, as soon as you reach a certain place, there it goes, the drunkenness and the rest of it, as if, now that you've really made it, the incentive goes, and something happens which to me is just terrifying. I don't know what to do. ... The only answer possibly is that we somehow here find a way, a means, an organization, a plan [that] should really contribute to the theatre, so that there should not only be the constant stimulus to your individual development, which I think we have provided, but also that once your individual development is established, it should then actually contribute to the theatre, rather than to an accidental succession of good, bad, or indifferent things. But I am very, very scared that despite how strongly I feel, or despite how stimulated you become, nothing will be done. ... [A]nd we will just continue to get so caught up that in a strange way we do not really live our lives. ... To me that is the future of the Studio, that a unified body of people should somehow be connected with a tangible, consistent, and continuous effort. That is the dream I have always had. That is what got me into theatre in the first place. That was the thing that got me involved in The Actors Studio ... and now it becomes time to think a little bit more about our responsibility for that individual talent. ... I'm stuck. I don't know. And this is really the problem of the Studio.

On Marilyn Monroe

In 1962, Marilyn Monroe died at age 36. At the time of her death, she was at the height of her career. In 1999, she was ranked the sixth-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema by the American Film Institute. Lee Strasberg gave the eulogy at her funeral.[29][30]

For us, Marilyn was a devoted and loyal friend—a colleague constantly reaching for perfection. We shared her pain and difficulties, and some of her joys. She was a member of our family. ... It is difficult to accept the fact that her zest for life has been ended by this dreadful accident. Despite the heights and brilliance she had attained on the screen, she was planning for the future. She was looking forward to participating in the many exciting things. In her eyes, and in mine, her career was just beginning. ... She had a luminous quality. A combination of wistfulness, radiance, and yearning that set her apart and made everyone wish to be part of it—to share in the childish naiveté which was at once so shy and yet so vibrant.

Personal life

Lee Strasberg's first marriage was to Nora Krecaum from October 29, 1926, until her death three years later in 1929. In 1934, he married actress and drama coach Paula Miller (1909–1966) until her death from cancer in 1966. Lee and Paula were the parents of actress Susan Strasberg (1938–1999) and acting teacher John Strasberg (born 1941). His third wife was the former Anna Mizrahi (born April 16, 1939) and the mother of his two youngest children, Adam Lee Strasberg (born July 29, 1969) and David Lee Israel Strasberg (born January 30, 1971).

Death and commemoration

Summarize

Perspective

Lee Strasberg suffered a fatal heart attack on February 17, 1982, in New York City, aged 80.[1][31] With him at the time of his death at the hospital were his third wife, Anna, and their two sons. He was interred at Westchester Hills Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. A day before his unexpected death, he was officially notified that he had been elected to the American Theater Hall of Fame. His last public appearance was on February 14, 1982, at Night of 100 Stars in the Radio City Music Hall, a benefit for the Actors Fund of America. Along with Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, he danced in the chorus line with The Rockettes.[1]

Actress Ellen Burstyn recalled that evening:

Late in the evening, I wandered into the greenroom and saw Lee sitting next to Anna, watching the taping on the monitor. I sat next to him and we chatted a little. Lee wasn't one for small talk, so I didn't stay long. But before I got up, I said, 'Lee, I've been asked to run for president of Actors Equity.' He reached over and patted me on the back, 'That's wonderful, dahling. Congratulations.' Those were the last words he ever said to me. ... Two days later, early in the morning, I was still asleep when the door to my bedroom opened. I woke up and saw my friend and assistant, Katherine Cortez, enter the room and walk toward me. ... 'We just got a call. Lee Strasberg died.' No, no, no, I wailed, over and over. 'I'm not ready,' and pulled the covers over my head. I had told myself that I must be prepared for this, but I was not prepared. What was I to do now? Who would I work for when I was preparing for a role? Who would I go to when I was in trouble?. ... His memorial service was held at the Shubert Theater where A Chorus Line was playing. Lee's coffin was brought down the aisle and placed center stage. Everybody in the theater world came—actors, writers, directors, producers, and most, if not all of, his students. He was a giant of the theater and was deeply mourned. Those of us who had the great good fortune to be fertilized and quickened by his genius would feel the loss of him for the rest of our lives.[32]

In an 80th birthday interview, he said that he was looking forward to his next 20 years in the theater. According to friends, he was healthy until the day he died. "It was so unexpected," Al Pacino said. "What stood out was how youthful he was. He never seemed as old as his years. He was an inspiration." Actress Jane Fonda said after hearing of his death, "I'm not sure I even would have become an actress were it not for him. He will be missed, but he leaves behind a great legacy."

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

"Whether directly influenced by Strasberg or not," wrote acting author Pamela Wojcik, "the new male stars all to some degree or other adapted method techniques to support their identification as rebels.... He recreates romance as a drama of male neuroticism and also invests his characterization 'with an unprecedented aura of verisimilitude.'"[33] Acting teacher and author Alison Hodge explains, "Seemingly spontaneous, intuitive, brooding, 'private,' lit with potent vibrations from an inner life of conflict and contradiction, their work exemplified the style of heightened naturalism which (whether Brando agrees or not) Lee Strasberg devoted his life to exploring and promoting."[34] Pamela Wojcik adds:

Because of their tendency to substitute their personal feelings for those of the characters they were playing, Actors Studio performers were well suited to become Hollywood stars. ... In short, Lee Strasberg transformed a socialistic, egalitarian theory of acting into a celebrity-making machine. ... It does not matter who 'invented' Marlon Brando or how regularly or faithfully he, Dean, or Clift attended the Studio or studied the method at the feet of Lee Strasberg. In their signature roles—the most influential performances in the history of American films—these three performers revealed new kinds of body language and new ways of delivering dialogue. In the pauses between words, in the language 'spoken' by their eyes and faces, they gave psychological realism an unprecedented charge. Verbally inarticulate, they were eloquent 'speakers' of emotion. Far less protective of their masculinity than earlier film actors, they enacted emotionally wounded and vulnerable outsiders struggling for self-understanding, and their work shimmered with a mercurial neuroticism ... [T]he method-trained performers in films of the '50s added an enhanced verbal and gesture naturalism and a more vivid inner life.[34]

In 2012, Strasberg's family donated his library of personal papers to the Library of Congress. The papers include 240 boxes containing correspondence, rehearsal notes, photographs, theatrical drawings and posters, sketches of stage designs, and more.[35]

Lee Strasberg, his wife Paula, his daughter Susan, and his son John, all appear as characters in Robert Brustein's 1998 play Nobody Dies on Friday, which one critic called a "scathing portrait of Strasberg," but one that "can by no means be dismissed as a simple act of character assassination." Brustein, a critic, director, and producer, had previously made public his dislike of the method as a philosophy of acting. The play was produced by Brustein's American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was later presented in Singapore.[36]

Strasberg is a character in Names, Mark Kemble's play about former Group Theatre members' struggles during the blacklist era.[37]

In 2020, Google Arts & Culture, together with Giovanni Morassutti, an Italian actor who has deepened the study of The Method and long-time collaborator of John Strasberg, have created an online exhibition named Strasberg Legacy tracing the history of the realistic school of acting.[38]

Broadway credits

Summarize

Perspective

Note: All works are plays and the original productions, unless otherwise noted.

- Four Walls (1927) – actor

- The Vegetable (1929) – director

- Red Rust (1929) – actor

- Green Grow the Lilacs (1931) – actor

- The House of Connelly (1931) – codirector

- 1931 (1931) – director

- Success Story (1932) – director

- Men in White (1933) – director

- Gentlewoman (1934) – director

- Gold Eagle Guy (1934) – director

- Paradise Lost (1935) – produced by Group Theatre

- Case of Clyde Griffiths (1936) – director, produced by Group Theatre

- Johnny Johnson (1936) – director, produced by Group Theatre

- Many Mansions (1937) – director

- Golden Boy (1937) – produced by Group Theatre

- Roosty (1938) – director

- Casey Jones (1938), produced by Group Theatre

- All the Living (1938) – director

- Dance Night (1938) – director

- Rocket to the Moon (1938) – produced by Group Theatre

- The Gentle People (1939) – produced by Group Theatre

- Awake and Sing! (1939), revival – produced by Group Theatre

- Summer Night (1939) – director

- Night Music (1940) – produced by Group Theatre

- The Fifth Column (1940) – director

- Clash by Night (1941) – director

- A Kiss for Cinderella (1942), revival – director

- R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) (1942), revival – director

- Apology (1943) – producer and director

- South Pacific (1943, apparently no relation to the Broadway musical South Pacific) – director

- Skipper Next to God (1948) – director

- The Big Knife (1949) – director

- The Closing Door (1949) – director

- The Country Girl (1950) – co-producer

- Peer Gynt (1951), revival – director

- Strange Interlude (1963), revival – produced by The Actors Studio – Tony Award co-nomination for Best Producer of a Play

- Marathon '33 (1963) – production supervisor

- Three Sisters (1964), revival – director, produced by the Actors Studio

Film credits

- Parnell (1937) as Pat (uncredited)[39]

- China Venture (1953) as Patterson[40]

- The Godfather Part II (1974; nominated, Academy Award Best Actor in a Supporting Role) as Hyman Roth[41]

- The Cassandra Crossing (1977) as Herman Kaplan[41]

- The Last Tenant (1978, TV movie).[41][42]

- ...And Justice for All (1979) as Sam Kirkland[41]

- Boardwalk (1979) as David Rosen[41]

- Going in Style (1979) as Willie[42]

- Skokie (1981, TV movie) as Morton Weisman[42]

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.