Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Since the Partition of British India in 1947 and subsequent creation of the dominions of India and Pakistan, the two countries have been involved in a number of wars, conflicts, and military standoffs. A long-running dispute over Kashmir and cross-border terrorism have been the predominant cause of conflict between the two states, with the exception of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, which occurred as a direct result of hostilities stemming from the Bangladesh Liberation War in erstwhile East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

| Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kashmir dispute and the Cold War | |||||||

Location of India (orange) and Pakistan (green) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| India | Pakistan | ||||||

Background

The Partition of India came in 1947 with the sudden grant of independence.[1] It was the intention of those who wished for a Muslim state to have a clean partition between independent and equal "Pakistan" and "Hindustan" once independence came.[2]

Nearly one third of the Muslim population of India remained in the new India.[3][4][5]

Inter-communal violence between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims resulted in between 200,000 and 2 million casualties leaving 14 million people displaced.[1][6][a][7]

Princely states in India were provided with an Instrument of Accession to accede to either India or Pakistan.[8]

Wars

Summarize

Perspective

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

The war, also called the First Kashmir War, started in October 1947 when Pakistan feared that the Maharaja of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu would accede to India. Following partition, princely states were left to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest of the princely states, had a majority Muslim population and significant fraction of Hindu population, all ruled by the Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh. Tribal Islamic forces with support from the army of Pakistan attacked and occupied parts of the princely state forcing the Maharaja to sign the Instrument of Accession of the princely state to the Dominion of India to receive Indian military aid. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on 22 April 1948. The fronts solidified gradually along what came to be known as the Line of Control. A formal cease-fire was declared at 23:59 on the night of 1 January 1949.[9]: 379 India gained control of about two-thirds of the state (Kashmir Valley, Jammu and Ladakh) whereas Pakistan gained roughly a third of Kashmir (Azad Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan). The Pakistan controlled areas are collectively referred to as Pakistan administered Kashmir.[10][11][12][13]

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

This war started following Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar, which was designed to infiltrate forces into Jammu and Kashmir to precipitate an insurgency against rule by India. India retaliated by launching a full-scale military attack on West Pakistan. The seventeen-day war caused thousands of casualties on both sides and witnessed the largest engagement of armored vehicles and the largest tank battle since World War II.[14][15] The hostilities between the two countries ended after a ceasefire was declared following diplomatic intervention by the Soviet Union and USA and the subsequent issuance of the Tashkent Declaration.[16] India had the upper hand over Pakistan when the ceasefire was declared.[17][18][19][20]

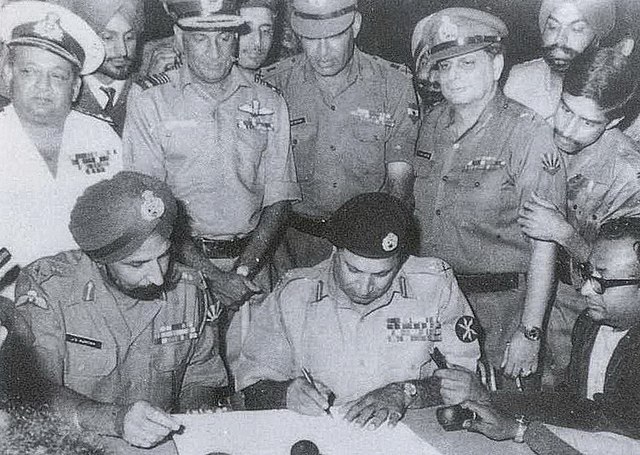

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

This war was unique in the way that it did not involve the issue of Kashmir, but was rather precipitated by the crisis created by the political battle brewing in erstwhile East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) between Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Leader of East Pakistan, and Yahya Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, leaders of West Pakistan. This would culminate in the declaration of Independence of Bangladesh from the state system of Pakistan. Following Operation Searchlight and the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities, about 10 million Bengalis in East Pakistan took refuge in neighbouring India.[22] India intervened in the ongoing Bangladesh liberation movement.[23][24] After a large scale pre-emptive strike by Pakistan, full-scale hostilities between the two countries commenced.

Pakistan attacked at several places along India's western border with Pakistan, but the Indian Army successfully held their positions. The Indian Army quickly responded to the Pakistan Army's movements in the west and made some initial gains, including capturing around 15,010 square kilometres (5,795 square miles)[25][26][27] of Pakistani territory (land gained by India in Pakistani Kashmir, Pakistani Punjab and Sindh sectors but gifted it back to Pakistan in the Simla Agreement of 1972, as a gesture of goodwill). Within two weeks of intense fighting, Pakistani forces in East Pakistan surrendered to the joint command of Indian and Bangladeshi forces following which the People's Republic of Bangladesh was created.[28] The war resulted in the surrender of more than 90,000 Pakistani Army troops.[29] In the words of one Pakistani author, "Pakistan lost half its navy, a quarter of its air force and a third of its army".[30]

Indo-Pakistani War of 1999

Commonly known as the Kargil War, this conflict between the two countries was mostly limited. During early 1999, Pakistani troops infiltrated across the Line of Control (LoC) and occupied Indian territory mostly in the Kargil district. India responded by launching a major military and diplomatic offensive to drive out the Pakistani infiltrators.[31] Two months into the conflict, Indian troops had slowly retaken most of the ridges that were encroached by the infiltrators.[32][33] According to official count, an estimated 75%–80% of the intruded area and nearly all high ground was back under Indian control.[34] Fearing large-scale escalation in military conflict, the international community, led by the United States, increased diplomatic pressure on Pakistan to withdraw forces from remaining Indian territory.[31][35] Faced with the possibility of international isolation, the already fragile Pakistani economy was weakened further.[36][37] The morale of Pakistani forces after the withdrawal declined as many units of the Northern Light Infantry suffered heavy casualties.[38][39] The government refused to accept the dead bodies of many officers,[40][41] an issue that provoked outrage and protests in the Northern Areas.[42][43] Pakistan initially did not acknowledge many of its casualties, but Nawaz Sharif later said that over 4,000 Pakistani troops were killed in the operation and that Pakistan had lost the conflict.[44][45] By the end of July 1999, organized hostilities in the Kargil district had ceased.[35] The war was a major military defeat for the Pakistani Army.[46][47]

Other armed engagements

Summarize

Perspective

Apart from the aforementioned wars, there have been skirmishes between the two nations from time to time. Some have bordered on all-out war, while others were limited in scope. The countries were expected to fight each other in 1955 after warlike posturing on both sides, but full-scale war did not break out.[16]

Siachen conflict

In 1984, India launched Operation Meghdoot capturing all of the Siachen Glacier. Further clashes erupted in the glacial area in 1985, 1987 and 1995 as Pakistan sought, without success, to oust India from its stronghold.[16][48]

Standing armed conflicts

As proxies

- Insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir (1989–present): An insurgency in Kashmir has been a cause for heightened tensions. India has also accused Pakistan-backed militant groups of executing several terrorist attacks across India.

- Insurgency in Balochistan (1948–present): An insurgency in Balochistan province of Pakistan has also caused tensions recently. Pakistan has accused India of causing the insurgency with the help of ousted Baloch leaders, militant groups and terrorist organizations like the Balochistan Liberation Army. According to Pakistani officials these militants are trained in neighboring Afghanistan. In 2016, Pakistan alleged that an Indian spy Kulbhushan Jadhav was arrested by Pakistani forces during a counter-intelligence operation in Balochistan.[49][50]

- Afghan conflict (1978–present): India and Pakistan had long been supporting opposing sides during the wars of Afghanistan,[51] including during the Soviet–Afghan War and the civil wars from 1989 to 2001.[52] In 2006, Pakistan has been accused by India for its involvement in terrorism in Afghanistan.[53] In 2020, Pakistan accused India of trying to derail peace negotiations to end the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021).[54]

Past skirmishes and standoffs

- 1958 East Pakistan-India border clashes: were armed skirmishes between East Pakistan and India in August 1958. The clashes took place between troops of the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) and the Indian Army in the village of Lakshmipur, located in Sylhet District.[citation needed]

- Operation Desert Hawk: A military operation executed by the Pakistan Armed Forces in the then disputed Rann of Kutch region.

- Operation Brasstacks: The largest of its kind in South Asia, it was conducted by India between November 1986 and March 1987. Pakistani mobilisation in response raised tensions and fears that it could lead to another war between the two neighbours.[16]: 129 [55]

- 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff: The terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament on 13 December 2001, which India blamed on the Pakistan-based terrorist organisations, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, prompted the 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff and brought both sides close to war.[56]

- 2008 Indo-Pakistani standoff: a stand-off between the two nations following the 2008 Mumbai attacks which was defused by diplomatic efforts. Following ten coordinated shooting and bombing attacks across Mumbai, India's largest city, tensions heightened between the two countries since India claimed interrogation results alleging[57][58] Pakistan's ISI supporting the attackers while Pakistan denied any official Pakistani involvement in the attacks.[59][60][61] Pakistan placed its air force on alert and moved troops to the Indian border, voicing concerns about proactive movements of the Indian Army[62] and the Indian government's possible plans to launch attacks on Pakistani soil.[63] The tension defused in a short time and Pakistan moved its troops away from the border.

- 2016–2018 India–Pakistan border skirmishes: On 29 September 2016, border skirmishes between India and Pakistan began following reported "surgical strikes" by India against militant launch pads across the Line of Control in Pakistani-administered Kashmir "killing a large number of terrorists".[64] Pakistan rejected that a strike took place,[65] stating that Indian troops had not crossed the Line of Control but had only skirmished with Pakistani troops at the border, resulting in the deaths of two Pakistani soldiers and the wounding of nine.[66][67] Pakistan rejected India's reports of any other casualties.[68] Pakistani sources reported that at least eight Indian soldiers were killed in the exchange, and one was captured.[69][70] India confirmed that one of its soldiers was in Pakistani custody, but denied that it was linked to the incident or that any of its soldiers had been killed.[71] The Indian operation was said to be in retaliation for a militant attack on the Indian army at Uri on 18 September in the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir that left 19 soldiers dead.[72][73] In the succeeding days and months, India and Pakistan continued to exchange fire along the border in Kashmir, resulting in dozens of military and civilian casualties on both sides.

- 2019 India–Pakistan border skirmishes: On 14 February 2019, a suicide attack on a convoy of India's CRPF resulted in the death of at least 40 troops. Responsibility for the attack was claimed by the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM).[74] 12 days later in February 2019, Indian jets crossed the international border to conduct air strikes on an alleged JeM camp in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan.[75][76] India claimed that it killed a very large number of militants belonging to JeM.[77] Pakistan rejected to have suffered any losses.[78] According to the sources and satellite imagery analysis, Indian air force appears to caused minimal damage to the buildings concerned,[79][80][81][82] however, Pakistan had to close the site for one and a half month or 43 days before opened to media.[83][84][85] The incidents escalated the tension between India and Pakistan. The following day, Indian and Pakistani air forces got locked on in an aerial engagement. Pakistan claimed to have shot down two Indian aircraft and capturing one pilot Abhinandan Varthaman. Pakistan military officials claimed that the wreckage of one Indian aircraft fell in Pakistan administered Kashmir while the other one fell in Indian administered Kashmir rumored to be a Sukhoi Su-30MKI. Meanwhile, Indian version was about loss a MiG-21 while shooting down a Pakistani F-16.[86][87] The IAF also displayed remnants of an AIM-120 AMRAAM missile that they claimed could only be fired by F-16's air planes. The missiles were said to have fired against and jammed by Su-30 by IAF.[88] Pakistan rejected the Indian claim of an F-16 shot down. It initially released three or later on displayed all four air to air missiles of MiG-21 Bison with all missile seeker heads recovered intact from the wreckage however with mid-body of one of R-73 destroyed and claimed that non-of missiles were ever fired.[89] Following the threats of a full-scale war,[90] Abhinandan was released within two days. The Pentagon correspondent of Foreign Policy magazine, in a report claimed that Pakistan invited the United States to physically count its F-16 planes after the incident. Two senior U.S. defense officials told Foreign Policy that U.S. personnel recently counted Pakistan's F-16s and found none missing.[91] A Pentagon spokesman said they were not aware of any count being conducted,[92] but the Pentagon did not put out any official statement on the matter. However, there have been no leaks countering the Foreign Policy report.[93] India released the electronic footage of aerial engagement to re-assert its claims.[94][95] Pakistani officials rejected radar images released by India.[96] Stand off followed with intermittent firings across the LoC. Months later on 8 October, India on its Air Force Day, flew the same Su-30MKI "Avenger 1" aircraft in a flypast that Pakistan had claimed it had shot down during the air battle on 27 February.[97]

- 2020–2021 India–Pakistan border skirmishes: The standoff intensified when a major exchange of gunfire and shelling erupted between Indian and Pakistani troops in November 2020 along the Line of Control which left at least 22 dead, including 11 civilians.[98] Pakistan's foreign ministry said India had violated the ceasefire at least 2,729 times in 2020 which killed 21 Pakistani civilians and seriously injured 206 others.[99] In February 2021, India and Pakistan released a joint statement, stating that after discussions over established hotlines, the two sides agreed to "strict observance" of all peace and ceasefire agreements with effect from midnight of 25 February 2021. Both sides agreed existing forms of hotline contact and border flag meetings would be utilized to resolve any future misunderstanding.[100][101][102]

Incidents

- 1999 Pakistani Atlantic shootdown: Pakistan Navy's Naval Air Arm's, Atlantic maritime patrol plane, carrying 16 people on board, was shot down by the Indian Air Force for alleged violation of airspace. The episode took place in the Rann of Kutch on 10 August 1999, just a month after the Kargil War, creating a tense atmosphere between India and Pakistan. Foreign diplomats noted that the plane fell inside Pakistani territory, although it may have crossed the border. However, they also believe that India's reaction was unjustified.[103] Pakistan later lodged a compensation claim at the International Court of Justice, accusing India for the incident, but the Court dismissed the case in a split decision ruling the Court did not have jurisdiction.[104]

- The 2011 India–Pakistan border shooting incident took place between 30 August and 1 September 2011 across the Line of Control in Kupwara district/Neelam Valley, resulting in five Indian soldiers[105] and three Pakistani soldiers being killed. Both countries gave different accounts of the incident, each accusing the other of initiating the hostilities.[106][107]

- 2013 India–Pakistan border incident in the Mendhar sector of Jammu and Kashmir, due to the beheading of an Indian soldier. A total of 22 soldiers (12 Indian and 10 Pakistani) died.[108]

- 2014–2015 India–Pakistan border skirmishes: Started in Arnia sector of Jammu and Kashmir due to killing of 1 soldier of Border Security Force and injured 3 soldiers and 4 civilians by Pakistan Rangers.[109]

Nuclear weapons

Summarize

Perspective

The nuclear conflict between both countries is of passive strategic nature with nuclear doctrine of Pakistan stating a first strike policy, although the strike would only be initiated if and only if, the Pakistan Armed Forces are unable to halt an invasion (as for example in 1971 war) or a nuclear strike is launched against Pakistan,[citation needed] whereas India has a declared policy of no first use. According to a peer-reviewed study published in the journal Nature Food in August 2022, a nuclear war between India and Pakistan could kill more than 2 billion indirectly by starvation during a nuclear winter.[110][111]

- Pokhran-I (Smiling Buddha): On 18 May 1974 India detonated an 8-kiloton nuclear device at Pokhran Test Range,[112] becoming the first nation to become nuclear capable outside the five permanent members of United Nations Security Council as well as dragging Pakistan along with it into a nuclear arms race. Pakistani prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had promised in 1965 that "if India builds the bomb, we will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own", and India's Pokhran-I test spurred the Pakistani nuclear weapons program to greater efforts.[113] The Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) Chairman Munir Ahmed Khan said that the test would force Pakistan to test its own nuclear bomb.[114]

- Kirana-I: In the 1980s a series of 24 different cold tests were conducted by PAEC, led by chairman Munir Ahmad Khan under extreme secrecy.[115] The tunnels at Kirana Hills, Sargodha, are reported to have been bored after the Chagai nuclear test sites, it is widely believed that the tunnels were constructed sometime between 1979 and 1983. As in Chagai, the tunnels at Kirana Hills had been bored and then sealed and this task was also undertaken by PAEC's DTD.[115] Later due to excessive US intelligence and satellite focus on the Kirana Hills site, it was abandoned and nuclear weapons testing was shifted to the Kala Chitta Range.[116]

- Pokhran-II (Operation Shakti): On 11 May 1998 India detonated another five nuclear devices at Pokhran Test Range. With jubilation and large scale approval from the Indian society came International sanctions as a reaction to this test, the most vehement reaction of all coming from Pakistan. Great ire was raised in Pakistan, which issued a stern statement claiming that India was instigating a nuclear arms race in the region. Pakistan vowed to match India's nuclear capability with statements like: "We are in a headlong arms race on the subcontinent".[117][118]

- Chagai-I: (Youm-e-Takbir) Within half a month of Pokhran-II, on 28 May 1998 Pakistan detonated five nuclear devices to reciprocate India in the nuclear arms race. The Pakistani public, like the Indian, reacted with a celebration and a heightened sense of nationalism for responding to India in kind and becoming the only Muslim nuclear power. The day was later given the title Youm-e-Takbir to further proclaim such.[119][120][121][122]

- Chagai-II: Two days later, on 30 May 1998, Pakistan detonated a sixth nuclear device completing its own series of underground tests with this being the last the two nations have carried out to date.[120][123]

Annual celebrations

The nations of South Asia observe national and armed forces-specific days which originate from conflicts between India and Pakistan as follows:

- 28 May (since 1998) as Youm-e-Takbir (The day of Greatness) in Pakistan.[124][125]

- 26 July (since 1999) as Kargil Vijay Diwas (Kargil Victory Day) in India.

- 6 September (since 1965) as Defence Day (Youm-e-Difa) in Pakistan.[126]

- 7 September (since 1965) as Air Force Day (Youm-e-Fizaya) in Pakistan.[126]

- 8 September (since 1965) as Victory Day/Navy Day (Youm-e-Bahr'ya) in Pakistan.

- 4 December (since 1971) as Navy Day in India.

- 16 December (since 1971) as Vijay Diwas (Victory Day) in India.

- 16 December (since 1971) as Bijoy Dibosh (Victory Day) in Bangladesh.

Involvement of other nations

- The USSR remained neutral during the 1965 war[127] and played a pivotal role in negotiating the peace agreement between India and Pakistan.[128]

- The Soviet Union provided diplomatic and military assistance to India during the 1971 war. In response to the US and UK's deployment of the aircraft carriers USS Enterprise and HMS Eagle, Moscow sent nuclear submarines and warships with anti-ship missiles in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, respectively.[129][130][131]

- The US had not given any military aid to Pakistan in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.[132]

- The United States provided diplomatic and military support to Pakistan during the 1971 war by sending USS Enterprise into the Indian Ocean.[133][134][135]

- The United States did not support Pakistan during the Kargil War, and successfully pressured the Pakistani administration to end hostilities.[31][136][137]

In popular culture

Summarize

Perspective

These wars have provided source material for both Indian and Pakistani film and television dramatists, who have adapted events of the war for the purposes of drama and to please target audiences in their nations.

Indian films

- Hindustan Ki Kasam, a 1973 Hindi war film based on Operation Cactus Lilly of the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, directed by Chetan Anand.

- Aakraman, a 1975 Hindi war film based on the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war, directed by J. Om Prakash.

- Vijeta, a 1982 Hindi film based on the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war, produced by Shashi Kapoor and directed by Govind Nihalani.

- Param Vir Chakra, a 1995 Hindi film based on Indo-Pakistani War, directed by Ashok Kaul.[142]

- Border, a 1997 Hindi war film based on the Battle of Longewala of the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war, directed by J.P.Dutta.

- LOC Kargil, a 2003 Hindi war film based on the Kargil War, directed by J. P. Dutta.

- Deewaar, a 2004 Hindi film starring Amitabh Bachchan based on the POW of the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war, directed by Milan Luthria.

- Lakshya, a 2004 Hindi film partially based on the events of the Kargil War, directed by Farhan Akhtar.

- 1971, 2007 Hindi war film based on a true story of prisoners of war after the Indo-Pakistani war of 1971, directed by Amrit Sagar.

- Kurukshetra, a 2008 Malayalam film starring Mohanlal based on Kargil War, directed by Major Ravi.

- Tango Charlie, a 2005 Hindi film starring Ajay Devgan, and Bobby Deol based on Kargil Conflict, directed by Mani Shankar.

- The Ghazi Attack, a 2017 Telugu and Hindi bilingual film based on the sinking of PNS Ghazi.

- 1971: Beyond Borders, a 2017 Malayalam film, directed by Major Ravi.

- Raazi, a 2018 Hindi film about an Indian spy during the Indo Pakistan war of 1971, directed by Meghna Gulzar

- Uri: The Surgical Strike, a 2019 Hindi film about India's surgical strike into the Pakistani base camps after the Uri incident in 2016.

Pakistani films, miniseries and dramas

- Angaar Waadi, an Urdu drama serial based on the Kashmir conflict, directed by Rauf Khalid[143]

- Laag, an Urdu drama serial based on the Kashmir conflict, directed by Rauf Khalid[143]

- PNS Ghazi (Shaheed), an Urdu drama based on sinking of PNS Ghazi, ISPR

- Alpha Bravo Charlie, an Urdu drama serial based on three different aspects of Pakistan Army's involvement in action, directed by Shoaib Mansoor

- Sipahi Maqbool Hussain, an Urdu drama serial based on a 1965 war POW, directed by Haider Imam Rizvi

See also

Notes

- "The death toll remains disputed with figures ranging from 200,000 to 2 million."[6]

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.