Song Cycle (album)

1967 album by Van Dyke Parks From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Song Cycle is the debut album by the American recording artist Van Dyke Parks, released in November 1967 by Warner Bros. Records. Named after the 19th-century classical format, it is an autobiographical concept album centered on Hollywood and southern California, blending orchestral pop with elements of Tin Pan Alley songwriting, bluegrass, ragtime, and musique concrète.[1] Its lyrics follow his usual style of free-associative wordplay while traversing subjects ranging from war and artistic struggle to societal disparity. Provisionally titled Looney Tunes, he characterized his approach as embodying a "cartoon consciousness".

| Song Cycle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | November 1967 | |||

| Recorded | Early to mid–1967 | |||

| Studio | Various, including Sound Recorders and Sunset Sound (Hollywood) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 32:39 | |||

| Label | Warner Bros. | |||

| Producer | Lenny Waronker | |||

| Van Dyke Parks chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Song Cycle | ||||

| ||||

Granted unprecedented creative control and funding for an unproven artist, Parks wrote Song Cycle during a label-sponsored retreat to Palm Desert, California following collaborations with Brian Wilson (Smile), Harpers Bizarre, and the Mojo Men. Recorded over seven months at Hollywood studios such as Sunset Sound Recorders, the sessions were produced by Lenny Waronker, engineered by Lee Herschberg and Doug Botnick, and mixed by Bruce Botnick. Over 50 session musicians contributed, including members of the Wrecking Crew. The production emphasized spatial experimentation inspired by Juan García Esquivel's stereo panning techniques, as well as Leslie-processed vocals, studio manipulation, sampling, unconventional instruments, and layered textures.

Song Cycle was one of the most expensive albums ever produced, costing approximately $80,000 (equivalent to $750,000 in 2024). Upon release, it elicited positive reviews from critics associated with the New Journalism movement, but yielded confusion from retailers, radio programmers, and the label's marketing staff. To address poor sales, the company, without consulting Parks, launched an unconventional ad campaign declaring the album a commercial flop. Parks and Waronker subsequently produced Randy Newman's 1968 self-titled debut. After recouping from the production costs of Song Cycle, Warner issued Parks' follow-up Discover America (1972).

Though its legacy has often been overshadowed by Parks' connection to Smile, Song Cycle influenced the 1970s singer-songwriter movement and inspired many other recording artists to experiment with studio artifice. The Newman-composed opening track "Vine Street", written for and about Parks, later received covers by Harry Nilsson and Lulu. Other artists influenced by the album have included Joanna Newsom, Jim O'Rourke, Keiichi Suzuki, and the High Llamas.

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Van Dyke Parks' first visit to Hollywood involved a minor acting role in the 1956 film The Swan, starring Grace Kelly.[2][nb 1] In 1960, he enrolled at the Carnegie Institute as a music major, focusing on composition and performance until 1963, when he switched to the requinto guitar. He then joined his brother Carson in the folk duo the Steeltown Two, performing along California's coast for minimal pay; their earnings later rose to $750 weekly at West Hollywood's Troubadour (equivalent to $7,700 in 2024).[5] In 1963, Parks' brother Benjamin, a French horn player and State Department employee, died in a car accident in Frankfurt under circumstances suggesting Cold War ties. To relieve the Parks family of funeral expenses, songwriter Terry Gilkyson commissioned Parks to arrange "The Bare Necessities" for Disney's The Jungle Book (1967), providing Parks his first major gig in the Hollywood music industry.[6] In the mid-1960s, Parks established himself as a versatile session keyboardist, working with artists ranging from folk singer Tim Buckley to rock groups the Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders.[7]

In 1966, Parks met Beach Boys producer Brian Wilson at Terry Melcher's home, leading to their collaboration on the band's unfinished album Smile.[8][nb 2] That year, Parks briefly signed with MGM Records under A&R executive Tom Wilson.[10] Two singles emerged: "Come to the Sunshine", referencing his father's dance band, and "Number Nine", a folk-rock adaptation of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy".[11] The singles received little attention, though music historian Richard Henderson writes that their "lyric sleight-of-hand, vivacious melodies, and pell-mell arrangements" cemented the template for Song Cycle.[11] By then, Parks and his brother resided in sparse Hollywood apartments above a hardware store owned by the parents of music producers and engineers Bruce and Doug Botnick.[12] Immersed in Southern California's folk scene during these years, he briefly formed a guitar trio with musician Stephen Stills and singer-songwriter Steve Young.[13]

Coinciding with a transformative period for the label, Parks joined Warner Bros. Records through producer Lenny Waronker, a young A&R executive mentored by Reprise Records president Mo Ostin.[14] Waronker was tasked with overseeing artists acquired during Warner Bros.' 1966 purchase of Autumn Records, including the Mojo Men, the Beau Brummels, and the Tikis—later renamed Harpers Bizarre by Parks.[15] He assembled a team featuring Parks, songwriter Randy Newman, and keyboardist Leon Russell.[16][15] The success of subsequent singles by Harpers Bizarre and the Mojo Men convinced the label of the group's ability.[15]

After Seven Arts Productions had acquired Warner Bros. in 1966, the record division rebranded as Warner Bros.-Seven Arts under president Joe Smith, who prioritized broadening the label's artistic scope, later recalling, "Los Angeles was a small community ... Van Dyke already had a solid reputation."[17] Parks' intellect and autonomy impressed Smith, who granted him unusual creative control.[18] He signed a multi-album contract with Warner Bros. on January 5, 1967.[19] The agreement included a substantial recording budget, full creative control, no set deadlines,[20] and a clause guaranteeing union-scale payment for sessions produced by Waronker[18]—an extraordinary allowance for an artist like Parks, comparable to the largesses afforded to the Beatles.[21] His availability to Wilson subsequently reduced,[22] and by April, he had withdrawn from the Smile project to focus on Song Cycle.[23]

Concept

Summarize

Perspective

Parks composed much of Song Cycle during a retreat to Palm Desert, California, funded by the label.[24][nb 3] Intended as a concept album about Hollywood and southern California,[2] he later described the work as embodying a "cartoon consciousness", initially titling it Looney Tunes in homage to Warner Bros.' animated shorts.[25][nb 4] The lyrics follow Parks' usual style of free-associative wordplay,[24] influenced by James Joyce.[2] He reflected,

I wanted to capture the sense of California as a Garden of Eden and land of opportunity. It was a very big deal to me: What was this place? What has it become? What will it become? And what does it mean to be here? ... [I wanted Song Cycle to be] relevant to its time and part of the free press of its time, as a watchword to the errant youth that was showing up here in droves.[2]

Song Cycle emerged during the period when the term "concept album" first appeared in the music press.[27] While Frank Sinatra had pioneered thematic album sequencing in the 1950s, Parks' work diverged from contemporary rock trends that often dismissed pre-rock traditions. Instead, Song Cycle drew inspiration from 19th-century song cycles by composers such as Beethoven and Schubert, integrating historical musical forms with the psychedelic era's sensibilities.[28]

Unlike the seamless, cross-faded tracks of contemporaneous concept albums, Song Cycle featured self-contained songs with defined beginnings and endings, functioning as interconnected components of a cohesive whole.[29] Its structure reflected a deliberate continuity, with key modulations referencing Tin Pan Alley conventions, recurring melodic motifs, and deliberate harmonic relationships between codas and subsequent introductions.[30]

Production

Summarize

Perspective

Recording spanned seven months, with tracking supervised by engineer Lee Herschberg and mixing handled by Bruce Botnick at Sunset Sound.[31] Doug Botnick assisted during tracking sessions.[32] The project used scattered studio time across Hollywood, with Waronker and Parks transporting multitrack tapes between facilities. Waronker prioritized access to recording equipment over specific studio acoustics, later recalling, "We weren't crazed over a particular studio's sounds ... just looking for tape recorders."[33][nb 5] Estimates of the total production cost range from $75,000 to $85,000.[34]

Sessions began at Sound Recorders with "Donovan's Colours", released as a single under the pseudonym "George Washington Brown" due to Parks’ reluctance to risk his family's reputation.[33][nb 6] After journalist Richard Goldstein praised "Donovan's Colours" in the Village Voice, Warner Bros. approved the album but required Parks to use his real name.[36] According to Parks, most of the album was recorded before the Beatles' May 1967 release Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band "reared it ugly head".[37] Technical processes mirrored Sgt. Pepper, with tracks recorded on four-track machines, bounced to another four-track, then transferred to eight-track for mixing.[38] Parks and Waronker entered sessions each day without a predetermined plan, aiming to translate Parks' sonic ideas into recordings using any available or improvised methods. The recording process varied widely: some sessions involved large ensembles following fully notated scores, while others featured individual musicians brought in sequentially as Parks arranged parts in real time. At times, only Parks, Waronker, and engineer Herschberg were present, working on keyboard tracks or experimenting with ways to manipulate the existing recordings.[34]

Despite stereo's limited commercial focus at the time—mono mixes remained dominant—the album's mixing approach emphasized spatial experimentation.[39] Parks incorporated techniques inspired by Mexican composer Juan García Esquivel, a pioneer of 1950s space age pop whose innovations—including dynamic stereo panning, tape-speed manipulation for pitch alteration, and eclectic instrumentation such as ondiolines and harpsichords—directly informed Song Cycle.[40][nb 7] Waronker later remarked, "I used to speed up everything. I was taking so much speed back then it just sounded better that way."[42] Parks also adopted Brian Wilson's method of combining instrumental tone colors to create novel textures.[43] Minor differences are present between the stereo and mono mixes of Song Cycle; for example, the mono version of "Donovan's Colours" includes Parks briefly singing the lyric "Blue is the color of the sky".[44]

I had no expectations as to how I'd duplicate [the tracks in a live setting] or make a living, and so I didn't.

—Van Dyke Parks[45]

Song Cycle has been variously categorized as an avant-pop,[46] orchestral pop,[47] Americana,[48] art pop,[49] pop,[50][51] and art rock album.[52] Bruce Botnick described it as an inadvertent "psychedelic masterpiece".[53] Diverging from London's focus on tape manipulation, Los Angeles' late-1960s psychedelic music had centered on studio experimentation and historical instruments such as harpsichord and string ensembles.[54] Immersed in this studio milieu, Parks repurposed technical tools like varispeed controls and regenerated echo effects—typically used for audio correction—to craft experimental textures.[55] According to Henderson, each song was "set in its own virtual landscape", crafted through precise echo, reverberation, and ambient elements like weather, insects, and human activity.[30] Herschberg oversaw initial recordings that applied reverb and echo during tracking rather than mixing, a standard method at the time.[56][nb 8] Bruce employed Sunset Sound's Studio One echo chamber and integrated sound effects from Elektra Records' library, such as train noises on "The All Golden" and nautical sounds like ship horns and waves elsewhere.[58][nb 9] Parks' vocals were processed through a Leslie speaker on almost every track; he later stated that Waronker had encouraged the effect despite anticipating criticism: "We had no fear of artifice. It was the right thing to do."[59][nb 10]

Botnick devised the "Farkle", an improvised tape manipulation technique that involved attaching folded masking or splicing tape to the capstan of a tape machine, creating protruding "fins" that caused irregular movement in the tape transport.[61] The resulting intermittent contact between the tape and record head generated fluctuating echo effects akin to high-tension wires or scrambled radio signals.[62] Botnick employed the Farkle extensively during mixing, becoming a recurring sonic motif throughout Song Cycle.[63] Its name's origin remains unclear; Botnick described its creation as spontaneous problem-solving: "a function of creativity at the moment when you need to do something".[64][nb 11]

Tracks

Summarize

Perspective

Side one

"Vine Street" was composed by Randy Newman at Parks' commission. Newman originally structured the opening segment based around an eighth-note figure with the lyrics "Anita / Ah need yuh", remarking, "It was equally bad as the one he put on the front [of the album]."[66] Instead, the Song Cycle rendition begins with the traditional ballad "Black Jack Davy", performed by Steve Young.[60] Parks explained this decision was motivated by a desire to promote Young: "I wanted to sequence [Song Cycle] with a hierarchy of things that were important to me at the time. ... The fact that he was the only man I had ever met who had to pick cotton and did so, that mattered to me, as well as to the piece."[67] To match the reminiscing musician character portrayed in "Vine Street", Young's recording was deliberately degraded to simulate older recording technology.[60]

Parks' vocal appears with string accompaniment after the tape excerpt—acknowledged in the lyrics—has faded, with a reference to himself on "third guitar", which he later explained was deliberate on Newman's part: "he knew I was the third guitar [in the band with Stephen Stills and Steve Young]."[67] A string arrangement mimicking a Doppler effect precedes the song's title, which Parks included as an homage to the train sounds heard at the end of the Beach Boys' "Caroline, No" from Pet Sounds (1966).[68] He credits the seamless transition into "Palm Desert"—achieved with a dissonant sustained chord—to Newman's input.[24]

"Palm Desert" is a tribute to the Coachella Valley city where Parks wrote the album and includes a lyric quotation of Buddy Holly's 1957 song "Not Fade Away", rhyming the title with "I wish I could stay". Parks described the song as an "antidote" to personal hardship, drawing from memories of financial struggle and his admiration for Australian composer Percy Grainger's folk-inspired chamber works. The melody of the lyric "I came west unto Hollywood" was inspired by a Jell-O commercial jingle; he later characterized this reference as an attempt at pop art.[69] The melodic figure recurs with a lyric that can be interpreted ambiguously as either "dreams are still born in Hollywood" or "stillborn".[42] Accompanied by a trio of French horns, cello, and a harmonica layered atop saxophones, Red Rhodes played a steel guitar that bridges transitions between verses and choruses through fluid pitch-bending.[70][nb 12] Botnick's spatial orchestration of the track panned instruments to opposite stereo channels, leaving the center space for a wooden ratchet that shifts across the soundstage, among other percussive elements, while Parks' multi-part vocals—separated in the mix with distinct delay times—were given split-channel placement.[39]

"Widow's Walk" was composed by Parks to console his aunt following her husband's death from cancer.[39] The track features sparse instrumentation, including a harp accentuating the downbeat, a bass marimba played by Parks, mandolin with a three-against-two polyrhythm, and an accordion alternating between shuffle and straight eighth-note rhythms.[72] Recording sessions involved incremental layering of parts at Sound Recorders. Parks’ voice was pitched up through tape manipulation.[73] Botnick and Parks employed rhythmic tape echo timed to subdivide beats, generating compound rhythms, a novel technique for the era.[74][nb 13]

"Laurel Canyon Blvd" addresses the bohemian subculture surrounding the Los Angeles neighborhood of the same name.[75][nb 14] The track incorporates a balalaika quintet led by Russian émigré violinist Misha Goodatieff. Parks recruited Goodatieff and his cousins, including a bass balalaika player: "they needed the employment and I was there to help."[76]

"The All Golden" is an homage to Steve Young that references his struggles with poverty, including a lyrical nod to his "small apartment atop an Oriental food store", underscored by a pentatonic scale pun.[77] Parks intentionally retained a mid-song collapse of the brass section, performed by Vince DeRosa and others.[78] The track incorporates a brief viola solo by 20th Century Fox studio musician Virginia Majewski and a horn solo by DeRosa, alongside train-like saxophone motifs and a chromatic harmonica evoking a "southern zephyr", according to Parks.[79] He drew thematic inspiration from Will Carleton's Farm Ballads, a 19th-century poetry collection he discovered among his mother's belongings, to critique the transition from agrarian to industrial society.[80] The track opens with a subaquatic atmosphere, created by applying the Farkle effect to harpist Gayle Levant's arpeggios.[61] The outro reprises these harp motifs alongside train sounds symbolizing American expansionism, concluding with a voice asking, "Ja get it? Alright."[79]

"Van Dyke Parks" is an audio collage simulating maritime disaster sounds, including flares, explosions, and a steamship whistle resembling a dying animal. James Hendricks, a former member of the Mugwumps, sings "Nearer My God to Thee", a hymn associated with the Titanic sinking. A chorus abruptly restates the hymn in a different key, a compositional technique Parks described as representing the disconnect between survivors and a sinking ship.[81] He linked this Titanic imagery to 1960s America, addressing the Vietnam War, racial tensions, and political conflicts.[82] Parks characterized the album's first half as reflecting necessary "political consciousness" amid contemporary turmoil, ending with fading flare sounds and a ship horn: "I thought that would be a fun way to [end] the first half of the album. ... I don't think too many people lasted into the second act."[83]

Side two

"Public Domain" blends folk-inspired rhythms and dramatic string arrangements, framed by Parks as both autobiographical and a critique of industrial elitism. It opens with a harp motif influenced by the diatonic Veracruz harp tradition from Mexico, which Parks encountered during travels with his brother.[83] Overdubbed harp layers created a rolling rhythm akin to bluegrass, while Parks' lyrics employed intricate alliteration.[59]

Parks recorded his interpretation of Donovan's "Colours" as a response to Bob Dylan's disparaging treatment of the Scottish musician in the 1967 documentary Don't Look Back, intending the cover as a gesture of support. The basic track was created through layering acoustic, electric, and tack pianos.[44] It opens with a mechanical rhythm generated by a coin-operated music machine owned by Lenny Marvin, an associate of avant-garde composer Harry Partch. Parks captured the device's sounds using a Nagra reel-to-reel recorder, later transferring the recording to four-track tape to serve as its rhythmic foundation. It reflected Parks’ admiration for electro-mechanical soundscapes, influenced by Emory Cook's 1953 EP Barrellhouse Organ. The production included marimba parts recorded at half speed and pitch-shifted during playback.[84] It abruptly transitions to a faster tempo driven by clarinet, with clashing organ and tack piano textures, joked by Parks as "Vincent Price coming out of the wine cellar".[85] A calypso rhythm known as "Whip de lion", taught to Parks by steelpan musician Andrew de la Bastide, underscores sections of the track. The arrangement concludes with reversed tape effects simulating the coin's return to its user.[45]

"The Attic" drew from Parks' childhood memories of exploring his father's World War II trunk in an attic, which contained wartime letters addressed to his mother; his father had served as a psychiatric officer during the Allied advance in Europe and was present at the liberation of Dachau.[86][nb 15] The track employed eight cellos performing alternating on-beat and off-beat patterns across the stereo field, accompanied by a snare drum accentuating the lyrical themes of discovery and reflection. Henderson felt the track represented the album's closest resemblance to "a production from the golden age of radio, a feeling underscored by Gayle Levant's sweeping harp glissandi; one half expects to hear a commercial for Ovaltine following its conclusion."[45] Botnick integrated effects from Sunset Sound's library—including creaking trunk hinges, insect drones, and birdsong—to match the lyrical imagery.[86]

The second "Laurel Canyon Blvd" reprises his earlier homage to Los Angeles' bohemian enclave, structured in two movements. The second movement includes vocals processed through a Farkle; a string band arrangement underscores Parks' lyrical depiction of commuters intersecting with fringe figures in the Canyon. Goodatieff contributed violin to the track.[86]

"By the People" is the album's most overtly political composition, addressing Cold War tensions through Andrews Sisters-inspired vocal harmonies, extended pauses bridged by decaying tape echoes, and a spatially dislocated violin solo. Lyrically, it draws parallels between the American South and czarist Russia. The track opens with a tremulous violin arpeggio by Goodatieff, intended to evoke Cold War-era anxiety.[87] Parks incorporated balalaikas, embracing the Brazilian concept of desafinado—imperfect tuning that yields expressive texture—through their doubled strings.[88][nb 16] Parks cited influences ranging from White Russian émigrés in the U.S. to the pervasive intrigue of the post-Cuban Missile Crisis era, alongside personal reflections on his brother Ben's mysterious death.[90] The song employed wordplay: "I thought about Caucasus and Georgia, and those became a springboard for puns, more lyrics born of a free relationship in meaning."[91]

"Pot Pourri", likely the final track produced, contrasts the rest of the album with minimalistic production, recorded in a single take on two tracks of an eight-track tape.[91] Its subdued vocals and sparse instrumentation reflect Parks' intention to simulate a distant observer's perspective.[92] The lyrics, influenced by Lawrence Ferlinghetti's poetry, center on a Japanese gardener tending a wisteria vine outside Parks' home, juxtaposed with allusions to the attack on Pearl Harbor.[93] Parks later described himself as a "war baby" shaped by the historical event, using the song to reconcile admiration for Nisei cultural contributions—particularly in landscaping—with Japan's wartime conduct. Doug Botnick likened the track's quiet conclusion to classical song cycles that favor understatement over grandeur, calling it a “simple ending to a complicated, more sophisticated piece."[92]

Packaging and sleeve design

Summarize

Perspective

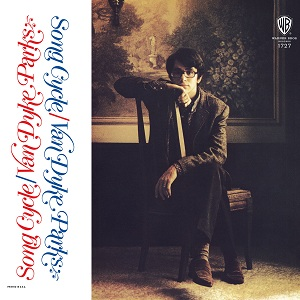

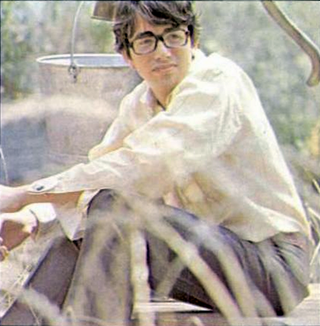

The front cover depicts a minimalist photographic portrait of Parks seated in a chair, captured by photographer Guy Webster.[94] The image is bordered by a white panel on the left containing symmetrically arranged typography displaying the album title and artist name; the reverse side includes a high-contrast black-and-white close-up of Parks alongside credits for musicians and technicians, paired with liner notes by Los Angeles Free Press journalist Paul Jay Robbins described by Henderson as "purpose-built inscrutability."[95]

The design was credited to "The Corporate Head", a collective comprising visual artists, friends, and associates, including Webster and designer Tom Wilkes, who selected the Flair italic variant of the Torino typeface for the album's typography.[96][nb 17] Webster used a large-format camera and long exposure techniques for the front cover photo, aiming to evoke a Renaissance aesthetic.[97][nb 18] The photo session took place at Parks’ residence in Fremont Place, a gated community in Hollywood where Parks lived during the album's recording.[99]

The original sleeve omitted printed lyrics, though Parks later distributed a lyric sheet upon request. Modeled after ephemeral diner menus, the sheet featured bold type, cream-toned paper, and occasional typos, intending to evoke mid-century urban vernacular. According to Henderson, "The lyrics of Song Cycle addressed the past, among other things, and did so with poignancy; the paper that they were printed on simulated a fragment of that time."[100]

Release, initial reactions, and promotion

Summarize

Perspective

So, where's the "Song"?

Warner Bros. released Song Cycle in November 1967.[101][102] Critics, particularly within the New Journalism movement, responded with favorable but often abstract analyses, including Rolling Stone contributor J. R. Young.[103] Crawdaddy! featured a cover-story review by Sandy Pearlman, who juxtaposed Parks' work with artist Marcel Duchamp's ready-made sculptures, and likened the album favorably to Muzak, a comparison echoed by his colleague Richard Meltzer.[104][nb 19] Several critics reserved praise for Parks' application of the studio as an instrument.[31] Some also suggested the album was suited for "the mystically inclined and/or the very, very high", in Henderson's description.[105] Richard Goldstein, having lauded "Donovan's Colours" in the Village Voice, subsequently compared him to George Gershwin in his New York Times review, calling it the "album we have all been waiting for: an auspicious debut, a stunning work of pop art, a vital piece of Americana, and a damned good record to boot."[106] Jim Miller's review for Rolling Stone called the album "hardly perfect, but familiarity breeds awe at what, for a first album, has been accomplished", predicting that it would influence the Beatles' next work.[107]

Ostin had a highly favorable reaction and later recalled, "We thought we had the next Beatles."[108] However, Smith struggled to market the album and was confused over its title and commercial appeal: "Intellectual critics could relate to Song Cycle, but no one else could."[109] He faced internal resistance from marketing staff and retailers, who reported widespread bafflement among record store employees.[110][nb 20] Radio programmers similarly avoided the album; despite Detroit's progressive FM station WABX championing subversive acts like the Velvet Underground and Frank Zappa's Mothers of Invention, Song Cycle received no airplay there.[112] Smith later reflected that even adventurous FM stations, then a nascent format, lacked a clear category for Parks’ work.[110] The initial advertising exacerbated the album's perceived inscrutability through hyperbolic prose and fragmented imagery, combining sections of the cover photo with text such as the following:[113]

Van Dyke Parks is generic . . . The first in a decade since Dylan and the Beatles! Already there is speculation among record critics, commentators and cognoscenti as to how and to what extent his emergence will influence tomorrow’s tastes and trends. No matter your age, musical preferences or sociological point-of-view, it is uncommonly predictable, inevitable, inescapable: You are about to become involved with Van Dyke Parks![114]

About 10,000 copies were sold within a year.[115] Concerned about initial sales, Warner Bros. launched an unconventional ad campaign spearheaded by Creative Services director Stan Cornyn, known for provocative marketing tactics.[116] For Song Cycle, he arranged a Billboard trade ad declaring "How we lost $35,509.50 [sic] on 'The Album of the Year' (Dammit)", inadvertently caricaturing Parks as an overindulgent artist by framing Warner Bros. as patrons of unprofitable art.[117][nb 21] Within these ads were review excerpts from the Los Angeles Free Press ("The most important art-rock project"), Rolling Stone ("Van Dyke Parks may come to be considered the Gertrude Stein of the new pop music"), and The Hollywood Reporter ("Very esoteric").[119] Another ad quoted a memo written by Smith: "Van Dyke's album is such a milestone, it's sailing straight into The Smithsonian Institute, completely bypassing the consumer."[114][118] Jazz & Pop praised Song Cycle as "the most important, creative and advanced pop recording since Sgt. Pepper."[115] In his June 1968 column for Esquire, Robert Christgau cautioned that Song Cycle "does not rock" and voiced "serious reservations about [Parks'] precious, overwrought lyrics and the reedy way he sings them" despite the "wonderful" music.[120]

Cornyn, who admired Parks' work, did not consult artists on promotional content, including Parks.[121] While the campaign resonated with niche audiences, it alienated mainstream listeners and incensed Parks, who reportedly accused Cornyn of attempting to destroy his career after repeating this tactic with Newman's 1968 self-titled debut album, also produced by Parks and Waronker.[122] Warner Bros. concluded Song Cycle's marketing with the "Once-In-A-Lifetime Van Dyke Parks 1¢ Sale", offering replacements for worn copies, plus an extra "to pass on to a poor but open friend", in exchange for one cent. Around 100 participants redeemed the offer, and manufacturing costs were charged to Parks’ account.[123] Cornyn later ensured that Song Cycle tracks appeared on Warner's Loss Leader samplers and mail-order compilations.[124]

According to Parks, "there was every expectation that the recording costs would be recovered, and they were, within three years."[1] His 1970 single "The Eagle and Me", a rendition of the Arlen and Harburg showtune, was later included as a bonus track on the album's Rykodisc reissue.[125]

Retrospective assessments and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

In his 2010-published 33⅓ book covering the album, Richard Henderson writes that the album's legacy has been largely eclipsed by that of the Beach Boys' unfinished Smile album, leading many "to conclude that Song Cycle was little more than ... a pale simulation of the glory that might have been SMiLE."[128] Beach Boys biographer Peter Ames Carlin reflected on the album as a challenging and often perplexing listening experience; despite owning it for decades and appreciating its ambition, he described it as demanding full attention and a departure from conventional expectations of popular music: "I found it inscrutable and—how can I put this?—an experience that was something other than fun. ... I like eccentric art. But Song Cycle threw me off time after time."[129] Barney Hoskyns decreed that Song Cycle marked the zenith of "baroque and kaleidoscopic" pop music in the 1960s, advancing "the experimentation of Smile into a completely new sphere of intellectual brilliance".[2] In 2017, Song Cycle was ranked 93 on Pitchfork's list of the finest albums of the 1960s.[130]

AllMusic reviewer Jason Ankeny described Song Cycle as an ambitious fusion of orchestral and classical influences within a pop framework. He highlighted its thematic cohesion and incorporation of diverse American musical styles—including bluegrass, ragtime, and show tunes—and characterized the "one-of-a-kind" album as a collision of historical genres with 1960s progressive sensibilities, though "occasionally overambitious and at times insufferably coy".[126] Pitchfork contributor Mike Powell, writing in a 2012 editorial, felt the album's "fussy" arrangements were its most striking quality, coupled with its "defiantly pre-rock" musical heritage: "40s lounge, big-budget film scores, early American folksong, music for bright drinks with umbrellas in them."[131]

Reviewing its 2012 Bella Union reissue, Pitchfork's Jayson Greene challenged the prevailing view that Song Cycle is "impenetrable", arguing that its accessibility depends on listeners' expectations: approaching it as a conventional singer-songwriter record would be disorienting, whereas embracing its surreal, historical pastiche—comparable to "a midnight stroll through a Civil War memorabilia museum" animated into song—reveals its idiosyncratic appeal. He recognized Parks' "peculiar" vocal delivery as "dripping with ill will", framing him as a "wiseguy pipsqueak" critiquing the grandeur he orchestrates. The lyrics' themes of artistic struggle and societal disparity, paired with Parks' ambivalence toward beauty and refinement, imbue the work with a "melancholy depth", according to Greene, who viewed this tension as central to the album's enduring resonance.[127]

Reflecting on the album, Waronker acknowledged his role in enabling Parks’ uncompromised vision, stating he chose not to obstruct Parks’ creative direction despite potential criticisms of self-indulgence.[132] He added that his own association with Song Cycle had held greater personal significance than "99% of the hit records I've been involved with."[133]

Impact and influence

Summarize

Perspective

The album's release preceded self-titled solo debuts by Newman and Ry Cooder—both co-produced by Parks and Waronker. According to Henderson, although Parks’ orchestral approach contrasted with contemporaries like Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, these works—alongside Van Morrison's Astral Weeks (1968)—collectively influenced the singer-songwriter movement of the early 1970s.[134] Brian Eno identified Song Cycle as an example of a commercially failing album that appealed exclusively to other musicians, echoing a similar well-circulated remark he had made about The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967) having inspired all its record buyers to form their own bands.[135] Henderson adds that Song Cycle galvanized "many others" to consider the studio as a compositional tool alongside "the potential of a record's production to suggest scenery and location" to an effect similar to Eno's work.[31]

Harry Nilsson, together with Newman, recorded a rendition of "Vine Street" for his 1970 album Nilsson Sings Newman.[131] Keiichi Suzuki cited Song Cycle and its Ray Bradbury-evocative sound as a key influence on his soundtracks for the Mother video game series.[136] The High Llamas' 1994 album Gideon Gaye features cover art paying homage to Song Cycle through its use of the same Torino Italic Flair typeface.[100] Joanna Newsom enlisted Parks to orchestrate her 2006 album Ys, later stating she repeatedly listened to Song Cycle during its development.[127] Newsom had immersed herself in the album after receiving a copy from musician Bill Callahan, who subsequently encouraged her to seek the collaboration with Parks.[49] Jim O'Rourke, who also contributed to Ys, ranked Song Cycle among his all-time favorite albums.[137]

Track listing

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Vine Street" (Randy Newman) | 3:40 |

| 2. | "Palm Desert" | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Widow's Walk" | 3:13 |

| 4. | "Laurel Canyon Blvd" | 0:28 |

| 5. | "The All Golden" | 3:46 |

| 6. | "Van Dyke Parks" (public domain) | 0:57 |

All tracks are written by Van Dyke Parks, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 7. | "Public Domain" | 2:34 |

| 8. | "Donovan's Colours" (Donovan Leitch) | 3:38 |

| 9. | "The Attic" | 2:56 |

| 10. | "Laurel Canyon Blvd" | 1:19 |

| 11. | "By the People" | 5:53 |

| 12. | "Pot Pourri" | 1:08 |

| Total length: | 32:39 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 13. | "The Eagle And Me" (Harold Arlen/Yip Harburg) | 2:32 |

Personnel

Summarize

Perspective

Adapted from the LP sleeve.

- Van Dyke Parks – vocals, acoustic piano, harpsichord, tack piano, electric piano, organ, Rocksichord, marimbas

Additional players

- Billie Barnum – choir

- Ron Elliott – guitar

- Gerri Engemann – choir

- Karen Gunderson – choir

- Vanessa Hendricks – choir

- Randy Newman – acoustic piano on "Vine Street"

- Durrie Parks – choir

- Gaile Parks – choir

- Julia Rinker – choir

- Paul Jay Robbins – choir

- Nik Woods – choir

- Steve Young – additional vocals

Session musicians

- Don Bagley – strings

- Gregory Bemko – strings

- Chuck Berghofer – strings

- Harry Bluestone – strings

- Samuel Boghossian – strings

- Nicolai Bolin – balalaika

- Norman Benno – woodwinds

- Arthur Briegleb – brass

- Dennis Budimir – strings

- Gary Coleman – percussion

- Vasil Crlenica – balalaika

- Vincent DeRosa – brass

- Joseph Ditullio – strings

- Jesse Ehrlich – strings

- George Fields – woodwinds

- Carl Fortina – accordion

- Nathan Gershman – strings

- Philip Goldberg – strings

- Jack Glaser – percussion

- Misha Goodatieff – strings

- Jim Gordon – drums

- William Green – woodwinds

- Hal Blaine – drums

- Jim Hendricks – additional vocals

- Jim Horn – woodwinds

- Dick Hyde – brass

- Armand Kaproff – strings

- William Kurasch – strings

- Don Lanier – guitar

- Gayle Levant – strings

- Leonard Malarsky – strings

- Virginia Majewski – strings

- Jay Migliori – woodwinds

- Tommy Morgan – woodwinds

- William Nadel – balalaika

- Ted Nash – woodwinds

- Earl Palmer – drums

- Richard Perissi – brass

- Jerome Reisler – strings

- Allan Reuss – balalaika

- Red Rhodes – strings

- Trefoni Rizzi – strings

- Lyle Ritz – strings

- Dick Rosmini – guitar

- Ralph Schaffer – strings

- Joseph Saxon – strings

- Thomas Scott – woodwinds

- Leonard Selic – strings

- Frederick Seykora – strings

- Tommy Shepard – brass

- Leon Stewart – balalaika

- Darrel Terwilliger – strings

- Tommy Tedesco – balalaika

- Bob West – strings

Technical staff

- Bruce Botnick – engineer

- Lee Herschberg – supervising engineer

- Kirby Johnson – conductor

Notes

- During the 1950s, Parks was a boarding student at the American Boychoir School in Princeton, New Jersey, where he studied voice and piano under conductors Arturo Toscanini, Thomas Beecham, and Eugene Ormandy, and performed operatic roles.[3] He later described acting as a means to fund his education: "I paid my tuition doing it, but I was only interested in music."[4]

- Parks repeatedly invoked the term "cartoon consciousness" to describe the pictorial quality of Smile embodied by Frank Holmes' original cover artwork for the album.[26]

- During mixing, Smith and Elektra founder Jac Holzman attended sessions; Holzman offered to release the album immediately, while Smith ultimately approved its distribution through Warner-Reprise. Botnick speculated that an Elektra release might have aligned with the label's psychedelic roster, but acknowledged Warner's role in Parks' subsequent career opportunities.[53]

- The technique was later adopted by other engineers, including Botnick's brother, though its most concentrated use occurred during the album's production.[62] Botnick again used the effect on the Doors' 1967 album Strange Days.[65] Henderson identified a similar effect on the piano in the Beatles' "Lovely Rita" from Sgt. Pepper.[62]

- Rhodes later gained prominence through collaborations with Michael Nesmith in the 1970s.[71]

- The same technique was later explored by minimalist composer Terry Riley and producer Lee Perry.[74]

- According to Parks, the record company "held the album for a year" until he met Jack Holzman, who "went to Warner Brothers and said, 'If you folks aren’t going to release this album, I will—how much do you want for it?'" Parks said that the label then "decided to put it out, grudgingly."[111]

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.