Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

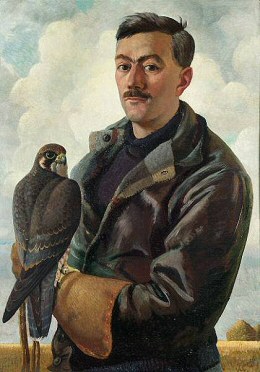

Henry Williamson

English novelist and nature writer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Henry William Williamson (1 December 1895 – 13 August 1977) was an English writer who wrote novels concerned with wildlife, English social history, ruralism and the First World War. He was awarded the Hawthornden Prize for literature in 1928 for his book Tarka the Otter.

He was born in London, and brought up in a semi-rural area where he developed his love of nature, and nature writing. He fought in the First World War and, having witnessed the Christmas truce and the devastation of trench warfare, he developed first a pacifist ideology, then fascist sympathies. He moved to Devon after the Second World War and took up farming and writing; he wrote many other novels. He married twice. He died in a hospice in Ealing in 1977, and was buried in North Devon.

Remove ads

Early years

Henry Williamson was born in Brockley in south-east London to bank clerk William Leopold Williamson (1865–1946) and Gertrude Eliza (1867–1936; née Leaver).[1] In early childhood his family moved to Ladywell, and he received a grammar school education at Colfe's School. The then semi-rural location provided easy access to the Kent countryside, and he developed a deep love of nature throughout his childhood.[2]

Remove ads

First World War

Summarize

Perspective

On 22 January 1914, Williamson volunteered as a rifleman with the 5th (City of London) Battalion of the London Regiment, part of the British Army's Territorial Force, and was mobilised when war was declared upon Imperial Germany on 4 August 1914.

In November 1914, he went to France with the London Rifle Brigade's 1st Battalion, entering the Western Front's trenches in the Ypres Salient, where he witnessed the Christmas Truce between British and German troops. In January 1915, he was withdrawn from the winter trenches with trench foot and dysentery and evacuated back to Britain. After convalescence, he was commissioned on 10 April 1915[3] as a second lieutenant with the 10th (Service) Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment. In May 1915, he was attached for training to the 2/1st Cambridgeshire Regiment at Newmarket. In October 1915, he was transferred to the 25th Middlesex Regiment at Hornchurch. He volunteered to specialise in machine-gun warfare, and in January 1916, joined No. 208 Machine Gun Company of the Machine Gun Corps at Belton Park, Grantham. In May 1916, he entered hospital in London with anaemia, and was granted two months' medical leave. He rejoined No. 208 MGC and in February 1917 departed Britain with it for the Western Front, the unit taking the field with the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division. Williamson acted as his company's transport officer and, in June 1917, he was gassed while transporting ammunition up to the front line. He was returned to the UK, spending the next few months in military convalescent hospitals. In September 1917, he was attached for garrison duty as the adjutant of the 3rd Bedfordshire Regiment at Felixstowe. Classed B1 by an Army Medical Board, from the effects of the gas, he was judged to be unfit for active service. After a year at Felixstowe, and frustrated at the nature of garrison life, Williamson attempted to get back to front-line action in September 1918 with an application to be transferred to the Royal Air Force, but this was rejected due to his medical classification. He then applied for a transfer to the Indian Army, which was granted, but the war was ending and the order was cancelled. He spent a year afterwards on administrative duties demobilising soldiers from military camps on the south east coast of England, and was himself discharged from the army on 19 September 1919.[4]

Williamson became disgusted with what he considered to be the pointlessness of the war, blaming its causation on greed and bigotry. He became determined that Germany and Britain should never go to war again. Williamson was also powerfully influenced by the camaraderie that he had experienced in the trenches, and what he saw as the bonds of kinship that existed between the ordinary British and German soldiers.[5]

Remove ads

Early writing

Summarize

Perspective

He told of his war experiences in The Wet Flanders Plain (1929), The Patriot's Progress (1930) and in many of his books in the semi-autobiographical 15-book series A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (1951–1969).

After the war, he read Richard Jefferies' book The Story of My Heart[6] and this inspired him to begin writing seriously. In 1921, he moved to Georgeham, Devon, initially living in Skirr Cottage there. He married Ida Loetitia Hibbert in 1925; they had six children. One daughter, Margaret, was the first wife of the guitarist and lutenist Julian Bream.[7][8]

In 1927, Williamson published his most acclaimed book, Tarka the Otter; it won him the Hawthornden Prize in 1928, and made him enough money to pay for the wooden hut near Georgeham where he wrote many of his later books, often sitting alone there for 15 hours a day. The wooden writing hut was granted Grade II listed status by English Heritage in July 2014 because of its "historical interest".[9] Tarka also sparked a friendship with T. E. Lawrence who had similar views about the need for a lasting peace settlement in Europe.[10] Williamson was in the process of attempting to set up a meeting between Lawrence and Adolf Hitler when Lawrence was killed in a motorcycle accident.[11] Lawrence died in May 1935 shortly after receiving a telegram from Williamson, which has sparked some conspiracy theories. Williamson had developed a profound admiration for Hitler, whom he called "the only true pacificist in Europe", and believed that the key for peace in Europe was giving leadership to the veterans of the Great War.[12] In a letter to the editor of Time and Tide in May 1936, Williamson called Hitler "a very wise and steadfast and truth-perceiving father of his people; a man like T.E. Lawrence, without personal ambitions, a vegetarian, non-smoker, non-drinker, without even a bank-balance".[12] Williamson claimed on the Night of the Long Knives in 1934 that Hitler was "actually in tears as he waited in the room", much like Lawrence "when he had to shoot an Arab murderer with his own hands".[11]

He developed the idea that "politicians" and "pettifogging lawyers" were standing in the way of peace, and all that was needed to prevent another world war was to arrange meetings between British and German veterans, who presumably would be able to settle all of the great questions of the day.[13] Williamson wrote: "The German ex-Service man respected the English ex-Service man. The English ex-Service man respected the German ex-Service man, and the German ex-Service men were in power in Germany".[14] He devised the idea of a rally at the Royal Albert Hall in London to be attended by veterans from Britain, France and Germany, where Lawrence would have been the keynote speaker.[14] He rather naively believed that such a rally would create an unstoppable movement for peace in Europe.[14] Williamson had been very influenced by the Christmas truce of 1914, which led him to the idea that the British and German veterans had common values along with the elitist idea that the veterans constituted the natural ruling class of Europe.[14] Like many other veterans, Williamson believed in the "aristocracy of the trenches", believing that the men who fought in the war were an elite, men who were tougher, braver, and more hardier than anyone else along with being more honorable and noble.[14] As the leadership of the National Socialist German Worker's Party was almost entirely made up of veterans, he was strongly attracted to Nazism as an example of veterans in power.[14]

In 1936, he bought a farm in Stiffkey, Norfolk. The Story of a Norfolk Farm (1941) is his account of his first years of farming there.

Remove ads

Politics

Summarize

Perspective

In 1935, Williamson visited the National Socialist German Workers Party Congress at Nuremberg and was greatly impressed, particularly with the Hitler Youth movement, which he viewed as having a healthy outlook on life compared with the London slums.[15] He had a "well-known belief that Hitler was essentially a good man who wanted only to build a new and better Germany."[16] Opposed to war and believing that wars were caused by Jewish "usurial moneyed interests",[17] he was attracted to Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascists and joined it in 1937.[18] Mosley became Hereward Birkin in Williamson's A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (possibly a reference to Hereward the Wake and Freda May Birkin, or possibly a reference to Chattie Wake who married Michel Hewitt Salaman who became master of the Exmoor Hunt 1908-11-see Piers P Read's biography of Alec Guinness).[citation needed] During the Danzig crisis, Williamson believed if he could end the crisis peacefully by meeting Hitler as he wrote in August 1939: "If I could see him, as a common soldier who had fraternised, on that faraway Christmas Day of 1914, with the men of his Linz battalion under Messines Hill, might I not be able to give him the amity he so desired from England, a country he admired?"[19] Williamson misapprehended, as in fact Hitler was against the Christmas truce at the time and did not take part in it himself.[20]

On the day of the British declaration of war in 1939, Williamson suggested to friends that he might fly to Germany to speak with Hitler to persuade him away from war. Following a meeting with Mosley later that day, however, he was dissuaded from his plan.[21] In June 1940, Williamson was briefly held under Defence Regulation 18B as a member of the British Union of Fascists.[22][23] Williamson was very unpopular during the war for his pro-Nazi views, which made him into an outcast.[24] Visiting London in January 1944, he observed with satisfaction that what he perceived as the ugliness and immorality represented by its financial and banking sector had been "relieved a little by a catharsis of high explosive" and somewhat "purified by fire". In The Gale of the World, the last book of his Chronicle, published in 1969, Williamson has his main character Phillip Maddison question the moral and legal validity of the Nuremberg Trials.[2]

Williamson initially retained a close relationship with Mosley in the immediate aftermath of the war, but when he brought Mosley as his guest to the Savage Club, the former BUF leader was asked to leave.[25] Williamson refused Mosley's invitation that he join the newly established Union Movement and indeed, his suggestion to Mosley that Mosley should instead join him in abandoning politics altogether led to the two men falling out.[26] Nonetheless, Williamson would write for the Mosleys' theoretical journal The European.[27] He also continued to express admiration after the war for aspects of Nazi Germany.[28]

Remove ads

Post-war life and writing

Summarize

Perspective

After the war, the family left the farm. In 1946 Williamson went to live alone at Ox's Cross, Georgeham in North Devon, where he built a small house in which to write. In 1947 Henry and Loetitia divorced. Williamson fell in love with a young teacher, Christine Duffield, and they were married in 1949. He began to write his series of fifteen novels collectively known as A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. In 1950, the year his only child by this marriage Harry Williamson was born, he edited a collection of poems and short stories by James Farrar, a promising young poet who had died, at the age of 20, in the Second World War. From 1951 to 1969 Williamson produced almost one novel a year while contributing regularly to the Sunday Express and The European magazine, edited by Diana Mosley. He also contributed a number of reviews and articles to The Sunday Times.

In 1964 he had a short affair with the novelist Ann Quin, who was nearly forty years his junior (he had previously had an affair with his secretary Myfanwy Thomas, daughter of poet Edward Thomas). All this put great strain on his marriage and, in 1968, Christine and he were divorced after years of separation.[29]

For the 1972 BBC television programme The Vanishing Hedgerows produced by David Cobham, Williamson returned to the Norfolk farm he ran for 10 years from 1936 and contrasted traditional methods of agriculture with those of the 1970s.[30]

In 1974 he began working on a script for a film treatment of Tarka the Otter to be made by Cobham, but it was not regarded as suitable to film, being about 180,000 words long.[31] Filming went on, unbeknownst to him,[citation needed] and the film of Tarka the Otter, narrated by Peter Ustinov, was released in 1979. Williamson's son Harry composed music for the film with Anthony Phillips but it was not used due to budgetary considerations; their Tarka was finished and released in 1988.

Remove ads

Death

After a general anaesthetic for a minor operation, Williamson's health failed catastrophically; one day he was walking and chopping wood, the next day he was unrecognisable and had forgotten who his family were. Suffering from dementia, he moved into a hospice at Twyford Abbey in Ealing. He died there on 13 August 1977, by coincidence on the day that the death scene of Tarka was being filmed. His body was buried in the graveyard of St George's Church, Georgeham, North Devon.[29] At a service of thanksgiving in St Martin-in-the-Fields, Ted Hughes delivered the memorial address.[32]

Remove ads

Henry Williamson Society

The Henry Williamson Society was founded in 1980. His first wife, Loetitia, supported the society until her death in 1998 and his son, Richard, is its president.[33]

Works

Summarize

Perspective

The Flax of Dream

A tetralogy following the life of Willie Maddison.

- The Beautiful Years (1921)

- Dandelion Days (1922)

- The Dream of Fair Women (1924)

- The Pathway (1928)

A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight

A sequence of fifteen novels following the life of Phillip Maddison from his birth in the late 1890s till the early 1950s. The books were based loosely on Williamson's own life and experiences. If considered as one novel, it is one of the longest in English.

- The Dark Lantern (1951)

- Donkey Boy (1952)

- Young Phillip Maddison (1953)

- How Dear Is Life (1954)

- A Fox Under My Cloak (1955)

- The Golden Virgin (1957)

- Love and the Loveless (1958)

- A Test to Destruction (1960)

- The Innocent Moon (1961)

- It Was the Nightingale (1962)

- The Power of the Dead (1963)

- The Phoenix Generation (1965)

- A Solitary War (1967)

- Lucifer Before Sunrise (1967)

- The Gale of the World (1969)

Other works

- The Lone Swallows (1922)

- The Peregrine's Saga, and Other Stories of the Country Green (1923)

- The Old Stag (1926)

- Tarka the Otter (1927)

- The Linhay on the Downs (1929)

- The Ackymals (1929)

- The Wet Flanders Plain (1929)

- The Patriot's Progress (1930)

- The Village Book (1930)

- The Labouring Life (1932)

- The Wild Red Deer of Exmoor (1931)

- The Star-born (1933)

- The Gold Falcon or the Haggard of Love (1933)

- On Foot in Devon (1933)

- The Linhay on the Downs and Other Adventures in the Old and New Worlds (1934)

- Devon Holiday (1935)

- Salar the Salmon (1935)

- Goodbye West Country (1937)

- The Children of Shallowford (1939)

- The Story of a Norfolk Farm (1941)

- Genius of Friendship: T. E. Lawrence (1941; reprinted by the Henry Williamson Society 1988; e-book 2014)

- As the Sun Shines (1941)

- The Incoming of Summer (undated)

- Life in A Devon Village (1945)

- Tales of a Devon Village (1945)

- The Sun in the Sands (1945)

- The Phasian Bird (1948)

- The Scribbling Lark (1949)

- Tales of Moorland and Estuary (1953)

- A Clear Water Stream (1958)

- In The Woods, a biographical fragment (1960)

- The Scandaroon (1972)

Writings published posthumously by the Henry Williamson Society

- Days of Wonder (1987; e-book 2013)

- From a Country Hilltop (1988; e-book 2013)

- A Breath of Country Air (2 vols, 1990–91; e-book 2013)

- Spring Days in Devon, and Other Broadcasts (1992; e-book 2013)

- Pen and Plough: Further Broadcasts (1993; e-book 2014)

- Threnos for T.E. Lawrence and Other Writings (1994; e-book 2014)

- Green Fields and Pavements (1995; e-book 2013)

- The Notebook of a Nature-lover (1996; e-book 2013)

- Words on the West Wind: Selected Essays from The Adelphi (2000; e-book 2013)

- Indian Summer Notebook: A Writer's Miscellany (2001; e-book 2013)

- Heart of England: Contributions to the Evening Standard 1939-41 (2003; e-book 2013)

- Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer: Contributions to the Daily Express 1937-39 (2004; e-book 2013)

- Stumberleap, and other Devon Writings: Contributions to the Daily Express and Sunday Express, 1915-1935 (2005; e-book 2013)

- Atlantic Tales: Contributions to the Atlantic Monthly 1927-1947 (2007; e-book 2013)

Remove ads

Sources

- Farson, Daniel, Henry: An Appreciation of Henry Williamson. London, Michael Joseph. 1982. ISBN 0-7181-2122-8

- Higginbottom, Melvyn David, Intellectuals and British Fascism: A Study of Henry Williamson. London, Janus Publishing Co. 1992. ISBN 1-85756-085-X

- Griffiths, Richard (1980). Fellow Travellers of the Right British Enthusiasts for Nazi Germany, 1933-9. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lamplugh, Lois, A Shadowed Man: Henry Williamson 1895-1977. 2nd revised ed., Dulverton, Somerset, Exmoor Press, 1991. ISBN 0-900131-70-5

- Matthews, Hugoe, Henry Williamson. A Bibliography. London, Halsgrove. 2004. ISBN 1-84114-364-2

- Murry, John Middleton, 'The Novels of Henry Williamson', in Katherine Mansfield, and other Literary Studies. London, Constable. 1959.

- Sewell, Fr. Brocard Henry Williamson: The Man, The Writings: A Symposium. Padstow, Tabb House. 1980. ISBN 0-907018-00-9

- West, Herbert Faulkner, The Dreamer of Dreams: An Essay on Henry Williamson, Ulysses Press, 1932.

- Williamson, Anne, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic, Sutton Publishing (1995) ISBN 0-7509-0639-1. Paperback edition (1997) ISBN 0-7509-1492-0

- Williamson, Anne, A Patriot's Progress: Henry Williamson and the First World War, Sutton Publishing (1998) ISBN 0-7509-1339-8

- Wilson, Peter (ed), T. E. Lawrence. Correspondence with Henry Williamson. Fordingbridge, Hants, Castle Hill Press. 2000. (Volume IX of T. E. Lawrence Letters, edited by Jeremy Wilson)

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads