Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Carlo-francoism

Branch of Carlism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Carlo-francoism (Spanish: carlofranquismo, also carlo-franquismo) was a branch of Carlism which actively engaged in the regime of Francisco Franco. Though mainstream Carlism retained an independent stand, many Carlist militants on their own assumed various roles in the Francoist system, e.g. as members of the FET y de las JONS executive, Cortes procuradores, or civil governors. The Traditionalist political faction of the Francoist regime issued from Carlism particularly held tight control over the Ministry of Justice. They have never formed an organized structure, their dynastical allegiances remained heterogeneous and their specific political objectives might have differed. Within the Francoist power strata, the carlo-francoists remained a minority faction that controlled some 5% of key posts; they failed to shape the regime and at best served as counter-balance to other groupings competing for power.

This article possibly contains original research. (March 2024) |

In Spanish the term appears in scientific narrative,[1] though it is mostly used as a derogatory designation intended to stigmatize and abuse;[2] the related name of carlofranquistas has filtered out from Spanish historiography[3] and public discourse[4] into the English academic language.[5] Alternative terms used are "carlistas oficialistas",[6] “carlistas colaboracionistas”,[7] “carlistas unificados”,[8] “carlismo franquista”,[9] “tradicionalistas pro-franquistas”,[10] “pseudotradicionalistas franquistas”,[11] “carlo-falangistas”,[12] “carlo-fascistas”,[13] "tradicionalistas del Movimiento",[14] “tacitistas”[15] or "carloenchufistas",[16] usually highly abusive and disparaging. There is no obvious corresponding but non-partisan term available.

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Carlism at war, 1830s

Carlism, the movement born in the 1830s, during the following 100 years became known for rigid, die-hard, adamant stand – by supporters hailed as virtuous principled consistency and by opponents ridiculed as backwater fanaticism – rather than for political compromise and give-and-take alliances.[17] The movement has always prided itself in totally independent, unaligned status. At different points in time it absorbed various political groupings, like the so-called apostólicos in the 1830s or the so-called neocatólicos in the 1860s, rather than joined alliances with others.[18] In fact, periodically surfacing temptations to form broad coalitions were usually quashed and resulted in secessions, like in case of the so-called pidalistas in the 1870s or the so-called mellistas in the 1920s.[19] Even mild and provisional attempts to co-ordinate political strategy within the monarchist camp generated enormous internal resistance and were eventually abandoned, like in case of the so-called TYRE in the mid-1930s.[20]

Until the late 19th century the Traditionalists viewed the army as a backbone of godless state, ravaged by liberalism, masonry and secularism[citation needed];[21] this approach started to change in the 1880s. While highly suspicious of other parties and unwilling to engage in political trade-offs, since the late 19th century Carlism was increasingly looking towards the military as to a potential partner on the path towards seizing power. Encouraged by the rise of Boulangism in France, they started to hope for a general who would be prepared to carry out a conservative coup d’état; in such case, they were ready to lend him their support.[22] Throughout the next few decades these speculations focused on a few individuals, like Polavieja, Weyler, Primo de Rivera or Sanjurjo. In most cases these schemes eventually failed,[23] though in the early summer of 1936 the Carlists managed to close a vague and ambiguous deal with general Emilio Mola, chief engineer of the military anti-Republican conspiracy; the agreement sealed their access to the military coup of July 1936.[24]

During first months of the Civil War the Traditionalists viewed the anti-Republican coalition as sort of a Carlist-military alliance; they were increasingly baffled by the rise of general Franco, who in apparent disregard of earlier agreements started to consolidate power and to marginalize all independent political groupings.[25] When in early 1937 he started to make hints about amalgamation of existing organizations into one party, supposed to unite all patriotic individuals, the Carlists were left disoriented. On the one hand, they appreciated the need for political unity as means of winning the war; some of their earlier documents have actually advocated that all parties get dissolved and a common patriotic front be created, most likely themselves assuming the leading role.[26] On the other hand, they feared that in a united amalgam controlled by the military they would either lose political identity or get maneuvered into a minority position.[27] During a series of meetings between February and April 1937 the Carlist executive proved split in two. The faction led by Rodezno advocated compliance and suggested the Traditionalists take part in buildup of an anticipated unified organization; the faction led by Fal suggested non-participation.[28] Eventually the former prevailed and the regent-claimant grudgingly provided his consent to enter unification talks.[29]

Remove ads

Emergence of carlo-franquismo

Summarize

Perspective

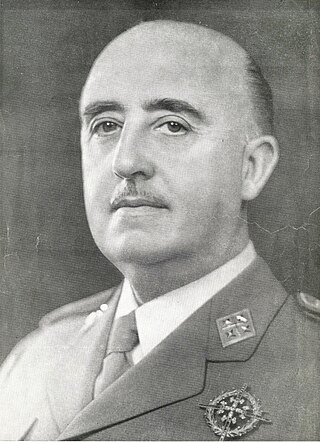

Franco in Carlist beret[30]

In April 1937 it turned out that there would be no negotiations about conditions of merger into the new monopolist party.[31] Franco and Serrano have designed the unification terms themselves; the Carlists were barely consulted, and they learnt about emergence of Falange Española Tradicionalista from the official decree.[32] Their own organization, Comunión Tradicionalista, was declared amalgamated into FET together with Falange Española and all other individuals willing to join. Program of the new party was modeled after original national-syndicalist principles of Falange, with little if any attention paid to traditional Carlist outlook.[33] The 10-member FET executive, nominated by Franco, included five Falangists, four Carlists and one Alfonsist.[34] Where possible, authorities staged public demonstrations of unity: joint parades, marches and rallies. The new state party soon started to seize assets of pre-unification parties, like newspapers, buildings or bank accounts. The Francoist administration made it clear that non-compliance was not a viable option.[35]

Despite official pressure, the Carlist command continued to operate as leadership of independent political grouping. Though executive bodies like Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra ceased to meet, by means of semi-clandestine pre-war territorial structures or informal communication networks the Traditionalists tried to save their property from takeover by FET and to retain own political identity of the movement.[36] Their attitude towards the unificated state party and the emerging Francoist regime was highly ambiguous; falling short of explicit opposition, it amounted to marginal controlled participation. It seemed that the Carlist executive were prepared to put up with unification as a limited, temporary measure, acceptable for duration of the war.[37] Don Javier authorized selected individuals to enter FET command structures but he expulsed from Carlism these who took positions without his consent.[38] In case of major administrative jobs like civil governors or mayors of large cities the Comunión leaders welcomed appointments of their men given the individuals in question kept working for the cause and do not abandon the Traditionalist outlook.[39]

It soon turned out that the process of controlled Carlist participation in Francoist structures was not manageable. As the emerging new system was taking shape, more and more Traditionalist militants were accepting positions in various structures not seeking any formal authorization or informal approval on part of their leaders.[40] Some of them retained close links with Carlist structures, some merely cultivated selected Carlist relations, and some preferred to discontinue their Carlist engagements. In their new party and state roles some actively promoted Traditionalism e.g. by means of propaganda or personal appointments, some strictly stuck to the official "unificated" line, and some turned into zealous new Falangists, advancing national-syndicalism and at times engineering anti-Traditionalist measures.[41] In the late 1930s and early 1940s it was already clear that a significant section of Carlism was actively engaged in development of Francoism.[42] Though internally heterogeneous, this group emerged as a visible component of the Spanish political scene. It was distinct from other currents forming the regime, like pre-war Falangists, Alfonsists or generic conservatives. It was also distinct from independent Carlism, which continued to operate on the verge of legality, beyond the official political framework and at times assuming recalcitrant, if not openly opposing stance versus the regime.[43]

Remove ads

Mechanisms of recruitment

Summarize

Perspective

Josep Carles Clemente lambasted carlo-francoists as traitors pure and simple.[44] In such case they were usually presented as people who betrayed Traditionalism for the sake of their own, personal interest, which either took shape of political power or translated into wealth and material gain.[45] Other scholars agree that numerous individuals have probably joined due to opportunism and careerism; they concluded that active engagement in Francoist structures would improve their personal lot, and that non-participation would harm their position.[46] However, there were also numerous political mechanisms responsible for Carlist access.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s many individuals joined because of bewilderment or disorientation[citation needed]. Some believed that Carlist leadership willingly entered the unification path.[47] Some concluded that with death of Alfonso Carlos and new polarization caused by the Civil War, Carlism was to melt down in a new political amalgam, possibly embodied in the emerging Francoist state.[48] Some viewed the regime as a temporary framework, needed for duration of the war only and to be dismantled afterwards.[49] Some believed that Carlism might maintain its political identity within the Francoist structures, and some thought that it could even dominate the regime and sideline competitive factions.[50]

