Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Germanic dragon

Dragons in Germanic mythology From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Worm, wurm or wyrm (Old English: wyrm; Old Norse: ormr; Old High German: wurm), meaning serpent, are archaic terms for dragons (Old English: draca; Old Norse: dreki/*draki; Old High German: trahho) in the wider Germanic mythology and folklore, in which they are often portrayed as large venomous snakes and hoarders of gold. Especially in later tales, however, they share many common features with other dragons in European mythology, such as having wings.

Prominent worms attested in medieval Germanic works include the dragon that killed Beowulf, the central dragon in the Völsung Cycle – Fáfnir, Nidhogg (Old Norse: Níðhǫggr), and the great world serpent, Jǫrmungandr, including subcategories such as lindworms and sea serpents.

Remove ads

Terminology

Summarize

Perspective

Etymology

In early depictions, as with dragons in other cultures (compare Russian: zmei), the distinction between Germanic dragons and regular snakes is blurred, with both being referred to as: "worm" (Old English: wyrm; Old Norse: ormʀ → ormr; Old High German: wurm), "snake" (Old English: snaca; Old Norse: snókr, snákr; Old High German: *snako), "adder" (Old English: nǣdre; Old Norse: naðr m., naðra f.; Old High German: nātara), and more, in writing; all being old Germanic synonyms for serpent and thereof. "Worm", in Old Germanic, specifically meant "long legless animal" in general, thus extending to serpents as well as invertebrates, with the latter later becomming the primary sense in modern English, etc.[1]

The descendent term worm remains used in modern English to refer to dragons, such as those similar to snakes or without wings,[2] while the Old English form wyrm has been borrowed back into modern English to mean "dragon".[3] The word also appear archaically in the original broader sense, for example in the names for the common legless lizard: blindworm, hazelworm, slowworm, including the form deaf adder etc (compare Elfdalian: näder, nädra, "common legless lizard", from Old Norse: naðr, naðra, "adder"). The Nordic descendants of Old Norse: ormr – Danish: orm, Faroese: ormur, Icelandic: ormur, Norwegian: orm, Swedish: orm – beyond being the common word for snake in Faroese, Norwegian and Swedish, in Danish and Icelandic instead being more ambiguous with invertebrate worms, remain a poetic or archaic word for dragon and similar mythological serpentine creatures.[4][5][6][a] A similar theme can be seen in German, with surviving compositions such as Lindwurm and Tatzelwurm etc.

The word "dragon", contemporaneously also appear: Old English: draca, dræce; Old West Norse: dreki, Old East Norse: *draki; Old Swedish: draki; Old Danish: draghæ; Old High German: trahho, tracho, tracko, trakko; Middle High German: trache; Old Saxon: *drako; Middle Low German: drāke, meaning "dragon, sea serpent or sea monster" etc, stemming from Latin: dracō, meaning "big serpent or dragon", itself from Ancient Greek: δράκων (drákōn) of the same meaning.[8][9][10]

The Old West and East Norse forms differ quite remarkebly, as the Western form, dreki, features an initial e-vowel, largely unique among the Germanic forms, which otherwise feature an a-vowel, indicating an early adoption which then had time to shift, potentially from the Old English form dræce. Old Swedish, and Old Danish, both East Norse languages, instead exhibit forms on /a/: draki/draghæ, indicating a Central European root. When the term entered the East Norse language is unknown. The form "dragon", in modern English, stems from Old French: dragon, while the Germanic Old English form survives as drake.[10][9]

A poem, by 11th-century Icelandic skáld Þjóðólfr Arnórsson, manages to use all four above mentioned terms in a single poem about Sigurd the dragon slayer, based on a fight between a blacksmith and a leather worker, which Arnórsson supposedly composed spontaneously upon request:[11]

Sigurðr eggjaði sleggju / snák váligrar brákar, / en skafdreki skinna / skreið of leista heiði. / Menn sôusk orm, áðr ynni, / ilvegs búinn kilju, / nautaleðrs á naðri / neflangr konungr tangar.[12]

Translation:

The Sigurd of the sledge-hammer incited the snake of the dangerous tanning tool, and the scraping-dragon of skins slithered across the heath of feet. People were afraid of the worm clad in the covering of the sole-path, before the long-nosed king of tongs overcame the adder of ox-leather.[12]

Related are also the French guivre/vouivre (from Old French for "snake") and English wyvern (Middle English: wyver, from Old French: wivre), ultimately deriving from Latin: vīpera ("viper").[13] Other words include Knucker, a dialect word for a sort of water dragon in Sussex, England.

Written corpus

Early corpus

In the 10th century Old English epic poem Beowulf, probably composed a century or two earlier, "the dragon" is referred to as both a wyrm and a draca.[14][15] Within Beowulf, there is a story of Sigemund the Wælsing featuring a treasure-hoarding dragon slain by the aforementioned hero (paralleling Beowulf himself), and which scholars suggests comes from an older tradition of dragonslayers within Germanic pagan mythology.[16][17][18]

In the eddic poem Völuspá, dating back to the 10th century, the dragon Nidhogg (Old Norse: Níðhǫggr), is foretold to show himself at the dawn of the new world, revealing himself to be a "flying dragon" (dreki), and a "shimmering adder" (naðr), flying over the land, carrying the dead between his "feathers".

Þar kømr inn dimmi dreki fljúgandi, naðr fránn, neðan frá Niðafjǫllum. Berr sér í fjǫðrum — flýgr vǫll yfir — Níðhǫggr nái—

Translation:

There comes the dim dragon flying, a gleaming adder, below from the "waning mountains". Carrying in between the feathers — flying the land over — Nidhogg corpses does—.

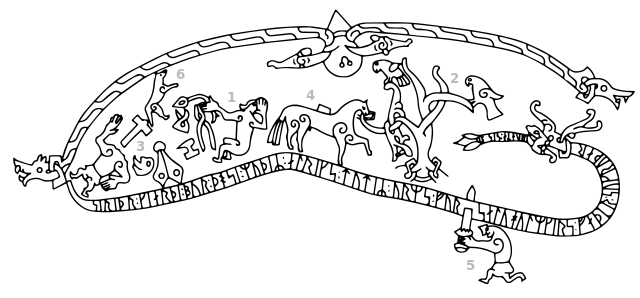

In the Middle High German epic poem Nibelungenlied, written around 1200, the unnamed dragon ("Fáfnir") is referred to as a lintrache ("lin-drake", ie, lindworm),[19] which associate professor of German, George Henry Needler (1866–1962), translated as "worm-like dragon".[20] The Old Norse Eddic poem Fáfnismál, written around 1270, tells an alternate version of the same root story as Nibelungenlied, were the dragon, Fáfnir, is described as flightless and snake-like, and is referred to as an ormr.[21][22] In the later, late 13th century Icelandic saga, Völsunga saga, Fáfnir is instead described with shoulders, suggesting legs, wings or both, and is referred to as both a dreki (dragon) and an ormr (worm).[23] Both of these descriptions are consistent with 11th century depictions of Fáfnir as a runic animal on various picture stones, sometimes being limbless and other times featuring various forms of limbs. Such stones are collectively called Sigurd stones, after Fáfnir's killer, Sigurd, who often acts as the indicator for the motif.

Later corpus

In the later, 14th century, Icelandic sagas: Ketils saga hœngs, and Konráðs saga keisarasonar, ormar and drekar are portrayed as distinct beings, with winged dragons sometimes specified as flugdreki, "flying dragon" (lit. 'fly-dragon'),[24] however, in contrast, the term flugormr, "flyging serpent", is also recorded.[25] The Icelandic written corpus still describe dragons as very serpentine-like, however. Their tail, for example, is often called a sporðr, a word for "fish tail, serpent tail and thereof" (a tail for swimming).[26][27] The 13th century saga, Bjarnar saga Hítdœlakappa, writes the following:

Síðan grípur Björn í sporðinn drekans annarri hendi en annarri hjó hann fyrir aftan vængina og gekk þar í sundur og féll drekinn niður dauður.

Translation:

Then Bjorn grabbed the dragon's tail with one hand, and with the other he slashed at the wings, which broke and the dragon fell down dead.

The later, 14th century saga, Ketils saga hœngs, specifically refers to sporðr as the tail of a serpent, and also describes the dragon as having a "coil" (lykkja) like a serpent,[28] but "wings like a dragon":

Hann hafði lykkju ok sporð sem ormr, en vængi sem dreki.

Translation:

He had a coiled body and tail like a serpent, but wings like a dragon.

The evolution of wingless and legless worms and lindworms to flying, four-legged romanesque dragons in Germanic folklore and literature is most likely due to influence from continental Europe that was facilitated by Christianisation and the increased availability of translated romances. It has thus been proposed that the description in Völuspá of Níðhöggr with feathers and flying after Ragnarök is a late addition and potentially a result of the integration of pagan and Christian imagery.[29][30][31]

Old Icelandic flugdreki was later literarily borrowed into Old Swedish as flughdraki and floghdraki, which then became a term for a Swedish type of wingless, limbless, flying dragon – Flogdrake – said to soar across the skies as a fiery or golden stripe that stretches across the sky (compare the Swedish lindworm, which lacks both limbs and wings, also the analog Slavic fiery serpents).[32][33] Old Swedish floghdraki was also, as a partial calque, borrowed into Finnish, as louhikäärme, "louhi-serpent", which later folk-etymologically morphed into lohikäärme ("salmon serpent"), Finnish for dragon.[34]

Technical terminology

To address the difficulties with categorising Germanic dragons, the term drakorm (Swedish for "dragon serpent") has been proposed, referring to beings described as either a dragon or worm.[35] Irish historian A. Walsh[b] used the term "worm-dragon" already in 1922 to describe the runic dragon like ornament found side by side with the Celtic interlaced patterns on the Cross of Cong from 1123.[2]

There are also dragon-like monsters in Germanic folklore which continue the use of worm or other synonyms in the ambiguous sense of either dragon or snake, such as lindworm (Swedish: lindorm, German: Lindwurm) and sea serpent (Swedish: sjöorm, German: Seeschlange), the latter popularized by Swede Olaus Magnus through his Carta marina (1539) and A Description of the Northern Peoples (1555), in the latter describing a sea serpent found in Bergen, Norway. Olaus gives the following description of a Norwegian sea serpent:

Those who sail up along the coast of Norway to trade or to fish, all tell the remarkable story of how a serpent of fearsome size, from 200 feet [60 m] to 400 feet [120 m] long, and 20 feet [6 m] wide, resides in rifts and caves outside Bergen. On bright summer nights this serpent leaves the caves to eat calves, lambs and pigs, or it fares out to the sea and feeds on sea nettles, crabs and similar marine animals. It has ell-long hair hanging from its neck, sharp black scales and flaming red eyes. It attacks vessels, grabs and swallows people, as it lifts itself up like a column from the water.[36][37]

Remove ads

List of Germanic dragons in legend

Summarize

Perspective

Named dragons

- Fáfnir is a widely attested dragon that has a prominent role in the Völsung Cycle.[23] Fafnir took the form of a dragon after claiming a hoard of treasure, including Andvaranaut, from his father. He was later killed by a Völsung (typically Sigurd), who in some accounts hid in a pit and stabbed him from underneath with a sword.[38][39]

- Góinn, one of the dragons at the roots of the world tree, a son of Jörmungandr, according to Grímnismál.

- Grábakr ("grayback"), one of the dragons at the roots of the world tree, a son of Jörmungandr, according to Grímnismál.

- Grafvölluðr ("grave traveller"), one of the dragons at the roots of the world tree, according to Grímnismál.

- Jörmungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent, or the "Midgard worm" (Old Norse: Miðgarðsormr), is described as a giant, venomous beast and the child of Loki and Angrboða.[31][40][41]

- King Lindworm, of Scandinavian folklore, features a lindworm as one of the main characters.

- Móinn, one of the dragons at the roots of the world tree, a son of Jörmungandr according to Grímnismál.

- Nidhogg (Níðhöggr) is a dragon attested in the Eddas that gnaws at the roots of Yggdrasil and the corpses of Náströnd.[22][41]

- Ófnir ("inciter), one of the dragons at the roots of the world tree, according to Grímnismál.

- Stoor worm ("big serpent"), a gigantic evil sea serpent of Orcadian folklore.

- Sváfnir ("sleep bringer"), one of the dragons at the roots of the world tree, according to Grímnismál.

Unnamed dragons

- In the middle of Beowulf, an unnamed treasure-hoarding dragon is killed by Sigemund the Wælsing.[42]

- An unnamed dragon is the third and last of the central monsters in Beowulf, ultimately fighting and killing the hero after whom the poem is named.[14]

- The Gesta Danorum contains a description of a dragon killed by Frotho I.[43] The dragon is described as "the keeper of the mountain." After Frotho I kills the dragon, he takes its hoard of treasure.[43]

- Also found in the Gesta Danorum is another story where Friðleifr slays a dragon with similarities to the story of Frotho I.[43][44]

Furthermore, there are many sagas with dragons in them, including Þiðreks saga, Övarr-Odds saga, and Sigrgarðs saga frækna.[45]

Local legends and tales

- Klagenfurt lindworm, Austria

- Knucker of Lyminster, England

- Lagarfljót Worm, Iceland (Icelandic: Lagarfljótsormur)

- Lambton Worm, England

- Selma (lake monster), Norway (Norwegian: Seljordsormen, "Seljord worm").

- Storsjöodjuret, Sweden

- Worm of Linton, Scotland

Remove ads

Common traits, roles and abilities

Summarize

Perspective

Guarding treasure and supernatural properties

The association between dragons and hoards of treasure is widespread in Germanic literature, however the motifs surrounding gold are absent from many accounts, including the Sigurd story in Þiðreks saga af Bern.[46]

A motif could potentially be an old myth in Germanic folklore, were it is said 'that which lies under a lindworm will grow at the rate of the snake', thus they brood over treasure to get richer. Here follows a revolving quote from Fru Marie Grubbe, by Danish author Jens Peter Jacobsen (1876), given in its Swedish (1888), and English (1917), translation, due to availability. Of note: the book does not cover mythology, rather, the segment is spontaneous and written like something commonplace for the reader, used as a parable in an otherwise unrelated story. The English translation, while fairly direct, does not use the word lindworm (Swedish: lindorm), instead opting to translate it as serpent and reptile.

In the Völsung Cycle, Fáfnir, upon claiming a hoard of treasure, including the ring Andvaranaut, transforms into a dragon to protect and brood over it. Fáfnir's brother, Regin, reforges the sword Gram from broken shards, and gives it to the hero Sigurd, who uses it to kill the dragon by hiding in a hole in its path to drink water, waiting until the worm slithers over and exposes his underbelly. While dying, Fáfnir speaks with Sigurd and shares mythological knowledge. Sigurd then cooks and tastes the dragon's heart, allowing the hero to understand the speech of birds who tell him to kill Regin, which he does and then takes the hoard for himself.[22] In the Nibelungenlied version of the story, it is said Sigurd (Sigfried) bathed in the blood of the dragon, making him invincible against all weapons, however, while bathing in the dragon's blood, a leaf fell from a tree onto his back, directly between his shoulder blades, keeping the blood from that one spot, allowing weapons to hurt him there, which later became his doom.[49] In Beowulf, it is Sigmund (the father of Sigurd in Old Norse tradition) who kills a dragon and takes its hoard.[14]

In Beowulf, the dragon slain by the poem's eponymous hero, is awoken from the burial mound in which it dwells when a cup from its hoard is stolen, leading it to seek vengeance from the Geats. After both the dragon and Beowulf die, the treasure is reinterred in the king's barrow.[14] The Old English poem, Maxims II, further states that the dragon was left in or on the mound, potentially as to increase its grave goods (Old English: frod, frætwum wlanc, "frood, treasure proud", could potentially indicate this):

In Ragnars saga loðbrókar, Thóra, the daughter of a Geatish earl, is given a snake by her father which she puts on top of a pile of gold. This makes both the snake and the treasure grow until the dragon is so large its head touches its tail.[52] The image of an encircled snake eating its own tail is also seen with Jörmungandr.[41] The hero Ragnar Lodbrok later wins the hand of Thóra and the treasure by slaying the dragon.[52] The motif of gold causing a snake-like creature to grow into a dragon is seen in the Icelandic tale of the Lagarfljót Worm recorded in the 19th century.[53]

Breathing atter and fire

Dragons with poisonous breath, or rather, breathing "atter" (so called, having an "attery breath", Old Swedish: eterblaster, lit. 'atter blast'),[54] an old Germanic word for morbid fluid, including snake venom, are believed to predate those who breathe fire in Germanic folklore and literature, consistent with the theory that Germanic dragons developed from traditions regarding wild snakes, some of whom produce venom.[23] The Nine Herbs Charm describes nine plants being used to overcome the venom of a slithering wyrm. It tells that Wōden defeats the wyrm by striking it with nine twigs, breaking it into nine pieces.[55]

In Eddic poetry, both the sea serpent Jörmungandr, and Fáfnir in dragon-hamr, are described as having attery breath.[22] In Gylfaginning, it is told that during the final battle at Ragnarök (the end of the word), Thor will kill Jörmungandr; however, after taking nine steps, he will be in turn killed by the worm's atter.[41] A similar creature from later Orcadian folklore is the attery stoor worm which was killed by the hero Assipattle, falling into the sea and forming Iceland, Orkney, Shetland and the Faroe Islands. As in the English tale of the Linton worm, the stoor worm is killed by burning its insides with peat.[56]

Beowulf is one of the earliest examples of a fire-breathing dragon, yet it is also referred to as attorsceaðan, lit. 'the atter scathe' (infinitive) or 'the atter scather'. After burning homes and land in Geatland, it fights the eponymous hero of the poem who bears a metal shield to protect himself from the fire. The dragon wounds him but is slain by the king's thane Wiglaf. Beowulf later succumbs to the dragon's atter and dies. The other dragon mentioned in the poem is further associated with fire, melting from its own heat once slain by Sigmund.[14] Both fire and atter are also spat by dragons in the Chivalric saga Sigurðr saga þögla and in Nikolaus saga erkibiskups II, written around 1340, in which the dragon is sent by God to teach an English deacon to become more pious.[23]

Atter breathing worms remained in the collective Eurpean folklore long into the second millennium. The Tatzelwurm of Alpine folklore is said to have poisonous breath. Part of a quote from Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373), which uses an atter beathing serpent as an analogy, goes:

Thy flyes hans vmgængilse swa som etirblæsandis orms[54]

Translation:

For his company flees such as that of an atter breathing serpent

Narrative importance

In Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, Tolkien argued that the only dragons of significance in northern literature are Fáfnir and that which killed Beowulf. Similarly, other scholars such as Kathryn Hume have argued that the overabundance of dragons, along with other supernatural beings, in later riddarasögur results in monsters serving only as props to be killed by heroes.[57]

Remove ads

Material culture

Summarize

Perspective

Vendel helmets

During the second half of the Germanic Migration Period, periodically called the Vendel Period (c. 540–790), spanning the late 6th century to the cusp of the Viking Age in the late 8th century, Germanic helmet finds overwhelmingly show that most helmets were decorated with dragon heads. Most common was for a dragon head to be placed between the brow protection of said helmets, with a comb spanning over the helmet as its body, but some helmets also feature dragon heads or thereof on the outer edges of the brow protection. Archeological finds of such helmets have been made in both Scandinavia and the British isles, showing a common material connection between the cultures.[58][59]

- Dragon head on the Hellvi helmet eyebrow (550–600)

- Central brow dragon head on the Vendel XIV helmet (560–575)

- Central and outer brow dragon heads on the Vendel I helmet (580–630)

- Central brow dragon heads on the Sutton Hoo helmet (613–635)

- Central and right brow dragon head on the Coppergate Helmet (8th century)

Figureheads

Longships known as "dragons" (Old Norse: drekar) were ships used by the Norse in the Medieval period that predominantly featured carved prows in the shape of dragons and other animalistic creatures.[31][60][61] One version of the Icelandic Landnámabók states that the ancient Heathen law of Iceland required any ship having a figurehead in place on one's ship "with gaping mouth or yawning snout" to remove the carving before coming in sight of land because it would frighten the landvættir.[62]

Stave churches are sometimes decorated by carved dragon heads which has been proposed to have originated in the belief in their apotropaic function.[29][63]

Picture stones

Medieval depictions of worms carved in stone feature both in Sweden and the British Isles. In Sweden, runic inscriptions dated to around the 11th century often show a lindworm bearing the text encircling the remaining picture on the stone.[64] Some Sigurd stones such as U 1163, Sö 101 (the Rasmund carving) and Sö 327 (the Gök inscription) show a Sigurd thrusting a sword through the worm which is identified as Fáfnir.[65] The killing of Fáfnir is also potentially pictured on four crosses from the Isle of Man and a now lost fragment, with a similar artistic style, from the church at Kirby Hill in England.[66][67][68]

The fishing trip described in Hymiskviða in which Thor catches Jörmungandr has been linked to a number of stones in Scandinavia and England such as the Altuna Runestone and the Hørdum stone.[69][70][71]

- Lindworm from the U 871 runestone.

- U 1163, the Drävle runestone, showing Sigurd slaying Fáfnir at the top.

- Jörmungandr on the Altuna Runestone.

Stave churches

From around the 12th century, stave churches started being erected, in Norway mostly. Such are infamous for their many wooden carvings of both Christian and Viking Age motifs, depiction varius mythological creatures, such as dragons.[73]

Wooden carvings from the Hylestad Stave Church of scenes from the Völsunga saga include Sigurd killing Fáfnir, who is notably shown with two legs and two wings.[74]

- Urnes Stave Church pillars

- Urnes Stave Church dragons

- Urnes Stave Church dragon

Remove ads

See also

- Hyrrokkin, a gýgr in Norse mythology who uses snakes as reins

- Ormhäxan, a picture stone from Gotland depicting a woman with snakes

- Runic dragon, Germanic dragons acting as the runic sling on runestones

- Biscione

Notes

- Compare Danish: da:Midgårdsormen, Icelandic: Lagarfljótsormur, Norwegian: Seljordsormen.

- "The author of Scandinavian relations with Ireland during the Viking period (Dublin, 1922) is not known for any other works. The catalogue of the British Library has two catalog records for this book and one of them lists the name as Annie. However, a review in The Geographical Journal, Vol. 62, No. 4 (Oct., 1923), as found in JSTOR, talks about Mr. Walsh." – A. Walsh – via Project Runeberg..

Remove ads

Citations

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads