Loading AI tools

1868 opera by Ambroise Thomas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hamlet is a grand opera in five acts of 1868 by the French composer Ambroise Thomas, with a libretto by Michel Carré and Jules Barbier based on a French adaptation by Alexandre Dumas, père, and Paul Meurice of William Shakespeare's play Hamlet.[1]

| Hamlet | |

|---|---|

| Grand opera by Ambroise Thomas | |

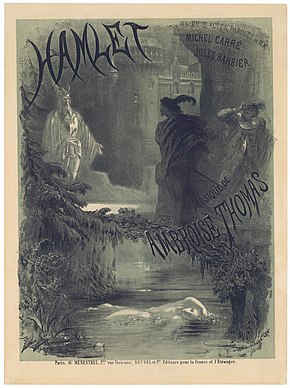

Poster for the premiere | |

| Librettist | |

| Language | French |

| Based on | French adaptation of Hamlet |

| Premiere | |

The Parisian public's fascination with Ophelia, prototype of the femme fragile,[1] began in the fall of 1827, when an English company directed by William Abbot came to Paris to give a season of Shakespeare in English at the Odéon. On 11 September 1827 the Irish actress Harriet Smithson played the part of Ophelia in Hamlet.[2]

Her mad scene appeared to owe little to tradition and seemed almost like an improvisation, with several contemporary accounts remarking on her astonishing capacity for mime. Her performances produced an extraordinary reaction: men wept openly in the theater, and when they left were "convulsed by uncontrollable emotion."[3] The twenty-five-year-old Alexandre Dumas, père, who was about to embark on a major career as a novelist and dramatist, was in the audience and found the performance revelatory, "far surpassing all my expectations".[4] The French composer Hector Berlioz was also present at that opening night performance and later wrote: "The lightning flash of that sublime discovery opened before me at a stroke the whole heaven of art, illuminating it to its remotest depths. I recognized the meaning of dramatic grandeur, beauty, truth."[2] Even the wife of the English ambassador, Lady Granville, felt compelled to report that the Parisians "roar over Miss Smithson's Ophelia, and strange to say so did I".[5] (The actress's Irish accent and the lack of power in her voice had hindered her success in London.)[3] It wasn't long before new clothing and hair styles, à la mode d'Ophélie and modeled on those of the actress, became all the rage in Paris.[1]

Not everything about the performance or the play was considered convincing. The supporting players were conceded to be weak. The large number of corpses on the stage in the final scene was found by many to be laughable. But Hamlet's interaction with the ghost of his father, the play-within-the-play, Hamlet's conflict with his mother, Ophelia's mad scene, and the scene with the gravediggers were all found to be amazing and powerful. The moment in the Play Scene when Claudius rises up and interrupts the proceedings, then rushes from the stage, provoked a long and enthusiastic ovation. The journal Pandore wrote about "that English candour which allows everything to be expressed and everything to be depicted, and for which nothing in nature is unworthy of imitation by drama".[4] Dumas felt the play and the performances provided him "what I was searching for, what I lacked, what I had to find – actors forgetting they were on stage [...] actual speech and gesture such as made actors creatures of God, with their own virtues, passions and weaknesses, not wooden, impossible heroes booming sonorous platitudes".[4]

The composer Berlioz was soon totally infatuated with Miss Smithson. His love for her, initially unrequited, became an obsession and served as inspiration for his music. His Symphonie fantastique (Fantastic Symphony, 1830) portrays an opium-induced vision in which the musician's beloved appears as a recurrent musical motif, the idée fixe, which like any obsession "finds its way into every incredible situation [movement]".[6] The Fantastic Symphony's sequel Lélio, ou Le retour à la vie (Lélio, or the Return to Life, 1831) contained a song Le pêcheur ("The Fisherman"), a setting of Goethe's ballad Der Fischer, the music of which included a quotation of the idée fixe that is associated with a siren who draws the hero to a watery grave.[7] His Tristia, Op. 18, written in the 1830s although not published until 1852, included "La mort d'Ophélie" ("The death of Ophelia"), a setting of a ballade by Ernest Legouvé, the text of which is a free adaptation of Gertrude's monologue in act 4, scene 7. Berlioz married Smithson in 1833, although their relationship ultimately fell apart.[1][8][9]

Although Harriet Smithson's stardom faded within a year and a half of her debut there,[3] the Parisian fascination with the character of Ophelia continued unabated. Besides in music, it also manifested itself in art. Auguste Préault's relief Ophélie (1844) depicted a young woman wading into water with her hair let down and swirling in the current.[1]

By the early 1840s Alexandre Dumas, who had become a personal friend of Berlioz and Smithson,[10] had achieved international fame with his historical novels and dramas. With the heightened interest in Shakespeare, and in particular Hamlet, that had been aroused by Smithson's performances at the Odéon, he decided to prepare a new French translation of the play to be presented at his Théâtre Historique. An earlier verse translation of Hamlet into French by Jean-François Ducis, first performed in 1769, was still being given at the Comédie-Française, and Dumas knew the leading role by heart. The Ducis play bore very little resemblance to the Shakespeare original. There were far fewer characters: no ghost, no Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, no players, no gravediggers. There was no duel, and Hamlet did not die at the end. Modifications such as these were necessary to gain performances in the French theaters of his time. Ducis had told the English actor-impresario David Garrick that a ghost which speaks, itinerant players, and a fencing duel were "absolutely inadmissible" on the French stage.[11] Dumas realized that Ducis' play was not the same as the original: Pierre Le Tourneur had published a relatively faithful prose translation, not intended for performance, in 1779. Nevertheless, moral propriety and politesse dictated that only such highly sanitized versions as that of Ducis could be performed on stage. The French referred to these performing editions as imitations, and most knew that they were highly modified versions of the original. All the same, Ducis was at first accused of polluting French theaters with Shakespeare; only much later was he indicted for mutilating the original.[12]

Dumas could not speak or read English well. He needed help, so he selected a younger writer by the name of Paul Meurice from among his coterie of protégés and assistants. Meurice had earlier collaborated with Auguste Vacquerie on Falstaff, a combination of Parts I and II of Shakespeare's Henry IV, which had been presented at the Odéon in 1842. The Dumas-Meurice Hamlet was performed at Dumas' Théâtre Historique in 1847 and had an enormous success. (With some alterations the Comédie-Française took it into repertory in 1886, and it continued to be performed in France until the middle of the 20th century.)[1][13]

The Dumas-Meurice version was more faithful to Shakespeare and restored much of what was missing from the Ducis version, including Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the ghost, the duel, and the gravediggers. Still, by modern standards, it was a rather free adaptation of the original. Fortinbras was dropped, and the entire opening scene with the sentinels on the ramparts of the castle was excised. A love scene between Hamlet and Ophelia was added to the first act. Claudius does not send Hamlet to England, so Rosencrantz and Guildenstern do not die. Notably, at the end of the play, as Gertrude, Claudius, and Laertes are dying, the ghost of Hamlet's father reappears and condemns each of the dying characters. To Claudius it says: Désespère et meurs! – "Despair and die!"; to Laertes: Prie et meurs! – "Pray and die!"; and to the Queen: Espère et meure! – "Hope and die!". When the wounded Hamlet asks: Et quel châtiment m'attend donc? – "And what punishment awaits me?", the ghost responds: Tu vivras! – "You shall live!", and the curtain falls.[1][14]

Dumas explained these "improvements" to Shakespeare's play by insisting that the original violated plausibility, transgressed decency, and destroyed the dramatic balance. "Since Hamlet is not guilty to the same degree as the others, he should not die the same death as the others." Four dead bodies would constitute "the most unpleasant effect." Since the ghost appears at the beginning of the play, "it must necessarily reappear to be present at the end."[15]

The librettists for the opera of Hamlet, Michel Carré and Jules Barbier, were experienced: they had already provided librettos for Thomas' Mignon and also for Gounod's Faust.[16] They chose Dumas' version of the play as the basis for their libretto. This was the version with which French audiences of the day were most familiar, and the one against which the opera would be compared and judged.[1]

When adapting a play for opera, it was imperative to shorten and simplify. Traditionally grand opera conveys plot in broad brushstrokes; the audience is not particularly interested in its intricacies, or its detours and complexities.[17] An uncut version of Shakespeare's play had more than 30 characters and could run for over four hours. The libretto reduced the total number of characters to fifteen (counting the four mime players required for the Play scene), and also reduced the number of subplots. Dumas had cut the scene with the sentinels Bernardo and Francisco. Gone also were Voltimand, Cornelius, Osric, and Reynaldo. Like Dumas, Fortinbras was omitted, thus there was no need to mention an invasion from Norway. Dumas omitted the subplot of Hamlet's voyage to England, so Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were also omitted, removing most of the black humor of the play. Polonius' accidental murder in act 4 was excised, and his singing part reduced to only eight measures.[1][16][18]

This simplification of characters and subplots focused the drama on Hamlet's predicament and its effects on Ophélie and left the opera with essentially 4 main characters: Hamlet and Ophélie, Claudius and Gertrude. This constellation of roles preserved the tetradic model and the balance of male and female parts which had become established in French grand opera at the time of Meyerbeer's Robert le diable in 1831. The libretto originally specified for these roles one soprano (Ophélie), one mezzo-soprano (Gertrude), one tenor (Hamlet), and one baritone or bass (Claudius).[1]

Other plot changes, such as making Läerte less cynical and more positive towards Hamlet early on,[19] not only simplified the story but heightened the tragedy of their duel in the Gravediggers Scene. Making Gertrude a co-conspirator alongside Claudius, enhanced the dramatic conflict between Hamlet and Gertrude when Hamlet attempts to coerce a confession from her in the Closet Scene. Making Polonius a co-conspirator, as revealed in the Closet Scene, strengthened Hamlet's motivation in rejecting his marriage to Ophélie. This crucial change facilitated the transformation of Shakespeare's Ophelia into the opera's Ophélie, a creature who dramatically is almost entirely drawn from the 19th-century, whose madness stems not from the actions of a man who creates an intolerable situation, but rather from a man whose withdrawal leaves an emptiness she is unable to fill. Musically, of course, the Mad Scene was one of those audience-pleasing creations which drew upon well-established operatic tradition.[1][20]

Another change, the addition of Hamlet's drinking song for the Players in act 2, created another opportunity for an audience-pleasing musical number. It also led to a shortening of his instructions to them before the song[16] and could be justified dramatically as a cover for his ulterior motive in asking them to enact the mime play.[21] In the final scene, in another simplification of the plot, Laërte, Polonius, and Gertrude survive. As in the Dumas' play, the ghost returns at the end, but unlike in Dumas, the ghost merely banishes Gertrude to a convent for her role in the conspiracy. Finally, exactly as in Dumas, Hamlet lives and is proclaimed King.[21]

Very little is known concerning the details of the composition of the music. Thomas may have received the libretto around 1859. The original libretto was in four acts, but the requirements of the authorities at that time specified the premiere at the Paris Opera of at least one 5-act opera per season.[1] The inclusion of a ballet was also obligatory.[22] The fourth and final act, which included the Mad Scene and the Gravediggers Scene, was simply split into two. To confer more weight to the new fourth act, the ballet was added between the choral introduction of the Mad Scene and Ophélie's recitative and aria.[1]

In 1863 the director of the Opéra, Émile Perrin, wrote in a letter to a minister of state that Thomas had nearly finished writing the music. Later the press conjectured as to the reason for the delay of the opera, suggesting that Thomas had yet to find his ideal Ophélie.[1] Thomas' opera Mignon (1866), an adaptation of Goethe's novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, had been the composer's very effective response to Gounod's earlier Goethe adaption, the opera Faust, which had premiered in 1859. Mignon had been performed at the Opéra-Comique, and Thomas was under pressure to provide a similar success at the Opéra, in particular as several of his earlier productions there had done poorly.[23]

When Gounod's Shakespeare adaptation, the opera Roméo et Juliette, appeared at the Théâtre Lyrique in 1867, it provided additional impetus for Thomas to finish working on his own adaptation of Hamlet.[24] According to accounts in the press, it was that same year, at his publisher Heugel's office in Paris, that Thomas met the Swedish soprano Christina Nilsson, who had just been engaged at the Opéra. Thomas finally consented to the scheduling of the premiere. Consistent with this press report, parts of the soprano role were altered around this time with Nilsson's capabilities in mind. Thomas replaced a dialog with the women's chorus in the Mad Scene in act 4 with a Swedish Ballade.[1] The ballad is Neck's Polska, "Deep in the sea” (in Swedish Näckens Polska, “Djupt i hafvet”) with lyrics by Arvid August Afzelius. The tune is a traditional Swedish folk tune.[25] The ballad is well known in all the Nordic countries, and is also used the first Danish national play Elves' Hill, Deep in the sea (in Danish Elverhøj “Dybt i havet”).[citation needed][26][27][circular reference] The Ballade resembles the first movement of Grieg's Op. 63 (Two Nordic Melodies), and its use was suggested to Thomas by Nilsson.[18]

A tenor suitable for the role of Hamlet could not be found, but an outstanding dramatic baritone, Jean-Baptiste Faure, was available, so Thomas decided to transpose the part, originally written for a tenor, to baritone. In the event, Faure "achieved a tremendous personal triumph as Hamlet."[23]

The work was premiered at the Paris Opera (Salle Le Peletier) on 9 March 1868. Among the noted singers in the original cast were Jean-Baptiste Faure as Hamlet and Christine Nilsson as Ophelia.[28] The opera was staged, sung in Italian, at the Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden (later the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden) in June 1869, with Nilsson as Ophelia and Charles Santley as Hamlet.[29] Hamlet was Thomas's greatest success, along with Mignon, and was further staged in Leipzig, Budapest, Brussels, Prague, New York City, Saint Petersburg, Berlin, and Vienna within five years of the Paris premiere.

The changes to Shakespeare's version of the story led to criticism of the opera in London. For instance, in 1890 a critic with The Pall Mall Gazette wrote:

No one but a barbarian or a Frenchman would have dared to make such a lamentable burlesque of so tragic a theme as Hamlet.[30]

Hamlet (Vienna, 1874), an operetta by Julius Hopp, who adapted many of Offenbach's works for the Austrian capital, is a comic parody of Thomas's artistic methods in the opera.[31]

Baritone Titta Ruffo performed the title role with bass Virgilio Lazzari as Claudius and Cyrena van Gordon as Gertrude for both the opera's Chicago premiere and on tour to New York City with the Chicago Opera Association in 1921.[32] Afterwards, the opera fell into neglect.

However, since 1980, interest in the piece has increased, and the work has enjoyed a notable number of revivals, including Sydney, with Sherrill Milnes in the title role (1982), Toronto (1985), Vienna (1992–1994, 1996), Opera North (1995),[33] Geneva (1996), San Francisco Opera (1996), Copenhagen (1996 and 1999), Amsterdam (1997), Karlsruhe (1998), Washington Concert Opera (1998), Tokyo (1999), Paris (2000), Toulouse (2000), Moscow (2001), Prague (2002), Opera Theatre of Saint Louis (2002), London (2003),[34] and Barcelona (2003, DVD available). The latter production (first shown in Geneva) was presented at the Metropolitan Opera in 2010.[35] The Washington National Opera's 2009/2010 season also featured a production of Hamlet and the Opéra de Marseille presented the work in 2010 with Patrizia Ciofi. The Minnesota Opera presented it during its 2012/13 season the same year as La Monnaie, in Brussels, with Stéphane Degout in the leading role. The same Stéphane Degout sang Hamlet in Paris, at Opera Comique, in December 2018.[36]

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast,[37][38] 9 March 1868 Conductor: François George-Hainl |

|---|---|---|

| Hamlet, Prince of Denmark | baritone | Jean-Baptiste Faure |

| Gertrude, Queen of Denmark, widow of King Hamlet and mother to Prince Hamlet |

mezzo-soprano | Pauline Guéymard-Lauters |

| Claudius, King of Denmark, brother of the late King Hamlet |

bass | Jules-Bernard Belval |

| Ophélie, daughter of Polonius | soprano | Christine Nilsson |

| Laërte, son of Polonius | tenor | Collin |

| Marcellus, friend of Hamlet | tenor | Grisy |

| Horatio, friend of Hamlet | bass | Armand Castelmary[39] |

| Ghost of the late King Hamlet | bass | David |

| Polonius, court chancellor | bass | Ponsard |

| First gravedigger | baritone | Gaspard |

| Second gravedigger | tenor | Mermant |

| Chorus: lords, ladies, soldiers, servants, players, Danish peasants | ||

Scene 1: The Coronation Hall

The royal Danish court is celebrating the coronation of Queen Gertrude who has married Claudius, brother of the late King Hamlet. Claudius places the crown on Gertrude's head. All leave, and Prince Hamlet, son of the late King and Gertrude, enters. He is upset that his mother has remarried so soon. Ophélie enters, and they sing a love duet. Laërte, Ophélie's brother, enters. He is being sent to Norway and gives his farewells. He entrusts Ophélie to the care of Hamlet. Hamlet refuses to join Laërte and Ophélie as they leave to join the banquet, and goes off in another direction. Courtiers and soldiers, on their way to the banquet, enter the hall. Horatio and Marcellus tell the soldiers that they have seen the ghost of Hamlet's father on the ramparts of the castle the previous night and go off to tell Hamlet.

Scene 2: The Ramparts

Horatio and Marcellus meet Hamlet on the ramparts. The Ghost appears, Horatio and Marcellus leave, and the Ghost tells his son that Claudius murdered him with poison. The Ghost commands Hamlet to take vengeance on Claudius, but Gertrude must be spared. The Ghost withdraws. Hamlet draws his sword and swears to avenge his father.

Scene 1: The Gardens

Ophélie, reading a book, is concerned at Hamlet's new indifference. Hamlet appears in the distance, but leaves without speaking. The Queen enters. Ophélie says she would like to leave the court, but the Queen insists she should stay. Ophélie leaves the garden and King Claudius enters. Gertrude suspects that Hamlet now knows about the murder of his father, but Claudius says he does not. Hamlet enters and feigns madness. He rejects all overtures of friendship from Claudius, then announces he has engaged a troupe of actors to perform a play that evening. Claudius and Gertrude leave, and the players enter. Hamlet asks them to mime the play The Murder of Gonzago and then sings a drinking song, playing the fool, so as not to arouse suspicion.

Scene 2: The Play

The King and Queen and the other guests assemble in the castle hall where the stage has been set up. The play begins, and Hamlet narrates. The play tells a story similar to the murder of Hamlet's father. After the "poison" is administered, the "assassin" places the "crown" on his head. Claudius turns pale, rises abruptly, and commands the play to stop and the actors to leave. Hamlet accuses Claudius of the murder of his father, and snatches Claudius' crown from his head. The entire assembly reacts in a grand septet with chorus.

Closet Scene

In the Queen's chambers Hamlet delivers the monologue "To be or not to be", then hides behind a tapestry. Claudius enters and prays aloud of his remorse. Hamlet, deciding Claudius' soul may be saved, if he is killed while praying, delays yet again. Polonius enters and in his conversation with Claudius reveals his own complicity. The King and Polonius leave, Hamlet emerges, and Gertrude enters with Ophélie. The Queen tries to persuade Hamlet to marry Ophélie, but Hamlet, realizing he can no longer marry the daughter of the guilty Polonius, refuses. Ophélie returns her ring to Hamlet and leaves. Hamlet tries to force Gertrude to confront her guilt, but she resists. As Hamlet threatens her, he sees the Ghost, who reminds him he must spare his mother.

The Mad Scene

After Hamlet's rejection, Ophélie has gone mad and drowns herself in the lake.

Gravediggers Scene

Hamlet comes upon two gravediggers digging a new grave. He asks who has died, but they do not know. He sings of remorse for his ill treatment of Ophélie. Laërte, who has returned from Norway and learned of his sister's death and Hamlet's role in it, enters and challenges Hamlet to a duel. They fight, and Hamlet is wounded, but Ophélie's funeral procession interrupts the duel. Hamlet finally realizes she is dead. The Ghost appears again and exhorts Hamlet to kill Claudius, which Hamlet does, avenging his father's death. The Ghost affirms Claudius' guilt and Hamlet's innocence. Hamlet, still in despair, is proclaimed King to cries of "Long live Hamlet! Long live the King!".

Prelude. The opera begins with a brief prelude approximately three and a half minutes in length. The music commences with soft timpani rolls, proceeds to string tremolandi, horn calls, and anguished string motifs, and "evokes the hero's tormented mind as well as the cold ramparts of Elsinore."[41]

Scene 1

A hall in the castle of Elsinore (set for the premiere designed by Auguste Alfred Rubé and Philippe Chaperon).

1. Introduction, march and chorus. The court celebrates the Coronation of Gertrude, widow of King Hamlet; and her marriage to his brother, Claudius (Courtiers: Que nos chants montent jusqu'aux cieux – "Let our songs rise to the skies"). The new king, Claudius, stands before his throne on a dais, surrounded by the nobles of the court. His court chancellor, Polonius, is nearby. Queen Gertrude enters, approaches the dais, and bows to the King (Courtiers: Salut, ô Reine bien-aimée! – "Greetings, O beloved Queen!"). Polonius hands the King a crown, which he takes and places on her head (The King: Ô toi, qui fus la femme de mon frère – "O you who were my brother's wife"). Gertrude comments in an aside to Claudius that she does not see her son Hamlet. Claudius admonishes her to bear herself as a queen. The courtiers sing of their joy as they celebrate the King and Queen's glorious marriage (Courtiers: Le deuil fait place aux chants joyeux – "Mourning gives way to joyful songs"). The King and Queen leave the hall followed by the courtiers.

2. Recitative and duet. Prince Hamlet, son of the late King and Gertrude, enters the empty hall. As Hamlet enters, before he begins singing, the low strings in the orchestra play Hamlet's Theme:[1]

|

He laments that his mother has remarried scarcely two months since his father's death (Hamlet: Vains regrets! Tendresse éphémère! – "Futile regrets! Ephemeral tenderness!").

Ophélie enters. Her entrance is accompanied by Ophélie's Theme. According to the German musicologist Annegret Fauser, Ophélie's music contrasts with Hamlet's very regular 8-bar phrase: the 4-bar theme accentuates her nervous character by the use of dotted-note rhythms, a chromatic melody line, and high-range woodwind instruments. The excerpt below ends with 3 bars of florid solo flute music which foreshadows Ophélie's coloratura singing later in the opera.[1]

|

She is worried that Hamlet's grief will blight their happiness (Ophélie: Hélas! votre âme – "Alas! your soul") and is concerned that, since Claudius has given Hamlet permission to leave, Hamlet will flee the court. Hamlet protests he cannot make promises of love one day, only to forget them the next. His heart is not that of a woman. Ophélie is distraught at the insult, and Hamlet begs forgiveness.

The duet affirms their love (Hamlet, Ophélie: Doute de la lumière – "Doubt that the light"). The text of the duet is based on Shakespeare's "Doubt thou the stars are fire", which is part of a letter from Hamlet to Ophelia which Polonius reads to Gertrude and Claudius. The melody of the vocal line in Hamlet's first phrases has been called the Theme of Hamlet's Love for Ophélie and appears several more times in the opera, with particular poignancy near the end of the Mad Scene (see below).[1]

|

The three themes which have been introduced in this number are the most important elements which Thomas uses for creating compositional and dramatic unity in the opera. They reoccur, usually in modified form, whenever significant situations relevant to the ideas they represent present themselves, although without having, in the Wagnerian sense, a leitmotivic function.[1]

3. Recitative and cavatina of Laërte. Ophélie's brother, Laërte, enters. He tells Hamlet and Ophélie that the King is sending him to the court of Norway, and he must leave that very night (unlike in the play where, as Matthew Gurewitsch of Opera News has said, he embarks for "the fleshpots of Paris").[19] In his cavatina, Laërte asks Hamlet to watch over his sister while he is gone (Laërte: Pour mon pays, en serviteur fidèle – "For my country, in faithful service"). (In the play Laertes warns Ophelia to be wary of Hamlet's intentions.) Fanfares are heard as servants and pages pass at the back. Laërte asks Hamlet and Ophélie to come with him to the banquet, but Hamlet declines. The couple separates, as Laërte and Ophélie leave for the banquet, and Hamlet goes off in the other direction. More fanfares are heard as lords and ladies enter on their way to the banquet (Lords and Ladies: Honneur, honneur au Roi! – "Honor, honor to the King!"). They are followed by a group of young officers.

4. Chorus of Officers and Pages. The officers sing of their hope that the call of pleasure will dispel their current ennui (Officers: Nargue de la tristesse! – "Scoff at sorrow"). Horatio and Marcellus enter in haste, looking for Hamlet. They tell of having seen the ghost of the late King upon the ramparts the previous night. The skeptical officers respond: "An absurd illusion! Lies and sorcery!" Undeterred, Horatio and Marcellus leave to find and warn the young prince. The officers, with the lords and ladies, finish the chorus and depart for the banquet. (Again, this scene is unlike the play in which Horatio, who has not seen the ghost himself but has merely heard of it from the sentinels, reports the news of the ghost's appearance to Hamlet directly, and not to a group of soldiers. For some reason Matthew Gurewitsch finds this change somewhat odd: "Horatio and a sidekick blab the dread news of the Ghost's appearance to a squadron of frolicking young officers, who are totally unimpressed.")[19]

Scene 2

The ramparts. At the back, the illuminated castle. – It is night. The moon is partially obscured by dense clouds (set for the premiere designed by Auguste-Alfred Rubé and Philippe Chaperon).

Prelude. The five-minute prelude sets the sinister atmosphere of the scene.

5. Scene at the ramparts. Horatio and Marcellus enter (Horatio: Viendra-t-il? – "Will he come?") and are soon followed by Hamlet (Hamlet: Horatio! n'est-ce point vous? – "Horatio! is that you?"). Horatio and Marcellus tell Hamlet that they have seen his father's ghost on the previous night at the stroke of twelve. Fanfares are heard emanating from the banquet hall within the castle, and soon thereafter the bells begin to toll midnight. The ghost appears, and they express their fear.

Invocation. Hamlet addresses the Ghost (Hamlet: Spectre infernal! Image venerée! – "Infernal apparition! Venerated image!"). The ghost gives a sign indicating that Horatio and Marcellus should withdraw, and Hamlet orders them to do so. The ghost speaks: Écoute-moi! – "Listen to me!". He identifies himself and commands Hamlet to avenge him. Hamlet asks what is the crime he must avenge, and who has committed it? Sounds of music from within the castle, fanfares, and distant cannon are heard, and the Ghost responds: "Hark: it is he they are honoring, he who they have proclaimed King! ... The adulterer has defiled my royal residence: and he, to make his treason more complete, spying upon my sleep and taking advantage of the hour, poured poison on my sleeping lips. ... Avenge me, my son! Avenge your father! ... From your mother, though, turn your anger away, we must leave punishment in the care of heaven." The ghost withdraws, his parting words: Souviens-toi! – "Remember me!" Hamlet draws his sword and proclaims his intention to obey the ghost's command (Hamlet: Ombre chére, ombre vengeresse, j'exaucerai ton vœu! ... je me souviendrai! – "Beloved shade, avenging shade, I shall fulfill your command! ... I shall remember!"). The English musicologist Elizabeth Forbes has written: "Even the composer's detractors, and there have been many, are agreed that Thomas' music for this scene is masterly; he catches the chilling, gloomy atmosphere perfectly...."[42] In his review of the recording with Thomas Hampson as Hamlet, Barrymore Laurence Scherer says "Thomas captures Hamlet's shadowy malaise in both vocal line and somber accompaniment ... The intimacy of the recording provides Thomas Hampson with ample opportunity to make the most of the relationship between words and music..."[41] The orchestral music which accompanies his vow to avenge his father's murder is another example of a theme which reoccurs multiple times at key points in the drama.[1]

|

Entr'acte. The second act begins with a musical interlude of about two minutes, which sets the scene in the garden. After some emphatic introductory orchestral chords and horn calls, harp arpeggios lead into the main section which employs the Theme of Hamlet's Love,[1] initially played by horn and strings, followed by solo horn accompanied with clarinet and flute figures reminiscent of bird calls.[43]

Scene 1

The castle gardens (set for the premiere designed by Charles-Antoine Cambon).

6. Aria of Ophélie. Ophélie is in the garden with a book in her hand. She laments Hamlet's distance, feeling his look is something like reproach (Ophélie: Sa main depuis hier n'a pas touché ma main! – "His hand has not touched mine since yesterday"). She reads from her book, at first silently, then aloud (Ophélie: "Adieu, dit-il, ayez-foi!" – "'Adieu, he said, trust me!'"). Hamlet appears on the other side of the garden. (An English horn plays the Theme of Hamlet's Love.) Hamlet sees Ophélie and tarries. Again she reads aloud from her book (Ophélie: "En vous, cruel, j'avais foi! Je vous aimais, aimez moi!" – "'In you, O cruel one, I believed. I loved you! Love me too!'"), then looks at Hamlet. However, he remains silent, then rushes away. Ophélie says ruefully: Ah! ce livre a dit vrai! – "Ah! This book spoke the truth!" and continues her aria (Ophélie: Les serments on des ailes! – "Promises have wings!").

7. Recitative and arioso. The Queen comes into the garden hoping to find Hamlet. She sees Ophélie's distress and presses her for information as to its cause (The Queen: Je croyais près de vous trouver mon fils – "I thought to find my son with you"). Ophélie says Hamlet no longer loves her and begs permission to leave the court. In the Queen's arioso, one of the finest numbers in the score,[42] she rejects Ophélie's request, saying that the barrier between Ophélie and Hamlet comes from another source (The Queen: Dans sons regards plus sombre – "In his sombre expression"). She argues that Ophélie's presence may help cure Hamlet of his madness. Ophélie says she shall obey and leaves.

8. Duet. The King now comes into the garden (The King: L'âme de votre fils est à jamais troublée, Madame – "Your son's soul is ever troubled, Madame"). The Queen suggests Hamlet may have discovered the truth, but Claudius believes he suspects nothing.

An extended version of this very short duet appears in the piano-vocal score.[44] Only the initial phrases of this passage are found in the original full score, and the section which begins with the Queen's phrase Hélas! Dieu m'épargne la honte – "Alas! may God spare me the shame" is marked as a possible cut. The scoring of the remainder of the duet was thought lost. The original manuscript with the full score of the duet was recently found at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.[42] The uncut duet is performed in the video recording with Simon Keenlyside as Hamlet.[45] It is included as an appendix in the recording with Thomas Hampson as Hamlet (see Recordings).[42]

Recitative. At the conclusion of the duet Hamlet enters, and the orchestra plays Hamlet's Theme.[46] When the 8-bar theme has concluded, the King calls to Hamlet (The King: Cher Hamlet – "Dear Hamlet"), and Hamlet responds "Sire!". Claudius asks Hamlet to refer to him as Father, but Hamlet responds that his father is dead. Claudius offers his hand, in Hamlet's father's name. There is a pause as the orchestra begins again to play Hamlet's Theme, and Hamlet responds: "His is cold and lifeless." When the theme has finished, Claudius calls Hamlet "My son...", but Hamlet angrily responds: "My name is Hamlet!", and starts to walk away. The orchestra begins Hamlet's Theme again, and Gertrude asks whether Hamlet seeks the young and beautiful Ophélie, but Hamlet responds that youth and beauty will vanish in a single day. When the orchestra has finished playing Hamlet's Theme, Claudius suggests that Hamlet may wish to travel abroad, to France and Italy, but Hamlet responds he'd rather travel, like the clouds, among the stars, amid bolts of lightning.

There is a distant sound of festive music. The theme employed is that of the Danish March (which accompanies the entrance of the royal court in the following Play Scene).[47] The King tells Hamlet to listen to the sound of the festivities and admonishes him to hold up his head. Hamlet announces he has summoned an itinerant troupe of actors to provide entertainment. Claudius agrees to this, and then says to Gertrude, "He knows nothing!", but she replies "I am afraid!" as they turn to leave. The orchestra begins to play the theme of Hamlet's Promise, and Hamlet sings: Mon pére! Patience! Patience! – "My father! Patience! Patience!".[48]

9. Recitative and chorus of comedians. Marcellus and Horatio enter with the Players (tenors and basses). Marcellus announces: Voici les histrions mandés par vous, Seigneur. – "Here are the actors you sent for, my lord." The players sing a chorus (Players: Princes sans apanages – "Princes without privilege").[49] In an aside Hamlet reveals his true purpose (Hamlet: C'est en croyant revoir se dresser sa victime que plus d'un meurtrier a confessé son crime – "In believing he sees his victim rise up, more than one murderer has confessed his crime"). He asks the players to enact the play The Murder of Gonzago, saying he shall tell them when to pour the poison. He then asks the pages to bring in wine for all.

10. Chanson Bacchique. Seizing a goblet, Hamlet sings a song in praise of wine (Hamlet: Ô vin, dissipe la tristesse qui pése sur mon cœur! À moi les rêves de l'ivresse et le rire moqueur! – "O wine, dispel the sorrow which weighs on my heart! Give me dreams of euphoria and the mocking laugh!"). In a florid cadenza it rises to a high G (G4). (An easier version with fewer notes and a lower top note, F (F4), is also included in the score.)[50] This drinking song, which is not found in Shakespeare, has been the object of much negative criticism. Edward Greenfield, on the other hand, has written that "Thomas brings off a superb dramatic coup with the most memorable of the hero's solos, his drinking song for the players...."[51]

Scene 2

The Great Hall of the castle, festively lit. The royal throne is on the right, a platform for the courtiers on the left; at the back, a small theatre, curtains closed (set for the premiere designed by Charles-Antoine Cambon).

11. Danish march. The entrance of the royal court is accompanied by a four-and-a-half minute march in alla breve time and A-B-A form which is introduced with a fanfare. The theme of the A section was first heard near the end of the trio recitative with Claudius, Hamlet, and Gertrude in the first scene of act 2. The King and Queen enter first, followed by Polonius, Ophélie, Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus, and the court.[52]

Recitative and prologue. Hamlet asks Ophélie if he may sit at her feet (Hamlet: Belle, permettez-nous – "Lady, permit me"). She responds that his expression frightens and chills her. Hamlet sits, his eyes fixed on the King and Queen. Everyone takes their places, and the curtains of the small theatre are opened. The play is introduced with a short orchestral passage featuring a saxophone solo. (According to Annegret Fauser this is the first instance of the use of a saxophone in an opera.)[53] In an aside Hamlet asks Marcellus to watch the King (Hamlet: Voici l'instant! fixez vos regards sur le Roi, et, si vous le voyez pâlir, dites-le moi! – "Now! Fix your gaze on upon the King, and, if he should turn pale, tell me!").

12. Pantomime and finale. On the small stage an aged king wearing a crown enters slowly on the arm of a queen whose features and costume are similar to those of Queen Gertrude. Hamlet, whose eyes never leave the face of King Claudius, narrates the action of the mimed play (Hamlet: C'est le vieux Roi Gonzague et la Reine Genièvre – "This is the aged King Gonzago and Queen Guinevere"). The play proceeds as follows: With protestations of love Guinevere leads Gonzago to a lonely spot. The drowsy king soon falls asleep in her arms. The villain enters. She holds out a cup, he seizes it, and pours the fatal potion, then takes the crown and places it on his head.

At this point Hamlet interrupts his narrative and addresses Claudius directly (Hamlet: Sire, vous pâlissez – "Sire, you grow pale!"). Angered and fearful, the King rises (The King: Chassez, chassez d'ici ces vils histrions! – "Expel, expel these vile minstrels!"). Hamlet, feigning madness, accuses Claudius of the murder of his father (Hamlet: C'est lui qui versait le poison! – "He's the one who poured the poison!"). Hamlet approaches the King, pushing aside the courtiers who surround him, and snatches the crown from Claudius' head (Hamlet: A bas, masque menteur! vaine couronne, à bas! – "Down with the lying mask! Down with the empty crown!").

The King, pulling himself together, solemnly declares: Ô mortelle offense! Aveugle démence, qui glace tous les cœurs d'effroi! – "O fatal insult! Blind lunacy, which chills every heart with dread!" The melody of the vocal line is a variant of the theme of Hamlet's Promise. Ophélie cries out, and the Queen declares her outrage (The Queen: Dans sa folle rage, il brave, il outrage – "In his mad rage, he defies, he offends"). These utterances of the King and the Queen begin a grand ensemble passage, "a magnificent septet",[22] which builds to a climax in which Hamlet bursts out in "mad Berlioz-like excitement"[51] with snatches of the Chanson Bacchique. At the end, Hamlet totally collapses. The King rushes out, followed by the Queen, and the entire court.

"Closet Scene"

A chamber in the Queen's apartments. At the back are two full-length portraits of the two kings. A prie-Dieu. A lamp burns on a table (set for the premiere designed by Édouard Desplechin).

Entr'acte. The act begins with a short but powerful introduction, "almost Verdian"[18] in its effect. Fortissimo French horns play the variant of Hamlet's Promise (the King's Ô mortelle offense!) which began the septet that closed act 2. The music becomes more agitated, reflecting Hamlet's highly conflicted state of mind. The trumpets sound mutated snippets of the royal court's Danish march.[1]

13. Monologue. Hamlet is alone and seated on a couch. He chastises himself for his failure to act (Hamlet: J'ai pu frapper le misérable – "I could have killed the scoundrel.") This leads to a calmer, more introspective section (Hamlet: Être ou ne pas être – "To be or not to be"), which follows the Shakespeare original closely, although greatly shortened.[19][20] He hears someone approaching (Hamlet: Mais qui donc ose ici me suivre? Le Roi!... – "But who then dares to follow me here? The King!..."). He hides behind a tapestry (arras).

14. Recitative and bass aria. The King enters. He muses to himself (The King: C'est en vain que j'ai cru me soustraire aux remords. – "In vain have I thought to escape my remorse."). The King kneels at the prie-Dieu and prays aloud (The King: Je t'implore, ô mon frère! – "I implore you, O my brother!"). Hamlet overhears and fears Claudius' remorse could yet save his soul. He therefore delays yet again, deciding that Claudius must be dispatched in drunken revels at the court. The King rises. Thinking he has seen a ghost, he calls out for Polonius. Polonius comes rushing in. The King tells him he has seen the ghost of the dead king. Polonius tries to calm the King and warns him to beware lest a word betray them both. The King rushes out followed by Polonius. Hamlet emerges from behind the tapestry (Hamlet: Polonius est son complice! le père d'Ophélie! – "Polonius is his accomplice. Ophelia's father!"). He regrets having overheard this terrible revelation.

15. Trio. Ophélie enters with the Queen. (The Queen: Le voilà! Je veux lire enfin dans sa pensée – "There he is! I must know what is on his mind"). The Queen tells Hamlet, the altar awaits him, here is his betrothed. Hamlet looks away, without replying. The Queen persists. Hamlet thinks of Polonius' perfidy (Hamlet: Sur moi tombent les cieux avant que cet hymen funeste s'accomplisse! – "May the heavens fall upon me before such an ill-fated marriage can be solemnized!"). Ophélie asks what he means. He responds: Non! Allez dans un cloître, allez, Ophélie. – "No! Go to a nunnery, go, Ophélie."). The Queen asks whether he has forgotten all Ophélie's virtues. He replies he now feels nothing in his heart. Ophélie despairs (Ophélie: Cet amor promis à genoux – "The love that on your knees you swore"). She returns her ring to him (Theme of Hamlet's Love), and Hamlet weeps. The Queen turns to Ophélie saying he weeps, he remembers, he loves you. Hamlet cries out again (Hamlet: Non! Allez dans un cloître, allez, Ophélie – "No! Go to a nunnery, go, Ophélie"). Each continues to express conflicting feelings in an extended ensemble. Ophélie leaves, hiding her tears.

16. Duet. The Queen warns Hamlet that he has offended his father, and she may be powerless to save his life (The Queen: Hamlet, ma douleur est immense! – "Hamlet, my grief is great!"). Hamlet asks, who has offended his father? She denies any understanding of his meaning. Hamlet blocks her attempt to leave, tries to force her to confront her guilt (Hamlet: Ah! que votre âme sans refuge pleure sur les devoirs trahis – "Ah! Let your defenseless heart weep over duties betrayed"). Hamlet leads his mother to the two portraits and points to the portrait of his father (Hamlet: Ici la grâce et la beauté sereines – "Here are grace and serene beauty"), then to the other portrait (Là, tous les crimes de la terre! – "There, all crimes of the earth!"). The Queen begs for mercy, kneeling before Hamlet (The Queen: Pardonne, hélas! ta voix m'accable! – Forgive me, alas! Your voice devastates me!"). The Queen collapses on a couch. The orchestra repeats the distinctive ostinato first heard in the Ramparts Scene as the accompaniment to Hamlet's aria (Spectre infernal!). The light dims, and the Ghost appears behind the couch, one arm extended toward Hamlet (Ghost: Mon fils! – "My son!"). Hamlet pulls back in confusion. The Ghost warns Hamlet (Ghost: Souviens-toi... mais épargne ta mère! – "Do not forget... but spare your mother!"). As the Ghost vanishes, the orchestra plays the theme of Hamlet's Promise, and the doors close themselves. Hamlet asks his mother not to think he is mad; his rage has calmed. He tells her to repent and sleep in peace, then leaves. She collapses at the foot of the prie-Dieu.

Elizabeth Forbes states that the final duet of act 3 represents the climax of the act and the pivotal scene of the entire opera,[20] and the act as a whole "is by far the finest of the opera, musically as well as dramatically."[42]

A pastoral spot surrounded by trees. At the back, a lake dotted with verdant islets and bordered with willows and rushes. The day breaks and floods the scene with cheerful light (set for the premiere designed by Édouard Desplechin).

17. Entr'acte. A short musical interlude of about two minutes, which features a soft, legato clarinet solo, introduces the fourth act.

Ballet: La Fête du printemps (Celebration of Spring). Divertissement.

The recording conducted by Richard Bonynge (with Sherrill Milnes as Hamlet and Joan Sutherland as Ophelia) includes the ballet music in its proper place at the beginning of act 4, but omits significant portions of it.[54] Edward Greenfield, in his review of the recording in the Gramophone magazine says the ballet music "may in principle seem an absurd intrusion in this of all operas, but … in effect provides a delightful preparation for Ophelia's mad scene".[51]

In the recording with Thomas Hampson as Hamlet, sections B–F of the ballet are included as an appendix. Elizabeth Forbes, in her essay which accompanies that recording, says: "the ballet-divertissement of La Fête du printemps (a ballet was obligatory at the Opéra in the 19th century) which opens act 4 is frankly an anti climax. … undistinguished musically and unnecessary dramatically".[20]

The video with Simon Keenlyside as Hamlet omits the entire ballet and most of its music (sections A–E).

18. Ophélie's Scene and Aria ("Mad Scene").

Recitative. The music begins with Ophélie's Theme. The peasants see a young girl approaching (Peasants: Mais quelle est cette belle et jeune demoiselle – "But who is this fair young maiden").

Ophélie enters, dressed in a long white gown and with her hair bizarrely adorned with flowers and creepers (Ophélie: A vos jeux, mes amis, permettez-moi de grâce de prendre part! – "My friends, please allow me to join in your games!"). Ophélie's opening recitative is interrupted by a florid cadenza with an ascending run up to a trill on a forte A (A5).[55]

Andante. Ophélie tells the peasants that, should they hear that Hamlet has forgotten her, they should not believe it (Ophélie: Un doux serment nous lie – "A tender promise binds us to each other"). The orchestral part features a string quartet accompaniment marked "espressivo".[56]

Waltz. This section, marked "Allegretto mouvement de Valse", begins with a short orchestral introduction. Ophélie offers a sprig of wild rosemary to a young girl and a periwinkle to another (Ophélie: Partegez-vous mes fleurs – "Share my flowers"). It concludes with an even more elaborate cadenza ending with an extended trill on F (F5), which finishes with a downward octave leap, and a quick passage ascending to the final staccato high B-flat (B♭5). In a more difficult alternative version, the trill on F finishes with an upward leap to forte high D (D6) and a quick passage descending to middle B-flat (B♭4), followed by an upward octave leap to a final forte high B flat (B♭5) which is held.[57]

|

Ballade. In the mournful Ballade, Ophélie sings about the Willis (water sprite) who lures lovers to their death, dragging them under the water until they drown (Ophélie: Et maintenant écoutez ma chanson. Pâle et blonde, dort sous l'eau profonde – "And now listen to my song. Pale and fair, sleeping under the deep water"). (The Ballade replaces Shakespeare's "Tomorrow is St. Valentine's Day", the bawdy words of which were probably considered inappropriate at the Opéra.)[20] It includes a quantity of coloratura singing, and, in the words of Matthew Gurewitsch, is "interwoven with a wordless wisp of a refrain, spun out over the nervous pulse of a drum, like birdsong from some undiscovered country."[19] The Ballade concludes with a coloratura passage that finishes with a run up to a high E (E6) and a fortissimo trill on A sharp (A5 sharp) leading to the final high B (B5).[20][58]

19. Waltz-Ballet. A short choral passage (Peasants: Sa raison a fui sans retour – "Her reason has fled, never to return") introduces an orchestral reprise of the waltz music first heard before the Ballade.

20. Finale. The final section begins with a soft woodwind chord followed by harp arpeggios with a wordless choral accompaniment à bouches fermées (similar to the "Humming Chorus" from Puccini's later opera, Madama Butterfly) which repeats the theme from Pâle et blonde. Ophélie sings: Le voilà! Je crois l'entendre! – "There he is! I think I hear him!". As she leans over the water, holding onto the branches of a willow with one hand, and brushing aside the rushes with the other, she repeats some of the words and the melody (Theme of Hamlet's Love)[1] from her love duet with Hamlet in act 1 (Ophélie: Doute de la lumière – "Doubt that the light illumines"). One sees her momentarily floating in her white gown, as the current carries her away. (The action follows Gertrude's description of Ophelia's death in Shakespeare's act 4, scene 7.)[9]

According to Elizabeth Forbes, the opera's initial success at the Opéra was undoubtedly mostly due to the spectacular vocal effects of the "Mad Scene" as executed by the original Ophélie, Christine Nilsson.[20]

The graveyard near Elsinore.

21. Song of the Gravediggers. Two gravediggers are digging a grave (First Gravedigger: Dame ou prince, homme ou femme – "Lady or prince, man or woman"). Hamlet's Theme is heard in the orchestra, and he appears in the distance and slowly approaches (both Gravediggers: Jeune ou vieux, brune ou blonde – "Young or old, dark or fair"). They drink and sing of the pleasures of wine. Hamlet asks for whom the grave is intended. The gravediggers do not remember. (After this shortened version of the gravediggers scene, the action diverges radically from that of the Shakespeare play.)

22. Recitative and arioso. Hamlet, realizing that Ophélie has gone mad, but still unaware that she is dead, begs forgiveness for his ill treatment of her (Hamlet: Comme une pâle fleur – "Like a delicate flower").

The English music critic John Steane, reviewing Simon Keenlyside's performance of this aria, wrote:

Coming after the grave-diggers' scene, it is a tender yet bitterly repentant elegy on Ophelia's death. The soliloquy has no counterpart in Shakespeare and brings out the best in both Thomas and Keenlyside. From the composer it draws on the graceful French lyricism we know from the tenor solos in Mignon, adding a more complex responsiveness to the opera-Hamlet's simpler nature. For the singer, it provides an opportunity to use the refinement of his art yet rise to phrases, high in the voice, where he can expand the riches of his tones and the most heartfelt of his feelings.[59]

Scene and recitative. Laërte appears in the distance, enveloped in a cape (Hamlet: Mais qui marche dans l'ombre? Horatio? – "Who walks in the shadows? Horatio?"). Hamlet calls out to him, and Laërte answers and comes nearer (Laërte: Vous avez frémi, Prince? ... Oui, je suis de retour; c'est moi! – "Were you afraid, Prince? ... Yes, I have returned; it is I!"). Knowing of Ophélie's death, Laërte seeks revenge, and challenges Hamlet to a duel. They fight, and Hamlet is wounded.

23. Funeral march and chorus. A funeral march is heard (Hamlet: Écoute! Quel est ce bruit de pas? – "Listen! What noise is that?"). He asks Laërte: "Who has died?" Laërte, in an aside, is amazed that Hamlet still does not know. The funeral procession appears, led by a choir of men and women (Choir: Comme la fleur, comme la fleur nouvelle – "Like a flower, like a fresh flower"). Ophélie's body is carried in; the King and Queen, Polonius, Marcellus, Horatio and the courtiers follow behind.

24. Finale. Hamlet finally realizes who has died (Hamlet: Ophélie! ... Morte! glacée! Ô crime! Oh! de leurs noirs complots déplorable victime! – "Ophélie! ... Dead! Cold! A crime! Oh! Lamentable victim of their black conspiracy!"). He kneels beside the body of Ophélie: "I have lost you!" As the grieving Hamlet prepares to kill himself, his father's Ghost appears, visible to everyone. The King cries out "Mercy!", and the Ghost responds: "The hour has passed! You, my son, finish what you have begun!" Hamlet cries: "Ah! Strengthen my arm to run him through. Guide my strike!" He hurls himself upon the King. The King falls. The Queen cries out "Dieu!" as the others exclaim: "The King!" Hamlet responds: "No! The murderer! The murderer of my father!" The Ghost affirms: "The crime is avenged! The cloister awaits your mother!" The King dies with the words: Je meur maudit! – "I die accursed!" The Queen begs God for forgiveness, as the Ghost declares: "Live for your people, Hamlet! God has made you King." Hamlet, in despair, sings: Mon âme est dans la tombe, hélas! Et je suis Roi! – "My spirit is in the grave, alas! And I am King!" Everyone else proclaims: "Long live Hamlet! Long live the King!" and the opera ends.

A shorter version of the Finale, in which Hamlet dies, and the Ghost does not appear, is called "le dénouement du Theâtre de Covent Garden" ("the ending for Covent Garden"). Thomas may have written it in the belief that the English would not accept an adaptation in which Hamlet lives. There is no evidence, however, that it was performed in Thomas's lifetime, either at Covent Garden or anywhere else. It appears in some German vocal scores and is included as an appendix to the recording with Thomas Hampson as Hamlet.

There is an additional ending prepared by Richard Bonynge for a performance in Sydney, Australia in 1982 in which Hamlet dies of his wound suffered in the duel with Laërte. This ending appears in the recording with Sherrill Milnes as Hamlet, conducted by Bonynge.[40]

The vocal score, published in 1868 in Paris by Heugel & Cie. (plate H. 3582), is available for download from the International Music Score Library Project web site (see this work page). The web page also includes an arrangement by Georges Bizet of the ballet music from act 4, La Fête du printemps, for piano 4 hands (Paris: Heugel & Cie., n.d., plate H. 4997–5002, 5007), as well as the complete libretto in French (edited by Calmann Lévy, published: Paris: Lévy Frères, 1887).

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.