Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Robot Operating System

Set of software frameworks for robot software development From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Robot Operating System (ROS or ros) is an open-source robotics middleware suite. Although ROS is not an operating system (OS) but a set of software frameworks for robot software development, it provides services designed for a heterogeneous computer cluster such as hardware abstraction, low-level device control, implementation of commonly used functionality, message-passing between processes, and package management. Running sets of ROS-based processes are represented in a graph architecture where processing takes place in nodes that may receive, post, and multiplex sensor data, control, state, planning, actuator, and other messages. Despite the importance of reactivity and low latency in robot control, ROS is not a real-time operating system (RTOS). However, it is possible to integrate ROS with real-time computing code.[3] The lack of support for real-time systems has been addressed in the creation of ROS 2,[4][5][6] a major revision of the ROS API which will take advantage of modern libraries and technologies for core ROS functions and add support for real-time code and embedded system hardware.

Remove ads

Software in the ROS Ecosystem[7] can be separated into three groups:

- language- and platform-independent tools used for building and distributing ROS-based software;

- ROS client library implementations such as roscpp,[8] rospy,[9] and roslisp;[10]

- packages containing application-related code that uses one or more ROS client libraries.[11]

Both the language-independent tools and the main client libraries (C++, Python, and Lisp) are released under the terms of the BSD license, and as such are open-source software and free for both commercial and research use. The majority of other packages are licensed under a variety of open-source licenses. These other packages implement commonly used functionality and applications such as hardware drivers, robot models, datatypes, planning, perception, simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), simulation tools, and other algorithms.

The main ROS client libraries are geared toward a Unix-like system, mostly because of their dependence on large sets of open-source software dependencies. For these client libraries, Ubuntu Linux is listed as "Supported" while other variants such as Fedora Linux, macOS, and Microsoft Windows are designated "experimental" and are supported by the community.[12] The native Java ROS client library, rosjava,[13] however, does not share these limitations and has enabled ROS-based software to be written for the Android OS.[14] rosjava has also enabled ROS to be integrated into an officially supported MATLAB toolbox which can be used on Linux, macOS, and Microsoft Windows.[15] A JavaScript client library, roslibjs[16] has also been developed which enables integration of software into a ROS system via any standards-compliant web browser.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Early days at Stanford (2007 and earlier)

Sometime before 2007, the first pieces of what eventually would become ROS began coalescing at Stanford University.[17][18] Eric Berger and Keenan Wyrobek, PhD students working in Kenneth Salisbury's[19] The Robotics laboratory at Stanford, was leading the Personal Robotics Program.[20] While working on robots to do manipulation tasks in human environments, the two students noticed that many of their colleagues were held back by the diverse nature of robotics: an excellent software developer might not have the hardware knowledge required, someone developing state of the art path planning might not know how to do the computer vision required. In an attempt to remedy this situation, the two students set out to make a baseline system that would provide a starting place for others in academia to build upon. In the words of Eric Berger, "something that didn’t suck, in all of those different dimensions".[17]

In their first steps towards this unifying system, the two built the PR1 as a hardware prototype and began to work on software from it, borrowing the best practices from other early open-source robotic software frameworks, particularly switchyard, a system that Morgan Quigley, another Stanford PhD student, had been working on in support of the STanford Artificial Intelligence Robot (STAIR)[21][22][23][24] by the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Early funding of US$50,000 was provided by Joanna Hoffman and Alain Rossmann, which supported the development of the PR1. While seeking funding for further development,[25] Eric Berger and Keenan Wyrobek met Scott Hassan, the founder of Willow Garage, a technology incubator which was working on an autonomous SUV and a solar autonomous boat. Hassan shared Berger and Wyrobek's vision of a "Linux for robotics", and invited them to come and work at Willow Garage. Willow Garage was started in January 2007, and the first commit of ROS code was made to SourceForge on 7 November 2007.[26]

Willow Garage (2007–2013)

Willow Garage began developing the PR2 robot as a follow-up to the PR1, and ROS as the software to run it. Groups from more than twenty institutions made contributions to ROS, both the core software and the growing number of packages that worked with ROS to form a greater software ecosystem.[27][28] That people outside of Willow were contributing to ROS (especially from Stanford's STAIR project) meant that ROS was a multi-robot platform from the start. While Willow Garage had originally had other projects in progress, they were scrapped in favor of the Personal Robotics Program: which focused on producing the PR2 as a research platform for academia and ROS as the open-source robotics stack that would underlie both academic research and tech startups, much like the LAMP stack did for web-based startups.

In December 2008, Willow Garage met the first of its three internal milestones: continuous navigation for the PR2 over two days and a distance of pi kilometers.[29] Soon after, an early version of ROS (0.4 Mango Tango)[30] was released, followed by the first RVIZ documentation and the first paper on ROS.[28] In early summer, the second internal milestone: having the PR2 navigate the office, open doors, and plug itself it in, was reached.[31] This was followed in August by the initiation of the ROS.org website.[32] Early tutorials on ROS were posted in December,[33] preparing for the release of ROS 1.0, in January 2010.[34] This was Milestone 3: producing tons of documentation and tutorials for the enormous abilities that Willow Garage's engineers had developed over the preceding 3 years.

Following this, Willow Garage achieved one of its longest-held goals: giving away 10 PR2 robots to worthy academic institutions. This had long been a goal of the founders, as they felt that the PR2 could kick-start robotics research around the world. They ended up awarding eleven PR2s to different institutions, including University of Freiburg (Germany), Robert Bosch GmbH, Georgia Institute of Technology, KU Leuven (Belgium), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Stanford University, Technical University of Munich (Germany), University of California, Berkeley, University of Pennsylvania, University of Southern California (USC), and University of Tokyo (Japan).[35] This, combined with Willow Garage's highly successful internship program[36] (run from 2008 to 2010 by Melonee Wise), helped to spread the word about ROS throughout the robotics world. The first official ROS distribution release: ROS Box Turtle, was released on 2 March 2010, marking the first time that ROS was officially distributed with a set of versioned packages for public use. These developments led to the first drone running ROS,[37] the first autonomous car running ROS,[38] and the adaption of ROS for Lego Mindstorms.[39] With the PR2 Beta program well underway, the PR2 robot was officially released for commercial purchase on 9 September 2010.[40]

2011 was a banner year for ROS with the launch of ROS Answers, a Q/A forum for ROS users, on 15 February;[41] the introduction of the highly successful TurtleBot robot kit on 18 April;[42] and the total number of ROS repositories passing 100 on 5 May.[43] Willow Garage began 2012 by creating the Open Source Robotics Foundation (OSRF)[44] in April. The OSRF was immediately awarded a software contract by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).[45] Later that year, the first ROSCon was held in St. Paul, Minnesota,[46] the first book on ROS, ROS By Example,[47] was published, and Baxter, the first commercial robot to run ROS, was announced by Rethink Robotics.[48] Soon after passing its fifth anniversary in November, ROS began running on every continent on 3 December 2012.[49]

In February 2013, the OSRF became the primary software maintainers for ROS,[50] foreshadowing the announcement in August that Willow Garage would be absorbed by its founders, Suitable Technologies.[51] At this point, ROS had released seven major versions (up to ROS Groovy),[52] and had users all over the globe. This chapter of ROS development would be finalized when Clearpath Robotics took over support responsibilities for PR2 in early 2014.[53]

OSRF and Open Robotics (2013–present)

In the years since OSRF took over the primary development of ROS, a new version has been released every year,[52] while interest in ROS continues to grow. ROSCons have occurred every year since 2012, co-located with either ICRA or IROS, two flagship robotics conferences. Meetups of ROS developers have been organized in a variety of countries,[54][55][56] a number of ROS books have been published,[57] and many educational programs initiated.[58][59] On 1 September 2014, NASA announced the first robot to run ROS in space: Robotnaut 2, on the International Space Station.[60] In 2017, the OSRF changed its name to Open Robotics. Tech giants Amazon and Microsoft began to take an interest in ROS during this time, with Microsoft porting core ROS to Windows in September 2018,[61] followed by Amazon Web Services releasing RoboMaker in November 2018.[62]

Perhaps the most important development of the OSRF/Open Robotics years thus far (not to discount the explosion of robot platforms that began to support ROS or the enormous improvements in each ROS version) was the proposal of ROS 2, a significant API change to ROS which is intended to support real-time programming, a wider variety of computing environments, and more modern technology.[63] ROS 2 was announced at ROSCon 2014,[64] the first commits to the ros2 repository were made in February 2015, followed by alpha releases in August 2015.[65] The first distribution release of ROS 2, Ardent Apalone, was released on 8 December 2017,[65] ushering in a new era of next-generation ROS development.

Remove ads

Design

Summarize

Perspective

Philosophy

ROS was designed to be open source, intending that users would be able to choose the configuration of tools and libraries that interacted with the core of ROS so that users could shift their software stacks to fit their robot and application area. As such, there is very little which is core to ROS, beyond the general structure within which programs must exist and communicate. In one sense, ROS is the underlying plumbing behind nodes and message passing. However, in reality, ROS is not only plumbing, but a rich and mature set of tools, a wide-ranging set of robot-agnostic abilities provided by packages, and a greater ecosystem of additions to ROS.

Computation graph model

ROS processes are represented as nodes in a graph structure, connected by edges called topics.[66] ROS nodes can pass messages to one another through topics, make service calls to other nodes, provide a service for other nodes, or set or retrieve shared data from a communal database called the parameter server. A process called the ROS1 Master[66] makes all of this possible by registering nodes to themselves, setting up node-to-node communication for topics, and controlling parameter server updates. Messages and service calls do not pass through the master, rather the master sets up peer-to-peer communication between all node processes after they register themselves with the master. This decentralized architecture lends itself well to robots, which often consist of a subset of networked computer hardware, and may communicate with off-board computers for heavy computing or commands.

Nodes

A node represents one process running the ROS graph. Every node has a name, which registers with the ROS1 master before it can take any other actions. Multiple nodes with different names can exist under different namespaces, or a node can be defined as anonymous, in which case it will randomly generate an additional identifier to add to its given name. Nodes are at the center of ROS programming, as most ROS client code is in the form of a ROS node which takes actions based on information received from other nodes, sends information to other nodes, or sends and receives requests for actions to and from other nodes.

Topics

Topics are named buses over which nodes send and receive messages.[67] Topic names must be unique within their namespace as well. To send messages to a topic, a node must publish to said topic, while to receive messages it must subscribe. The publish/subscribe model is anonymous: no node knows which nodes are sending or receiving on a topic, only that it is sending/receiving on that topic. The types of messages passed on a topic vary widely and can be user-defined. The content of these messages can be sensor data, motor control commands, state information, actuator commands, or anything else.

Services

A node may also advertise services.[68] A service represents an action that a node can take which will have a single result. As such, services are often used for actions that have a defined start and end, such as capturing a one-frame image, rather than processing velocity commands to a wheel motor or odometer data from a wheel encoder. Nodes advertise services and call services from one another.

Parameter server

The parameter server[68] is a database shared between nodes which allows for communal access to static or semi-static information. Data that does not change frequently and as such will be infrequently accessed, such as the distance between two fixed points in the environment, or the weight of the robot, are good candidates for storage in the parameter server.

Remove ads

Tools

Summarize

Perspective

ROS's core functionality is augmented by a variety of tools that allow developers to visualize and record data, easily navigate the ROS package structures, and create scripts automating complex configuration and setup processes. The addition of these tools greatly increases the abilities of systems using ROS by simplifying and providing solutions to several common robotics development problems. These tools are provided in packages like any other algorithm, but rather than providing implementations of hardware drivers or algorithms for various robotic tasks, these packages provide task and robot-agnostic tools that come with the core of most modern ROS installations.

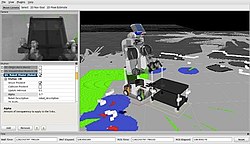

rviz

rviz[69] (Robot Visualization tool) is a three-dimensional visualizer used to visualize robots, the environments they work in, and sensor data. It is a highly configurable tool, with many different types of visualizations and plugins. Unified Robot Description Format (URDF) is an XML file format for robot model description.

rosbag

rosbag[70] is a command line tool used to record and playback ROS message data. rosbag uses a file format called bags,[71] which log ROS messages by listening to topics and recording messages as they come in. Playing messages back from a bag is largely the same as having the original nodes that produced the data in the ROS computation graph, making bags a useful tool for recording data to be used in later development. While rosbag is a command line only tool, rqt_bag[72] provides a GUI interface to rosbag.

catkin

catkin[73] is the ROS build system, having replaced rosbuild[74] as of ROS Groovy. catkin is based on CMake and is similarly cross-platform, open-source, and language-independent.

rosbash

The rosbash[75] package provides a suite of tools which augment the functionality of the bash shell. These tools include rosls, roscd, and roscp, which replicate the functionalities of ls, cd, and cp respectively. The ROS versions of these tools allow users to use ros package names in place of the file path where the package is located. The package also adds tab-completion to most ROS utilities and includes rosed, which edits a given file with the chosen default text editor, as well rosrun, which runs executables in ROS packages. rosbash supports the same functionalities for zsh and tcsh, to a lesser extent.

roslaunch

roslaunch[76] is a tool used to launch multiple ROS nodes both locally and remotely, as well as setting parameters on the ROS parameter server. roslaunch configuration files, which are written using XML can easily automate a complex startup and configuration process into a single command. roslaunch scripts can include other roslaunch scripts, launch nodes on specific machines, and even restart processes that die during execution.

Remove ads

Packages of note

Summarize

Perspective

ROS contains many open-source implementations of common robotics functionality and algorithms. These open-source implementations are organized into packages. Many packages are included as part of ROS distributions, while others may be developed by individuals and distributed through code-sharing sites such as github. Some packages of note include:

Systems and tools

Mapping and localization

- slam toolbox[80] provides full 2D SLAM and localization system.

- gmapping[81] provides a wrapper for OpenSlam's Gmapping algorithm for simultaneous localization and mapping.

- cartographer[82] provides real time 2D and 3D SLAM algorithms developed at Google.

- amcl[83] provides an implementation of adaptive Monte-Carlo localization.

Navigation

- navigation[84] provides the capability of navigating a mobile robot in a planar environment.

Manipulation

- MoveIt![85] provides motion planning capabilities for robot manipulators. Its default planning library is the Open Motion Planning Library (OMPL).[86]

Perception

Coordinate frame representation

Simulation

Remove ads

Versions and releases

Summarize

Perspective

ROS releases may be incompatible with other releases and are often referred to by code name rather than version number. ROS 2 currently releases a version every year in May, following the release of Ubuntu LTS versions.[92][93] These releases are alternating supported for 5 years (even years/LTS Ubuntu version release) and 1.5 years (uneven years/no LTS Ubuntu version release). ROS 1 does not see any new version. Aside from this, there has been the ROS-Industrial or ROS-I derivate project since at least 2012.

ROS 1

ROS 2

ROS-Industrial

ROS-Industrial[109] is an open-source project (BSD (legacy)/Apache 2.0 (preferred) license) that extends the advanced abilities of ROS to manufacturing automation and robotics. In the industrial environment, there are two different approaches to programming a robot: either through an external proprietary controller, typically implemented using ROS, or via the respective native programming language of the robot. ROS can therefore be seen as the software-based approach to programming industrial robots instead of the classic robot controller-based approach.

The ROS-Industrial repository includes interfaces for common industrial manipulators, grippers, sensors, and device networks. It also provides software libraries for automatic 2D/3D sensor calibration, process path/motion planning, applications like Scan-N-Plan, developer tools like the Qt Creator ROS Plugin, and training curricula that are specific to the needs of manufacturers. ROS-I is supported by an international Consortium of industry and research members. The project began as a collaborative endeavor between Yaskawa Motoman Robotics, Southwest Research Institute, and Willow Garage to support the use of ROS for manufacturing automation, with the GitHub repository being founded in January 2012 by Shaun Edwards (SwRI). Currently, the Consortium is divided into three groups; the ROS-Industrial Consortium Americas (led by SwRI and located in San Antonio, Texas), the ROS-Industrial Consortium Europe (led by Fraunhofer IPA and located in Stuttgart, Germany), and the ROS-Industrial Consortium Asia Pacific (led by Advanced Remanufacturing and Technology Centre (ARTC) and Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and located in Singapore).

The Consortia supports the global ROS-Industrial community by conducting ROS-I training, providing technical support and setting the future roadmap for ROS-I, as well as conducting pre-competitive joint industry projects to develop new ROS-I abilities.[110]

Space ROS

In November 2020, NASA announced Blue Origin had been selected through the Space Technology Mission Directorate’s Announcement of Collaboration Opportunity (ACO) to co-develop Space Robot Operating System (Space ROS) together with three NASA centers.[111] The purpose of Space ROS is to provide a reusable and modular software framework for robotic and autonomous space systems predicated on ROS 2 that is compliant to aerospace mission and safety assurance requirements (such as NPR 7150.2 and DO-178C). The project was formulated and led by Will Chambers,[112] Blue Origin's principal technologist of robotics at the time. In 2021, Blue Origin subcontracted software development workload to Open Robotics who remained on the team until the program ended in 2022. Space ROS is currently an open community project.[113][114] PickNik Robotics and Open Source Robotics Foundation currently lead the Space ROS effort.[115]

Remove ads

ROS-compatible robots and hardware

Robots

- ABB, Adept, Fanuc, Motoman, and Universal Robots are supported by ROS-Industrial.[116]

- Baxter[117] at Rethink Robotics, Inc.

- CK-9: robotics development kit by Centauri Robotics, supports ROS.[118]

- GoPiGo3: Raspberry Pi-based educational robot, supports ROS.[119]

- HERB[120] developed at Carnegie Mellon University in Intel's personal robotics program

- Husky A200: robot developed (and integrated into ROS) by Clearpath Robotics[121]

- Nao[122] humanoid: University of Freiburg's Humanoid Robots Lab[123] developed a ROS integration for the Nao humanoid based on an initial port by Brown University[124][125]

- PR1: personal robot developed in Ken Salisbury's lab at Stanford[126]

- PR2: personal robot being developed at Willow Garage[127]

- Raven II Surgical Robotic Research Platform[128][129]

- ROSbot: autonomous robot platform by Husarion[130]

- Shadow Robot Hand:[131] a fully dexterous humanoid hand.

- STAIR I and II:[132] robots developed in Andrew Ng's lab at Stanford

- Stretch: an integrated mobile manipulator by Hello Robot targeting assistive applications.[133][134]

- SummitXL:[135] mobile robot developed by Robotnik, an engineering company specialized in mobile robots, robotic arms, and industrial solutions with ROS architecture.

- UBR1:[136][137] developed by Unbounded Robotics, a spin-off of Willow Garage.

- Webots: robot simulator integrating a complete ROS programming interface.[138]

SBCs and hardware

- BeagleBoard: the robotics lab of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium[139] has ported ROS to the Beagleboard.

- Raspberry Pi: image of Ubuntu Mate with ROS[140] by Ubiquity Robotics; installation guide for Raspbian;[141] Installation guide for ROS2 to Raspberry Pi.[142]

- Sitara ARM Processors have support for the ROS package as part of the official Linux SDK.[143]

Remove ads

See also

References

Related projects

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads