Same-sex marriage in tribal nations in the United States

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

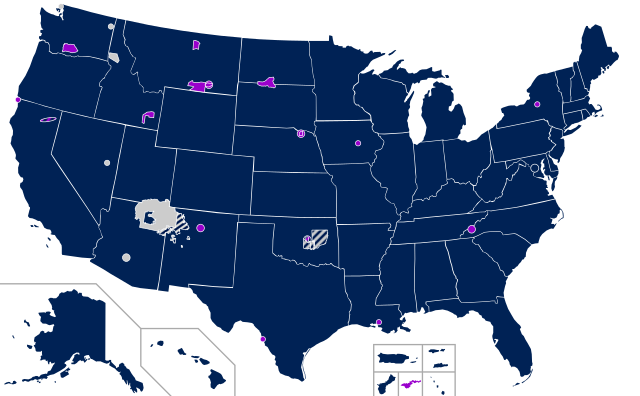

The Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges that legalized same-sex marriage in the states and most territories did not apply on Indian reservations. The decision was based on the equal protection guarantee of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but by long established law, this part of the Constitution does not apply to Indian tribes.[1] Therefore, the individual laws of the various United States federally recognized Native American tribes may set limits on same-sex marriage under their jurisdictions. At least ten reservations specifically prohibit same-sex marriage and do not recognize same-sex marriages performed in other jurisdictions; these reservations remain the only parts of the United States to enforce explicit bans on same-sex couples marrying.

Most federally recognized tribal nations have their own courts and legal codes but do not have separate marriage laws or licensing, relying instead on state law. A few do not have their own courts, relying instead on CFR courts under the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In such cases, same-sex marriage is legal under federal law. Of those that do have their own legislation, most have no special regulation for marriages between people of the same sex or gender, and most accept as valid marriages performed in other jurisdictions. Many Native American belief systems include the two-spirit descriptor for gender variant individuals and accept two-spirited individuals as valid members of their communities, though such traditional values are seldom reflected explicitly in the legal code.[2] Same-sex marriage is possible on at least forty-nine reservations with their own marriage laws, beginning with the Coquille Indian Tribe (Oregon) in 2009. Marriages performed on these reservations were first recognized by the federal government in 2013 after section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was declared unconstitutional in United States v. Windsor.[3] These were statutorily affirmed by the Respect for Marriage Act, which formally repealed DOMA.

Nations that explicitly provide legal recognition

Summarize

Perspective

In some instances, tribal law has been changed to specifically address same-sex marriage. In other cases, tribal law specifies that state law and state jurisdiction govern marriage relations for the tribal jurisdiction.

Ak-Chin Indian Community

Until October 25, 2017, the Ak-Chin Law and Order Code specifically banned same-sex marriages and did not recognize those performed off the reservation.[4]

In September 2015, a member of the Ak-Chin Indian Community filed a lawsuit in the Ak-Chin Indian Community Court, alleging violations of equal protection, the Indian Civil Rights Act and due process, after the tribe refused to recognize her same-sex marriage.[4][5] On October 25, 2017, the court ruled that the law banning same-sex marriage was in violation of the tribe's Constitution and the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. The tribe's chairman announced that the Government will not appeal the ruling. The ruling only applies to the Ak-Chin Indian Community, but may set a precedent for similar future challenges by more tribes.[6]

Bay Mills Indian Community

The Tribal Council of the Bay Mills Indian Community of Michigan legalized same-sex marriage on July 8, 2019,[7][8] by changing its marriage code,[9] removing all wordings which only recognized marriages between a man and a woman.

Previously, the Tribal Code in section 1401 "Recognition of Marriages" stated, "The Bay Mills Indian Community shall recognize as a valid and binding marriage any marriage between a man and a woman formalized or solemnized in compliance with the laws of the jurisdiction in which such marriage was formalized or solemnized." Section 1404.B.1 "Minimum Qualifications of Applicants" stated that "No license for marriage shall be issued by the Tribal Court for a marriage to be performed pursuant to this Chapter unless the applicants for the license shall demonstrate to the Court's satisfaction that: 1. The parties are a man and a woman."[10]

Blackfeet Nation

Chapter 3 of the Law and Order Code of the Blackfeet Nation of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana specifies that state law and state jurisdiction governs marriage relations and that neither common-law nor marriages performed under native customs are valid within the Blackfeet Reservation.[11] On November 19, 2014, US District Court Judge Brian Morris struck down Montana's same-sex marriage ban in Rolando v. Fox.[12] In December 2007, a traditional Blackfoot marriage ceremony was held in Seeley Lake, Montana for a Blackfoot two-spirit couple.[13]

Blue Lake Rancheria

The Blue Lake Rancheria legalized same sex marriage on November 1, 2013 by repealing section 6C of its Marriage Ordinance.[14] Previously, on October 13, 2001, the Business Council of the Rancheria had passed an ordinance which prohibited marriages contracted by same-sex parties. However, section 13 state that marriages legally contracted outside the boundaries of the Blue Lake Rancheria are valid within the tribal jurisdiction.[15]

Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska

The Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida peoples in Alaska voted in February 2015 to legalize same-sex marriage on their sovereign lands. The Council will also be responsible for any related divorces that may arise.[16]

Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation has recognized same-sex marriages since December 9, 2016, overturning a ban established in 2004.[17]

On May 13, 2004, a lesbian couple applied for a marriage license and were approved by a Cherokee Nation tribal court deputy clerk.[18] On May 14, 2004, Judicial Appeals Tribunal Chief Justice Darrell Dowty issued a moratorium on issuing additional same-sex marriage licenses.

On May 18, 2004, the couple were married in Tulsa, but their request to register their certificate of marriage was refused. On June 11, 2004, the Tribal Council's attorney, as a private party, filed an objection to the issuance of the application and on June 16 filed an injunction to nullify the marriage.[19][20] On June 14, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council passed a law banning same-sex marriages.[21] The couple filed a motion for a decision in November 2004. On December 10, their motions to dismiss, quash and for summary judgment were denied by the Cherokee District Court and they appealed to the Judicial Appeals Tribunal of the Cherokee Nation (JAT) on December 17.[22] In June 2005, the JAT set a trial date of August 2 to determine the standing of the Tribal Council attorney to file as a private individual.[23] On August 3, 2005, the JAT ruled that no individual suffered harm from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage and the plaintiff therefore lacked standing.[24]

The following day, 15 tribal councilors filed a petition to prevent the couple from filing their marriage certificate with the tribe.[25] On December 22, the JAT dismissed the injunction again citing the inability of council members to demonstrate that they suffered harm as individuals from the recording of the marriage.[26][27]

On January 6, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Court Administrator filed a petition stating that recording the marriage certificate would violate the tribal law defining marriage as that of a man and a woman.[28] On March 8, the couple filed a motion to dismiss the third challenge as their marriage had occurred prior to the enactment of the law defining marriage as being only between a man and a woman.[29] Though Oklahoma's same-sex marriage ban was overturned on January 14, 2014, in a ruling by U.S. District Judge Terence Kern, the petition before the JAT remained unanswered.[30]

On December 9, 2016, the Attorney General of the Cherokee Nation overturned the tribe's ban on same-sex marriage. His decision took effect immediately. He had been asked to rule on the recognition of same-sex marriage by the tribe's tax commissioner.[17][31] Citing the Cherokee Constitution (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ᎦᎫᏍᏛᏗ, Tsalagihi Ayeli Gagusdvdi), which protects the fundamental right to marry and establish a family, the Attorney General ruled that prohibiting same-sex marriage was unconstitutional.[32]

On March 21, 2017, a Cherokee Nation Rules Committee discussed a proposal that would ask voters whether the tribe should recognize same-sex marriage. The following day, the Council voted to table the resolution indefinitely, keeping same-sex marriage legal.[33]

Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes

Marriage law of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, a united tribe in Oklahoma, makes no specification of the gender of the participants. Based on that, Darren Black Bear and Jason Pickel applied for and received a marriage license on October 18, 2013.[34] Theirs was the third such license issued by the Tribes.[35]

Chickasaw Nation

The Chickasaw Nation Code was amended on April 18, 2022 to allow marriage between any two individuals and repeal language barring recognition of marriages between persons of the same gender. The definition of marriage now reads:

SECTION 6-101.5 DEFINITION OF MARRIAGE, COMMON LAW MARRIAGE.

A. "Marriage" means a personal relation arising out of a civil contract between two individuals to which the consent of parties legally competent of contracting and of entering into it is necessary, and the Marriage relation shall be entered into, maintained or abrogated as provided by law.[36]

Previously, Section 6-101.6.A of the Code, asserted that "'Marriage' means a personal relation arising out of a civil contract between members of the opposite sex to which the consent of parties legally competent of contracting and of entering into it is necessary, and the Marriage relation shall be entered into, maintained or abrogated as provided by law." Section 6-101.9, titled "Marriage Between Persons Of Same Gender Not Recognized", had asserted that "a Marriage between persons of the same gender performed in any jurisdiction shall not be recognized as valid and binding in the Chickasaw Nation as of the date of the Marriage".[37] That section was removed with the 2022 revision.

Choctaw Nation

In May 2023, the Choctaw Constitutional Court ruled that Choctaw Nation members have a right to marry, regardless of gender. The ruling was due to an adoptive couple who were eligible to adopt under federal law under the 14th Amendment but not under tribal law, due to a tribal ban on same-sex marriage; the Choctaw constitution guarantees that tribal members shall not be denied rights provided for by the federal constitution. Choctaw Chief Gary Batton said after the ruling, "Based on this decision, we will review our Codes to see what changes need to be made."[38]

Previously, the Choctaw Nation Marriage Act stated in section 3.1 "Recognition of marriage between persons of same gender prohibited", that "a marriage between persons of the same gender performed in another tribe, a state, or in any other forum shall not be recognized as valid and binding in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma."[39]

As in the other Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Areas governed by one of the "Five Civilized Tribes", all of which are inhabited by a majority non-native population, Choctaw authority only extends to Tribal members and property. Non-members, who do not receive services from the Tribal Government and are not subject to the Tribal Code, were unaffected by the ban on same-sex marriage.

Colorado River Indian Tribes

The Colorado River Indian Tribes of the Colorado River Indian Reservation in California, Nevada and Arizona legalized same-sex marriage on 8 August 2019 by changing section 2-102 of its domestic relations code, stating that a "marriage between two consenting persons licensed, solemnized, and registered as provided in this Chapter is valid".[40] Previously, the code, enacted in 1982, stated that "a marriage between a man and a woman licensed, solemnized, and registered as provided in this Chapter is valid".

Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians

The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians (Coos Bay, Oregon) began recognizing same-sex marriages on August 10, 2014, by repealing part of their marriage law which prohibited same-sex marriages.[41] Previously, section 4-7-6 (c) of the Tribal Code banned same-sex marriage: "No marriage shall be contracted between parties of the same gender." But section 4-7-13 showed a marriage from another jurisdiction could be recognized: "A marriage contracted outside the territory of the Tribes that would be valid by the laws of the jurisdiction in which the marriage was contracted is valid within the territory of the Tribes."[42]

Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians

In March 2013, it was reported that the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians from Oregon had introduced a tribal ordinance to recognize same-sex marriage.[43] The ordinance was proposed when Oregon banned same-sex marriage. The measure was to be an "additional option" for tribal members who would retain the ability to marry through the tribe, the State of Oregon, or their state of residence.[44] On May 16, 2014, the Tribal Council passed a motion in favor of allowing same-sex couples to legally marry on its reservation, but submitted the measure to tribal consultation before implementation. On May 19, 2014, U.S. District Judge Michael McShane ruled that Oregon's ban against same-sex marriage was unconstitutional.[45] On May 15, 2015, the Tribal Council changed its laws to legalize same-sex marriages after 67% of members of the General Assembly voted in favor.[46]

Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in the state of Washington voted for same-sex marriage recognition on September 5, 2013. The vote passed the Tribal Council without objection.[47]

Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon

In October 2015, the Grand Ronde Tribal Council in Oregon passed an ordinance allowing members to marry in the Tribal Court. The ordinance specifically includes a non-discrimination clause that would allow same-sex couples to marry.[48] The ordinance went into effect on November 18, 2015.[49]

Coquille Indian Tribe

In 2008, the Coquille Indian Tribe legalized same-sex marriage, with the law going into effect on May 20, 2009.[50] The law approving same-sex marriage was adopted 5 to 2 by the Coquille Tribal Council and extends all of the tribal benefits of marriage to same-sex couples. To marry under Coquille law, at least one of the spouses must be a member of the tribe.[51] In the 2000 Census, 576 people defined themselves as belonging to the Coquille Nation.

Although Oregon voters approved an amendment to the Oregon Constitution in 2004 to prohibit same-sex marriages, the Coquille are a federally recognized sovereign nation, and thus not bound by the Oregon Constitution.[52] On May 24, 2009, the first same-sex couple—Jeni and Kitzen Branting—married under the Coquille jurisdiction.[50]

Eastern Shoshone Tribe

The first same-sex marriage at the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribal Court (which the Eastern Shoshone Tribe shares with the Northern Arapaho Tribe) on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming was registered on November 14, 2014.[53]

Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

The Tribal Council of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (part of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) approved on July 16, 2014 Ordinance 04/10, which amended "Section 301 Marriage, Domestic Partnership & Divorce" to recognize as valid and binding any marriage between two persons which is formalized or solemnized in compliance with the laws of the place where it was formalized. Chapter 4 recognizes the relationship of two non-married, committed adult partners who have declared themselves as domestic partners provided that it is registered.[54] A member of the Tribal Council explicitly stated that this amendment legalized same-sex-marriage.[55]

Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes

Chapter 5 of the Law and Order Code of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes, enacted on September 13, 1988, provides in section 2 that all marriages from the day of enactment are to be governed by the laws of the states of Nevada or Oregon, depending on which state they occurred in.[56] On May 19, 2014, a federal judge overturned a ban on same-sex marriages in Oregon,[57] and beginning on October 9, 2014 same-sex marriages were allowed in Nevada.[58]

Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation

Chapter 10 of the Law and Order Code of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Community of Arizona states that all marriages since April 19, 1954 "shall be in accordance with state laws".[59] On October 17, 2014, U.S. District Court Judge John Sedwick ruled that Arizona's same-sex marriage ban was unconstitutional.[60]

Grand Portage Band of Chippewa

The Grand Portage Band of Chippewa (part of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) follows state law with regard to marriages as they "do not have jurisdiction over domestic relations" per the Grand Portage Judicial Code.[61] Same-sex marriage was legalized in Minnesota on August 1, 2013, after passage of legislation on May 13, 2013.[62]

Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

The Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan legalized same-sex marriage on May 25, 2022, when the 1998 family law wording (GTB Statutory Law, Title 10, Chapter 5) was changed to "two persons" from "man and wife" and "one man and one woman". The change was explicitly due to the findings of Obergefell v. Hodges.[63]

Hannahville Indian Community

The Hannahville Indian Community in Michigan states in its civil code, enacted on August 3, 2015, that it "recognizes marriage as a legal relationship between persons having the legal capacity to contract marriage under this code, including persons of the same sex".[64]

Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin

On June 5, 2017, the Legislature of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin approved a bill to legalize same-sex marriage, in a 13–0 vote.[65]

Previously, Title 4 of the Ho-Chunk Nation Code (HCC), enacted on October 19, 2004, provided at section 10.3 that marriage is a civil contract requiring consent to create a legal status of husband and wife. Section 10.9 required that a ceremony be solemnized by an officiant, witnessed by two affiants and that the two parties involved agree to becoming husband and wife.[66]

Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel

On June 24, 2013, the Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel announced their recognition of same-sex marriage, becoming the first tribe in California to do so.[67]

Keweenaw Bay Indian Community

On November 7, 2014, the Tribal Council of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community voted to place a referendum on the ballot for a tribal vote on December 13, 2014, to allow same-sex marriage in their community, in response to the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals decision to uphold Michigan's ban on same-sex marriage.[68] The proposal was approved with 302 to 261 votes on December 13, 2014,[69] and finally included into the Tribal Code after the Tribal Council approved the changes on June 6, 2015.[70]

Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Chapter 30 of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Tribal Code provides at section 30.103 that marriages by custom and tradition are not recognized and that legal marriages must be in accord with the laws of the states wherein the marriage is consummated or the laws of Wisconsin. Chapter 30 of the Tribal Code authorizes tribal court judges to perform marriages in accordance with the laws of Wisconsin.[71] On October 6, 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review a decision overturning Wisconsin's ban of same-sex marriages, paving the way for same-sex marriages to begin.[72]

Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe

Title 5, Chapter 2 of the Family Relations Code of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe (part of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) establishes that the tribe has jurisdiction over all marriages performed within its boundaries and over the marriages of all tribal members regardless of where they reside. Chapter 3 defines marriage as a civil contract between two parties who are capable of solemnizing and consenting to marriage. Chapter 2.D.2 provides that "persons within the jurisdiction of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe may contract marriage by declaring in the presence of at least two witnesses who shall sign a declaration that they take each other to be married".[73] On November 15, 2013, the first same-sex marriage took place among the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. The band has the most populous reservation in the state of Minnesota, which had legalized same-sex marriage earlier that year.[74]

Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians

The Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians Tribal Council voted to recognize same-sex marriages on March 5, 2013.[75] The Tribal Chairman signed the legislation on March 15, 2013,[76] and a male couple was married that day. Same-sex marriages entered into by the sovereign tribe are recognized by Michigan, the state where the Little Traverse Bay Bands are based, due to the Supreme Court's ruling striking down Michigan's same-sex marriage ban.[77]

Section 13.102C of the Tribal Code states "Marriage means the legal and voluntary union of two persons to the exclusion of all others."[78]

Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

Since April 29, 2010, the Connecticut-based Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation's law states that "Two persons may be joined in marriage on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation" without specifying gender.[79] This was a change from the 2008 code, which specified that "A man and a woman may be joined in marriage on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation".[80]

In June 2010, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation approved an anti-discrimination ordinance which prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.[81][82]

Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

The Tribal Council of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin approved a marriage law on November 3, 2016, which states under section 6, that marriage "creates a union between two (2) persons, regardless of their sex (or gender)".[83]

Northern Arapaho Tribe

The first same-sex marriage at the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribal Court (which the Northern Arapaho Tribe shares with the Eastern Shoshone Tribe) on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming was registered on November 14, 2014.[53]

Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

The Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi in Michigan enacted a Marriage Code on March 16, 2023, which states in paragraph 7.7-5(A) that the band recognizes "as valid and binding any marriage between two consenting adults without regard to gender, conducted in compliance with the laws of the jurisdiction in which such marriage was formalized".[84] Prior to this they had followed state law.

Oglala Sioux Tribe

Chapter 3 of the Law and Order Code of the Oglala Sioux Tribe provides at section 28 that marriage is a consensual personal relationship arising out of a civil contract, which has been solemnized. Per section 30, any tribal member of legal age, or with parental consent if a minor, may obtain a marriage license from the Agency Office or consummate marriage under authority of license by the state of South Dakota. Voidable or forbidden marriages include incestuous marriages (§31), those obtained if a party is incapable of consent, through fraud, or within prohibited degrees of consanguinity (§32), and those which occur when another spouse is still living (§33).[85] A memorandum by the tribal attorney from January 25, 2016 confirmed that same-sex marriages are not prohibited under the existing Tribal Code. A first same-sex marriage which was conducted by the tribe's chief judge took place soon after. A number of traditional elders voiced their objection against the attorney's viewpoint.[86]

The Child and Family Code (Lakota: Wakanyeja Na Tiwahe Ta Woope), passed by the Tribal Council in 2007, specified that the family unit results of "a union or partnering of a man and a woman".[87]

On July 8, 2019, the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council passed a same-sex marriage ordinance in a 12–3 vote with one abstention, which amended the marital and domestic law on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation that hadn't been changed since 1935.[88]

Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin

The Tribal Code of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin was revised in May 2015, replacing the phrase "husband and wife" with "spouses", explicitly recognizing same-sex marriage. The change came into effect on June 10, 2015.[89]

Osage Nation

The Osage Nation in Oklahoma has explicitly recognized same-sex marriages performed in other jurisdictions since April 6, 2016.[90] On April 20, 2015, Osage Nation Congresswoman Shannon Edwards introduced a same-sex marriage bill.[91] A referendum on whether same-sex marriages should be performed in the reservation took place on March 20, 2017, and the proposal passed, with 770 voting for same-sex marriage and 700 voting against.[92][93] The law took effect immediately.[94]

Previously, on April 12, 2012, at the 4th Session of the 2nd Congress of the Osage Nation, a bill to establish marriage, dissolution and child support procedures for the Osage jurisdiction was passed. At Chapter 2, section 5, marriage was defined as a personal relationship between a man and a woman arising out of a civil contract. Furthermore, section 8 entitled "Marriage Between Persons of Same Gender Not Recognized" provided that same-sex marriages performed in other jurisdictions shall not be recognized as valid by the tribe.[95][better source needed]

Pascua Yaqui Tribe

Title 5, Chapter 2 of the Constitution of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe provides that marriages which are valid at the place where contracted are recognized. Persons 18 and above, or with parental/guardian consent if a minor, shall obtain a license and be joined by an ordained clergyman, minister, or judge.[96] The tribe is located in the state of Arizona, which legalized same-sex marriage on October 17, 2014.[60]

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, in southwestern Michigan and northeastern Indiana, announced on March 9, 2013, that a law recognizing same-sex marriages would enter into force on May 8, 2013.[97] They issued their first such marriage certificate to a male couple on June 20, 2013.[98]

Ponca Tribe of Nebraska

The Domestic Relations Code of the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska states at section 4-2-1.1 that the purpose of that code is to "ensure that couples of the same sex and couples of opposite sex have equal access to marriage".[99] The change was decided by the Tribal Council on a meeting on August 26, 2018.[100] As of 2021, this section had been moved to section 4-2-1.2 with the wording "ensure that couples of the same sex and couples of opposite sex have equal access to marriage and to the protections, responsibilities, and benefits that result from marriage".[101][better source needed]

Previously, Title IV of the Law and Order Code provided that persons may be married who are 18 (or at 16 with parental consent), when at least one of them is a resident tribal member. However, section 4-1-6 required that the parties declare themselves to be husband and wife and that the official pronounce them to be husband and wife. Section 4-1-7 described void marriages as those wherein one party is already married or within prohibited degrees of consanguinity and section 4-1-8 stated that marriages may be voided if any of the parties were unable to or incapable of consent or if consent was obtained through fraud or force.[102]

Section 7-1-4 defines under provision 13 that a domestic partner is "of the same sex or opposite sex". To qualify for limited tribal benefits, a domestic partnership affidavit must be on file with the Tribe.[103]

Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe

The Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe recognized the passage of Washington Referendum 74, which legalized same-sex marriage in Washington. On December 9, 2012, they offered couples the opportunity to marry at Heronswood Botanical Gardens, which is owned by the tribe, near Kingston.[104]

Prairie Island Indian Community

The Minnesota-based Prairie Island Indian Community, which forms a part of the Mdewakanton Dakota, legalized same-sex marriage on March 22, 2017, by changing its Domestic Relations Code. Section 1, Chapter 3c of the Code now states that "two persons of the same or opposite gender may marry".[105] A previous version had explicitly banned same-sex marriages.[106]

Puyallup Tribe of Indians

On July 9, 2014, the Puyallup Tribe of Indians in the state of Washington legalized same-sex marriage.[107]

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community

Chapter 10 of the Tribal Code of Ordinances of the Salt River Pima–Maricopa Indian Community of the Salt River Reservation in Arizona provides that all marriages since April 19, 1954 "shall be in accordance with the state laws".[108] U.S. District Court Judge John Sedwick ruled on October 17, 2014 that Arizona's same-sex marriage ban was unconstitutional.[60]

San Carlos Apache Tribe

According to the Constitution and by-laws of the San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona, all marriages shall be in accordance with state laws.[109] On October 17, 2014, Arizona's ban on same-sex marriage was declared unconstitutional.[60]

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe

The tribal Residency Ordinance, adopted on July 3, 2019, explicitly includes in its definition of marriages (III.7) and spouses (III.22) same-sex marriages for the purpose of the ordinance.[110] In the revision family court code adopted on 21 December 2022, "marriage" is defined as "a contract between two (2) persons, regardless of their sex, creating a union to the exclusion of all others".[111]

In addition, according to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribal Marriage Act of 1995, all marriages that were valid in the place where contracted are recognized by the tribe.[112]

Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan changed its marriage laws on July 7, 2015 by removing gender-specific language and also the need obtain marriage licenses from the state of Michigan before getting married.[113] A spokesperson of the tribe noted that these changes were necessary to legalize same-sex marriage and to exercise tribal sovereignty.[114]

Up to 2015, the law of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians noted that "requirements of the State of Michigan with respect to the qualifications entitling persons to marry within that State's borders, whether now in existence or to become effective in the future, are hereby adopted, both presently and prospectively, in terms of the sex of the parties to the proposed marriage" (Art. 31.104).[115] Same-sex marriage is legal in Michigan. Previously, opposite-sex marriages were recognized by the tribe but the law did not specify whether or not same-sex marriages were recognized.[115]

Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians

On February 2, 2016, the Stockbridge-Munsee Tribal Council in Wisconsin changed its marriage law, stating under section 61.6 g that "Marriage is a civil contract between two (2) persons, regardless of their sex".[116]

Previously, Chapter 61 of the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Tribal Ordinances provided at section 61.2 a definition that marriage is a consensual civil contract which creates the legal status of husband and wife. Section 61.3 states that any person age 18 and above or 16 with consent of a parent or guardian may marry. Invalid or prohibited marriages per section 61.4 are those that would be bigamous, those within prohibited degrees of consanguinity, those in which a party is incapable of understanding a marriage relationship, or those in which one of the parties was divorced within the prior 6 months.[117]

Suquamish Tribe

The Suquamish Tribe of Washington legalized same-sex marriage on August 1, 2011, following a unanimous vote by the Suquamish Tribal Council. At least one member of a same-sex couple has to be an enrolled member of the tribe to be able to marry in the jurisdiction.[118]

Tulalip Tribes of Washington

After changes on May 6, 2016, Chapter 4.20.020(9) of the Tulalip Tribes of Washington's Tribal Code states that marriage is a legal union of two people, regardless of their sex.[119] Previously, Chapter 4.20 of the Code stated at Chapter 4.20.070 that during the ceremony the parties must take each other as husband and wife and the officiant must declare that they are husband and wife.[120]

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota

The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota legalized same-sex marriage on August 6, 2020 by changing the wording of the respective section of the tribal code from "husband and wife" to "spouse".[121]

Previously, the Tribal Code (Title 9 – Domestic Relations) at section 9.0701 defined marriage as a contract between a man and woman which has been licensed, solemnized, and registered. Prohibited marriages per section 9.0707 are those that would result in bigamy or those wherein the parties are within prohibited degrees of consanguinity. However, per section 9.0710, Turtle Mountain recognizes as valid marriages contracted outside its jurisdiction that were valid at the time of the contract or subsequently validated by the laws of the place they were contracted or by the domicile of the parties.[122]

White Mountain Apache Tribe

According to the White Mountain Apache Domestic Relations Code, enacted on September 9, 2015,[123] Chapter 1, sections 1.3, 1.5 and 1.6, marriage is a solemnized civil procedure between consenting parties, of legal age or with parental consent, in conformity with state (Arizona) or tribal law, who are free from infectious and communicable diseases and are not prohibited by clan or specified consanguinity.[124] In a 2017 ruling, an Ak-Chin court noted that the White Mountain Apache Tribe recognizes same-sex marriage.[125]

Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska

The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska Tribal Code (Title Two – Civil Procedure) originally provided that marriages be recorded and in section 2-1202 that tribal members conform to the customs and common law of the Tribe.[126]

After a request by the judicial system to clarify suitability of same-sex marriage under the gender-neutral wording of the code, the tribal council 'narrowly' approved a resolution, on March 24, 2022, to ban same-sex marriage but to allow divorce. After an outcry by members of the community, the resolution was rescinded, with an apology, and on April 11 the council 'overwhelmingly' voted to recognize same-sex marriage and divorce.[127]

Yavapai-Apache Nation

The Domestic Relations Code of the Yavapai-Apache Nation of Arizona of 1994, states in Chapter 3.1. that "all marriages in the future shall be in accordance with the State laws".[128] On October 17, 2014, U.S. District Court Judge John Sedwick ruled that Arizona's same-sex marriage ban was unconstitutional.[60]

Nations that accept marriages performed elsewhere in the state

Summarize

Perspective

Some nations recognize marriages legally performed in other jurisdictions, or the state in which they reside, regardless of whether they may have gendered wording in their own laws. The wording of the legal code suggests the same may be true of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, though recognition of external marriages may be up to the court. An exception to this pattern of blanket external recognition was the Bay Mills Indian Community, which, before July 8, 2019, only accepted marriages between a man and a woman from other jurisdictions. The Lummi Nation states that the marriage license may be obtained from elsewhere in the state, but not explicitly that marriages performed elsewhere in the state are recognized.

Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

Chapter 11, section 1101 of the Tribal Code of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma requires marriages to be recorded for tribal persons regardless of whether they were consummated under tribal custom or in accordance with state law. Section 1102 requires that marriages must conform to the custom and common law of the tribe.[129]

Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

The Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Montana specifies at Chapter 2 of Title 10 of its Family Code that marriages are limited to those of specific degrees of consanguinity. Under section 210, tribal recognition is granted to all marriages "duly licensed and performed under the laws of the United States, any Tribe, state, or foreign nation".[130]

Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians

Chapter 126 of the Tribal Code of the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians provides that tribal procedures shall be concurrent with those established by the laws of Wisconsin. Per section 126.04, those who may not marry are those of prohibited consanguinity, those who are currently married, those who are incapable of assent and those who have been divorced within the last 6 months. However, section 126.13 requires that the parties declare to take each other as husband and wife.[131]

Burns Paiute Tribe of the Burns Paiute Indian Colony

Section 5.1.31(1) of the Tribal Code of the Burns Paiute Tribe (Harney County, Oregon) states that "all marriages performed other than as provided for in this Chapter, which are valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when performed, are valid within the jurisdiction of the Tribe". Section 5.1.34 ("Marriage Ceremony") states that "no particular form of marriage ceremony is required. However, the persons to be married must declare in the presence of the person performing the ceremony, that they take each other as husband and wife, and he must thereafter declare them to be husband and wife.[132]

Cheyenne River Sioux

For the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, Ordinance No. 7 of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Court states that external marriages are declared valid. Section IV Marriage defines marriage as "a personal relation arising out of a civil contract, to which the consent of parties capable of making it is necessary". Section VI states that "any member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe eligible by age and otherwise as hereinafter defined may obtain marriage licenses from the Agency Office". The subsequent conditions do not mention sex, except that the age of consent is different for males and females.

Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana

The Constitution and Comprehensive Codes of Justice of the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana state that for a man and a woman to be married they must be 16 years of age, be able to give consent, or must obtain parental consent. Section 202 prohibits marriages within certain degrees of consanguinity and section 203 prohibits those with existing spouses from marrying. However, the tribe recognizes as valid common-law marriages (section 210) or duly licensed marriage (section 211) which have been recognized as valid under the laws of the United States, any other tribe, state, or foreign nation.[133]

Comanche Nation

Title IV, Chapter 14 of the Comanche Nation Code states "marriage is a personal relation arising out of a civil contract between two legally competent persons. A marriage shall be valid only when commenced or maintained in accordance with any applicable law of the Comanche Nation, any other Indian nation or any state or country". There are no gender requirements.[134]

Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, located in Umatilla County, Oregon, approved in 2007 a law allowing couples, including same-sex couples, to enter a domestic partnership. The possibility of passing same-sex marriage was discussed at the time, but the tribe decided to pass a domestic partnership law instead.[135][full citation needed]

The Family Law Code of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation states:[136]

- Section 2.04 ("Marriage contract; age of parties"): "Marriage is a civil contract entered into by persons at least 18 years of age, who are otherwise capable, and solemnized in accordance with section 2.06."

- Section 2.07 ("Form of solemnization"): "In the solemnization of a marriage no particular form is required except that the parties thereto shall assent or declare in the presence of the person solemnizing the marriage and in the presence of at least two witnesses, that they take each other in marriage."

- Section 2.03(A) ("Other Jurisdictions"): "All marriages performed other than as provided for in the Family Law Code, which are valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when performed, are valid within the jurisdiction of the Confederated Tribes, provided further that they are not also in violation of section 2.08(A) (consanguinity) or 2.08(B) (bigamy). This includes marriages performed in accordance with other Tribe's customs and traditions provided that the Tribe whose customs and traditions are asserted as the basis for a finding of marriage recognizes the marriage as valid."

Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon

Section 331.160 ("Marriages Consummated in Other Jurisdictions") of the Tribal Code Book of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon states that "for the purposes of this Chapter a marriage that is valid and legal in the jurisdiction where consummated shall be valid and legal within the jurisdiction of the Tribal Court." Section 331.150 ("Form of Solemnization – Witnesses") states that "in the solemnizing of a marriage, no particular form is required, except the parties thereto shall assent or declare in the presence of the minister, priest, or Judge solemnizing the same and in the presence of at least two attending witnesses that they each take the other to be husband and wife."[137][138]

Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana

Title VIII ("Domestic Relations") of the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana Judicial Codes provides that marriages must conform to tribal custom, that parties must consent and a ceremony must be performed by an authorized representative in front of witnesses. However, it also states that a "marriage which is valid under the laws of the State of Louisiana shall be recognized as valid for all purposes by the Coushatta Tribe".[139]

Crow Tribe of Montana

The Crow Tribe of Montana's Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act provides at section 10-1-104 that marriage is a consensual relationship between a man and a woman arising out of a civil contract. However, section 10-1-113 states that marriages which are validly contracted under the laws of the place where they occurred are recognized as valid within the Crow Indian Reservation. It further lists specific degrees of consanguinity and marriage before dissolving a prior union as prohibitions to marriage.[140] The Crow Tribe has steadily adopted Christianity over the centuries, and it passed a resolution to its governing documents to "proclaim Jesus Christ as Lord of the Crow Indian Reservation", and thus looks unlikely to legalize same-sex marriage in the Crow Nation in the near future.[141]

Curyung Tribal Council

Title II, Chapter 6 of the Tribal Code of the Curyung Tribal Council provides that the tribe shall uphold the validity of any marriage which was valid under the law of the jurisdiction where it was performed. It also states that any party age 18, under 18 with parental/guardian consent, may marry if they are unmarried and the tribe approves.[142]

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Family law of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (North Carolina) specifies that the marriage between a man and a woman is recognized if a license is obtained from a register of deeds in their county of residence or the Cherokee Court; however, section 50–2 of the Code of Ordinances states that all marriages will be given full faith and credit by the Eastern Cherokee which have been solemnized according to the laws of North Carolina or any other state or Indian nation.[143]

On November 6, 2014, an amendment to Cherokee Code was submitted to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Tribal Council in order to prohibit same-sex marriage in their jurisdiction.[144] On December 11, 2014, the resolution passed, but it simply means marriage ceremonies will not be performed within tribal jurisdiction. Since licenses are issued by the state and since the Eastern Cherokee recognize marriages legally performed elsewhere as valid, recognition is assured.[145]

Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe

The Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe's Law and Order Code, enacted on 8 July 2019, states at section 12-10-090 that marriages entered into outside the tribe's jurisdiction are valid if they are valid in the jurisdiction where they were entered into. Section 12-20 speaks, however, of the rights of "husband and wife".[146]

Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe

The Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe's Law and Order Code provides that all marriages which are valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when they were conducted are valid within the jurisdiction of the Tribe. Section 6-1-6 does not require a specific procedure other than that the spouses must take each other as husband and wife and be declared as same by the officiant. Section 6-1-3 lists specific degrees of consanguinity and bigamy as prohibitions to marriage.[147]

Forest County Potawatomi Community

The Family Law Ordinance of the Forest County Potawatomi Community, enacted on February 9, 2019, declares under section 4.4. that all foreign marriages "shall be recognized by the Tribal Court if valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where the Marriage occurred". Under section 4.1., the code defines marriage as "a legal relationship between two equal persons".[148]

Fort Belknap Indian Community

The Family Court Act of the Fort Belknap Indian Community vests exclusive, original jurisdiction over marriages (and other issues) to the tribal Family Court. Section 1.3.A.1 allows a license to be issued by the Tribal Court or the State of Montana and section 1.3.A.3 provides that a valid marriage exists if a woman and man publicly purport to be wife and husband. Section 2 prohibits marriages wherein one party is already married, within specified degrees of consanguinity, or if the marriage is prohibited by custom of the tribes.[149]

Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma

In 2004, it was reported that the Iowa were one of the few tribes in Oklahoma that defined marriage as between a man and a woman, however, further research has shown that the Iowa Tribal code sections on marriage are gender-neutral, and that no such ban exists.[150] In addition, the Rules of Iowa District Court, Title IV, Chapter 11, section 1101 ("Recording of Marriages and Divorces") states, "All marriages and divorces to which an Indian person in a party, whether consummated in accordance with the State law or in accordance with Tribal law or custom, shall be recorded in writing executed by both parties thereto within three (3) months at the office of the Clerk of the Tribal District Court in the marriage record and a copy thereof delivered to the Bureau of Indian Affairs agency," indicating that outside marriages are recognized.

Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma

Section A.2 of the Marriage and Divorce Ordinance of the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, as revised on February 26, 2011, specifies that marriage must be between parties of the opposite sex. Section A.3 states that a person can only be married to one person of the opposite sex, and Section A.12 prohibits the tribal court from issuing a license or conducting a marriage between people of the same sex. However, Section A.2 also states that "The Court will recognize the following marital relationships as valid: ... (B) Those marriages that are recognized by other jurisdictions, including foreign jurisdictions, that is authenticated by proper documentation that demonstrates consent of a marital relationship."[151]

Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas

Section 19.5 (2) of the Domestic Relationships Code states: "All marriages performed other than as provided for in this Chapter, which are valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when performed, are valid within the jurisdiction of the KTTT."

The tribe does not allow same-sex marriages to be performed in its jurisdictions. Section 19.2 (6) states: "Marriage shall mean a consent relationship between a man and a woman that becomes a civil contract if entered into by two people capable of making the contract. Consent alone does not constitute a marriage. A conventional marriage relies upon the issuance of a license and the issuance of a marriage certificate as authorized by this Chapter. A common-law marriage has no documentary requirements."[152]

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

The Domestic Relations Code of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians at section 9‐1‐2 recognizes all marriages which have been legally consummated in another jurisdiction. Section 9‐1‐4 defines marriage as a personal consensual relationship arising out of a civil contract. Prohibited marriages are those involving incest (section 9‐1‐5) or bigamy (section 9‐1‐6).[153]

Additionally, an opinion by the nation's Assistant Attorney General from May 4, 2016 states that due to its recognition of Mississippi state law (where same-sex marriage has been legal since the Supreme Court ruling in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges) as a "valid means for marriage, same sex marriage is valid in tribal court. Additionally, the tribe will recognize a Mississippi same-sex marriage licence". Furthermore, the tribal court is not prohibited by the current nation's code from issuing same-sex marriage licenses.[154]

Northern Cheyenne Tribe

The Northern Cheyenne Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act defines marriage as a personal, consensual relationship between a man and a woman arising out of a civil contract and requires at section 8-1-10.D that the parties take each other as husband and wife. However, section 8-1-11 ("Existing Marriages") states, "(A) All marriages performed other than as provided for in this Code, which are valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when performed, are valid within the jurisdiction of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation." Prohibited marriages defined at section 8-1-15 include those that would result in bigamy or those of specified degrees of consanguinity.[155]

Omaha Tribe of Nebraska

The Omaha Tribal Code indicates at section 19-1-2.a that all marriages validly performed in the jurisdiction where and when performed are valid. Section 19-1-5 provides that during a ceremony of choice, the parties must take each other as husband and wife and the person performing the ceremony must thereafter declare them to be husband and wife. Void and voidable marriages per section 19-1-6 include those within prohibited degrees of consanguinity, those in which a party had a living spouse and those in which a party is incapable of having sexual relations or was forced or coerced.[156]

Oneida Nation of New York

The Oneida Nation of New York's Marriage Code (amended 2004) provides that a man and a woman may marry if they meet specified requirements. Section 104 states that those who cannot marry are minors, those with a living spouse, and those within prohibited consanguinity. Section 107 does not require a specific ceremony but the parties must declare in the presence of the officiant that they take each other as husband and wife. The Oneida Nation recognizes as valid per section 111 all valid marriages celebrated outside their territorial jurisdiction.[157]

Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma

As of 2005, the Law and Order Code of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma requires marriages to be recorded with the Clerk of the Court "whether consummated in accordance with the State law or in accordance with Tribal law or custom".[158]

Pit River Tribe

According to the Statutes of the Pit River Tribe of California Code, marriage of a man and a woman requires that they are of legal age, or have consent of their parents/guardians, and be capable of consent. Section 203 describes void marriages as those that would result in bigamy or are between prohibited degrees of consanguinity. Section 402 does not specify a type of ceremony other than that in the presence of the judge performing the ceremony, the fiancés must declare that they receive each other as husband and wife. The Pit River Tribal Court shall recognize as valid per section 501 all marriages duly licensed and performed under the laws of the United States, any tribe, state, or foreign nation.[159]

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

According to Title 7, Chapter 1 of the Law and Order Code of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, marriages, whether consummated in accordance with the State law or in accordance with Tribal law or custom, may be recorded by the tribe and that the Tribal Court is the sole authority to determine marital status.[160]

Pueblo of San Ildefonso

The San Ildefonso Pueblo Code provides at section 23.1 that all marriages consummated according to State Law or Tribal custom or tradition are valid. Section 23.4.1 requires licenses be issues to an unmarried male and unmarried female of 18 years or older, or parental permission be obtained. Prohibited marriages per section 23.6 are those which would be bigamous, which are within described degrees of consanguinity, and those which are against tribal custom.[161]

Quapaw Nation

At least for the purpose of the dissolution of marriage, per the Quapaw Tribal Dissolution of Marriage Code adopted on 24 July 2015, "marriage" is defined as "the partnership entered into between two persons as spouses, recognized by the Quapaw Tribal Court or the court where the marriage was consummated". In Part I, Section 4 ("Recognition of Marriage"), it states "any marriage duly licensed and performed under the laws of the United States, any state, or any tribe shall be recognized as valid by the Quapaw Tribe for purposes of this Ordinance".

Sac and Fox Nation

The Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma Code of Laws (Title 13 – Family, Chapter 1 – Marriage & Divorce) requires that marriages consummated in accordance with state law or in accordance with tribal law, which involve a native person, must be recorded with the Clerk of the Tribal District Court.[162]

Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa

Title 6 of the Tribal Code, titled "Family Relations of the Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa", as updated on 30 August 2017, states in Section 6–1203(c), "Same-gender marriages prohibited. Only persons of the opposite gender may marry." However, under Section 6-1205(a) it says, "all marriages performed other than as provided for in this Code, which are valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when performed, are valid within the jurisdiction of the Sac & Fox of the Mississippi in Iowa."[163]

Santee Sioux Nation

The Tribal Code of the Santee Sioux Nation (Title III – Domestic Relations, Chapter 3 – Marriages) provides that a man and a woman can obtain a license on the Santee Sioux Nation Reservation as long as one party is a tribal member, the marriage is performed within the reservation, both parties are at least 18 years old, and all licensing requirements are met. Section 5 states that the tribe recognizes as valid all marriages performed outside the boundaries of the reservation as long as the marriage was legal in the jurisdiction where celebrated.[164]

Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation

The Law and Order Code of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes (Chapter 7 – Domestic Relations) provides that any unmarried male and any unmarried female of the age of 18 years or older, or with parental consent may consent and consummate a marriage. Voidable marriages involve physical incapacity or if consent was obtained by force or fraud, unions breaching prohibited degrees of consanguinity, and marriages that would result in polygamy. Section 2.12 requires that the parties declare in the presence of the officiant that they take each other as husband and wife. However, section 2.2 confirms that all marriages contracted outside of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, which are valid under the law of the state or Country in which they were contracted, are valid in the jurisdiction of the tribe.[165]

Smith River Rancheria

The Smith River Rancheria Domestic Relations Chapter provides at section 5-1-32 that persons seeking to be married must be of the opposite gender and requires at section 5-1-34 the persons to be married must declare in the presence of the person performing the ceremony that they take each other as husband and wife, and he or she must thereafter declare them to be husband and wife. However, under section 5-1-31, the tribe accepts as valid all marriages, including common law and customary marriages, which were lawfully established in the jurisdiction where and when they were contracted.[166]

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

The Law and Order Code of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (Title V – Family Code) provides per section 5–101 that for a man and a woman to be married under this chapter they must be at least 18 years old, or 16 if they have obtained the consent of their parents or guardians, and freely consent themselves. Section 5–102 prohibits marriages within specified degrees of consanguinity and section 5–103 prohibits bigamous marriage. Section 5–109 states that any marriage validly contracted in the United States, any tribe, state, or foreign nation shall be "for all purposes" recognized as valid by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.[167]

Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

The Tribal Code of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community (Title VII – Domestic Relations, Chapter 2 – Marriages) provides that marriage is a consensual personal relationship between two persons arising out of a civil contract. Section 7-02.020 prohibits marriage if one of the parties is currently married and those within specified consanguinity degree. No particular type of ceremony is required but section 7-02.040 stipulates that the parties must take each other to be husband and wife in the presence of a celebrant and two witnesses. Section 7-02.070.A allows that all marriages which were legally valid under the laws of the jurisdiction where and when contracted are valid within the tribal jurisdiction.[168]

Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California

The Tribal Code of the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California at section 9-10-090 recognizes marriages contracted outside its jurisdiction as valid within its jurisdiction if they are valid in the jurisdiction in which they were contracted.[169]

Yomba Shoshone Tribe

The Law and Order Code of the Yomba Shoshone Tribe holds at section A2 that for a marriage to be valid both parties must consent and section A3 states that any party 16 and older with consent, or any party 18 or above, who does not lack mental capacity or impairment due to substances may marry. Section A5e requires that a certificate containing a statement that the parties consent to the establishment of the relationship of husband and wife must be signed by the parties, the officiant and two witnesses. Section A7 confirms that marriages entered into outside the tribal jurisdiction will be considered valid by the tribe, if they were valid where obtained. Section B2 provides that marriages entered into under tribal custom are valid.[170]

Nations that have same-sex marriage under federal courts

Summarize

Perspective

Several courts operate under federal law through the Bureau of Indian Affairs: "Courts of Indian Offenses are established throughout the U.S. under the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), providing the commonly used name — the 'CFR Court'. Until such time as a particular Indian tribe establishes their own tribal court, the Court of Indian Offenses will act as a tribe's judicial system."[171] Under federal law, same-sex marriage is legal for these Tribes, despite the wording of the CFR specifying that a license shall be issued "upon written application of an unmarried male and unmarried female".

As updated to October 27, 2016, CFR courts are established for the following Tribal jurisdictions:[172]

- Santa Fe Indian School Property, including the Santa Fe Indian Health Hospital, and the Albuquerque Indian School Property (land held in trust for the 19 Pueblos of New Mexico)

- Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians (Utah)

- Te-Moak Band of Western Shoshone Indians of Nevada

- Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (Colorado)

- Winnemucca Indian Tribe (Nevada)[173]

- Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

- Caddo Nation of Oklahoma

Delaware Nation[off the list by 2023][174][175]- Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

- Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma

- Otoe-Missouria Tribe of Indians

- Wichita and Affiliated Tribes of Indians

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma

- Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma

"Within the exterior boundaries" of the Wind River Reservation (Wyoming)[off the list by 2023]

The 2013 revision of this list noted that five tribes had left since the previous revision: Wyandotte Tribe of Oklahoma, Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Miami Tribe, and Quapaw Tribe of Indians. At least the Seminole and Choctaw enacted codes that banned same-sex marriage, however same-sex marriage has since become legal in the Choctaw Nation. The Comanche Nation (except for the children's court) was listed in the 2016 update, but as of 2019 was no longer under CFR.

Nations with gender-neutral language

Summarize

Perspective

The marriage codes of some nations use gender-neutral language for the couple getting married, such as "persons" or "tribal members." If a case has not yet come up to establish a precedent, the court clerk will generally say that all one can do is read the code, and that lack of prohibition indicates that same-sex marriage should be legal. However, codes may also refer to tribal customs for marriage, without specifying what that might mean. In a few cases, sex is only specified for differing ages of consent. Some codes do not provide for marriage at all, only for its nullification, suggesting that marriages might be performed under state law.

Chippewa Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy's Reservation

The Chippewa Cree of the Rocky Boy's Reservation in Montana have traditionally respected variant identities.[176] Their Law and Order Code of 1987 (Title 5 – Domestic Relations, Chapter 1 – Marriages) prohibits marriages when one party is currently married, when the specified degree of consanguinity is breached, or when the marriage does not conform with tribal custom or tradition.[177]

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation

The minutes of a tribal council meeting which took place on 20 December 2016 stated that the "... Code is silent on defining who can marry. If the Tribal Code is silent, then we rely on federal law first and then state law."[178] The Codified Laws of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (revised on April 15, 2003) specify in Title III, Chapter 1 that the Tribal Court shall have jurisdiction over all marriages of Indians residing on the Flathead Reservation and other consenting parties and that tribal judges or the Tribal Court are authorized to perform ceremonies.[179]

Hopi Indian Tribe

The Hopi Law and Order Code does include a marriage section. However, the Hopi Parental Responsibility Ordinance defines "'marriage' as an institution according to any practice recognized under Hopi law, including marriage according custom and tradition where sufficient evidence of such marriage is presented to the Hopi courts."[180]

Karuk Tribe

The Children and Family Code of the Karuk Tribe defines marriage in section 3A as "a personal relationship between two (2) persons arising out of a civil contract to which the consent of the parties is essential". Only marriages between persons who are already married or closely related are considered illegal under section 3B.[181]

The Tribal Employment Rights Ordinance and Workforce Protection Act, adopted on April 8, 2013, provides at section 1.3.ee that "spouse" is defined as a party, widow, or widower to a marriage, other than a common law union, to a Tribal member recognized by any jurisdiction. Section 4.1 bans discrimination in employment for a variety of reasons, including sexual orientation and section 4.9.a.5a bars discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in relation to employment, labor or licensing.[182]

Poarch Band of Creeks

The Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Domestic Code states that licenses may be issued to tribal members and requires that parties be of legal age. Section 15-1-7 describes void marriages as those wherein one party is already married or within prohibited degrees of consanguinity and section 15-1-8 states that marriages may be voided if any of the parties were unable to or incapable of consent, if consent was obtained through fraud or force, or if the marriage cannot be consummated.[183]

Rosebud Sioux Tribe

The Law and Order Code of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe (Title 2 – Domestic Relations, Chapter 4 – Marriage of Tribal Members) provides that the tribe assumes jurisdiction on marriage between tribal members, that the tribe and tribal courts are not impeded from recognizing marriages validly entered into in other jurisdictions, and follow tribal custom and tradition "without requirements of oath, affirmation or ceremony or involvement of religious or civil authority."[184]

Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe

The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe Family Code establishes that actions arising under the customs and traditions of the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe affecting family and child welfare are within the jurisdiction of the Sauk-Suiattle Family Court. No particular marriage guidelines are stated; however, section 3.2.010 defines "spouse" to include common law spouses, which for purposes of this code are "parties to a marriage recognized under tribal custom or parties to a relationship wherein the couple reside together and intend to reside together as a family."[185]

Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe

The Code of Laws of the Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe (Title 20-Family) has no provisions for performing marriage ceremonies. At section 20.10.060, it provides that a marriage may be invalidated by the Court if it finds that it was contracted by minor party(ies), bigamous, capacity to consent was lacking, prohibited consanguinity existed, or the physical relationship associated with marriage which the parties did not agree to at or prior to the time of entering into the marriage has been lost.[186]

Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation

The Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Code of Law (Chapter 34 – Domestic Relations) at section 34.4.01 defines marriage as a personal consensual relationship arising out of a civil contract which has been solemnized. "A marriage may be solemnized by any recognized clergyman or Judge within the jurisdiction of the Indian Reservation only after issuance of a license." Section 34.6 states that, (1) Any member of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Tribe or other Indian Tribe, eligible by age and otherwise as hereinafter defined, may obtain a marriage license from the Clerk of the Court, and marriages consummated by authority of such license shall be deemed legal in every respect. (2) Prior to the performance of any marriage ceremony, the Judge of the Tribal Court shall examine the compatibility, age, sex, health, blood relationship, and other pertinent matters of the applicants for marriage. After said examination, the Judge shall determine whether the requisites for marriage have been met. Thus sex is considered a qualifying aspect for marriage, but acceptance is up to the judge.