In the mid-1940s within Carlism emerged a current named Carloctavismo, centred around a new claimant to the throne;[51] it is not agreed whether he was an independent political agent or a figurehead, manipulated by Franco.[52] Carloctavistas placed all their bets on the regime, either with the intention to outsmart the dictator or in genuine hope of a monarchist-Francoist merger; in some regions of Spain they formed a large fraction of Traditionalists and might have even outnumbered the mainstream Javieristas.[53] With unexpected death of the pretender in 1953, the current gradually dried out, though some of its representatives were active until the late 1960s.[54]

In the mid-1950s mainstream Carlism changed its stand versus Francoism; non-participation bordering opposition gave way to cautious engagement and rapprochement with the regime.[55] The movement returned to the earlier controlled access strategy and its members,[56] including top leaders, started to aspire to official posts;[57] the process produced another wave of Carlists landing jobs within state, party and media structures.[58] It lost momentum in the early 1960s, when Traditionalist executive realized that the path would not lead them to power and that Franco was determined to contain the movement in minority positions.

Since the mid-1960s another mechanism of recruitment started to operate. At the time Carlism was increasingly subject to internal power strife between Traditionalists and the progressist faction of Carlos Hugo; the latter were gaining the upper hand. Some of those sidetracked or leaving willingly were determined to restrain the carlo-huguistas by all means possible, including an alliance with the regime.[59] Also Franco, the master of balancing game, started to lure disappointed Traditionalists into his camp. The result was a group of Carlists, including most recognized individuals, assuming prestigious posts in official structures.[60] The process continued until the early 1970s; some of these late carlo-francoists soon withdrew into the back row,[61] but some assumed key roles and in the mid-1970s they were among leaders of the so-called hardline Francoist bunker.[62][citation needed]

Remove ads

Modes of engagement

Summarize

Perspective

During primer franquismo many Carlists who joined the regime structures remained totally committed to the Traditionalist cause[citation needed]; they did their best to promote Carlism at the expense of Falangist syndicalism.[63] These attempts have generated resistance, typically either on part of the military or the Falangists; castigated as attempts to build local “Carlist fiefdoms”,[64] they invariably[citation needed] led to counter-action and individuals in question being usually[65] either ousted[66] or marginalized;[67] some resigned on their own.[68] There were two exceptions, though. In Navarre the Traditionalists managed to mount successful opposition to falangisation of the province and achieved sort of a balance of power.[69] Except the late 1940s, also the Ministry of Justice remained dominated by the Carlists, who controlled not only mid-level posts but also institutions dependent on the ministry.[70] Some 30 years later a distinct group of committed Carlists competed for seats in the Cortes; their objective was to dismantle the system from within.[71][citation needed]

Another attitude adopted was clinging to Carlist outlook as long as it did not stand in the way of political career and did not generate major controversy[citation needed]. Individuals in question could have attended Traditionalism-flavored feasts (though not independent Carlist political rallies), sponsored or otherwise supported Traditionalism-flavored periodicals, appointed moderate, non-belligerent Carlists to jobs which remained under their control, openly admitted in the press their Traditionalist background and mindset, or at times even visibly saturated official ceremonies with Carlist essence,[72] though all this always within limits permitted by sense of loyalty to Franco and the regime.[73] With sufficient degree of skill and craft, such tactics could have worked, either in the military,[74] or at the level of provincial ayuntamiento[75] or at presidency of the Cortes.[76][citation needed]

There were individuals who authentically strove to achieve synergy between Traditionalism and what they understood to be a patriotic amalgam.[77] They clung to their Carlism not as to an independent political standing, but approached it as a valid component of the fused ideology, especially after the system shook off major vestiges of Fascism and started to pose as “monarquía tradicional católica, social y representativa”. Some did not engage in political structures of Francoism, but they rose to top figures of public life, e.g. in science,[78] or self-government.[79] Others, having been rather few genuine “unificated” Francoists, emerged as recognizable political personalities, e.g. holding numerous posts of civil governor in the 1940s;[80] some joined the intransigent Francoist hardline core and mounted a last-ditch attempt to save the falling system in the mid-1970s.[81]

A large and most representative group of Carlists who joined the regime structures have abandoned their Traditionalist militancy almost entirely or indeed entirely. When holding official posts they demonstrated no particular sympathy for the movement and terminated any links relating them to the organization, its initiatives or individuals, perhaps except strictly private contacts.[82] Single individuals grew to hierarchs of the system and became public faces of Francoism, but at this role they have not revealed any preference for Traditionalism.[83] Some former militants who discontinued their party engagements went even further and have actively engaged in anti-Carlist measures; they engineered or executed initiatives aimed against either independent Traditionalism or against carlo-franquistas who cultivated their Traditionalist heritage.[84]

Remove ads

Cohesion and conflict

Summarize

Perspective

The Carlists who joined Francoist structures have never formed a homogeneous group, either in functional or structural terms. Except that they were all coming from the same political background there was hardly any particular behavioral feature that would have rendered them a cohesive faction. They were not united by uniform motivations, common objectives, or similar modus operandi. Though many of them attempted to preserve or at times even to promote Traditionalist ingredients, there were also many who have abandoned even lukewarm or watered-down Traditionalist sentiments. The carlo-franquistas neither built any structural network and there has never been even a shadow of their organization. The closest thing were structures of the Ministry of Justice, where many former Carlists found employment;[85] however, the ministry has never become anything even vaguely resembling their operational headquarters or political backbone.

During almost 40 years of Carlist presence in Francoist structures there were periods of competitive sub-factions operating within the group[citation needed]. In most cases[citation needed], divisions were developed along dynastical lines, though they also translated to different visions of the regime itself. An early example comes from the late 1940s. One section worked for the cause of the Alfonsist claimant Don Juan, considered ready to adopt Traditionalist principles; this bid was associated with the concept of a somewhat liberalized regime.[86] They competed for influence against the Carloctavistas, determined to support their own claimant, Don Carlos Pio, and aligned with the hardline Francoist idea of state and society; the group found cautious supporters among top-positioned Carlists.[87] Another example of competition is dated at the early 1960s. A wave of militants from the independent Carlist Javierista branch landed posts in FET Consejo Nacional and in the Cortes; their objective was to promote Don Carlos Hugo as a prospective Franco-appointed king. At the time a group of influential carlo-franquistas were already engaged in so-called “operación salmón”, a long campaign in support of Don Juan Carlos as the future king of Spain.[88] An example of conflict non-related to dynastic issues was the one centred on Law on Religious Liberty of the late 1960s; one faction promoted the draft and another one tried to block the law.[89]

Within carlo-francoism certain individuals emerged as most prestigious politicians or perhaps even as informal leaders, though there has never been one unchallenged champion of the cause. The only person who built his own clientage was conde Rodezno[citation needed], minister of justice in 1938-1939 and member of the Cortes later; since the late 1930s until the early 1950s he was leading a group named Rodeznistas. He was succeeded at ministerial post by Esteban Bilbao, Antonio Iturmendi and Antonio Oriol, but none of them enjoyed comparable standing, even though Bilbao and Iturmendi grew also to speakers of the Cortes and members of Consejo del Reino and Consejo de Regencia, while Oriol and Joaquín Bau entered Consejo del Reino and Consejo de Estado. The only other individuals which stood out among the carlo-franquistas were Jesus Cora y Lira (early 1950s) and José Luis Zamanillo (early 1970s)[citation needed], the former as champion of Carloctavismo and the latter among key personalities of the búnker. However, personalist terms like “Iturmendistas”[90] or “Zamanillistas”[91] were used only exceptionally.

Remove ads

Statistical approximation

Summarize

Perspective

The weight of Francoism within Carlism remains unclear. None of the sources consulted estimates what proportion of Carlists actively engaged in buildup of Francoist structures and how large was the carlo-francoist faction within Carlism in general.[93] General historiographic accounts present contradictory views. On one hand, numerous high-level overviews of history of Spain or the Spanish Civil War tend to blanket statements which suggest that Carlism was absorbed in FET and ceased to exist as autonomous political current.[94] Also some focused works suggest that the movement was fully integrated in the emergent Francoist system.[95] On the other hand, there are historians who present Carlism as a systematic opposition to the regime and play down cases of collaboration as entirely marginal.[96] Prosopographic reviews reveal that many pre-war Traditionalist leaders or otherwise distinguished personalities at one point or another chose to enter Francoist structures. Among members of the 1932 Carlist executive who survived the war at least 43% actively supported the emerging Francoism.[97] Some 68% of surviving Carlist deputies to the Cortes of the Republican era actively engaged in the regime;[98] for Traditionalist candidates to the Republican Cortes the figure was 44%.[99] Among members of Consejo de Cultura, a board of Carlist pundits set up in the mid-1930s, some 38% of these surviving assumed various posts within Francoism.[100] Some 67% of members of Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra, the Traditionalist wartime executive created in August 1936, were later engaged in Francoist structures.[101] Whether the above figures, representative for high command layer, are applicable to mid-level leadership or to rank-and-file, is not clear.[102]

The weight of Carlism within the Francoist regime has already been subject to numerous quantitative estimates.[104] One study claims that individuals clearly identified with Traditionalism formed 2,5% of all government ministers,[105] another author opts for 4,5%.[106] The duration of particular tenures factored in, clear-cut Traditionalists occupied 4,2% of ministerial posts available during 36 years in question;[107] with those vaguely associated the figure is 9,7%.[108] According to one scholar the Carlists formed some 3,1% among members of the quasi-parliament, Cortes Españolas;[109] the 4% threshold was exceeded during only 2 terms, in 1943-1949 and 1958–1961.[110] One scholar claims that within the contingent of civil governors, during primer franquismo some 14,5% officials were related to Traditionalism;[111] another scholar calculated that there has never been more than 3 Carlist governors during any specific period.[112] Until the mid-1940s among vaguely specified personal político some 6,6% were Traditionalists; there is no similar statistics available for the remaining 30 years.[113] In the very initial period Carlists made up some 22-24% of the party executive Consejo Nacional,[114] but since the early 1940s their share of seats remained in the range of 5-10%;[115] it climaxed to 13% in 1958.[116] Initially they held 29% of provincial FET jefaturas[117] and commanded 18% of specialized FET branches;[118] later this share dropped dramatically. Locally the percentage of Carlists holding posts of power could have differed widely; studies for traditional Carlist strongholds like Navarre or Vascongadas indicate Traditionalist share of power in ranges between 30 and 50%,[119] while in case of regions with noticeable though not dominant Carlist presence the figure drops to 2-3%.[120] In the late 1940s the Carlists formed some 3,3% of all concejales in local ayuntamientos in Spain.[121] Regardless of detailed figures, there seems to be a general agreement that the Carlists formed a minor fraction among holders of high jobs within the regime.[122]

Remove ads

Personal trajectories

Summarize

Perspective

It is close to impossible to sketch a typical path of a Carlist engaged in Francoism. Personal careers differed widely, from time of access to level of enthusiasm to political success or failure. Moreover, numerous carlo-francoists did not maintain a consistent stand during almost 40 years of the Franco regime; many demonstrated a vacillating approach, marked by varying modes of engagement or even by erratic twists and turns of their careers.[citation needed]

A significant group of recognized personalities who landed top jobs in the late 1930s in few years were already no longer associated with the official policy. Some got increasingly disappointed with the emerging system and resigned,[123] up to total withdrawal into privacy;[124] some were sidetracked to marginal roles by political opponents;[125] some were totally ousted[126] and persecuted, up to the point of serving jail sentences.[127] A large group scaled down their engagement in the system; having earlier been chief promoters of unification, they later preferred to remain at arms-length and pursued their own objectives.[128] There were cases of grand returns, marked first by engagement, then by marginalization, and then by re-engagement,[129] at times including assumption of top state jobs.[130] Some individuals re-engaged to dismantle the system from within;[131] some re-engaged to abandon the officialdom again and to work to other political ends.[132][citation needed]

There were examples of political transformation in the opposite direction, when opponents to Francoism later joined its official structures. Some individuals outwardly rejected high ministerial jobs in the 1940s but were aspiring to them in the 1960s; when eventually assuming prestigious posts they could have adhered to Francoist orthodoxy or they could have advanced own political schemes.[133] In few cases the U-turn performed was dramatic, as most zealous adversaries of the system turned into its most zealous advocates. There were individuals who resigned jobs in Carlism as a measure of disagreement with unification and were jailed or exiled, but some 20 years later they neared the regime; they not only landed prestigious jobs, but also emerged as most vociferous advocates of Francoism during its terminal years, speaking out against the commencing transición.[134][citation needed]

Last but not least, a large fraction of carlo-francoists maintained a fairly constant stand. Very often it boiled down to amalgamation into Francoist structures.[135] With focus on ongoing administrative work, their political activities were reduced to hardly visible minimum;[136] this was the case especially of mid-level officials[137] and military men.[138] Most of them got consumed by routine and advancing in age, ended up as colorless bureaucrats.[139] Some recorded periods of more intense militancy interchanging with dormant decades spent on day-to-day routine tasks.[140] Some for most of the time remained somewhat lukewarm participants; undecided whether to engage or to withdraw, they refused major jobs and for years performed second-row roles.[141] Some became public faces of the regime and started to demonstrate dissent no earlier than on retirement.[142] Few, following decades at minor positions, grew to more important roles, e.g. as mayors of provincial capitals[143] or assuming high jobs in central administration.[144] Finally, some having entered the regime identified with it totally and throughout the rest of their career remained militant Francoists, engaged in eradicating perceived opposition or groupings deemed not sufficiently loyal to caudillo.[145][citation needed]

Remove ads

Impact

Summarize

Perspective

There are very few studies which try to gauge the actual political impact of the carlo-franquistas. In most cases they are merely listed among so-called “families” which made up the official political amalgam, along the Falangists, the Alfonsists, the military, the technocrats and the Church.[146] Within such perspective all these groupings are presented as constantly competing for power and trying to outmaneuver the others,[147] while Franco mastered the practice of balancing them. The Carlist component of the regime is usually presented among the least influential ones; only in the period between the mid-1940s and the mid-1950s it enjoyed somewhat less marginal position. Though as part of the official amalgam the Traditionalists are deemed co-responsible for final Nationalist triumph in the Civil War, repressive policy of early Francoism or some liberalization of the regime later on, no scholar claims they can be credited for shaping the system.[148]

Except preservation of semi-separate establishments in Álava and Navarre,[149] the list of carlo-francoist political accomplishments is mostly about thwarting radical Falangist designs. In 1940 they mounted a successful opposition to totalitarian draft of Ley de Organización del Estado.[150] In aftermath of the 1942 Begoña crisis the Carlist outrage contributed to de-emphasizing of Fascist threads.[151] Ley de Sucesión en la Jefatura del Estado of 1947, co-drafted by Carlists in the ministry of justice, was by many viewed as designed with the Carloctavista claimant in mind.[152] The draft of Leyes Fundamentales, promoted in the mid-1950s, was dubbed resemblant of Soviet-style regime and eventually blocked by a coalition of Carlists and other groups.[153] The 1958-adopted Ley de Principios del Movimiento Nacional defined the state party using a Carlist notion of a “comunión” and declared Spain “monarquía tradicional, católica, social y representativa”, which vaguely resembled Traditionalist outline; however, practical effects were none. In the early 1960s, the Juan-Carlos-minded faction of carlo-francoists contributed to thwarting regalist ambitions of the Javierista hopeful Don Carlos Hugo;[154] in 1969 they saw Don Juan Carlos declared the future Spanish king and in the early 1970s they assisted in ensuring his ascendance against the hardline Francoist “regentialist” faction.[155]

The list of carlo-francoist failures starts with marginalization in the state structures. They occupied no more than 5-10% of top posts, were unsuccessful at shaping the regime,[156] and at best were used by Franco as a counter-weight when he needed to keep other political groupings in check. During almost 40 years they failed to get any of their preferred claimants crowned, be it Don Juan, Don Carlos Pio, Don Javier or Don Carlos Hugo; the crowning of Don Juan Carlos came about already after the death of Franco and his rise to power was the process that the carlo-franquistas did not control. Except the role of culture and religion, which until the mid-1950s resembled the Traditionalist model,[157] other spheres of public life in Franco's Spain did not conform to Carlist prescriptions.[158] In broad terms, the carlo-francoists failed to implement Traditionalist blueprint upon Spain of the mid-20th century. Their defeat was marked by adoption of Ley de Libertad Religiosa in 1967;[159] it contravened most fundamental Carlist principles and was followed by further transformation, leading towards buildup of consumer, democratic, secular society. Marginalization of post-Francoist Carlists was amply demonstrated during the transición, when their electoral attempts ended up in utter failure.[160]

Remove ads

Appendix. 100 Carlists at top Francoist positions

Summarize

Perspective

Individuals loosely related to Carlism:

Remove ads

See also

Footnotes

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads