Daniel Berrigan

American poet and religious activist (1921–2016) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Daniel Joseph Berrigan SJ (May 9, 1921 – April 30, 2016) was an American Jesuit priest, anti-war activist, Christian pacifist, playwright, poet, and author.

Daniel Berrigan | |

|---|---|

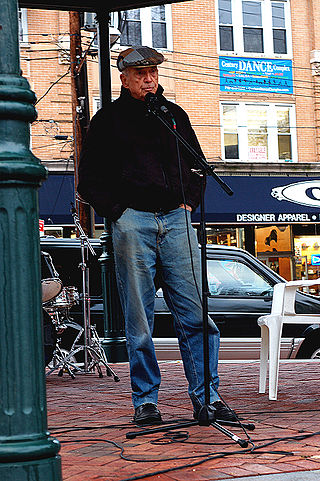

Berrigan in 2008 | |

| Born | Daniel Joseph Berrigan May 9, 1921 |

| Died | April 30, 2016 (aged 94) New York City, New York, US |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | |

| Relatives | Philip Berrigan (brother) |

| Website | danielberrigan |

Berrigan's protests against the Vietnam War earned him both scorn and admiration, especially regarding his association with the Catonsville Nine.[1][2] He was arrested multiple times and sentenced to prison for destruction of government property,[3] and was listed on the Federal Bureau of Investigation's "most wanted list" after flight to avoid imprisonment (the first-ever priest on the list).[4]

For the rest of his life, Berrigan remained one of the United States' leading anti-war activists.[5] In 1980, he co-founded the Plowshares movement, an anti-nuclear protest group, that put him back into the national spotlight.[6] Berrigan was an award-winning and prolific author of some 50 books, a teacher, and a university educator.[3]

Early life

Berrigan was born in Virginia, Minnesota, the son of Thomas Berrigan, a second-generation Irish Catholic and active trade union member, and Frieda Berrigan (née Fromhart), who was of German ancestry.[7] He was the fifth of six sons.[3] His youngest brother was fellow peace activist Philip Berrigan.[8]

At age 5, Berrigan's family moved to Syracuse, New York.[9] Berrigan was devoted to the Catholic Church throughout his youth. He joined the Jesuits directly out of high school in 1939 and was ordained to the priesthood on June 19, 1952.[3][10] In 1946, Berrigan earned a bachelor's degree from St. Andrew-on-Hudson, a Jesuit seminary in Hyde Park, New York.[11] In 1952 he received a master's degree from Woodstock College in Baltimore, Maryland.[3]

Career

Summarize

Perspective

Berrigan taught at St. Peter's Preparatory School in Jersey City from 1946 to 1949.[12]

In 1954, Berrigan was assigned to teach French and theology at the Jesuit Brooklyn Preparatory School.[13][14][15][a] In 1957 he was appointed professor of New Testament studies at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York. The same year, he won the Lamont Prize for his book of poems, Time Without Number. He developed a reputation as a religious radical, working actively against poverty and on changing the relationship between priests and lay people. While at Le Moyne, he founded its International House.[17]

While on a sabbatical from Le Moyne in 1963, Berrigan traveled to Paris and met French Jesuits who criticized the social and political conditions in Indochina. Taking inspiration from this, he and his brother Philip founded the Catholic Peace Fellowship, a group that organized protests against the war in Vietnam.[18]

On October 28, 1965, Berrigan, along with the Reverend Richard John Neuhaus and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, founded an organization known as Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam (CALCAV). The organization, founded at the Church Center for the United Nations, was joined by the likes of Doctor Hans Morgenthau, the Reverend Reinhold Niebuhr, the Reverend William Sloane Coffin, and the Reverend Philip Berrigan his brother, among many others. The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his 1967 speech Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence under sponsorship from CALCAV, served as the national co-chairman of the organization.

From 1966 to 1970, Berrigan was the assistant director of the Cornell University United Religious Work (CURW), the umbrella organization for all religious groups on campus, including the Cornell Newman Club (later the Cornell Catholic Community), eventually becoming the group's pastor.[19] Berrigan was the first faculty advisor of Cornell University's first gay rights student group, the Student Homophile League, in 1968.[20]

Berrigan at one time or another held faculty positions or ran programs at Union Theological Seminary, Loyola University New Orleans, Columbia, Cornell, and Yale.[3] His longest tenure was at Fordham (a Jesuit university located in the Bronx), where for a brief time he also served as poet-in-residence.[3][21][22]

Berrigan appeared briefly in the 1986 Warner Bros. film The Mission, playing a Jesuit priest. He also served as a consultant on the film.[23][24]

Activism

Summarize

Perspective

Vietnam War era

But how shall we educate men to goodness, to a sense of one another, to a love of the truth? And more urgently, how shall we do this in a bad time?

Berrigan, his brother and Josephite priest Philip Berrigan, and Trappist monk Thomas Merton founded an interfaith coalition against the Vietnam War and wrote letters to major newspapers arguing for an end to the war. In 1967, Berrigan witnessed the public outcry that followed from the arrest of his brother Philip, for pouring blood on draft records as part of the Baltimore Four.[26] Philip was sentenced to six years in prison for defacing government property. The fallout he had to endure from these many interventions, including his support for prisoners of war and, in 1968, seeing firsthand the conditions on the ground in Vietnam,[27] further radicalized Berrigan, or at least strengthened his determination to resist American military imperialism.[28][29]

Berrigan traveled to Hanoi with Howard Zinn during the Tet Offensive in January 1968 to "receive" three American airmen, the first American prisoners of war released by the North Vietnamese since the US bombing of that nation had begun.[30][31]

In 1968, he signed the Writers and Editors War Tax Protest pledge, vowing to refuse to make tax payments in protest of the Vietnam War.[32] In the same year, he was interviewed in the anti-Vietnam War documentary film In the Year of the Pig, and later that year became involved in radical non-violent protest.

Catonsville Nine

The short fuse of the American left is typical of the highs and lows of American emotional life. It is very rare to sustain a movement in recognizable form without a spiritual base.

Daniel Berrigan, on the 40th anniversary of the Catonsville Nine (2008)[18]

Daniel Berrigan and his brother Philip, along with seven other Catholic protesters, used homemade napalm to destroy 378 draft files in the parking lot of the Catonsville, Maryland, draft board on May 17, 1968.[33][34][35] This group, which came to be known as the Catonsville Nine, issued a statement after the incident:

We confront the Roman Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country's crimes. We are convinced that the religious bureaucracy in this country is racist, is an accomplice in this war, and is hostile to the poor.[26]

Berrigan was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison,[36] but went into hiding with the help of fellow radicals prior to imprisonment. While on the run, Berrigan was interviewed for Lee Lockwood's documentary The Holy Outlaw. The Federal Bureau of Investigation apprehended him on August 11, 1970, at the home of William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne on Block Island. Berrigan was then imprisoned at the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury, Connecticut, until his release on February 24, 1972.[37]

In retrospect, the trial of the Catonsville Nine was significant, because it "altered resistance to the Vietnam War, moving activists from street protests to repeated acts of civil disobedience, including the burning of draft cards".[2] As The New York Times noted in its obituary, Berrigan's actions helped "shape the tactics of opposition to the Vietnam War."[3]

Plowshares movement

On September 9, 1980, Berrigan, his brother Philip, and six others including Anne Montgomery RSCJ, Elmer Maas, Carl Kabat, John Schuchardt, Dean Hammer, and Molly Rush (the "Plowshares Eight") began the Plowshares movement. They trespassed onto the General Electric nuclear missile facility in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, where they damaged nuclear warhead nose cones and poured blood onto documents and files. They were arrested and charged with over ten different felony and misdemeanor counts.[38] The story is partly told in the book ARISE AND WITNESS: Poems by Anne Montgomery, RSCJ, About Faith, Prison, War Zones and Nonviolent Resistance, published in 2024.[39] On April 10, 1990, after ten years of appeals, Berrigan's group was re-sentenced and paroled for up to 231/2 months in consideration of time already served in prison.[40] Their legal battle was re-created in Emile de Antonio's 1982 film In the King of Prussia, which starred Martin Sheen and featured appearances by the Plowshares Eight as themselves.[5]

Consistent life ethic

I see an 'interlocking directorate' of death that binds the whole culture. That is, an unspoken agreement that we will solve our problems by killing people in various ways; a declaration that certain people are expendable, outside the pale. A decent society should no more have an abortion clinic than The Pentagon." — interview by Lucien Miller, Reflections, vol. 2, no. 4 (Fall 1979)[41]

Berrigan endorsed a consistent life ethic, a morality based on a holistic reverence for life.[42][43][44][45] As a member of the Rochester, New York-area consistent life ethic advocacy group Faith and Resistance Community, he protested via civil disobedience against abortion at a new Planned Parenthood clinic in 1991.[43]

AIDS activism

Berrigan said of pastoral care to AIDS patients:

We deal with very many gay Catholics who have felt terribly hurt and misused by the church. There are some people who want to be reconciled with the church and there are others who have great bitterness. So I try to perform whatever human or religious work that seems called for.[46]

Berrigan published Sorrow Built a Bridge: Friendship and AIDS reflecting on his experiences ministering to AIDS patients through the Supportive Care Program at St. Vincent's Hospital and Medical Center in 1989.[47] The Religious Studies Review wrote, "the strength of this volume lies in its capacity to portray sensitively the impact of AIDS on human lives."[48] Speaking about AIDS patients, many of whom were gay, The Charlotte Observer quoted Berrigan saying in 1991, "Both the church and the state are finding ways to kill people with AIDS, and one of the ways is ostracism that pushes people between the cracks of respectability or acceptability and leaves them there to make of life what they will or what they cannot."[49]

Other activism

Although much of his later work was devoted to assisting AIDS patients in New York City,[3] Berrigan still held to his activist roots throughout his life. He maintained his opposition to American interventions abroad, from Central America in the 1980s, through the Gulf War in 1991, the Kosovo War, the US invasion of Afghanistan, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He was also an opponent of capital punishment, a contributing editor of Sojourners, and a supporter of the Occupy movement.[50][51][52]

P. G. Coy, P. Berryman, D. L. Anderson, and others consider Berrigan to be a Christian anarchist.[53][54][55][56][57]

In media

- January 25, 1971: Featured on the cover of Time along with his brother Philip.[58]

- Adrienne Rich's poem "The Burning of Paper Instead of Children" makes numerous references to the Catonsville Nine and includes an epigraph from Daniel Berrigan during the trial ("I was in danger of verbalizing my moral impulses out of existence").[59]

- It is frequently claimed that "the radical priest" in Paul Simon's song "Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard" refers to or was inspired by Berrigan[3][42]

- Lynne Sachs's documentary film Investigation of a Flame is about the Berrigan brothers and the Catonsville Nine.[60]

- Berrigan appeared briefly in the 1986 Roland Joffé film The Mission, which starred Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons.[23][24]

- Berrigan's play The Trial of the Catonsville Nine (1970) premiered at the Lyceum Theatre in New York City on June 2, 1971. The original cast featured the talents of Biff McGuire, Michael Moriarty, Josef Sommer, Sam Waterston, and James Woods, among others. Gordon Davidson received a 1972 Tony Award nomination for his direction of the play.

- The Trial of the Catonsville Nine was adapted in a 1972 film of the same name, produced by Gregory Peck and starring Ed Flanders as Berrigan.

- Berrigan is interviewed in Emile de Antonio's 1968 Vietnam War documentary In the Year of the Pig.

- Berrigan is featured in Emile de Antonio's 1983 film In the King of Prussia, also starring fellow activist Martin Sheen.

- Berrigan appears in the 1997 documentary film An Act of Conscience, narrated by Sheen. In the film, Berrigan visits the contested home of war tax resisters Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner.[61]

- Berrigan's oral history is included in the 2006 book Generation on Fire: Voices of Protest from the 1960s by Jeff Kisseloff.[62]

- Berrigan's involvement with the Catonsville Nine is explored in the 2013 documentary Hit & Stay.

- The Chairman Dances album Time Without Measure, a nod to Berrigan’s Time Without Number, includes the song “Catonsville 9 (Thomas and Marjorie)” about the protest and the group’s expected arrest and imprisonment.[63][64]

- Dar Williams' song "I Had No Right" from her album The Green World is about Berrigan and his trial.[5]

- In the 2022 television adaptation of the podcast Slow Burn, an anti-war protester brings up the Berrigan brothers.[65]

Death

Berrigan died in the Bronx, New York City, on April 30, 2016, at Murray-Weigel Infirmary, the Jesuit infirmary at Fordham University.[3] Since 1975,[66] he had lived on the Upper West Side at the West Side Jesuit Community.[67][68]

Awards and recognition

- 1956: Lamont Poetry Selection

- 1974: War Resisters League Peace Award[69]

- 1974: Gandhi Peace Award (accepted then resigned)[70]

- 1988: Thomas Merton Award

- 1989: Pax Christi USA Pope Paul VI Teacher of Peace Award[71]

- 1991: The Peace Abbey Foundation Courage of Conscience Award[72]

- 1993: Pacem in Terris Award

- 2008: Honorary Degree from the College of Wooster[73]

- 2017: Daniel Berrigan Center at Benincasa Community, 133 W. 70th Street, New York, NY 10023

See also

Notes

- According to Marsh and Brown, it was French and philosophy.[16]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.