Voidable marriages according to section 34.7.01 include those in which there is incapacity to consent or those in which consent was obtained by force or fraud and defines illegal marriages at section 34.8.01 as those which would result in bigamy.[187]

Tohono O'odham Nation of Arizona

Title 9, Chapter 1 of the Tohono O'odham Nation (previously known as Papago Law and Order Code Chapter 3, "Domestic Relations") provides that duly licensed applicants over the age of 21, if male, and 18, if female (or with parental consent if a minor), can be married by authorized officiants. Prohibited marriages per section 7 are limited to those within listed degrees of consanguinity.[188]

White Earth Nation

The Family Relations Code of the White Earth Nation (part of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) defines only marriages which are voidable. Those include per section 3.1.a bigamous marriages, those entered into by minors, and those prohibited by degrees of consanguinity. Under section 3.2, a marriage could be declared voidable if the party lacked capacity to consent, consummate the marriage, or was under age at the time it was entered into.[189]

Yurok Tribe

The Tribal Code of the Yurok Tribe defines marriage as the union of two individuals by any ceremony or practice recognized under Yurok law, section 3.1 states that "typically any two persons may marry". Under prohibited unions in section 3.2, the only impediments are a living spouse or a relative within specific degrees of consanguinity.[190]

Nations that may have same-sex marriage

Summarize

Perspective

The information available for the federally recognized Native American tribes in this section is suggestive of same-sex marriage but does not fit clearly into one of the above categories. Some recognize same-sex marriage for specific benefits, or domestic partnerships, but the marriage laws (if any) are not indicated in the source.

Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians

The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians operates resorts and casinos in Palm Springs and Rancho Mirage in California. Employees have access to same-sex benefits for domestic partners and as of January 2014 the tribe began offering coverage to employees in same-sex marriages.[191]

Cabazon Band of Mission Indians

The Cabazon Band of Mission Indians operates the Fantasy Springs Resort Casino in Indio and offers employment benefits for domestic partners.[192]

Hoh Indian Tribe

The Hoh Indian Tribe's Housing Management Policy which was adopted on January 15, 2015 defines marriage as "a marriage acknowledged in any state or tribal jurisdiction, same-sex and common-law marriages."[193] The tribe's Code of Conduct, Core Values and Ethical Standards at section 18 prohibits harassment or discrimination on the basis of an individual's sex, marital status or sexual orientation, among other listed items.[194]

Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe

The Labor Code of the Tribal Code for the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe under section 3.06.05.D.9 provides that the Tribal Family Medical Leave can be extended to care for domestic partners in the same manner as spouses, as long as the employee has registered their domestic partnership and the name of their domestic partner with the Human Resources Director.[195]

Mohegan Indian Tribe of Connecticut

The Mohegan Sun, a casino located in Uncasville in Connecticut and operated by the Mohegan Indian Tribe has offered domestic partners and dependents of full and part-time employees benefits since March 2001. Since Connecticut's recognition of same-sex marriage in November 2008, these benefits have been extended to same-sex married partners.[192]

Morongo Band of Mission Indians

The Morongo Band of Mission Indians, which runs a tribal casino and hotel in Cabazon in California provides to all employees and their legal spouses, whether same-sex or opposite-sex, health, retirement and other benefits.[191]

Penobscot Nation

During debates in 2009 for the passage of Maine's same-sex marriage legislation, Representative Wayne Mitchell of the Penobscot Nation, who was unable to vote as a tribal representative, urged House members to pass the bill.[196]

Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians

The Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians in California started an ad campaign in November 2008 offering same-sex wedding packages in the nation-owned casino.[197]

Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians

The Workers' Compensation Ordinance for Tribal Employees of the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians provides that a "spouse" can be a member of the same sex if the members have cohabited for one year as if they were married prior to any occurrence of injury and are registered at the time of any injury with the State of California Secretary of States' Domestic Partners Registry.[198]

Snoqualmie Indian Tribe

In the Funeral Assistance Code of the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe is a provision defining domestic partners as two adults of the same or opposite sex.[199]

Squaxin Island Tribe

Title 8 of the Probate Code of the Squaxin Island Tribal Code defines spouse as "individuals married to, or registered as a domestic partnership with, the decedent and common law spouses, the latter of which means parties to a marriage that is recognized under Tribal custom or parties to a relationship wherein the couple reside together and intend to reside together as a family."[200] The tribal Legal Department Policies and Procedures, Eligibility, Admission and Occupancy Policy defines marriage as an acknowledged marriage in any state or tribal jurisdiction, same-sex, and common law marriages.[201]

Nations that use generic gendered phrasing (no mention of other jurisdictions)

Summarize

Perspective

The wording of many marriage codes do not explicitly include or exclude same-sex marriage but contain conventionalized heterosexual wording such as affirming that the couple are to be "husband and wife." Such wording, if taken literally, would preclude same-sex marriage. However, the definition of marriage in such codes, and the itemized qualifications for who may marry, are in many cases gender-neutral, and some accounts describe the codes as a whole as gender-neutral. In many cases, the gendered wording dates to a time before same-sex marriage was an issue, suggesting they may simply be conventionalized phrases equivalent to "joined in marriage". A question of language rights also occurs, of whether the English of the legal code trumps the traditional language of the nation. In Cherokee, for example, the words that correspond to English "husband and wife" translate literally as "companion [that I live with] and cooker", which have been argued to be gender neutral.[202] In addition, if the law states that the couple must declare themselves to be "husband and wife", or to be declared "husband and wife," it may not be clear what would happen if the letter of the law were followed by using that wording for a same-sex couple.

Hoopa Valley Tribe

The Domestic Code of the Hoopa Valley Tribe in section 14A.2.10 states that two consenting persons over the age of 18 may marry if they have lived within reservation boundaries for 90 days. In section 14A.2.20, the only prohibited marital unions are specific degrees of consanguinity and a current living spouse. However, section 14A.2.40 requires the persons to be married to declare taking each other as husband and wife in the presence of the celebrant and at least two witnesses.[203]

Nisqually Indian Tribe

The Tribal Code of the Nisqually Indian Tribe (Title 11 – Domestic Relations) provides that the marriage ceremony chosen by the persons who are marrying may be conducted in any reasonable manner, provided they verbally agree to be husband and wife.[204]

Spirit Lake Tribe

The Spirit Lake Tribe Law and Order Code, as amended by Resolution A05-04-159 adopted on July 28, 2004, states at section 9-1-101 that marriages consummated by tribal custom are valid and legal. Section 9-1-105 requires that the parties must declare in the presence of the officiant, that they take each other as husband and wife, and must be declared by the officiant to be husband and wife. Void and voidable marriages per section 9-1-106 are those within prohibited degrees of consanguinity and those contracted when a party has a currently living spouse.[205]

Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation

Title V of the Law and Order Code of the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation provides that persons 14 and above with parental consent, of whom one of the parties is a tribal member, who are free of venereal disease may marry. Section 5-1-6 defines void and voidable marriages as those obtained by force or fraud, when a party was already legally married or when a prohibited degree of consanguinity existed. Section 5-1-5 requires the parties to declare that they are husband and wife in the presence of an official.[206]

Yankton Sioux Tribe

Title VII of the Yankton Sioux Tribal Code provides in section 7-1-3 that persons 14 and above with parental consent, of whom one of the parties is a tribal member, who are free of venereal disease may marry. Section 7-1-5 requires that they take each other as husband and wife and are declared to be husband and wife by the celebrant. Section 7-1-6 lists voidable marriages as those in which one party was already married or within prohibited degrees of consanguinity.[207]

Nations that may ban same-sex marriage

Summarize

Perspective

Several nations specify that marriage is between a man and a woman, and no mention is made of accepting external marriages as valid. Gila River (next section) confirmed that such wording was to be taken at face value.

Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation

The 2009 Tribal Code of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation (Title XXII, section 22.01.05) states, "A valid marriage hereunder shall be constituted by: (1) The issuance of a marriage license by the Tribal Court or other lawful issuing agency." Section 22.01.07 states, "A marriage license shall be issued by the Clerk of the Court ... upon written application of an unmarried male and unmarried female." Section 22.01.11 states, "Marriages which are prohibited or invalid under this Code are: (3) When marriages are prohibited by custom and usages of the Tribe."