Dharavi

Slum in Maharashtra, India From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

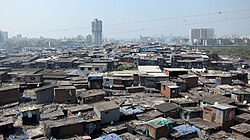

Dharavi is a residential area in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It has often been considered one of the world's largest slums.[1][2] Dharavi has an area of just over 2.39 square kilometres (0.92 sq mi; 590 acres)[3] and a population of about 1,000,000.[4] With a population density of over 418,410/km2 (1,083,677/sq mi), Dharavi is one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

Dharavi | |

|---|---|

View of Dharavi | |

Dharavi, Mumbai, Maharashtra | |

| Coordinates: 19°02′16″N 72°51′13″E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Maharashtra |

| District | Mumbai City |

| City | Mumbai |

| Founded | 1884 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal corporation |

| • Body | Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (MCGM) |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.39 km2 (0.92 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 20.47 m (67.16 ft) |

| Population (2016) | 700,000 to 1,000,000 |

| Language | |

| • Official | Marathi |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 400017 |

| Telephone code | +9122 |

| Vehicle registration | MH-01 |

| Civic agency | BMC |

The Dharavi slum was founded in 1884 during the British colonial era, and grew because of the expulsion of factories and residents from the peninsular city centre by the colonial government, and from the migration of rural Indians into urban Mumbai. For this reason, Dharavi is currently a highly diverse settlement religiously and ethnically.[5]

Dharavi has an active informal economy in which numerous household enterprises employ many of the slum residents[6]—leather, textiles and pottery products are among the goods made inside Dharavi. The total annual turnover has been estimated at over US$1 billion.[7]

Dharavi has suffered from many epidemics and other disasters, including a widespread plague in 1896 which killed over half of the population of Bombay.[8] Sanitation in the slums remains poor.[9]

History

Summarize

Perspective

In the 18th century, Dharavi was an island with a predominantly mangrove swamp.[10] It was a sparsely populated village before the late 19th century, inhabited by Koli fishermen.[11][12] Dharavi was then referred to as the village of Koliwada.[13]

Colonial era

In the 1850s, after decades of urban growth under East India Company and British Raj, the city's population reached half a million. The urban area then covered mostly the southern extension of Bombay peninsula, the population density was over 10 times higher than London at that time.[13]

The most polluting industries were tanneries, and the first tannery moved from peninsular Bombay into Dharavi in 1887. People who worked with leather, typically a profession of lowest Hindu castes and of Muslim Indians, moved into Dharavi. Other early settlers included the Kumbhars, a large Gujarati community of potters. The colonial government granted them a 99-year land-lease in 1895. Rural migrants looking for jobs poured into Bombay, and its population soared past 1 million. Other artisans, like the embroidery workers from Uttar Pradesh, started the ready-made garments trade.[11] These industries created jobs, labor moved in, but there was no government effort to plan or investment in any infrastructure in or near Dharavi. The living quarters and small scale factories grew haphazardly, without provision for sanitation, drains, safe drinking water, roads or other basic services. But some ethnic, caste and religious communities that settled in Dharavi at that time helped build the settlement of Dharavi by forming organizations and political parties, building school and temples, constructing homes and factories.[12] Dharavi's first mosque, Badi Masjid, started in 1887 and the oldest Hindu temple, Ganesh Mandir, was built in 1883 and organizing Ganesh Chaturthi of 112th year since 1913 folloing the Southern Tirunelveli Culture.[13]

Post-independence

At India's independence from colonial rule in 1947, Dharavi had grown to be the largest slum in Bombay and all of India. It still had a few empty spaces, which continued to serve as waste-dumping grounds for operators across the city.[13] Bombay, meanwhile, continued to grow as a city. Soon Dharavi was surrounded by the city, and became a key hub for informal economy.[14] Starting from the 1950s, proposals for Dharavi redevelopment plans periodically came out, but most of these plans failed because of lack of financial banking and/or political support.[12] Dharavi's Co-operative Housing Society was formed in the 1960s to uplift the lives of thousands of slum dwellers by the initiative of Shri. M.V. Duraiswamy, a well-known social worker and Congress leader of that region. The society promoted 338 flats and 97 shops and was named as Dr. Baliga Nagar. By the late 20th century, Dharavi occupied about 175 hectares (432 acres), with an astounding population density of more than 2,900 people per hectare (1,200/acre).[13][15]

Redevelopment plan

The area is a hub for around 5,000 businesses and 15,000 single-room factories across leather, textiles, pottery, metalwork, and recycling, contributing to an annual economic output estimated at over $1 billion (₹10,000 crore). Despite being an economic powerhouse, Dharavi faces significant challenges. A 2006 UNHDR report highlighted an average of one toilet for every 1,440 residents, underscoring the area's inadequate sanitation infrastructure.

There have been many plans since 1997 to redevelop Dharavi like the former slums of Hong Kong such as Tai Hang. In 2004, the cost of redevelopment was estimated to be ₹5,000 crore (US$580 million).[16] The first formal plan for Dharavi’s redevelopment was announced in 2004, but it took the government five years to act on it. When the first tender was finally released in 2009, it saw zero bids which was a sign that developers saw the project as too risky. The tender was cancelled in 2011, and the project stalled once again. Companies from around the world have bid to redevelop Dharavi,[17] including Lehman Brothers, Dubai's Limitless and Singapore's Capitaland Ltd.[17] In 2010, it was estimated to cost ₹15,000 crore (US$1.8 billion) to redevelop.[16]

In 2008 German students Jens Kaercher and Lucas Schwind won a Next Generation prize for their innovative redevelopment strategy designed to protect the current residents from needing to relocate.[18]

Other redevelopment schemes include the "Dharavi Masterplan" devised by British architectural and engineering firm Foster + Partners, that proposes "double-height spaces that create an intricate vertical landscape and reflect the community's way of life" built-in phases that the firm says would "eliminate the need for transit camps," instead catalyzing the rehabilitation of Dharavi "from within."

Sector-Based Approach Fails: 2016

The next attempt came in 2016, with a different approach which divided Dharavi into five sectors, with MHADA (Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority) handling one, while private developers were invited to bid for the remaining four. Yet, once again, no bidders came forward. Developers feared there was a low return on investment and the challenge of relocating thousands of businesses and families without resistance was a big one.[19]

The Seclink Controversy: 2018 – 2020

After the unsuccessful bid process and various concessions through the 5th November 2018 Government Resolution, the Dharavi Redevelopment Project/Slum Rehabilitation Authority came out with a tender process in November 2018. Seclink Technology Corporation (STC), a UAE-based firm emerged as the highest bidder with a bid of Rs. 7,200 crore. However, the state government was in talks with Indian Railways to acquire the 45 acres of additional land in Mahim, which posed a major roadblock in the project’s scope. This also led to a legal debate if the government should continue with the existing tender or if a fresh bidding process was required.[20]

In August 2020, the Committee of Secretaries (CoS) finally decided to cancel the 2018 Dharavi redevelopment tender, citing material changes due to the inclusion of 45 acres of railway land. This decision was based on Attorney General Ashutosh Kumbhkoni’s opinion who advised that a fresh tender was the right way to proceed. The Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) government, led by Uddhav Thackeray, approved the cancellation on October 29, 2020, and the Housing Department issued a formal resolution on November 5, 2020. Against GoM’s decision, the Highest Bidder (Seclink) filed a writ petition in the High Court, however, the High Court did not issue any stay for the fresh tender process.[21]

A Fresh Start: 2022 – 2023

In 2022, the newly elected government made significant changes to the tendering process for the fourth time. Taking the learnings from past failures, the Government of Maharashtra issued a global Request for Qualification (RFQ) and Request for Proposal (RFP) with revised terms. This time around, instead of dividing Dharavi into five sectors, the entire redevelopment was consolidated into a single Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), allowing for integrated planning and execution.[22]

Adani Wins the Bid: 2023

The fresh bidding process attracted multiple participants, but ultimately, in July 2023, Adani Properties Pvt Ltd sent out a ₹5,069 crore bid and secured the project. In the spring of 2023, it became known that the Indian billionaire Gautam Adani intends to do the reconstruction of Dharavi. Adani Properties Pvt. offers the largest amount of construction investments - 615 million dollars. Mumbai authorities estimate the total cost of the work at $2.4 billion.[23]

This is how Dharavi Redevelopment Project Private Limited (DRPPL) finally started, founded in. As of April 2024, a survey is being conducted by Adani Group to rehabilitate Dharavi residents for redevelopment.[24] On December 20, 2024, the High Court of Bombay awarded the Adani Group after the SecLink Group tried to sue.[25][26]

On March 8, 2025 the Supreme Court refused to stay the redevelopment work by Adani group based on the lawsuit by SecLink Group.[27]

Navbharat Mega Developers Private Limited

The DRPPL has since been renamed to Navbharat Mega Developers Pvt. Ltd. (NMDPL) is an SPV Company constituted to execute the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP). The Dharavi Redevelopment Project is a first-of-its-kind initiative that aims to transform the Dharavi slum into a state-of-the-art township while preserving its legacy.[28]

NMDPL operates with a strong public-private partnership model: • The Government of Maharashtra holds a 20% stake. • Adani Group holds the remaining 80% and has to bear the responsibility to invest and execute. For the first time in decades, Dharavi’s redevelopment has moved beyond paperwork and politics.[29]

Dharavi’s redevelopment has been nearly two decades in the making pushed now and then due to bureaucratic delays, failed tenders, and concerns over displacement. The land, split between BMC, Indian Railways, and state agencies, saw unplanned settlement growth and demanded immediate course correction. This is when the Government of Maharashtra introduced the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance, and Redevelopment) Act of 1971 to rehabilitate the slums rather than displace them. In 1976, the census also attempted to formalize residency through photo passes, but large-scale redevelopment remained elusive.

Demographics

Summarize

Perspective

The total current population of the Dharavi slum is unknown because of fast changes in the population of migrant workers coming from neighbouring Gujarat state, though voter turnout for the 2019 Maharashtra state legislative assembly election was 119,092 (yielding a 60% rate). Some sources suggest it is 300,000[30][31] to about a million.[32] With Dharavi spread over 200 hectares (500 acres), it is also estimated to have a population density of 869,565 people per square mile. Among the people, about 20% work on animal skin production, tanneries and leather goods. Other artisans specialise in pottery work, textile goods manufacturing, retail and trade, distilleries and other caste professions – all of these as small-scale household operations. With a literacy rate of 69%, Dharavi is the most literate slum in India.[33]

The western edge of Dharavi is where its original inhabitants, the Kolis, reside. Dharavi consists of various language speakers such as Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, and many more.[34] The slum residents are from all over India, people who migrated from rural regions of many different states.[35]

About 29% of the population of Dharavi is Muslim.[36][37] The Christian population is estimated to be about 6%,[38] while the rest are predominantly Hindus with some Buddhists and other minority religions. The slum has numerous mosques, temples and churches to serve people of Hindu, Islam and Christian faiths, with Badi Masjid, a mosque, as the oldest religious structure in Dharavi.

Location and characteristics

Dharavi is a large area situated between Mumbai's two main suburban railway lines, the Western and Central Railways. It is also adjacent to Mumbai Airport. To the west of Dharavi are Mahim and Bandra, and to the north lies the Mithi River. The Mithi River empties into the Arabian Sea through the Mahim Creek. The area of Antop Hill lies to the east while the locality called Matunga is located in the South. Due to its location and poor sewage and drainage systems, Dharavi particularly becomes vulnerable to floods during the wet season.

Dharavi is considered one of the largest slums in the world.[39] The low-rise building style and narrow street structure of the area make Dharavi very cramped and confined. Like most slums, it is overpopulated.

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

In addition to the traditional pottery and textile industries in Dharavi,[11] there is an increasingly large recycling industry, processing recyclable waste from other parts of Mumbai. Recycling in Dharavi is reported to employ approximately 250,000 people.[40] While recycling is a major industry in the neighborhood, it is also reported to be a source of heavy pollution in the area.[40] The district has an estimated 5,000 businesses[41] and 15,000 single-room factories.[40] Two major suburban railways feed into Dharavi, making it an important commuting station for people in the area going to and from work.

Dharavi exports goods around the world.[6] Often these consist of various leather products, jewellery, various accessories, and textiles. Markets for Dharavi's goods include stores in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East.[6] The total (and largely informal economy) turnover is estimated to be between US$500 million,[7] and US$650 million per year,[42] to over US$1 billion per year.[40] The per capita income of the residents, depending on estimated population range of 300,000 to about 1 million, ranges between US$500 and US$2,000 per year.

A few travel operators offer guided tours through Dharavi, showing the industrial and the residential part of Dharavi and explaining about the problems and challenges Dharavi is facing. These tours give a deeper insight into a slum in general and Dharavi in particular.[43]

Utility services

Summarize

Perspective

Potable water is supplied by the MCGM to Dharavi and the whole of Mumbai. However, a large amount of water is lost due to water thefts, illegal connection and leakage.[44] The community also has a number of water wells that are sources of non-potable water.

Cooking gas is supplied in the form of liquefied petroleum gas cylinders sold by state-owned oil companies,[45] as well as through piped natural gas supplied by Mahanagar Gas Limited.[46]

There are settlement houses that still do not have legal connections to the utility service and thus rely on illegal connection to the water and power supply which means a water and power shortage for the residents in Dharavi.

Sanitation issues

Dharavi has severe problems with public health. Water access derives from public standpipes stationed throughout the slum. Additionally, with the limited lavatories they have, they are extremely filthy and broken down to the point of being unsafe. Mahim Creek is a local river that is widely used by local residents for urination and defecation causing the spread of contagious diseases.[11] The open sewers in the city drain to the creek causing a spike in water pollutants, septic conditions, and foul odours. Due to the air pollutants, diseases such as lung cancer, tuberculosis, and asthma are common among residents. There are government proposals in regards to improving Dharavi's sanitation issues. The residents have a section where they wash their clothes in water that people defecate in. This spreads the amount of disease as doctors have to deal with over 4,000 cases of typhoid a day. In a 2006 Human Development Report by the UN, they estimated there was an average of 1 toilet for every 1,440 people.[47]

Epidemics and other disasters

Summarize

Perspective

Dharavi has experienced a long history of epidemics and natural disasters, sometimes with significant loss of lives. The first plague to devastate Dharavi, along with other settlements of Mumbai, happened in 1896, when nearly half of the population died. A series of plagues and other epidemics continued to affect Dharavi, and Mumbai in general, for the next 25 years, with high rates of mortality.[48][49] Dysentery epidemics have been common throughout the years and explained by the high population density of Dharavi. Other reported epidemics include typhoid, cholera, leprosy, amoebiasis and polio.[8][50] For example, in 1986, a cholera epidemic was reported, where most patients were children of Dharavi. Typical patients to arrive in hospitals were in late and critical care condition, and the mortality rates were abnormally high.[51] In recent years, cases of drug resistant tuberculosis have been reported in Dharavi.[52][53]

Fires and other disasters are common. For example, in January 2013, a fire destroyed many slum properties and caused injuries.[54] In 2005, massive floods caused deaths and extensive property damage.[55]

The COVID-19 pandemic also affected the slum. The first case was reported in April 2020.[56]

In the media

Summarize

Perspective

From the main road leading through Dharavi, the place makes a desperate impression. However, once having entered the narrow lanes Dharavi proves that the prejudice of slums as dirty, underdeveloped, and criminal places does not fit real living conditions. Sure, communal sanitation blocks that are mostly in a miserable condition and overcrowded space do not comfort the living. Inside the huts, it is, however, very clean, and some huts share some elements of beauty. Nice curtains at the windows and balconies covered by flowers and plants indicate that people try to arrange their homes as cosy and comfortable as possible.

— Denis Gruber et al. (2005)[57]

In the West, Dharavi was most notably used as the backdrop in the British film Slumdog Millionaire (2008).[58] It has also been depicted in a number of Indian films, including Deewaar (1975), Nayakan (1987), Salaam Bombay! (1988), Parinda (1989), Dharavi (1991), Bombay (1995), Ram Gopal Varma's "Indian Gangster Trilogy" (1998–2005), the Sarkar series (2005–2017), Footpath (2003), Black Friday (2004), Mumbai Xpress (2005), No Smoking (2007), Traffic Signal (2007), Aamir (2008), Mankatha (2011), Thalaivaa (2013), Bhoothnath Returns (2014), Kaala (2018) and Gully Boy (2019).

Dharavi, Slum for Sale (2009) by Lutz Konermann and Rob Appleby is a German documentary.[59] In a programme aired in the United Kingdom in January 2010, Kevin McCloud and Channel 4 aired a two-part series titled Slumming It[60] which centered around Dharavi and its inhabitants. The poem "Blessing" by Imtiaz Dharker is about Dharavi not having enough water. For The Win, by Cory Doctorow, is partially set in Dharavi. In 2014, Belgian researcher Katrien Vankrunkelsven made a 22-minute film on Dharavi which is entitled The Way of Dharavi.[61]

Hitman 2, a video game released in 2018, featured the slums of Mumbai in one of its missions.[62][63] The Mumbai based video game Mumbai Gullies is expected to feature the slums of Dharavi in the fictional map.[64][65][needs update]

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.