Fort Kearny

United States historic place From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

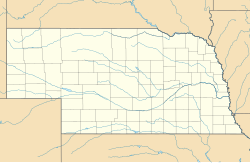

Fort Kearny was a historic outpost of the United States Army founded in 1848 in the Western United States during the middle and late 19th century. The fort was named after Colonel and later General Stephen Watts Kearny.[1] The outpost was located along the Oregon Trail near Kearney, Nebraska. The town of Kearney took its name from the fort. The "e" was added to Kearny by postmen who consistently misspelled the town name.[2] A portion of the original site is preserved as Fort Kearny State Historical Park by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission.[3]

Fort Kearney | |

Restored Fort Kearny State Park | |

| Nearest city | Newark, Nebraska |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°39′N 99°0′W |

| Area | 80 acres (32 ha) |

| Built | 1848 |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000485 |

| Added to NRHP | July 2, 1971 |

The fort became the eastern anchor of the Great Platte River Road and thus an important military and civilian way station for 20 years. Wagon trains moving west, were able to resupply after completing about a sixth (16%) of the journey. The fort offered a safe resting area for the eastern immigrants in this new and hostile land. Livestock could be traded for fresh stock and letters sent back to the states. The fort continued to expand over the years, until there were over 30 buildings before its closure in 1871. It took on additional roles as a Pony Express station, an Overland Stage station and a telegraph station.[4]

Origins and various missions of the fort

Summarize

Perspective

The fort was built in response to the growth of overland emigration to Oregon after 1845. The first post, Fort Kearny, was established in the spring of 1848 "near the head of the Grand Island" along the Platte River by Lieutenant Daniel P. Woodbury. It was first called Fort Chiles,[5] but in 1848 the post was renamed Fort Kearny in honor of General Stephen Watts Kearny.[6]

In 1848, the Pawnee Nation negotiated a major treaty with the US government at Fort Kearny. Noted diplomat Jeffrey Deroine, a formerly enslaved man, served as an interpreter for this treaty.[7][8]

Despite its lack of fortifications, Fort Kearny served as way station, sentinel post, supply depot, and message center for 49'ers bound for California and homeseekers traveling to California, Oregon and the Pacific Northwest. The earliest surviving photograph of the post, taken in 1858 by Samuel C. Mills, shows the post as a collection of adobe buildings without any wall or fortifications. By the 1860s, the fort had become a significant state and freighting station and home station of the Pony Express. During the Indian Wars of 1864–1865, a small stockade was apparently built upon the earth embankment still visible. Although never under attack, the post did serve as an outfitting depot for several Indian campaigns.

The fort was a precious source of provisions for emigrants on the early section of the trail for several decades during the height of the trail use until its abandonment in 1871. As it had been founded along the Platte River to protect emigrants on the trail westward, the fort became an important stop along the eastern part of the trail for the following decade, offering the sale of food, reliable mail service and other amenities. At the height of the pioneer trail use in the 1850s, as many as 2,000 emigrants and 10,000 oxen might pass through in a single day during the height of the trail season in late May.

One of the fort's final duties was the protection of workers building the Union Pacific. In 1871, two years after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the fort was discontinued as a military post. Its buildings were disassembled and moved West to outfit newer posts.

Description

The fort was intended mostly as a supply post, and not as defensive position in the Indian Wars. Throughout most of its history, the fort consisted mostly of wooden buildings surrounding a central parade ground without fortified walls. Throughout the decades of its use until the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the character of the buildings became slightly more permanent, changing from adobe and sod structures to wooden frame construction. Although it was in the heart of area inhabited by American Indians aka Native Americans, and was near the center of hostile action in the 1860s, no direct attack was ever made on the fort.

History

Summarize

Perspective

First Fort Kearny

The fort along the Platte River was the second of two army posts in present-day Nebraska to be named after Colonel Stephen W. Kearny of the US Army. In 1838, Kearny had scouted the area along the Missouri River at the mouth of Table Creek near present-day Nebraska City looking for a suitable location for an outpost to protect westward travelers. In 1846, following Kearny's recommendation, the United States War Department had ordered the building of an outpost on the site and directed Kearny to construct one there. The Army then sent Colonel Kearny with a detachment of men from Fort Leavenworth up the Missouri to the area with orders to construct an outpost at the selected site.[9]

The Army constructed a two-story wooden blockhouse on the site, which became known as Camp Kearny and later Fort Kearny. The Army quickly realized, however, the location was not chosen well, since few emigrants passed the site on their way west. Instead, the main routes of the trails preferred by emigrants lay to the north near Omaha and to the south. Construction was subsequently halted on the site, with the exception of the erection of a number of log huts for temporary quarters for a battalion of troops who wintered there in 1847–1848.

Second Fort Kearny

In September 1847, Kearny sent topographical engineer Lt. Daniel P. Woodbury westward along the Platte looking for a more suitable location for the outpost. Woodbury selected a site in present-day central Nebraska near the spot where the Trail westward from Independence, Missouri joined the trail westward from Omaha and Council Bluffs. Woodbury described the spot in his journals as:

- I have located the post opposite a group of wooded islands in the Platte River ... three hundred seventeen miles from Independence, Missouri, one hundred seventeen miles from Fort Kearny on the Missouri and three miles from the head of the group of islands called Grand Island.

In December Woodbury went to Washington, D.C., with orders to secure organization of the new post. Woodbury requested an appropriation of $15,000 for construction, while advocating the employment of Mormon emigrants for construction. Although he did not receive these provisions, Woodbury received permission to build the fort from scratch with soldier labor.

The Army abandoned the Table Creek post in May 1848 and arrived at the new site in June. Woodbury directed construction of the fort with 175 men as labor. They built wooden buildings around a four-acre (16,000 m2) parade ground, with cottonwood trees planted around the perimeter. Woodbury initially named the fort "Fort Childs" after Col. Thomas Childs, a famous soldier in the Mexican–American War, as well as Woodbury's father-in-law. A directive from War Department, however, directed that the name "Fort Kearny" would be transferred to the new fort.[10]

The fort grew rapidly into an important trail stop. By June 1849, Woodbury noted in his journals that 4,000 wagons had passed the fort so far that year, mostly on their way to California. The fort accumulated large stores of goods for travelers, with the directive of selling them at a beneficial cost to the emigrants. Specifically, the commander of the fort was authorized to sell goods at cost to emigrants, and in some cases of hardship, to give goods to them for free. In 1850, the fort acquired regular once-a-month mail service with the arrival of a stagecoach route between Independence, Missouri and Salt Lake City. It was the first regular mail service established along the trail.

Trail Junction

Summarize

Perspective

Fort Kearny's location was chosen based on its proximity to the junction of several existing smaller trails, which joined into a single broader route that became known as the Great Platte River Road. At this location, immigrant trains from the Missouri River trail head converged[4] and thousands of overland travelers passed by the fort each year. The Armies two functions included protection and aid to the thousands of emigrants moving westward and to protect the Indian tribes from the migrants and from other tribes. Over time, road ranches grew up nearby. Dobytown became the first settlement providing supplies and entertainment to the emigrants and the soldiers.[11]

- Eastern Trailsheads

- Westport near Kansas City, used by most emigrants.

- Fort Leavenworth

- St. Joseph, Missouri

- Nebraska City became a major freight center during The Mormon War and after the discovery of gold in the Colorado and Montana Territories (1858-1865). Freighters found the Ox-Bow Trail, with more abundant grass and water although longer and prone to having muddy lowlands. This was replaced in 1858 by the "Steam Wagon Road" which was a more direct route and improved after 1862.[12]

- Omaha, along with Florence, Nebraska, which served the Mormon Pioneers from Winter Quarters.

Role in the Indian Wars

The early years of the fort were relatively peaceful. After 1854, and the creation of the Nebraska Territory by the Kansas–Nebraska Act, the area around the fort in northern Kansas and southern Nebraska increasingly came under the hostile activity of the Cheyenne and Sioux tribes.[10] In the summer of 1864, the irritation of the Native Americans at the encroachment by white settlers culminated in violent attacks on wagon trains along the Platte and the Little Blue River. During this time, soldiers from the fort began escorting wagon trains, and the fort became a center for refugees fleeing from attacks. Earthwork fortifications were constructed at the fort, and the Army ordered the deployment of the First Nebraska Cavalry and the Seventh Iowa Cavalry to the fort. By 1865, the conflict between Native Americans and white settlers had shifted westward away from the area of the fort.[11]

Later years and abandonment

The construction of the Union Pacific Railroad across Nebraska starting in 1865 largely marked the end of the need for a fort to protect and supply wagon train emigrants. Following the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the US Army issued an order for abandonment of the post on May 22, 1871. In 1875, the buildings were torn down and the materials removed to barracks at North Platte and Sidney. The troops of the fort were restationed to Omaha and its stores were relocated to Fort McPherson 70 miles (110 km) to the west. In December 1876, the grounds were given over to the United States Department of the Interior for disbursement to settlements under the Homestead Act. Within several years, little remained of the fort except for cottonwood trees and the 1864 earthwork fortifications.[13]

Fort Kearny State Historical Park

Summarize

Perspective

In 1928, the Fort Kearny Memorial Association was formed by Nebraska citizens to raise money to purchase and restore part of the grounds. The organization was able to purchase 40 acres (16 ha) of the original site, which it offered to the State of Nebraska.[3] The State Legislature authorized the purchase, which became final on March 26, 1929. Thus acquired by the State of Nebraska in 1929, part of the original site is now operated as Fort Kearny State Historical Park by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. The site has been entered on the National Register of Historic Places.[10]

In cooperation with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, which operates the current State Historic Park, the Nebraska State Historical Society conducts ongoing archaeological investigations of the grounds. These digs have uncovered and marked the foundations of all major building on the site including headquarters, officers and troops quarters, parade grounds, storage and livestock stockade. A small theatre that shows a 20-minute history of the fort, a museum with collected artifacts and a reconstructed blacksmith shop with period cannons, caissons, tack and other equipment is behind the museum. There is space on the park for RV and trailer parking with some facilities. The park is only open during the summer months. Reenactors fire the authentic cannon every year on 4 July weekend ceremonies.

In June 2010, Governor Dave Heineman signed a Proclamation re-establishing the 2nd Battalion, Nebraska Veteran Cavalry; the unit will be at the Fort on three major holidays, Memorial Day weekend, July 4 weekend, and Labor Day weekend. This historical cavalry unit served at the fort during the Indian Wars, the unit is historically correct in every possible aspect; bugle calls used by the cavalry can be heard at differing times to announce the activities of the troop at the fort.

Depiction in fiction

Summarize

Perspective

In the novel Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne, a train in the process of being hijacked by Sioux stops at Fort Kearny to request aid from the troops there. Such an event is somewhat of an anachronism, given that the conflicts with Native Americans had largely shifted away from the area by the time of the completion of the railroad.

The fort is prominently mentioned and described as a stop along the Oregon Trail in 1855 in the novel Westward Hearts (Homeward on the Oregon Trail Book 1) by Melody Carlson, 2012 chapter 25.

Fort Kearny also appears in the short-lived television western drama series The Loner starring actor Lloyd Bridges. The series, created and written by Rod Serling of "The Twilight Zone" fame, takes place in the late 1860s and features the fort in an episode titled "Westward the Shoemaker". The "Westward..." episode concerns an Eastern European Jewish immigrant who seeks a new life in Nebraska Territory as a bootmaker but runs afoul of a card shark.

The fort is mentioned in the introduction to an episode of the TV series Wagon Train, "The Willy Moran Story" as the next destination of the settlers.

The fort is also referenced in the HBO television series Deadwood in episode 5 of the first series as the closest place to find smallpox vaccine.

The fort is mentioned in the 2014 film The Homesman, as the post Tommy Lee Jones character was stationed when a soldier with the US Dragoons.

The fort is a stop in the Oregon Trail video game.

The fort is mentioned in the Song "One Black Sheep" by Mat Kearney

The fort is featured in the series "Hell on Wheels" where the shows protagonist Cullen Bohannon was imprisoned awaiting execution but was saved by and old ally named Doc.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.