Same-sex marriage

Marriage of persons of the same sex or gender From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same legal sex. As of 2025,[update] marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 38 countries, with a total population of 1.5 billion people (20% of the world's population). The most recent jurisdiction to legalize same-sex marriage is Thailand.

Same-sex marriage is legally recognized in a large majority of the world's developed countries; notable exceptions are Italy, Japan, South Korea and the Czech Republic. Adoption rights are not necessarily covered, though most states with same-sex marriage allow those couples to jointly adopt as other married couples can. Some countries, such as Nigeria and Russia, restrict advocacy for same-sex marriage.[1] A few of these are among the 35 countries (as of 2023) that constitutionally define marriage to prevent marriage between couples of the same sex, with most of those provisions enacted in recent decades as a preventative measure. Other countries have constitutionally mandated Islamic law, which is generally interpreted as prohibiting marriage between same-sex couples.[citation needed] In six of the former and most of the latter, homosexuality itself is criminalized.

There are records of marriage between men dating back to the first century.[2] Michael McConnell and Jack Baker[3][4] are the first same sex couple in modern recorded history[5] known to obtain a marriage license,[6] have their marriage solemnized, which occurred on September 3, 1971, in Minnesota,[7] and have it legally recognized by any form of government.[8][9] The first law providing for marriage equality between same-sex and opposite-sex couples was passed in the continental Netherlands in 2000 and took effect on 1 April 2001.[10] The application of marriage law equally to same-sex and opposite-sex couples has varied by jurisdiction, and has come about through legislative change to marriage law, court rulings based on constitutional guarantees of equality, recognition that marriage of same-sex couples is allowed by existing marriage law, and by direct popular vote, such as through referendums and initiatives.[11][12] The most prominent supporters of same-sex marriage are the world's major medical and scientific communities,[13][14][15] human rights and civil rights organizations, and some progressive religious groups,[16][17][18] while its most prominent opponents are from conservative religious groups (some of which nonetheless support same-sex civil unions providing legal protections for same-sex couples).[19][20] Polls consistently show continually rising support for the recognition of same-sex marriage in all developed democracies and in many developing countries.

Scientific studies show that the financial, psychological, and physical well-being of gay people is enhanced by marriage, and that the children of same-sex parents benefit from being raised by married same-sex couples within a marital union that is recognized by law and supported by societal institutions. At the same time, no harm is done to the institution of marriage among heterosexuals.[21] Social science research indicates that the exclusion of same-sex couples from marriage stigmatizes and invites public discrimination against gay and lesbian people, with research repudiating the notion that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon restricting marriage to heterosexuals.[22][23][24] Same-sex marriage can provide those in committed same-sex relationships with relevant government services and make financial demands on them comparable to that required of those in opposite-sex marriages, and also gives them legal protections such as inheritance and hospital visitation rights.[25] Opposition is often based on religious teachings, such as the view that marriage is meant to be between men and women, and that procreation is the natural goal of marriage.[26][20] Other forms of opposition are based on claims such as that homosexuality is unnatural and abnormal, that the recognition of same-sex unions will promote homosexuality in society, and that children are better off when raised by opposite-sex couples. These claims are refuted by scientific studies, which show that homosexuality is a natural and normal variation in human sexuality, that sexual orientation is not a choice, and that children of same-sex couples fare just as well as the children of opposite-sex couples.[13]

Terminology

Summarize

Perspective

Alternative terms

Some proponents of the legal recognition of same-sex marriage—such as Marriage Equality USA (founded in 1998), Freedom to Marry (founded in 2003), Canadians for Equal Marriage, and Marriage for All Japan - used the terms marriage equality and equal marriage to signal that their goal was for same-sex marriage to be recognized on equal ground with opposite-sex marriage.[27][28][29][30][31][32] The Associated Press recommends the use of same-sex marriage over gay marriage.[33] In deciding whether to use the term gay marriage, it may also be noted that not everyone in a same-sex marriage is gay – for example, some are bisexual – and therefore using the term gay marriage is sometimes considered erasure of such people.[34][35]

Use of the term marriage

Anthropologists have struggled to determine a definition of marriage that absorbs commonalities of the social construct across cultures around the world.[36][37] Many proposed definitions have been criticized for failing to recognize the existence of same-sex marriage in some cultures, including those of more than 30 African peoples, such as the Kikuyu and Nuer.[37][38][39]

With several countries revising their marriage laws to recognize same-sex couples in the 21st century, all major English dictionaries have revised their definition of the word marriage to either drop gender specifications or supplement them with secondary definitions to include gender-neutral language or explicit recognition of same-sex unions.[40][41] The Oxford English Dictionary has recognized same-sex marriage since 2000.[42]

Opponents of same-sex marriage who want marriage to be restricted to pairings of a man and a woman, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Catholic Church, and the Southern Baptist Convention, use the term traditional marriage to mean opposite-sex marriage.[20]

History

Summarize

Perspective

Ancient

A reference to marriage between same-sex couples appears in the Sifra, which was written in the 3rd century CE. The Book of Leviticus prohibited homosexual relations, and the Hebrews were warned not to "follow the acts of the land of Egypt or the acts of the land of Canaan" (Lev. 18:22, 20:13). The Sifra clarifies what these ambiguous "acts" were, and that they included marriage between same-sex couples: "A man would marry a man and a woman a woman, a man would marry a woman and her daughter, and a woman would be married to two men."[43]

A few scholars believe that in the early Roman Empire some male couples were celebrating traditional marriage rites in the presence of friends. Male–male weddings are reported by sources that mock them; the feelings of the participants are not recorded.[44] Various ancient sources state that the emperor Nero celebrated two public weddings with males, once taking the role of the bride (with a freedman Pythagoras), and once the groom (with Sporus); there may have been a third in which he was the bride.[45] In the early 3rd century AD, the emperor Elagabalus is reported to have been the bride in a wedding to his male partner. Other mature men at his court had husbands, or said they had husbands in imitation of the emperor.[46] Roman law did not recognize marriage between males, but one of the grounds for disapproval expressed in Juvenal's satire is that celebrating the rites would lead to expectations for such marriages to be registered officially.[47] As the empire was becoming Christianized in the 4th century, legal prohibitions against marriage between males began to appear.[47]

Contemporary

Michael McConnell and Jack Baker[3][4] are the first same sex couple in modern recorded history[5] known to obtain a marriage license,[6] have their marriage solemnized, which occurred on September 3, 1971, in Minnesota,[7] and have it legally recognized by any form of government.[8][9] Historians variously trace the beginning of the modern movement in support of same-sex marriage to anywhere from around the 1980s to the 1990s. During the 1980s in the United States, the AIDS epidemic led to increased attention on the legal aspects of same-sex relationships.[48] Andrew Sullivan made the first case for same sex marriage in a major American journal in 1989,[49] published in The New Republic.[50]

In 1989, Denmark became the first country to legally recognize a relationship for same-sex couples, establishing registered partnerships, which gave those in same-sex relationships "most rights of married heterosexuals, but not the right to adopt or obtain joint custody of a child".[51] In 2001, the continental Netherlands became the first country to broaden marriage laws to include same-sex couples.[10][52] Since then, same-sex marriage has been established by law in 38 other countries, including most of the Americas and Western Europe. Yet its spread has been uneven — South Africa is the only country in Africa to take the step; Taiwan and Thailand are the only ones in Asia.[53][54]

Timeline

Summarize

Perspective

The summary table below lists in chronological order the sovereign states (the United Nations member states and Taiwan) that have legalized same-sex marriage. As of 2025, 38 states have legalized in some capacity.[55]

Dates are when marriages between same-sex couples began to be officially certified, or when local laws were passed if marriages were already legal under higher authority.

Same-sex marriage around the world

Summarize

Perspective

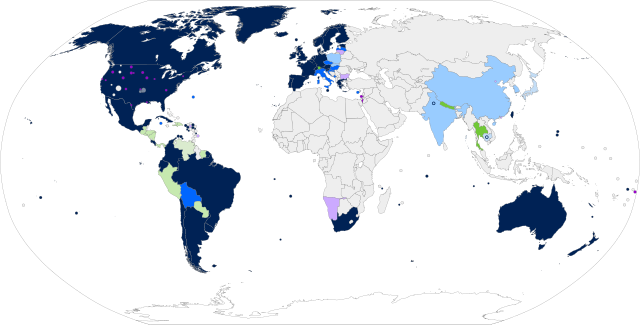

Same-sex marriage is legally performed and recognized in 38 countries: Andorra, Argentina, Australia,[a] Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark,[b] Ecuador,[c] Estonia, Finland, France,[d] Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico,[e] the Netherlands,[f] New Zealand,[g] Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, the United Kingdom,[h] the United States,[i] and Uruguay.[56] Same-sex marriage performed remotely or abroad is recognized with full marital rights by Israel.[57]

Marriage open to same-sex couples

Same-sex marriage recognized with full rights when performed remotely or abroad

Civil unions or domestic partnerships

Unregistered cohabitation or legal guardianship

Nonbinding certification

Limited recognition of marriage performed in certain other jurisdictions (residency rights for spouses)

No legal recognition of same-sex unions

Same-sex marriage is under consideration by the legislature or the courts in El Salvador,[58][59] Italy,[60][61] Japan,[62] Nepal,[j] and Venezuela.[68]

Civil unions are being considered in a number of countries, including Kosovo,[69] Peru,[70] the Philippines[71] and Poland.[72]

On 12 March 2015, the European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution encouraging EU institutions and member states to "[reflect] on the recognition of same-sex marriage or same-sex civil union as a political, social and human and civil rights issue".[73][74]

In response to the international spread of same-sex marriage, a number of countries have enacted preventative constitutional bans, with the most recent being Mali in 2023, and Gabon in 2024. In other countries, such restrictions and limitations are effected through legislation. Even before same-sex marriage was first legislated, some countries had constitutions that specified that marriage was between a man and a woman.

Same-sex marriage banned by constitutionally mandated religious law

No constitutional ban

International court rulings

European Court of Human Rights

In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled in Schalk and Kopf v Austria, a case involving an Austrian same-sex couple who were denied the right to marry.[75] The court found, by a vote of 4 to 3, that their human rights had not been violated.[76] The court further stated that same-sex unions are not protected under art. 12 of ECHR ("Right to marry"), which exclusively protects the right to marry of opposite-sex couples (without regard if the sex of the partners is the result of birth or of sex change), but they are protected under art. 8 of ECHR ("Right to respect for private and family life") and art. 14 ("Prohibition of discrimination").[77]

Article 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights states that: "Men and women of marriageable age have the right to marry and to found a family, according to the national laws governing the exercise of this right",[78] not limiting marriage to those in a heterosexual relationship. However, the ECHR stated in Schalk and Kopf v Austria that this provision was intended to limit marriage to heterosexual relationships, as it used the term "men and women" instead of "everyone".[75] Nevertheless, the court accepted and is considering cases concerning same-sex marriage recognition, e.g. Andersen v Poland.[79] In 2021, the court ruled in Fedotova and Others v. Russia—followed by later judgements concerning other member states—that countries must provide some sort of legal recognition to same-sex couples, although not necessarily marriage.[80]

European Union

On 5 June 2018, the European Court of Justice ruled, in a case from Romania, that, under the specific conditions of the couple in question, married same-sex couples have the same residency rights as other married couples in an EU country, even if that country does not permit or recognize same-sex marriage.[81][82] However, the ruling was not implemented in Romania and on 14 September 2021 the European Parliament passed a resolution calling on the European Commission to ensure that the ruling is respected across the EU.[83][84]

Inter-American Court of Human Rights

On 8 January 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) issued an advisory opinion that states party to the American Convention on Human Rights should grant same-sex couples accession to all existing domestic legal systems of family registration, including marriage, along with all rights that derive from marriage. The Court recommended that governments issue temporary decrees recognizing same-sex marriage until new legislation is brought in. They also said that it was inadmissible and discriminatory for a separate legal provision to be established (such as civil unions) instead of same-sex marriage.[85]

Other arrangements

Summarize

Perspective

Civil unions

Civil union, civil partnership, domestic partnership, registered partnership, unregistered partnership, and unregistered cohabitation statuses offer varying legal benefits of marriage. As of 23 April 2025, countries that have an alternative form of legal recognition other than marriage on a national level are: Bolivia, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Monaco, Montenegro and San Marino.[87][88] Same-sex marriage performed remotely or abroad is recognized with full marital rights by Israel. Poland offers more limited rights. Additionally, various cities and counties in Cambodia and Japan offer same-sex couples varying levels of benefits, which include hospital visitation rights and others.

Additionally, eighteen countries that have legally recognized same-sex marriage also have an alternative form of recognition for same-sex couples, usually available to heterosexual couples as well: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, the United Kingdom and Uruguay.[89][90][91][92]

They are also available in parts of the United States (Arizona,[k] California, Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, Nevada and Oregon) and Canada.[93][94]

Non-sexual same-sex marriage

Kenya

Female same-sex marriage is practiced among the Gikuyu, Nandi, Kamba, Kipsigis, and to a lesser extent neighboring peoples. About 5–10% of women are in such marriages. However, this is not seen as homosexual, but is instead a way for families without sons to keep their inheritance within the family.[95]

Nigeria

Among the Igbo people and probably other peoples in the south of the country, there are circumstances where a marriage between women is considered appropriate, such as when a woman has no child and her husband dies, and she takes a wife to perpetuate her inheritance and family lineage.[96]

Studies

Summarize

Perspective

The American Anthropological Association stated on 26 February 2004:

The results of more than a century of anthropological research on households, kinship relationships, and families, across cultures and through time, provide no support whatsoever for the view that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution. Rather, anthropological research supports the conclusion that a vast array of family types, including families built upon same-sex partnerships, can contribute to stable and humane societies.[24]

Research findings from 1998 to 2015 from the University of Virginia, Michigan State University, Florida State University, the University of Amsterdam, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Stanford University, the University of California-San Francisco, the University of California-Los Angeles, Tufts University, Boston Medical Center, the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, and independent researchers also support the findings of this study.[97][vague]

The overall socio-economic and health effects of legal access to same-sex marriage around the world have been summarized by Badgett and co-authors.[98] The review found that sexual minority individuals took-up legal marriage when it became available to them (but at lower rates than different-sex couples). There is instead no evidence that same-sex marriage legalization affected different-sex marriages. On the health side, same-sex marriage legalization increased health insurance coverage for individuals in same-sex couples (in the US), and it led to improvements in sexual health among men who have sex with men, while there is mixed evidence on mental health effects among sexual minorities. In addition, the study found mixed evidence on a range of downstream social outcomes such as attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people and employment choices of sexual minorities.

Health

As of 2006[update], the data of current psychological and other social science studies on same-sex marriage in comparison to mixed-sex marriage indicate that same-sex and mixed-sex relationships do not differ in their essential psychosocial dimensions; that a parent's sexual orientation is unrelated to their ability to provide a healthy and nurturing family environment; and that marriage bestows substantial psychological, social, and health benefits. Same-sex parents and carers and their children are likely to benefit in numerous ways from legal recognition of their families, and providing such recognition through marriage will bestow greater benefit than civil unions or domestic partnerships.[99][100][needs update] Studies in the United States have correlated legalization of same-sex marriage to lower rates of HIV infection,[101][102] psychiatric disorders,[103][104] and suicide rate in the LGBT population.[105][106]

Issues

Summarize

Perspective

While few societies have recognized same-sex unions as marriages,[needs update] the historical and anthropological record reveals a large range of attitudes towards same-sex unions ranging from praise, through full acceptance and integration, sympathetic toleration, indifference, prohibition and discrimination, to persecution and physical annihilation.[citation needed] Opponents of same-sex marriages have argued that same-sex marriage, while doing good for the couples that participate in them and the children they are raising,[107] undermines a right of children to be raised by their biological mother and father.[108] Some supporters of same-sex marriages take the view that the government should have no role in regulating personal relationships,[109] while others argue that same-sex marriages would provide social benefits to same-sex couples.[l] The debate regarding same-sex marriages includes debate based upon social viewpoints as well as debate based on majority rules, religious convictions, economic arguments, health-related concerns, and a variety of other issues.[citation needed]

Parenting

Scientific literature indicates that parents' financial, psychological and physical well-being is enhanced by marriage and that children benefit from being raised by two parents within a legally recognized union (either a mixed-sex or same-sex union). As a result, professional scientific associations have argued for same-sex marriage to be legally recognized as it will be beneficial to the children of same-sex parents or carers.[14][15][110][111][112]

Scientific research has been generally consistent in showing that lesbian and gay parents are as fit and capable as heterosexual parents, and their children are as psychologically healthy and well-adjusted as children reared by heterosexual parents.[15][112][113][114] According to scientific literature reviews, there is no evidence to the contrary.[99][115][116][117][needs update]

Compared to heterosexual couples, same-sex couples have a greater need for adoption or assisted reproductive technology to become parents. Lesbian couples often use artificial insemination to achieve pregnancy, and reciprocal in vitro fertilization (where one woman provides the egg and the other gestates the child) is becoming more popular in the 2020s, although many couples cannot afford it. Surrogacy is an option for wealthier gay male couples, but the cost is prohibitive. Other same-sex couples adopt children or raise the children from earlier opposite-sex relationships.[118][119]

Adoption

Joint adoption allowed

Second-parent (stepchild) adoption allowed

No laws allowing adoption by same-sex couples and no same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage but adoption by married same-sex couples not allowed

All states that allow same-sex marriage also allow the joint adoption of children by those couples with the exception of Ecuador and a third of states in Mexico, though such restrictions have been ruled unconstitutional in Mexico. In addition, Bolivia, Croatia and Israel, which do not recognize same-sex marriage, nonetheless permit joint adoption by same-sex couples. Some additional states do not recognize same-sex marriage but allow stepchild adoption by couples in civil unions, namely the Czech Republic and San Marino.[citation needed]

Transgender and intersex people

This article or section possibly contains original synthesis. Source material should verifiably mention and relate to the main topic. (May 2017) |

The legal status of same-sex marriage may have implications for the marriages of couples in which one or both parties are transgender, depending on how sex is defined within a jurisdiction. Transgender and intersex individuals may be prohibited from marrying partners of the "opposite" sex or permitted to marry partners of the "same" sex due to legal distinctions.[citation needed] In any legal jurisdiction where marriages are defined without distinction of a requirement of a male and female, these complications do not occur. In addition, some legal jurisdictions recognize a legal and official change of gender, which would allow a transgender male or female to be legally married in accordance with an adopted gender identity.[120]

In the United Kingdom, the Gender Recognition Act 2004 allows a person who has lived in their chosen gender for at least two years to receive a gender recognition certificate officially recognizing their new gender. Because in the United Kingdom marriages were until recently only for mixed-sex couples and civil partnerships are only for same-sex couples, a person had to dissolve their civil partnership before obtaining a gender recognition certificate[citation needed], and the same was formerly true for marriages in England and Wales, and still is in other territories. Such people are then free to enter or re-enter civil partnerships or marriages in accordance with their newly recognized gender identity. In Austria, a similar provision requiring transsexual people to divorce before having their legal sex marker corrected was found to be unconstitutional in 2006.[121] In Quebec, prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage, only unmarried people could apply for legal change of gender. With the advent of same-sex marriage, this restriction was dropped. A similar provision including sterilization also existed in Sweden, but was phased out in 2013.[122] In the United States, transgender and intersex marriages was subject to legal complications.[123] As definitions and enforcement of marriage are defined by the states, these complications vary from state to state,[124] as some of them prohibit legal changes of gender.[125]

Divorce

In the United States before the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, couples in same-sex marriages could only obtain a divorce in jurisdictions that recognized same-sex marriages, with some exceptions.[126]

Judicial and legislative

There are differing positions regarding the manner in which same-sex marriage has been introduced into democratic jurisdictions. A "majority rules" position holds that same-sex marriage is valid, or void and illegal, based upon whether it has been accepted by a simple majority of voters or of their elected representatives.[127]

In contrast, a civil rights view holds that the institution can be validly created through the ruling of an impartial judiciary carefully examining the questioning and finding that the right to marry regardless of the gender of the participants is guaranteed under the civil rights laws of the jurisdiction.[16]

Public opinion

Summarize

Perspective

|

5⁄6+

2⁄3+ |

1⁄2+

1⁄3+ |

1⁄6+

<1⁄6 |

no polls

|

Numerous polls and studies on the issue have been conducted. A trend of increasing support for same-sex marriage has been revealed across many countries of the world, often driven in large part by a generational difference in support. Polling that was conducted in developed democracies in this century shows a majority of people in support of same-sex marriage. Support for same-sex marriage has increased across every age group, political ideology, religion, gender, race and region of various developed countries in the world.[129][130][131][132][133][needs update]

Various detailed polls and studies on same-sex marriage that were conducted in several countries show that support for same-sex marriage significantly increases with higher levels of education and is also significantly stronger among younger generations, with a clear trend of continually increasing support.[134]

- Greater support with youth

Pew Research polling results from 32 countries found 21 with statistically higher support for same-sex marriage among those under 35 than among those over 35 in 2022–2023. Countries with the greatest absolute difference are placed to the left in the following chart. Countries without a significant generational difference are placed to the right.[134]

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Taiw

Mex

Sing

ROK

HK

Gre

Pol

Viet

Thai

Jpn

Cam

Braz

USA

Arg

Ital

Oz

S. Af.

Sri Lanka

Keny

Swed

Malay

Neth

Spa

Fran

Germ

Cana

UK

India

Isra

Hung

Indo

Nigeria

- over 35

- additional support from those under 35

A 2016 survey by the Varkey Foundation found similarly high support of same-sex marriage (63%) among 18–21-year-olds in an online survey of 18 countries around the world.[135][136][137]

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Germ

Cana

Oz

UK

NZ

Fran

Ital

Arg

USA

Braz

Chin

S. Af.

India

Jpn

Isra

ROK

Turk

Nigeria

(The sampling error is approx. 4% for Nigeria and 3% for the other countries. Because of legal constraints, the question on same-sex marriage was not asked in the survey countries of Russia and Indonesia.)

- Opinion polls for same-sex marriage by country

Same-sex marriage performed nationwide

Same-sex marriage performed in some parts of the country

Civil unions or registered partnerships nationwide

Civil unions or registered partnerships pending

Same-sex marriage rights pending

Same-sex sexual activity is illegal

| Country | Pollster | Year | For[m] | Against[m] | Neither[n] | Margin of error |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% |

73% (74%) |

1% | [138] | ||

| Institut d'Estudis Andorrans | 2013 | 70% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

11% | [139] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | – | – | [140] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (81%) |

16% [9% support some rights] (19%) |

15% not sure | ±5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 67% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

7% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 3% (3%) |

96% (97%) |

1% | ±3% | [143] [144] | |

| 2021 | 46% |

[145] | |||||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 64% (73%) |

25% [13% support some rights] (28%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 75% (77%) |

23% | 2% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [146] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2015 | 11% | – | – | [147] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 16% (16%) |

81% (84%) |

3% | ±4% | [143] [144] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (78%) |

19% [9% support some rights] (22%) |

12% not sure | ±5% | [141] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% | 19% | 2% not sure | [146] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 8% | – | – | [147] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 35% | 65% | – | ±1.0% | [140] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% (27%) |

71% (73%) |

3% | [138] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

31% [17% support some rights] (38%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [o] | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 52% (57%) |

40% (43%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [146] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 57% (58%) |

42% | 1% | [142] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 65% (75%) |

22% [10% support some rights] (25%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 79% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

6% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Cadem | 2024 | 77% (82%) |

22% (18%) |

2% | ±3.6% | [148] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 43% (52%) |

39% [20% support some rights] (48%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [o] | [149] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 46% (58%) |

33% [19% support some rights] (42%) |

21% | ±5% [o] | [141] | |

| CIEP | 2018 | 35% | 64% | 1% | [150] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

7% | [146] | ||

| Apretaste | 2019 | 63% | 37% | – | [151] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% (53%) |

44% (47%) |

6% | [146] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 60% | 34% | 6% | [146] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 93% | 5% | 2% | [146] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 10% | 90% | – | ±1.1% | [140] | |

| CDN 37 | 2018 | 45% | 55% | - | [152] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2019 | 23% (31%) |

51% (69%) |

26% | [153] | ||

| Universidad Francisco Gavidia | 2021 | 82.5% | – | [154] | |||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 41% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

8% | [146] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 76% (81%) |

18% (19%) |

6% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 62% (70%) |

26% [16% support some rights] (30%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 82% (85%) |

14% (15%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% (85%) |

14 (%) (15%) |

7% | [146] | ||

| Women's Initiatives Supporting Group | 2021 | 10% (12%) |

75% (88%) |

15% | [155] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (83%) |

18% [10% support some rights] (20%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 80% (82%) |

18% | 2% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% (87%) |

13%< | 3% | [146] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 48% (49%) |

49% (51%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 57% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

3% | [146] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | 88% | – | ±1.4%c | [140] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 23% | 77% | – | ±1.1% | [140] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 21% | 79% | – | ±1.3% | [147] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 5% | 95% | – | ±0.3% | [140] | |

| CID Gallup | 2018 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [156] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 58% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

2% | [142] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 44% (56%) |

35% [18% support some rights] (44%) |

21% not sure | ±5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 31% (33%) |

64% (67%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

52% (55%) |

6% | [146] | ||

| Gallup | 2006 | 89% | 11% | – | [157] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 53% (55%) |

43% (45%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 5% | 92% (95%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 68% (76%) |

21% [8% support some rights] (23%) |

10% | ±5%[o] | [141] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 86% (91%) |

9% | 5% | [146] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 36% (39%) |

56% (61%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 58% (66%) |

29% [19% support some rights] (33%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 73% (75%) |

25% | 2% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 69% (72%) |

27% (28%) |

4% | [146] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 16% | 84% | – | ±1.0% | [140] | |

| Kyodo News | 2023 | 64% (72%) |

25% (28%) |

11% | [158] | ||

| Asahi Shimbun | 2023 | 72% (80%) |

18% (20%) |

10% | [159] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 42% (54%) |

31% [25% support some rights] (40%) |

22% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 68% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

6% | ±2.75% | [142] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2016 | 7% (7%) |

89% (93%) |

4% | [143] [144] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 9% | 90% (91%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

77% (79%) |

3% | [138] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 36% | 59% | 5% | [146] | ||

| Liechtenstein Institut | 2021 | 72% | 28% | 0% | [160] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 39% | 55% | 6% | [146] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% | 13% | 3% | [146] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 17% | 82% (83%) |

1% | [142] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 74% | 24% | 2% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 55% | 29% [16% support some rights] | 17% not sure | ±3.5%[o] | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (66%) |

32% (34%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Europa Libera Moldova | 2022 | 14% | 86% | [161] | |||

| IPSOS | 2023 | 36% (37%) |

61% (63%) |

3% | [138] | ||

| Lambda | 2017 | 28% (32%) |

60% (68%) |

12% | [162] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 77% | 15% [8% support some rights] | 8% not sure | ±5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 89% (90%) |

10% | 1% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 2% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 70% (78%) |

20% [11% support some rights] (22%) |

9% | ±3.5% | [163] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 25% | 75% | – | ±1.0% | [140] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 2% | 97% (98%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

78% (80%) |

2% | [138] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 72% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

9% | [143] [144] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 22% | 78% | – | ±1.1% | [140] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 26% | 74% | – | ±0.9% | [140] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 36% |

44% [30% support some rights] | 20% | ±5% [o] | [141] | |

| SWS | 2018 | 22% (26%) |

61% (73%) |

16% | [164] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (54%) |

43% (46%) |

6% | [165] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (43%) |

54% (57%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| United Surveys by IBRiS | 2024 | 50% (55%) |

41% (45%) |

9% | [166] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% | 45% | 5% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 80% (84%) |

15% [11% support some rights] (16%) |

5% | [163] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 81% | 14% | 5% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 25% (30%) |

59% [26% support some rights] (70%) |

17% | ±3.5% | [163] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 25% | 69% | 6% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 17% (21%) |

64% [12% support some rights] (79%) |

20% not sure | ±4.8% [o] | [149] | |

| FOM | 2019 | 7% (8%) |

85% (92%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [167] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 9% | 91% | – | ±1.0% | [140] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 11% | 89% | – | ±0.9% | [140] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 4% | 96% | – | ±0.6% | [140] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 24% (25%) |

73% (75%) |

3% | [138] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 33% | 46% [21% support some rights] | 21% | ±5% [o] | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (47%) |

51% (53%) |

4% | [142] | ||

| Focus | 2024 | 36% (38%) |

60% (62%) |

4% | [168] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 37% | 56% | 7% | [146] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 62% (64%) |

37% (36%) |

2% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 53% | 32% [14% support some rights] | 13% | ±5% [o] | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 38% (39%) |

59% (61%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 36% | 37% [16% support some rights] | 27% not sure | ±5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (42%) |

56% (58%) |

3% | [142] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (80%) |

19% [13% support some rights] (21%) |

9% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 87% (90%) |

10% | 3% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 88% (91%) |

9% (10%) |

3% | [146] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 23% (25%) |

69% (75%) |

8% | [142] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 18% | – | – | [147] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 78% (84%) |

15% [8% support some rights] (16%) |

7% not sure | ±5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 92% (94%) |

6% | 2% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 1% | [146] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 54% (61%) |

34% [16% support some rights] (39%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [163] | |

| CNA | 2023 | 63% | 37% | [169] | |||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (51%) |

43% (49%) |

12% | [142] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 58% | 29% [20% support some rights] | 12% not sure | ±5%[o] | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 60% (65%) |

32% (35%) |

8% | [142] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 16% | – | – | [147] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 18% (26%) |

52% [19% support some rights] (74%) |

30% not sure | ±5% [o] | [141] | |

| Rating | 2023 | 37% (47%) |

42% (53%) |

22% | ±1.5% | [170] | |

| YouGov | 2023 | 77% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

8% | [171] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 66% (73%) |

24% [11% support some rights] (27%) |

10% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 74% (77%) |

22% (23%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

32% [14% support some rights] (39%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% | [141] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (65%) |

34% (35%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [142] | |

| LatinoBarómetro | 2023 | 78% (80%) |

20% | 2% | [172] | ||

| Equilibrium Cende | 2023 | 55% (63%) |

32% (37%) |

13% | [173] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [163] |

See also

Notes

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in continental Australia and in the non-self-governing possessions of Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and the Cocos Islands, which follow Australian law.

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in continental Denmark, the Faroe Islands and Greenland, which together make up the Realm of Denmark.

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in metropolitan France and in all French overseas regions and possessions, which follow a single legal code.

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in the continental Netherlands, the Caribbean municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, and the constituent countries of Aruba and Curaçao, but not yet in Sint Maarten.

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in New Zealand proper, but not in its possession of Tokelau, nor in the Cook Islands and Niue, which make up the Realm of New Zealand.

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in all parts of the United Kingdom and in its non-American possessions, but not in its American possessions, namely Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat and the Turks and Caicos Islands.

- Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in all fifty states of the US and in the District of Columbia, in all overseas territories except American Samoa (recognition only), and in all tribal nations that do not have their own marriage laws, as well as in most nations that do. The largest of the dozen or so tribal nations that do not perform or recognize same-sex marriage are Navajo, Gila River and perhaps Yakama, and the largest (or perhaps only) among the shared-sovereignty Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Areas are the Creek, Citizen Potawatomi and Seminole. These polities ban same-sex marriage and do not recognize marriages from other jurisdictions, though members may still marry under state law and be accorded all the rights of marriage under state and federal law.

- Nepal is waiting for a final decision by its supreme court, but meanwhile local governments are ordered to temporarily register same-sex marriages in a separate record. In April 2024 the National ID and Civil Registration Department issued a circular to local governments that they license such marriages. However, simply obtaining marriage certificates does not grant same-sex couples the legal rights of marriage. Some district courts and local government offices are refusing to license same-sex marriages. Comprehensive statistics remain unavailable as these marriages are not being registered into the Department of National ID and Civil Registration's online system.[63][64][65][66][67]

- Dale Carpenter is a prominent spokesman for this view. For a better understanding of this view, see Carpenter's writings at "Dale Carpenter". Independent Gay Forum. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.