Libyan civil war (2014–2020)

Armed conflict in Libya From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Libyan Civil War (2014–2020), also known as the Second Libyan Civil War, was a multilateral civil war which was fought in Libya among a number of armed groups, but mainly the House of Representatives (HoR) and the Government of National Accord (GNA), for six years from 2014 to 2020.[124]

| Second Libyan Civil War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Winter, the Libyan Crisis, the Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict, the War on terror, and the Qatar–Saudi Arabia diplomatic conflict | |||||||||

Military situation in Libya on 11 June 2020 Under the control of the Government of National Accord (GNA) and different militias forming the Libya Shield Force Controlled by local forces

(For a more detailed map, see military situation in the Libyan Civil War) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Main belligerents | |||||||||

|

House of Representatives (Tobruk-based)[2][3]

Others:

|

Government of National Accord (Tripoli-based) (from 2016)

Others:

Turkey (2020)[63][64][65] Support: National Salvation Government |

Islamic State al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (2014–2017)[102] Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries (2014–2017)[103][104] SCBR militia:

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Aguila Saleh Issa (President of House of Representatives) Abdullah al-Thani (Prime Minister)[109] Khalifa Haftar (High Commander of the LNA) Abdulrazek al-Nadoori (Chief of the General Staff of the LNA) Wanis Abu Khamada (Commander of Libyan Special Forces) Almabrook Suhban (Chief of Staff of the Libyan Ground Forces) Saqr Geroushi (Chief of Staff of the Libyan Air Force) (LNA-aligned) Faraj al-Mahdawi (Chief of Staff of the Libyan Navy) (LNA-aligned) Saif al-Islam Gaddafi (Candidate for President of Libya) Tayeb El-Safi (leader of Libyan Popular National Movement) Aladdin Meier (political secretary) |

Fayez al-Sarraj Nouri Abusahmain (2014–16) (President of the GNC) Khalifa al-Ghawil (2015–2017) (Prime Minister)[110] Sadiq Al-Ghariani (Grand Mufti) |

Abu Nabil al-Anbari † (Top ISIL leader in Libya)[111][112] Abu Khalid al Madani † (Former Ansar al-Sharia Leader) Ateyah Al-Shaari DMSC / DPF leader Wissam Ben Hamid †[117] (Libya Shield 1 Commander) Salim Derby † (Commander of Abu Salim Martyrs Brigade)[118] | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 14,882+ killed (2014–2018, 2019–2020, incomplete)[119][120][121][122][123] | |||||||||

The General National Congress (GNC), based in western Libya and backed by various militias with some support from Qatar and Turkey,[125][126][127][128][excessive citations] initially accepted the results of the 2014 election, but rejected them after the Supreme Constitutional Court nullified an amendment regarding the roadmap for Libya's transition and HoR elections.[13] The House of Representatives (or Council of Deputies) is in control of eastern and central Libya and has the loyalty of the Libyan National Army (LNA), and has been supported by airstrikes by Egypt and the UAE.[125] Due to controversy about constitutional amendments, HoR refused to take office from GNC in Tripoli,[129] which was controlled by armed Islamist groups from Misrata. Instead, HoR established its parliament in Tobruk, which is controlled by General Haftar's forces. In December 2015, the Libyan Political Agreement[130] was signed after talks in Skhirat, as the result of protracted negotiations between rival political camps based in Tripoli, Tobruk, and elsewhere which agreed to unite as the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA). On 30 March 2016, Fayez Sarraj, the head of GNA, arrived in Tripoli and began working from there despite opposition from GNC.[131]

In addition to those three factions, there are: the Islamist Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries, led by Ansar al-Sharia, which had the support of the GNC and was defeated in Benghazi in 2017;[132][133][134] the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant's (ISIL's) Libyan provinces;[135] the Shura Council of Mujahideen in Derna which expelled ISIL from Derna in July 2015 and was later itself defeated in Derna by the Tobruk government in 2018;[136] as well as other armed groups and militias whose allegiances often change.[125]

In May 2016, GNA and GNC launched a joint offensive to capture areas in and around Sirte from ISIL. This offensive resulted in ISIL losing control of all significant territories previously held in Libya.[137][138] Later in 2016, forces loyal to Khalifa al-Ghawil attempted a coup d'état against Fayez al-Sarraj and the Presidential Council of GNA.[139]

On 4 April 2019, Khalifa Haftar, the commander of the Libyan National Army, called on his military forces to advance on Tripoli, the capital of the GNA, in the 2019–20 Western Libya campaign[140] This was met with reproach from United Nations Secretary General António Guterres and the United Nations Security Council.[141][142]

On 23 October 2020, the 5+5 Joint Libyan Military Commission representing the LNA and the GNA reached a "permanent ceasefire agreement in all areas of Libya". The agreement, effective immediately, required that all foreign fighters leave Libya within three months while a joint police force would patrol disputed areas. The first commercial flight between Tripoli and Benghazi took place that same day.[143][144] On 10 March 2021, an interim unity government was formed, which was slated to remain in place until the next Libyan presidential election scheduled for 24 December that year.[1] However, the election has been delayed several times[145][146][147] since, effectively rendering the unity government in power indefinitely, causing tensions which threaten to reignite the war.[67][68][35][28][29]

Background of discontent with General National Congress

Summarize

Perspective

At the beginning of 2014, Libya was governed by the General National Congress (GNC), which won the popular vote in 2012 elections. The GNC was made of two major political groups, the National Forces Alliance (NFC) and the Justice and Construction Party (JCP). The two major groups in parliament had failed to reach political compromises on the larger more important issues that the GNC faced.

Division among these parties, the row over the political isolation law, and a continuous unstable security situation greatly impacted the GNC's ability to deliver real progress towards a new constitution for Libya which was a primary task for this governing body.[148]

The GNC also included members associated with conservative Islamist groups as well as revolutionary groups (thuwwar). Some members of the GNC had a conflict of interest due to associations with militias and were accused of channeling government funds towards armed groups and allowing others to conduct assassinations and kidnappings. Parties holding majority of seats and some holding minority of seats began to use boycotts or threats of boycotts which increased division and suppressed relevant debates by removing them from the congressional agenda;[149] voting to declare sharia law and establishing a special committee to "review all existing laws to guarantee they comply with Islamic law";[150] imposing gender segregation and compulsory hijab at Libyan universities; and refusing to hold new elections when its electoral mandate expired in January 2014[151] until General Khalifa Haftar launched a large-scale military offensive against the Islamists in May 2014, code-named Operation Dignity (Arabic: عملية الكرامة; 'Amaliyat al-Karamah).[152][153]

Political fragmentation of the GNC

The 2012 elections, overseen by the Libyan electoral commission with the support of the UN Special Mission In Libya (UNSMIL) and nongovernmental organizations like the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), have been considered "fair and free" by most Libyans. However, the elections did not necessarily create a strong government because the Parliament was fragmented due to the lack of organized political parties in Libya post-revolution. The GNC was made up of two major parties, the National Forces Alliance and the Justice and Construction Party, as well as independents in which some were moderates and other conservative Islamists. The GNC became a broad-based congress.[148]

The GNA elected Nouri Abusahmain as president of the GNC in June 2013.[154][155] He was considered an independent Islamist and a compromise candidate acceptable to liberal members of the congress, as he was elected with 96 out of a total of 184 votes by the GNC.[156]

Libya Revolutionaries Operations Room and kidnapping of Ali Zeidan

The GNC was challenged due to increasing security concerns in Tripoli. The GNC itself was attacked many times by militias and armed protesters who stormed the GNC assembly hall.[157] Following his appointment, Abusahmain was tasked with providing security. He set up the Libya Revolutionaries Operations Room (LROR), which was made up of rebels from Gharyan, and was initially intended to protect and secure Tripoli in August 2013. Its commander was Adel Gharyani. During this time, Abusahmain blocked inquiries into the distribution of state funds and it was alleged that Abusahmain was channeling government funding towards the LROR.[156]

In October, Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan was kidnapped. It is believed to have been carried out by the LROR,[158] although there is evidence to suggest that armed groups such as the Duru3 actually conducted the kidnapping.[159] Following the kidnapping, Abusahmain used his presidency to change the agenda of the GNC in order to prevent them from disestablishing the LROR. At the same time, he cancelled a request to establish a committee to investigate his allocation of 900 million Libyan Dinars (US$720 million) to the LROR and various other armed groups.[149]

The GNC responded by removing Abusahmain as president and dismissing the LROR from its security function.[160] However, the armed group was allowed to continue to operate, and no one was prosecuted for the incident.

Expansion of armed groups during the GNC's term

Many Libyans blamed the GNC and the interim government for a continued lack of security in the country. The interim government struggled to control well-armed militias and armed groups that established during the revolution. Libyans in Benghazi especially began to witness assassinations and kidnapping and perceived the GNC to be turning a blind eye to the deteriorating security situation in the east.

But security concerns increased across the country, allowing armed groups to expand in Tripoli and the east.

- In 2012, the assassination of the US ambassador to Libya by Ansar al-Sharia took place.[161]

- In October 2013, the kidnapping of Prime Minister Ali Zeidan by the LROR took place.

- The kidnapping of Egyptian diplomats in January 2014 also by the LROR took place.

- In March 2014, armed protesters allegedly linked to the LROR stormed the GNC parliament building, shooting and injuring two lawmakers and wounding several others.[157]

In April 2014, an anti-terrorist training base called "Camp 27", located between Tripoli and the Tunisian border, was taken over by forces fighting under the control of Abd al-Muhsin Al-Libi, also known as Ibrahim Tantoush,[162] a long-serving Al-Qaeda organizer and former member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group.[163] The Islamist forces at Camp 27 have subsequently been described as part of the Libya Shield Force.[164] The Libya Shield Force was already identified by some observers as linked to al-Qaeda as early as 2012.[165][166]

GNC's political isolation law

Although Islamists were outnumbered by Liberals and Centrists in the GNC, in May 2013 they lobbied for a law "banning virtually everyone who had participated in Gaddafi's government from holding public office". While several Islamist political parties and independents supported the law, as they generally had no associations to the Gaddafi regime, the law enjoyed strong public support.

The law particularly impacts elite expatriates and leaders of liberal parties. There existed reservations that such a law would eliminate technocratic expertise needed in Libya at the time.

Armed militiamen stormed government ministries, shut down the GNC itself and demanded the law's passage. This intimidated the GNC into passing the law in which 164 members approved the bill, with only four abstaining and no member opposing it.[148]

Suppression of women's rights

GNC opponents argue that it was supporting Islamist actions against women. Sadiq Ghariani, the Grand Mufti of Libya, is perceived to be linked closely to Islamist parties. He has issued fatwas ordering Muslims to obey the GNC,[167] and fatwas ordering Muslims to fight against Haftar's forces[168]

In March 2013, Sadiq Ghariani, issued a fatwa against the UN Report on Violence Against Women and Girls. He condemned the UN report for "advocating immorality and indecency in addition to rebelliousness against religion and clear objections to the laws contained in the Quran and Sunnah".[169] Soon after the Grand Mufti issued a clarification op-ed that there should be no discrimination between men and women yet women have a greater role in the family.[170]

Later in 2013, lawyer Hamida Al-Hadi Al-Asfar, advocate of women's rights, was abducted, tortured and killed. It is alleged she was targeted for criticising the Grand Mufti's declaration.[171] No arrests were made.

In June 2013, two politicians, Ali Tekbali and Fathi Sager, appeared in court for "insulting Islam" for publishing a cartoon promoting women's rights.[172] Under sharia law they were facing a possible death penalty.[citation needed] The case caused widespread concern although they were eventually acquitted in March 2014. After the GNC was forced to accept new elections, Ali Tekbali was elected to the new House of Representatives.[citation needed]

During Nouri Abusahmain's presidency of the GNC and subsequent to GNC's decision to enforce sharia law in December 2013, gender segregation and compulsory hijab were being imposed in Libyan universities from early 2014, provoking strong criticism from Women's Rights groups.

A Netherlands-based global advocacy organization, Cordaid, reported that violence against Libyan women at the hands of militias frequently goes unpunished. Cordaid also noted that restricted freedom of movement, driven by fear of violence, has led to declines in schooling among women and girls.[173]

GNC extends its mandate without elections

The GNC failed to stand down at the end of its electoral mandate in January 2014, unilaterally voting on 23 December 2013 to extend its power for at least one year. This caused widespread unease and some protests. Residents of the eastern city of Shahat, along with protesters from Bayda and Sousse, staged a large demonstration, rejecting the GNC's extension plan and demanding the resignation of the congress followed by a peaceful power transition to a legitimate body. They also protested the lack of security, blaming the GNC for failing to build the army and police.[152] Other Libyans rejecting the proposed mandate rallied in Tripoli's Martyrs Square and outside Benghazi's Tibesti Hotel, calling for the freeze of political parties and the re-activation of the country's security system.[174]

On 14 February 2014, General Khalifa Haftar ordered the GNC to dissolve and called for the formation of a caretaker government committee to oversee new elections. However, his actions had little effect on the GNC, which called his actions "an attempted coup" and called Haftar himself "ridiculous" and labelled him an aspiring dictator. The GNC continued to operate as before. No arrests were made. Haftar launched Operation Dignity three months later on 16 May.[175]

House of Representatives versus GNC

On 25 May 2014, about one week after Khalifa Haftar started his "Operation Dignity" offensive against the General National Congress, that body set 25 June 2014 as the date for new elections.[176] Islamists were defeated, but rejected the results of the election, which saw only an 18% turnout.[177][178] They accused the new House of Representatives parliament of being dominated by supporters of Gaddafi, and they continued to support the old GNC after the Council officially replaced it on 4 August 2014.[125][179]

The conflict escalated on 13 July 2014, when Tripoli's Islamists and Misratan militias launched "Operation Libya Dawn" to seize Tripoli International Airport, capturing it from the Zintan militia on 23 August. Shortly thereafter, members of the GNC, who had rejected the June election, reconvened as a new General National Congress and voted themselves as replacement of the newly elected House of Representatives, with Tripoli as their political capital, Nouri Abusahmain as president and Omar al-Hasi as prime minister. As a consequence, the majority of the House of Representatives were forced to relocate to Tobruk, aligning themselves with Haftar's forces and eventually nominating him army chief.[180] On 6 November, the supreme court in Tripoli, dominated by the new GNC, declared the House of Representatives dissolved.[181][182] The House of Representatives rejected this ruling as made "under threat".[183]

On 16 January 2015, the Operation Dignity and Operation Libya Dawn factions agreed on a ceasefire.[184] The country was then led by two separate governments, with Tripoli and Misrata controlled by forces loyal to Libya Dawn and the new GNC in Tripoli, while the international community recognized Abdullah al-Thani's government and its parliament in Tobruk.[185] Benghazi remained contested between pro-Haftar forces and radical Islamists.[186]

Opposing forces

Summarize

Perspective

Pro-GNC

The pro-GNC forces were a coalition of different militias with different ideologies although most of them are Islamist influenced especially in eastern Libya in Benghazi and Derna. Since LPA negotiations started in Skhirat there has been a rift within the militias over support for the UN-sponsored talks and the proposed Government of National Accord, which seeks to unite the rival governments.[187]

Since GNA started working from Tripoli in March 2015, Libya Dawn coalition the largest of Pro-GNC militias has been disbanded and most of its forces changed allegiances to GNA.[188]

Libya Dawn

The Islamist "Libya Dawn" has been described as "an uneasy coalition" identified as "terrorists" by the elected parliament in Tobruk[189] including "former al-Qaeda jihadists" who fought against Gaddafi in the 1990s, members of Libya's branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, and a "network of conservative merchants" from Misrata, whose fighters make up "the largest block of Libya Dawn's forces".[190] The coalition was formed in 2014 as a reaction against General Khalifa Haftar failed coup and to defeat Zintan brigades controlling Tripoli International Airport whose aligned with him.

The Zawia tribe has been allied to Libya Dawn since August 2014,[191] although in June 2014 at least one Zawia army unit had appeared to side with General Haftar, and reports in December claimed Zawia forces were openly considering breaking away from Libya Dawn.[192] Zawia militia have been heavily fighting the Warshefana tribe. In the current conflict, the Warshefana have been strongly identified with the forces fighting against both Libya Dawn and Al Qaeda. Zawia has been involved in a long-standing tribal conflict with the neighbouring Warshefana tribe since 2011.[193] The motivations of the Zawia brigades participation in the war have been described as unrelated to religion and instead deriving foremost from tribal conflict with the Warshafana and secondarily as a result of opposition to the Zintani brigades and General Haftar.[194]

When the head of GNA Fayez Sarraj arrived in Tripoli, Libya Dawn has been disbanded as the interests of the militias forming it conflicted when some of them choose to support GNA others chose to stay loyal to GNC.

Libya Shield

The Libya Shield Force supports the Islamists. Its forces are divided geographically, into the Western Shield, Central Shield and Eastern Shield. Elements of the Libya Shield Force were identified by some observers as linked to Al-Qaeda as early as 2012.[165][166] The term "Libya Shield 1" is used to refer to the Islamist part of the Libya Shield Force in the east of Libya.[195]

In western Libya, the prominent Islamist forces are the Central Shield (of the Libya Shield Force), which consists especially of Misrata units and the Libya Revolutionaries Operations Room. Two smaller organizations operating in western Libya are Ignewa Al-Kikly and the "Lions of Monotheism".

Al-Qaeda leader Abd al-Muhsin Al-Libi, also known as Ibrahim Ali Abu Bakr or Ibrahim Tantoush[163] has been active in western Libya, capturing the special forces base called Camp 27 in April 2014 and losing it to anti-Islamist forces in August 2014.[162] The Islamist forces around Camp 27 have been described as both Al-Qaida[162] and as part of the Libya Shield Force.[164] The relationship between Al-Qaeda and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb is unclear, and their relationship with other Libyan Islamist groups is unclear. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb are also active in Fezzan, especially in border areas.

Libya western and central Libya Shield force fought alongside Libya Dawn and were disbanded with it in 2015. While the eastern Libya Shield forces merged later with other Islamist militias and formed Revolutionary Shura Council to fight Hafter LNA.

Revolutionary Shura Councils

In Benghazi, the Islamist armed groups have organized themselves into the Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries. These include:

The Shura Council of Benghazi has been strongly linked with ISIL as they fought together against Hafter in Battle of Benghazi. However, the Shura Council never pledged allegiance to ISIL.[187]

Meanwhile, in Derna the main Islamist coalition Shura Council of Mujahideen which was formed in 2014 is an al-Qaeda-affiliated group. The coalition has been in fight with ISIL in 2015 and drove them out from the city.[187]

Ajdabiya had its own Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries, which is the most ISIL linked among the three Shura councils. Its leader Muhammad al-Zawi and a number of the council pledging allegiance to ISIL played a major role in strengthening the Islamist group grip on Sirte.[187]

Benghazi Defense Brigades

Benghazi Defense Brigades was formed in June 2016 to defend Benghazi and the Shura Council from the Libyan National Army, the Benghazi Defence Brigades (BDB) included various Libya Dawn militias and was organized under the banner of the former Grand mufti Saddiq Al-Ghariyani.[196][197] Even though it pledged to support the GNA[197] and apparently working under Mahdi Al-Barghathi, the Defence Minister of the GNA.[198] The GNA never recognized the BDB with some members calling for it to be demarcated as a "terrorist organization".[199]

Amazigh militias

Even though the Amazigh militias mainly situated in Zuwara and Nafusa Mountains fought alongside Libya Dawn, they consider themselves pushed towards that because Zintan brigades and the rest of their enemies has been sided with HoR.[200] Still though, the Amazigh main motivations for fighting against Haftar is his Pan-Arabic ideas which is conflicting with their demands of recognition their language in the constitution as an official language.

While keeping their enmity towards Haftar, the Amazigh militias mostly became neutral later in the war especially since the formation of GNA.

Operation Dignity

The anti-Islamist Operation Dignity forces are built around Haftar's faction of the Libyan National Army, including land, sea and air forces along with supporting local militias.

LNA

The Libyan National Army, formally known as "Libyan Arab Armed Forces", was gradually formed by General Khalifa Haftar as he fought in what he named Operation Dignity. On 19 May 2014, a number of Libyan military officers announced their support for Gen. Haftar, including officers in an air force base in Tobruk, and others who have occupied a significant portion of the country's oil infrastructure, as well as members of an important militia group in Benghazi. Haftar then managed to gather allies from Bayda, 125 miles east of Benghazi.[201] A minority portion of the Libya Shield Force had been reported to not have joined the Islamist forces, and it is not clear if this means they had joined the LNA forces.[202]

Since then Haftar continued to strengthen his LNA by recruiting new soldiers along with the advancements he made on the ground. In 2017 Haftar said that his forces are now larger by "hundred times" and now they are about 60 thousand soldiers.[203]

Salafist militias

Salafists, called Madkhalis by their enemies, fought alongside Haftar LNA since the beginning against the Islamist militias, especially Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries and IS whom they considered Khawarij after a fatwa from Saudi Rabee al-Madkhali.[204]

Zintan brigades

Since the Battle of Tripoli Airport, armed groups associated with Zintan and the surrounding Nafusa region have become prominent. The Airport Security Battalion is recruited in large part from Zintan. The "Zintan Brigades" fall under the leadership of the Zintan Revolutionaries' Military Council.

Wershefana militias

Wershefana tribal and mainly Gaddafi loyalists armed groups, from the area immediately south and west of Tripoli, have been active in and among Haftar forces west of Libya.

On 5 August 2014, Warshefana forces captured Camp 27, a training base west of Tripoli.[164] Wershefana armed groups have also been involved in a tribal conflict with the neighbouring Zawia city since 2011.[193] Zawia has allied with Libya Dawn since August 2014,[191] although its commitment to Libya Dawn is reportedly wavering.[192]

After being accused of kidnapping, ransoming and other crimes, a GNA joint force made up mostly from Zintan brigades seized the Wershefana district.[205]

Kaniyat militia

Since the 2011 Libyan uprising against Muammar Gaddafi, the Kaniyat militiamen dominated and brutalized the civilians in Tarhuna to deepen their control over the strategic city. Formed by the Kani brothers, the militia committed atrocities that became known in 2017. The militia allied with the Government of National Accord (GNA) in 2016, which considered the Kaniyat important for their control over the 7th Brigade, gateway to Tripoli from south Libya. Human rights activists and the residents said the GNA and the UN provided political support to the militia and "chose not to see" the abuses and killings.[206]

In 2019, the Kaniyat militia aligned with the UAE-backed Khalifa Haftar and put their fighters under the general's 9th Brigade. Following that, the killings and disappearances in Tarhuna amplified. Over a decade until 2021, over 1,000 civilians were killed by the Kaniyat militia, where nearly 650 were killed in 14 months under Haftar. In 2020, the GNA forces successfully ousted the militia and the UAE-backed Haftar's forces and captured Tarhuna. Survivors reported of being tortured, electrocuted and beaten by the militia. Around 120 bodies were recovered from the mass graves, of which only 59 were identified.[206]

Ethnic tensions

In 2014, a former Gaddafi officer reported to the New York Times that the civil war was now an "ethnic struggle" between Arab tribes (like the Zintanis) against those of Turkish ancestry (like the Misuratis), as well as against Berbers and Circassians.[207]

Effects

Summarize

Perspective

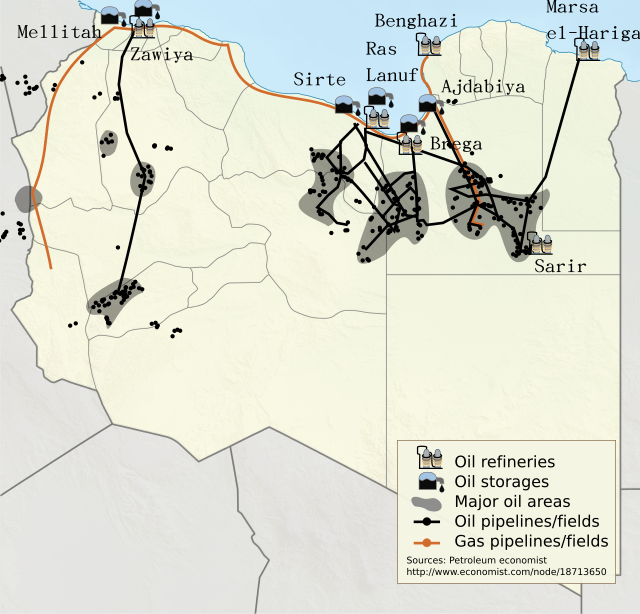

As of February 2015, damage and disorder from the war has been considerable.[208] There are frequent electric outages, little business activity, and a loss in revenues from oil by 90%.[208] Over 5,700 people died from the fighting by the end of 2016,[119] and some sources claim nearly a third of the country's population has fled to Tunisia as refugees.[208]

Since Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar had captured the ports of Libya's state-run oil company, the National Oil Corporation, in Es Sider and Ra's Lanuf, oil production has risen from 220,000 barrels a day to about 600,000 barrels per day.[209]

The war has prompted a considerable number of the country's sizeable foreign labour force to leave the country as extremist groups such as ISIL have targeted them; prior to the 2011, the Egyptian Ministry of Labour estimated that there were two million Egyptians working in the country yet since the escalation of attacks on Egyptian labourers the Egyptian Foreign Ministry estimates more than 800,000 Egyptians have left the country to return to Egypt.[210] Land mines remain a persistent threat in the country as numerous militias, especially ISIL, have made heavy use of land mines and other hidden explosives; the rapidly changing front lines has meant many of these devices remain in areas out of active combat zones; civilians remain the primary casualties inflicted by land mines with mines alone killing 145 people and wounding another 1,465 according to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).[211][212]

In a report, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) revealed that it had registered over 45,600 refugees and asylum seekers in Libya during 2019.[213] The World Food Programme reported that an estimated 435,000 people had been forcibly displaced from their homes during the conflict.[214]

On 22 October 2019, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) reported that children have been suffering from different sorts of malnutrition in the war-torn nations, including Libya.[215]

Executive Director of UNICEF said on 18 January 2020, that thousands of Libyan children were at risk of being killed due to the ongoing conflict in Libya. Since hostile clashes between the Libyan government and Haftar's LNA forces (backed by the UAE and Egypt) have broken out in Tripoli and western Libya, conditions of children and civilians have worsened.[216]

The blockade on Libya's major oil fields and production units by Haftar's forces has sown losses of over $255 million within the six-day period ending 23 January, according to the National Oil Corporation in Libya.[217] The NOC and ENI, which runs Mellitah Oil & Gas in Libya, have suffered a production loss of 155,000 oil barrels per day due to the blockade on production facilities imposed by Haftar's LNA. The entities claim losing revenue of around $9.4mn per day.[218]

Since the beginning of Libyan conflict, thousands of refugees forced to live in detention centres are suffering from mental health problems, especially women and children, who are struggling to confront the deaths of their family members in the war.[219]

On 7 February 2020, the UNHCR reported that the overall number of migrants intercepted by the Libyan coast guard in January surged 121% against the same period in 2019. The ongoing war has turned the country into a huge haven for migrants fleeing violence and poverty in Africa and the Middle East.[220]

On 6 April, an armed group invaded a control station in Shwerif, the Great Man-Made River project, stopped water from being pumped to Tripoli, and threatened the workers. The armed group's move was a way to pressure and force the release of the detained family members. On 10 April 2020, the United Nations humanitarian coordinator for Libya, Yacoub El Hillo condemned the water supply cutoff as "particularly reprehensible".[221]

On 21 April 2020, the UN took in to consideration the "dramatic increase" of shelling on densely populated areas of Tripoli, and claimed that continuation of war is worsening the humanitarian situation of Libya. The organisation also warned that such activities could possibly lead to war crimes.[222]

The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) in its first quarter report for 2020 on the civilian casualty in Libya cited that approximately 131 casualties have taken place between 1 January and 31 March 2020. The figures included 64 deaths and 67 injuries, all of which were a result of the ground fighting, bombing and targeted killing led by Khalifa Haftar's army, the LNA, backed by the United Arab Emirates.[223][224]

On 5 May 2020, The International Criminal Court's chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, raised concerns over the continuous spree of attacks by Haftar on Tripoli. The prosecutor said that actions endanger lives and warned of possible war crimes due to current affairs. "Of particular concern to my Office are the high numbers of civilian casualties, largely reported to be resulting from airstrikes and shelling operations," she expressed in a statement.[225]

On 10 November 2020, prominent Libyan activist, Hanane al-Barassi, was killed in Benghazi. The 46-year-old Barassi was an outspoken critic of humanitarian abuses committed in the eastern areas controlled by UAE-backed Khalifa Haftar's Libyan National Army (LNA). She was known for giving voice to female victims of violence through the videos she posted on social media.[226]

Timeline

Peace process

Summarize

Perspective

During the first half of 2015, the United Nations facilitated a series of negotiations seeking to bring together the rival governments and warring militias of Libya.[227] A meeting between the rival governments was held at Auberge de Castille in Valletta, Malta on 16 December 2015. On 17 December, delegates from the two governments signed a peace deal backed by the UN in Skhirat, Morocco, although there was opposition to this within both factions.[2][3] The Government of National Accord was formed as a result of this agreement, and its first meeting took place in Tunis on 2 January 2016.[228] On 17 December 2017, general Khalifa Haftar declared the Skhirat agreement void.[229]

A meeting called the Libyan National Conference was planned in Ghadames for organising elections and a peace process in Libya.[230] The conference was prepared over 18 months during 2018 and 2019 and was planned to take place 14–16 April 2019.[231] It was postponed in early April 2019 as a result of the military actions of the 2019 Western Libya offensive.[232]

In July 2019, Ghassan Salamé, the head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), proposed a three-point peace plan (a truce during Eid al-Adha, an international meeting of countries implicated in the conflict, and an internal Libyan conference similar to the Libyan National Conference).[233]

In September 2019, the Peace and Security Council (PSC) of the African Union (AU) discussed the need for the PSC to play a greater role in concluding the Libyan crisis, putting forward a proposal to appoint a joint AU-UN envoy to Libya.[234]

Turkish President RT Erdogan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin made a joint call for ceasefire, starting 12 January 2020, to end the proxy war in Libya.[235] The ceasefire is said to have been broken hours after its initiation. Both the warring parties – GNA supported by Turkey and LNA backed by Saudi, UAE, Egypt and Jordan – blamed each other for the violence that broke out in Tripoli.[236] Turkey's Foreign Minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said Khalifa Haftar, who is backed by foreign powers including the UAE, does not want peace and is seeking a military solution to the drawn-out war in the country.[237]

Haftar's forces launched attacks on Abu Gurain province, near the port city of Misurata, Libya's UN-recognized government claimed. The attacks were seen as a violation of cease-fire accord signed at the Berlin Conference.[238] On 12 February, the United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution demanding a "lasting cease-fire" in Libya. Drafted by Britain, it received 14 votes, while Russia abstained.[239] Around 19 February, the government withdrew from peace talks following rocket attacks on Tripoli.[240]

At the urging of the UN, both sides agreed to a new ceasefire in late March due to the novel coronavirus; however, the ceasefire quickly fell apart. On 24 March shells hit a prison in an area held by the GNA, drawing UN condemnation. The GNA launched a series of "counter-attacks" early on 25 March, in response to what the GNA called "the heaviest bombardments Tripoli has seen".[241] In June 2020, Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi brokered an agreement with parties aligned to the Libyan National Army, calling it the Cairo Declaration – However, this was quickly rejected.[242]

On 21 August 2020, Libya's rival authorities announced an immediate ceasefire. The Tripoli-based and internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) published a statement that also calls for elections in March 2021.[243][244]

The United Nations Security Council received a confidential report in September 2020, which provided details of the extensive violations of the international arms embargo on Libya, since the beginning of 2020. The UN identified eight countries breaching embargo. Besides, the United Arab Emirates and Russia were found to have sent five cargo aircraft filled with weapons to Libya on 19 January 2020, when the world leaders were signing a pledge to respect the arms embargo on Libya, at the Berlin conference. Four out of the five cargo airplanes belonged to the UAE.[245]

On 16 September 2020, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu told CNN Turk that Turkey and Russia have moved closer to an agreement on a ceasefire and political process in Libya during their latest meetings in Ankara. According to Reuters, Turkey and Russia were the main power brokers in the Libyan war, backing opposing sides. Russia supported the eastern-based forces of Khalifa Haftar, while Turkey backed Libya's internationally recognised Government of National Accord.[246]

In September 2020, the European Union issued sanctions against two people, who were indirectly or directly engaged in serious human rights abuses. While Benghazi-based Mahmoud al-Werfalli was engaged in violations like killings and executions, Moussa Diab was involved in human trafficking and the kidnapping, raping and killing of migrants and refugees. Three companies, Turkish maritime firm Avrasya Shipping, Jordan-based Med Wave Shipping and a Kazakhstan-based air freight company, Sigma Airlines, were also sanctioned for breaching the UN arms embargo by transferring military material to Libya.[247] Among these, Sigma Airlines was also found involved in the air-borne hard cash shipments for the Khalifa Haftar's government from the United Arab Emirates, Russia and the United Kingdom, among others. Sigma Airlines was also involved in a bank-note delivery made on 29 January 2019 for the LNA, using a commercial network operating through the UAE, Ukraine, Jordan and Belarus. In approximately $227 million bank note transfers, $91 million came from the UK, $27 million from Russia and $5 million from the UAE, which recorded highest number of transfers among 14 countries that were involved.[248][249]

On 23 October 2020, the 5+5 Joint Libyan Military Commission representing the LNA and the GNA reached a "permanent ceasefire agreement in all areas of Libya". The agreement, effective immediately, required that all foreign fighters leave Libya within three months while a joint police force would patrol disputed areas. The first commercial flight between Tripoli and Benghazi took place that same day.[143][144] The war concluded on 24 October 2020.[250]

UN-sponsored peace talks failed to establish an interim government by 16 November 2020, although both sides pledged to try again in a week.[251]

Talks by the Advisory Committee of the Libya Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF) in Geneva during 13–16 January 2021 produced a proposal for a procedure for selecting a unified executive authority. On 18 January, 72 of the LPDF members participated in a vote on the proposal. The proposal passed, attaining more than the 63% decision threshold, with 51 voters in favour, 19 against, 2 abstentions and 2 absences. The validated electoral procedure involves electoral colleges, support from the West, East and South of Libya, a 60% initial threshold, and a 50% plus one second-round threshold, for positions in the Presidency Council and for the prime ministership.[252][253]

On 19 February 2021, a confidential report by the United Nations revealed that the former CEO of Blackwater, Erik Prince breached the Libyan arms embargo by supporting and supplying weapons to Khalifa Haftar under an operation that cost $80 million. In 2019, Prince deployed foreign mercenaries to eastern Libya, who were armed with gunboats, attack aircraft, and cyberwarfare capabilities. While the report didn't conclude who funded the mercenary operation, analysts and Western officials asserted that it was most likely the UAE. The report noted that the mercenaries had offices, shell companies, and bank accounts in the Gulf nation.[254]

The FBI also opened an investigation into the failed mercenary plot of 2019. The agency was also looking into determining the role of Erik Prince in the attempted sale of aircraft and other materiel from Jordan to the UAE-backed Khalifa Haftar. Previous reports have highlighted that a Jordanian royal Feisal Ibn al-Hussein worked with Prince to organize the weapons transfer to Libya. However, the Jordanian government had aborted the sale.[255] Following which, Prince organized a meeting between his business associate Christiaan Durrant and a member of Donald Trump's National Security Council. During the meeting, Durrant explained Prince's Libyan campaign plan backing Haftar to the NSC official and asked for the US' support.[256] A UN report also revealed that three aircraft controlled or owned by Prince were transferred to a mercenary firm connected to him and located in the United Arab Emirates. However, Prince was not charged with a crime.[255]

Reactions

Summarize

Perspective

Domestic reactions

Khalifa Haftar and his supporters describe Operation Dignity as a "correction to the path of the revolution" and a "war on terrorism".[257][258][259] The elected parliament has declared that Haftar's enemies are "terrorists".[189] Opponents of Haftar and the House of Representatives' government in Tripoli claim he is attempting a coup. Omar al-Hasi, the internationally unrecognized Prime Minister of the Libya Dawn-backed Tripoli government, speaking of his allies' actions, has stated that: "This is a correction of the revolution." He has also contended: "Our revolution had fallen into a trap."[260] Dawn commanders claim to be fighting for a "revolutionary" cause rather than for religious or partisan objectives.[261] Islamist militia group Ansar al-Sharia (linked to the 2012 Benghazi attack) has denounced Haftar's campaign as a Western-backed "war on Islam"[262] and has declared the establishment of the "Islamic Emirate of Benghazi".

The National Oil Corporation (NOC) denounced calls to blockade oil fields prior to the Berlin Conference on 19 January 2020, calling it a criminal act. The entity warned to prosecute offenders to the highest degree under Libyan and international law.[263]

Dignitaries from Tripoli, Sahel and Mountain regions in Libya expressed discomposure at the UN envoy's briefing to Libya, Ghassan Salame at the Security Council, for equalizing the aggressors (Haftar's forces backed by UAE and Egypt) and the defender (GNA forces). They said Salame's statements made both the parties equal amid Haftar's offensive in Tripoli and the war crimes committed against civilians, including children.[264]

Foreign reactions, involvement, and evacuations

Neighboring countries

Algeria – Early in May 2014, the Algerian military said it was engaged in an operation aimed at tracking down militants who infiltrated the country's territory in Tamanrasset near the Libyan border, during which it announced that it managed to kill 10 "terrorists" and seized a large cache of weapons near the town of Janet consisting of automatic rifles, rocket-propelled grenades and ammunition boxes.[265] The Times reported on 30 May that Algerian forces were strongly present in Libya and it was claimed shortly after by an Algerian journalist from El Watan that a full regiment of 3,500 paratroopers logistically supported by 1,500 other men crossed into Libya and occupied a zone in the west of the country. They were later shown to be operating alongside French special forces in the region. However, all of these claims were later denied by the Algerian government through Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal who told the senate that "Algeria has always shown its willingness to assist [our] sister countries, but things are clear: the Algerian army will not undertake any operation outside Algerian territory".[266] On 16 May 2014, the Algerian government responded to a threat on its embassy in Libya by sending a team of special forces to Tripoli to escort its diplomatic staff in a military plane out of the country. "Due to a real and imminent threat targeting our diplomats the decision was taken in coordination with Libyan authorities to urgently close our embassy and consulate general temporarily in Tripoli," the Algerian Foreign Ministry said in a statement.[267] Three days later, the Algerian government shut down all of its border crossings with Libya and the army command raised its security alert status by tightening its presence along the border, especially on the Tinalkoum and Debdab border crossings. This also came as the state-owned energy firm, Sonatrach, evacuated all of its workers from Libya and halted production in the country.[268] In mid-August, Algeria opened its border for Egyptian refugees stranded in Libya and said it would grant them exceptional visas to facilitate their return to Egypt.[269]

Algeria – Early in May 2014, the Algerian military said it was engaged in an operation aimed at tracking down militants who infiltrated the country's territory in Tamanrasset near the Libyan border, during which it announced that it managed to kill 10 "terrorists" and seized a large cache of weapons near the town of Janet consisting of automatic rifles, rocket-propelled grenades and ammunition boxes.[265] The Times reported on 30 May that Algerian forces were strongly present in Libya and it was claimed shortly after by an Algerian journalist from El Watan that a full regiment of 3,500 paratroopers logistically supported by 1,500 other men crossed into Libya and occupied a zone in the west of the country. They were later shown to be operating alongside French special forces in the region. However, all of these claims were later denied by the Algerian government through Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal who told the senate that "Algeria has always shown its willingness to assist [our] sister countries, but things are clear: the Algerian army will not undertake any operation outside Algerian territory".[266] On 16 May 2014, the Algerian government responded to a threat on its embassy in Libya by sending a team of special forces to Tripoli to escort its diplomatic staff in a military plane out of the country. "Due to a real and imminent threat targeting our diplomats the decision was taken in coordination with Libyan authorities to urgently close our embassy and consulate general temporarily in Tripoli," the Algerian Foreign Ministry said in a statement.[267] Three days later, the Algerian government shut down all of its border crossings with Libya and the army command raised its security alert status by tightening its presence along the border, especially on the Tinalkoum and Debdab border crossings. This also came as the state-owned energy firm, Sonatrach, evacuated all of its workers from Libya and halted production in the country.[268] In mid-August, Algeria opened its border for Egyptian refugees stranded in Libya and said it would grant them exceptional visas to facilitate their return to Egypt.[269] Chad – In June 2020, Chadian President Idriss Déby announced his support to Khalifa Haftar's force in Libya, and had sent 1,500 to 2,000 troops to help Haftar, in wake of call from the United Arab Emirates to support Haftar's force against the strengthening Tripoli government and to end incursions by anti-Déby rebels.[270] Chadian oppositions have accused Khalifa Haftar of his attempt to assassinate Chadian opposition leaders.[271]

Chad – In June 2020, Chadian President Idriss Déby announced his support to Khalifa Haftar's force in Libya, and had sent 1,500 to 2,000 troops to help Haftar, in wake of call from the United Arab Emirates to support Haftar's force against the strengthening Tripoli government and to end incursions by anti-Déby rebels.[270] Chadian oppositions have accused Khalifa Haftar of his attempt to assassinate Chadian opposition leaders.[271] Egypt – Egyptian authorities have long expressed concern over the instability in eastern Libya spilling over into Egypt due to the rise of jihadist movements in the region, which the government believes to have developed into a safe transit for wanted Islamists following the 2013 coup d'état in Egypt that ousted Muslim Brotherhood-backed president Mohamed Morsi. There have been numerous attacks on Egypt's trade interests in Libya which were rampant prior to Haftar's offensive, especially with the kidnapping of truck drivers and sometimes workers were murdered.[272] Due to this, the military-backed government in Egypt had many reasons to support Haftar's rebellion and the Islamist February 17th Martyrs Brigade operating in Libya has accused the Egyptian government of supplying Haftar with weapons and ammunition, a claim denied by both Cairo and the rebel leader.[273] Furthermore, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who has become increasingly popular among many Libyans wishing for stability,[274] has called on the United States to intervene militarily in Libya during his presidential candidacy, warning that Libya was becoming a major security challenge and vowed not to allow the turmoil there to threaten Egypt's national security.[275] On 21 July 2014, the Egyptian Foreign Ministry urged its nationals residing in Libya to adopt measures of extreme caution as it was preparing to send consular staff in order to facilitate their return their country following an attack in Egypt's western desert region near the border with Libya that left 22 Egyptian border guards killed.[276] A week later, the ministry announced that it would double its diplomatic officials on the Libyan-Tunisian border and reiterated its call on Egyptian nationals to find shelter in safer places in Libya.[277] On 3 August, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia agreed to cooperate by establishing an airbridge between Cairo and Tunis that would facilitate the transfer of 2,000 to 2,500 Egyptians from Libya daily.[278] On 31 July 2014, two Egyptians were shot dead during a clash at the Libyan-Tunisian border where hundreds of Egyptians were staging a protest at the Ras Jdeir border crossing. As they tried to cross into Tunisia, Libyan authorities opened fire to disperse them.[279] A similar incident occurred once again on 15 August, when Libyan security forces shot dead an Egyptian who attempted to force his way through the border along with hundreds of stranded Egyptians and almost 1,200 Egyptians made it into Tunisia that day.[269] This came a few days after Egypt's Minister of Civil Aviation, Hossam Kamal, announced that the emergency airlift consisting of 46 flights aimed at evacuating the country's nationals from Libya came to a conclusion, adding that 11,500 Egyptians in total had returned from the war-torn country as of 9 August.[280] A week later, all Egyptians on the Libyan-Tunisian border were evacuated and the consulate's staff, who were reassigned to work at the border area, withdrew from Libya following the operation's success.[281] Meanwhile, an estimated 50,000 Egyptians (4,000 per day) arrived at the Salloum border crossing on the Libyan-Egyptian border as of early August.[282] In 2020, Egypt helped devise the 2020 Cairo Declaration, however, this was quickly rejected. On 21 June 2020, the President of Egypt, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi ordered his army to be prepared for any mission outside the nation, stating that his country has a legitimate right to intervene in neighboring Libya. Besides, he also warned the GNA forces to not cross the current frontline with Haftar's LNA.[283][284] An official statement issued by Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates on 21 June 2020, stated that the two Gulf nations extended full support to the Egypt's government regarding its intentions of military intervention in Libya. The UN-recognized GNA condemned Egypt, UAE, Russia and France for providing military support to Haftar's militias.[285]

Egypt – Egyptian authorities have long expressed concern over the instability in eastern Libya spilling over into Egypt due to the rise of jihadist movements in the region, which the government believes to have developed into a safe transit for wanted Islamists following the 2013 coup d'état in Egypt that ousted Muslim Brotherhood-backed president Mohamed Morsi. There have been numerous attacks on Egypt's trade interests in Libya which were rampant prior to Haftar's offensive, especially with the kidnapping of truck drivers and sometimes workers were murdered.[272] Due to this, the military-backed government in Egypt had many reasons to support Haftar's rebellion and the Islamist February 17th Martyrs Brigade operating in Libya has accused the Egyptian government of supplying Haftar with weapons and ammunition, a claim denied by both Cairo and the rebel leader.[273] Furthermore, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who has become increasingly popular among many Libyans wishing for stability,[274] has called on the United States to intervene militarily in Libya during his presidential candidacy, warning that Libya was becoming a major security challenge and vowed not to allow the turmoil there to threaten Egypt's national security.[275] On 21 July 2014, the Egyptian Foreign Ministry urged its nationals residing in Libya to adopt measures of extreme caution as it was preparing to send consular staff in order to facilitate their return their country following an attack in Egypt's western desert region near the border with Libya that left 22 Egyptian border guards killed.[276] A week later, the ministry announced that it would double its diplomatic officials on the Libyan-Tunisian border and reiterated its call on Egyptian nationals to find shelter in safer places in Libya.[277] On 3 August, Egypt, Libya and Tunisia agreed to cooperate by establishing an airbridge between Cairo and Tunis that would facilitate the transfer of 2,000 to 2,500 Egyptians from Libya daily.[278] On 31 July 2014, two Egyptians were shot dead during a clash at the Libyan-Tunisian border where hundreds of Egyptians were staging a protest at the Ras Jdeir border crossing. As they tried to cross into Tunisia, Libyan authorities opened fire to disperse them.[279] A similar incident occurred once again on 15 August, when Libyan security forces shot dead an Egyptian who attempted to force his way through the border along with hundreds of stranded Egyptians and almost 1,200 Egyptians made it into Tunisia that day.[269] This came a few days after Egypt's Minister of Civil Aviation, Hossam Kamal, announced that the emergency airlift consisting of 46 flights aimed at evacuating the country's nationals from Libya came to a conclusion, adding that 11,500 Egyptians in total had returned from the war-torn country as of 9 August.[280] A week later, all Egyptians on the Libyan-Tunisian border were evacuated and the consulate's staff, who were reassigned to work at the border area, withdrew from Libya following the operation's success.[281] Meanwhile, an estimated 50,000 Egyptians (4,000 per day) arrived at the Salloum border crossing on the Libyan-Egyptian border as of early August.[282] In 2020, Egypt helped devise the 2020 Cairo Declaration, however, this was quickly rejected. On 21 June 2020, the President of Egypt, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi ordered his army to be prepared for any mission outside the nation, stating that his country has a legitimate right to intervene in neighboring Libya. Besides, he also warned the GNA forces to not cross the current frontline with Haftar's LNA.[283][284] An official statement issued by Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates on 21 June 2020, stated that the two Gulf nations extended full support to the Egypt's government regarding its intentions of military intervention in Libya. The UN-recognized GNA condemned Egypt, UAE, Russia and France for providing military support to Haftar's militias.[285] Malta – Along with most of the international community, Malta continues to recognize the Government of National Accord as the legitimate government of Libya.[286] I Eastern Libyan government chargé d'affaires Hussin Musrati insisted that by doing so, Malta was "interfering in Libyan affairs".[287] Due to the conflict, there are currently two Libyan embassies in Malta. The General National Congress now controls the official Libyan Embassy in Balzan, while the Tobruk-based Eastern Libyan House of Representatives has opened a consulate in Ta' Xbiex. Each of the two embassies say that visas issued by the other entity are not valid.[288] Following the expansion of ISIL in Libya, particularly the fall of Nawfaliya, the Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and Leader of the Opposition Simon Busuttil called for the United Nations and European Union to intervene in Libya to prevent the country from becoming a failed state.[289][290] In 2020 Malta stated that its policy on Libya was in line with that of Turkey.[76]

Malta – Along with most of the international community, Malta continues to recognize the Government of National Accord as the legitimate government of Libya.[286] I Eastern Libyan government chargé d'affaires Hussin Musrati insisted that by doing so, Malta was "interfering in Libyan affairs".[287] Due to the conflict, there are currently two Libyan embassies in Malta. The General National Congress now controls the official Libyan Embassy in Balzan, while the Tobruk-based Eastern Libyan House of Representatives has opened a consulate in Ta' Xbiex. Each of the two embassies say that visas issued by the other entity are not valid.[288] Following the expansion of ISIL in Libya, particularly the fall of Nawfaliya, the Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and Leader of the Opposition Simon Busuttil called for the United Nations and European Union to intervene in Libya to prevent the country from becoming a failed state.[289][290] In 2020 Malta stated that its policy on Libya was in line with that of Turkey.[76] Sudan – At the early stage of the conflict, Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir, an Islamist himself, had sought to reach support to the Tripoli government, having supplied weaponry and aids to the rebels overthrowing Muammar Gaddafi.[291] However, after al-Bashir's realignment with Saudi Arabia in wake of Yemeni conflict, Sudan provided support to Haftar's force to gain support from Saudi Arabia. Sudan had sent 1,000 militia personnel to aid Haftar.[292] Nonetheless, in July 2017, General Khalifa Haftar of the Libyan National Army ordered the closing of the Sudanese consulate in the town of Kufra, and expelled 12 diplomats. The consul and 11 other consular staff were given 72 hours to leave the country. The reason given that the way it conducted its work was "damaging to Libyan national security." The Sudanese government protested and summoned Libyan chargé d'affaires in Khartoum, Ali Muftah Mahroug, in response, lingering the distrust between Haftar to the Sudanese. Sudan recognises the Government of National Accord in Tripoli as the government of Libya, not the House of Representatives that is backed by General Haftar. As of 2017 Sudan has not opened an embassy in Tripoli but maintains a consulate in the Libyan capital to provide service to Sudanese citizens.[293] In 2020, following the overthrown of Omar al-Bashir, Sudan has sought to investigate the role of the United Arab Emirates on bringing Sudanese mercenaries fighting in Libya and have arrested a number of them.[294][295]

Sudan – At the early stage of the conflict, Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir, an Islamist himself, had sought to reach support to the Tripoli government, having supplied weaponry and aids to the rebels overthrowing Muammar Gaddafi.[291] However, after al-Bashir's realignment with Saudi Arabia in wake of Yemeni conflict, Sudan provided support to Haftar's force to gain support from Saudi Arabia. Sudan had sent 1,000 militia personnel to aid Haftar.[292] Nonetheless, in July 2017, General Khalifa Haftar of the Libyan National Army ordered the closing of the Sudanese consulate in the town of Kufra, and expelled 12 diplomats. The consul and 11 other consular staff were given 72 hours to leave the country. The reason given that the way it conducted its work was "damaging to Libyan national security." The Sudanese government protested and summoned Libyan chargé d'affaires in Khartoum, Ali Muftah Mahroug, in response, lingering the distrust between Haftar to the Sudanese. Sudan recognises the Government of National Accord in Tripoli as the government of Libya, not the House of Representatives that is backed by General Haftar. As of 2017 Sudan has not opened an embassy in Tripoli but maintains a consulate in the Libyan capital to provide service to Sudanese citizens.[293] In 2020, following the overthrown of Omar al-Bashir, Sudan has sought to investigate the role of the United Arab Emirates on bringing Sudanese mercenaries fighting in Libya and have arrested a number of them.[294][295] Tunisia – Post-revolutionary Tunisia also had its share of instability due to the violence in Libya as it witnessed an unprecedented rise in radical Islamism with increased militant activity and weapons' smuggling through the border.[296] In response to the initial clashes in May, the Tunisian National Council for Security held an emergency meeting and decided to deploy 5,000 soldiers to the Libyan–Tunisian border in anticipation of potential consequences from the fighting.[297] On 30 July 2014, Tunisian Foreign Minister Mongi Hamdi said that the country cannot cope with the high number of refugees coming from Libya due to the renewed fighting. "Our country's economic situation is precarious, and we cannot cope with hundreds of thousands of refugees," Hamdi said in a statement. He also added that Tunisia will close its borders if necessary.[298] Tunisian Foreign Minister, Khemaies Jhinaoui, revived Tunisia's stance to stop the fighting in Libya and follow the UN-led political suit. He stressed on rejection of military solutions to the war.[299] In January 2020, Tunisia said that it is preparing to accommodate a new inflow of migrants escaping the war in Libya. The country has chosen the site of Fatnassia to receive Libyan refugees.[300]

Tunisia – Post-revolutionary Tunisia also had its share of instability due to the violence in Libya as it witnessed an unprecedented rise in radical Islamism with increased militant activity and weapons' smuggling through the border.[296] In response to the initial clashes in May, the Tunisian National Council for Security held an emergency meeting and decided to deploy 5,000 soldiers to the Libyan–Tunisian border in anticipation of potential consequences from the fighting.[297] On 30 July 2014, Tunisian Foreign Minister Mongi Hamdi said that the country cannot cope with the high number of refugees coming from Libya due to the renewed fighting. "Our country's economic situation is precarious, and we cannot cope with hundreds of thousands of refugees," Hamdi said in a statement. He also added that Tunisia will close its borders if necessary.[298] Tunisian Foreign Minister, Khemaies Jhinaoui, revived Tunisia's stance to stop the fighting in Libya and follow the UN-led political suit. He stressed on rejection of military solutions to the war.[299] In January 2020, Tunisia said that it is preparing to accommodate a new inflow of migrants escaping the war in Libya. The country has chosen the site of Fatnassia to receive Libyan refugees.[300]

Others

United Nations – On 27 August 2014, the UN Security Council unanimously approved resolution 2174 (2014), which called for an immediate ceasefire and an inclusive political dialogue.[301] The resolution also threatened to impose sanctions, such as asset freezes and travel bans, against the leaders and supporters of the various militias involved in the fighting, if the individuals threaten either the security of Libya or the political process.[302] The United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, expressed his fears of a "full civil war" in Libya, unless the international community finds a political solution for the country's conflict.[303] In 2019, the United Nations reported that Jordan, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates had systematically violated the Libyan arms embargo.[304] In February 2020, Libya's Ambassador to the UN, Taher Al-Sunni, emphasized on documenting attacks against civilians, medical personnel and field hospitals in Libya, during his meeting with the Director-General of the International Committee of the Red Cross.[305] Around 2 March 2020, Ghassan Salamé (the UN special envoy to Libya) resigned, citing the failure of powerful nations to meet their recent commitments.[306] In June 2020, UN secretary general, António Guterres condemned and expressed shock at discovering mass graves in a Libyan territory that was formerly captured by the forces of general Khalifa Haftar, backed by the governments of Egypt, Russia and the United Arab Emirates. Guterres commanded the UN-backed government to ensure identifying the victims, investigate into the cause of death and return the bodies to the respective family.[307] On 25 September 2020, UN diplomats revealed that Russia and China blocked the official release of a report by UN experts on Libya. The report accused the warring parties and their international backers, including Russia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, of violating the 2011 UN arms embargo on the war-torn country.[308] The UN identified the Sigma Airlines also known as Sigma Aviation and Air Sigma, a commercial cargo air company from Kazakhstan, as one of the commercial air cargo providers that have violated the arms embargo in Libya.[309] In March 2021, in a new report, UN accused United Arab Emirates, Russia, Egypt, Turkey and Qatar of extensive and blatant violations. The report included photos, diagrams and maps in order to support the accusations.[310][311] The UN report stated that Erik Prince attempted to deploy a Light Attack and Surveillance Aircraft (LASA) to Libya, disguised as a crop duster. The aircraft, LASA T-Bird, was owned by a UAE-based firm, L-6 FZE. Besides, it was modified with some deadly additions- “a 16-57mm Rocket Pod, a 32-57mm Rocket Pod and a gun pod fitted with twin 23mm cannon under its wings”.[312][313]

United Nations – On 27 August 2014, the UN Security Council unanimously approved resolution 2174 (2014), which called for an immediate ceasefire and an inclusive political dialogue.[301] The resolution also threatened to impose sanctions, such as asset freezes and travel bans, against the leaders and supporters of the various militias involved in the fighting, if the individuals threaten either the security of Libya or the political process.[302] The United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, expressed his fears of a "full civil war" in Libya, unless the international community finds a political solution for the country's conflict.[303] In 2019, the United Nations reported that Jordan, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates had systematically violated the Libyan arms embargo.[304] In February 2020, Libya's Ambassador to the UN, Taher Al-Sunni, emphasized on documenting attacks against civilians, medical personnel and field hospitals in Libya, during his meeting with the Director-General of the International Committee of the Red Cross.[305] Around 2 March 2020, Ghassan Salamé (the UN special envoy to Libya) resigned, citing the failure of powerful nations to meet their recent commitments.[306] In June 2020, UN secretary general, António Guterres condemned and expressed shock at discovering mass graves in a Libyan territory that was formerly captured by the forces of general Khalifa Haftar, backed by the governments of Egypt, Russia and the United Arab Emirates. Guterres commanded the UN-backed government to ensure identifying the victims, investigate into the cause of death and return the bodies to the respective family.[307] On 25 September 2020, UN diplomats revealed that Russia and China blocked the official release of a report by UN experts on Libya. The report accused the warring parties and their international backers, including Russia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, of violating the 2011 UN arms embargo on the war-torn country.[308] The UN identified the Sigma Airlines also known as Sigma Aviation and Air Sigma, a commercial cargo air company from Kazakhstan, as one of the commercial air cargo providers that have violated the arms embargo in Libya.[309] In March 2021, in a new report, UN accused United Arab Emirates, Russia, Egypt, Turkey and Qatar of extensive and blatant violations. The report included photos, diagrams and maps in order to support the accusations.[310][311] The UN report stated that Erik Prince attempted to deploy a Light Attack and Surveillance Aircraft (LASA) to Libya, disguised as a crop duster. The aircraft, LASA T-Bird, was owned by a UAE-based firm, L-6 FZE. Besides, it was modified with some deadly additions- “a 16-57mm Rocket Pod, a 32-57mm Rocket Pod and a gun pod fitted with twin 23mm cannon under its wings”.[312][313] France – On 30 July 2014, the French government temporarily closed its embassy in Tripoli, while 40 French, including the ambassador, and 7 British nationals were evacuated on a French warship bound for the port of Toulon in southern France. "We have taken all necessary measures to allow those French nationals who so wish to leave the country temporarily," the foreign ministry said.[314][315] In 2016, a helicopter carrying three French special forces soldiers was shot down south of Benghazi during what President François Hollande called "dangerous intelligence operations."[316][317] In December 2019, French government canceled the delivery of boats to Libya following a lawsuit filed by NGOs opposing the move. The NGOs cited the French donation as a violation of European embargo on Libya for providing military equipment and arms to countries involved in war crimes.[318]

France – On 30 July 2014, the French government temporarily closed its embassy in Tripoli, while 40 French, including the ambassador, and 7 British nationals were evacuated on a French warship bound for the port of Toulon in southern France. "We have taken all necessary measures to allow those French nationals who so wish to leave the country temporarily," the foreign ministry said.[314][315] In 2016, a helicopter carrying three French special forces soldiers was shot down south of Benghazi during what President François Hollande called "dangerous intelligence operations."[316][317] In December 2019, French government canceled the delivery of boats to Libya following a lawsuit filed by NGOs opposing the move. The NGOs cited the French donation as a violation of European embargo on Libya for providing military equipment and arms to countries involved in war crimes.[318] India – Ministry of External Affairs spokesman, Syed Akbaruddin, said that India's diplomatic mission in Libya has been in touch with the 4,500 Indian nationals, through several coordinators. "The mission is facilitating return of Indian nationals and working with the Libyan authorities to obtain necessary exit permissions for Indian nationals wanting to return," he said.[319]

India – Ministry of External Affairs spokesman, Syed Akbaruddin, said that India's diplomatic mission in Libya has been in touch with the 4,500 Indian nationals, through several coordinators. "The mission is facilitating return of Indian nationals and working with the Libyan authorities to obtain necessary exit permissions for Indian nationals wanting to return," he said.[319] Iran – Iran has facilitated a very difficult role in this conflict. Unlike many countries in the Middle East that Iran has interests, Iran has very little to none of interest in Libya, but Iran has desired to expand its Islamic Revolution to Africa.[320] However, Saudi Arabia's support for Haftar has complicated Iran's desire, as Iran has also been accused of supporting Haftar's force, even when Tehran has refrained from siding with Haftar.[321] On the other hand, Iran also provides political support to Turkey's military intervention to Libya.[322]

Iran – Iran has facilitated a very difficult role in this conflict. Unlike many countries in the Middle East that Iran has interests, Iran has very little to none of interest in Libya, but Iran has desired to expand its Islamic Revolution to Africa.[320] However, Saudi Arabia's support for Haftar has complicated Iran's desire, as Iran has also been accused of supporting Haftar's force, even when Tehran has refrained from siding with Haftar.[321] On the other hand, Iran also provides political support to Turkey's military intervention to Libya.[322] Israel – Israel and Libya do not have any official relations. However, during the time in exile, Khalifa Haftar had developed a close and secret tie with the United States, thus extended to Israel, and the secret tie resulted in Israel quietly backing Khalifa Haftar on his quest to conquer all of Libya.[323] Israeli advisors are alleged to have trained Haftar's force to prepare for war against the Islamist-backed government in Tripoli.[324] Israeli weapons are also seen in Haftar's forces, mostly throughout Emirati mediation.[325] The Mossad developed a strong relationship with Haftar and also assists his forces in the conflict.[326]

Israel – Israel and Libya do not have any official relations. However, during the time in exile, Khalifa Haftar had developed a close and secret tie with the United States, thus extended to Israel, and the secret tie resulted in Israel quietly backing Khalifa Haftar on his quest to conquer all of Libya.[323] Israeli advisors are alleged to have trained Haftar's force to prepare for war against the Islamist-backed government in Tripoli.[324] Israeli weapons are also seen in Haftar's forces, mostly throughout Emirati mediation.[325] The Mossad developed a strong relationship with Haftar and also assists his forces in the conflict.[326] Italy – The Italian embassy has remained open during the civil war[327] and the government has always pushed for the success of UN-hosted talks among Libya's political parties in Geneva. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said "If there's no success, Italy is ready to play a leading role, above all a diplomatic role, and then, always under the aegis of the UN, one of peacekeeping inside Libya", adding that "Libya can't be left in the condition it is now."[328] In 2015, four Italian workers were kidnapped by Islamic State militants near Sabratha. Two of them were killed in a raid by security forces the following year while the other two were rescued.[329] Between February 2015 and December 2016, however, Italy was forced to close its embassy and every Italian citizen in Libya was advised to leave. The embassy reopened on 9 January 2017.

Italy – The Italian embassy has remained open during the civil war[327] and the government has always pushed for the success of UN-hosted talks among Libya's political parties in Geneva. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said "If there's no success, Italy is ready to play a leading role, above all a diplomatic role, and then, always under the aegis of the UN, one of peacekeeping inside Libya", adding that "Libya can't be left in the condition it is now."[328] In 2015, four Italian workers were kidnapped by Islamic State militants near Sabratha. Two of them were killed in a raid by security forces the following year while the other two were rescued.[329] Between February 2015 and December 2016, however, Italy was forced to close its embassy and every Italian citizen in Libya was advised to leave. The embassy reopened on 9 January 2017. Morocco – Morocco turned down an offer by the United Arab Emirates in 2020 to provide support for Khalifa Haftar.[330] Instead, Morocco expressed its hope to mediate for the end of the conflict.[331]

Morocco – Morocco turned down an offer by the United Arab Emirates in 2020 to provide support for Khalifa Haftar.[330] Instead, Morocco expressed its hope to mediate for the end of the conflict.[331]

Russia – In February 2015, discussions on supporting the Libyan parliament by supplying them with weapons reportedly took place in Cairo when President of Russia Vladimir Putin arrived for talks with the government of Egypt, during which the Russian delegates also spoke with a Libyan delegation. Colonel Ahmed al-Mismari, the spokesperson for the Libyan Army's chief of staff, also stated that "Arming the Libyan army was a point of discussion between the Egyptian and Russian presidents in Cairo."[332] The deputy foreign minister of Russia, Mikhail Bogdanov, has stated that Russia will supply the government of Libya with weapons if UN sanctions against Libya are lifted.[333] In April 2015, Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thani visited Moscow and announced that Russia and Libya will strengthen their relations, especially economic relations.[334] He also met with Sergei Lavrov, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, and said that he requested Russia's assistance in fixing the country's government institutions and military strength.[335] The prime minister also met with Nikolai Patrushev, the Russian president's security adviser, and talked about the need to restore stability in Libya as well as the influence of terrorist groups in the country. Patrushev stated that a "priority for regional politics is the protection of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Libya."[336] As of 2 October 2019, between 10 and 35 Russian mercenaries had reportedly been killed in an airstrike in Libya while fighting for Khalifa Haftar's forces as per Latvian newslet Meduza.[337] In a joint press conference with the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed the involvement of Russian mercenaries in Tripoli's ongoing conflict. He also said they are not affiliated to Moscow and are not funded by the government. These fighters were transferred to Libya from the de-escalation zone in Syria's Idlib.[338]