Proto-Slavic language

Proto-language of all the Slavic languages From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium BC through the 6th century AD.[1] As with most other proto-languages, no attested writings have been found; scholars have reconstructed the language by applying the comparative method to all the attested Slavic languages and by taking into account other Indo-European languages.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2021) |

| Proto-Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Common Slavic, Common Slavonic | |

| Reconstruction of | Slavic languages |

| Region | Eastern and Central Europe |

| Era | 2nd m. BC – 6th c. AD |

Reconstructed ancestors | |

Rapid development of Slavic speech occurred during the Proto-Slavic period, coinciding with the massive expansion of the Slavic-speaking area. Dialectal differentiation occurred early on during this period, but overall linguistic unity and mutual intelligibility continued for several centuries, into the 10th century or later. During this period, many sound changes diffused across the entire area, often uniformly. This makes it inconvenient to maintain the traditional definition of a proto-language as the latest reconstructable common ancestor of a language group, with no dialectal differentiation. (This would necessitate treating all pan-Slavic changes after the 6th century or so as part of the separate histories of the various daughter languages.) Instead, Slavicists typically handle the entire period of dialectally differentiated linguistic unity as Common Slavic.

One can divide the Proto-Slavic/Common Slavic time of linguistic unity roughly into three periods:

- an early period with little or no dialectal variation

- a middle period of slight-to-moderate dialectal variation

- a late period of significant variation

Authorities differ as to which periods should be included in Proto-Slavic and in Common Slavic. The language described in this article generally reflects the middle period, usually termed Late Proto-Slavic (sometimes Middle Common Slavic[2]) and often dated to around the 7th to 8th centuries. This language remains largely unattested, but a late-period variant, representing the late 9th-century dialect spoken around Thessaloniki (Solun) in Macedonia, is attested in Old Church Slavonic manuscripts.

Introduction

Summarize

Perspective

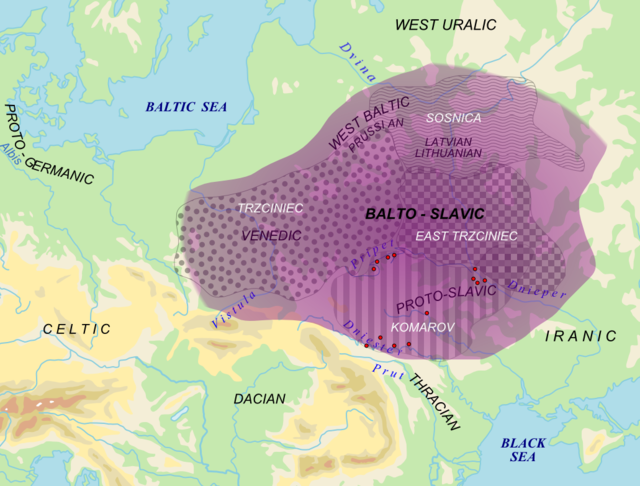

Proto-Slavic is descended from the Proto-Balto-Slavic branch of the Proto-Indo-European language family, which is also the ancestor of the Baltic languages, e.g. Lithuanian and Latvian. Proto-Slavic gradually evolved into the various Slavic languages during the latter half of the first millennium AD, concurrent with the explosive growth of the Slavic-speaking area. There is no scholarly consensus concerning either the number of stages involved in the development of the language (its periodization) or the terms used to describe them.

One division is made up of three periods:[1]

- Early Proto-Slavic (until 1000 BC)

- Middle Proto-Slavic (1000 BC – 1 AD)

- Late Proto-Slavic (1–600 AD)

Another division is made up of four periods:[citation needed]

- Pre-Slavic (c. 1500 BC – 300 AD): A long, stable period of gradual development. The most significant phonological developments during this period involved the prosodic system, e.g. tonal and other register distinctions on syllables.

- Early Common Slavic or simply Early Slavic (c. 300–600): The early, uniform stage of Common Slavic, but also the beginning of a longer period of rapid phonological change. As there are no dialectal distinctions reconstructible from this period or earlier, this is the period for which a single common ancestor (that is, "Proto-Slavic proper") can be reconstructed.

- Middle Common Slavic (c. 600–800): The stage with the earliest identifiable dialectal distinctions. Rapid phonological change continued, alongside the massive expansion of the Slavic-speaking area. Although some dialectal variation did exist, most sound changes were still uniform and consistent in their application. By the end of this stage, the vowel and consonant phonemes of the language were largely the same as those still found in the modern languages. For this reason, reconstructed "Proto-Slavic" forms commonly found in scholarly works and etymological dictionaries normally correspond to this period.

- Late Common Slavic (c. 800–1000, although perhaps through c. 1150 in Kievan Rus', in the far northeast): The last stage in which the whole Slavic-speaking area still functioned as a single language, with sound changes normally propagating throughout the entire area, although often with significant dialectal variation in the details.

This article considers primarily Middle Common Slavic, noting when there is slight dialectal variation. It also covers Late Common Slavic when there are significant developments that are shared (more or less) identically among all Slavic languages.

Notation

Summarize

Perspective

Vowel notation

Two different and conflicting systems for denoting vowels are commonly in use in Indo-European and Balto-Slavic linguistics on the one hand, and Slavic linguistics on the other. In the first, vowel length is consistently distinguished with a macron above the letter, while in the latter it is not clearly indicated. The following table explains these differences:

For consistency, all discussions of words in Early Slavic and before (the boundary corresponding roughly to the monophthongization of diphthongs, and the Slavic second palatalization) use the common Balto-Slavic notation of vowels. Discussions of Middle and Late Common Slavic, as well as later dialects, use the Slavic notation.

Other vowel and consonant diacritics

- The caron on consonants ⟨č ď ľ ň ř š ť ž⟩ is used in this article to denote the consonants that result from iotation (coalescence with a /j/ that previously followed the consonant) and the Slavic first palatalization. This use is based on the Czech alphabet, and is shared by most Slavic languages and linguistic explanations about Slavic.

- The acute accent on the consonant ⟨ś⟩ indicates a special, more frontal "hissing" sound. The acute is used in several other Slavic languages (such as Polish, Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian) to denote a similar "frontal" quality to a consonant.

- The ogonek ⟨ę ǫ⟩, indicates vowel nasalization.

Prosodic notation

For Middle and Late Common Slavic, the following marks are used to indicate tone and length distinctions on vowels, based on the standard notation in Serbo-Croatian:

- Acute accent ⟨á⟩: A long rising accent, originating from the Balto-Slavic "acute" accent. This occurred in the Middle Common Slavic period and earlier.

- Grave accent ⟨à⟩: A short rising accent. It occurred from Late Common Slavic onwards, and developed from the shortening of the original acute (long rising) tone.

- Inverted breve ⟨ȃ⟩: A long falling accent, originating from the Balto-Slavic "circumflex" accent. In Late Common Slavic, originally short (falling) vowels were lengthened in monosyllables under some circumstances, and are also written with this mark. This secondary circumflex occurs only on the original short vowels e, o, ь, ъ in an open syllable (i.e. when not forming part of a liquid diphthong).

- Double grave accent ⟨ȁ⟩: A short falling accent. It corresponds to the Balto-Slavic "short" accent. All short vowels that were not followed by a sonorant consonant originally carried this accent, until some were lengthened (see preceding item).

- Tilde ⟨ã⟩: Usually a long rising accent. This indicates the Late Common Slavic "neoacute" accent, which was usually long, but short when occurring on some syllables types in certain languages. It resulted from retraction of the accent (movement towards an earlier syllable) under certain circumstances, often when the Middle Common Slavic accent fell on a word-final final yer (*ь/ĭ or *ъ/ŭ).

- Macron ⟨ā⟩: A long vowel with no distinctive tone. In Middle Common Slavic, vowel length was an implicit part of the vowel (*e, *o, *ь, *ъ are inherently short, all others are inherently long), so this is usually redundant for Middle Common Slavic words. However, it became distinctive in Late Common Slavic after several shortenings and lengthenings had occurred.

Other prosodic diacritics

There are multiple competing systems used to indicate prosody in different Balto-Slavic languages. The most important for this article are:

- Three-way system of Proto-Slavic, Proto-Balto-Slavic, modern Lithuanian: Acute tone ⟨á⟩, circumflex tone ⟨ȃ⟩ or ⟨ã⟩, short accent ⟨à⟩.

- Four-way Serbo-Croatian system, also used in Slovenian and often in Slavic reconstructions: long rising ⟨á⟩, short rising ⟨à⟩, long falling ⟨ȃ⟩, short falling ⟨ȁ⟩. In the Chakavian dialect and other archaic dialects, the long rising accent is notated with a tilde ⟨ã⟩, indicating its normal origin in the Late Common Slavic neoacute accent (see above).

- Length only, as in Czech and Slovak: long ⟨á⟩, short ⟨a⟩.

- Stress only, as in Ukrainian, Russian and Bulgarian: stressed ⟨á⟩, unstressed ⟨a⟩.

History

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

The following is an overview of the phonemes that are reconstructible for Middle Common Slavic.

Vowels

Middle Common Slavic had the following vowel system (IPA symbol where different):

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The columns marked "central" and "back" may alternatively be interpreted as "back unrounded" and "back rounded" respectively, but rounding of back vowels was distinctive only between the vowels *y and *u. The other back vowels had optional non-distinctive rounding. The vowels described as "short" and "long" were simultaneously distinguished by length and quality in Middle Common Slavic, although some authors prefer the terms "lax" and "tense" instead.[3] Many modern Slavic languages have since lost all length distinctions.

Vowel length evolved as follows:

- In the Early Slavic period, length was the primary distinction (as indicated, for example, by Greek transcriptions of Slavic words[citation needed], or early loanwords from Slavic into the Finnic languages).

- In the Middle Common Slavic period, all long/short vowel pairs also assumed distinct qualities, as indicated above.

- During the Late Common Slavic period, various lengthenings and shortenings occurred, creating new long counterparts of originally short vowels, and short counterparts of originally long vowels (e.g. long *o, short *a). The short close vowels *ь/ĭ and *ъ/ŭ were either lost or lowered to mid vowels, leaving the originally long high vowels *i, *y and *u with non-distinctive length. As a result, vowel quality became the primary distinction among the vowels, while length became conditioned by accent and other properties and was not a lexical property inherent in each vowel.

In § Grammar below, additional distinctions are made in the reconstructed vowels:

- The distinction between *ě₁ and *ě₂ is based on etymology and they have different effects on a preceding consonant: *ě₁ triggers the first palatalization and then becomes *a, while *ě₂ triggers the second palatalization and does not change.

- *ę̇ represents the phoneme that must be reconstructed as the outcome of pre-Slavic *uN, *ūN after a palatal consonant. This vowel has a different outcome from "regular" *ę in many languages: it denasalises to *ě in West and East Slavic, but merges with *ę in South Slavic. It is explained in more detail at History of Proto-Slavic § Nasalization.

Consonants

Middle Common Slavic had the following consonants (IPA symbols where different):[4]

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ň (ɲ ~ nʲ) | ||

| Plosive | v− | *p | *t | *ť (cː) | *k |

| v+ | *b | *d | *ď (ɟː) | *g | |

| Affricate | v− | *c (t͡s) | *č (t͡ʃ) | ||

| v+ | *dz | {*dž} (d͡ʒ) | |||

| Fricative | v− | *s | *š {*ś} (ʃ) | *x | |

| v+ | *z | *ž (ʒ) | |||

| Trill | *r | *ř (rʲ) | |||

| Lateral approximant | *l | *ľ (ʎ ~ lʲ) | |||

| Central approximant | *v | *j | |||

The phonetic value (IPA symbol) of most consonants is the same as their traditional spelling. Some notes and exceptions:

- *c denotes a voiceless alveolar affricate [t͡s]. *dz was its voiced counterpart [d͡z].

- *š and *ž were postalveolar [ʃ] and [ʒ].

- *č and *dž were postalveolar affricates, [t͡ʃ] and [d͡ʒ], although the latter only occurred in the combination *ždž and had developed into *ž elsewhere.

- The pronunciation of *ť and *ď is not precisely known, though it is likely that they were held longer (geminate). They may have been palatalized dentals [tʲː dʲː], or perhaps true palatal [cː ɟː] as in modern Macedonian.

- The exact value of *ś is also unknown but usually presumed to be [ɕ] or [sʲ]. It was rare, only occurring before front vowels from the second palatalization of *x, and it merged with *š in West Slavic and *s in the other branches.

- *v was a labial approximant [ʋ] originating from an earlier [w]. It may have had bilabial [w] as an allophone in certain positions (as in modern Slovene and Ukrainian).

- *l was [l]. Before back vowels, it was probably fairly strongly velarized [ɫ] in many dialects.

- The sonorants *ľ *ň could have been either palatalized [lʲ nʲ] or true palatal [ʎ ɲ].

- The pronunciation of *ř is not precisely known, but it was approximately a palatalized trill [rʲ]. In all daughter languages except Slovenian it either merged with *r (Southwest Slavic) or with the palatalized *rʲ resulting from *r before front vowels (elsewhere). The resulting *rʲ merged back into *r in some languages, but remained distinct in Czech (becoming a fricative trill, denoted ⟨ř⟩ in spelling), in Old Polish (it subsequently merged with *ž ⟨ż⟩ but continues to be spelled ⟨rz⟩, although some dialects have kept a distinction to this day, specially among the elderly[5]), in Russian (except when preceding a consonant), and in Bulgarian (when preceding a vowel).

In most dialects, non-distinctive palatalization was probably present on all consonants that occurred before front vowels. When the high front yer *ь/ĭ was lost in many words, it left this palatalization as a "residue", which then became distinctive, producing a phonemic distinction between palatalized and non-palatalized alveolars and labials. In the process, the palatal sonorants *ľ *ň *ř merged with alveolar *l *n *r before front vowels, with both becoming *lʲ *nʲ *rʲ. Subsequently, some palatalized consonants lost their palatalization in some environments, merging with their non-palatal counterparts. This happened the least in Russian and the most in Czech. Palatalized consonants never developed in Southwest Slavic (modern Croatian, Serbian, and Slovenian), and the merger of *ľ *ň *ř with *l *n *r did not happen before front vowels (although Serbian and Croatian later merged *ř with *r).

Pitch accent

As in its ancestors, Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Indo-European, one syllable of each Common Slavic word was accented (carried more prominence). The placement of the accent was free and thus phonemic; it could occur on any syllable and its placement was inherently a part of the word. The accent could also be either mobile or fixed, meaning that inflected forms of a word could have the accent on different syllables depending on the ending, or always on the same syllable.

Common Slavic vowels also had a pitch accent. In Middle Common Slavic, all accented long vowels, nasal vowels and liquid diphthongs had a distinction between two pitch accents, traditionally called "acute" and "circumflex" accent. The acute accent was pronounced with rising intonation, while the circumflex accent had a falling intonation. Short vowels (*e *o *ь *ъ) had no pitch distinction, and were always pronounced with falling intonation. Unaccented (unstressed) vowels never had tonal distinctions, but could still have length distinctions. These rules are similar to the restrictions that apply to the pitch accent in Slovene.

In the Late Common Slavic period, several sound changes occurred. Long vowels bearing the acute (long rising) accent were usually shortened, resulting in a short rising intonation. Some short vowels were lengthened, creating new long falling vowels. A third type of pitch accent developed, known as the "neoacute", as a result of sound laws that retracted the accent (moved it to the preceding syllable). This occurred at a time when the Slavic-speaking area was already dialectally differentiated, and usually syllables with the acute and/or circumflex accent were shortened around the same time. Hence it is unclear whether there was ever a period in any dialect when there were three phonemically distinct pitch accents on long vowels. Nevertheless, taken together, these changes significantly altered the distribution of the pitch accents and vowel length, to the point that by the end of the Late Common Slavic period almost any vowel could be short or long, and almost any accented vowel could have falling or rising pitch.

Phonotactics

Most syllables in Middle Common Slavic were open. The only closed syllables were those that ended in a liquid (*l or *r), forming liquid diphthongs, and in such syllables, the preceding vowel had to be short. Consonant clusters were permitted, but only at the beginning of a syllable. Such a cluster was syllabified with the cluster entirely in the following syllable, contrary to the syllabification rules that are known to apply to most languages. For example, *bogatьstvo "wealth" was divided into syllables as *bo-ga-tь-stvo, with the whole cluster *-stv- at the beginning of the syllable.

By the beginning of the Late Common Slavic period, all or nearly all syllables had become open as a result of developments in the liquid diphthongs. Syllables with liquid diphthongs beginning with *o or *e had been converted into open syllables, for example *TorT became *TroT, *TraT or *ToroT in the various daughter languages. The main exception are the Northern Lechitic languages (Kashubian, extinct Slovincian and Polabian) only with lengthening of the syllable and no metathesis (*TarT, e.g. PSl. gordъ > Kashubian gard; > Polabian *gard > gord). In West Slavic and South Slavic, liquid diphthongs beginning with *ь or *ъ had likewise been converted into open syllables by converting the following liquid into a syllabic sonorant (palatal or non-palatal according to whether *ь or *ъ preceded respectively).[6] This left no closed syllables at all in these languages. Most of the South Slavic languages, as well as Czech and Slovak, tended to preserve the syllabic sonorants, but in the Lechitic languages (such as Polish) and Bulgarian, they fell apart again into vowel-consonant or consonant-vowel combinations. In East Slavic, the liquid diphthongs in *ь or *ъ may have likewise become syllabic sonorants, but if so, the change was soon reversed, suggesting that it may never have happened in the first place.

Grammar

Summarize

Perspective

Proto-Slavic retained several of the grammatical categories inherited from Proto-Indo-European, especially in nominals (nouns and adjectives). Seven of the eight Indo-European cases had been retained (nominative, accusative, locative, genitive, dative, instrumental, vocative). The ablative had merged with the genitive. It also retained full use of the singular, dual and plural numbers, and still maintained a distinction between masculine, feminine and neuter gender. However, verbs had become much more simplified, but displayed their own unique innovations.

Alternations

As a result of the three palatalizations and the fronting of vowels before palatal consonants, both consonant and vowel alternations were frequent in paradigms, as well as in word derivation.

The following table lists various consonant alternations that occurred in Proto-Slavic, as a result of various suffixes or endings being attached to stems:

- ^1 Originally formed a diphthong with the preceding vowel, which then became a long monophthong.

- ^2 Forms a nasal vowel.

- ^3 Forms a liquid diphthong.

Vowels were fronted when following a palatal or "soft" consonant (*j, any iotated consonant, or a consonant that had been affected by the progressive palatalization). Because of this, most vowels occurred in pairs, depending on the preceding consonant.

| Origin | a | e | i | u | ā | ē | ī | ū | an | en | in | un | ūn | au | ai | ei | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After hard consonants | o | e | ь | ъ | a | ě₁ | i | y | ǫ | ę | ę, ь | ǫ, ъ | y | u | ě₂ | i | |||

| After soft consonants | e | ь | a | i | ǫ | ę | ę, ь | ę̇, ь | ę̇ | u | i | ||||||||

- The distinction between *ě₁ and *ě₂ is based on etymology and have different effects on a preceding consonant: *ě₁ triggers the first palatalization and then becomes *a, while *ě₂ triggers the second palatalization and does not change.

- Word-final *-un and *-in lost nasal and became *-u and *-i rather than forming a nasal vowel, so that nasal vowels formed medially only. This explains the double reflex.

- The distinction between *ę and *ę̇ is based on their presumed origin and *ę̇ has a different outcome from "regular" *ę in many languages: it denasalises to *ě in West and East Slavic, but merges with *ę in South Slavic. (It is explained in more detail at History of Proto-Slavic#Nasalization.)

- *ā and *an apparently did not take part in the fronting of back vowels, or in any case the effect was not visible. Both have the same reflex regardless of the preceding consonant.

Most word stems therefore became classed as either "soft" or "hard", depending on whether their endings used soft (fronted) vowels or the original hard vowels. Hard stems displayed consonant alternations before endings with front vowels as a result of the two regressive palatalizations and iotation.

As part of its Indo-European heritage, Proto-Slavic also retained ablaut alternations, although these had been reduced to unproductive relics. The following table lists the combinations (vowel softening may alter the outcomes).

| PIE | e | ey | ew | el | er | em | en |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long ē-grade | ě₁ | ? | ? | ? | ? | ę | |

| e-grade | e | i | ju | el | er | ę | |

| zero grade | ? | ь | ъ | ьl, ъl | ьr, ъr | ę, ǫ | |

| o-grade | o | ě₂ | u | ol | or | ǫ | |

| Long ō-grade | a | ? | ? | ? | ? | ǫ | |

Although qualitative alternations (e-grade versus o-grade versus zero grade) were no longer productive, the Balto-Slavic languages had innovated a new kind of ablaut, in which length was the primary distinction. This created two new alternation patterns, which did not exist in PIE: short *e, *o, *ь, *ъ versus long *ě, *a, *i, *y. This type of alternation may have still been productive in Proto-Slavic, as a way to form imperfective verbs from perfective ones.

Accent classes

Originally in Balto-Slavic, there were only two accent classes, fixed (with fixed stem accent) and mobile (with accent alternating between stem and ending). There was no class with fixed accent on the ending. Both classes originally had both acute and circumflex stems in them. Two sound changes acted to modify this basic system:

- Meillet's law, which removed any stem acutes in mobile-accent words.

- Dybo's law, which advanced the accent in non-acute fixed-accent words.

As a result, three basic accent paradigms emerged:[7][8][9]

- Accent paradigm a, with a fixed accent on the stem (either on the root or on a morphological suffix).

- Accent paradigm b, with largely fixed accent on the first syllable of the ending, sometimes retracted back onto the stem by Ivšić's law.

- Accent paradigm c ("mobile"), with alternation of the accent between the first syllable of the stem and the ending, depending on the paradigmatic form.

For this purpose, the "stem" includes any morphological suffixes (e.g. a diminutive suffix), but not generally on the inflectional suffix that indicates the word class (e.g. the -ā- of feminine ā-stem nouns), which is considered part of the ending. Verbs also had three accent paradigms, with similar characteristics to the corresponding noun classes. However, the situation is somewhat more complicated due to the large number of verb stem classes and the numerous forms in verbal paradigms.

Due to the way in which the accent classes arose, there are certain restrictions:

- In AP a, the accented syllable always had the acute tone, and therefore was always long, because short syllables did not have tonal distinctions. Thus, single-syllable words with an originally short vowel (*e, *o, *ь, *ъ) in the stem could not belong to accent AP a. If the stem was multisyllabic, the accent could potentially fall on any stem syllable (e.g. *ję̄zū́k- "tongue"). These restrictions were caused by Dybo's law, which moved the accent one syllable to the right, but only in originally barytonic (stem-accented) nominals that did not have acute accent in the stem. AP a thus consists of the "leftover" words that Dybo's law did not affect.

- In AP b, the stem syllable(s) could be either short or long.

- In AP c, in forms where the accent fell on the stem and not the ending, that syllable was either circumflex or short accented, never acute accented. This is due to Meillet's law, which converted an acute accent to a circumflex accent if it fell on the stem in AP c nominals. Thus, Dybo's law did not affect nouns with a mobile accent paradigm. This is unlike Lithuanian, where Leskien's law (a law similar to Dybo's law) split both fixed and mobile paradigms in the same way, creating four classes.

- Consequently, circumflex or short accent on the first syllable could only occur in AP c. In AP a, it did not occur by definition, while in AP b, the accent always shifted forward by Dybo's law.

Some nouns (especially jā-stem nouns) fit into the AP a paradigm but have neoacute accent on the stem, which can have either a short or a long syllable. A standard example is *võľa "will", with neoacute accent on a short syllable. These nouns earlier belonged to AP b; as a result, grammars may treat them as belonging either to AP a or b.

During the Late Common Slavic period, the AP b paradigm became mobile as a result of a complex series of changes that moved the accent leftward in certain circumstances, producing a neoacute accent on the newly stressed syllable. The paradigms below reflect these changes. All languages subsequently simplified the AP b paradigms to varying degrees; the older situation can often only be seen in certain nouns in certain languages, or indirectly by way of features such as the Slovene neo-circumflex tone that carry echoes of the time when this tone developed.

Nouns

Most of the Proto-Indo-European declensional classes were retained. Some, such as u-stems and masculine i-stems, were gradually falling out of use and being replaced by other, more productive classes.

The following tables are examples of Proto-Slavic noun-class paradigms, based on Verweij (1994). There were many changes in accentuation during the Common Slavic period, and there are significant differences in the views of different scholars on how these changes proceeded. As a result, these paradigms do not necessarily reflect a consensus. The view expressed below is that of the Leiden school, following Frederik Kortlandt, whose views are somewhat controversial and not accepted by all scholars.

AP a nouns

| Masc. long -o | Nt. long -o | Masc. long -jo | Fem. long -ā | Fem. long -jā | Masc. long -i | Fem. long -i | Masc. long -u | Fem. long -ū | Fem. long -r | Masc. long -n | Nt. long -n | Nt. long -s | Nt. long -nt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bread | summer | cry | wound | storm | son-in-law | thread | clay | pumpkin | mother | stone | seed | miracle | lamb | ||

| Singular | Nom | xlě̀bъ | lě̀to | plàčь | ràna | bùřā | zę̀tь | nìtь | jìlъ | tỳky | màti | kàmy | sě̀mę | čùdo | àgnę |

| Acc | xlě̀bъ | lě̀to | plàčь | rànǫ | bùřǫ | zę̀tь | nìtь | jìlъ | tỳkъvь | màterь | kàmenь | sě̀mę | čùdo | àgnę | |

| Gen | xlě̀ba | lě̀ta | plàča | ràny | bùřę̇ | zę̀tī | nìtī | jìlu | tỳkъve | màtere | kàmene | sě̀mene | čùdese | àgnęte | |

| Dat | xlě̀bu | lě̀tu | plàču | ràně | bùřī | zę̀ti | nìti | jìlovi | tỳkъvi | màteri | kàmeni | sě̀meni | čùdesi | àgnęti | |

| Inst | xlě̀bъmь | lě̀tъmь | plàčьmь | rànojǫ rànǭ[a] |

bùřējǫ bùřǭ[a] |

zę̀tьmь | nìtьjǫ nìťǭ[a] |

jìlъmъ | tỳkъvьjǫ tỳkъvljǭ[a] |

màterьjǫ màteřǭ[a] |

kàmenьmь | sě̀menьmь | čùdesьmь | àgnętьmь | |

| Loc | xlě̀bě | lě̀tě | plàči | ràně | bùřī | zę̀tī | nìtī | jìlū | tỳkъve | màtere | kàmene | sě̀mene | čùdese | àgnęte | |

| Plural | Nom | xlě̀bi | lě̀ta | plàči | ràny | bùřę̇ | zę̀tьjē zę̀ťē[a] |

nìti | jìlove | tỳkъvi | màteri | kàmene | sě̀menā | čùdesā | àgnętā |

| Acc | xlě̀by | lě̀ta | plàčę̇ | ràny | bùřę̇ | zę̀ti | nìti | jìly | tỳkъvi | màteri | kàmeni | sě̀menā | čùdesā | àgnętā | |

| Gen | xlě̀bъ | lě̀tъ | plàčь | rànъ | bùřь | zę̀tьjь zę̀tī[a] |

nìtьjь nìtī[a] |

jìlovъ | tỳkъvъ | màterъ | kàmenъ | sě̀menъ | čùdesъ | àgnętъ | |

| Dat | xlě̀bomъ | lě̀tomъ | plàčēmъ | rànamъ | bùřāmъ | zę̀tьmъ | nìtьmъ | jìlъmъ | tỳkъvьmъ | màterьmъ | kàmenьmъ | sě̀menьmъ | čùdesьmъ | àgnętьmъ | |

| Inst | xlě̀bȳ | lě̀tȳ | plàčī | rànamī | bùřāmī | zę̀tьmī | nìtьmī | jìlъmī | tỳkъvьmī | màterьmī | kàmenьmī | sě̀menȳ | čùdesȳ | àgnętȳ | |

| Loc | xlě̀bě̄xъ | lě̀tě̄xъ | plàčīxъ | rànaxъ | bùřāxъ | zę̀tьxъ | nìtьxъ | jìlъxъ | tỳkъvьxъ | màterьxъ | kàmenьxъ | sě̀menьxъ | čùdesьxъ | àgnętьxъ | |

- The first form is the result in languages without contraction over /j/ (e.g. Russian), while the second form is the result in languages with such contraction. This contraction can occur only when both vowels flanking /j/ are unstressed, but when it occurs, it occurs fairly early in Late Common Slavic, before Dybo's law (the accentual shift leading to AP b nouns). See below.

All single-syllable AP a stems are long. This is because all such stems had Balto-Slavic acute register in the root, which can only occur on long syllables. Single-syllable short and non-acute long syllables became AP b nouns in Common Slavic through the operation of Dybo's law. In stems of multiple syllables, there are also cases of short or neoacute accents in accent AP a, such as *osnòvā. These arose through advancement of the accent by Dybo's law onto a non-acute stem syllable (as opposed to onto an ending). When the accent was advanced onto a long non-acute syllable, it was retracted again by Ivšić's law to give a neoacute accent, in the same position as the inherited Balto-Slavic short or circumflex accent.

The distribution of short and long vowels in the stems without /j/ reflects the original vowel lengths, prior to the operation of van Wijk's law, Dybo's law and Stang's law, which led to AP b nouns and the differing lengths in /j/ stems.

AP b nouns

| Masc. long -o | Nt. long -o | Masc. short -jo | Nt. short -jo | Fem. short -ā | Masc. long -i | Fem. short -i | Masc. short -u | Fem. short -ū | Masc. short -n | Nt. short -n | Nt. long -nt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bull | wine | knife | bed | woman | way | door | ox | turtle | deer | tribe | baby animal | ||

| Singular | Nom | bỹkъ | vīnò | nõžь | ložè | ženà | pǫ̃tь | dvь̃rь | võlъ | želỳ | elỳ[a] | plemę̀ | zvě̄rę̀ |

| Acc | bỹkъ | vīnò | nõžь | ložè | ženǫ̀ | pǫ̃tь | dvь̃rь | võlъ | želъ̀vь | elènь | plemę̀ | zvě̄rę̀ | |

| Gen | bȳkà | vīnà | nožà | ložà | ženỳ | pǫ̃ti | dvь̃ri | volù | želъ̀ve | elène | plemène | zvě̄rę̀te | |

| Dat | bȳkù | vīnù | nožù | ložù | ženě̀ | pǭtì | dvьrì | volòvi | želъ̀vi | elèni | plemèni | zvě̄rę̀ti | |

| Inst | bȳkъ̀mь | vīnъ̀mь | nožь̀mь | ložь̀mь | ženòjǫ žẽnǫ[b] |

pǭtь̀mь | dvь̃rьjǫ dvь̃řǫ[b] |

volъ̀mь | želъ̀vьjǫ želъ̀vljǭ[b] |

elènьmь[c] | plemènьmь | zvě̄rę̀tьmь | |

| Loc | bȳcě̀ | vīně̀ | nožì | ložì | ženě̀ | pǫ̃ti | dvь̃ri | võlu | želъ̀ve | elène | plemène | zvě̄rę̀te | |

| Plural | Nom | bȳcì | vīnà | nožì | lõža | ženỳ | pǫ̃tьjē pǫ̃ťē[b] |

dvьrì | volòve | želъ̀vi | elène | plemènā | zvě̄rę̀tā |

| Acc | bȳkỳ | vīnà | nožę̇̀ | lõža | ženỳ | pǭtì | dvьrì | volỳ | želъ̀vi | elèni | plemènā | zvě̄rę̀tā | |

| Gen | bỹkъ | vĩnъ | nõžь | lõžь | žẽnъ | pǭtь̀jь pǫ̃ti[b] |

dvьrь̀jь dvь̃ri[b] |

volòvъ | želъ̀vъ | elènъ | plemènъ | zvě̄rę̀tъ | |

| Dat | bȳkòmъ | vīnòmъ | nõžemъ | lõžemъ | ženàmъ | pǭtь̀mъ | dvьrь̀mъ | volъ̀mъ | želъ̀vьmъ | elènьmъ | plemènьmъ | zvě̄rę̀tьmъ | |

| Inst | bỹky | vĩny | nõži | lõži | ženàmī | pǫ̃tьmī | dvь̃rьmī | võlъmī | želъ̀vьmī | elènьmī | plemènȳ | zvě̄rę̀tȳ | |

| Loc | bỹcěxъ | vĩněxъ | nõžixъ | lõžixъ | ženàxъ | pǭtь̀xъ | dvьrь̀xъ | volъ̀xъ | želъ̀vьxъ | elènьxъ | plemènьxъ | zvě̄rę̀tьxъ | |

- The first form is the result in languages without contraction over /j/ (e.g. Russian), while the second form is the result in languages with such contraction. This contraction can occur only when both vowels flanking /j/ are unstressed, but when it occurs, it occurs before Dybo's law. At that point in this paradigm, stress was initial, allowing contraction to occur, resulting in a long *ī. As a result, after Dybo's law moved stress onto the vowel, it was retracted again by Stang's law. Without contraction, only Dybo's law applied.

AP b jā-stem nouns are not listed here. The combination of Van Wijk's law and Stang's law would have originally produced a complex mobile paradigm in these nouns, different from the mobile paradigm of ā-stem and other nouns, but this was apparently simplified in Common Slavic times with a consistent neoacute accent on the stem, as if they were AP a nouns. The AP b jo-stem nouns were also simplified, but less dramatically, with consistent ending stress in the singular but consistent root stress in the plural, as shown. AP b s-stem noun are not listed here, because there may not have been any.

AP c nouns

| Masc. short -o | Nt. long -o | Masc. long -jo | Nt. short -jo | Fem. short -ā | Fem. long -jā | Masc. long -i | Fem. short -i | Masc. long -u | Fem. nonsyllabic -ū | Fem. short -r | Masc. short -n | Nt. short -n | Nt. short -s | Nt. long -nt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cart | belly | man | field | leg | soul | wild animal | bone | son | eyebrow | daughter | root | name | wheel | piglet | ||

| Singular | Nom | vȏzъ | břȗxo | mǫ̑žь | pȍľe | nogà | dušà | zvě̑rь | kȏstь | sy̑nъ | brỳ | dъ̏ťi | kȍry | jь̏mę | kȍlo | pȏrsę |

| Acc | vȏzъ | břȗxo | mǫ̑žь | pȍľe | nȍgǫ | dȗšǫ | zvě̑rь | kȏstь | sy̑nъ | brъ̑vь | dъ̏ťerь | kȍrenь[a] | jь̏mę | kȍlo | pȏrsę | |

| Gen | vȍza | břȗxa | mǫ̑ža | pȍľa | nogý | dušę̇́ | zvěrí | kostí | sy̑nu | brъ̏ve | dъ̏ťere | kȍrene | jь̏mene | kȍlese | pȏrsęte | |

| Dat | vȍzu | břȗxu | mǫ̑žu | pȍľu | nȍdźě | dȗšī | zvě̑ri | kȍsti | sy̑novi | brъ̏vi | dъ̏ťeri | kȍreni | jь̏meni | kȍlesi | pȏrsęti | |

| Inst | vȍzъmь | břȗxъmь | mǫ̑žьmь | pȍľьmь | nogojǫ́ | dušejǫ́ | zvě̑rьmь | kostьjǫ́ | sy̑nъmь | brъvьjǫ́ | dъťerьjǫ́ | kȍrenьmь[b] | jь̏menьmь | kȍlesьmь | pȏrsętьmь | |

| Loc | vȍzě | břȗśě | mǫ̑ži | pȍľi | nodźě̀ | dušì | zvěrí | kostí | synú | brъ̏ve | dъ̏ťere | kȍrene | jь̏mene | kȍlese | pȏrsęte | |

| Plural | Nom | vȍzi | břuxà | mǫ̑ži | poľà | nȍgy | dȗšę̇ | zvě̑rьjē zvě̑řē[c] |

kȍsti | sy̑nove | brъ̏vi | dъ̏ťeri | kȍrene | jьmenà | kolesà | porsętà |

| Acc | vȍzy | břuxà | mǫ̑žę̇ | poľà | nȍgy | dȗšę̇ | zvě̑ri | kȍsti | sy̑ny | brъ̏vi | dъ̏ťeri | kȍreni | jьmenà | kolesà | porsętà | |

| Gen | võzъ | břũxъ | mǫ̃žь | põľь | nõgъ | dũšь | zvěrь̃jь[d] | kostь̃jь[d] | synõvъ[e] | brъ̃vъ | dъťẽrъ | korẽnъ | jьmẽnъ | kolẽsъ | porsę̃tъ | |

| Dat | vozõmъ | břuxõmъ | mǫžẽmъ | poľẽmъ | nogàmъ | dušàmъ | zvě̑rьmъ[f] | kȍstьmъ[f] | sy̑nъmъ[f] | brъ̏vьmъ[f] | dъťẽrьmъ[g] | korẽnьmъ[g] | jьmẽnьmъ[g] | kolẽsьmъ[g] | porsę̃tьmъ[g] | |

| Inst | vozý | břuxý | mǫží | poľí | nogàmi | dušàmi | zvěrьmì | kostьmì | synъmì | brъvьmì | dъťerьmì | korenьmì | jьmený | kolesý | porsętý | |

| Loc | vozě̃xъ | břuśě̃xъ | mǫžĩxъ | poľĩxъ | nogàxъ | dušàxъ | zvě̑rьxъ[f] | kȍstьxъ[f] | sy̑nъxъ[f] | brъ̏vьxъ[f] | dъťẽrьxъ[g] | korẽnьxъ[g] | jьmẽnьxъ[g] | kolẽsьxъ[g] | porsę̃tьxъ[g] | |

- This word is reconstructed as *kȍręnь in Verweij, with a nasal vowel in the second syllable (and similarly for the rest of the paradigm). This is based on Czech dokořán. Verweij notes that *kȍrěnь is an alternative reconstruction, based on Serbo-Croatian kȍrijen. The form with medial -e-, however, comports with the majority of daughters and with other n-stem nouns.

- Verweij reconstructs i-stem genitive plural *zvěrь̃jь and *kostь̃jь, even though his reconstructed dative plural forms are *zvě̑rьmъ, *kȍstьmъ (see note below). This is because the strong yer preceding /j/ is a tense yer that is strong enough to block the supposed rule that skips intervening yers when retracting from a yer (see note below).

The accent pattern for the strong singular cases (nominative and accusative) and all plural cases is straightforward:

- All weak cases (genitive, dative, instrumental, locative) in the plural are ending-stressed.

- The *-à ending that marks the nominative singular of the (j)ā-stems and nominative–accusative plural of the neuter (j)o-stems is ending-stressed.

- All other strong cases (singular and plural) are stem-stressed.

For the weak singular cases, it can be observed:

- All such cases in the (j)o-stems are stem-stressed.

- All such cases in the j(ā)- and i-stems are end-stressed except the dative. (However, the masculine i-stem instrumental singular is stem-stressed because it is borrowed directly from the jo-stem.)

The long-rising versus short-rising accent on ending-accented forms with Middle Common Slavic long vowels reflects original circumflex versus acute register, respectively.

Adjectives

Adjective inflection had become more simplified compared to Proto-Indo-European. Only a single paradigm (in both hard and soft form) existed, descending from the PIE o- and a-stem inflection. I-stem and u-stem adjectives no longer existed. The present participle (from PIE *-nt-) still retained consonant stem endings.

Proto-Slavic had developed a distinction between "indefinite" and "definite" adjective inflection, much like Germanic strong and weak inflection. The definite inflection was used to refer to specific or known entities, similar to the use of the definite article "the" in English, while the indefinite inflection was unspecific or referred to unknown or arbitrary entities, like the English indefinite article "a". The indefinite inflection was identical to the inflection of o- and a-stem nouns, while the definite inflection was formed by suffixing the relative/anaphoric pronoun *jь to the end of the normal inflectional endings. Both the adjective and the suffixed pronoun were presumably declined as separate words originally, but already within Proto-Slavic they had become contracted and fused to some extent.

Verbs

The Proto-Slavic system of verbal inflection was somewhat simplified from the verbal system of Proto-Indo-European (PIE), although it was still rich in tenses, conjugations and verb-forming suffixes.

Grammatical categories

The PIE mediopassive voice disappeared entirely except for the isolated form vědě 'I know' in Old Church Slavonic (< Late PIE *woid-ai, a perfect mediopassive formation). However, a new analytic mediopassive was formed using the reflexive particle *sę, much as in the Romance languages. The imperative and subjunctive moods disappeared, and the old optative came to be used as the imperative instead.

In terms of PIE tense/aspect forms, the PIE imperfect was lost or merged with the PIE thematic aorist, and the PIE perfect was lost other than in the stem of the irregular verb *věděti 'to know' (from PIE *woyd-). The aorist was retained, preserving the PIE thematic and sigmatic aorist types (the former is generally termed the root aorist in Slavic studies), and a new productive aorist arose from the sigmatic aorist by various analogical changes; for example, replacing some of the original endings with thematic endings. (A similar development is observed in Greek and Sanskrit. In all three cases, the likely trigger was the phonological reduction of clusters like *-ss- and *-st- that arose when the original athematic endings were attached to the sigmatic *-s- affix.) A new synthetic imperfect was created by attaching a combination of the root and productive aorist endings to a stem suffix *-ěa- or *-aa-, of disputed origin. Various compound tenses were created; for example, to express the future, conditional, perfect, and pluperfect.

The three numbers (singular, dual, and plural) were all maintained, as were the different athematic and thematic endings. Only five athematic verbs exist: *věděti 'to know', *byti 'to be', *dati 'to give', *ěsti 'to eat', and *jьměti 'to have' (*dati has a finite stem *dad-, suggesting derivation by some sort of reduplication). A new set of "semi-thematic" endings were formed by analogy (corresponding to modern conjugation class II), combining the thematic first singular ending with otherwise athematic endings. Proto-Slavic also maintained a large number of non-finite formations, including the infinitive, the supine, a verbal noun, and five participles (present active, present passive, past active, past passive, and resultative). In large measure these directly continue PIE formations.

Aspect

Proto-Indo-European had an extensive system of aspectual distinctions ("present" vs. "aorist" vs. "perfect" in traditional terminology), found throughout the system. Proto-Slavic maintained part of this, distinguishing between aorist and imperfect in the past tense. In addition, Proto-Slavic evolved a means of forming lexical aspect (verbs inherently marked with a particular aspect) using various prefixes and suffixes, which was eventually extended into a systematic means of specifying grammatical aspect using pairs of related lexical verbs, each with the same meaning as the other but inherently marked as either imperfective (denoting an ongoing action) or perfective (denoting a completed action). The two sets of verbs interrelate in three primary ways:

- A suffix is added to a more basic perfective verb to form an imperfective verb.

- A prefix is added to a more basic imperfective verb (possibly the output of the previous step) to form a perfective verb. Often, multiple perfective verbs can be formed this way using different prefixes, one of which echoes the basic meaning of the source verb while the others add various shades of meaning (cf. English "write" vs. "write down" vs. "write up" vs. "write out").

- The two verbs are suppletive — either based on two entirely different roots, or derived from different PIE verb classes of the same root, often with root-vowel changes going back to PIE ablaut formations.

In Proto-Slavic and Old Church Slavonic, the old and new aspect systems coexisted, but the new aspect has gradually displaced the old one, and as a result most modern Slavic languages have lost the old imperfect, aorist, and most participles. A major exception, however, is Bulgarian (and also Macedonian to a fair extent), which has maintained both old and new systems and combined them to express fine shades of aspectual meaning. For example, in addition to imperfective imperfect forms and perfective aorist forms, Bulgarian can form a perfective imperfect (usually expressing a repeated series of completed actions considered subordinate to the "major" past actions) and an imperfective aorist (for "major" past events whose completion is not relevant to the narration).[10]

Proto-Slavic also had paired motion verbs (e.g. "run", "walk", "swim", "fly", but also "ride", "carry", "lead", "chase", etc.). One of the pair expresses determinate action (motion to a specified place, e.g. "I walked to my friend's house") and the other expressing indeterminate action (motion to and then back, and motion without a specified goal). These pairs are generally related using either the suffixing or suppletive strategies of forming aspectual verbs. Each of the pair is also in fact a pair of perfective vs. imperfective verbs, where the perfective variant often uses a prefix *po-.

Conjugation

Many different PIE verb classes were retained in Proto-Slavic, including (among others) simple thematic presents, presents in *-n- and *-y-, o-grade causatives in *-éye- and stative verbs in *-ē- (cf. similar verbs in the Latin -ēre conjugation) as well as factitive verbs in *-ā- (cf. the Latin -āre conjugation).

The forms of each verb were based on two basic stems, one for the present and one for the infinitive/past. The present stem was used before endings beginning in a vowel, the infinitive/past stem before endings beginning in a consonant. In Old Church Slavonic grammars, verbs are traditionally divided into four (or five) conjugation classes, depending on the present stem, known as Leskien's verb classes. However, this division ignores the formation of the infinitive stem. The following table shows the main classes of verbs in Proto-Slavic, along with their traditional OCS conjugation classes. The "present" column shows the ending of the third person singular present.

| Class | Present | Infinitive | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | -e-tь | -ti -ati |

*nestì, *nesȅtь "carry" *mę̀ti, *mьnetь "crumple" *gretì, *grebetь *peťì, *pečetь "bake" *žìti, *živetь "live" *bьrati, *beretь "take" *zъvati, *zovetь "call" |

PIE primary verbs, root ending in a consonant. Several irregular verbs, some showing ablaut. Not productive. Contains almost all infinitives in -Cti (e.g. *-sti or *-ťi), and a limited number of verbs in -ati. In verbs with an infinitive in -ti, various changes may occur with the last consonant. |

| (ę)-e-tь | -ti | *leťi, *lęžeti "lie down" *stati, *stanetь "stand (up)" |

PIE nasal-infix presents. The infinitive stem may end in either a vowel or a consonant. Not productive, only a few examples exist. | |

| 2nd | -ne-tь | -nǫ-ti | *rìnǫti, *rìnetь "push, shove" | From various PIE n-suffix verbs, the nasal vowel was a Slavic innovation. Two subclasses existed: those with -nǫ- also in the aorist and participle, and those without. |

| 3rd | -je-tь | -ti -ja-ti |

*bìti, *bь̏jetь "beat" *myti, *myjetь "wash" *duti, *dujetь "blow" *dajati, *dajetь "give" |

PIE primary verbs and presents in -ye-, root ending in a vowel. -j- is inserted into the hiatus between root and ending. Verbs with the plain -ti infinitive may have changes in the preceding vowel. Several irregular verbs, some showing ablaut. Not productive. |

| -je-tь | -a-ti | *sъlàti, *sъljȅtь "send" | PIE presents in -ye-, root ending in a consonant. The j caused iotation of the present stem. | |

| -aje-tь | -a-ti | *dělati, *dělajetь "do" | PIE denominatives in -eh₂-ye-. Remained very productive in Slavic. | |

| -ěje-tь | -ě-ti | *uměti, *umějetь "know, be able" | PIE stative verbs in -eh₁-ye-. Somewhat productive. | |

| -uje-tь | -ova-ti | *cělovàti, *cělùjetь "kiss" | An innovated Slavic denominative type. Very productive and usually remains so in all Slavic languages. | |

| 4th | -i-tь | -i-ti | *prosìti, *prõsitь "ask, make a request" | PIE causative-iteratives in -éye-, denominatives in -eyé-. Remained very productive. |

| -i-tь -i-tь |

-ě-ti -a-ti |

*mьněti, *mьnitь "think" *slỳšati, *slỳšitь "hear" |

A relatively small class of stative verbs. The infinitive in -ati was a result of iotation, which triggered the change *jě > *ja. In the present tense, the first-person singular shows consonant alternation (caused by *j): *xoditi "to walk" : *xoďǫ, *letěti "to fly" : *leťǫ, *sъpati "to sleep" : *sъpľǫ (with epenthetic *l). The stem of the infinitives in *-ati (except for *sъpati) ends in *j or the so-called "hushing sound". | |

| 5th | -(s)-tь | -ti | *bỳti, *ȅstь "be" *dàti, *dãstь "give" *ě̀sti, *ě̃stь "eat" *jьměti, *jьmatь "have" *věděti, *věstь "know" |

PIE athematic verbs. Only five verbs, all irregular in one way or another, including their prefixed derivations. |

Accent

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2013) |

The same three classes occurred in verbs as well. However, different parts of a verb's conjugation could have different accent classes, due to differences in syllable structure and sometimes also due to historical anomalies. Generally, when verbs as a whole are classified according to accent paradigm, the present tense paradigm is taken as the base.

AP a verbs

Wiktionary has a category on Proto-Slavic verbs with accent paradigm a.

Verbs in accent paradigm a are the most straightforward, with acute accent on the stem throughout the paradigm.

AP b verbs

Wiktionary has a category on Proto-Slavic verbs with accent paradigm b.

Verbs with a present stem in *-e- have short *-è- in the present tense and acute *-ě̀- or *-ì- in the imperative. Verbs with a present stem in *-i- have acute *-ì- in the imperative, but a historical long circumflex in the present tense, and therefore retract it into a neoacute on the stem in all forms with a multisyllabic ending. The infinitive is normally accented on the first syllable of the ending, which may be a suffixal vowel (*-àti, *-ìti) or the infinitive ending itself (*-tì).

In a subset of verbs with the basic *-ti ending, known as AP a/b verbs, the infinitive has a stem acute accent instead, *mèlti, present *meľètь. Such verbs historically had acute stems ending in a long vowel or diphthong, and should have belonged to AP a. However, the stem was followed by a consonant in some forms (e.g. the infinitive) and by a vowel in others (the present tense). The forms with a following vowel were resyllabified into a short vowel + sonorant, which also caused the loss of the acute in these forms, because the short vowel could not be acuted. The short vowel in turn was subject to Dybo's law, while the original long vowel/diphthong remained acuted and thus resisted the change.

AP c verbs

Wiktionary has a category on Proto-Slavic verbs with accent paradigm c.

Verbs in accent paradigm c have the accent on the final syllable in the present tense, except in the first-person singular, which has a short or long falling accent on the stem. Where the final syllable contains a yer, the accent is retracted onto the thematic vowel and becomes neoacute (short on *e, long on *i). In the imperative, the accent is on the syllable after the stem, with acute *-ě̀- or *-ì-.

In verbs with a vowel suffix between stem and ending, the accent in the infinitive falls on the vowel suffix (*-àti, *-ě̀ti, *-ìti). In verbs with the basic ending *-ti, the accentuation is unpredictable. Most verbs have the accent on the *-tì, but if the infinitive was historically affected by Hirt's law, the accent is acute on the stem instead. Meillet's law did not apply in these cases.

Example of evolution from PIE to PS

Summarize

Perspective

PIE: Proto-Indo-European

PBS: Proto-Balto-Slavic

PS: Proto-Slavic

| Case | Singular

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

Dual

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

Plural

(PS < PBS < PIW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | *vь̑lkъ < *wilkás < *wĺ̥kʷos | *vь̑lka < *wílkōˀ < *wĺ̥kʷoh₁ | *vь̑lci < *wilkái(ˀ) < *wĺ̥kʷoes |

| Gen. | *vь̑lka < *wílkā < *wĺ̥kʷosyo | *vьlkù < *wilkā́u(ˀ) < ? | *vь̃lkъ < *wilkṓn <*wĺ̥kʷoHom |

| Dat. | *vь̑lku < *wílkōi < *wĺ̥kʷoey | *vьlkomà < *wilkámā(ˀ) < ? | *vьlkòmъ < *wilkámas < *wĺ̥kʷomos |

| Acc. | *vь̑lkъ < *wílkan < *wĺ̥kʷom | *vь̑lka < *wílkōˀ < *wĺ̥kʷoh₁ | *vь̑lky < *wílkō(ˀ)ns < *wĺ̥kʷoms |

| Voc. | *vь̑lce < *wílke < *wĺ̥kʷe | *vь̑lka < *wílkōˀ < *wĺ̥kʷoh₁ | *vь̑lci < *wilkái(ˀ) < *wĺ̥kʷoes |

| Loc. | *vь̑lcě < *wílkai < *wĺ̥kʷoy | *vьlkù < *wilkā́u(ˀ) < ? | *vьlcě̃xъ < *wilkáišu < *wĺ̥kʷoysu |

| Instr. | *vь̑lkъmь, *vь̑lkomь < *wílkōˀ < *wĺ̥kʷoh₁ | *vьlkomà < *wilkámāˀ < ? | *vьlký < *wilkṓis < *wĺ̥kʷōys |

| Case | Singular

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

Dual

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

Plural

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | *bordà < *bardā́ˀ < *bʰardʰéh₂ | *bȏrdě < *bárdāiˀ < *bʰardʰéh₂h₁(e) | *bȏrdy < *bárdās < *bʰardʰéh₂es |

| Gen. | *bordý < *bardā́(ˀ)s < *bʰardʰéh₂s | *bordù < *bardā́u(ˀ) < ? | *bõrdъ < *bardṓn < *bʰardʰéh₂oHom |

| Dat. | *bordě̀ < *bárdāi < *bʰardʰéh₂ey | *bordàma < *bardā́(ˀ)mā(ˀ) < ? | *bordàmъ < *bardā́(ˀ)mas < *bʰardʰéh₂mos |

| Acc. | *bȏrdǫ < *bárdā(ˀ)n < *bʰardʰā́m | *bȏrdě < *bárdāiˀ < *bʰardʰéh₂h₁(e) | *bȏrdy < *bárdā(ˀ)ns < *bʰardʰéh₂m̥s |

| Voc. | *bordo < *bárda < *bʰardʰéh₂ | *bȏrdě < *bárdāiˀ < *bʰardʰéh₂h₁(e) | *bȏrdy < *bárdās < *bʰardʰéh₂es |

| Loc. | *bȏrdě < *bardā́iˀ < *bʰardʰéh₂i | *bordù < *bardā́u(ˀ) < ? | *bordàsъ, *bordàxъ < *bardā́(ˀ)su < *bʰardʰéh₂su |

| Instr. | *bordojǫ́ < *bárdāˀn < *bʰardʰéh₂h₁ | *bordàma < *bardā́(ˀ)māˀ < ? | *bordàmi < *bardā́(ˀ)mīˀs < *bʰardʰéh₂mis |

| Case | Singular

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

Dual

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

Plural

(PS < PBS < PIE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | *jь̏go < *jūˀga < *yugóm | *jь̏dzě < *jūˀgai < *yugóy(h₁) | *jьgà < *jūˀgāˀ < *yugéh₂ |

| Gen. | *jь̏ga < *jūˀgā < *yugósyo | *jьgù < *jūˀgāu(ˀ) < ? | *jь̀gъ < *jūˀgōn < *yugóHom |

| Dat. | *jь̏gu < *jūˀgōi < *yugóey | *jьgomà < *jūˀgamā(ˀ) < ? | *jьgòmъ < *jūˀgamas < *yugómos |

| Acc. | *jь̏go < *jūˀga < *yugóm | *jь̏dzě < *jūˀgai < *yugóy(h₁) | *jьgà < *jūˀgāˀ < *yugéh₂ |

| Voc. | *jь̏go < *jūˀgōˀ < *yugóh₁ | *jь̏dzě < *jūˀgai < *yugóy(h₁) | *jьgà < *jūˀgāˀ < *yugéh₂ |

| Loc. | *jь̏dzě < *jūˀgai < *yugóy | *jьgù < *jūˀgāu(ˀ) < ? | *jьdzě̃xъ < *jūˀgaišu < *yugóysu |

| Instr. | *jь̏gъmь, *jь̏gomь < *jūˀgōˀ < *yugóm | *jьgomà < *jūˀgamāˀ < ? | *jьgý < *jūˀgōis < *yugṓys |

Sample text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in reconstructed Proto-Slavic language, written in Latin alphabet:

- Vьśi ľudьje rodętь sę svobodьni i orvьni vъ dostojьnьstvě i pravěxъ. Oni sǫtь odařeni orzumomь i sъvěstьjǫ i dъlžьni vesti sę drugъ kъ drugu vъ duśě bratrьstva.[citation needed]

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:[11]

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.