Mandolin

Musical instrument in the lute family From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

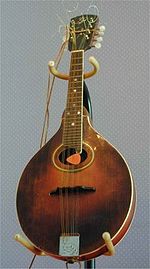

A mandolin (Italian: mandolino, pronounced [mandoˈliːno]; literally "small mandola") is a stringed musical instrument in the lute family and is generally plucked with a pick. It most commonly has four courses of doubled strings tuned in unison, thus giving a total of eight strings. A variety of string types are used, with steel strings being the most common and usually the least expensive. The courses are typically tuned in an interval of perfect fifths, with the same tuning as a violin (G3, D4, A4, E5). Also, like the violin, it is the soprano member of a family that includes the mandola, octave mandolin, mandocello and mandobass.

Archtop mandolin | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.321-6 (Neapolitan) or 321.322-6 (flat-backed) (Chordophone with permanently attached resonator and neck, sounded by a plectrum) |

| Developed | Mid-18th century from the mandolino |

| Timbre | varies with the type:

|

| Decay | fast |

| Playing range | |

(a regularly tuned mandolin with 14 frets to body) | |

| Related instruments | |

|

List

| |

| Sound sample | |

There are many styles of mandolin, but the three most common types are the Neapolitan or round-backed mandolin, the archtop mandolin and the flat-backed mandolin. The round-backed version has a deep bottom, constructed of strips of wood, glued together into a bowl. The archtop, also known as the carved-top mandolin, has an arched top and a shallower, arched back both carved out of wood. The flat-backed mandolin uses thin sheets of wood for the body, braced on the inside for strength in a similar manner to a guitar. Each style of instrument has its own sound quality and is associated with particular forms of music. Neapolitan mandolins feature prominently in European classical music and traditional music like the Andean music of Peru.[1][2][3] Archtop instruments are common in American folk music and bluegrass music. Flat-backed instruments are commonly used in Irish, British, and Brazilian folk music, and Mexican estudiantinas.

Other mandolin variations differ primarily in the number of strings and include four-string models (tuned in fifths) such as the Brescian and Cremonese; six-string types (tuned in fourths) such as the Milanese, Lombard, and Sicilian; six-course instruments of 12 strings (two strings per course) such as the Genoese; and the tricordia, with four triple-string courses (12 strings total).[4]

Much of mandolin development revolved around the soundboard (the top). Early instruments were quiet, strung with gut strings, and plucked with the fingers or with a quill. However, modern instruments are louder, using metal strings, which exert more pressure than the gut strings. The modern soundboard is designed to withstand the pressure of metal strings that would break earlier instruments. The soundboard comes in many shapes—but generally round or teardrop-shaped, sometimes with scrolls or other projections. There are usually one or more sound holes in the soundboard, either round, oval, or shaped like a calligraphic f (f-hole). A round or oval sound hole may be covered or bordered with decorative rosettes or purfling.[5][6]

History

Mandolins evolved from lutes, a family of instruments in Europe. Predecessors include the gittern and mandore or mandola in Italy during the 17th and 18th centuries. There were a variety of regional variants, but the two most widespread ones were the Neapolitan mandolin and the Lombard mandolin. The Neapolitan style has spread worldwide.

Construction

Summarize

Perspective

Mandolins have a body that acts as a resonator, attached to a neck. The resonating body may be shaped as a bowl (necked bowl lutes) or a box (necked box lutes). Traditional Italian mandolins, such as the Neapolitan mandolin, meet the necked bowl description.[8] The necked box instruments include archtop mandolins and the flatback mandolins.[9]

Strings run between mechanical tuning machines at the top of the neck to a tailpiece that anchors the other end of the strings. The strings are suspended over the neck and soundboard and pass over a floating bridge.[10][better source needed] The bridge is kept in contact with the soundboard by the downward pressure from the strings. The neck is either flat or has a slight radius, and is covered with a fingerboard with frets.[11][12][13] The action of the strings on the bridge causes the soundboard to vibrate, producing sound.[14]

Like any plucked instrument, mandolin notes decay to silence rather than sound out continuously as with a bowed note on a violin, and mandolin notes decay faster than larger chordophones like the guitar. This encourages the use of tremolo (rapid picking of one or more pairs of strings) to create sustained notes or chords. The mandolin's paired strings facilitate this technique: the plectrum (pick) strikes each of a pair of strings alternately, providing a more full and continuous sound than a single string would.

Various design variations and amplification techniques have been used to make mandolins comparable in volume with louder instruments and orchestras, including the creation of mandolin-banjo hybrids with the drum-like body of the louder banjo, adding metal resonators (most notably by Dobro and the National String Instrument Corporation) to make a resonator mandolin, and amplifying electric mandolins through amplifiers.

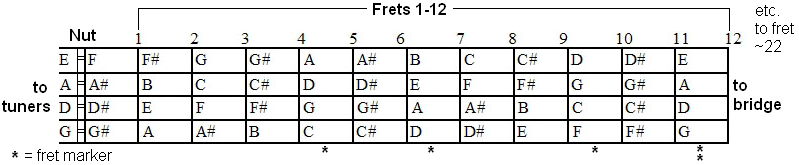

Tuning

A variety of different tunings are used. Usually, courses of 2 adjacent strings are tuned in unison. By far the most common tuning is the same as violin tuning, in scientific pitch notation G3–D4–A4–E5, or in Helmholtz pitch notation: g–d′–a′–e″.

- fourth (lowest tone) course: G3 (196.00 Hz)

- third course: D4 (293.66 Hz)

- second course: A4 (440.00 Hz; A above middle C)

- first (highest tone) course: E5 (659.25 Hz)

The numbers of Hz shown above assume a 440 Hz A, standard in most parts of the western world. Some players use an A up to 10 Hz above or below a 440, mainly outside the United States.

Other tunings exist, including cross-tunings, in which the usually doubled string runs are tuned to different pitches. Additionally, guitarists may sometimes tune a mandolin to mimic a portion of the intervals on a standard guitar tuning to achieve familiar fretting patterns.

Mandolin family

Summarize

Perspective

Soprano

The mandolin is the soprano member of the mandolin family, as the violin is the soprano member of the violin family. Like the violin, its scale length is typically about 13 inches (330 mm). Modern American mandolins modelled after Gibsons have a longer scale, about 13+7⁄8 inches (350 mm). The strings in each of its double-strung courses are tuned in unison, and the courses use the same tuning as the violin: G3–D4–A4–E5.

Piccolo

The piccolo or sopranino mandolin is a rare member of the family, tuned one octave above the mandola and one fourth above the mandolin (C4–G4–D5–A5); the same relation as that of the piccolo (to the western concert flute) or violino piccolo (to the violin and viola). One model was manufactured by the Lyon & Healy company under the Leland brand. A handful of contemporary luthiers build piccolo mandolins.

Alto

The mandola, termed the tenor mandola in Britain and Ireland and liola or alto mandolin in continental Europe, is tuned a fifth below the mandolin, in the same relationship as that of the viola to the violin. Some also call this instrument the "alto mandola". Its scale length is typically about 16+1⁄2 inches (420 mm). It is normally tuned like a viola (perfect fifth below the mandolin) and tenor banjo: C3–G3–D4–A4.

Tenor

The octave mandolin (US and Canada), termed the octave mandola in Britain and Ireland and mandola in continental Europe, is tuned an octave below the mandolin: G2–D3–A3–E4. Its relationship to the mandolin is that of the tenor violin to the violin, or the tenor saxophone to the soprano saxophone. Octave mandolin scale length is typically about 20 inches (510 mm), although instruments with scales as short as 17 inches (430 mm) or as long as 21 inches (530 mm) are not unknown.

The instrument has a variant off the coast of South America in Trinidad, where it is known as the bandol, a flat-backed instrument with four courses, the lower two strung with metal and nylon strings.[15]

Irish bouzouki played by Beth Patterson at Dublin, Ohio's Irish Fest

The Irish bouzouki, though not strictly a member of the mandolin family, has a reasonable resemblance and similar range to the octave mandolin. It derives from the Greek bouzouki (a long-necked lute), constructed like a flat-backed mandolin and uses fifth-based tunings, most often G2–D3–A3–D4. Other tunings include: A2–D3–A3–D4, G2–D3–A3–E4 (an octave below the mandolin—in which case it essentially functions as an octave mandolin), G2–D3–G3–D4 or A2–D3–A3–E4. Although the Irish bouzouki's bass course pairs are most often tuned in unison, on some instruments one of each pair is replaced with a lighter string and tuned in octaves, similar to the 12-string guitar. While occupying the same range as the octave mandolin/octave mandola, the Irish bouzouki is theoretically distinguished from the former instrument by its longer scale length, typically from 24 to 26 inches (610 to 660 mm), although scales as long as 27 inches (690 mm), which is the usual Greek bouzouki scale, are not unknown. In modern usage, however, the terms "octave mandolin" and "Irish bouzouki" are often used interchangeably to refer to the same instrument.

The modern cittern may also be loosely included in an "extended" mandolin family, based on resemblance to the flat-backed mandolins, which it predates. Its own lineage dates it back to the Renaissance. It is typically a five course (ten-string) instrument having a scale length between 20 and 22 inches (510 and 560 mm). The instrument is most often tuned to either D2–G2–D3–A3–D4 or G2–D3–A3–D4–A4, and is essentially an octave mandola with a fifth course at either the top or the bottom of its range. Some luthiers, such as Stefan Sobell, also refer to the octave mandola or a shorter-scaled Irish bouzouki as a cittern, irrespective of whether it has four or five courses.

Other relatives of the cittern, which might also be loosely linked to the mandolins (and are sometimes tuned and played as such), include the 6-course/12-string Portuguese guitar and the 5-course/9-string waldzither.

Baritone/Bass

The mandocello is classically tuned to an octave plus a fifth below the mandolin, in the same relationship as that of the cello to the violin, its strings being tuned to C2–G2–D3–A3. Its scale length is typically about 26 inches (660 mm). A typical violoncello scale is 27 inches (690 mm).

The mandolone was a Baroque member of the mandolin family in the bass range that was surpassed by the mandocello. It was part of the Neapolitan mandolin family.

The Greek laouto or laghouto (long-necked lute) is similar to a mandocello, ordinarily tuned C3/C2–G3/G2–D3/D3–A3/A3 with half of each pair of the lower two courses being tuned an octave high on a lighter gauge string. The body is a staved bowl, the saddle-less bridge glued to the flat face like most ouds and lutes, with mechanical tuners, steel strings, and tied gut frets. Modern laoutos, as played on Crete, have the entire lower course tuned to C3, a reentrant octave above the expected low C. Its scale length is typically about 28 inches (710 mm).

The Algerian mandole was developed by an Italian luthier in the early 1930s, scaled up from a mandola until it reached a scale length of approximately 25 to 27 inches.[16] It is a flatback instrument, with a wide neck and 4 courses (8 strings), 5 courses (10 strings) or 6 courses (12 strings), and is used in Algeria and Morocco. The instrument can be tuned as a guitar, oud, or mandocello, depending on the music it will be used to play and player preference. When tuning it as a guitar the strings will be tuned (E2) (E2) A2 A2 D3 D3 G3 G3 B3 B3 (E4) (E4);[17] strings in parentheses are dropped for a five- or four-course instrument. Using a common Arabic oud tuning D2 D2 G2 G2 A2 A2 D3 D3 (G3) (G3) (C4) (C4).[18] For a mandocello tuning using fifths C2 C2 G2 G2 D3 D3 A3 A3 (E4) (E4).[19]

Mandobass

The mandobass is the bass version of the mandolin, just as the double bass is the bass to the violin. Like the double bass, it most frequently has 4 single strings, rather than double courses—and like the double bass, it is most commonly tuned to perfect fourths rather than fifths like most mandolin family instruments: E1–A1–D2–G2,—the same tuning as a bass guitar. These were made by the Gibson company in the early 20th century, was also never very common. A smaller scale four-string mandobass, usually tuned in fifths: G1–D2–A2–E3 (two octaves below the mandolin), though not as resonant as the larger instrument, was often preferred by players as easier to handle and more portable.[20] Reportedly, however, most mandolin orchestras preferred to use the ordinary double bass, rather than a specialised mandolin family instrument. Calace and other Italian makers predating Gibson also made mandolin-basses.

The relatively rare eight-string mandobass, or "tremolo-bass", also exists, with double courses like the rest of the mandolin family, and is tuned either G1–D2–A2–E3, two octaves lower than the mandolin, or C1–G1–D2–A2, two octaves below the mandola.[21][22]

Variations

Summarize

Perspective

Bowlback

Bowlback mandolins (also known as roundbacks), are used worldwide. They are most commonly manufactured in Europe, where the long history of mandolin development has created local styles. However, Japanese luthiers also make them.

Owing to the shape and to the common construction from wood strips of alternating colors, in the United States these are sometimes colloquially referred to as the "potato bug", "potato beetle", or tater-bug mandolin.[23]

Neapolitan and Roman styles

The Neapolitan style has an almond-shaped body resembling a bowl, constructed from curved strips of wood. It usually has a bent sound table, canted in two planes with the design to take the tension of the eight metal strings arranged in four courses. A hardwood fingerboard sits on top of or is flush with the sound table. Very old instruments may use wooden tuning pegs, while newer instruments tend to use geared metal tuners. The bridge is a movable length of hardwood. A pickguard is glued below the sound hole under the strings.[24][25][26] European roundbacks commonly use a 13-inch (330 mm) scale instead of the 13+7⁄8 inches (350 mm) common on archtop Mandolins.[27]

Intertwined with the Neapolitan style is the Roman style mandolin, which has influenced it.[28] The Roman mandolin had a fingerboard that was more curved and narrow.[28] The fingerboard was lengthened over the sound hole for the E strings, the high pitched strings.[28] The shape of the back of the neck was different, less rounded with an edge, the bridge was curved making the G strings higher.[28] The Roman mandolin had mechanical tuning gears before the Neapolitan.[28]

Manufacturers of Neapolitan-style mandolins

Martin mandolins and harp mandolin on display at the Martin Guitar Factory

Prominent Italian manufacturers include Vinaccia (Naples), Embergher[29] (Rome) and Calace (Naples).[30] Other modern manufacturers include Lorenzo Lippi (Milan), Hendrik van den Broek (Netherlands), Brian Dean (Canada), Salvatore Masiello and Michele Caiazza (La Bottega del Mandolino) and Ferrara, Gabriele Pandini.[27]

In the United States, when the bowlback was being made in numbers, Lyon and Healy was a major manufacturer, especially under the "Washburn" brand.[30] Other American manufacturers include Martin, Vega, and Larson Brothers.[30]

In Canada, Brian Dean has manufactured instruments in Neapolitan, Roman, German and American styles[31] but is also known for his original 'Grand Concert' design created for American virtuoso Joseph Brent.[32]

German manufacturers include Albert & Mueller, Dietrich, Klaus Knorr, Reinhold Seiffert and Alfred Woll.[27][30] The German bowlbacks use a style developed by Seiffert, with a larger and rounder body.[27]

Japanese brands include Kunishima and Suzuki.[33] Other Japanese manufacturers include Oona, Kawada, Noguchi, Toichiro Ishikawa, Rokutaro Nakade, Otiai Tadao, Yoshihiko Takusari, Nokuti Makoto, Watanabe, Kanou Kadama and Ochiai.[27][34]

Other bowlback styles

Cremonese mandolin with four strings, from an 1805 book by Bartolomeo Bortolazzi

Lombard mandolin with twelve strings in six courses. The bridge is glued to the soundboard, like a guitar's bridge.

Giovanni Vailati, "Blind mandolinist of Cremona", toured Europe in the 1850s with a six-string Lombard mandolin.[35]

Another family of bowlback mandolins came from Milan and Lombardy.[36] These mandolins are closer to the mandolino or mandore than other modern mandolins.[36] They are shorter and wider than the standard Neapolitan mandolin, with a shallow back.[37] The instruments have 6 strings, 3 wire treble-strings and 3 gut or wire-wrapped-silk bass-strings.[36][37] The strings ran between the tuning pegs and a bridge that was glued to the soundboard, as a guitar's. The Lombard mandolins were tuned g–b–e′–a′–d″–g″ (shown in Helmholtz pitch notation).[37] A developer of the Milanese style was Antonio Monzino (Milan) and his family who made them for six generations.[36]

Samuel Adelstein described the Lombard mandolin in 1893 as wider and shorter than the Neapolitan mandolin, with a shallower back and a shorter and wider neck, with six single strings to the regular mandolin's set of 4.[38] The Lombard was tuned C–D–A–E–B–G.[38] The strings were fastened to the bridge like a guitar's.[38] There were 20 frets, covering three octaves, with an additional 5 notes.[38] When Adelstein wrote, there were no nylon strings, and the gut and single strings "do not vibrate so clearly and sweetly as the double steel string of the Neapolitan."[38]

Brescian mandolin or Cremonese mandolin

Brescian mandolins (also known as Cremonese) that have survived in museums have four gut strings instead of six and a fixed bridge.[39][40] The mandolin was tuned in fifths, like the Neapolitan mandolin.[39] In his 1805 mandolin method, Anweisung die Mandoline von selbst zu erlernen nebst einigen Uebungsstucken von Bortolazzi, Bartolomeo Bortolazzi popularised the Cremonese mandolin, which had four single-strings and a fixed bridge, to which the strings were attached.[41][40] Bortolazzi said in this book that the new wire-strung mandolins were uncomfortable to play, when compared with the gut-string instruments.[41] Also, he felt they had a "less pleasing...hard, zither-like tone" as compared to the gut string's "softer, full-singing tone."[41] He favored the four single strings of the Cremonese instrument, which were tuned the same as the Neapolitan.[40][41]

Genoese mandolin, a blend of styles

Like the Lombard mandolin, the Genoese mandolin was not tuned in fifths. Its 6 gut strings (or 6 courses of strings) were tuned as a guitar but one octave higher: e-a-d’-g’-b natural-e”.[42][43] Like the Neapolitan and unlike the Lombard mandolin, the Genoese does not have the bridge glued to the soundboard, but holds the bridge on with downward tension, from strings that run between the bottom and neck of the instrument. The neck was wider than the Neapolitan mandolin's neck.[42] The peg-head is similar to the guitar's.[43]

Archtop

At the very end of the 19th century, a new style, with a carved top and back construction inspired by violin family instruments began to supplant the European-style bowl-back instruments in the United States. This new style is credited to mandolins designed and built by Orville Gibson, a Kalamazoo, Michigan, luthier who founded the "Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Co., Limited" in 1902. Gibson mandolins evolved into two basic styles: the Florentine or F-style, which has a decorative scroll near the neck, two points on the lower body and usually a scroll carved into the headstock; and the A-style, which is pear-shaped, has no points and usually has a simpler headstock.

These styles generally have either two f-shaped soundholes like a violin (F-5 and A-5), or a single oval sound hole (F-4 and A-4 and lower models) directly under the strings. Much variation exists between makers working from these archetypes, and other variants have become increasingly common. Generally, in the United States, Gibson F-hole F-5 mandolins and mandolins influenced by that design are strongly associated with bluegrass, while the A-style is associated with other types of music, although it too is most often used for and associated with bluegrass. The F-5's more complicated woodwork also translates into a more expensive instrument.

Internal bracing to support the top in the F-style mandolins is usually achieved with parallel tone bars, similar to the bass bar on a violin. Some makers instead employ "X-bracing", which is two tone-bars mortised together to form an X. Some luthiers now using a "modified x-bracing" that incorporates both a tone bar and X-bracing.

Numerous modern mandolin makers build instruments that largely replicate the Gibson F-5 Artist models built in the early 1920s under the supervision of Gibson acoustician Lloyd Loar. Original Loar-signed instruments are sought after and extremely valuable. Other makers from the Loar period and earlier include Lyon and Healy, Vega and Larson Brothers.

Pressed archtops

The ideal for archtops has been solid pieces of wood carved into the right shape. However, another archtop exists, the top made of laminated wood or thin sheets of solid wood, pressed into the arched shape. These have become increasingly common in the world of internationally constructed musical instruments in the 21st century.

Pressed-top instruments are made to appear the same as carved-top instruments but do not sound the same as carved-wood tops. Carved-wood tops when carved to the ideal thickness, produce the sound consumers expect. Not carving them correctly dulls the sound. The sound of a carved-wood instrument changes the longer it is played, and older instruments are sought out for their rich sound.

Laminated-wood presstops are less resonant than carved wood, the wood and glue vibrating differently than wood grain. Presstops made of solid wood have the wood's natural grain compressed, typically creating a sound that is less full than a well-made, carved-top mandolin.

Flatback

Flatback mandolins use a thin sheet of wood with bracing for the back, as a guitar uses, rather than the bowl of the bowlback or the arched back of the carved mandolins.

Like the bowlback, the flatback has a round sound hole. This has been sometimes modified to an elongated hole, called a D-hole. The body has a rounded almond shape with flat or sometimes canted soundboard.[44]

The type was developed in Europe in the 1850s.[44] The French and Germans called it a Portuguese mandolin, although they also developed it locally.[44] The Germans used it in Wandervogel.[45]

The bandolim is commonly used wherever the Spanish and Portuguese took it: in South America, in Brazil (Choro) and in the Philippines.[45]

In the early 1970s English luthier Stefan Sobell developed a large-bodied, flat-backed mandolin with a carved soundboard, based on his own cittern design; this is often called a 'Celtic' mandolin.[46][47]

American forms include the Army-Navy mandolin, the flatiron and the pancake mandolins.

Tone

The tone of the flatback is described as warm or mellow, suitable for folk music and smaller audiences. The instrument sound does not punch through the other players' sound like a carved top does.

Double top, double back

The double top is a feature that luthiers are experimenting with in the 21st century, to get better sound.[48] However, mandolinists and luthiers have been experimenting with them since at least the early 1900s.

Back in the early 1900s, mandolinist Ginislao Paris approached Luigi Embergher to build custom mandolins.[49] The sticker inside one of the four surviving instruments indicates the build was called after him, the Sistema Ginislao Paris).[49] Paris' round-back double-top mandolins use a false back below the soundboard to create a second hollow space within the instrument.[49]

Modern mandolinists such as Joseph Brent and Avi Avital use instruments customized, either by the luthier's choice or at the request of the player.[48][50] Joseph Brent's mandolin, made by Brian Dean also uses what Brent calls a false back.[51] Brent's mandolin was the luthier's solution to Brent's request for a loud mandolin in which the wood was clearly audible, with less metallic sound from the strings.[48] The type used by Avital is variation of the flatback, with a double top that encloses a resonating chamber, sound holes on the side, and a convex back.[52] It is made by one manufacturer in Israel, luthier Arik Kerman.[53] Other players of Kerman mandolins include Alon Sariel,[54][55] Jacob Reuven,[53] and Tom Cohen.[56]

Others

Mandolinetto

Other American-made variants include the mandolinetto or Howe-Orme guitar-shaped mandolin (manufactured by the Elias Howe Company between 1897 and roughly 1920), which featured a cylindrical bulge along the top from fingerboard end to tailpiece and the Vega mando-lute (more commonly called a cylinder-back mandolin manufactured by the Vega Company between 1913 and roughly 1927), which had a similar longitudinal bulge but on the back rather than the front of the instrument.

Mandolin-banjo

An instrument with a mandolin neck paired with a banjo-style body was patented by Benjamin Bradbury of Brooklyn in 1882 and given the name banjolin by John Farris in 1885.[57] Today banjolin is sometimes reserved to describe an instrument with four strings, while the version with the four courses of double strings is called a mandolin-banjo.

Resonator mandolin

A resonator mandolin or "resophonic mandolin" is a mandolin whose sound is produced by one or more metal cones (resonators) instead of the customary wooden soundboard (mandolin top/face). Historic brands include Dobro and National.

Electric mandolin

As with almost every other contemporary chordophone, another modern variant is the electric mandolin. These mandolins can have four or five individual or double courses of strings. They were developed in the early 1930s, contemporaneous with the development of the electric guitar. They come in solid body and acoustic electric forms.

Specific instruments have been designed to overcome the mandolin's rapid decay with its plucked notes.[58] Fender released a model in 1992 with an additional string (a high A, above the E string), a tremolo bridge and extra humbucker pickup (total of two).[58] The result was an instrument capable of playing heavy metal style guitar riffs or violin-like passages with sustained notes that can be adjusted as with an electric guitar.[58]

Playing traditions worldwide

Summarize

Perspective

The international repertoire of music for mandolin is almost unlimited, and musicians use it to play various types of music. This is especially true of violin music, since the mandolin has the same tuning as the violin. Following its invention and early development in Italy the mandolin spread throughout the European continent. The instrument was primarily used in a classical tradition with Mandolin orchestras, so-called Estudiantinas or in Germany Zupforchestern appearing in many cities. Following this continental popularity of the mandolin family local traditions appeared outside Europe in the Americas and in Japan. Travelling mandolin virtuosi like Carlo Curti, Giuseppe Pettine, Raffaele Calace and Silvio Ranieri contributed to the mandolin becoming a "fad" instrument in the early 20th century.[59] This "mandolin craze" was fading by the 1930s, but just as this practice was falling into disuse, the mandolin found a new niche in American country, old-time music, bluegrass and folk music. More recently, the Baroque and Classical mandolin repertory and styles have benefited from the raised awareness of and interest in Early music, with media attention to classical players such as Israeli Avi Avital, Italian Carlo Aonzo, and American Joseph Brent. In India, the mandolin is played in classical Carnatic music. The musician U. Srinivas was perhaps the greatest mandolin player in this style.[60] Lauded across the world for his virtuosity with the instrument, he died young.[61]

Notable literature

Summarize

Perspective

Art or "classical" music

The tradition of so-called "classical music" for the mandolin has been somewhat spotty, due to its being widely perceived as a "folk" instrument. Significant composers did write music specifically for the mandolin, but few large works were composed for it by the most widely regarded composers. The total number of these works is rather small in comparison to—say—those composed for violin. One result of this dearth being that there were few positions for mandolinists in regular orchestras. To fill this gap in the literature, mandolin orchestras have traditionally played many arrangements of music written for regular orchestras or other ensembles. Some players have sought out contemporary composers to solicit new works.

Furthermore, of the works that have been written for mandolin from the 18th century onward, many have been lost or forgotten. Some of these await discovery in museums and libraries and archives. One example of rediscovered 18th-century music for mandolin and ensembles with mandolins is the Gimo collection, collected in the first half of 1762 by Jean Lefebure.[62] Lefebure collected the music in Italy, and it was forgotten until manuscripts were rediscovered.[62]

Vivaldi created some concertos for mandolinos and orchestra: one for 4-chord mandolino, string bass & continuo in C major, (RV 425), and one for two 5-chord mandolinos, bass strings & continuo in G major, (RV 532), and concerto for two mandolins, 2 violons "in Tromba"—2 flûtes à bec, 2 salmoe, 2 théorbes, violoncelle, cordes et basse continuein in C major (p. 16).

Beethoven composed mandolin music[63] and enjoyed playing the mandolin.[64] His 4 small pieces date from 1796: Sonatine WoO 43a; Adagio ma non troppo WoO 43b; Sonatine WoO 44a and Andante con Variazioni WoO 44b.

The opera Don Giovanni by Mozart (1787) includes mandolin parts, including the accompaniment to the famous aria Deh vieni alla finestra, and Verdi's opera Otello calls for guzla accompaniment in the aria Dove guardi splendono raggi, but the part is commonly performed on mandolin.[65]

Gustav Mahler used the mandolin in his Symphony No. 7, Symphony No. 8 and Das Lied von der Erde.

Parts for mandolin are included in works by Schoenberg (Variations Op. 31), Stravinsky (Agon), Prokofiev (Romeo and Juliet) and Webern (opus Parts 10)

Some 20th-century composers also used the mandolin as their instrument of choice (amongst these are: Schoenberg, Webern, Stravinsky and Prokofiev).

Among the most important European mandolin composers of the 20th century are Raffaele Calace (composer, performer and luthier) and Giuseppe Anedda (virtuoso concert pianist and professor of the first chair of the Conservatory of Italian Mandolin, Padua, 1975). Today representatives of Italian classical music and Italian classical-contemporary music include Ugo Orlandi, Carlo Aonzo, Dorina Frati, Mauro Squillante and Duilio Galfetti.

Japanese composers also produced orchestral music for mandolin in the 20th century, but these are not well known outside Japan. Notable composers include Morishige Takei and Yasuo Kuwahara.[66]

Traditional mandolin orchestras remain especially popular in Japan and Germany, but also exist throughout the United States, Europe and the rest of the world. They perform works composed for mandolin family instruments, or re-orchestrations of traditional pieces. The structure of a contemporary traditional mandolin orchestra consists of: first and second mandolins, mandolas (either octave mandolas, tuned an octave below the mandolin, or tenor mandolas, tuned like the viola), mandocellos (tuned like the cello), and bass instruments (conventional string bass or, rarely, mandobasses). Smaller ensembles, such as quartets composed of two mandolins, mandola, and mandocello, may also be found.

Unaccompanied solo

- Minuet

- John Peterson

- Moving Fast Through Autumn Light (2000)

- The Three Names Of Shiva (1992)

- Variations on a Theme by Haydn

- Song of summer

- Cadenza No.1

- Cadenza No.2

- Cadenza No.3

- Cadenza No.4

- Cadenza No.5

- Cadenza No.6

- Cadenza No.7

- Cadenza No.8

- Cadenza No.10

- Cadenza No.11

- Prelude No. 1

- Prelude No. 2

- Prelude No. 3

- Prelude No. 5

- Prelude No. 10

- Prelude No. 11

- Prelude No. 14

- Prelude No. 15

- Large prelude

- Collard

- Sylvia

- Minuet of rose

- Heinrich Koniettsuni

- Partita No. 1, etc.

- Sonatine, etc.

- Sense – structure

- The Gray Wolf

- Perpetuum Mobile

- Variations from Der Fluyten Lust-hof

- Sakutarō Hagiwara

- Hataoriru maiden

- Takei Shusei

- Spring to go

- Seiichi Suzuki

- Variations on Schubert lullaby

- City of Elm

- Variations on Kojonotsuki of subject matter

- Two Episodes for solo mandolin

- "Spring has come" Variations

- Prayer

- Fantasia second No.

- Serenata

- Beautiful my child and where

- Prayer of the evening

- Variations on September Affair of the subject matter

- Makino YukariTaka

- Spring snow of ballads

- In early spring

- Takashi Kubota

- Nocturne

- Etude

- Fantasia first No.

- Moon and mountain witch

- Impromptu

- Winter Light

- Mukyu motion

- Jon-gara

- Silent door

Accompaniment with solo

- Sonatine in C minor, WoO 43a

- Adagio in E♭ major WoO 43b

- Sonatine in C major WoO 44a

- Andante and Variations in D major WoO 44b

- Dioces aztecas

- The Legend of Princess Noccalula

- 4 Quartet for Mandolin, Violin, Viola, and Lute

- 4 Divertimenti for Mandolin, Violin & B.c.

- Sonata in C major Op. 35

- Spanish Capriccio

- Mazurka for concert

- Waltz for concert

- Bizaria

- Aria Varia data

- Mandolin Concerto No. 1

- Mandolin Concerto No. 1

- Mandolin Concerto No. 2

- Mukyu motion

- Tarantella

- Song of Nostalgia

- Elegy

- Mazurka for concert

- Warsaw of memories

- Enrico Marcelli

- Gypsy style Capriccio

- Fantastic Waltz

- Mukyu motion

- Polonaise for concert

- Divertimento for mandolin and harp

- Such as a duo for the mandolin and guitar

- Norbert Shupuronguru

- Serenade for mandolin and guitar

- Franco Marugora

- Grand Sonata for mandolin and guitar

- Slovenia wind Dances such as

- Sonatine

- Light of silence

- Rikuya Terashima

- Sonata for mandolin and piano (2002)[67]

Duo and musical ensemble

A duet or duo is a musical composition for two performers in which the performers have equal importance to the piece. A musical ensemble with more than two solo instruments or voices is called trio, quartet, quintet, sextet, septet, octet, etc.

- Ella Von Adajewska-Schultz (1846–1926)

- Venezuelan Serenade[68]

- Valentine Abt (1873–1942)

- In Venice Waters[68]

- Chants Des Gondoliers[68]

- Duo

- Sonata in D major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo[68]

- Ignazio Bitelli (c. 1880–1956)

- L'Albero di Natale, pastorale for mandolin & guitar[68]

- Il Gondoliere, valse for 2 mandolins & guitar[68]

- Costantino Bertucci

- Il Carnevale Di Venezia Con Variazioni[68]

- Pietro Gaetano Boni (1686–1741)

- Sonate pour mandoline en la, Op. 2 n° 1[68]

- Sonate pour mandoline en ré mineur, Op. 2 n° 2

- Sonate pour mandoline en ré, Op. 2 n° 9[68]

- Antonio Del Buono

- "In Gondola" Serenata Veneziana "Ai Mandolnisti Di Venezia[68]

- Sinfonia for 2 Mandolins & Continuo, (Gimo 76)[69]

- Au Fil De L'Eau[68]

- Charon Crossing the Styx (mandolin & double bass)

- Four Whimsies (mandolin & octave mandolin)

- Les gravures de Gustave Doré (mandolin & guitar)

- Six Pantomimes for Two Mandolins

- Sonatina No. 3 for Mandolin & Violin

- Op. 59a Sonatina for 2 mandolins (1952)

- Hooperisms Op.181 (1991)

- Barbara and Deborah Op.175 (1990)

- Three Mandolin Duets Op.282 (2005)

- Paul and Adrian Op.165(1989)

- Giovani Battista Gervasio

- Sonata for Mandolin & Continuo (Gimo 141)[69][70]

- Sonata per camera (Gimo 143)[69][70]

- Sinfonia for 2 Mandolins & Continuo, (Gimo 149)[69][70]

- Trio for 2 Mandolins & Continuo, (Gimo 150)[69][70]

- Sonata in D major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo[68]

- Sonata in G major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo[68]

- Giuseppe Giuliano

- Sonata in D major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo

- Geoffrey Gordon

- Interiors of a Courtyard (mandolin & guitar)

- Addiego Guerra

- Sonata in G major for Mandolin and Basso Continuo

- Positive Hattori

- Concerto for two mandolin and piano

- Mandolin Canons (mandolin & guitar)

- 3 Duets for Mandolin and Violin

- Serenade for Viola and Mandolin

- Tyler Kaier

- Den lille Havfrue (mandolin & guitar)

- Mit den Augen eines Falken for mandolin & guitar (2016)

- Giovanni Battista Maldura

- Barcarola Veneziana Di Mendelssohn[68]

- Edward Mezzacapo (1832–1898)

- Le Chant Du Gondolier[68]

- Heinrich Molbe (1835–1915)

- Gondolata Op. 74 Per Mandolino, Clarinetto E Pianoforte[68]

- Carlo Munier (1859–1911)

- Medaka, revolving lantern

- John Peterson

- Wired Life (1999)

- Giuseppe Pettine (1874–1966)

- Barcarola Per Mandolino[68]

- Du edge Martino

- Sonata in D minor (K77)

- Sonata in E minor (K81)

- Sonata in G minor (K88)

- Sonata No. 54 (K. 89) in D minor for Mandolin and Basso Continuo

- Sonata in D minor (K89)

- Sonata in D minor (K90)

- Sonata in G (K91)

- Silent Light for mandolin & harpsichord (2001)

- Two Pieces for Two Mandolins (2002)

- Sergeij Taneev (1856–1913)

- Venezia Di Notte, Barcarola Op. 9 No. 1[68]

- Serenata Per Voce, Mandolino E Pianoforte Op. 9 No. 2 Alla Contessa Tat'jana L'vovna Tolstaja[68]

- Roberto Valentini (1674–1747)

- Sonate pour mandoline en la, Op. 12 n° 1

- Sonate pour mandoline en ré mineur, Op. 12 n° 2

- Sonate pour mandoline en sol, Op. 12 n° 3

- Sonate pour mandoline en sol mineur, Op. 12 n° 4

- Sonate pour mandoline en mi mineur, Op. 12 n° 5

- Sonate pour mandoline en ré, Op. 12 n° 6

Concerto

Concerto: a musical composition generally composed of three movements, in which, usually, one solo instrument (for instance, a piano, violin, cello or flute) is accompanied by an orchestra or concert band.

- Three Sisters, for mandolin and chamber orchestra

- Concerto for Mandolin and Chamber Orchestra Op.141 (1984)

- Concerto No. 2 Op.151 (1986)

- Zohar, Sephardic Concerto (1998)

- The Spirit's Lay Concerto for Mandolin and Orchestra (2000)

- Caroline Szeto

- Concerto For Mandolin and Chamber Orchestra (1998)

- Concerto for Mandolin and Orchestra in D Major

- Mandolin Concerto in C major,

- Concerto for two mandolinos in G major

- Concerto for two mandolinos, 2 violons " in Tromba"—2 flûtes à bec, 2 salmoe, 2 théorbes, violoncelle, cordes et basse continuein in C major

- Francisco Rodrigo Arto (Venezuela)

- Mandolin Concerto (1984)[71]

- Dominico Caudioso

- Mandolin Concerto in G Major

- Mandolin Concerto No. 1 in D Minor

- Mandolin Concerto No. 2 in D Major

- Mandolin Concerto No. 3 in E Minor

- Mandolin Concerto No. 4 in G Major

- Concerto for Two Mandolins ("Rromane Bjavela")

- Gerardo Enrique Dirié (Argentina)

- Los ocho puentes for four recorders, mandolin and percussion (1984)[72]

- Mandolin Concerto in G major

- Concerto for piano, mandolin, trumpet and double bass in E♭ major

- Mandolin Concerto in B♭ major

- Mandolin Concerto in E♭ major

- Mandolin Concerto in C major

- Mandolin Concerto in G major

- Mandolin Concerto in G major

- Armin Kaufmann

- Mandolin Concerto

- Dietrich Erdmann

- Mandolin Concerto

- Mandolin and the Concerto for Strings

- Brian Israel (1951–1986)

- Concerto for Mandolin (1985)

- Sonatinetta (1984)

- Surrealistic Serenade (1985)

- Makino YukariTaka

- Mandolin Concerto

- Mandolin and the Concerto for Strings

- Tanaka Ken

- "Arc" for mandolin and orchestra

- Vladimir Kororutsuku

- Suite "positive and negative"

- Mandolin Concerto

- "Nedudim" ("Wanderings") Fantasia-Concertante for mandolin and string orchestra (2014)

Mandolin in the orchestra

Orchestral works in which the mandolin has a limited part.

- Opera La finta parigina

- Opera The Curious Affair of the Count of Monte Blotto

- Concerto for orchestra 25 Concertos Comiques: Concerto nr 24 in C major "La Marche du Huron"

- Symphony No. 2 "Symphony Of Chorales" (1958)

- L'Amant jaloux (Paris, 1778)[73]

- Oratorio Alexander Balus

- Opera Le Grand Macabre

- Opera Don Perlimplin, ovvero il trionfo dell'amore e dell'immaginazione

- Opera Don Giovanni[73]

- Opera Halewijn

- Romance sans paroles

- Symphony No. 2

- Symphony No. 3

- Ballet music Romeo and Juliet

- Symphonic poem Festivals of Rome

- Ballet music Anna Karenina

- Opera A Basso Porto: Intermezzo for mandolins and orchestra

- Ballet music Agon

- Opera Otello

- Oratorio Juditha triumphans

- Five Pieces for Orchestra

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.