Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

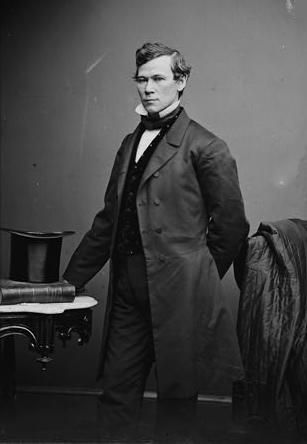

John F. Potter

American politician From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

John Fox Potter nicknamed "Bowie Knife Potter" (May 11, 1817 – May 18, 1899) was a nineteenth-century politician, lawyer and judge from Wisconsin who served in the Wisconsin State Assembly and the U.S. House of Representatives.[1][2]

Remove ads

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Admitted to the Wisconsin bar in 1837, Potter began his legal practice in East Troy. He served as a judge in Walworth County from 1842 to 1846.

A Whig, Potter was elected a member of the Wisconsin State Assembly, and served a term (1856–1857). He was a delegate to the 1852 Whig National Convention and 1856 Whig National Convention. With the demise of the Whig party, Potter became a Republican and became a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1860 and 1864.

Member of Congress

Wisconsin voters elected Potter to the United States House of Representatives in 1856 and he won re-election twice. Thus, Potter served in the 35th through the 37th Congresses (1857 to 1863). Potter received his nickname in 1860, as a result of an aborted duel with Virginia Congressman Roger A. Pryor after Illinois Congressman (and abolitionist) Owen Lovejoy's remarks concerning the 1837 murder of his brother Elijah Lovejoy. Pryor had edited Potter's follow-up remarks to eliminate a mention of the Republican Party, to which Potter had objected, then Pryor challenged Potter to a duel, but his seconds objected when Potter chose bowie knives as the prospective weapon, decrying his selection of weapon as "vulgar, barbarous, and inhuman."[3] The incident received considerable press, and Potter's friends afterward often accompanied him when on Washington's streets, lest he be accosted again to test his mettle.[4] Potter served as chairman of the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions from 1859 to 1861 and of the Committee on Public Lands from 1861 to 1863. In this latter role, his committee handled the Homestead Act of 1862. He was considered one of the "Radical Republicans" due to his support for African-American civil rights and the belief that not only should slavery not be allowed to expand, but that it should be banned in states where it currently existed.[5]

As relations with the southern states deteriorated and the Civil War eventually began in earnest, Potter was appointed to serve as the head of the House's "Committee on Loyalty of Federal employees", which sought to root out Confederate sympathizers in the government. His efforts and intrusiveness were not always appreciated; Secretary of War Simon Cameron in particular was annoyed by Potter's interference and repeatedly ignored his demands that Cameron dismiss at least fifty War Department staffers suspected of Confederate sympathies. Although frustrated by Cameron's recalcitrance, Potter did not actually have the authority to compel Cameron to follow his directives; only the President held that power and Lincoln's attentions were needed elsewhere.

The tumultuous relationship between Potter and the War Department was alleviated when Cameron was replaced by Edwin Stanton on January 20, 1862. Stanton met with Potter on his first day as war secretary, and on the same day, dismissed four persons whom Potter deemed unsavory. This was well short of the fifty people Potter wanted gone from the department, but he was nonetheless pleased with Stanton's initiative.

In 1861, Potter was one of the participants in the Peace Conference of 1861, which failed to avert the American Civil War. He was defeated in his race for reelection in 1862 by fellow Maine-born lawyer James S. Brown, a Democrat who had been Milwaukee prosecutor and mayor, and who would be defeated the following year by a Republican general. During the campaign, his son Alfred C. Potter had enlisted in the 28th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment in August 1862 as a sergeant, but would be mustered out the following April, and began receiving a pension in 1896.[6]

Remove ads

Later career

After Potter's congressional term ended in early 1863, he declined appointment as governor of Dakota Territory, and his wife died in May 1863 in Washington, D.C., leaving Potter a widower with a ten year old son. The Lincoln administration then appointed Potter as Consul General of the United States in the British-controlled Province of Canada from 1863 to 1866. Thus Potter resided in what was then the Canadian capital of Montreal, Lower Canada.

In 1866, Potter returned to East Troy, Wisconsin, where he resumed his legal practice.

Remove ads

Death and legacy

Potter died at his home on May 18, 1899. The Wisconsin Historical Society received his knife.[7]

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads